The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

Contents

Introduction

Over the recent span of years, there has been a marked tendency to present images of climatic upheaval—storms that rend the fabric of local communities and touch the lives of individuals with their tempestuous hands. In the discourse on flooding, an almost theatrical emphasis is placed upon the metrics of catastrophe: the voluminous descent of rain and the gales’ ferocious velocity. Amidst these narratives, a phrase of gravitas, ‘since records began,’ is often delicately woven, lending weight to the tales of unprecedented climatic fury that segment our years into records of seasonal extremities. (The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain)

Yet, one must pause to reflect upon the foundations of these records, for they rest upon the daily observations that commence from the year 1914. To herald any year as a harbinger of climatic extremes, such as the year 2023, without a deeper contemplation, may inadvertently serve the narratives of climate change and political agendas that have woven through our collective discourse for two decades. However, it behooves us to remember that the annals of our climate, such as the England and Wales Precipitation series tracing back to 1766 and the venerable Central England Temperature series originating in 1659, bear witness to a longer, richer dialogue between humanity and nature. These records, born from the dedication of amateur meteorologists, offer a broader canvas against which to measure our current experiences. Yet, paradoxically, they are oft relegated to the shadows, dismissed in favor of more recent measurements.

In this light, one might contemplate the wisdom of recognizing the depth and breadth of our climatic history, as it offers a more textured understanding of our present and a more informed foundation for our discussions on climate and its impacts on human society. Bronowski, with his eloquent reverence for the intricate tapestry of human knowledge, might have urged us to look beyond the immediate spectacle, to value the contributions of those who have watched the skies long before the modern era, and to consider the long conversation between humanity and the weather in our quest to comprehend the forces that shape our world.

Sky News Online:

“England and Wales have seen the wettest summer for 100 years, according to MeteoGroup. Rainfall for June, July and August was 362mm (14.25in), making it the wettest summer since 1912. The average summer rainfall across the UK is 226.9mm (8.9in). MeteoGroup forecaster Nick Prebble said this summer is set to be the fourth wettest since records began in 1727. The record for the UK’s wettest summer is 1912 when 384.4mm (15.1in) of rain fell.” (The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain)

Let us delve into the fabric of the British summer, as narrated by the Met Office, revealing a tapestry less illuminated by the sun’s grace than in years past. A summer, they tell us, that may be recorded in the annals as one of the dullest, with a mere 399 hours of sunshine until the twilight of August, shadowed only by the year 1980’s modest 396 hours. This narrative unfolds in the aftermath of a Bank Holiday painted in the hues of unsettled weather, where rain and flood alerts draped many a UK landscape.

Joanna Robinson, a sage of weather from Sky News, recounts a tale of a season that began with the wettest June recorded, followed by a July that, too, was cradled in wetness. Yet, as the days of summer waned, the weather found a semblance of calm, only to be disturbed once again as August drew to a close. She speaks of the jet stream, that ethereal conveyor of weather, which, in its wanderings, steered storms across the British isles that might have otherwise passed us by.

The summer of 2007 looms in recent memory, its rainfall second only to records beginning in 1912, yet August of this current summer hints at being the driest and sunniest. Such observations provoke exclamations of dismay and declarations of climate change’s grip upon our world. Yet, a closer scrutiny, a peering into the depths of our climatic past, reveals a narrative less singular in its direction. The year 2007, while remarkable for its summer deluge, does not rank among the highest in annual rainfall, settling instead into the seventeenth position over the last century.

Our engagement with the elements, marked by the ebb and flow of rainfall, stretches back over centuries, with periods of intense precipitation, such as the decade spanning 1870 to 1880, punctuating our history. And between the notable years of 2007 and 2012, the year 2010 emerged as the eleventh driest, a reminder of the natural oscillations that characterize our climate.

Grote Mandrenke

Turning our gaze to the winds and gales that sculpt our coastlines, history offers us a lens through which to view these forces in a broader context. The ‘Grote Mandrenke’, a tempest from the annals of the fourteenth century, wrought devastation unparalleled, claiming thousands of lives and altering landscapes and architectures. This event, among others, serves as a testament to the dynamic and often turbulent relationship between humanity and the environment.

In this reflection, inspired by the thoughtful considerations, we are invited to contemplate the narratives of weather and climate not as isolated phenomena but as part of a complex interplay of natural forces, historical events, and human experiences. Through this lens, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricacies of our world and the myriad ways in which the past informs our understanding of the present and the future.

In the reflective prose, let us explore the further reaches of our historical and environmental saga, where the dance between humanity and nature continues its timeless rhythm. As the great storm of 1362 stretched its wrath into the North Sea, it conspired with the tides to birth a tempestuous offspring—the storm surge. This phenomenon, a marauder of the coasts, reshaped the contours of the European shore, leaving ports from England to Denmark in ruins, and forever altering the dialogue between land and sea.

