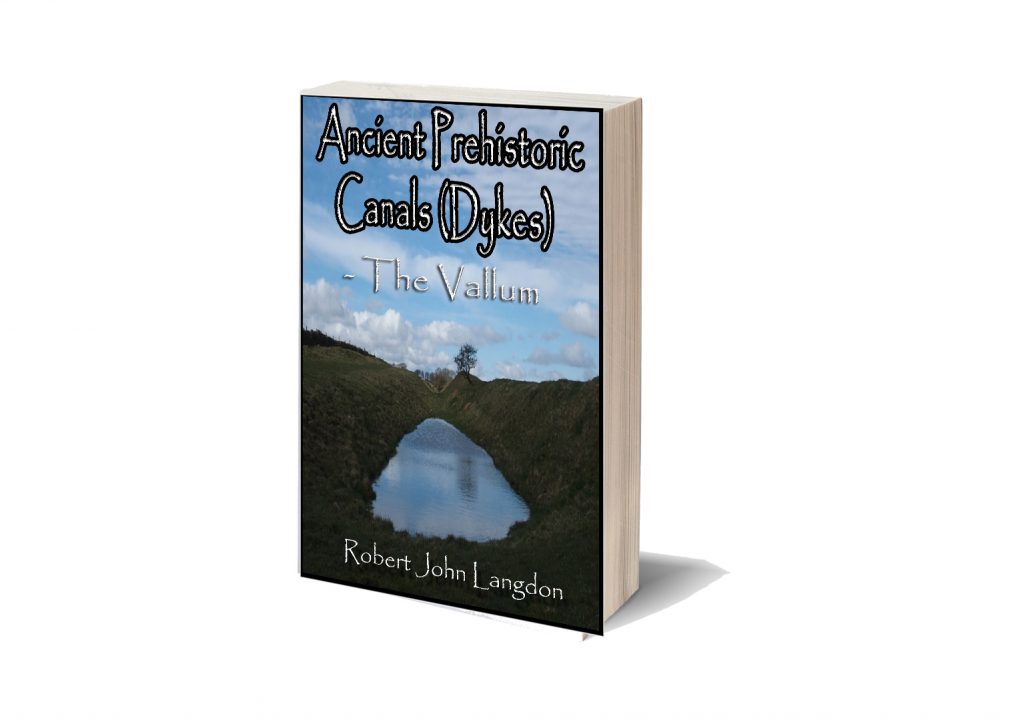

The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

The first ever detailed survey of the Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall proves conclusively that the Roman’s built of an existing ‘DyKE’ structure to move quarried materials and provide stone to Hadrian’s Wall. The details of the survey are contained in a New Book called ‘Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – The Vallum’ now available on Amazon.

Traditional archaeologists and archaeological establishments like English Heritage suggest that:

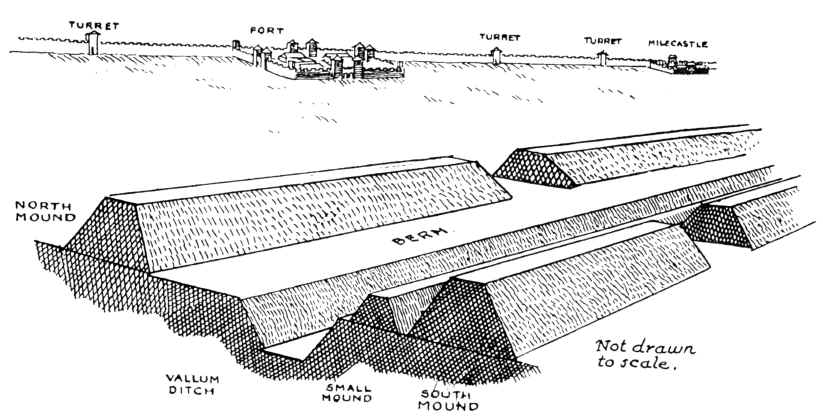

The Vallum is a massive earthwork constructed shortly after Hadrian’s Wall itself and lying just south of it. Many visitors confuse the Vallum with Hadrian’s Wall itself because it’s such an obvious and impressive feature in the landscape.

In fact, the Vallum is made up of several different elements – a ditch around 6 metres wide and 3 metres deep; two mounds either side of the ditch about 6 metres wide and 2 metres high and set back from the ditch by around 9 metres; and often a third mound on the southern edge of the ditch. The whole complex is around 36 metres across. Usually, the Vallum runs close behind the Wall but in the rocky and hilly central section the Vallum lies up to 700 metres from the Wall.

Crossing points seem to have been located south of each of the forts along Hadrian’s Wall and near several of the milecastles. Evidence from the excavated Vallum crossing at Benwell in Newcastle shows these crossing points had impressive monumental gateways.

