Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

Contents

Introduction

The third book in my trilogy aims to weave together the discoveries made across Britain, with a particular focus on Stonehenge, to shed light on a civilisation that archaeologists have termed the ‘megalithic builders.’ This civilisation is markedly distinct from those that came after, showcasing an extraordinary level of capability and engineering skill in moving vast stones and constructing earthworks that have endured for nearly ten thousand years. These achievements are even more striking when compared to the structures left by the Romans, who occupied these lands for hundreds of years yet left behind fewer enduring monuments. (Atlantis connection)

Video

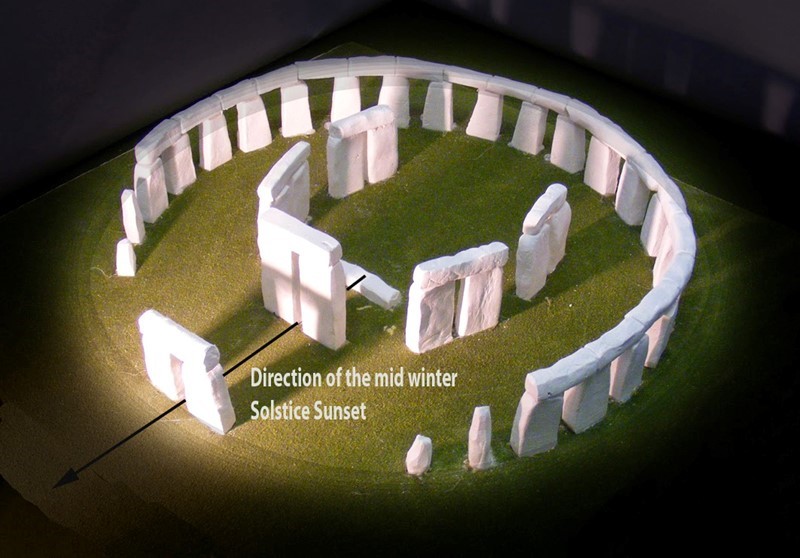

The megalithic builders’ legacy, characterised by iconic structures such as Stonehenge, reveals a sophisticated understanding of both engineering and astronomy. Their ability to align massive stones with celestial events suggests a deep connection to their environment and a complex societal organisation capable of undertaking such monumental projects. This civilisation’s accomplishments in stone construction and earthwork highlight their technical prowess and their cultural and spiritual values, as many of these sites are believed to have served practical and functional purposes.

In writing this third book, I aimed to connect the dots between various megalithic sites across Britain and explore the knowledge, skills, and motivations of the people who built them. By examining the evidence left by the megalithic builders, from the stones they transported and erected to the earthworks they shaped, we can gain insights into a civilisation that continues to fascinate and inspire despite its distance in time.

This exploration is an academic exercise and a journey into the heart of a civilisation whose creations still stand as a testament to human ingenuity and perseverance. The megalithic builders may have vanished into the mists of time, but their legacy endures, inviting us to marvel at their achievements and to contemplate our own place in the continuum of human history.

The Megalthic Builders

The megalithic builders, a fascinating civilisation from our prehistoric past, operated on a scale and with a level of cooperation that transcends modern conceptions of boundaries and nation-states. Their domain spanned northern Europe, a testament to their widespread influence and shared cultural or technological practices. Unlike the segmented and often isolated cultures that followed, these ancient builders engaged in monumental constructions that served both the living and the dead, creating long barrows and dolmens as eternal resting places and linear earthwork canals and stone trading circles for the living.

