The Bluestone Enigma

Contents

Introduction

The Bluestone quarry sites give us complelling evidence of the Mesolithic construction dates of Stonehenge (The Bluestone Enigma)

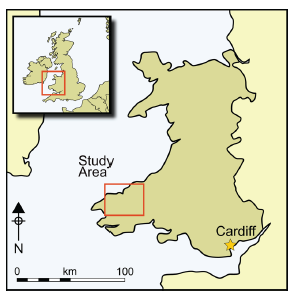

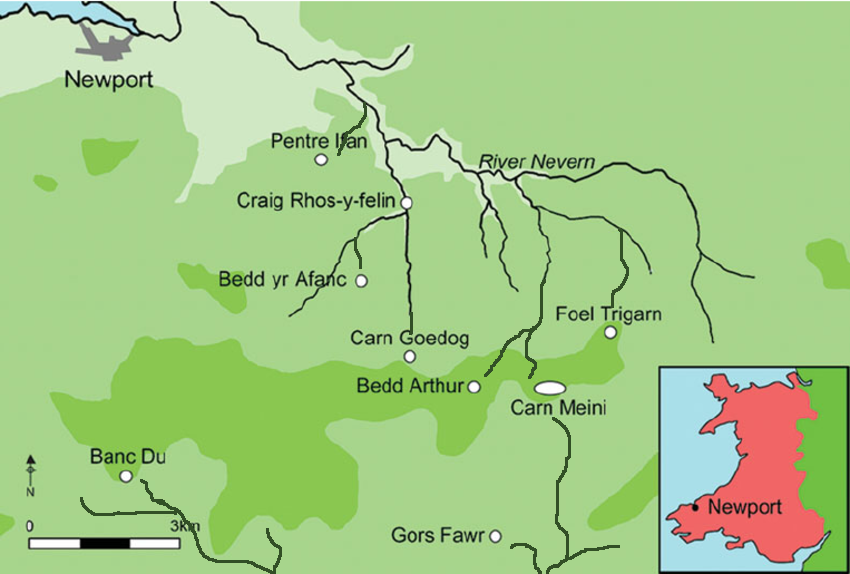

The papers published by researchers from the University of London, Southampton, and Manchester, including Mike Parker-Pearson and his team, regarding the discovery of the quarries at Craig Rhos-y-Felinand the bluestone megaliths at Carn Goedog have been a significant contribution to our understanding of Stonehenge’s origins. This research brought to light the fascinating theory that Stonehenge was initially constructed in Wales and then transported to Salisbury Plain around 500 years later.

This groundbreaking discovery not only captured the attention of archaeologists worldwide but also challenged previous assumptions about the methods and motivations behind the construction of Stonehenge. The idea that these bluestones were quarried and shaped in Wales before making their journey to Salisbury Plain adds a new dimension to our understanding of prehistoric peoples’ capabilities and social organization.

This revelation suggests a remarkable level of dedication and coordination among ancient communities. The logistical feat of transporting these massive stones over such a distance, and the decision to do so centuries after their initial quarrying, hints at the profound significance these stones—and the monument they came to form—held for the people of the time.

As someone deeply interested in the mysteries of ancient civilisations, I find the implications of this research thrilling. It deepens our appreciation for the ingenuity and spiritual dedication of our ancestors and opens up new avenues for exploring the cultural and religious ties that connected different regions of prehistoric Britain.

