DYKES of Britain

Contents

- 0.0.1 The most extensive study of the ‘Dykes of Britain’ in historical field and modern day LiDAR investigation has been completed on Offa’s Dyke and has found ‘extensive and conclusive’ evidence that Offa’s Dyke was not constructed for ‘Defensive’ or as a medieval ‘Boundary Marker’. Moreover, the results have found that it was not built at the time of the Saxon’s and Offa – but thousands of years earlier. Below is an extract of the dvd video that accompanies the Trilogy of books on ‘Prehistoric Earthworks’ that will be published in the Autumn of 2021.

- 0.0.2 Section 1 – North Savernake to Gore Copse – 1,995 metres long (6,650 working days – 20 men, 333 days).

- 0.0.3 Section 2 – Gore Copse to Shaw Farm, 4,325 metres long (14,416 working days – 20 men, just under two years).

- 0.0.4 Section 3 – Shaw Farm to Milk Hill (North), 3,821 metres (12,737 working days – 20 men, 1.74 years)

- 0.0.5 Section 4 – Milk Hill (north) – Sheppard’s Shore, 3,460 metres (11,533 working days – 20 men, 1.58 years)

- 0.0.6 Section 5 – Sheppard’s Shore – Morgan’s Hill, 5,290 metres (17,633 working days – 20 men, 2.41 years)

- 1 Product details

The most extensive study of the ‘Dykes of Britain’ in historical field and modern day LiDAR investigation has been completed on Offa’s Dyke and has found ‘extensive and conclusive’ evidence that Offa’s Dyke was not constructed for ‘Defensive’ or as a medieval ‘Boundary Marker’. Moreover, the results have found that it was not built at the time of the Saxon’s and Offa – but thousands of years earlier. Below is an extract of the dvd video that accompanies the Trilogy of books on ‘Prehistoric Earthworks’ that will be published in the Autumn of 2021.

This new TRILOGY will include case studies of both Offa and Wansdyke – here is an extract from the Wansdyke Case Study

According to Wikipedia, “Wansdyke consists of two sections of 14 and 19 kilometres (9 and 12 mi) long with some gaps in between. East Wansdyke is an impressive linear earthwork, consisting of a ditch and bank running approximately east-west, between Savernake Forest and Morgan’s Hill. West Wansdyke is also a linear earthwork, running from Monkton Combe south of Bath to Maes Knoll south of Bristol, but less impressive than its eastern counterpart. The middle section, 22 kilometres (14 mi) long, is sometimes referred to as ‘Mid Wansdyke’ but is formed by the remains of the London to Bath Roman road. It used to be thought that these sections were all part of one continuous undertaking, especially during the Middle Ages when the pagan name Wansdyke was applied to all three parts.

East Wansdyke in Wiltshire, on the south of the Marlborough Downs, has been less disturbed by later agriculture and building and remains more clearly traceable on the ground than the western part. Here the bank is up to 4 m (13 ft) high with a ditch up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) deep. Wansdyke’s origins are unclear, but archaeological data shows that the eastern part was probably built during the 5th or 6th century. That is after the withdrawal of the Romans and before the takeover by Anglo-Saxons. The ditch is on the north side, so presumably it was used by the British as a defence against West Saxons encroaching from the upper Thames Valley westward into what is now the West Country.

West Wansdyke, although the antiquarians like John Collinson considered West Wansdyke to stretch from south East of Bath to the west of Maes Knoll, a review in 1960 considered that there was no evidence of its existence to the west of Maes Knoll. Keith Gardner refuted this with newly discovered documentary evidence. In 2007 a series of sections were dug across the earthwork which showed that it had existed where there are no longer visible surface remains.

It was shown that the earthwork had a consistent design, with stone or timber revetment. There was little dating evidence, but it was consistent with either a late Roman or post-Roman date. A paper in “The Last of the Britons” conference in 2007 suggests that the West Wansdyke continues from Maes Knoll to the hill forts above the Avon Gorge and controls the crossings of the river at Saltford and Bristol as well as at Bath.

As there is little archaeological evidence to date the western Wansdyke, it may have marked a division between British Celtic kingdoms or have been a boundary with the Saxons. The evidence for its western extension is earthworks along the north side of Dundry Hill, its mention in a charter and a road name.

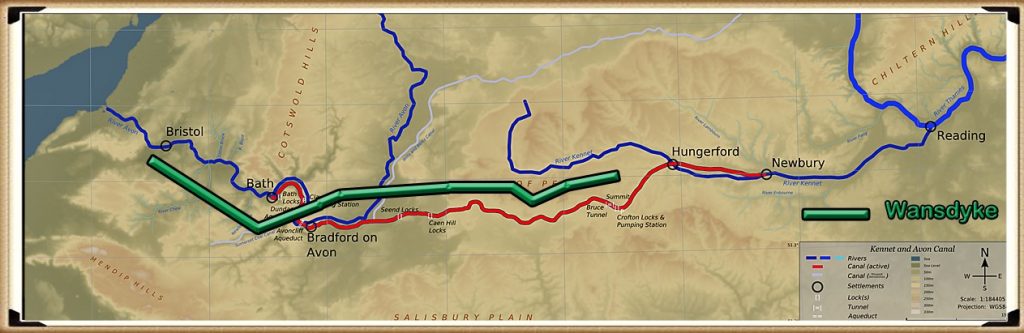

| Figure 10- Map comparing Wansdyke (green) to the Kennet and Avon canal |

The area of the western Wansdyke became the border between the Romano-British Celts and the West Saxons following the Battle of Deorham in 577 AD. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the ‘Saxon’ Cenwalh achieved a breakthrough against the British Celtic tribes, with victories at Bradford on Avon (in the Avon Gap in the Wansdyke) in 652 AD, and further south at the Battle of Peonnum (at Penselwood) in 658 AD, followed by an advance west through the Polden Hills to the River Parrett. It is, however significant to note that the names of the early Wessex kings appear to have a Brythonic (British) rather than Germanic (Saxon) etymology”.

Later scholars have often questioned the accuracy of the descriptions given by these antiquaries such as assertions that Wansdyke reached the Bristol Channel (Fox and Fox 1958) and even Asser’s statement that Offa’s Dyke ran from sea to sea (Hill and Worthington 2003 106). While some antiquarians were probably exaggerating the size of earthworks, we must be cautious of dismissing descriptions of the dykes from before they suffered the ravages of the Agricultural Revolution.

Some scholars went beyond merely describing the dykes and tried, often erroneously (with hindsight), to link them with known historical events like the Belgic invasions mentioned by Caesar or Caesar’s own invasion (Warne 1872 4-10; Guest 1883; Handford 1951 119-40). Among these early, rather speculative descriptions, the work of the Wiltshire historian Sir Richard Colt Hoare (1758-1838) stands out, not only in terms of the quality of his survey work but also his ability to differentiate between features of different dates, for example by realising that the central section of Wansdyke was actually a Roman road (Hoare 1812; Hoare 1821).1

Boundary Markers & Defensive Structures

The archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler produced an analysis of the dykes of southeast England and, like Fox, suggested that they were not primarily military structures but political boundary markers facing post-Roman Britons centred on London (Wheeler 1934 261).

Osbert Crawford’s 1953 book on Wansdyke analysis of the dykes as either military-political (with no clarification of what that meant in practice) or in respect of the coastal dykes (like Dane’s Dyke at Flamborough Head or the Cornish dykes) calling them beach-heads He also made no attempt to group what he termed defensive linear earthworks by period; in his list of them given as an appendix to his field archaeology guide, he includes prehistoric and Anglo-Saxon dykes together with undated earthworks (Crawford 1936 240-53). These shortcomings are easy to criticise now, though, at the time, Crawford’s work was exceptional.

The problem with Crawford’s work is that Wansdyke has a gap in the middle of the defence/boundary and no explanation for the lack of Dyke?

Figure 11 – Crawford Political Boundaries

One of the fundamental weaknesses of this earthwork as a defensive structure is the fact it just stops in a middle of a field on the Eastern side of the Dyke.