Yet, this cataclysm, while monumental, is not an isolated whisper in the annals of our planet’s climatic history. It echoes a more ancient, more profound narrative that commenced with the first settlers in the Mesolithic period. These early denizens of the land faced the capricious moods of a world freshly emerged from the clutches of the last Ice Age—a time when the land itself was a protagonist in a story of transformation and survival.

The landscape, a silent historian, bears the scars and tales of these epochal changes. The retreat of the ice sheets some ten thousand years ago unleashed waters that dwarf our contemporary measures of rainfall, inundating the land with a deluge that would reshape its very skeleton. The annual rainfall pales in comparison to the volumes discharged in this great thaw, where millions of millimeters of water sculpted the British Isles into a new form, carving out riverbeds and creating the flood plains we know today.

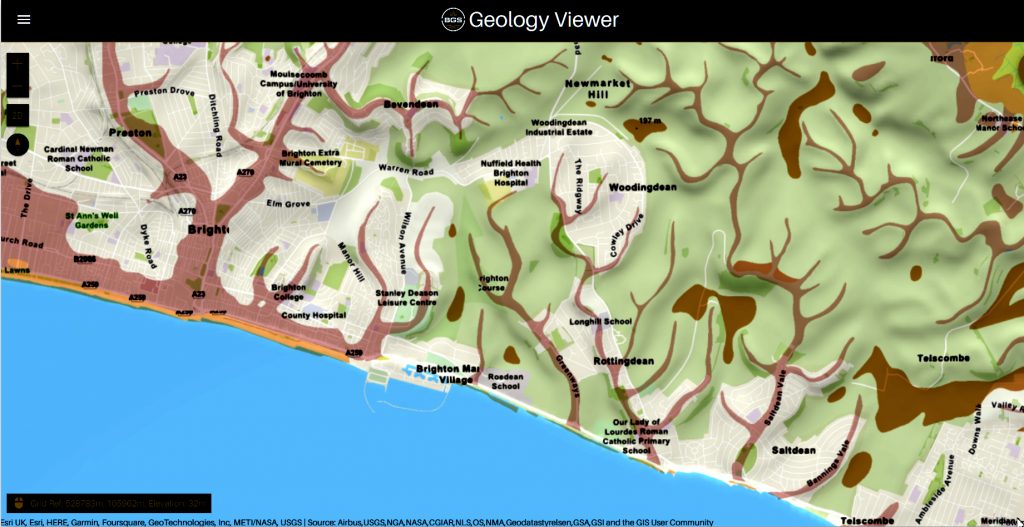

British Geological Society

These ancient watercourses, now hidden beneath layers of sediment and time, are revealed to us through the meticulous cartography of the British Geological Society (BGS). Their maps unfurl a tapestry of geological memory, showing us the remnants of vast paleo-river systems that cradled the waters of the past. The flood plains, marked by their unique sedimentary compositions, are not merely areas prone to contemporary flooding but are the fingerprints of ancient rivers that once dominated the landscape.

Our Mesolithic ancestors, attuned to the rhythm of this waterlogged world, chose the margins of these flood plains for their sacred sites and communal gatherings. Stonehenge, that enigmatic structure, stands as a testament to their profound connection with the land and its waterways. They navigated the flooded realms, moving from isle to isle, their lives intertwined with the ebb and flow of the waters.

The evidence of these ancient flood plains and their impact on human settlement and activity is etched into the very bedrock of our island. A study of the BGS maps reveals a subterranean network of what once were mighty rivers and channels, especially around areas of chalk bedrock like Stonehenge. These geological whispers invite us to consider how our landscape has been shaped by water’s forceful hand, guiding our ancestors and shaping the course of our collective history.

In this contemplation, inspired by Bronowski’s reverence for the intertwining of science, history, and human endeavor, we are reminded of the enduring legacy of our planet’s natural forces. They beckon us to view our present and future through the lens of the deep past, understanding that the stories of storm surges, flooding, and climate are chapters in a much longer narrative of earth and humanity.

Embarking on a journey of inquiry and reflection, we delve into the enigma of Britain’s dry river valleys. These landscapes, now silent and devoid of flowing waters, serve as a testament to the dynamic and ever-changing canvas of our planet’s geological and climatic history. Known to archaeologists, geologists, and the curious layperson alike as ‘Dry River Valleys,’ these formations beckon us to ponder the forces that sculpted them and the epochs they have witnessed.

The conventional wisdom posited that the distinctive contours of these valleys, nestled within the chalk hills, were the handiwork of the Periglacial Phase of the Quaternary Period—a vast expanse of time that commenced around 2.6 million years ago. Yet, the precise moment of their birth remains shrouded in the mists of prehistory, without concrete evidence to mark their genesis.