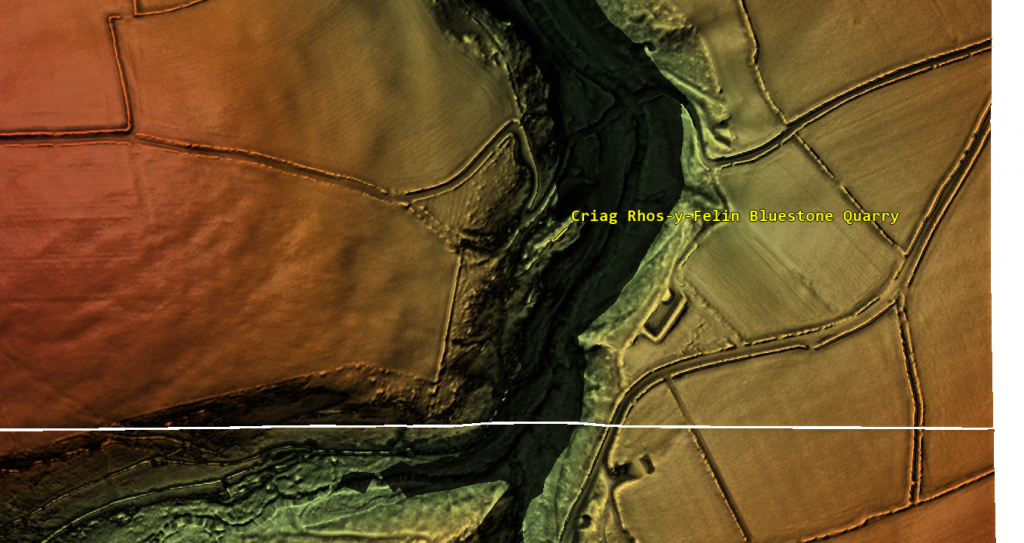

Craig Rhos-Y-Felin

The publication of the report “Craig Rhos-y-Felin: a Welsh bluestone megalith quarry for Stonehenge” in the December 2016 edition of Antiquity Magazine unveiled intriguing findings about the origins of the bluestones used in Stonehenge. This study, which identified a 4m long monolith at Craig Rhos-y-Felin as microscopically identical to the bluestones at Stonehenge, has sparked significant debate and speculation within the archaeological community and beyond.

Despite the excitement generated by these findings, the report’s focus on two radiocarbon dates that align with the authors’ hypothesis on Stonehenge’s construction date has raised questions about the completeness of the narrative presented to the public. The discrepancy between these dates and the hoped-for evidence led to the speculative suggestion that Stonehenge was initially constructed in Wales and relocated to Salisbury Plain centuries later. This narrative, while intriguing, illustrates the complexities and challenges of interpreting archaeological data and the temptation to fit new evidence into pre-existing hypotheses.

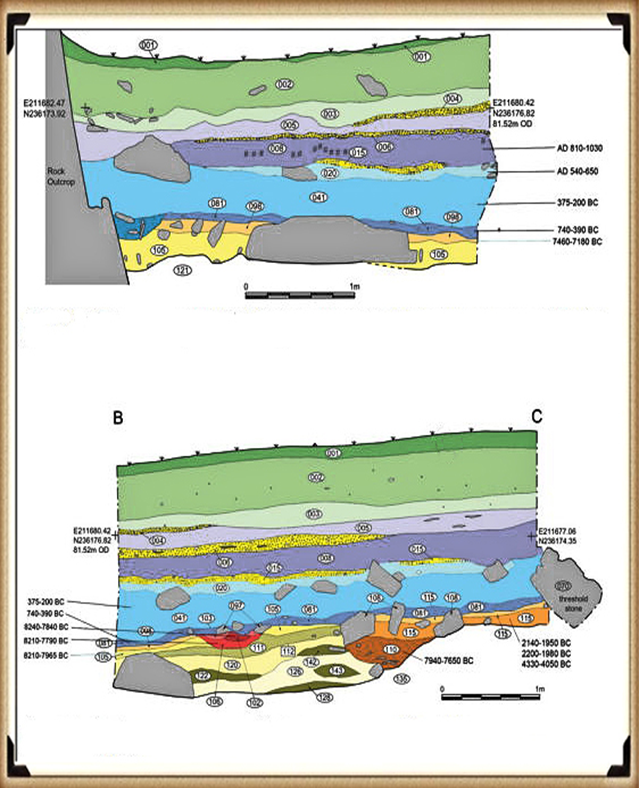

However, a more detailed analysis of the report reveals a wealth of Mesolithic carbon dates obtained from human-made hearths, suggesting a much earlier period of human activity at the site than the two Neolithic dates highlighted. These Mesolithic dates, which significantly predate the construction of Stonehenge as currently understood, were largely overlooked in the public dissemination of the research findings.

This oversight raises essential questions about the narrative surrounding Stonehenge’s origins and the methodologies used in archaeological dating. The presence of Mesolithic hearths at Craig Rhos-y-Felin suggests that the site was of importance to human communities thousands of years before the Neolithic period. This evidence challenges the conventional timeline of Stonehenge’s construction and suggests a longer, more complex history of human interaction with the landscape and the bluestones.

Furthermore, the report inadvertently highlights the ongoing debate within archaeology about how best to interpret and present findings to the public. The focus on headline-grabbing narratives, such as the relocation of Stonehenge from Wales, can sometimes overshadow equally significant but less sensational discoveries, such as the evidence of Mesolithic activity at the quarry site.