A series of excavations carried out by H. Stephen Green on Wansdyke in the late 1960s provided the first opportunity to apply both snail and pollen analysis to dyke studies (Green 1971). While the evidence for snails was largely inconclusive, the pollen samples (analysed by GW Dimbleby) suggested that central parts of the eastern half of Wansdyke passed through a pasture. The pollen evidence from the eastern end of Wansdyke suggested the presence of nearby woodland (Savernake Forest), though it did not prove or disprove the hypothesis that it was an impassable barrier that protected the eastern flank of the dyke, as Fox had postulated (Fox and Fox 1958).

There have sadly been very few excavations or thorough investigations of these dykes (remembering there are over 1000 dykes in Britain), one of the earliest excavations was overseen by Lieutenant-General Pitt Rivers, who excavated Wansdyke at Shepherd’s Shore, Devizes.

Although most of the findings and accounts lack scientific accuracy, we find some aspects that support the dating of dykes earlier than the current ‘expert’ theories of Saxon Britain. In one of his cuttings through the ditch and bank he noted that “At Wand’s house, there is a break in the line of the Dyke, which is occupied by the site of the Roman station of Verlucio, where quantities of Roman pottery are scattered on the soil”.

Pitt-Rivers also found vast amounts of pottery and iron nails in the bank of Wansdyke further down the earthwork. Isn’t it more likely, that the Romans placed their settlement actually on the Dyke as it may have still held water two thousand years ago and, looking at the positions of the findings, actually cleaned it out, which would allow them to take and receive supplies by boat to and from the river Kennet? Moreover, he noticed that at Sandy Lane and the Roman settlement in Spye Park – the river was still running inside the Dyke!

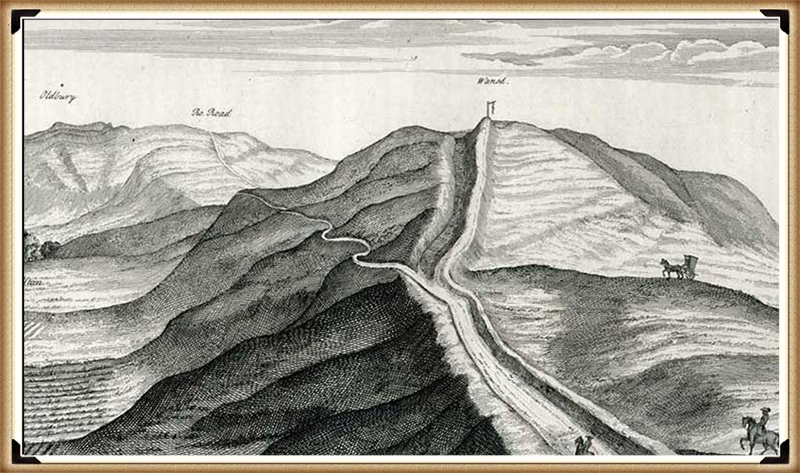

| Figure 12- Stukeley’s Map of 1724 showing the Roman road ‘sitting on top’ of the Wansdyke ditch |

In fact, within his excavation of the dyke we noted that:

“Very little ‘silting’ had accumulated on the escarp, but in the ditch, it had collected to a depth of about 3 feet in the centre” – showing that the main purpose for the dyke was to take water like a canal.

The final proof of the fact that the Dykes predate the Roman invasion can be found strangely with empirical evidence from a drawing produced by the first British archaeologist William Stukeley in 1724. The Roman road is clearly made on and above the Wansdyke ditch and then cutting through the Dyke’s bank – this is impossible to do if the bank and ditch were built AFTER the road (archaeologist and historians, please take note!!).

If we look at Wansdyke on an OS map, to the East, the ditch ends in the middle of nowhere, just before the forest of Savernlake. The question that archaeologists fail to answer is ‘why stop there’?

If you continued another 6km, you would have reached water – a natural boundary (remembering you have already cut 19km), or just turn south, and that’s a mere 3km. To the west, it’s even worse, you could go south again and connect to the river, using that as a natural defensive boundary, but no – it just stops dead.

If you were to attack the ditch, you would be mad – as you just walk around it as the German’s did on the Siegfried line at the outbreak of World War II.

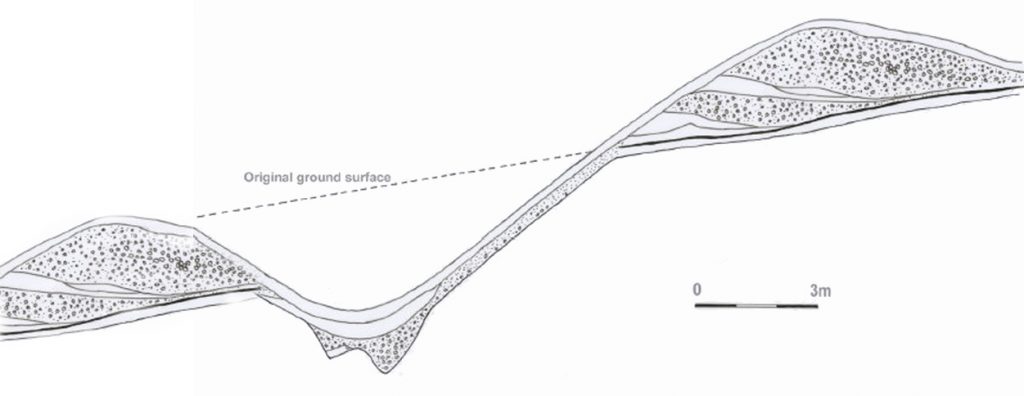

The final proof of that the ditch is not defensive can be found in its method of construction. Going back to the work of Pitt-Rivers, he produced a series of detailed cross-sectional drawings to support his investigation. These drawings showed two significant findings: firstly, the ditches fill was spread over both sides of the ditch (one side slightly more than the other) – you would not do this if it’s a defensive feature as you would want all the ‘high ground’ on your side to help defend. This kind of slightly even distribution we see on Iron Hill ditches and other featured sites such as Durrington, Stonehenge, and particularly Old Sarum. In fact, the only site we don’t see this happen is at Avebury.

| Figure 13 – Wansdyke East section just stops – the forest would not have been there during Roman times and hence the roman road going through the centre |

Secondly, and most importantly, the bottom of the ditch is flat, again just like Stonehenge, Avebury and Durrington – it could also be Old Sarum, but sadly nobody has done an excavation of the ditches to date.

| Figure 14- Pitt-Rivers cross section shows ditch fill spread on BOTH sides – so not defensive |

You do not make the bottom of a ditch flat if used as a defensive ditch or a land marker (you’re doubling the time it takes to make a ditch). On Pitt-River’s excavation plan, the flat bottom is a third of the width of the ditch.

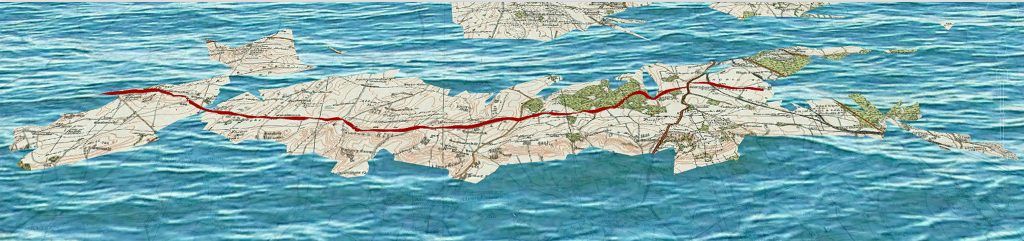

The Kennet and Avon Canal (Fig. 93) is a waterway in southern England with an overall length of 87 miles (140 km), made up of two lengths of navigable river linked by a canal. The name is commonly used to refer to the entire length of the navigation rather than solely to the central canal section. From Bristol to Bath, the waterway follows the natural course of the River Avon before the canal links it to the River Kennet at Newbury, and from there to Reading on the River Thames. Quite remarkably, Wansdyke was constructed just 3 km north of the Kennet and Avon canal. If it was a prehistoric waterway, it would have achieved the same purpose of joining the River Thames to the Bristol Channel but some 6-8K years before the Victorian’s great canal system.