Geology, a discipline ever ripe with evolving theories and reinterpretations, suggests these dry valleys were carved by the relentless flow of water, eroding topsoils and smoothing the underlying chalk during the thaw that followed an ice age. Yet, the Quaternary Period is marked by a succession of ice ages, each leaving its indelible mark upon the land. This presents a quandary for those who seek to understand not just the creation of these valleys, but the epochs in which they thrummed with the lifeblood of flowing rivers.

Post-Glacial Flooding

For archaeologists and geologists, the puzzle lies in discerning which ice age’s thaw sculpted these valleys into the landscape. The challenge is not merely academic; it bears significant implications for understanding the human story intertwined with these natural features. The timing of water coursing through these valleys could illuminate periods of human activity, migration, and settlement, shedding light on the ancient peoples who once lived alongside these now-vanished rivers.

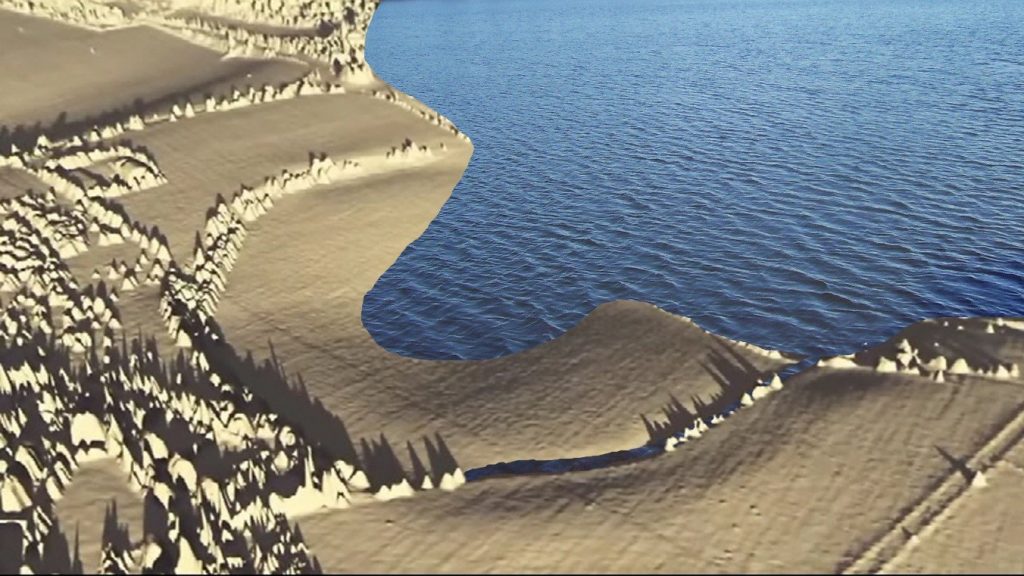

Geological maps and studies hint at the existence of great rivers that once traversed the British Isles, sculpted by the monumental release of water at the conclusion of ice ages. The last great thaw, occurring some 17,000 years ago as the ice sheets, towering over two miles high in places, receded, would have unleashed floods of epic proportions. This deluge, the most significant in recent geological history, would have transformed the landscape, including the Valleys of the South Downs, far from the ice sheet’s edge.

The intrigue of these dry river valleys lies not solely in their geological formation but in the stories they hold of a world dramatically different from our own. To understand when these valleys last echoed with the sound of flowing water is to peel back layers of time, revealing insights into the climatic shifts that have shaped the earth and influenced the course of human civilization.

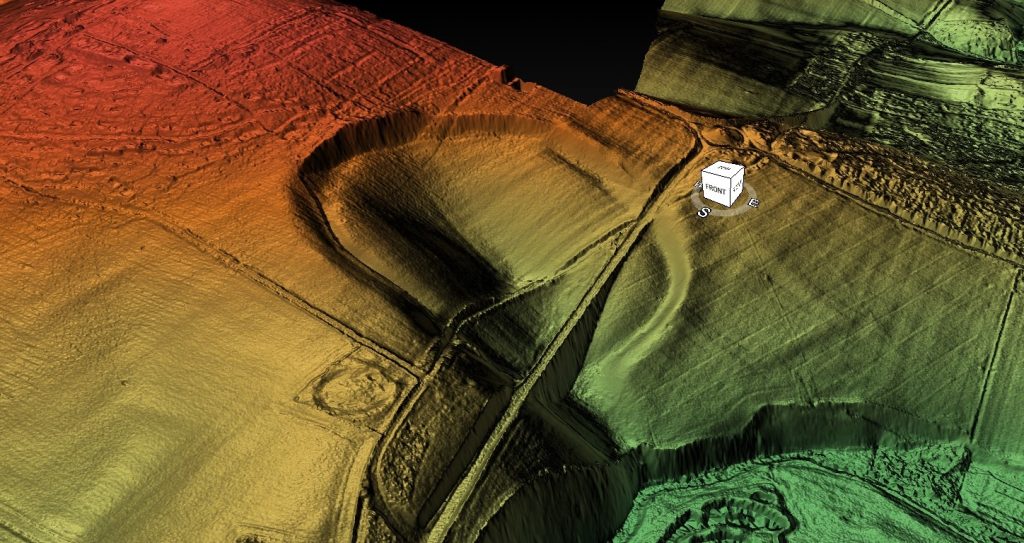

We encounter a paradigm shift in the understanding of Britain’s dry river valleys. Modern geological consensus now acknowledges that these features were carved not by the slow, grinding advance of ice, but by the dynamic and erosive power of water. This revelation comes from observing the profound examples of soil erosion and the creation of valleys, where millions of gallons of water, moving with relentless force, stripped away layers of earth down to the bedrock.