The Vallum’s purpose is unclear. Many archaeologists think it marks the southern boundary of a military zone with the Wall itself forming the northern boundary. This would have helped protect the rear of the Wall and its associated military installations, with civilian access being closely controlled. The gateway at Benwell supports this idea. The numerous gateways along the Wall at forts and milecastles suggest that the frontier was intended as much to control movement as to provide a defensive line. Traders would have moved goods across the frontier but their movements would have been controlled and their goods taxed.

Relatively soon after it was constructed, some 20 to 30 years perhaps, the Vallum seems to have lost its function – the mounds were cut through and the ditch filled in at fairly regular intervals. It was out of use by the time the forts along the Wall were re-commissioned in the late second century AD following the return of the garrison from the Antonine Wall.

Sadly, these ideas that have been constructed over the last 200 years are somewhat questionable. Within the book we look at associated aspects of this area like Military Way which was supposed to be constructed to patrol the so-called ‘Military Zone’ – to find that:

That over 50% of Military Way does not exist as a separate road, as described by archaeologists. Instead, the perceived road is fragmented and only becomes ‘alive’ as an independent road when the Vallum separates from the wall at any distance.

This might give us a clue to the function of this rough and wonky road, as the stone for the wall would have needed to be delivered by cart if the Vallum canal was not available.

As for the Stanegate that was supposed to connect to the main forts in the area as a ‘defensive shield’ we actual found that it is very little to no evidence of the ‘Stanegate Roman Road’, which (according to the current theory proposed by English Heritage) ‘consolidated as a frontier’ during the late first and early second century AD and helped crystallise Roman tactics and military expectations in the area.

This evidence is compounded when you release that of the 80mile border from coast to coast – Stonegate, at best, covers just 38.1 miles (47%) of the ‘defensive gap’, and hence suggestions of extension over and above the existing line existed (even without support from OS maps). Moreover, the research has shown the ‘raw’ Stanegate road without the ‘hidden’ parts below the B-roads – we are only looking at 20% of the declared road being visible on LiDAR maps.

Stanegate Road (when not part of an existing B-road system) is inconsistent in width and structure -moving from bank track to road with two ditches on each side to a ditch with two banks far from straight and usually starts and ends in ravens.

Most Forts and the Stanegate are not found to connect (with intersecting sub-roads) on only two occasions, and the rest show no connection. Moreover, later ‘temporary’ camps also did not connect with the road – which questions whether (a defence line) was its purpose.

Moreover, this would then question the ‘myth’ of using the Stanegate as a ‘boundary’ for withdrawing troops from Scotland in the first century AD is correct. And whether the River Tyne (which most of these Forts sit upon) was used as a more practical and effective boundary/defence.

This ‘myth buster’ will not surprise many in academia as it has been ‘hinted’ at for some time (but not acted upon it by updating the literature), as we see from Symonds et al.

“The question of whether a road even existed when the fortlets were founded is by default an existential one for the notion that they provided highway protection. But even if the metalled road does post-date the fortlets, a reasonably robust thoroughfare of some form must have existed from at least the mid AD 80s to service Vindolanda. The question is not whether there was a road, but whether it was metalled when the fortlets were founded.” Symonds, M. (2017). Hadrian’s Wall. In Protecting the Roman Empire: Fortlets, Frontiers, and the Quest for Post-Conquest Security (pp. 95-132)

Moreover, even if Stanegate was not built as suggested, it exists in parts, and it looks prehistoric (by design) as it relies heavily on ravens that start and end sections of the Stanegate sections; its sunken structure in parts is unfamiliar to traditional Roman Road design.

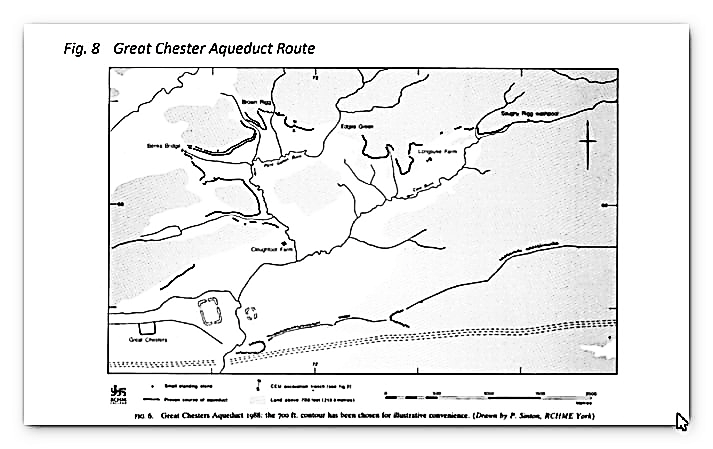

As for other famous ‘Roman Features Such as the Great Chesters Aqueduct, again we find not only is the origin questionable but as it located supposedly fully in ‘hostile territory – they its usefulness win conflict would be limited.