Now let us consider the human resources it needed to create such a structure. At 33 km in length (33,000m), its volume can be calculated as about 618,750 cubic metres of chalk (if it is 2.5m deep and 7.5m wide as an average). This is the approximate volume of material removed from the ditch. This is five times more than what was excavated at Avebury and two and a half times larger than Silbury hill. So, according to Atkinson’s calculations at Silbury Hill, we are looking at 45 million working hours, which equates to 100 people working for 12-hours every day 365 days a year for 102 years.

It took the Victorians one hundred years to build the Avon & Kennet Canal using metal tools and steam engines. Moreover, the Victorian canal was only 1.3m deep and 6m wide – the ancient canal ditch is in places twice as big as the Victorian counterparts. So, whoever built it must have spent many years completing this task – which suggested it was essential at the time of construction.

If you study a geological map of this area, you will be struck by the endless twisting rivers that once flowed on and around the Wansdyke earthwork. These are called ‘superficial deposits’ and consist of sand, silt and pebbles. This is evidence that ‘once upon a time’ rivers formerly flowed in these what we call today’ dry valleys’ (Palaeochannels), and the clue just like the name for these earthworks (Dykes) is in the title.

If we add the known prehistoric groundwater rivers (based on our hypothesis) to the map of this great ditch, we find that springs would feed the ditch naturally, flooding it – and there you have yourself a canal. This 21-mile canal links (just like the Avon & Kennet) the river Thames to the Bristol Channel. And there can be only one reason for this massive undertaking (boat travel for the purpose of trade) just like the Victorian ancestors would achieve some six to eight thousand years later.

However, the most miraculous revelation about these Dykes is the fact that the builders had a greater knowledge of hydrology than even today’s engineers and geologists, for the weakness and final demise of the canal system in Britain was the fact they were very slow (the Victorians had to build at least one lock per mile of the canal to keep in the water high) the Kennet and Avon have over 100 locks. The original prehistoric channel had none as it relied on the natural groundwater table levels to fill the canal. Therefore, it was straighter and shorter in length than the Avon & Kennet, which would have allowed them to travel from the Thames to the Bristol Channel almost a hundred times faster than the Victorian barges.

Moreover, if you find this difficult to believe, you should bear in mind that there are over 1,000 dykes in Britain; a majority, 90%, are straight and less than 1km in length. To date, every single dyke we have investigated has underground links to these prehistoric rivers created from the ‘post-glacial flooding’ after the last ice age.

Furthermore, some of these Dykes are linked to ancient sites directly, as shown in this case study confirming the age of these earthworks. For if we add the known prehistoric groundwater rivers, we find out why this remarkable canal has two dead ends. For West side of the dyke is in the middle of a prehistoric island, which perfectly cuts the island into two and would allow boats to sail from one end of the island to the other in the Mesolithic. At a later date, an extension was added (as the water table levels dropped) to keep it connected to the Bristol Channel in the Central and West Section.

This explains why the Central section is different and straighter than the Eastern section of Wansdyke and is often referred to as a ‘Roman Road’ on OS maps. Moreover, it proves beyond doubt that it was not built as a boundary marker of a defensive ditch as it would have had a 6-mile gap in the middle of the earthwork.

This Dyke was built over hundreds if not thousands of years, which reflects not only the engineering and organisational skills of this advanced civilisation but, moreover, the sophistication and complexity of this trading society.

Figure 15 – East Wansdyke was an island in the Prehistoric Period with section analysis to follow – DYKES of Britain

East Wansdyke Maps in Detail (from East to West)

Section 1 – North Savernake to Gore Copse – 1,995 metres long (6,650 working days – 20 men, 333 days).

