Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

Contents

Introduction

In the past ten years, I have faced significant challenges in establishing the validity of my claim that Linear Earthworks are prehistoric canals. Many people have dismissed my theory, but I have not let that stop me. I undertook a comprehensive survey of 1500 Historic England’s Scheduled Linear Earthworks, and the findings culminated in the first book of a quadrilogy series detailing the East Wansdyke area. This publication is a significant personal milestone and an unprecedented achievement in the field of archaeology that no university or research team has matched.

My book meticulously surveys every aspect of East Wansdyke, placing it within the context of the ‘Ancient Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke.’ I aim to challenge the existing narratives of archaeology with hard scientific evidence. The core of my book challenges the existing archaeological hypotheses surrounding Wansdyke and Linear Earthworks. I have exposed the fundamental flaws in these long-held beliefs. It’s a bold claim, but I back it with rigorous research and analysis, pushing the boundaries of what we thought we knew about these ancient structures.

The implications of my research are profound. It suggests that Linear Earthworks, often thought to be boundaries or defensive structures, could actually be prehistoric canals. This reevaluation points to a far more complex and nuanced understanding of our ancestors’ engineering capabilities and societal structures. This not only challenges the archaeological community but also invites a broader discourse on the interpretation and understanding of prehistoric landscapes.

Embarking on this journey was not without its challenges, especially in an era where scepticism often overshadows scientific evidence. But, the publication of my book marks the beginning of a new chapter in archaeological research. I hope it inspires further investigation and perhaps a reevaluation of other long-standing archaeological assumptions. It’s a testament to the power of perseverance, curiosity, and the relentless pursuit of truth in the quest to understand our shared human past.

Ancient Prehistoric Canals

The response to my publication, which I had hoped would ignite a vibrant discourse within the archaeological community, instead landed with a silence that was both surprising and disheartening. Despite the rigorous research and the innovative use of 21st-century LiDAR technology to uncover previously undiscovered information about Linear Earthworks, the professional reception was lukewarm at best. It’s a curious and frustrating paradox; on one hand, my work utilises cutting-edge technology approved and disseminated by the government through the Defra website, yet on the other, it’s dismissed or labeled as conspiracy theory by a significant portion of the archaeological profession. This profession, it seems, remains tethered to older methodologies, such as satellite technology and crop mark analysis, despite the availability of more accurate and revealing techniques.

The reluctance of professionals to engage with the findings presented in my book is mirrored by the reactions on social media. Here, I encountered what can only be described as archaeological ‘Jihads’—individuals so entrenched in the teachings and texts of the past century that any new evidence or theory that challenges the established canon is met with outright denial. These reactions betray a mindset that regards peer review as a final, unassailable verdict on the accuracy of scientific and historical understanding, a viewpoint that is both myopic and detrimental to the advancement of knowledge.

This phenomenon of ‘blind obedience’ to established dogmas is not unique to archaeology; it is a pattern observable across various fields, including religious and scientific communities. It’s akin to the resistance faced by proponents of evolutionary theory against the backdrop of ‘intelligent design’ arguments. Just as some cling to religious texts as immutable truth, refusing to entertain the possibility of new interpretations or understandings, so too do certain factions within archaeology cling to outdated methodologies and conclusions, resisting new evidence that might challenge their established worldview.

The tactics employed by detractors of my work—attempting to invalidate a comprehensive theory by demanding explanations for every conceivable aspect of it—echo the strategies used by those who dispute well-established scientific theories on similarly subjective or incomplete grounds. This approach is intellectually dishonest, aiming not to further understanding but to preserve the status quo by any means available.

My experience underscores a broader issue within academia and beyond: the challenge of introducing new ideas and evidence into fields that are often resistant to change. It highlights the importance of maintaining an open, critical, but ultimately adaptable approach to new information, especially in disciplines as dynamically evolving as archaeology.

Wansdyke

In my book, I meticulously addressed every single meter of East Wansdyke, providing compelling evidence that challenges the traditional interpretation of Wansdyke as either a defensive structure or a boundary marker. My research and analysis have convincingly demonstrated that East Wansdyke was, in fact, part of a prehistoric canal system, a finding that significantly alters our understanding of the landscape and the capabilities of the people who engineered it. This conclusion was reached through a combination of detailed survey work, the application of modern technologies such as LiDAR, and a critical review of the archaeological and historical records.

However, one critic, emblematic of the resistance I’ve encountered, attempted to undermine my hypothesis by pointing to a site associated with West Wansdyke. This individual argued that because West Wansdyke was built on a ‘late Iron Age’ fortification, it must, therefore, be of Saxon origin, aiming to cast doubt on my entire thesis by focusing on this one aspect. It’s a classic example of attempting to discredit a comprehensive theory by finding fault with a single, arguably tangential, element.

