Section I – NY66NW

Contents

Section I – NY66NW – this is a section of Hadrian’s Wall showing the LiDAR, Google Earth and 1800 Maps of the Area covered by Historic England

Historic England Sections:

Hadrian’s Wall – between Stanegate Roman road and the boundary west of Coombe Crag in wall miles 46,47, 48, 49, 50 and 51

List UID: 1015923, 1010993, 1010994, 1010995, 1018242

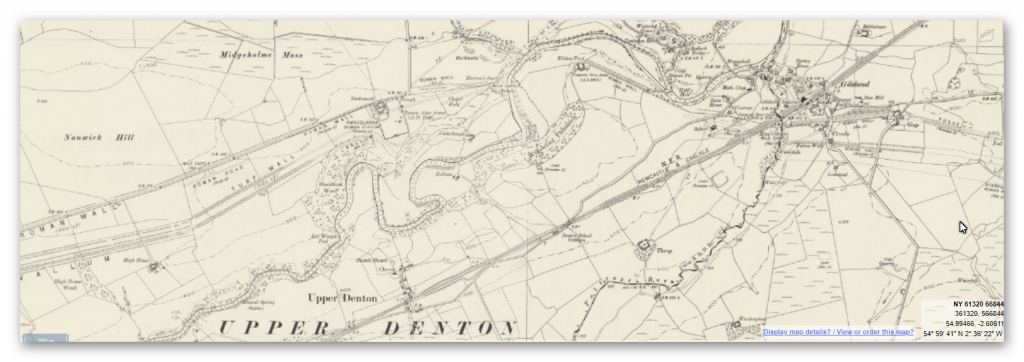

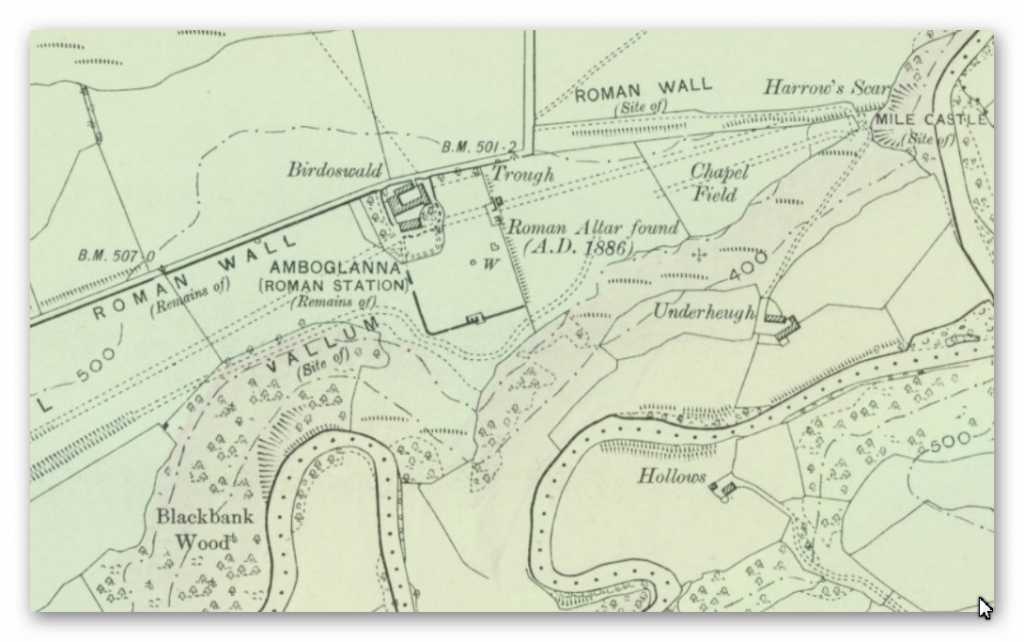

Old OS Map

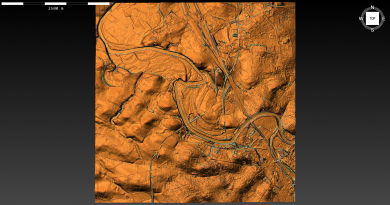

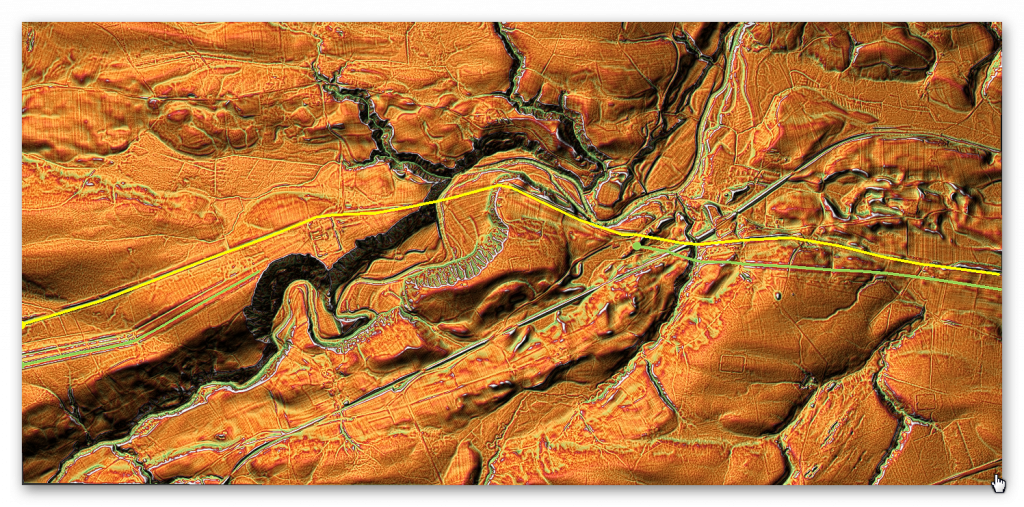

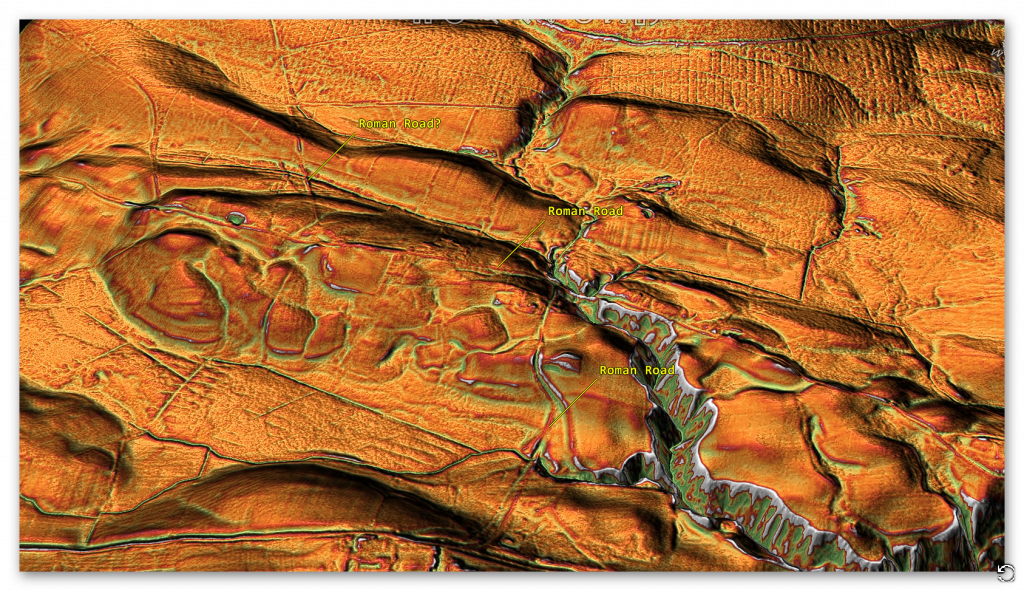

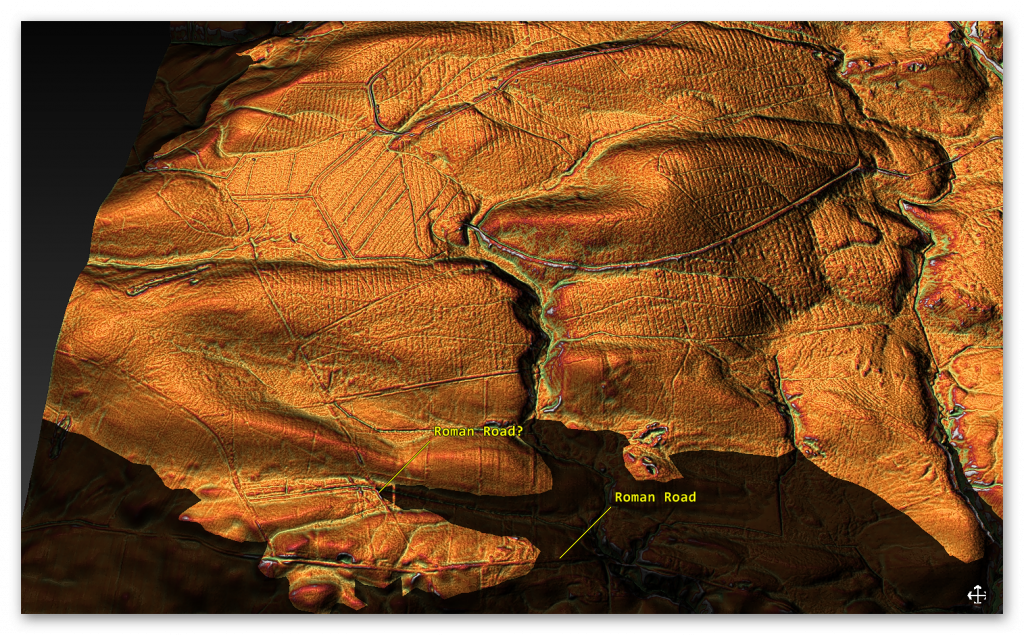