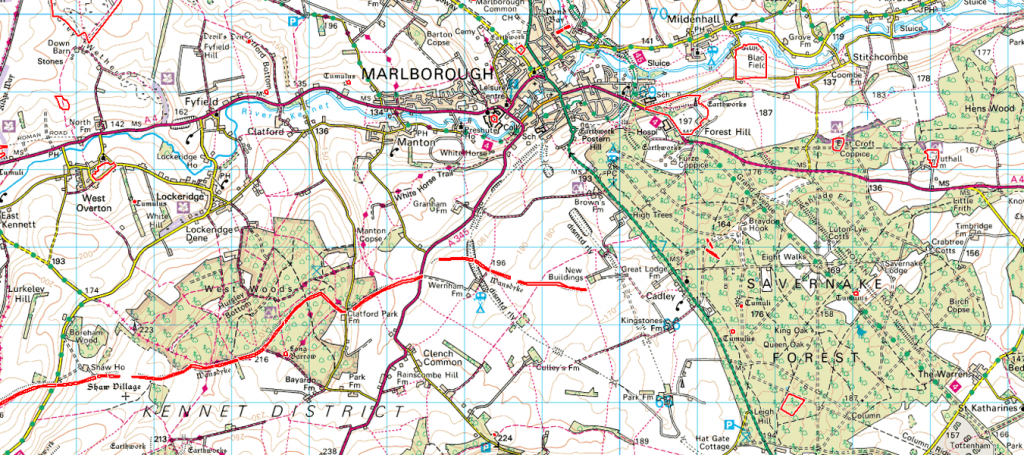

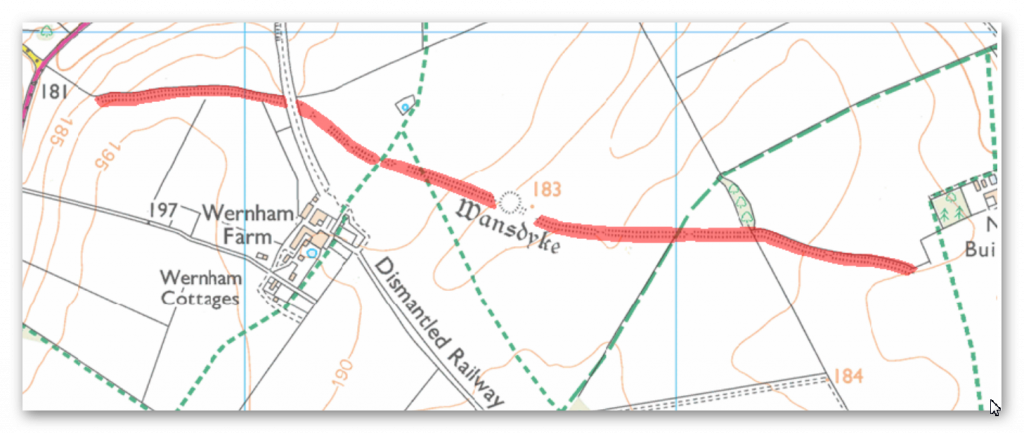

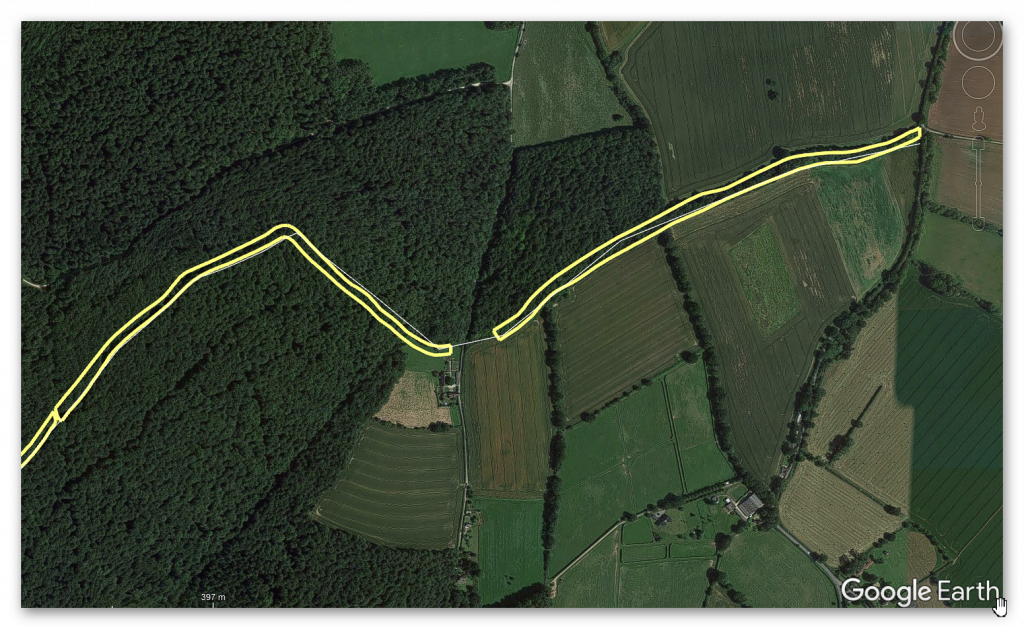

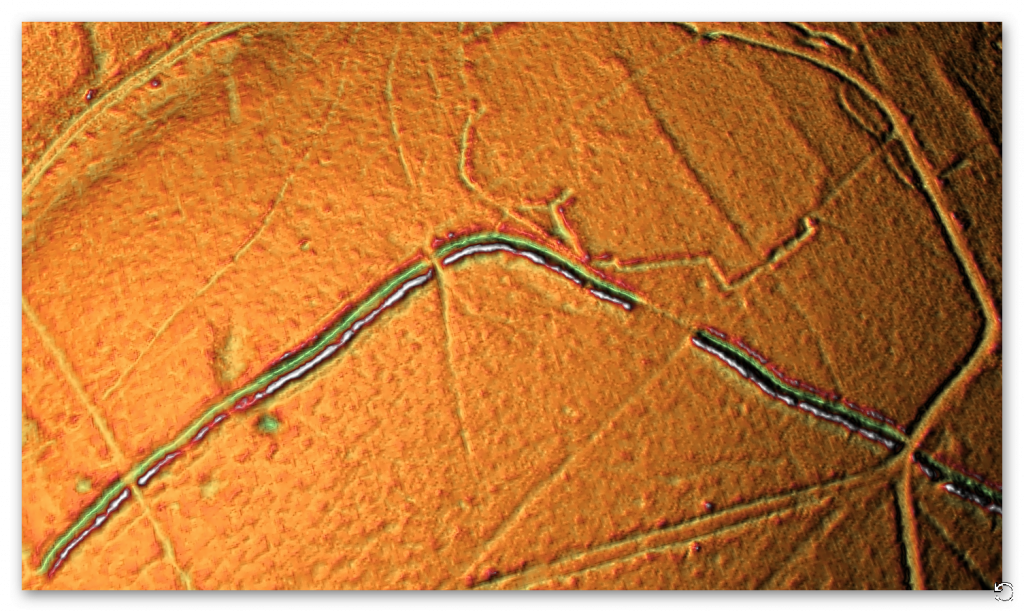

Figure 16 – Wansdyke NW of Wernham – with Mesolithic Water Levels

No information is available from Historic Monuments England – no survey or excavation has been undertaken.

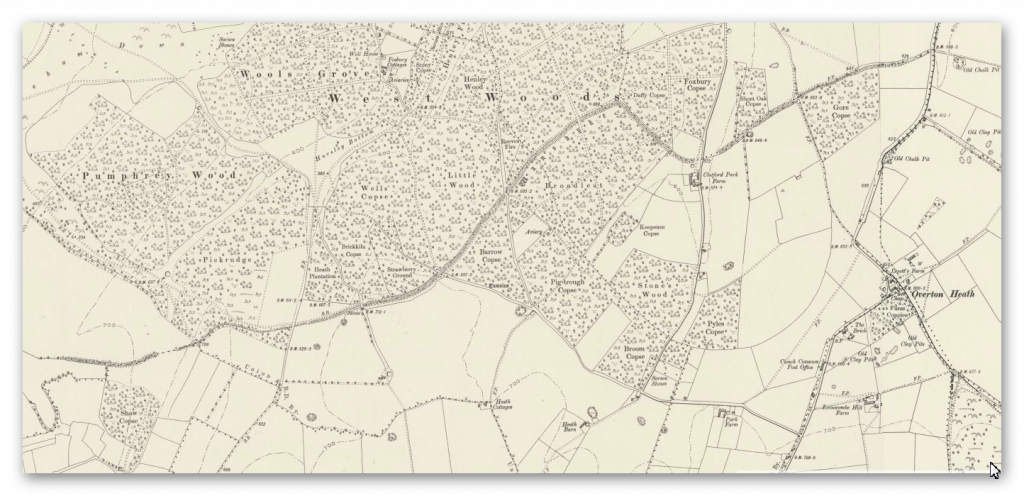

Figure 17 – Current OS Map

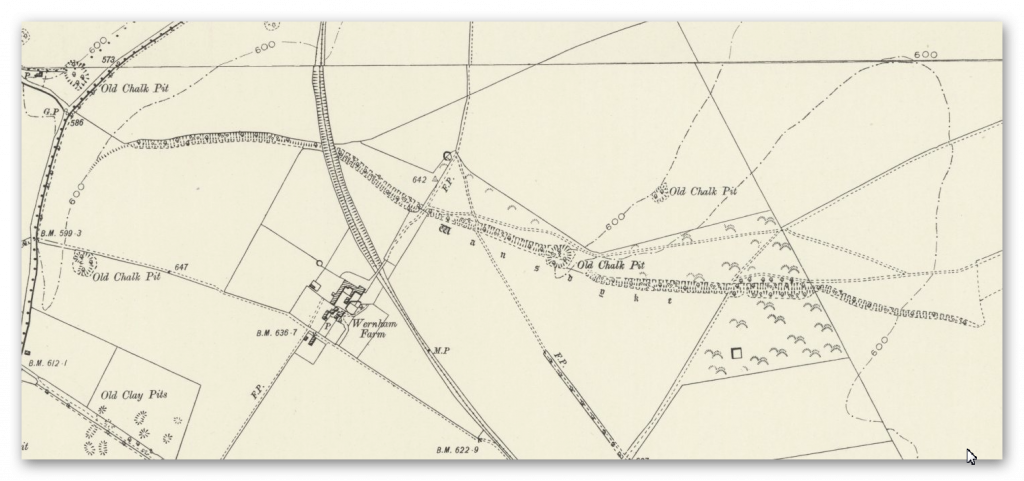

Figure 18 – 1800 map

Figure 19 – Geological Map showing ‘Clay with Flints’

The maps tell us very little, sadly, except that the subsoil of clay with flints is ideal for canals and water retention – so even if the water table fell, the clay would and could be used like a dew pond as a liner for rainwater retention. We estimate at a rate of 0.3m per day this section of the Dyke would have taken 6,650 working hours to construct or 20 men working 333 days – this is based on one man cutting 0.3m per day (Ditch down to 2m and bank) although Fowler used 0.1423 metres per hour and claimed 1,000 men built the ENTIRE East Dyke in 30 days working 10-hours a day 6 days a week??

This ridiculous claim I have discounted as even with modern tools, it would be too demanding, and the logistics of feeding, mending tools and housing 1,000 men was not taken into account. Therefore, we have used a more reasonable number of men (20) ‘digging’ as you would probably need double that number to feed and maintain and clear (it was mostly woods and forests in the past) in front of the diggers.

Quarry Pit

On fig 18. A feature called ‘firs’ is a gap on the OS Map – there is a strange quarry pit (no relevant substances under the surface to quarry?) – this pit, as shown in Fig. 16, is two metres deep and probably built at a later date to the original ditch. Are we looking for a hole to find the groundwater to keep the canal working with fresh water? As we will discover, this is not the first pit cut deep on the line of Wansdyke.

Figure 20 – Water at the top of one of the highest places of Wansdyke – and yet defying public opinion it doesn’t run down the hill to the valley?