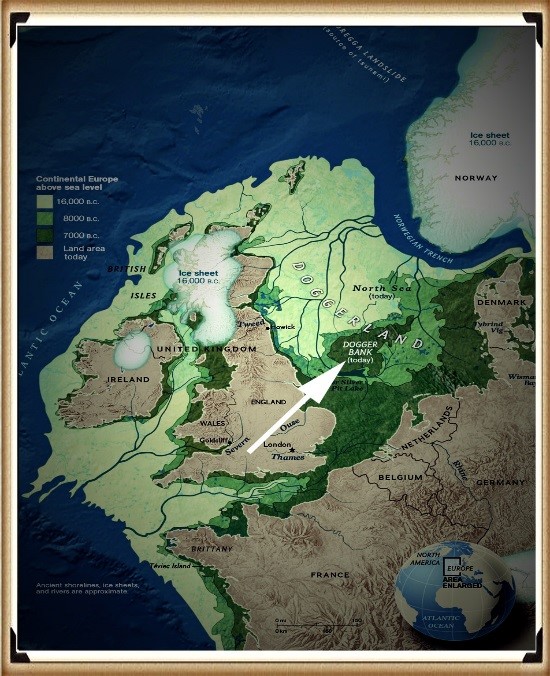

One of the most intriguing aspects of their civilisation is the central role played by an area now submerged beneath the North Sea, known as Doggerland. This now-lost land, which started to succumbed to rising sea levels approximately 9,000 years ago, was once a vital part of a massive Mesolithic landscape. Doggerland connected the British Isles to mainland Europe, serving as a crossroads for people, ideas, and goods. The remnants of this landscape, including the Dogger Bank, provide a tantalising glimpse into a world where megalithic builders thrived, interacting with their environment and each other in sophisticated ways.

The disappearance of Doggerland due to post-glacial sea level rise did not merely result in the loss of land; it marked the end of a significant chapter in human history. This transformation from a vast, interconnected landscape to a series of islands fundamentally altered the trajectory of European civilisation. The megalithic builders’ legacy, however, remains etched in the stone and earthworks that dot the landscape of northern Europe, enduring monuments to their engineering prowess and cosmopolitan outlook.

Their achievements compel us to reconsider our understanding of prehistoric societies, challenging us to appreciate the complexity and depth of human ingenuity long before the advent of written history. The megalithic builders remind us that the desire to connect, communicate, and commemorate is a fundamental aspect of the human condition, transcending time, space, and the ever-changing contours of the earth.

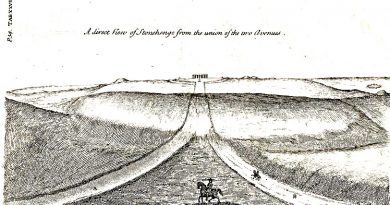

The Stonehenge Connection

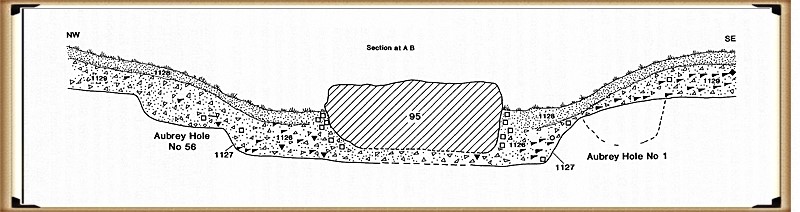

We can see from their greatest achievement, Stonehenge, a ‘message in the bottle’ the megalithic builders left us some 5,000 years ago. Although subsequent civilisations re-used and altered aspects of the Stonehenge Monument, some of the most influential aspects and stones still survive in situ due to the megalithic ability to manoeuvre vast weight, which effectively hindered lesser cultures in their attempt to alter the significance of the site radically.

The origins of the Altar Stone at Stonehenge, described by Professor Hawkins as a “fine-grained pale green sandstone” notable for its mica flakes and glitter”, have long been a subject of speculation among experts. The prevailing theories had pointed towards Wales or Devon as the stone’s source. However, recent findings challenge this perspective, suggesting the stone could have originated from much further afield, potentially from as far north as Scotland. This revelation aligns with my hypothesis, presented in my book over a decade ago, proposing an even more dramatic provenance for the Altar Stone—not just from the north, but from the northeast, specifically from the submerged landscapes of Doggerland.

Doggerland, the now-submerged landmass that once connected the British Isles to mainland Europe, represents a significant part of Mesolithic Europe’s landscape. The suggestion that the Altar Stone might have originated from this ancient and lost territory adds a fascinating layer to our understanding of Stonehenge’s construction. It implies that the builders of Stonehenge not only could transport massive stones over vast distances but also that their network of trade or cultural exchange spanned a far greater area than previously thought, encompassing regions that are now beneath the sea.

The connection between Doggerland and Stonehenge, particularly through the Altar Stone, hints at a deeply intertwined prehistoric landscape that extends beyond current geographical boundaries. The intriguing alignment from the Altar Stone towards the last vestiges of Doggerland, known as the Isle of Dogger, intersects with another enigmatic feature of Stonehenge: the Slaughter Stone. This stone, distinctively recumbent and partially buried by the surrounding ditch, has long puzzled archaeologists. Its unique position within the Stonehenge complex and the name attributed to it by the Druids suggest a significant ceremonial or symbolic role.