LiDAR Map

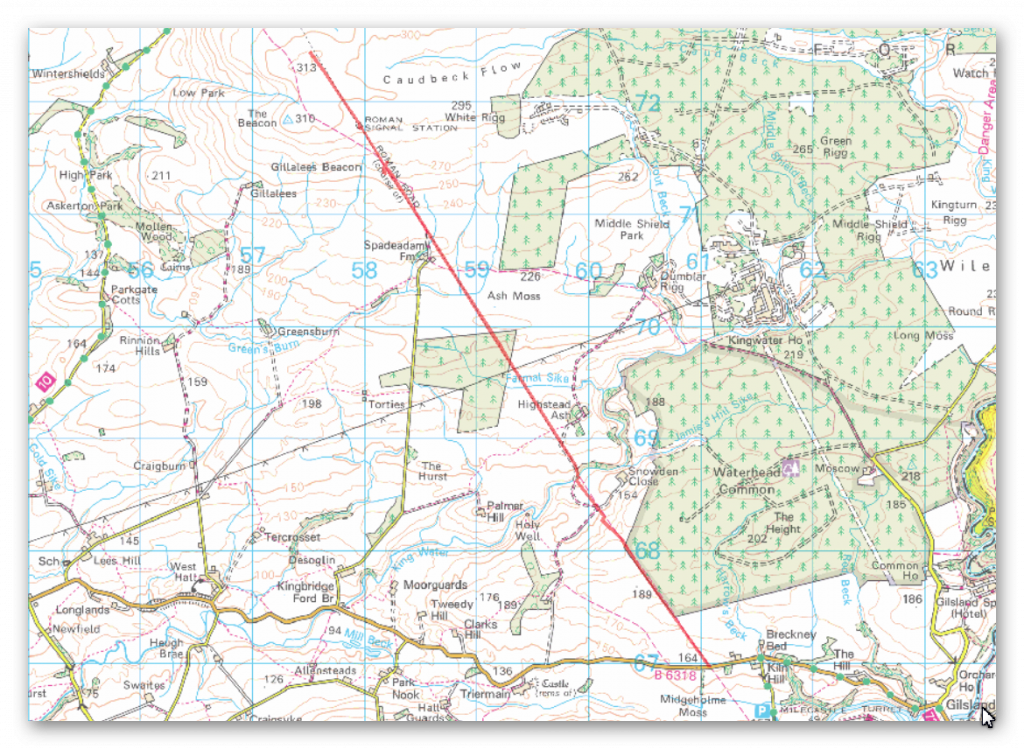

Google Earth Map

Historic England Scheduled Monuments within Section I

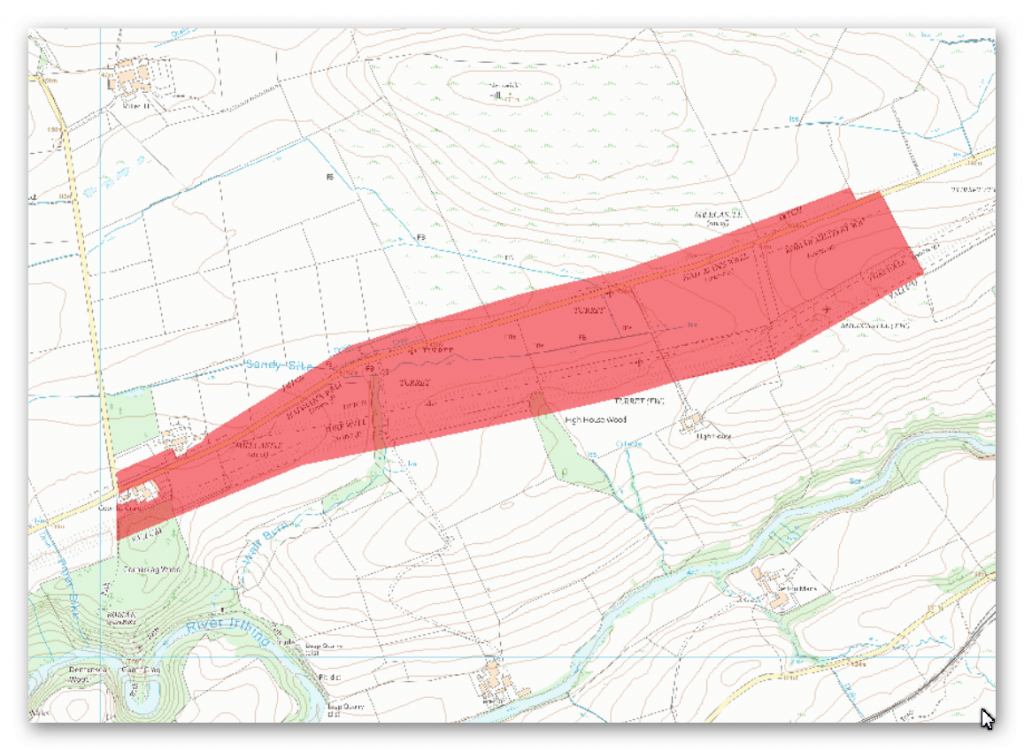

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between the field boundaries east of milecastle 50 and the boundary west of Coombe Crag in wall miles 50 and 51

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010995

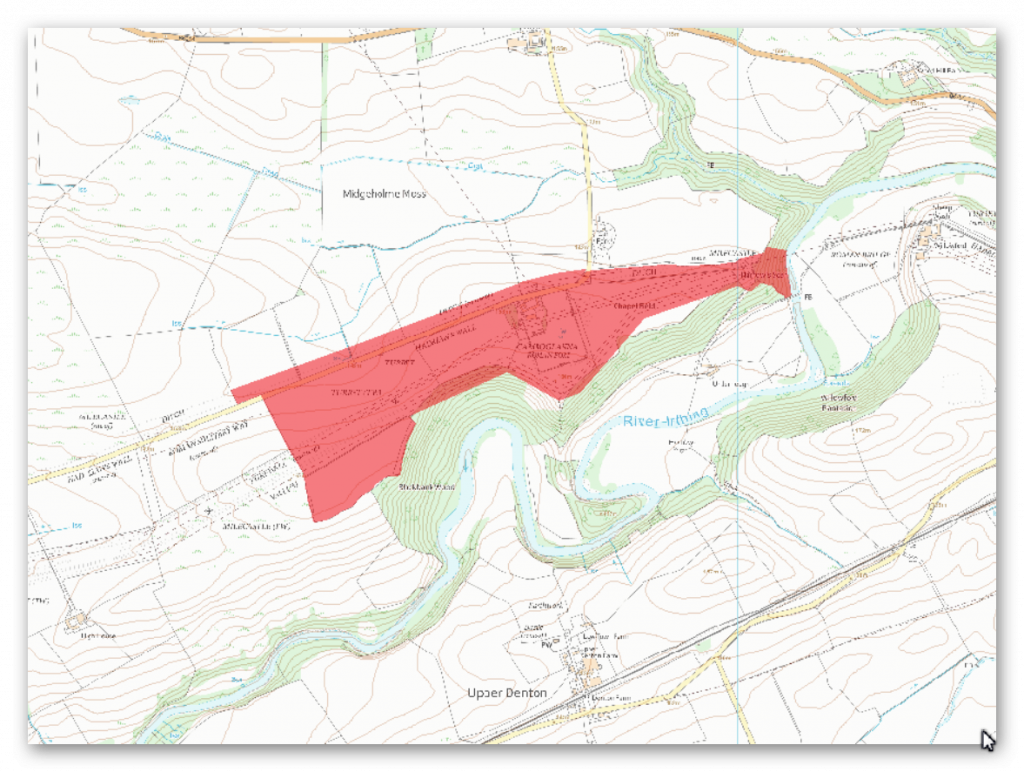

Name: Birdoswald Roman fort and the section of Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between the River Irthing and the field boundaries east of milecastle 50

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010994

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum and their associated features between Poltross Burn and the River Irthing in wall mile 48

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1015923

Name: Hadrian’s Wall, vallum, section of the Stanegate Roman road and a Roman temporary camp between the B6318 road and Poltross Burn in wall miles 46 and 47

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010993

The monument includes the section of Turf and Stone Walls and vallum between the field boundaries east of milecastle 50 in the east and the field boundary west of Coombe Crag in the west.

