Section N – NY87SE

Contents

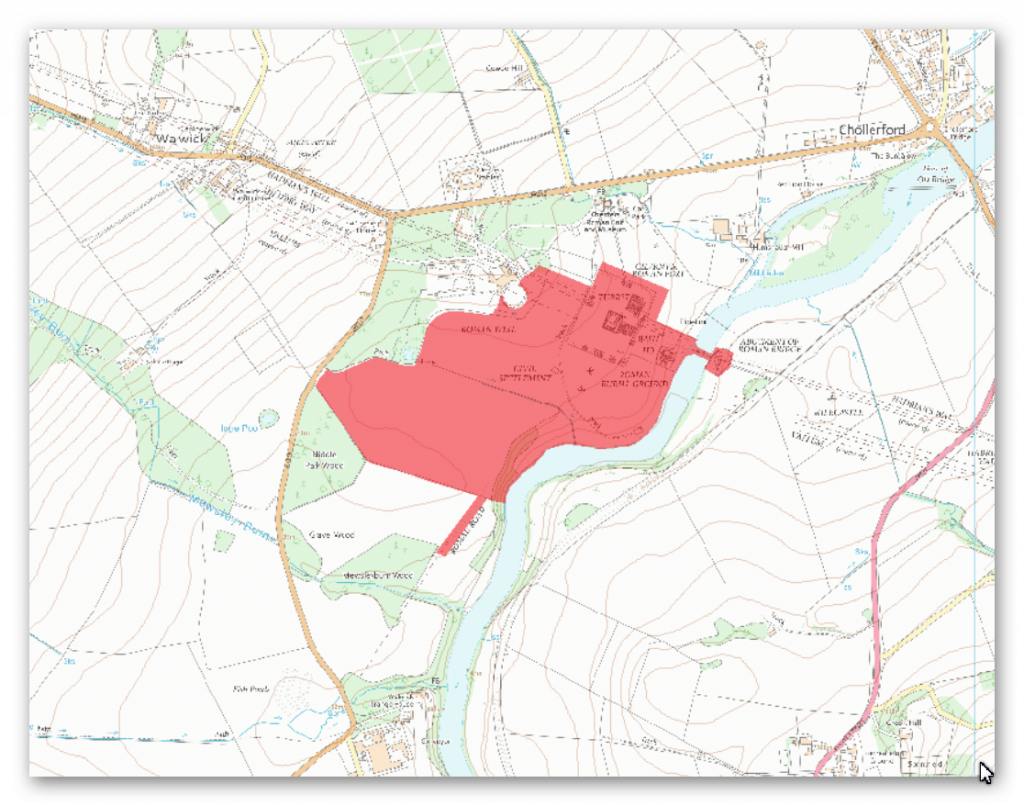

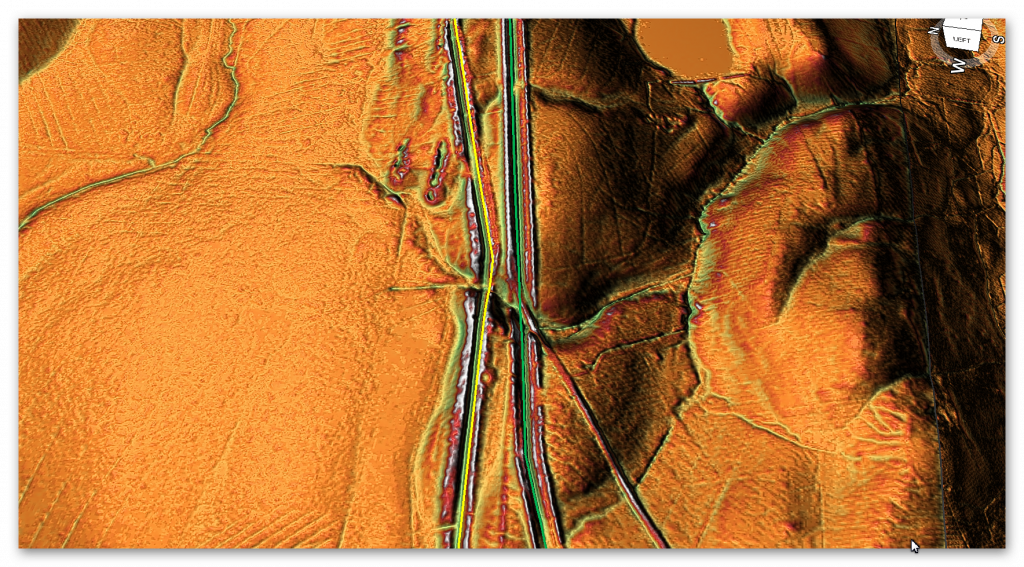

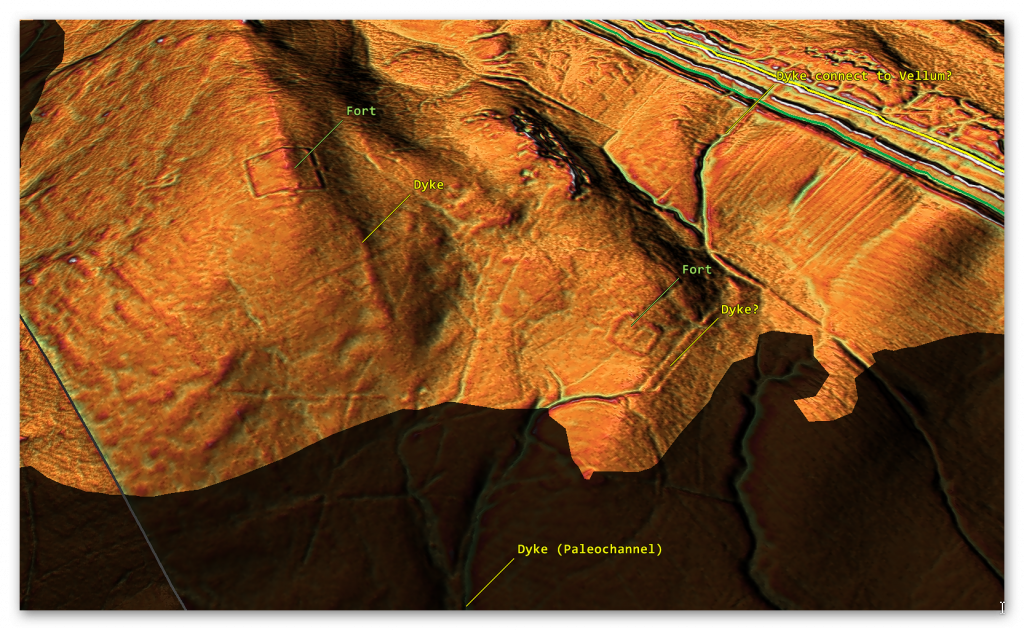

Section N – NY87SE – this is a section of Hadrian’s Wall showing the LiDAR, Google Earth and 1800 Maps of the Area covered by Historic England

Historic England Sections:

Name: Name: Hadrian’s Wall at Chesters and the field boundary west of Coventina’s Well in wall mile 27, 28, 29, 30 and 31