The deliberate placement of the Slaughter Stone, when considered in alignment with the direction pointing towards the remnants of Doggerland, could indicate a deliberate, symbolic gesture by the builders of Stonehenge, perhaps to commemorate or maintain a connection with their ancestral lands now submerged beneath the North Sea. This alignment and the specific use of stones from distant locations underscore the profound sense of purpose and meaning the Stonehenge builders invested in the site’s construction.

These potential connections to Doggerland not only expand our understanding of Stonehenge’s geographical and cultural significance but also invite us to consider the broader networks of communication, travel, and exchange that existed in prehistoric Europe. The use of stones from such distant sources and the possible alignments with lost lands hint at an intricate web of relationships and a deep historical consciousness among the people who constructed Stonehenge.

As we continue to unravel the mysteries of Stonehenge and its stones, the importance of considering wider landscapes and connections becomes clear. The potential links to Doggerland offer a tantalising glimpse into the minds of the megalithic builders, revealing a world where memory, landscape, and the movement of materials were intimately connected. These insights challenge us to look beyond the immediate vicinity of prehistoric monuments and to consider the vast, now-hidden landscapes that were once integral to the lives and beliefs of ancient peoples.

This hypothesis challenges the conventional archaeological narrative and suggests a level of sophistication and reach in prehistoric societies that is only beginning to be understood. It underscores the importance of reconsidering and expanding our investigation into the origins and connections of the materials and people involved in creating monumental structures like Stonehenge. As we continue to uncover more about these ancient builders, their methods, and their world, it becomes increasingly clear that their achievements were far more complex and interconnected than once imagined, bridging lands that are now separated by waters but were once part of a vast, interconnected landscape.

The Atlantis Connection

The completion of the quest to pinpoint the homeland of the megalithic builders marks a significant milestone in our understanding of this remarkable civilisation. The evidence of their extraordinary engineering achievements, from constructing monumental stone structures like Stonehenge to creating extensive earthworks such as Silbury Hill, underscores the sophistication and capabilities of these ancient architects and engineers. Without the modern machinery and technology, we rely on today, their achievements in construction speak to a profound understanding of their environment and a remarkable ability to manipulate natural materials to their will.

Given the scale of their constructions and the distances over which materials, such as the stones used in megaliths, were transported, it becomes clear that these builders possessed sophisticated means of transportation. The absence of roads supporting the movement of such massive stones across vast distances suggests that ships and boats were essential to their way of life. Waterways would have served as the arteries of trade, travel, and communication, connecting distant communities and facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices across Europe.

This reliance on maritime technology indicates that the megalithic builders were skilled engineers, architects, and adept sailors and navigators. Using boats would have allowed them to traverse prehistoric Europe’s coastal and riverine landscapes, enabling the widespread distribution of their megalithic culture. Such capabilities would have been crucial for orchestrating the large-scale cooperative efforts to construct the monumental stone structures that define their legacy.

The comparison with the maritime achievements of the Greeks and Romans, celebrated for their advancements in shipbuilding and navigation, underscores the significance of the megalithic builders’ accomplishments. Their ability to harness the power of water for transportation and communication is a testament to their ingenuity and a critical factor in their success as a civilisation.

The megalithic builders’ reliance on maritime technology for movement and communication across Europe highlights a sophisticated understanding of their environment and an unparalleled ability to manipulate it to their advantage. This aspect of their civilization offers valuable insights into the complexity of prehistoric societies and challenges us to expand our appreciation of their technological and cultural achievements.