The Turf Wall survives as a buried feature below grassland throughout this section. At the west end of this section its course is defined by a low broad mound, with a maximum height of 0.4m. Elsewhere there are no visible remains above ground. The Turf Wall ditch survives as an earthwork visible on the ground. It averages between 1.1m and 2m deep throughout this section. The ditch upcast mound, usually referred to as the glacis, also survives as a low mound to the north of the ditch. It measures up to 1.6m high in places. Milecastle 50 on the Turf Wall is situated on a gentle west facing slope with the steep gorge of the Irthing to the south. The south part of the milecastle is marked out in the turf, but otherwise there are no remains visible on the ground. Its remains however survive as buried features below the turf cover.

Excavations were carried out by Simpson in 1934 which identified a causeway across the Turf Wall ditch to the north. Turret 50a on the Turf Wall survives as a buried feature below the turf cover with no remains visible above ground. It is situated about 180m north west of High House. It was located in 1934 by Simpson. Turret 50b on the Turf Wall also survives as a buried feature below the turf cover with no remains visible above ground. It is situated about 120m east of the Wall Burn. It was located and partly excavated by Simpson and Richmond in 1928. The Stone Wall in this section survives as a buried feature below the ground immediately south of the modern road at the east end of this section and below the road surface itself throughout the rest of the section. The ditch survives well as an earthwork visible on the ground immediately north of the modern road. It is well preserved measuring between 1.7m and 2.5m deep. The ditch upcast mound, or glacis, is visible to the north of the ditch. It survives as a low sinuous mound averaging 1m in height. Milecastle 50 on the Stone Wall is situated about 170m north of milecastle 50 on the earlier Turf Wall. It survives as a ploughed down turf covered platform bounded on the east and the west sides by a spread scarp with a maximum height of 0.2m. Two distinct rises in the roadside wall define the position of the east and west walls. Excavations by Simpson took place in 1911. It measured 23.4m internally north to south by 18.5m across.

Its walls were of narrow type measuring 2.3m across. The original internal buildings appear to have been timber structures. These were later replaced by stone buildings. Fragments of three legionary inscriptions were also found; two referring to the sixth legion and one to the second legion. Milecastle 51 is situated 150m east of Wall Bowers and survives as a series of turf covered remains mostly on the south side of the modern road. The east and west walls survive as animal trampled robber trenches, 3m wide and with a maximum depth of 0.15m. The north wall is buried below the modern road. An outer ditch is discernible on the east side, curving around to the south side before fading. It survives up to 4.5m wide and 0.3m deep. It is at this milecastle that the Turf Wall and Stone Wall converge before continuing west on the same alignment. Excavations of the milecastle by Simpson in 1927 revealed the gateway and two stone barracks, one either side of the central space. Turret 50a on the Stone Wall is situated about 50m west of the track to High House. There are no remains visible above ground.

The north half survives below the road surface whereas the south half is recognisable as an amorphous swelling at the edge of the adjoining field. It was partly excavated by Simpson in 1911 who recovered two inscriptions to the sixth legion, who it seems were responsible for rebuilding the first five miles of the Turf Wall in stone. Turret 50b on the Stone Wall is situated to the east of Appletree. It survives as a buried feature partly below the modern road and partly below the adjoining field to the south. The turret was located and partly excavated by Simpson in 1911. It was shown to have remained in use after the second century, and fragments of window glass imply that the turret’s windows were glazed.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known throughout this section. It survives as a vague but detectable intermittent terrace or mound visible on the ground. It is best preserved to the west of Wall Burn where it survives as a linear causeway, 0.4m high.

The Vallum survives well as an upstanding earthwork in all but the easternmost part of this section where it survives as a shallow ditch and ploughed down earthwork. Elsewhere the ditch averages 1.5m deep, the north mound 2m high and the south mound 0.9m high. West of Turf Wall milecastle 50 the north mound reappears again abutting the west wall of the milecastle.

Excavations at the milecastle in 1936 have shown that there is no north mound between milecastle 50 and Birdoswald fort, but rather a south mound twice the usual size. Outside Turf Wall milecastle 50 the south mound and ditch bend around the milecastle with a paved access road opposite the south gateway and a paved track along the south berm.

The monument includes the Roman fort at Birdoswald and the section of Hadrian’s Wall and vallum and their associated features between the River Irthing in the east and the field boundaries east of milecastle 50 in the west.

In the original construction of Hadrian’s Wall, the Wall west of the River Irthing was built as a turf rampart, probably due to a lack of building stone in the immediate vicinity. East of the Irthing the Wall was built from stone. However, by the end of the second century AD, the Turf Wall section was rebuilt in stone.

The Turf Wall ran from the milecastle at Harrow’s Scar to the south side of the east gate of Birdoswald fort, continuing on the west side from the west gate. However, excavations in 1894 by the Cumberland Excavation Committee and in 1945 by Simpson and Richmond showed that the Turf Wall and its ditch were overlain by the fort. Its course has been confirmed by recent geophysical survey. The remains of the Wall survive as buried features with the only feature visible on the ground being the Turf Wall ditch west of the fort where it appears as a broad shallow depression occupied by a buried land drain.

The Stone Wall survives very well in this section, being visible as an upstanding stone monument for most of this length. It averages 2.2m wide on a broad foundation 3m wide and averages over 1m high. There is an 874m stretch of the Wall which is consolidated and in the care of the Secretary of State in this section.