This narrative finds vivid illustration in the South Downs, where the cliffs and valleys bear silent testimony to ancient, post-glacial rivers. The region, much like the area surrounding Stonehenge, rests upon chalk sedimentary bedrock, shaped by the flows of yesteryear. The presence of these ancient watercourses is betrayed by the layers of sand, silt, and clay that comprise the subsoil, visible in the deans (valleys) of the South Downs and most strikingly on the faces of the chalky white cliffs. These cliffs, sculpted by the sea, offer a cross-section view into the past, revealing the sedimentary layers left by prehistoric rivers.

Contrary to earlier interpretations that attributed the formation of these geological features to windblown loess or wash from valley walls, the evidence suggests a different story. The discovery of sandy sediments, embedded within the chalk and lying in close proximity to the current topsoil, points to a more dramatic origin. These remnants of ancient rivers, dating back approximately 15,000 years to the aftermath of the last great melt, challenge the prevailing theories.

The puzzle for geologists and archaeologists alike lies in the thin veil of topsoil that covers these ancient sediments. If these valleys were as ancient as previously believed, the question arises: where has the expected accumulation of topsoil gone? Furthermore, if topsoil erosion occurs at the rate some experts claim, how do we account for the presence of 18 inches of topsoil atop the chalk in the present day?

These questions invite a reevaluation of our understanding of the landscape’s history, suggesting that the processes of erosion and sedimentation may not conform to the simplistic models previously proposed. The narrative of the South Downs and similar landscapes across Britain is not merely a tale of geological change but a reflection of the complex interplay between the earth’s natural forces and the passage of time.

We find ourselves at a crossroads of questions concerning the sedimentary timelines and the environmental narratives of our ancient landscapes. The enigma of the seemingly scant topsoil overlaying the remnants of prehistoric river beds in places like the South Downs raises profound questions about our understanding of climatic events and geological processes. Are we on the brink of uncovering evidence of a massive climatic upheaval yet to come, one that could dramatically alter the topsoil? Or, perhaps more intriguingly, have we misdated the dry river valleys and the prehistoric river beds that cradle the foundations of our ancient history?

The puzzle deepens as we consider the architectural legacies of our ancestors, such as Woodhenge and the enigmatic site known as Durrington Walls. These ancient monuments, constructed with a profound understanding of their environmental context, may hold clues to the climatic and geological conditions of their time. The location and design of these structures, aligned with natural features and possibly with an awareness of flood plains and waterways, suggest a sophisticated interaction with the landscape that transcends mere habitation and ventures into the realm of reverence and ritual.

The construction of Woodhenge, positioned near the curious formation of Durrington Walls, invites speculation about the relationship between human society and the natural world in prehistoric times. Were these monuments erected in response to the environmental challenges faced by their builders, such as flooding or the need to navigate and control water resources? Or did they serve as markers of significant geological features, such as the dry river valleys, embedding within their construction a coded knowledge of the landscape’s history and its cyclical transformations?

These questions compel us to reexamine our interpretations of the archaeological record, challenging us to integrate geological evidence with the cultural and spiritual dimensions of ancient constructions. The apparent discrepancy in the sedimentary record, marked by the proximity of ancient river sediments to the present-day topsoil, may not only point to gaps in our geological dating but also to a more complex understanding of how our ancestors interacted with and adapted to their environment.