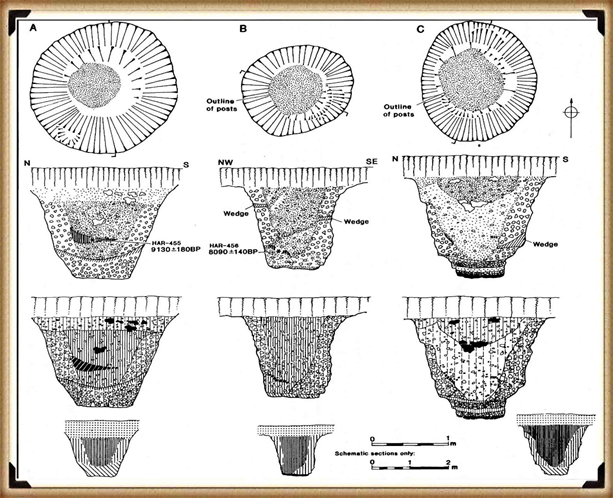

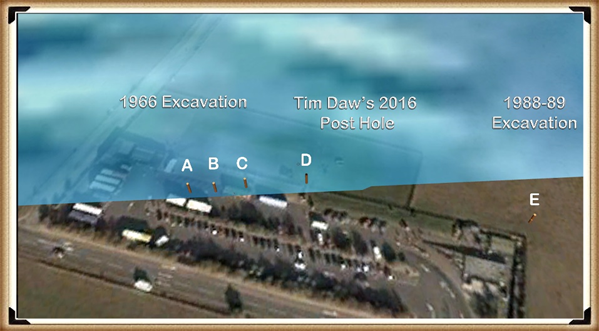

The excavation in 1966 and subsequent discoveries surrounding Stonehenge offer a fascinating and somewhat contentious glimpse into the complex task of accurately dating ancient sites. The initial observations by Lance and Faith Vatcher highlighted the Neolithic character of three holes excavated near Stonehenge, with no datable pottery found. Yet, the characteristics of the holes suggested a Neolithic origin. This assumption was later questioned when a PhD student discovered that the charcoal deposits from these holes, surprisingly composed mostly of pine, could not be Neolithic as initially thought. Pine was believed to be ‘extinct’ in the area by the time of Stonehenge’s supposed construction, according to pollen analysis.

This revelation was startling, especially to the Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission officials, later known as English Heritage. The carbon dating of these pine samples placed them squarely in the Mesolithic era, specifically between 8860 to 6590 BCE, challenging the previously accepted timeline for Stonehenge’s construction. Furthermore, the report mentions pine samples from Woodhenge, which, if also Mesolithic, would radically alter our understanding of that site’s age.

Stonehenge Car Park

Instead of seizing this opportunity to delve deeper into these findings, a narrative was constructed dismissing these posts as totem poles from wandering hunter-gatherers unrelated to Stonehenge. This decision to sideline potentially groundbreaking evidence highlights a reluctance within some parts of the archaeological community to reconsider established narratives, even in the face of new evidence.

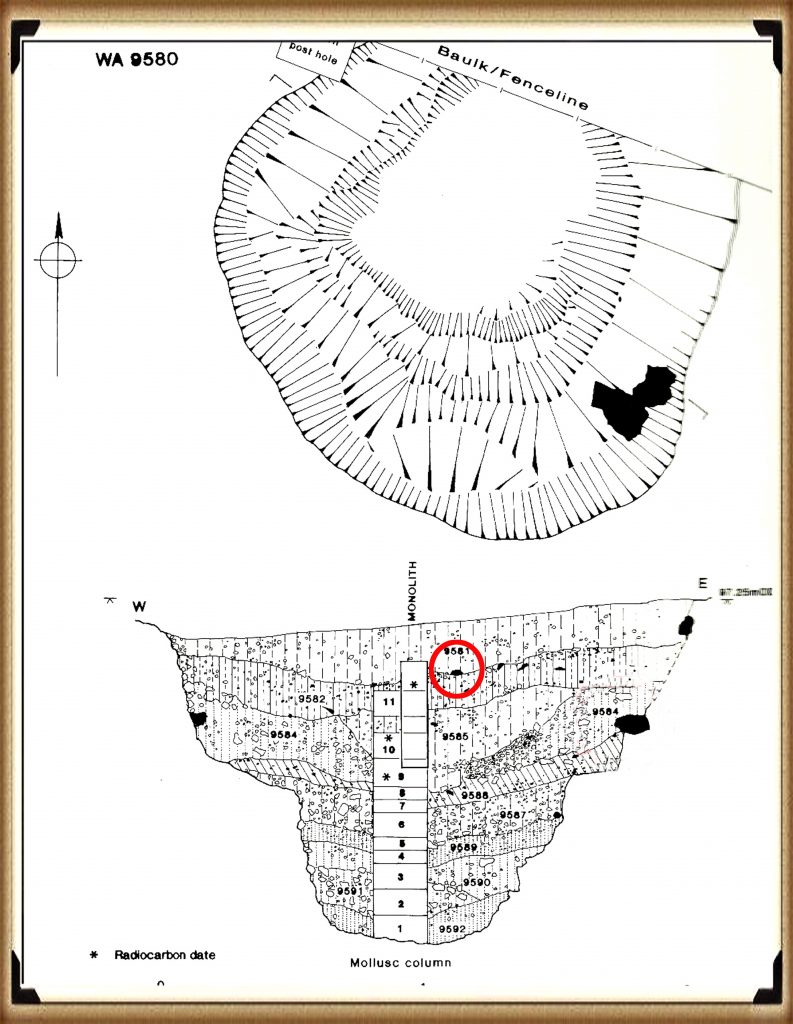

The discovery in 1988-89 by Wessex Archaeology of another Mesolithic post hole, along with a piece of rhyolite dated to 7737 – 7454 BCE, further complicates the timeline for Stonehenge and the surrounding area. This finding should have prompted a reevaluation of the site’s dating. However, attempts to fit this new evidence into the existing narrative of Stonehenge’s construction timeline illustrate the challenges and controversies inherent in archaeological interpretation.