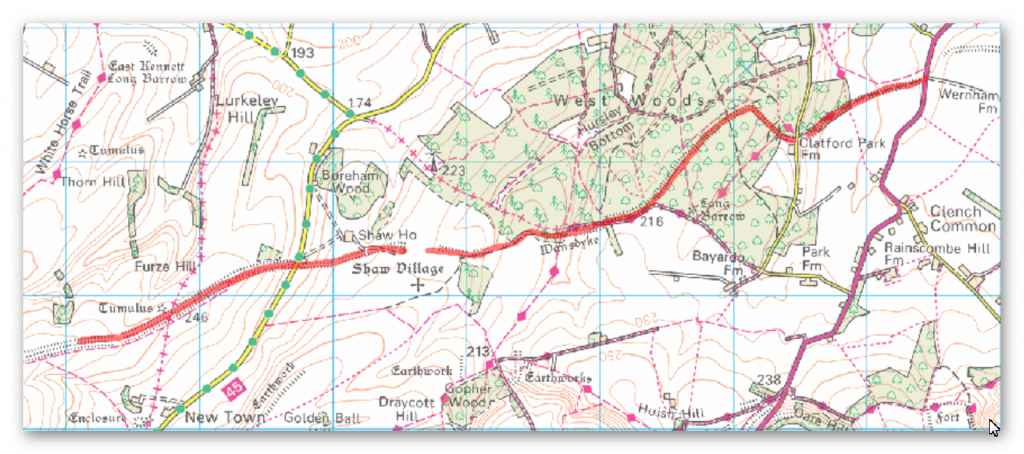

Section 2 – Gore Copse to Shaw Farm, 4,325 metres long (14,416 working days – 20 men, just under two years).

| Figure 21 – S of Furze Hill to Marlborough – Pewsey Roads |

| Figure 22 – OS map of Furze Hill to Marlborough |

Figure 23 – Geo Map of Furze Hill to Marlborough – Clay with Flints

| Figure 24 – 1800 map of Hill to Marlborough |

| Figure 25 – View of Wansdyke kinking at right angles for no apparent reason |

No information is available from Historic Monuments England – no survey or excavation has been undertaken.

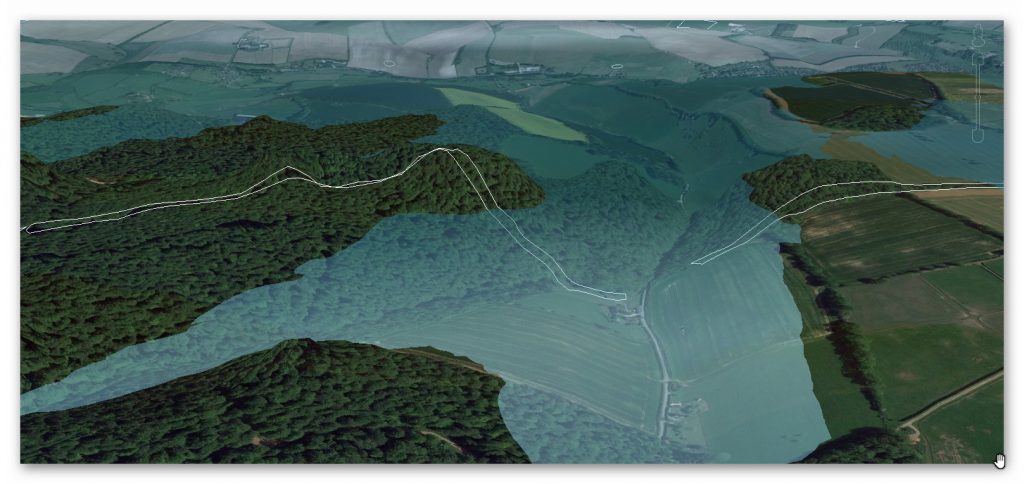

What is clear from the route of this section of Wansdyke is not straight at all – in fact, it works against the topology to bend at 90 degrees in some place and dip down unnecessarily into a valley rather than taking the high ground. Moreover, it heads into a forest that would be impossible to see as a marker, and as a defensive earthwork would be negated by the overhanging trees?

| Figure 26 – The line of Wansdyke is not remotely straight |

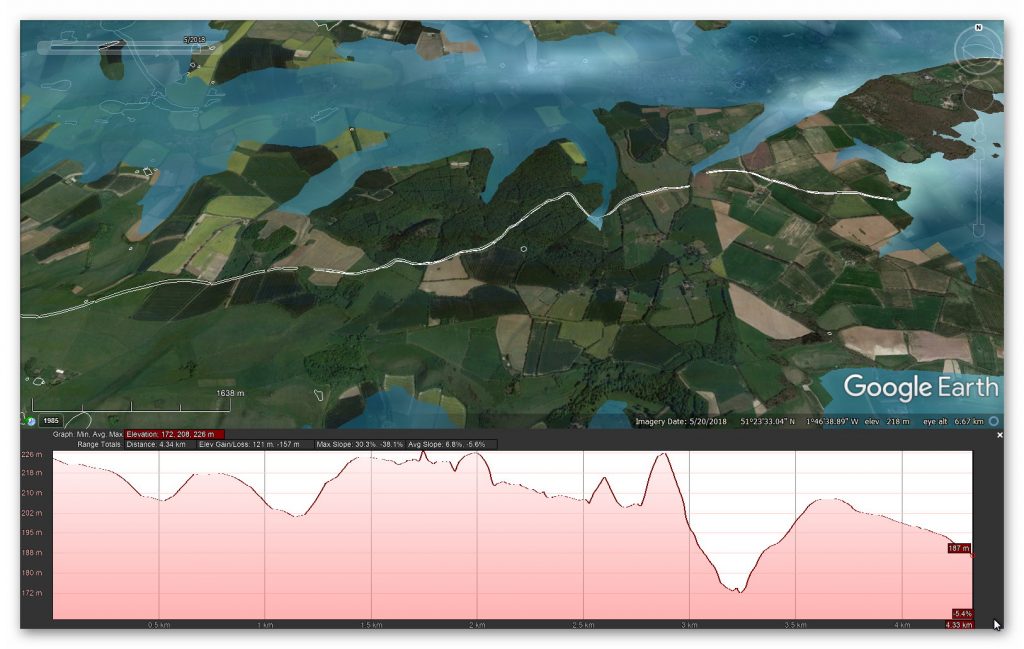

But this wild undulations into valleys also causes problems for my hypothesis as a canal. How could a canal move up and down significant gradients without locks?

Well, the answer obviously is that they can’t – but the answer to this problem is in the detail, for if you look again at this part of Wansdyke going into an old dry river valley, you see something archaeologists miss – it stops!!

We saw from the transition from the first part of Wansdyke to the second a gap, which looks like a piece filled in by farming; there were two other gaps the first was a later road cutting through and then a railway doing the same.

| Figure 27 – Dry River valley would have been flooded – so boats went across not down |

On the Dry river valley aspect of this part of the canal has a massive gradient if it went to the bottom and would make moving a boat very difficult. But what we do see is evidence of the dyke stopping before reaching the bottom. This also discounts both this earthwork as a marker and especially as a defensive feature.

The termination of this feature and at what point is at best a guestimation as no excavation work has been undertaken on this part of the Dyke. Moreover, this dry river valley in prehistoric times would not be ‘dry’ but full of water as shown in the illustration (Fig.25).

This would make sense to the termination on the right as it would initially end at the shoreline of the river. If this was the case, the simple answer to the problem is that at that point, you took the boat across the river, so the gradients are small to non-existent.

But why is there a continuation of the Dyke down the valley?

This can best be answered by understanding what happened to this earthwork once the waters started to fall in the Neolithic Period.

Logically, as the waters fell, the ditch would have been extended to meet the lower water level until the slope was too extreme to continue and was abandoned. Later once the river had completely dried up (and consequently the rest of the Dyke as the water table would have universally fallen), the natural road (the bank of the Dyke) would be used as a road.

Excavations of similar features (also contained in this book) have shown that the bank reduced in height and become flattered like a road and hence wider. To use this road on a permanent basis, the builders adapted the dry river valley element (which would still be boggy for many centuries after the river disappeared) by adding to the bank by removing soil from the ground – but on both sides, making the ditch element smaller and more shallow than the rest of the Dyke and to both sides.