In my response, I emphasised that this site, situated in West Wansdyke, falls outside the primary focus of my research on the East Wansdyke segment. More importantly, I had already anticipated such objections and addressed them directly in my book. I concluded that West Wansdyke, while geographically related, was connected to the original canal system at a later date, likely by the Romans. This connection was based on evidence suggesting that West Wansdyke is incomplete, sporadic, and differs in specification from East Wansdyke, indicating a distinct phase of construction and purpose.

The dismissal of West Wansdyke from my primary analysis was not arbitrary but a considered decision grounded in the evidence and the scope of my research. It reflects a methodological approach that prioritizes coherence, specificity, and relevance in building a historical narrative. The critique leveled against my work by focusing on West Wansdyke, therefore, misses the mark. It overlooks the rigor of my research process and the clear rationale provided for the conclusions drawn about East Wansdyke and its role within a broader prehistoric canal system.

This encounter serves as a reminder of the challenges inherent in advancing new theories in the field of archaeology, especially those that significantly depart from established interpretations. It also underscores the importance of clarity, precision, and thoroughness in both research and communication, qualities I strived to embody in my work on East Wansdyke.

West Wansdyke

We have a problem with West Wansdyke – it’s not part of East Wansdyke. This has always been a historical debate over the last 100 years. If we look at the limited archaeological evidence, we find that although it may have been a much later Canal/Dyke it is not contemporary with the East Wansdyke canal and was not built at the same time.

Excavations conclusively show that the Ditches on the East side of Wansdyke are much more profound and twice as broad. In contrast, the Banks on the East Side are much wider. We see that East Dyke was built first, as our River height model shows that most of West Wansdyke would have been flooded or marshland at the time of use.

| Location | Wansdyke | |||||||

| Bank | Ditch | Excavator notes | ||||||

| Materials | Width | Height | Berm | Width | Depth | Counterscarp | ||

| EAST | ||||||||

| Red Shore | Clay/Flints | 9.5 | 2 | N | 10 | 3.9 | Y | Green 1966 |

| Sheppard’s shore | 10 | 2.3 | N | 10 | 3.9 | Y | Pitt Rivers 1888 | |

| Brown’s Barn | 9 | 2.3 | N | 10 | 3.9 | Y | Pitt Rivers 1891 | |

| WEST | ||||||||

| Binces Lane West | Stoney | 12.5 | ?? | ?? | 3.5 | 1.7 | Y | Erskine 1990s |

| Binces Lane East | Stoney | ? | 5? | N | 6 | 2.4 | ? | Erskine 1990s |

| Compton Green | Clay marl | 13 | 0.8 | Y | 5.8 | 2.8 | Y | Erskine 1990s |

| Blackrock Lane | Silty Clay | 12.5 | 1.7 | Y | 4.8 | 2.7 | ? | Erskine 1990s |

| Park farm | Stones | 10 | 0.4 | Y | 5.5 | 2.4 | Y | Erskine 1990s |

| Fairy Hill | 13 | ? | Y | 6.5 | ? | Erskine 1990s |

When the waters receded (possibly Early Iron Age period), it is possible that the Dyke was extended, or the more probable event of East Wansdyke after it dried up was turned into a roadway and what we see in West Wansdyke is the extension of the road, and hence it is wider than in the East.

We also see more shallow ditches as they were not used for water but to obtain soil for the walkway and become drainage ditches.