These instances underscore the necessity for openness, curiosity, and a willingness to revise our understanding of history in light of new evidence. They remind us that the story of human history is complex and continually evolving, and our interpretations must adapt as we uncover more about our past.

Discoveries at Stonehenge, including charcoal (OxA-18655) found in the Hole socket of Stone 10, dating back to 7330 – 7060 BCE, match the Mesolithic post holes’ dates, presenting significant implications for our understanding of the site’s history. This evidence, aligning with the era of the Mesolithic post holes, suggests that the activities at Stonehenge and its surroundings span back to much earlier than previously believed. However, the apparent suppression of this news from widespread media attention raises questions about the narrative being presented to the public and within educational materials.

The excavation at Blick Mead, less than a mile away from Stonehenge, by the Open University, which uncovered evidence of Mesolithic period habitation and feasting, further challenges the entrenched views held by some about prehistoric life around Stonehenge. These findings suggest a continuous and significant presence of people in this area during the Mesolithic period, contradicting the simplistic ‘totem pole’ myth still perpetuated in some narratives by English Heritage (EH) through their exhibitions and guidebooks.

Moreover, the recent transformation of the Stonehenge site, including the closure of the B-road past the stones and the relocation of the visitor’s car park to a new, multi-million-pound visitor centre, represents a significant shift in how the site is accessed and experienced by the public. The removal of the old tarmac and the reversion of the land to grass aim to restore a more authentic prehistoric ambiance to Stonehenge. This effort to make the site appear more as it did at the time of its construction is commendable but also highlights the ongoing tension between modern interpretations of the site and the emerging evidence of its ancient past.

These developments at Stonehenge and Blick Mead exemplify the dynamic nature of archaeological research and the complexities involved in interpreting and presenting the past. As new evidence continues to emerge, the narrative of prehistoric Britain needs to evolve accordingly, ensuring a more accurate and nuanced understanding of these ancient landscapes and their significance to human history.

You would indeed think that removing the tarmac from the old visitor’s car park at Stonehenge, especially given the previous significant findings beneath it, would prompt a comprehensive excavation to unearth more evidence about the site’s Mesolithic history. Such an excavation could potentially transform our understanding of Stonehenge and its origins, providing invaluable insights into its early history and the people who frequented the site during the Mesolithic period.

Tim Daw’s role as a warden at Stonehenge, combined with his proactive approach to documenting changes and features of the site through photography, exemplifies the kind of engaged observation that can lead to important discoveries. His finding of patch marks by the central upright stones, indicating the possible positions of missing stones from the Inner Circle, is a testament to the contributions individuals can make to the ongoing investigation of Stonehenge. Daw’s work underscores the value of continuous and attentive observation of archaeological sites, even by those not formally conducting research.

The discovery of such featuresand the potential for further findings beneath the former car park area highlights the need for a thorough and systematic archaeological examination whenever opportunities arise. These efforts not only enrich our knowledge of Stonehenge’s past but also contribute to the broader understanding of prehistoric human activity in the region. As we continue to peel back the layers of Stonehenge’s history, each finding adds a piece to the puzzle of this enigmatic monument’s story, emphasizing the importance of preserving and exploring our archaeological heritage.

Tim Daw’s experiences and observations as a warden at Stonehenge, particularly regarding his discovery of additional post holes beneath the old visitor’s car park, spotlight the continuous potential for new findings that can challenge and enrich our understanding of Stonehenge’s history. Despite being warned against publishing his conclusions due to unauthorised blog activities, Daw chose to resign and continue his work, revealing through ‘unofficial’ pictures the existence of even more post holes under the car park, aligned with those discovered in 1966.

Bluestone Quarries

These findings, including the newly discovered post hole that aligns with the four others from 1966, support the hypothesis that these structures are situated on what was once the shoreline of the River Avon around 8000 BCE. This suggests that during the Mesolithic period, the stones quarried in Wales could have been transported via boat directly to Stonehenge, navigating through enlarged rivers rather than taking a longer sea route proposed by some archaeologists.

Further complicating the narrative are my analyses of the bluestone structures from other Preseli sites like Carn Goedog and Craig Talfynyydd, which are connected by streams and rivers to the River Nevern. Unfortunately, archaeologists have interpreted this network of waterways primarily through a religious lens rather than considering its practical functionality for transportation.