The result of this work looks like a loss of the deep ditch but is more likely a change in its structure – which again is seen clearly on parts excavated in other Areas and dykes but impossible to see her without excavation.

Long Barrow

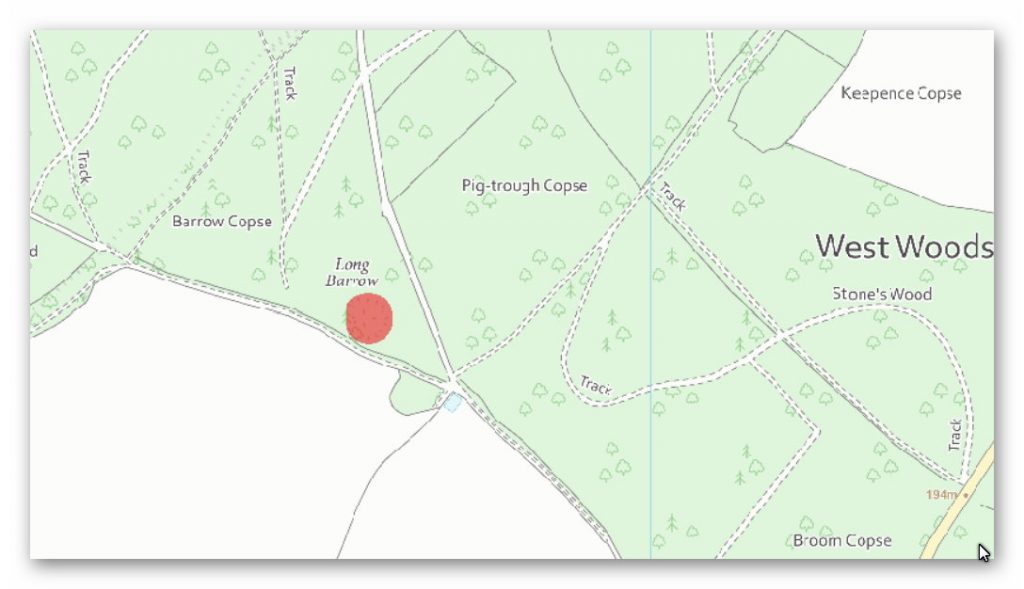

Figure 28- Wansdyke section 2 Long Barrow

An interesting associated feature can be found just 200m south of Wansdyke section 2, a Long Barrow.

“The monument includes a long barrow set above the floor of a dry valley in an area of gently undulating chalk downland. The barrow mound is ovate and orientated east-west. It is 40m long, 27m wide and stands to a maximum height of 3.5m. Flanking the barrow mound to the north and south are ditches from which the material used to form the mound was quarried during the construction of the monument. These survive as earthworks 8m wide and 1m deep” – Historic England

What should be noted is it’s ON THE SHORELINE of the ‘Dry Valley’ as shown from the suggested water level on our illustration. This is reflected by the ‘track’ that mimics the shoreline from the water. We can also see that at a later date, the Dyke was used for the same purpose of bringing the bones of the dead from a reincarnation site to the Long Barrow.

This confirms the river levels at the time of construction and the previously speculated gap in Wansdyke by the river valley top.

Flint Pits

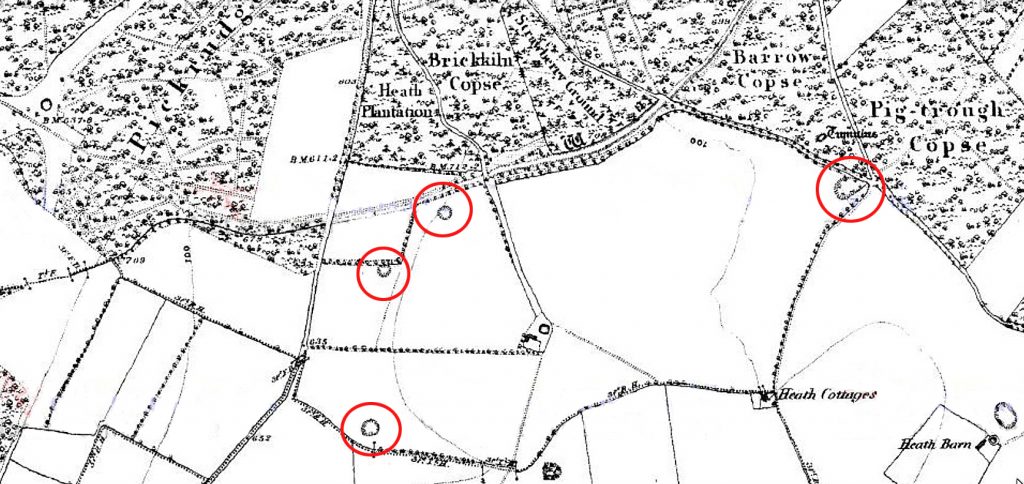

Another interesting feature near the Dyke is the ‘Old Flint Pits’ as a feature on the 1886 edition of the OS map but not recorded by Historic Monuments Dept.

Figure 29 – Old Flint Works in red

As this location is over 3-miles from Marlborough with plenty of open space closer to the town to obtain flint for the Middle Ages – I would expect these relative close works and activities to relate to the time of Wansdyke.

Section 3 – Shaw Farm to Milk Hill (North), 3,821 metres (12,737 working days – 20 men, 1.74 years)

Round Barrows

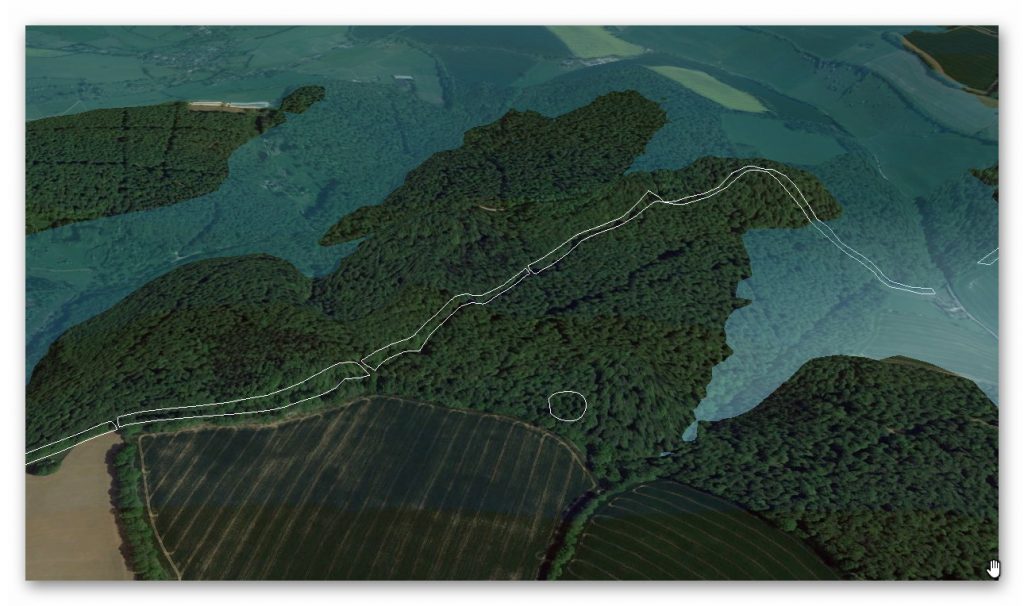

Figure 30 – Wansdyke section 3 – Round Barrows

Amazingly, along a strip between New Shaw Farm and Red Shore we find a series of barrows of which only one still exists.

The monument includes a bell barrow set below the crest of a steep north-east facing slope in an area of undulating chalk downland. The barrow mound stands to a height of 0.5m and is 20m in diameter. The surface of the mound comprises large flint nodules, and some worked flint. Surrounding the mound is a ditch from which the mound material was quarried. Although this has been infilled over the years and is no longer visible on the ground, it survives as a buried feature c.3m wide. Partial excavation of the barrow mound in 1970 produced cereal pollen grains suggesting early cultivation of the area. – Historic England

The OS map of the 1800s show this bell barrow as the last of the four nearest the Farm – the other three have clearly been ploughed out over time. What is of significant importance is the fact that Wansdyke and the barrows follow the same path, which gives us a chicken and egg scenario – what came first?