Durrington Walls

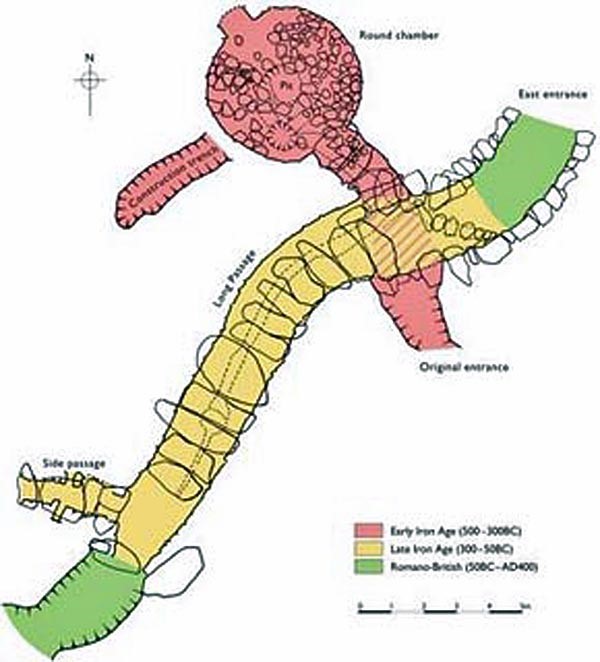

When you look at Durrington Walls, the first thing that strikes you is that it seems incomplete; it looks like a half-circle from aerial photographs, and from the ground you get, a sense of it only being half-finished. However, most illustrations include the easterly section because magnetometer surveys show that there are more ditches under the surface, although you might question their purpose, as it is not apparent. The easterly side of the site was clearly built much later than the original Westside. The East bank is smaller and does not match the initial ditch and moat specifications, which was roughly 5.5 m deep, 7 m wide at its bottom, and 18 m wide at the top. (The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain)

The bank was 30 m wide in some areas. The bank and ditch indicated by the magnetometer surveys are less than half that depth; the bank is only about a third of the size of that on the Northern side. The current theory and plan of Durrington Walls do not stand up to investigation, for clearly, the Eastern side of the camp was added later when the prehistoric groundwater had started to recede.

So what was its original use?

To answer that question, you must look at the site’s terrain, position and layout. The first thing that hits you is that the site is not flat! In fact, it’s a huge bowl.

The suggestion that our forebears might have chosen to establish settlements in locations that, to the modern eye, appear prone to flooding, invites a deeper investigation into the logic and environmental understanding of these ancient communities.

The case of Durrington Walls, traditionally interpreted as a settlement due to the discovery of roundhouse foundations, challenges contemporary notions of ideal habitation sites. The prevailing wisdom that discourages camping on a slope due to the risk of water runoff highlights a modern bias towards flat, stable ground. Yet, the archaeological insistence on Durrington Walls as a settlement, despite its topographical peculiarities, might be overlooking the site’s strategic significance in relation to the environmental conditions of the time.

Harbour

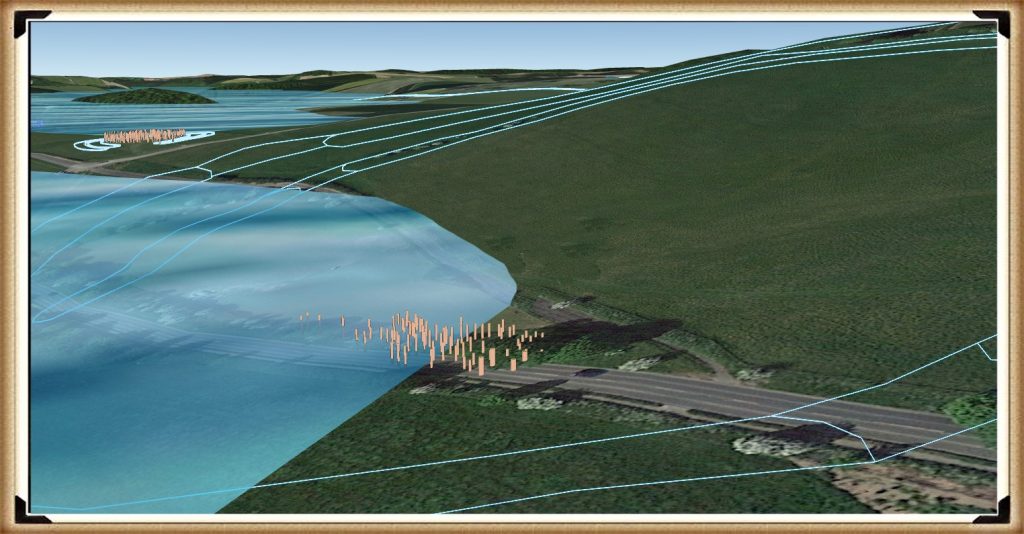

If we entertain the notion of significantly higher prehistoric groundwater levels, Durrington Walls transforms from a seemingly ill-chosen settlement into a potential natural harbour. The site’s configuration, with shallow sides ideal for mooring boats and a central ravine providing depth for watercraft, coupled with the remains of substantial external walls, suggests a sophisticated understanding of landscape and water management by its builders. Such a harbor, protected by formidable chalk walls, would have been a marvel of prehistoric engineering, offering shelter from the elements and facilitating trade or travel.

Woodhenge’s dual entrances further support the hypothesis of a water-centric landscape. One entrance aligns with Durrington Walls, suggesting a terrestrial connection, while the other, leading towards what would have been the ancient shoreline, implies a relationship with waterways. The presence of groundwater at Woodhenge, inferred from magnetometer surveys and the peculiarities of the site’s layout, underscores the adaptability and ingenuity of prehistoric peoples in harnessing their environment.

The evolution of the landscape, mirrored in the receding shoreline over millennia and the adaptation of human structures to these changes, reveals a dynamic interaction between our ancestors and their surroundings. The modern road, tracing the ancient shoreline’s path, serves as a tangible reminder of the deep history embedded in the land.