The persistence of the ‘ox-cart’ route theory, which proposes a land path following the modern A40, overlooks the logistical challenges posed by the period’s dense woods, swamps, and forests. Such conditions would have made the construction and use of a road system highly impractical, if not impossible.

My critique extends to the inconsistencies and logical inaccuracies within the archaeological narrative, especially concerning the site layout and geological evidence at Craig Rhos-y-Felin. The assumption that floodwaters in the area were solely the result of ice melt, quickly draining into the sea post-Ice Age, ignores the broader implications of such flooding for the landscape and its inhabitants.

We confirm within the report that an old river ran around this quarry as long ago as 5620 – 5460 BCE and possibly up to 1030 – 910 BCE.

“Most of the site was then covered by a layer of yellow colluvium (035), dated by oak charcoal to 1030–910 cal BC (combine SUERC-46199; 2799±30 BP and SUERC-46203; 2841±28 BP). This deposit is contemporary with the uppermost fill of a palaeochannel of the Brynberian stream that flowed past the northern tip of the outcrop. Charcoal of Corylus and Tilia from the basal fill of this palaeochannel dates to 5800–5640 cal BC (OxA- 32021; 6833±40 BP) and 5620–5460 cal BC (OxA-32022; 6543±37 BP), both at 95.4% probability.”

The report’s insights suggest that during the Mesolithic Period, an enlarged stream feeding into the River Nevern reached up to the quarry outcrop rocks. Notably, it was positioned just a few meters away even up until 1000 BCE. This geographical configuration implies that boats were likely the primary mode of transport for the large, newly quarried stones to their final destination at Stonehenge, mirroring stone transportation methods seen in other ancient civilizations, such as Egypt.

The site layout at the quarry provides crucial clues about the timing of the stone quarrying. Notably, a single monolith is positioned near the river on the site’s east side, ready for transportation. Nearby, to the south of this monolith, are human-made hearths, precisely where one would expect them to be. However, the challenge arises with the dating of these hearths as Mesolithic, with three distinct periods identified: 8550 – 8330 BCE; 8220 – 7790 BCE; and 7490 – 7190 BCE. Despite this, the report asserts that there is no evidence of Mesolithic quarrying or working of rhyolite at this site.

This claim overlooks the practical use of tools across different periods. If Mesolithic and Neolithic communities utilised similar tools, distinguishing tool marks from these different periods might be more challenging than the report suggests. Moreover, the presence of these communities at the quarry for over a millennium raises questions about their activities if not quarrying the stones.

The connection between the quarry site and Stonehenge is strengthened by over twenty Carbon-14 dates that align with my hypothesis, in contrast to the mere two samples currently highlighted by experts, dated 300 – 500 years older than existing estimations. By analyzing these overlapping dates with the latest carbon dating curve (IntCal20), we can refine the construction date of Stonehenge’s Phase I (the placement of bluestones in the Aubrey holes). By calculating the mean average of these probable dates, we aim to achieve a more accurate estimation of when this monumental task was undertaken, potentially rewriting the timeline of one of the world’s most enigmatic prehistoric monuments.

Carbon Dating

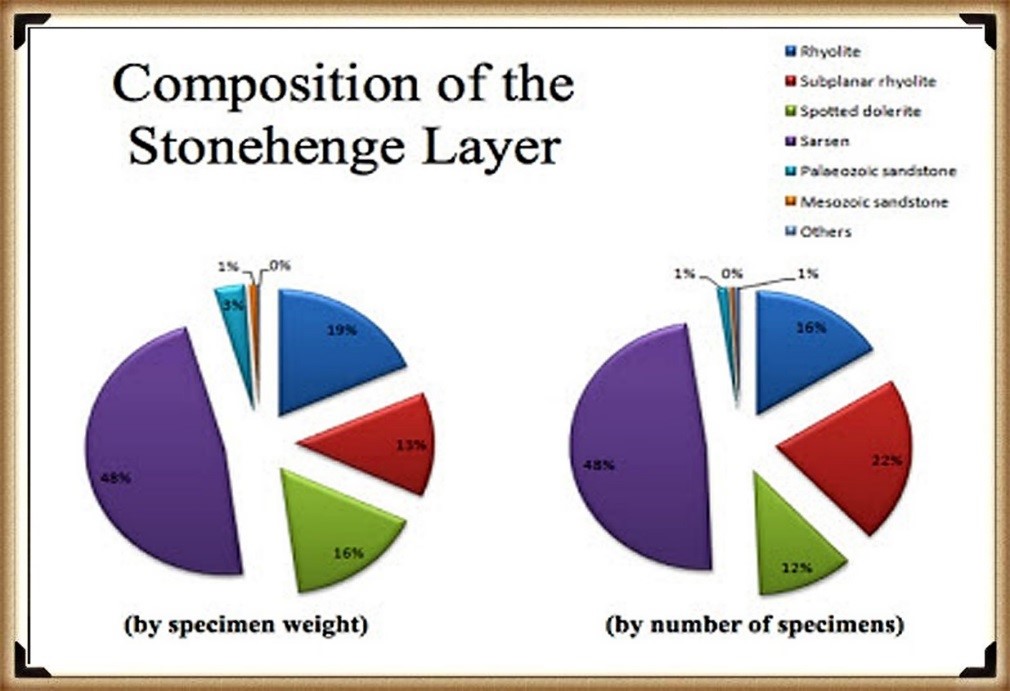

| Stonehenge | Old Car Park (Ref. and Date) | Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Ref | Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Dates | Carn Goedog Ref & Dates |