According to the ‘experts’ as these barrows are prehistoric in date, did the builders of the Dyke decide to cut this ditch by their side for reasons unknown? Or is it more likely that the ditch existed first and the barrows were constructed after the completion of the works?

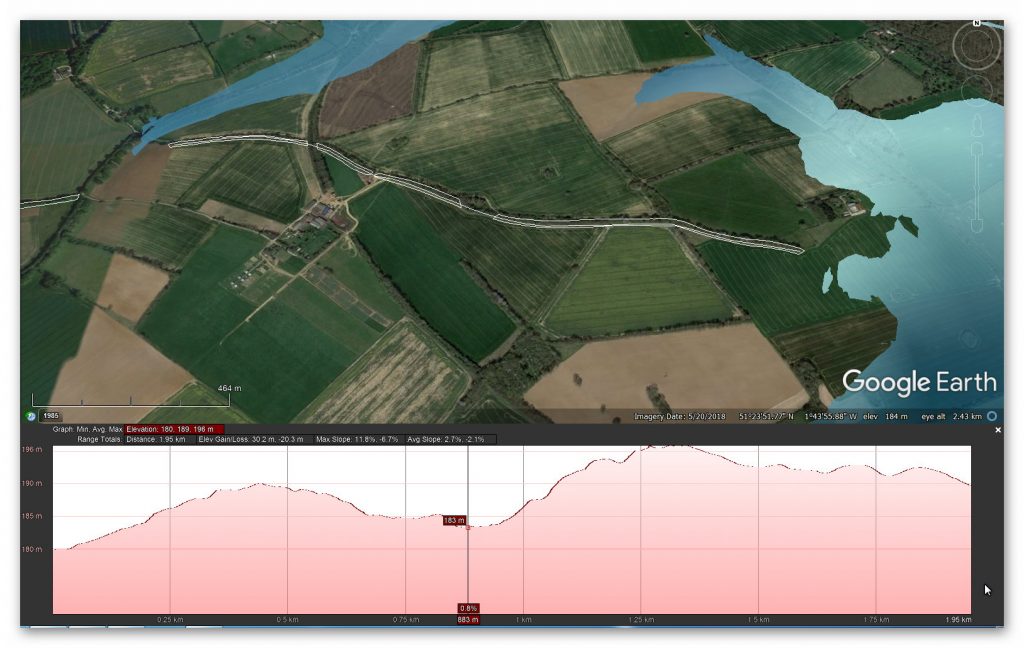

If we look at the satellite map – during the dry season do, we get a glimpse of these features still on the ground? (Fig.31)

Figure 31 – Satellite view of the Round Barrow and possible map locations

What is even more interesting are the locations of these Round Barrows to the ancient shorelines of the dry river valley showing this to be a site of prehistoric interest as to the south of the 1800 OS map (fig. 29) is a line of large stones – were these standing stones?

What is quite clear the builders either twisted their Dyke around these features or the most likely possibility – they were built after the Dyke was constructed as it was the natural transport to these places when the waters receded in the Neolithic Period.

Figure 33 – Three Unknown Earthworks and Two Bronze Age Barrows

Further down this stretch of Wansdyke we find two further Round Barrows.

The (northern) monument includes a pair of bowl barrows aligned north east to south west and situated 150m north of the Wansdyke on All Cannings Down. They were originally part of a small group of three barrows situated close together. The exact location of the third barrow is not known. The barrow mounds have been reduced by cultivation and now form a single spread of material c.16m east-west and 14m north-south standing up to 0.2m high.

However, it is known from aerial photographs that both barrows originally had mounds measuring c.12m in diameter. These were surrounded by quarry ditches from which material was obtained during their construction. These merged together between the two mounds and will survive as buried features c.2m wide. In the late 19th century two sherds of Beaker pottery and nine sherds of Bronze Age pottery were found on the site of the barrows. These are now in the Devizes Museum. Excluded from the scheduling is the post and wire fence which runs north-south across the eastern edge of the monument, although the ground beneath is included. – Historic Britain

This (southern)monument includes a disc barrow situated on the upper north facing slopes of a prominent, wide, plateau-like ridge and immediately south of part of the Wansdyke. The barrow survives as a central circular mound of 10m in diameter and 1m high, surrounded by a 6m wide berm, with a 4.2m wide and 0.3m deep ditch and an outer bank of up to 4.5m wide and 0.7m high which is preserved differentially. To the south the ditch and outer bank are preserved as buried features, and to the north the ditch and bank have been cut by a track (not Wansdyke ditch), whilst all the remaining features are clear and intact earthworks.

Again, we see that Wansdyke kinks to either meet the Disc Barrow or that the barrows was built after its construction – proving that it was constructed by the Bronze.

Section 4 – Milk Hill (north) – Sheppard’s Shore, 3,460 metres (11,533 working days – 20 men, 1.58 years)

According to Historic England, this section – includes a Neolithic long barrow, five other linear earthwork sections crossed by or abutting the dyke and 11 Bronze Age bowl barrows adjoining Wansdyke or partially overlain by it.

The dyke includes a substantial earthwork bank that measures up to 30m wide and stands from 1m to 3m high. For the majority of its length, the bank lies south and west of a substantial open ditch. This also varies in width but measures up to 36m wide and remains open to a depth of 2m in places. The majority of the bank and ditch sections in this area together measure from 30m to 40m across.

There are six further bowl barrows along the length of Wansdyke from East of The Firs to the eastern side of Tan Hill, which are partially overlain by the dyke. These barrows vary from 10m to 20m in diameter and stand up to 3m high. Several barrows near Old Shepherds’ Shore were partially excavated in the 1850s, and finds included burnt animal and human bone and fragments of Bronze Age pottery.

As we go further down this road, more feature answers some of our questions.

Figure 34 – Wansdyke splits to meet paleochannels and gains a facility?

Fig.34 resolves most of the conjecture on what Dykes are for and why they were constructed. The Dyke now splits north and south – but why?

If it was a boundary marker, what is it marking out? If it is defensive, why stop just a few metres heading BOTH ways – what are you defending??

The picture shows a satellite picture during a dry period in this area – consequently, the paleochannels (ancient water channels that are normally unseen in the ground are very visible. Remarkably what we see is that the ditches of Wansdyke meet up with these channels and shows Wansdyke had a junction where boats could leave and join.

The deep cuts to the south (not considered to be part of Wansdyke are ancient and are currently used as footpaths. Moreover, another large ditch (not on the Historic England schedule) disappears into the old Paleochannel river (Fig. 35)

Figure 35 – Map showing the deep ditches now paths and a massive ditch going from Wansdyke

Figure 36 – Ditch on OS Map (fig.35) heading for the paleochannel – reverse view

Moreover, this ditch enters not only a watery Paleochannel but also a source of massive Sarsens Stones (Fig.37). The old OS maps show that once these stone was abundant in the local Paleochannels from the last Ice Age – the easiest way to transport them would be by boat via Wansdyke?

Figure 37 – 1800 map showing Sarsen Stones in the dry river valley next to the ditch connecting it to Wansdyke

A small dyke appears strange coming off Wansdyke a couple of hundred metres later.

| Figure 38 – Small dyke off Wansdyke – which is far more complex than the OS map or Historic Monuments have to date discovered . |

Another ditch feature that joins Wansdyke at Tanhill.

| Figure 39 – Tanhill Fair – complex earthworks |

What we see here a very complex series of ditches that join Wansdyke and go down into the Dry River Valley. This looks like a major terminal for Wansdyke and a possible trading site with Ditches allowing boats to moor.

Moreover, historically (Aubrey recorded that in the 17th century, the fair was held “within an old camp”), this has been a trading side since Medieval times and had its own white horse.

| Figure 40 – Tanhill Fair showing a supplementary ditch that connects to Wansdyke in two places and goes down into the river valley |

This picture shows the extent of the ditch works at Tanhill Fair; not only does it go much further in both directions than the Historic Monument scheduled monument register suggests, but it connects in two places to Wansdyke and a further cut to the top of the old Tanhill Fair site.