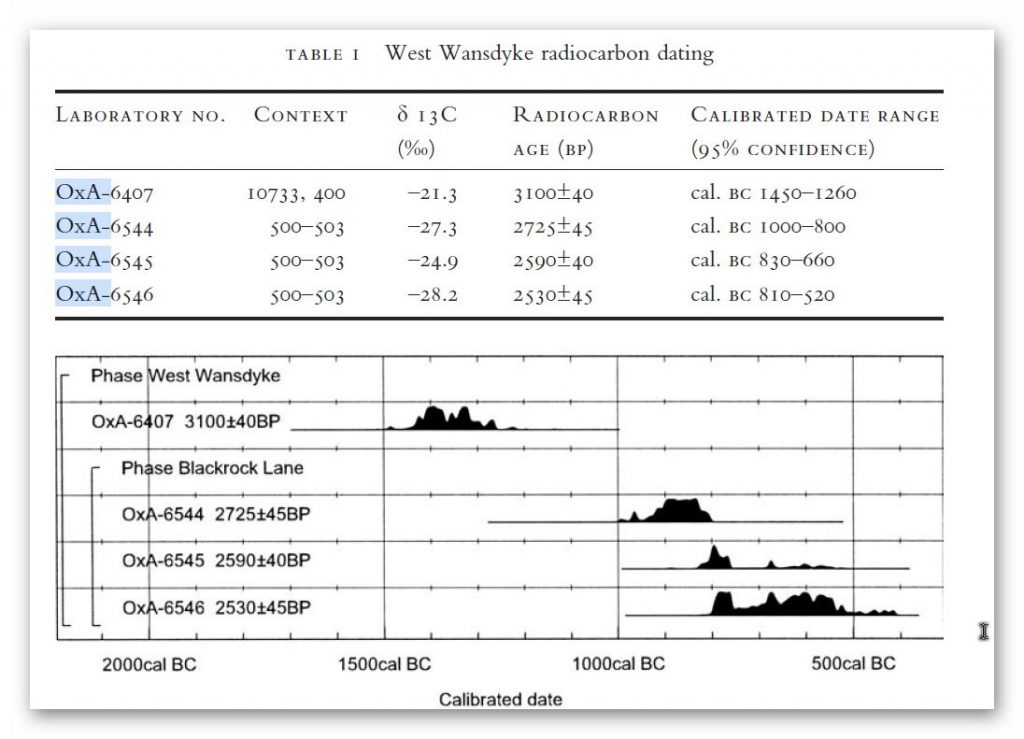

Indeed, we know the Romans used this as a road and always had drainage ditches, usually on both sides. This is supported by carbon dating at Erskine’s excavation at Blackrock Lane, where the section appeared to have been sealed by the primary bank material. One of these layers contained significant concentrations of woody oak charcoal.

Samples of this material were submitted to the Ancient Monuments Laboratory for radiocarbon dating to provide a possible construction of the bank. Unfortunately, as shown in the table below – sadly, as standard when scientific evidence disproves the current archaeological narrative – it is ignored and classified as an error.

Table 1. Erskine, Jonathan. (2007). The West Wansdyke: an appraisal of the dating, dimensions and construction techniques in the light of excavated evidence. Archaeological Journal. 164. 80-108.

The other missing aspect shown in East Wansdyke and not West Wansdyke was the massive connection to Barrows and Flint Pits. Again, this connection is not seen on West Wansdyke, which may help date this monument as the barrows were of the Bronze Age or earlier and as we have seen from the carbon dating evidence at Blackrock Lane much earlier than its 1500 BCE date.

Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

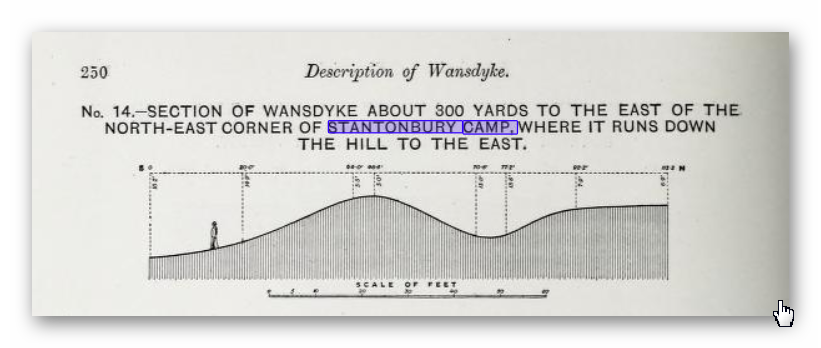

If we look at the Scheduled parts of the Wansdyke – we see that the East is very much intact, but the West is sporadic at best, and it’s hard to find a logical link to all the Dykes that seem to only appear over hills and not in the valley’s – which in my view would have been flooded in the Mesolithic and hence the west sections addition after East Wansdyke’s construction – probably by the roman’s who may have utilised the Dyke system for their own transportation reasons. But for the sake of scientific curiosity, let’s take a detailed look at Stantonbury Hill site, which is classified as an Iron Age Camp, with Wansdyke making up one of the defensive banks – but before we delve deeper into the field archaeology of the site – I feel I must clarify the use of the classification of ‘Iron Age Fort’ by archaeologists.

All sites that sit on top of hills and have ditches are called Iron Age Forts – sadly I have yet to find a single location that is either ‘Iron Age’ or a ‘Fortification’ as not a single dead body from slaying has ever been found and all the so called defensive ditches EVER!! Yet the archaeology world continues to use this misleading classification that confuses the public as if it has been qualified and proven. So, back to Statonbury camp. The only investigation of this site was made by Fox and Fox in 1956 as part of their survey of Wansdyke in the publication ‘Wansdyke reconsidered.’ It should be noted that Historic England does not have an account with their scheduling as no excavation work has ever been undertaken, and so only field walking has been undertaken, and so the results are subjective to the field walker.

In Fox’s publication they also question this linkage of East and West Wansdyke through other even older publications and field surveys that resulted in questioning the logic of dating this linear earthwork. That great antiquary, Sir Richard Colt Hoare, had his doubts about the identification, which he endeavoured to suppress in his account of the earthwork in Ancient Wiltshire,

‘ Hitherto we have been enabled to trace the course of Wansdyke with certainty and success through Somersetshire, but on approaching the neighbouring county of Wiltshire we enter upon a new and doubtful field of inquiry respecting the direction as well as the formation of this celebrated rampart.’