In the section east of Birdoswald fort there are eight Roman inscribed stones in the south face of the Wall. The Wall where it coincided with the north wall of the fort has been largely levelled by the farm complex. Buried remains will survive below the farm area and road. At the west end of this section the remains of the Wall are buried below ground to the south of the modern road. The wall ditch is visible in this section immediately to the north of the modern road which occupies the berm between the Wall and ditch. Here it averages 2m in depth. Towards the fort the ditch fades out due to silting; east of the fort the ditch is silted and marshy.

Remains of the ditch upcast mound, usually referred to as the glacis, survive to the west of the fort as a low amorphous mound to the north of the wall ditch. Milecastle 49 is situated on the west side of the Irthing gorge on the cliff known as Harrow’s Scar. It survives as an upstanding stone feature. It is consolidated and in the care of the Secretary of State. It measures 23m north to south by 20m east to west. Excavations by Richmond took place in 1953 which revealed a gateway and the remains of the earlier phase turf milecastle below it which measured about 16.6m north to south by 15.4m east to west.

The construction of a cottage, which probably dates to the 18th century, has destroyed much of the internal remains. Turret 49a was situated on the line of the Turf Wall before Birdoswald fort was built, although it was itself made of stone, as were all the turrets. It was located by Simpson and Richmond during excavation in 1945. It was situated in the centre of Birdoswald fort below the Commandant’s House. Its remains consisted of foundations only which survive buried below the fort remains. Turret 49b was situated on the line of the Turf Wall 350m west of the west gate of the fort at Birdoswald. It was located by Simpson, Richmond and St. Joseph during excavation in 1934, and was constructed in stone as were all the turrets. The excavators examined only the side walls in order to identify the position of the turret. The walls had been laid in a construction trench, and only the foundations remained. It is likely that the turret was demolished when the replacement Stone Wall was built to the north, and the stone from the Turf Wall turret used in its construction. The turret survives as a buried feature below the turf cover with no remains visible above ground. Turret 49b, built for the Stone Wall, also survives as an upstanding stone feature and its walls have also been consolidated; it is in the care of the Secretary of State.

Excavations in 1911 by Simpson showed there to be two early floor levels as well as late pottery demonstrating that the turret had continued in use, unlike many other turrets. The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known throughout this section. West of the fort it survives as an intermittent low linear mound, 0.1m in maximum height. East of the fort a geophysical survey in 1986 by Walker confirmed the existence of the Military Way below the turf cover.

The vallum survives as a buried feature for most of its course in this section. The only remains visible on the ground are to the south and west of turret 49b where the ditch is up to 2m deep, enhanced by a mole drain along its base. The ditch is also discernible as a depression, 0.4m deep, at the edge of the Irthing gorge.

Excavation by Richmond from 1928 onwards showed that the vallum skirted the fort to the south. Richmond discovered a causeway across the vallum ditch which had vertical sides faced with ashlar and gaps showing where heavy masonry supporting an arched gateway over its centre had been before the structure was dismantled. The vallum seems to have been levelled here at the end of the Hadrianic period and wooden structures erected over its course.

The fort at Birdoswald, known to the Romans as Banna, is situated on the gentle north facing slope of a ridge with a steep scarp to the south. It was located here to guard the bridging point of the Irthing 500m to the east. The walls of the fort are in the care of the Secretary of State. The fort measures 178.5m north to south by 123m east to west, enclosing an area of 2.2ha. It survives as a well preserved fort with walls and gateways standing as exposed features. Farm buildings occupy the north west corner of the fort and the farm yards and the modern road have levelled the north curtain of the fort, which was also the main frontier Wall at this point. There has been a complex history of archaeological work on this site from the early 19th century through until the late 1980s. Buildings identified in the interior include the Commandant’s House excavated in 1945 by Simpson and Richmond, the Commandant’s Bath House excavated in 1850 by Potter, barrack blocks excavated by Richmond in 1928 and granaries, part of the west curtain and gate, together with the triple defence ditches by Wilmott in the late 1980s.

The stone revetted causeway across the ditch outside the west gateway is exposed as an upstanding feature. A unique feature of this fort is the remains of an ashlar structure made of very finely dressed stone on a chamfered plinth abutted by the west wall of the fort, adjacent to the west gate. A large Roman basilica was constructed in the north sector of the fort and was interpreted by Wilmott as a parade or drill hall. Wilmott also discovered an early medieval hall and associated structures constructed inside the fort over the earlier Roman remains, demonstrating continued use of the site in the post-Roman period. The area excavated by Wilmott to the south of the house has been consolidated by English Heritage.

To the south of the fort Richmond located and excavated a pair of parallel ditches which contained Housesteads Ware pottery and leather from a tented camp which predates the fort which was, truncated by the ditch of the vallum.

The excavations in 1930 revealed a building 20ft square with three walls standing 13 courses high, identical in plan to a Turf Wall turret or a signal tower. The depth to which it was buried suggests that it may have been buried within the north mound of the vallum. The fort was originally occupied by the first cohort of Dacians, 1000 strong, and probably early in the third century by the part- mounted first cohort of Thracians. Finds from the fort have included small hoards of denarii as well as altars, statuary and inscriptions. The conversion from the Turf Wall to the Stone Wall in this section involved a new line for the Stone Wall, which was brought up to the north angles of the fort. This created a larger space around the fort to the east and west. This space to the east of the fort may have contained the parade ground for the fort garrison. The parade ground at Birdoswald is attested by an impressive group of official parade ground dedications including over 20 to `Jupiter Best and Greatest’, however its exact position on the ground has not yet been confirmed. In 1859 a delivery tank from an aqueduct was discovered near the centre of the fort together with an underground channel which was still delivering water from a point 277m west of the fort. A civil settlement outside the fort, usually known as a vicus, appears to have been located on the east side of the fort. Trenching in 1898 by Haverfield and in 1930 by Richmond to the east of the east gate of the fort showed evidence of some structures. Remains of buried features are visible on the ground as a series of scarps and stony banks up to 1m high.