List UID: 1015914, 1010961, 1010960, 1010959

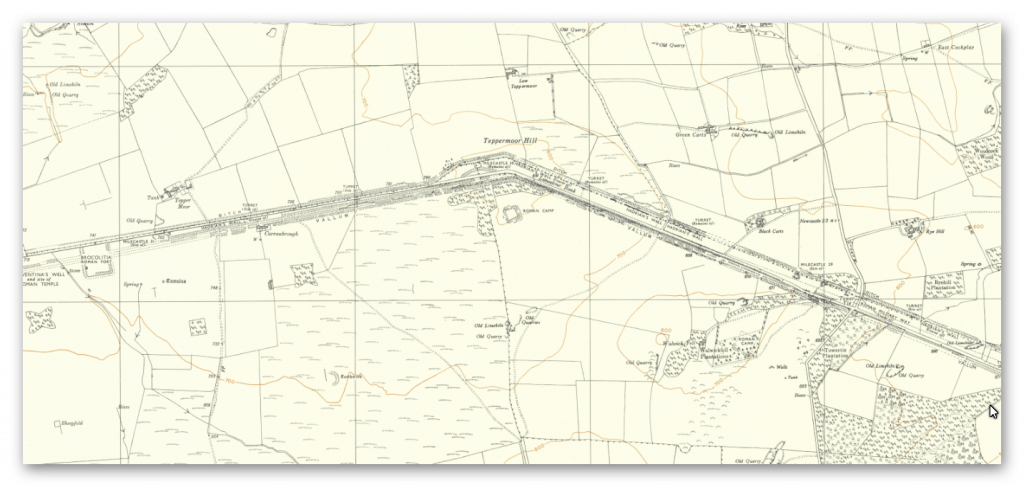

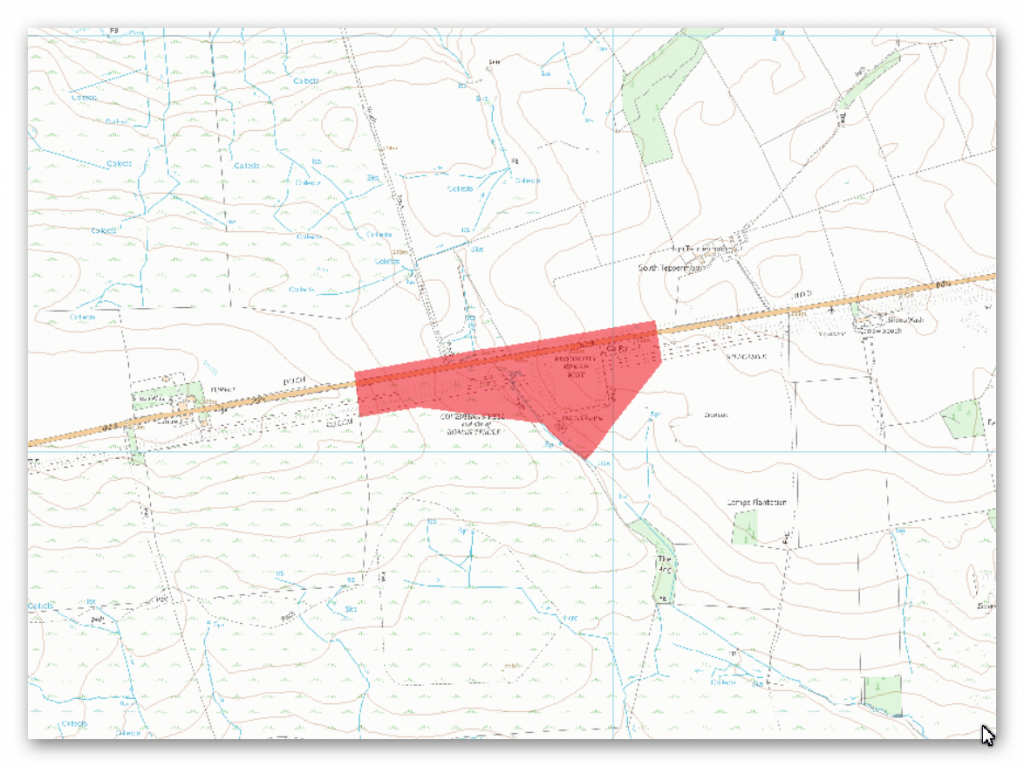

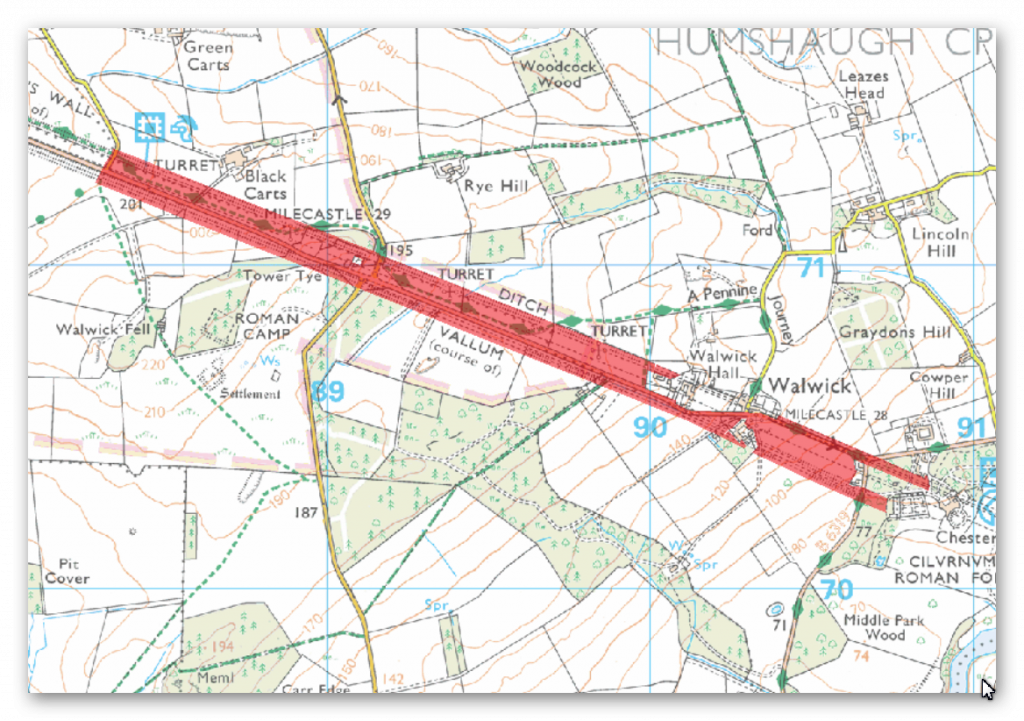

Old OS Map

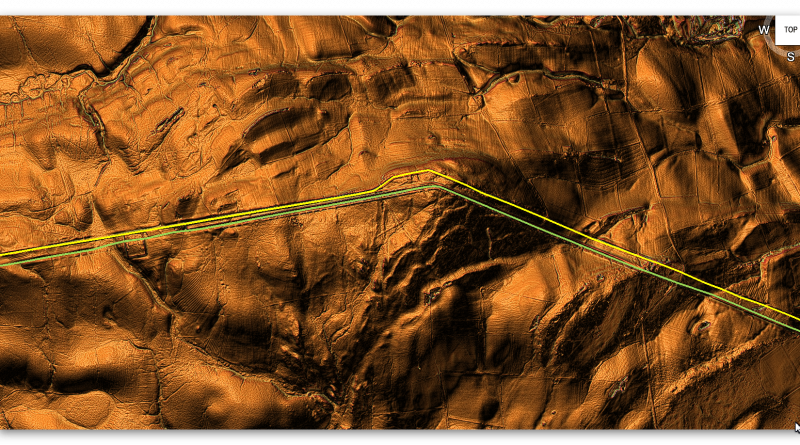

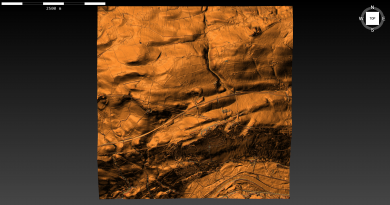

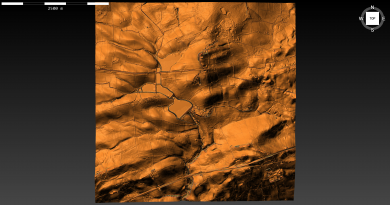

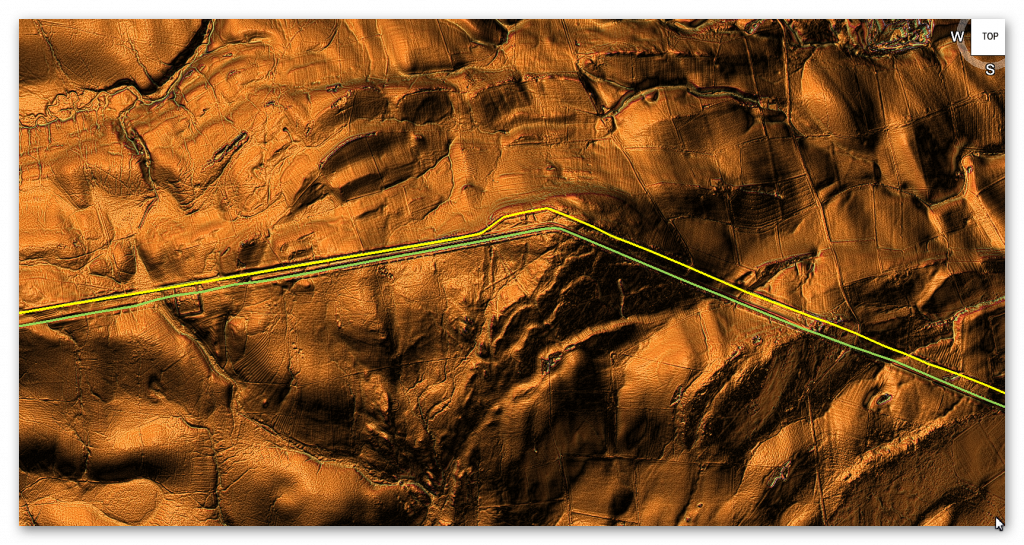

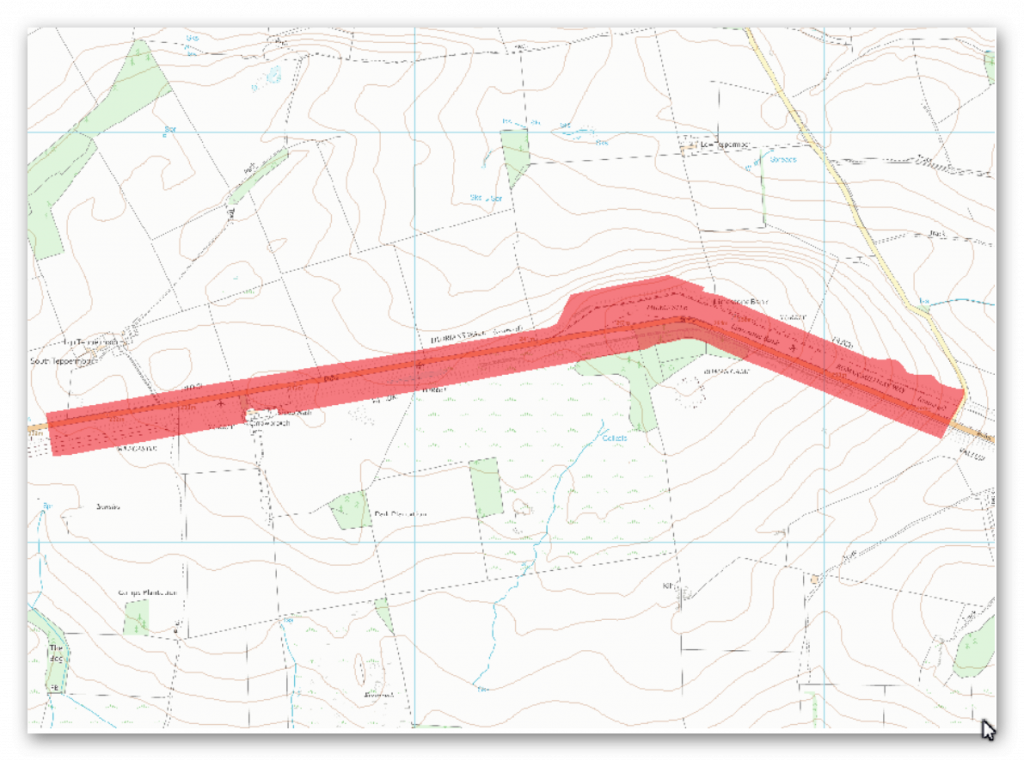

LiDAR Map

Google Earth Map

Historic England Scheduled Monuments within Section N

Name: Carrawburgh Roman fort and Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between the field boundary east of the fort and the field boundary west of Coventina’s Well in wall mile 31

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1015914

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between the road to Simonburn and the field boundary east of Carrawburgh car park in wall miles 29, 30 and 31

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010961

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between Chesters and the road to Simonburn in wall miles 27, 28 and 29

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010960

Name: The Roman fort, vicus, bridge abutments and associated remains of Hadrian’s Wall at Chesters in wall mile 27

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010959