| Post Hole A | HAR-455 (8825 – 7742) | SUERC-50761 OxA-30507 OxA- 305481 SUERC-51164 SUERC-50760 OxA-30549 SUERC-51165 OxA-30506 OxA-305482 OxA-305062 OxA-30547 OxA-30504 | 8550 – 8330 8471 – 8285 8286 – 8163 8289 – 8169 8211 – 7955 8238 – 7941 8216 – 7785 8021 – 7792 8122 – 7962 8207 – 8030 8012 – 7711 8281 – 8166 | |

| Post Hole B | HAR–456 (7377 – 6651) | OxA-305032 | 7232 – 7188 | OxA31823 – 7190 to 6840 |

| WA 9580 | GU-5109 (8259 – 7742) | OxA- 30548 SUERC-51164 SUERC-50760 OxA-30549 SUERC-51165 OxA-30506 OxA-305482 OxA-305062 OxA-30547 OxA-30504 | 8286 – 8163 8289 – 8169 8211 – 7955 8238 – 7941 8216 – 7785 8021 – 7792 8122 – 7962 8207 – 8030 8012 – 7711 8281 – 8166 | |

| WA 9580 | QxA-4219 (7737 – 7454) | Beta-392850 OxA-30547 | 7944 – 7648 8012 – 7711 | OxA-35184 – 7590 to 7380 |

| WA 9580 | QxA-4220 (7595 – 7178) | SUERC-51163 OxA-30523 OxA-3050311 | 7539 – 7308 7472 – 7182 7485 – 7248 |

Table 1– Matching Carbon Dates

The calculations indicate that work at the quarry began around 8300 BCE, with its main phase of activity around 8000 BCE, and continued for at least a millennium, challenging the conventional narrative about Stonehenge and its Bluestones. This timeline suggests a far more ancient and enduring connection between the quarry site and Stonehenge than previously acknowledged.

Carn Goedog

Initially, Carn Menyn in the Preseli Hills was believed to be the source of Stonehenge’s spotted dolerite, but later analysis pinpointed Carn Goedog as a closer chemical match. Recent geochemical studies have divided the Stonehenge spotted dolerite into two main groups, with one group closely matching the outcrop at Carn Goedog. The origin of the second group remains uncertain, potentially deriving from Carn Goedog or nearby outcrops.

Further geological investigations at Stonehenge have identified additional sources for its bluestones. Unspotted dolerite matches with outcrops at Cerrigmarchogion and Craig Talfynydd on the Preseli ridge. Another bluestone variety, “rhyolite with fabric,” traces back to Craig Rhos-y-Felin, while a source of Lower Palaeozoic sandstone has been identified north of the Preseli hills. The origin of volcanic tuffs found at Stonehenge also likely lies in the Preseli area.

Surface indications of post-medieval Quarrying, particularly on its south side, have evidenced Carn Goedog’s accessibility. This historical quarrying, distinguishable by cylindrical drill holes on some quarried blocks at the outcrop’s base, was performed using the ‘plug-and-feather’ technique with metal wedges. The discovery of a worn trade token under one of these blocks helps date this activity to around the year 1800.