The concentration of stone in this area also implies the existence of buildings here. A number of tombstones have been found reused in the fort testifying to an associated cemetery near the fort. The main cemetery may have been located to the west of the fort as the vicus was positioned on the east side and to the south is the steep scarp down to the Irthing. A number of Roman cremations in cinerary urns were discovered during deep ploughing in 1959 in New Field, north of Blackbank Wood. A childs’ sarcophagus was also found but reburied. Furthermore a tombstone was found in this area to the west of the fort in 1961. All field boundaries, English Heritage fixtures and fittings, road and track surfaces and the farmhouse and farm buildings at Birdoswald (elements of which are Listed Grade II) are excluded from the scheduling, but the ground beneath them is included.

Investigation

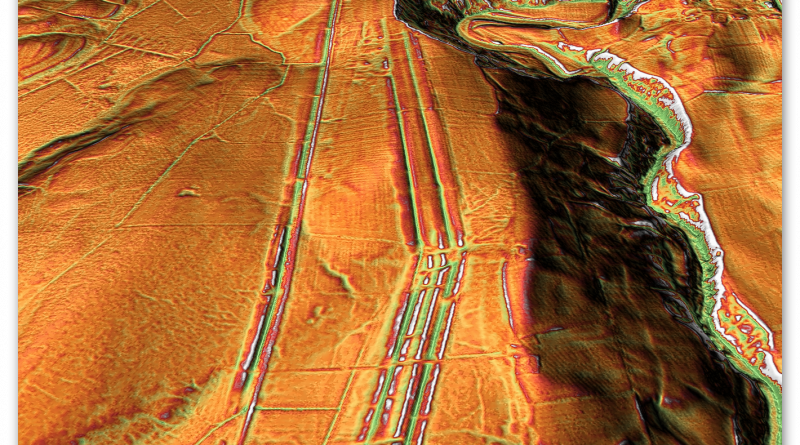

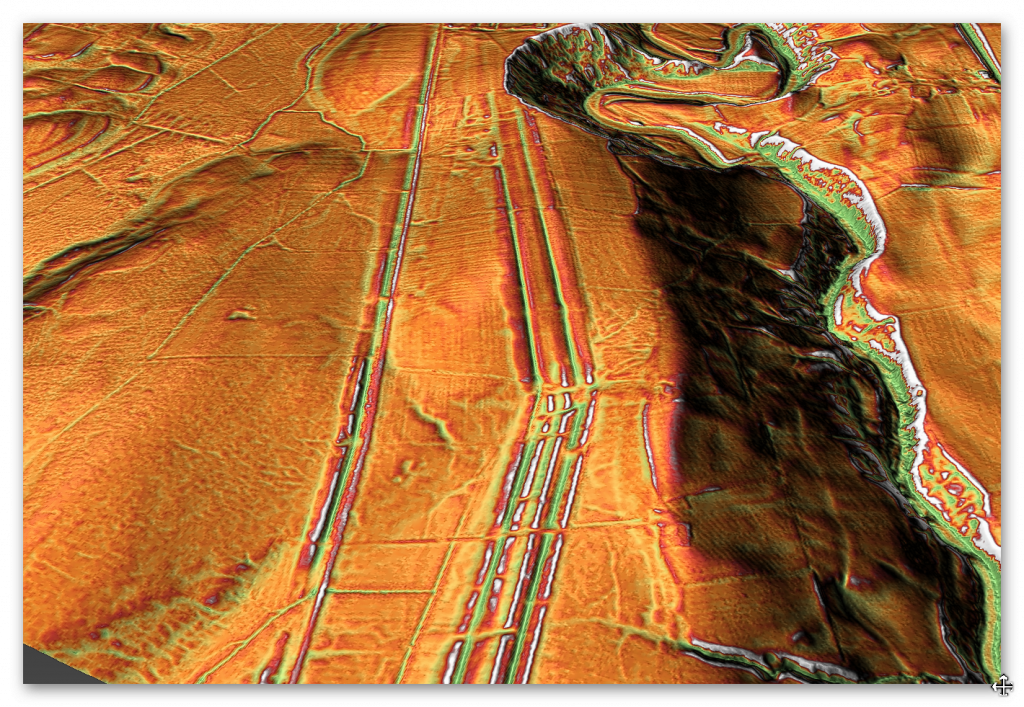

The first problem with the Vallum is the massive change in its construction in the East of this section linked to a 30 degree change of direction for no apparent reason.

The Vallum in this section has the ‘old wall’ and Vallum in close proximity. The Wall and Vallum banks are quite pronounced until they reach this 30 degree turn were they become very flat and the centre strip seems to become very connected like one sing bank rather than the original two banks.

This strange anomaly may be due to either the two sections being built at a separate time period or the section was used for something different to it original design or even something simpler as two work sections poorly connecting after a course correction?