This reconsideration of Durrington Walls and Woodhenge as components of a prehistoric landscape intimately connected with water challenges us to think beyond conventional archaeological interpretations. It suggests that our ancestors were far from foolish in their choice of settlement locations. Instead, they possessed a profound understanding of their environment, selecting sites based on a complex array of factors that included access to water, natural protection, and the strategic advantages these locations offered.

We should not be too surprised by this, as lakeshores and coastlines still have paths along with them today so that we can fully enjoy them. There is no reason to believe that prehistoric people did any different 8,000 years ago, and such a path would also have a practical purpose as the shorelines were used as a mooring site. If we are correct about the road and the mooring points, is it possible to find post holes here under the ground?

Unbelievably, the answer is yes!

Wainwright, in his excavations of Durrington Walls, discovered lots of them. Without a shoreline, the post holes would look random and not make much sense. However, as soon as the groundwater flooding is added, their function becomes apparent: they held mooring posts, as that is the natural landing area for boats coming to and from Stonehenge, Avebury or Old Sarum. But are there other sites that have walls to protect them from the weather?

Avebury

Navigating through the mysteries of Avebury and its ancient landscapes, we find ourselves in the midst of a dialogue that blends the profound insights of archaeology with the nuanced understanding of geology, much in the spirit of Jacob Bronowski’s interdisciplinary exploration. Avebury, nestled within the chalkland of the Upper Kennet Valley, presents a fascinating case study of human interaction with a dynamically changing environment.

The positioning of Avebury on a low chalk ridge, elevated above the surrounding landscape, and its proximity to the Marlborough Downs, speaks to the strategic selection of this site by our ancestors. The discovery of flint artifacts dating back to the late Mesolithic period suggests a long history of human presence, drawn perhaps by the natural resources and the strategic vantage point offered by this location.

The post-glacial flooding that reshaped the landscape around Avebury, transforming it into an almost island-like monument surrounded by waterways, highlights the profound impact of natural forces on human settlements. The effort to maintain Avebury’s island status through the construction of ditches and large banks reflects a determined human response to the changing environment, aiming to preserve the symbolic or functional significance of the site.

The estimated 1.5 million working hours required to construct the Avebury monument, involving 200 people working full-time for three to four years, underscores the monumental effort invested in this endeavor. This contrasts sharply with the even more staggering effort estimated for the construction of Silbury Hill, suggesting a remarkable dedication of resources and labor to these ancient projects. The discrepancy in the estimated working hours needed to move the respective volumes of chalk at Avebury and Silbury Hill raises intriguing questions about the methods, technologies, and organizational structures of prehistoric societies.

These ancient monuments, Avebury and Silbury Hill, stand as testaments to the ingenuity and resilience of our ancestors, who, faced with a world marked by extreme weather events and changing landscapes, sought to leave their mark through these colossal earthworks. The monumental scale of these projects, achieved without the modern machinery or technological aids available today, invites us to reconsider the capabilities of ancient societies and their profound connection to the landscapes they inhabited.

This is just another fact that does not make sense! –

There is just no consistency in archaeological findings; it’s all subjective, and quite frankly, wrong!

The suggestion that monuments like Avebury evolved gradually over centuries, with their ditches deepening from a modest one meter to the monumental eleven meters over 5,000 years, presents a compelling narrative of continuous human engagement with these sites. This slow but persistent expansion and deepening of the ditches could indeed offer a plausible explanation for the archaeological conundrum of the tools used in their construction.

The incremental growth of these monuments suggests a process deeply intertwined with the rhythms of prehistoric life, where the maintenance and expansion of the ditches became part of the community’s ongoing relationship with their environment and their heritage. The gradual excavation of the ditches, possibly for purposes of ritual cleansing, defense, or as part of expanding the monument’s scope, would have allowed for the use of the simple tools available at the time. This contrasts with the daunting task of constructing such massive earthworks within a single generation, which would have required a level of resources and coordination that seems less plausible in the absence of sophisticated tools and technologies.

Giant Ditches

The analysis of the ‘chalk mountain’ created from the excavated material offers fascinating insights into the purpose and symbolism of the monument. The calculation that the bank could have originally stood at least 15 meters high, with a potential for reaching 20 meters when accounting for the compression of chalk and the inclusion of air gaps, underscores the monumental effort invested in these structures. This towering presence would have dominated the landscape, serving as a potent symbol of the community’s identity, beliefs, and capabilities.

The bank’s considerable height, derived from the volume of chalk moved from the ditches, also speaks to the technical understanding and engineering skills of the people who built these monuments. The manipulation of the landscape on such a scale, with the tools and knowledge available at the time, demonstrates a sophisticated grasp of materials and a deep connection to the land itself.