Again, this shows that Wansdyke was not defensive or a marker in the landscape as this feature (which as it connects to the main dyke) not recognised as part of Wansdyke, but clearly is contemporary and can only be for the transportation of boats via a canal.

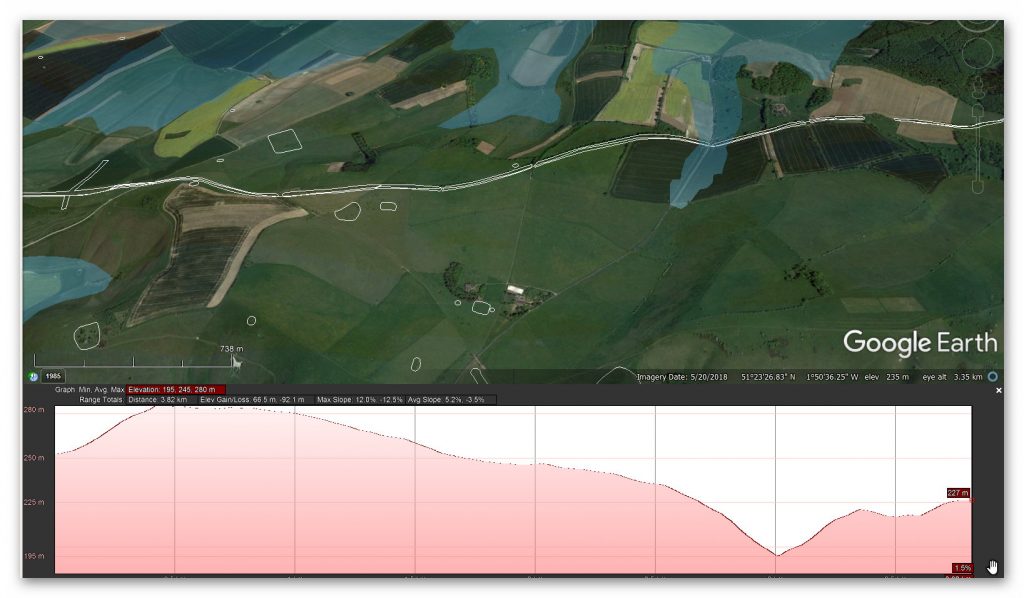

Section 5 – Sheppard’s Shore – Morgan’s Hill, 5,290 metres (17,633 working days – 20 men, 2.41 years)

| Figure 41 – Section 4 profile |

Morgan Hill Kink

| Figure 42 – Morgan Hill East ‘kink’ |

To the East of Morgan Hill is found a bizarre Kink in Wansdyke. This is best seen on an OS map which shows not only this strange direction but the obstacles it avoided.

Figure 43 – Morgan Hill East – Kink

From the topology of the hill – there is no reason to ‘Kink’ to the right, then take a tight 90-degree turn to the left – then left again (rather than continuing), then right turn to get back in line again?

This discounts the fortification idea as it goes downhill, making it lower from its height advantage and then takes two turnings (and a hell more work) to get back online – almost 100% more time and effort. This obvious also excludes it as a marker for the same construction time and resource reasons.

Moreover, again it does help us date this feature as Round barrows are surrounding this kink on both sides. So, are we saying that the builders (if it younger than the Bronze Age) went around the Barrows rather than over them?

Or is it now clear that the Barrows we created at a later date to match the contours of the Dyke?

Branch off Wansdyke

Missing off all OS maps at the top of Morgan Hill is a branch going North and down to the Mesolithic Rivers of prehistory. This feature is captured by Historic England: Cross ridge dyke on Morgan’s Hill –

The monument includes a 560m long section of a cross ridge dyke situated on Morgan’s Hill. The dyke runs from NNW to SSE across the east-west aligned ridge, dividing Morgan’s Hill into two parts. The dyke has a bank c.8m wide and up to 1.5m high. To the East of the bank lies an 8m wide ditch which provided material for its construction and enhanced the effectiveness of the boundary.

This has been partly infilled by cultivation but is open to a depth of 0.3m in places, and is visible on aerial photographs. The bank and ditch are interrupted by a number of openings through which animals and people could pass. It is not clear how many of these are original.

A further section of the dyke, situated to the south is crossed by the Wansdyke which is later in date. This further section is the subject of a separate scheduling. Excluded from the scheduling are the post and wire fences which cross it and run along its length, although the ground beneath is included.

| Figure 44 – Branch off Wansdyke |

| Figure 45 – Morgan’s Hill West with another Branch and where stukeleys drawing was taken (Fig. 12) |

Both have a bank and ditch and meet on top of Morgan’s Hill – they are one of the same but probably made at a different date. Interestingly, a paleochannel cuts through the Dyke, and that part is missing showing that this section of the Dyke is ancient (Early Mesolithic?)

East Wansdyke was built across chalk, yet excavations suggest that the builders kept the turf taken during the digging of the ditch to one side and used it to cover the bank; this stabilised the bank but also meant that it did not stand out as a white line across the green downland (Green 1971 87 32-33) and yet more reasons for this not to be either a boundary marker or defensive ditch.

If we look north from Morgan’s Hill (Fig. 45), we can see in the landscape features from satellites that Wansdyke turned north and followed the Roman Road and was met by another ditch from the main Wansdyke canal. This confirmed by the presence of Round Barrows to the right and by the raised river shorelines (top of picture), which the Roman used as an existing platform bank for their road so time later.

Figure 46 – Two more junctions off Wansdyke heading north past round barrows

West Wansdyke

We have a problem with West Wansdyke – it’s not part of East Wansdyke. This has always been a historical debate over the last 100 years. If we look at the limited archaeological evidence, then we find that although it may have been a much later canal/Dyke it is not contemporary with the East Wansdyke canal and was not built at the same time.

| Figure 47 – Dyke Feature as shown in Table |

Excavations conclusively show that the Ditches on the East side of Wansdyke are much deeper and twice as wide. In contrast, the Banks on the East Side are much wider. What I think we see here is that East Dyke was clearly built first, as our River Height model shows that most of West Wansdyke would have been flooded or marshland at the time of use.

When the waters receded, it is possible that the Dyke was extended or the more probable event of East Wansdyke after it dried up was turned into a roadway and what we see in West Wansdyke is the extension of the roadway, and hence it is wider than in the East.

We also see more shallow ditches as they were not used for water but to obtain soil for the walkway and become a drainage ditch.

Certainly, we know this was used by the Romans as a road, and they always had drainage ditches, usually on both sides. This is support by carbon dating at Erskine’s excavation at Blackrock Lane, where the section appeared to have been sealed by the primary bank material. One of these layers contained significant concentrations of woody oak charcoal.

Samples of this material were submitted to the Ancient Monuments Laboratory for radiocarbon dating in order to provide a possible construction of the bank. As shown in the table below – sadly as normal when scientific evidence disproves the current archaeological narrative – it is ignored and classified as an error.

| Figure 48 – Wansdyke West – showing it to be Prehistoric |

The other missing aspects are shown in East Wansdyke and not West Wansdyke was the massive connection to Barrows and Flint Pits. This connection is not seen on West Wansdyke, which again may help date this monument as the barrows were of Bronze age or earlier and as we have seen from the carbon dating evidence at Blackrock Lane much earlier than its 1500 BCE date.

This was an extracts from the NEW Book Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke available on Amazon as a FULL COLOUR HARD BACK (£19.95) or a ECONOMY (£4.99) SOFTBACK black and white VERSION – it is also available as a KINDLE (£1.99) book. For further information about our work on Prehistoric Britain visit our WEBSITE or VIDEO CHANNEL.

Product details

- ASIN : B0BF31GQKC

- Publisher : Independently published (18 Sept. 2022)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 134 pages

- ISBN-13 : 979-8353488897

- Dimensions : 15.24 x 1.3 x 22.86 cm

- Illustrations: 85

- Customer reviews: 5.0 out of 5 stars 1 rating

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE or on our PRESS RELEASE PAGE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.

More information is available from our website or our video channel