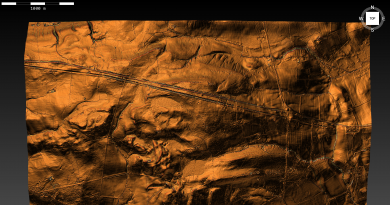

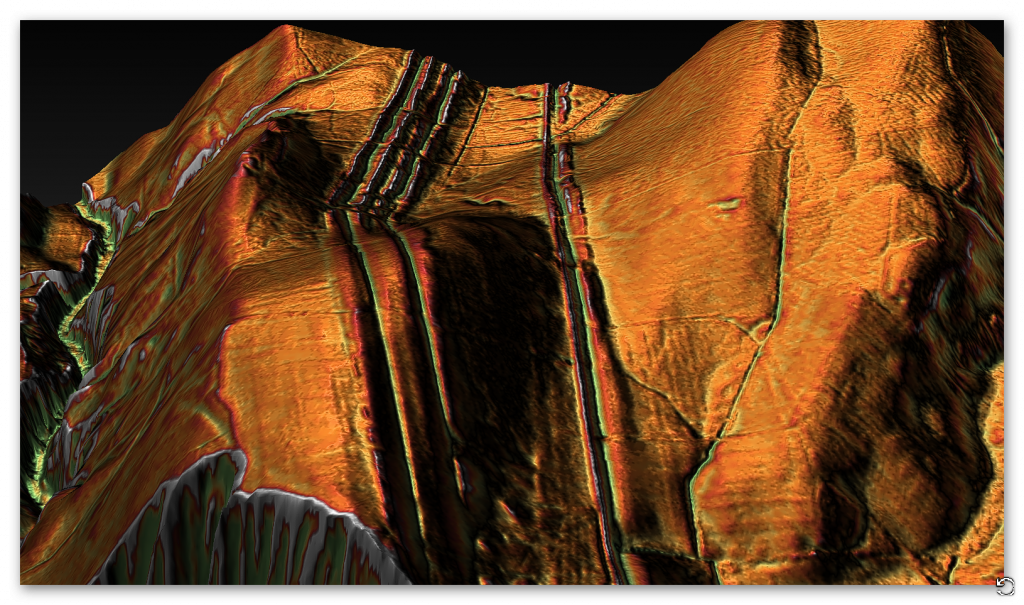

If we exaggerate the landscape by a factor of five using the AI engine within LiDAR maps we can see the extent of the difference between the two sections. We can also see that the east side of the Vallum may have stopped in the small paleochannel and that the where the change occurred – maybe to have another section added at a later date to link, with just the ditch (not the bank) being a main reason for the connection. This would question if the Wall section had been moved (see section H for details) or the Vallum was always meant to have a double ditch in this section?

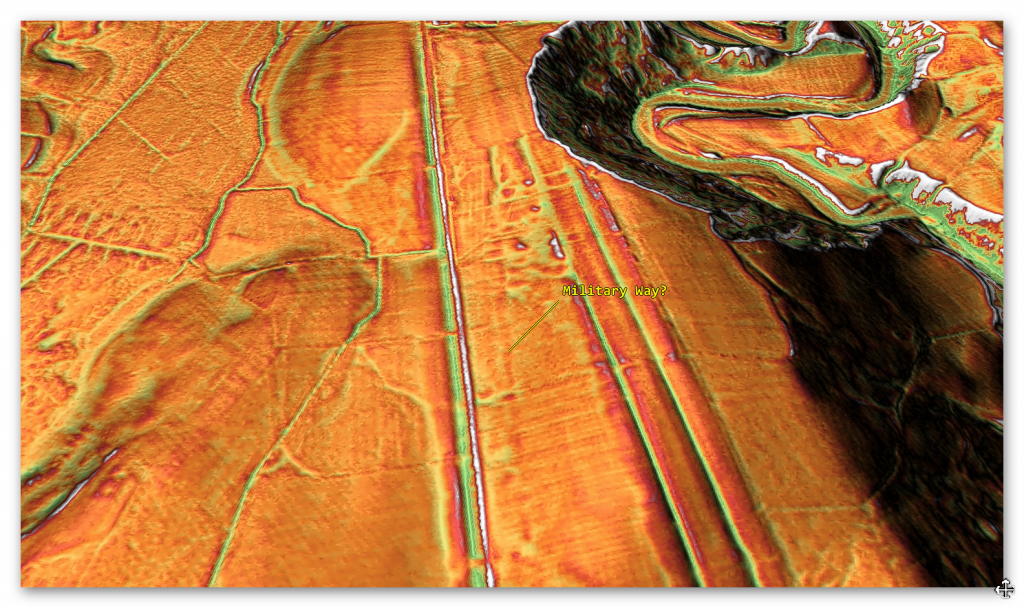

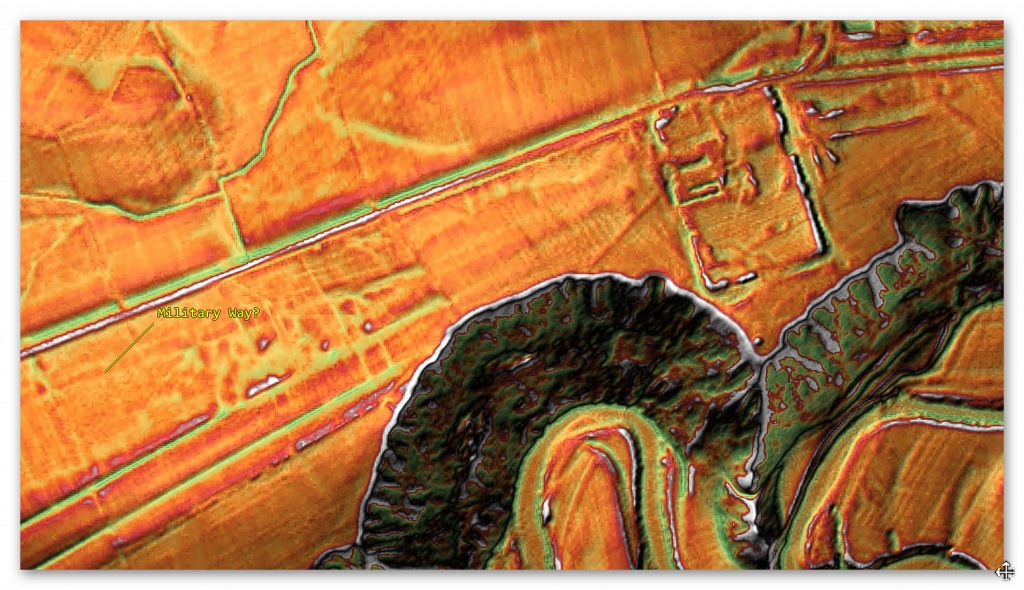

This section is also of interest as it is the first section to claim that it had a road incorporated into the design – “The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known throughout this section.” – HE: 1010944.