His own observations in the field had shown him that in this central sector ‘ it bears the decided appearance of a Roman causeway, not of a Belgic or Saxon boundary and yet he felt obliged to support the current view that road and dyke were identical because he was convinced that the Wansdyke was continuous and he could find no alternative course for it in the area. Sir R. C. Hoare also observes, the camps appear to have been added to the Dyke, not the Dyke formed to connect the camps ; which may be noticed especially at Stantonbury Camp, the second on the line of the course of Wansdyke through Somersetshire.

They continue……

General Pitt-Rivers, also had misgivings, ‘ the Dyke he comments, in the Heddington region,’ is of very low relief everywhere on this line and it has often been questioned whether it is a dyke or a road’, and his suspicions were again aroused at a point west of Morgan’s Hill and on Bowden Hill near Lacock’.

On Statonbury Camp there are not very helpful and report that:

Stantonbury is a univallate Iron Age hill-fort enclosing some 30 acres on the crest of the hill : until very recently it was waste ground going back to thorn scrub and islanded in dense woodland, as can be seen on the air-photo (Pl. VIIIB). The hill top (580 ft.) commands a wide view : from here the whole of the countryside traversed by West Wansdyke can be seen, Maes Knoll to the west. Odd Down to the east, as well as an uninterrupted stretch northwards to the Avon valley and the Cotswolds beyond. From here, the major alignment was probably planned (fig. 19 and p. 37).

In 1956-7 the hill top has been ploughed again, and the much reduced Iron Age defences are visible on the edge of the cultivation. It appears to us that Wansdyke was not constructed along the north-facing hill slope, and that as at Old Oswestry hill-fort, on Wat’s Dyke in Montgomery, the Iron Age defences were deemed sufficient. There is, however, as General Pitt-River’s level section shows, a steep scarp below the traces of the ploughed-in Iron Age ditch, which may be artificial and post-date the hill-fort, but this is uncertain. East of the fort, in field 20, which is now occupied by a plantation and a pheasantry, the Dyke continues as a scarp for as far as we were able to trace it through the nettles and undergrowth. Below the 500 ft. contour, the large bank and ditch reappear in the dense woodland, and emerge beside the lane leading to the road to Stanton Prior, where the earthwork measures 75 ft. overall.

So according to Fox and Fox Wansdyke stops short and accepts the North Face is the Iron Age Site – therefore if the Wansdyke had been cut to the north of the site – the Iron Age fort replaced it – which is not as the Jihad had claimed?

So where did he get this ‘ground-breaking’ revelation? For this we must go not a peer reviewed book but a web site ‘wansdyke21.org.uk’ by Robert Vermaat

He suggests that: It has been suggested by Fox & Fox that Wansdyke did not actually use Stantonbury Camp, the ditch stopping short of the Iron Age defences by several metres. However, Burrow showed in 1982 that this was incorrect. Although the western slope is much disturbed by quarrying and the lower slopes by cultivation, Wansdyke can still be traced quite well at several points on the hill. As with Maes Knoll, the northern defences are more prominent than those on the south side. As Wansdyke joins the defences here, it can be argued that, as was the case at Maes Knoll, the northern defences were refurbished when Wansdyke was constructed, neglecting the south side which was without use for the builders of Wansdyke.

If only we had £64 to see this so called evidence from Field walking by burrows (as we know it was not excavated and LiDAR was not in use)!!

Fortunately, we have now obtained high resolution LiDAR images of Statonbury Camp and we can see that Wansdyke goes over the hill in a strange ‘wibbly wobbly’ way rather than a straight line – which we see either side of the hill from much shallower ditches. This suggests that this area was not built completely at the same time and the Hill Dyke is older than the flat ground levels that surround the hill.

My estimation from the evidence found in the smaller ditches is that they are Roman (and hence straight) in origin that connected to the earlier prehistoric Dyke over Statonbury Hill the archaeologists call West Wansdyke (part of). The path over the hill indicates that the builders were attempting to locate natural springs as they built the Dyke to supply it with water and hence the strange pathway.

Closer inspection of the Dyke as it approaches the ‘Iron Age Site’ suggest that it splits and moves the bank from north facing to south facing which Fox had seen as a terminus of the Dyke for it reached the Fort. LiDAR clearly shows that the ditch moves to the south side of the bank and continues to create the East side of the fort finally terminating in the South.

Also the shape of the fort is not consistent as it has rounded edges in the SE and SW regions but flat T-Junctions in the NE and NW where it meets Wansdyke – indicating it was added to the existing Wansdyke canal either at the time of construction or a later date.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Prehistoric Britain Blog Review - Prehistoric Britain