Plato

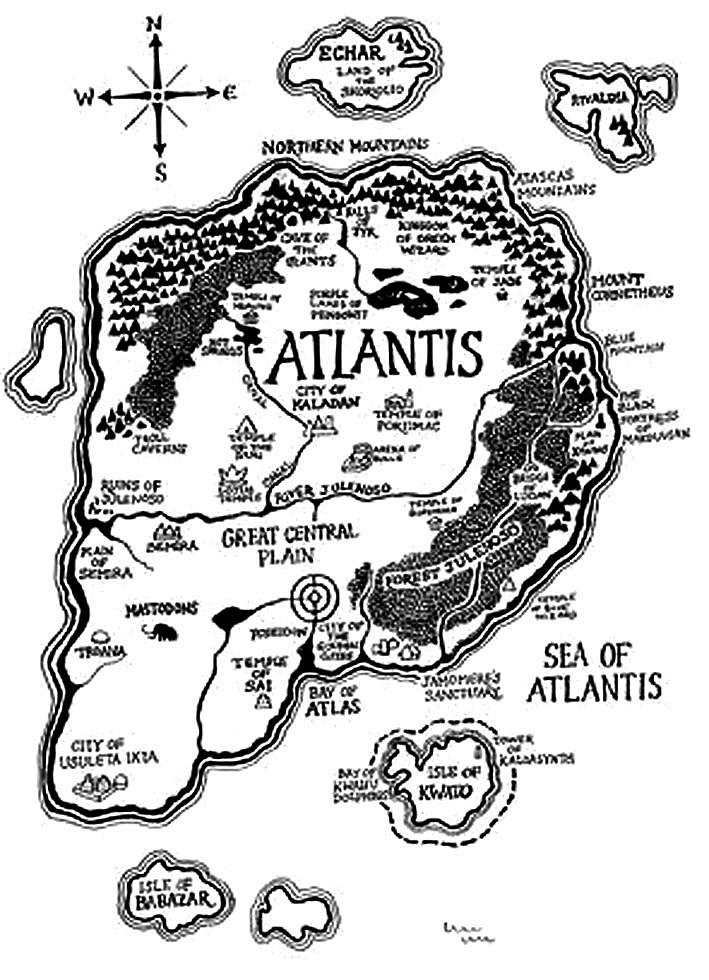

The tale of Atlantis, as relayed by Plato, stands as one of the most captivating stories from antiquity, blending the lines between historical account and mythological narrative. Over time, the story of this advanced civilisation that supposedly sank into the sea around 9,000 years ago has been transformed by modern interpretations and entertainment into something more akin to science fiction. This transformation has, unfortunately, obscured the significance of Plato’s account, relegating it to the realm of mere fantasy in the eyes of many.

Plato, a philosopher of unparalleled influence in Western thought, presented the story of Atlantis not as a myth but as a recounting of historical fact told to him by Solon, who had learned it from Egyptian priests. According to the narrative, Atlantis was a civilisation of great power and technological prowess, with ships that traversed the globe and a highly advanced society.

The comparison between the story of Atlantis and the archaeological evidence of Doggerland and the megalithic builders is striking. Like the Atlanteans, the people of Doggerland, who lived around 10,000 years ago, exhibited advanced capabilities, particularly in maritime technology. They built monumental structures and possessed the knowledge to navigate and sail to distant lands. This evidence challenges the prevailing academic view of prehistoric societies as simplistic hunter-gatherer tribes and aligns with Plato’s description of Atlantis as a great and advanced civilisation.

Moreover, the presence of notable figures such as Solon, a key figure in the development of democracy in ancient Greece, and Socrates, celebrated for his wisdom, in the dialogues discussing Atlantis, lends credibility to the account. Their involvement suggests that the story was taken seriously by some of the most respected thinkers of the time, who did not dismiss it as mere fiction.

Some academics’ reluctance to accept the possibility of advanced prehistoric civilisations is perhaps understandable, given the scarcity of direct archaeological evidence and the challenge of separating historical fact from myth. However, the megalithic stones and the submerged landscapes of Doggerland offer tangible links to a past that may have been far more complex and interconnected than previously acknowledged.

The possible connection between Doggerland, the story of Atlantis told by Plato, and the initial stages of Stonehenge’s construction around 8300 BCE raises the hypothesis that these ancient events might be related or have a common origin. The dating of Stonehenge’s beginning to such an early era matches the timeline of Plato’s Atlantean civilisation, indicating a potential connection or shared features between the Stonehenge builders and the advanced society described in the Atlantis legend.

This theory challenges commonly accepted beliefs about the achievements and timelines of prehistoric humans. It suggests that Stonehenge, a monument that has fascinated scholars and visitors for centuries, might have originated during the same period as the legendary civilisation of Atlantis. This discovery prompts a reassessment of human activities during the Mesolithic period.

It is possible to imagine a prehistoric world where societies were not only technologically advanced but also well-connected across vast distances, given the architectural complexity and navigational skills demonstrated in the stories of these civilisations. The hypothesis that the megalithic builders, who were capable of maritime travel and the construction of monumental structures like Stonehenge, might have shared a cultural or historical link with the Atlanteans, adds depth to the narrative of human history during the Mesolithic era.

This viewpoint emphasises a more inclusive and transparent approach to archaeology, emphasising the significance of sustained inquiry and the readiness to question conventional historical accounts. With the emergence of new findings that challenge long-standing assumptions, the links between Doggerland, Atlantis, and Stonehenge exemplify the intricate and multifaceted character of early human civilisation’s accomplishments.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Prehistoric Britain Blog Review - Prehistoric Britain