This perspective, which sees the monuments growing organically over time, enriches our understanding of the relationship between prehistoric societies and their monumental creations. It suggests that these structures were not static symbols imposed upon the landscape but were dynamic and evolving entities that reflected the changing needs, beliefs, and aspirations of their builders.

The endeavor to construct a 15-meter-high wall, especially within the context of ancient monumental architecture, invites a nuanced exploration that bridges the gap between archaeological theory and the lived realities of prehistoric communities. The suggestion that such walls were defensive structures, yet paradoxically positioned in a manner that would ostensibly favor attackers, propels us into a deeper inquiry into the motivations and environmental challenges faced by these ancient builders.

The comparison with Durrington, where a high wall ostensibly serves a protective function against wind and storms for boats, suggests a pragmatic approach to construction that transcends mere defensive purposes. This insight challenges the notion of monumental walls as solely ceremonial or defensive and invites consideration of their role in mitigating the environmental conditions of the time.

The archaeological pivot to ‘ceremonial’ explanations in the face of such paradoxes, while often serving as a placeholder for the unknown, may indeed overlook the practical interactions between these ancient communities and their volatile climates. The humorously termed “God of pointless constructions and practices” belies a critical gap in our understanding of the symbiotic relationship between human societies and their environments.

Undergound Bunkers

The suggestion that the weather in the past was more severe, and the construction of shelters and walls was a response to these conditions, is compelling. This perspective is supported by the existence of souterrains or underground structures, which served as refuges from the harsh weather. These structures, varying in design and function across regions, exemplify the adaptability and ingenuity of ancient communities in the face of climatic adversity.

The regional variation in the design of souterrains, from fogous in Cornwall serving as larders to other forms of underground shelters, underscores the diversity of responses to environmental challenges. This diversity not only highlights the practical considerations driving the construction of monumental and subterranean structures but also reflects the rich tapestry of cultural practices that evolved in tandem with the changing landscapes and climates.

The souterrains of Ireland, often colloquially termed ‘caves’, embody a fascinating segment of the archaeological and cultural landscape, rich with historical significance and imbued with the mysteries of the past. The scholarly works of individuals like A.T. Lucas and the comprehensive study by Clinton in 2001 have provided invaluable insights into these subterranean structures, offering a window into their distribution, associated settlements, functions, and the chronology of their usage.

Originating from the French term for “underground passageway,” souterrains were integral to the communities that constructed them, serving purposes that extended beyond the mere architectural or ceremonial. These underground galleries, often associated with settlements and ringforts, reflect a blend of ingenuity and necessity, designed to withstand the trials of their times.

Constructed by digging out earth and lining the created spaces with stone slabs or wood, souterrains were reburied to integrate seamlessly with the landscape. In instances where they were carved directly into rock, such elaborate preparations were unnecessary. Their functions, far removed from burial or ritualistic uses, leaned towards the practical, serving primarily as food stores or refuges during periods of conflict. The presence of souterrains within or adjacent to ringforts, and their dating to periods contemporary with these structures, suggests a synchronization of defensive strategies and domestic planning.

The utilization of ogham stones as structural elements within souterrains, repurposing ancient script-bearing stones as roofing lintels or doorposts, underscores a fascinating intersection of cultural heritage and architectural necessity. Such practices highlight the adaptive reuse of materials and the deep-rooted connection between the physical and the symbolic in Irish heritage. The ‘cave of the cats’ at Rathcrogan stands as a prominent example, where the widened natural limestone fissure incorporates ogham stones, weaving together the threads of history, architecture, and mythology.

The distribution of souterrains in Ireland, particularly concentrated in certain counties, speaks to the geographical and environmental factors that influenced their construction. These underground structures, with their often obvious entrances, challenge our modern perceptions of secrecy and security, suggesting that their protective function was balanced with the practical needs of accessibility and use.

The first thing that strikes you as strange is the fact that these landscape features are categorised with different names in different locations:

Earth Houses – Modern use

Fogous – Cornwall

Pictish Houses – Found in Scotland (confusion arises here as some are only partially subterranean) unlike the Earth Houses in the same region.

Caves – Ireland

It’s quite literally an archaeological mess. And the reason for this mess is those archaeologists don’t understand why they were built, so they gave them local names, unlike barrows and Stone circles and henges, which appear in the same areas but with a unified name to save confusion. So how what can we find out about these structures that will help us understand why they were built?

Location, Location, Location

If we look at the minimal archaeological evidence, we do see a defined pattern of construction. For example, in Cornwall, we have found to date a collection of fifteen ‘fogous’. According to archaeologists, this is a proposed use for fogous, a refuge during raiding trips as they are close to the sea. Sadly, if you search deeper, you see them in non-coastal areas and even in the middle of Dartmoor (Lade Hill Brook), where it’s called a Beehive Hut?

The problem with looking for such objects in Devon is that hundreds of ‘caves’ dotted around from the days of tin mining, and therefore an almost impossible to distinguish a prehistoric mine opening from a fogou.