It is clear from the LiDAR research that the suspected Roman Aqueduct is not as it seems. This is not the first examination to spread doubt about the scale and origin of this feature in the landscape – MacKay, D. A. (1990). The Great Chesters Aqueduct: A New Survey. Britannia, 21, 285–289. Also shows an incomplete map of this aqueduct.

Mackey failed to find in their survey that the Aqueduct changed size, and the path suggested had no identifiable remains of the bridges required to make this Aqueduct work.

Our more detailed findings indicate that the topology of the aqueduct suggests that it would need to go uphill at several points without any powered assistance (like a siphon) and so is mechanically unsound. Our finding has found that the use of ‘Dykes’ in this area and some connecting to this Aqueduct feature is new. We have also shown that closer to the Fort it was supposed to supply, there were closed water sources which could be used and that the Fosse by the Wall was also a water supply.

We conclude that we found a prehistoric watercourse linked to their sophisticated ‘Dyke’ system. I would be bold to suggest that this was used for either agricultural purposes or maybe industrial, seeing the multiple sites of quarries associated and in the region of this feature.

When we look at the Conclusions and new data found about The Vallum we find that:

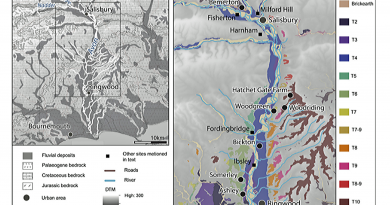

Total length found by LiDAR: 73,916m (45.93 miles) – 65% of the entire wall length

Total length Missing (by LiDAR): 42,339m (26.31 miles) – 36% of the Vallum length

Total number of Gaps in the Vallum – 49

Average Depth of the River Valleys (in gaps) – 7.75m

The total length of Vellum (including gaps) 116,255m (72.24 miles)

In comparison, Hadrian’s Wall is reported as 80 Roman miles or 73 standard miles in length.

Features

Within the 72.24 miles of the Vallum, we have identified – within 200m of the construction:

46 Springs (as specified by the 1800 OS maps series)

54 Quarries

14 Prehistoric Ancient sites

To judge if the frequency of these features are standard or an anomaly of the Vallum – we have measured two roughly parallel lines to the Vallum, one five miles to the north and the other to the south.

This mathematical exercise will give us a comparative average for these features in the environment within the locality:

Northern Test Line (within 200m)

12 Springs

25 Quarries

1 Ancient site

Southern Test Line (within 200m)

10 Springs

30 Quarries

3 Ancient Sites

Results

46 v 10 Springs – Vallum has 460% more Springs, that the norm

54 v 30 Quarries – Vallum has 180% more Quarries, than the norm

14 v 2 Ancient Sites – Vallum has 700% more ancient sites, than the norm

So, Are we seeing the use of prehistoric Dykes (linear earthwork) banks being utilised for a new purpose?

In the book we show that there are many ‘quarry sites’ along Stanegate Road and an increased number of ‘temporary’ forts, some of which have these quarries inside. Therefore, have archaeologists missed the point of not only the ‘temporary’ forts but the purpose for the road use and, consequently, why Hadrian’s Wall was built?

When the Roman Empire decided to invade any country (contrary to the traditional myth), it was to possess more incredible wealth. Britain was a wealthy (iron Age) island, perfect for conquest as it had rich commodities such as gold, silver, tin, lead, wheat, and enslaved people. Some of this mineral trading wealth is found in the quarries that surround this area and has been exploited since the dawn of trading (prehistoric times).

This may explain why so many unscheduled Dykes are found in this area and why many start/terminate within the quarries. Romans are the best adaptors in history when it comes to the assimilation of foreign assets, engineering and cultures – therefore, would it not have been prudent to take the existing infrastructure of Dykes and adapt them to make roads rather than starting from scratch? (we will see this in detail when examining the Roman Vallum).

These quarries needed a workforce to extract the minerals, housing, feeding facilities, and store the precious quarried materials. We have seen how this has been done in history by lightly guarded fortifications (places with wooden walls and armed guards) and is this what we see alone on Stanegate Road with the ‘temporary’ fort camps?

Eventually, these ‘warehouses’ would have been a target for raiding and robbery – so would it not make sense to eventually build a more substantial defence against robbers (non-enslaved picts of Scotland?) and is this the real reason that the Romans built Hadrian’s Wall and why it was moved just after 40 years to incorporate the quarries that are currently north of the Wall?

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE or on our PRESS RELEASE PAGE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.