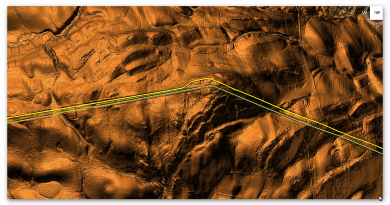

There is a linear feature on the LiDAR map which is claimed to be a Roman Road (Military Way) on OS maps. But when looking at the scale of construction compared the the substantial banks of the Vallum it questionable to its use? If you wanted to have a road to patrol the Wall would you not use one of the two raised banks of the vallum as they already exist? The evidence suggest not only was this construction very minor but leading nowhere in particular and at best joining on to the bank of the Vallum near the Roman Station?

The next incorrect assumption is found in HE section 101010994: “Excavation by Richmond from 1928 onwards showed that the vallum skirted the fort to the south.” – the LiDAR map clearly shows that the Vallum (South)ends by the edge of the River Valley and the northern Ditch was reduced even further to maybe entre the Station or the Station was built over the Vallum – it certainly does not go south as shown on the OS maps and the ditches found were part of the Station construction.

The flyover of this section (I) shows that the Vallum disappears each time it enters the Valley indicating that at the time of construction it was full of water – this supports my Post _Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and possible prehistoric dating of aspects of the Vallum which the Roman reused. This reusing of prehistoric features is not only limited to the Vallum in this section. To the north of the Wall there is a claimed Roman Road (Maiden Way) which seems to be a prehistoric Dyke that has been reused as a road later in Roman history.

Name: Maiden Way Roman road from B6318 to 450m SW of High House, Gillalees Beacon signal station and Beacon Pasture early post-medieval dispersed settlement

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1018242

The monument includes the earthworks and buried remains of a 6.58km length of the Maiden Way Roman road together with the earthwork remains of Gillalees Beacon Roman signal station, also known as Robin Hood’s Butt, and Beacon Pasture early post-medieval dispersed settlement.

The Maiden Way connected the Hadrian’s Wall fort at Birdoswald with the fort at Bewcastle 9.6km to the north. After leaving Birdoswald the road climbs gradually over Waterhead Common and Ash Moss to its highest point on the moorland of Gillalees Beacon where, a short distance south of the summit, remains of the Roman signal station stand. Beacon Pasture settlement overlies the Roman road and lies on the moorland a short distance south of the signal station. Construction of Birdoswald and Bewcastle forts commenced during the early 120s AD and the road connecting the two forts must also have been built at this time.

Where the road survives as an earthwork it can be seen either as a raised bank known as an agger upon the top of which the road surface was built, or as a hollow way where erosion of the road surface may have occurred or where the Roman engineers have taken the road through a cutting.

It is also visible as a terrace running diagonally down the steepest hillslope in order to ease the gradient. Flanking ditches for drainage purposes ran either side of the road; where not infilled by natural processes these ditches survive as earthworks. Where they are infilled their location can frequently be identified by changes in the vegetation cover where the deeper, damper soil has encouraged a lusher growth. The finest surviving stretch of agger and flanking ditch lies a short distance north of the B6318. Here a length of agger approximately 200m long measures 10m wide at the base and 5m wide at the top and survives up to 0.8m high. The western ditch at this point measures 2m wide by 0.2m deep. Limited excavations of the road further north have shown it to be formed of two courses of large stones laid flat over which a layer of small stones was laid to form the road’s metalled surface. The road was found to be well cambered and has large kerbstones.

These excavations also found that the width of the road surface was not constant and varied between 3.7m and 4.6m. In places, particularly on the higher moorland, the road and its ditches lie buried beneath vegetation cover and no surface remains are visible. Here the course of the road can still be followed quite clearly where modern drainage channels have been cut through it exposing the road’s stone foundations.

Gillalees Beacon signal station lies immediately west of the Roman road. It survives as a rectangular earth and stone mound up to 2.5m high surrounded by a shallow ditch with a causeway on the east side which gave access directly from the road. Antiquarian investigation found the stone-built structure to measure approximately 6m by 5.5m externally with walls standing ten courses high. The signal station is positioned to be in full view of Birdoswald fort 6.5km to the south and its function would have been to rapidly convey information to the fort garrison if an enemy was approaching from the north. Beacon Pasture early post-medieval settlement consists of three rectangular enclosures, one north of and two south of the Roman road. The house was originally built of stone and is now visible as a turf-covered platform of stone tumble measuring 13.5m by 6.7m. It lies alongside the road overlapping the edge of the northern enclosure and its position adjacent to the road indicates that this part of the Maiden Way remained in use during the early post-medieval period.

The southern enclosure measures 44m by 29m and contains ridge and furrow, indicating that arable cultivation took place here, while the smaller northern enclosure contains lazy-beds (raised earthen mounds) about 1.5m wide on which crops were grown, and thus also attests to arable cultivation. The central enclosure measures 34m by 32m and is interpreted as a stockpen. The settlement had been abandoned by 1854. Between NY60286811 – NY59886877 the protection follows the actual line of the road and not that suggested by the Ordnance Survey. The road is visible as an earthwork between NY60286811 – NY60136831 and between NY59906865 – NY59886877. Between NY60136831 and Slittery Ford at NY59896862 the road is interpreted as surviving as a buried feature.

If we look at this suspected Roman Road we see that like the Vallum is disappears into the river valley or that it is actually diverted as it comes in contact with the river valley.

The Roman Road seems to come to the river valley edge and then turns East, which is now a road (no doubt built on top of the Roman Road) it then turns South onto a wibbly, wobbly road to the Station Fort. There is absolutely no evidence that the Roman Road goes straight to the Fort across the River Valley indicating that Water was still present in Roman Period at the time of construction.

It is clear from the description of the Roman Road this is something built on top of a existing prehistoric feature “Where the road survives as an earthwork it can be seen either as a raised bank known as an agger upon the top of which the road surface was built, or as a hollow way where erosion of the road surface may have occurred or where the Roman engineers have taken the road through a cutting.” and “These excavations also found that the width of the road surface was not constant and varied between 3.7m and 4.6m. ” – Like the Vallum and the suggested Military Way, what we are seeing is a prehistoric feature that the Romans have adapted.

To understand the problem with Hadrian’s Walls history read our article HERE.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.