The exploration of subterranean structures across the British Isles and their potential functions opens a fascinating chapter in the study of prehistoric human adaptation to environmental challenges. The presence of fogous in Cornwall, notably the example at Carn Gwavel Farm on the Isle of Scilly, exemplifies the ingenuity of ancient communities in creating shelters that blend seamlessly with the landscape. These underground chambers, with their distinctive S-shaped curves and corbelled construction, suggest a level of architectural sophistication aimed at addressing specific needs, whether for storage, habitation, or protection.

The orientation of fogous towards the SW-NE axis raises intriguing questions about their purpose. While some might speculate a religious or ceremonial significance, the practical considerations of climate and environmental exposure cannot be overlooked. The architectural similarities between fogous, chamber cairns, and passage chambers across different regions—each adapted to local conditions and available materials—underscore a widespread practice of constructing subterranean spaces for varied uses.

In regions like Ireland and Scotland, where these structures are more commonly found and referred to as ‘caves’ or ‘earth houses,’ their abundance points to a shared cultural practice of utilizing underground spaces. The absence of similar structures in areas like Devon, Dorset, Somerset, and Wiltshire, juxtaposed with the concentration of other prehistoric monuments, suggests regional variations in responses to environmental and social pressures.

The situation in Wales, with its chambered cairns and passage chambers, adds another layer to this complex tapestry. The discovery of bodies within these structures has led to their classification as burial sites, yet the possibility that their original purpose evolved over time warrants consideration. The comparison to modern bunkers, which have found new uses beyond their original intent, illustrates the fluidity of human interactions with built environments.

Tornadoes

The hypothesis that these subterranean shelters were constructed in response to severe storm conditions, akin to practices in contemporary hurricane-prone areas of the USA, highlights a timeless human priority: the need for protection against the elements. This perspective offers a compelling narrative of prehistoric resilience and adaptability, suggesting that the construction of such shelters was a rational response to the challenges posed by a dynamic and sometimes hostile environment.

Understanding the motivations behind the construction of fogous and similar structures requires an interdisciplinary approach that considers archaeological evidence, environmental science, and historical climatology. The severity of prehistoric storms, informed by geological indicators of post-glacial flooding and climate change, provides a backdrop against which the necessity and ingenuity of these ancient shelters can be fully appreciated.

In contemplating these ancient structures, we are reminded of the enduring human capacity to innovate and adapt to the world’s ever-changing face. The legacy of fogous and their counterparts across the British Isles and beyond speaks to a deep-seated human instinct to seek shelter and safety in the face of nature’s fury, a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of our ancestors that continues to inspire and inform our understanding of human history.

But is there any other evidence that tornadoes hit Britain?

On 17th October 1091, London was hit by a vicious tornado.

The historical records describing the destruction wrought upon London, including the demolition of the wooden London Bridge, the devastation of 600 houses, and the severe damage to St. Mary-le-Bow church, underscore the formidable power of natural forces. The detail of rafters being driven six meters into the ground at St. Mary-le-Bow vividly illustrates the intensity of the event, likely a tornado, which also resulted in loss of life and widespread homelessness. This account provides a stark reminder of the vulnerability of even the most seemingly permanent human constructions to the whims of nature.

The enduring mystery surrounding Stonehenge, particularly the toppling of the gigantic Sarsen Trilithon Stones, invites a reconsideration of the forces capable of such feats. The traditional assumption that human intervention aimed at dismantling the monument falls short when considering the selective nature of the damage. The hypothesis of a tornado strike from the southwest offers a compelling alternative explanation, aligning with the directional pattern of damage observed at the site. The fact that only one pair of the trilithons was felled, while the rest of the monument remained relatively intact, suggests an event that combined immense power with precise directionality, characteristics emblematic of tornadoes.

Tornadoes, though not commonly associated with Britain’s climate in popular imagination, are indeed a part of the British weather landscape, albeit on a smaller scale compared to regions like the United States. The potential for a tornado to have caused the specific pattern of destruction observed at Stonehenge challenges preconceived notions about the stability of such ancient structures and the range of natural disasters capable of affecting them throughout history.

The observation made by Stukeley in the 16th century and the subsequent ‘repairs’ in the turn of the last century underscore the ongoing interaction between human efforts to preserve or restore ancient monuments and the natural processes that continue to shape them. This dynamic interplay highlights the fragility of our cultural heritage and the importance of understanding the various factors, both human and natural, that have influenced these iconic structures over millennia.

In exploring the possibility of tornadoes impacting Stonehenge, we are reminded of the broader implications of climate and environmental forces on archaeological sites. Such considerations not only enrich our understanding of the past but also inform preservation strategies for safeguarding our cultural heritage against future natural events. The case of Stonehenge serves as a poignant example of the complex relationship between human history, natural phenomena, and the ongoing efforts to interpret and preserve the legacies of ancient civilizations in the face of nature’s capricious power.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?