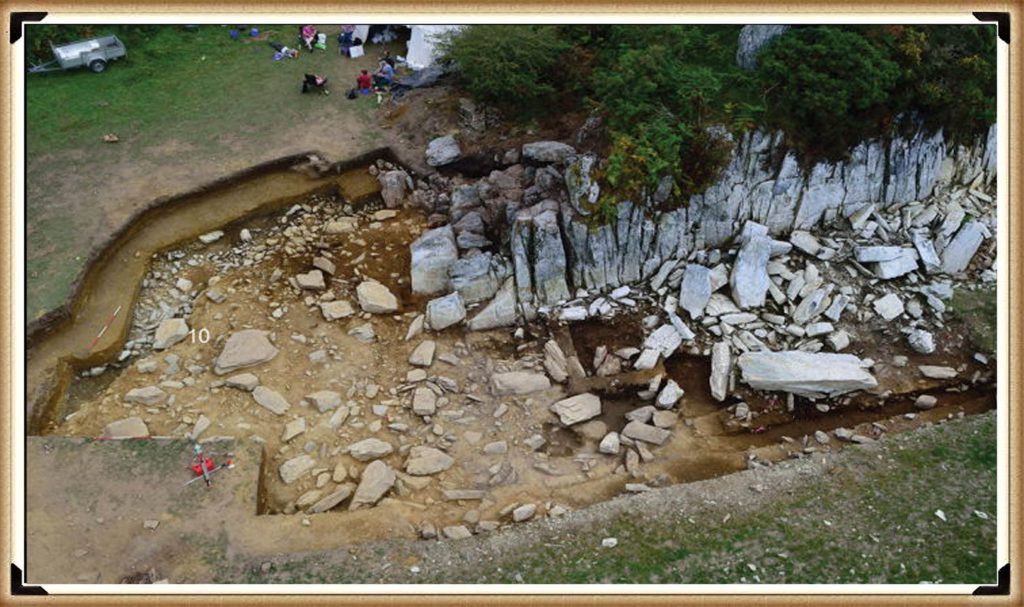

In 2014, test trenching along the southern edge of Carn Goedog unveiled layers of human activity spanning various periods, from the recent centuries found in trench 3 to deeper layers of prehistory identified in trench 2. Trench 1, strategically positioned at the outcrop’s base and just beyond the eastern limit of the early modern quarry debris, was particularly significant. It was seen as offering a unique opportunity to uncover evidence of prehistoric quarrying that hadn’t been disturbed by later activities.

This layered historical context at Carn Goedog is crucial for understanding the complex human interactions with the site over millennia. The evidence for prehistoric quarrying, undisturbed by the later post-medieval activity, provides invaluable insights into the methods and technologies used by ancient peoples to extract and transport the stones that would contribute to the construction of monumental structures like Stonehenge.

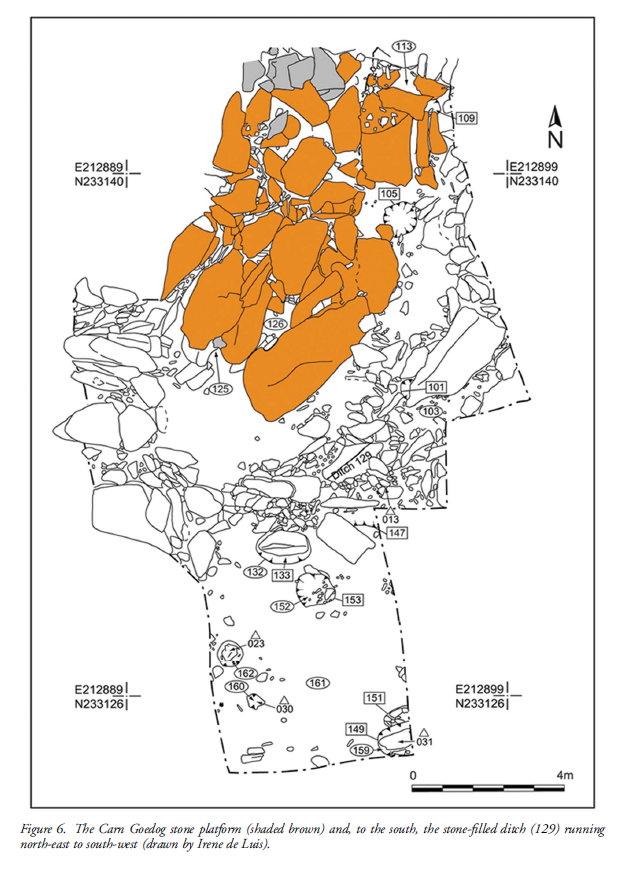

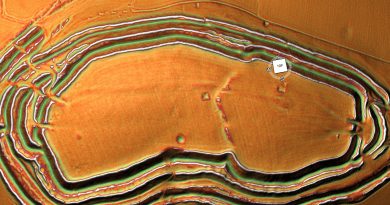

Trench 1 was enlarged in 2015 and 2016 to reveal features that may relate to prehistoric quarrying activity. At the southern foot of the outcrop, excavation revealed an artificial platform of flat slabs—many of them split—laid (with the split faces upwards) in a tongue-shaped formation 10m north–south by at least 8m east–west (Figure 6).

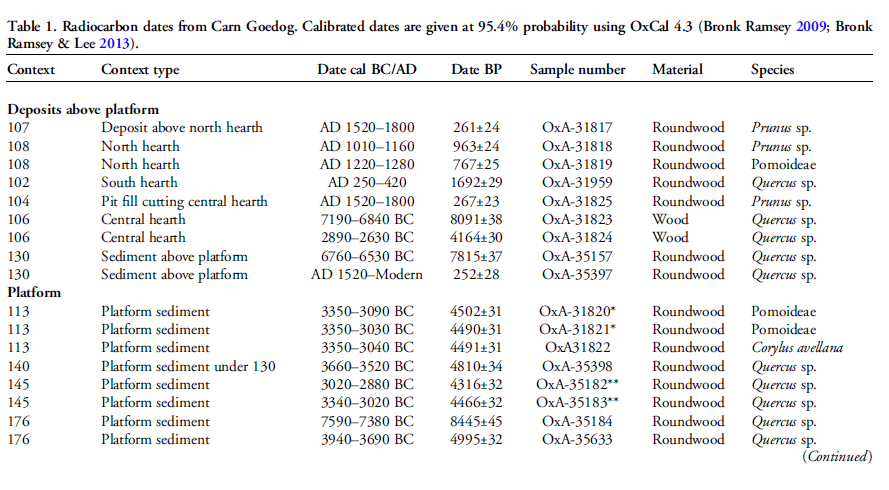

Those slabs lying against the face of the outcrop had been pressed into the underlying sediments, presumably by the weight of pillars lowered onto the platform. The platform terminates from the outcrop with a vertical drop of 0.9m to the ground surface beyond. This platform is stratigraphically earlier than a series of deposits that included early modern quarrying debris and hearths of the Roman and medieval periods. One hearth (Figure 6: 105) set within a gap in the platform where a slab had been removed produced charcoal dating to 7190–6840 cal BC (8091±38 BP) and 2890–2630 cal BC (4164±30 BP) (Table 1).

The findings across the quarry sites, including Carn Goedog and Craig Rhos-y-Felin, point to a nuanced understanding of how the bluestones were utilised and replenished at Stonehenge. The hearths discovered at these sites, particularly those dating to the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, suggest ongoing human activity and potentially organised efforts to quarry and transport bluestones over extended periods. This insight challenges the conventional explanation that the transportation of Bluestones to Stonehenge was a singular event.

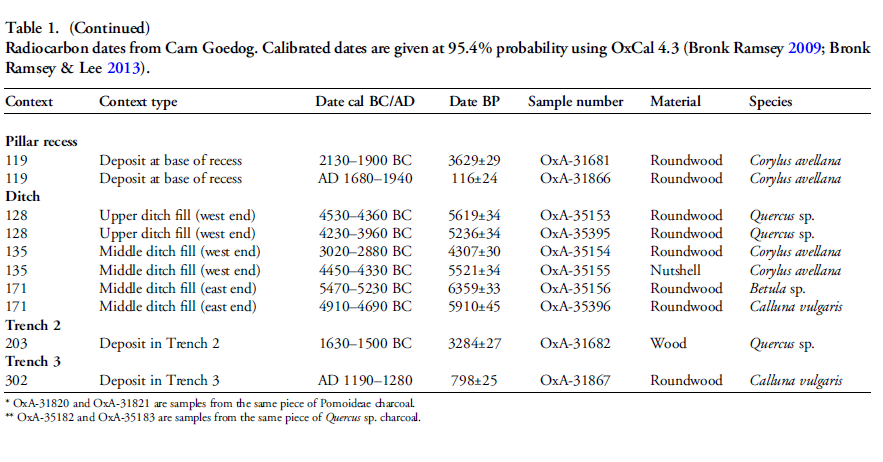

The Stonehenge Layer

The evidence of modern quarrying at both the northern and southern ends of these sites and the dates from central hearths aligns with observations made at Craig Rhos-y-felin. Our research, as outlined in published books, supports the theory that ancestors engaged in the chipping away of bluestones at Stonehenge for healing as they utilised the water in the ditch to bathe their sickness away, as evidenced by the ‘Stonehenge Layer’ discovered by Dervill and Wainwright in 2008. This practice would naturally lead to the depletion of bluestones over time, necessitating periodic replenishment from the quarries.

The conventional narrative, which posits that the bluestones were transported to Stonehenge in a one-off event, needs to account for the scientific data emerging from these quarry sites and the Stonehenge site. The evidence suggests a more complex interaction with these stones, involving repeated quarrying and transportation activities that likely spanned centuries. This ongoing relationship with the bluestones reflects a deeper functional connection to these stones, underscoring the importance of revisiting and revising our understanding of Stonehenge’s construction and the role of bluestones within this prehistoric monument.

English Heritage’s significant investment in the Stonehenge Visitors Centre, including the creation of exhibitions that present established theories about the monument’s origins and functions, raises questions about the implications of discoveries that contradict these narratives. If foundational assumptions about Stonehenge are proven incorrect, it could have financial repercussions, particularly if the narrative presented to the public through expensive exhibitions becomes outdated or inaccurate. This situation underscores the complex relationship between archaeological research, public interpretation, and financial investments in heritage sites.

Further Information

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.

To understand why rivers were larger in the past we have video with all the relevant information.

The full video about Craig Rhos Y Felin

Other Posts

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Prehistoric Britain Blog Review - Prehistoric Britain