The monument includes the Roman fort at Carrawburgh and the section of Hadrian’s Wall between the field boundary east of Carrawburgh car park in the east and the field boundary west of Coventina’s Well in the west.

The upstanding remains of Hadrian’s Wall from the field boundary east of the fort to the road junction west of Coventina’s Well are Listed Grade I. This section of Wall is situated in the shallow dip occupied by Meggie’s Dene Burn. The Wall survives below the course of the B6318 road throughout this section. The wall ditch survives well as a visible earthwork on the north side of the road. It averages about 1m deep, though it attains a maximum depth of 3m in places. The upcast from the ditch, otherwise known as the glacis, survives well in this section as a broad low mound to the north of the ditch. The precise location of turret 31a has not yet been confirmed as there are no upstanding remains visible above ground. However, on the basis of the usual spacing it is expected to be located about 270m west of Carrawburgh fort, beneath the surface of the B6318 road.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, is known for part of this section. It is visible as a low turf covered causeway immediately south of the car park heading directly for the east gate of the fort, though it fades before it reaches the fort. On the west side of the fort it re-emerges heading from the west gateway to the north mound of the vallum which was used to carry the road in this section. The road is visible as a low linear mound, 0.2m high, along the summit of the north mound of the vallum. The vallum survives as an intermittent earthwork throughout this section.

The vallum predates the fort at Carrawburgh as it was levelled to make way for the fort leaving no surface trace of the vallum in this area. To the west of the fort the vallum survives as a series of earthworks which have been reduced by later cultivation. The ditch averages 0.8m in depth, while the north mound of the vallum is visible as a low mound.

The fort at Carrawburgh, known to the Romans as Brocolitia, occupies a slight terrace on an otherwise gentle east facing slope, 650m west of the modern farm of Carrawbrough. The fields to the south and east of the fort are in the care of the Secretary of State. The fort is well preserved below the turf cover and its walls are believed to stand to around 1.5m in height. It measures 139.5m north-south by 109m east-west and encloses an area of 1.4ha. The defences consisted of a wall, 1.7m thick, backed by an earthen rampart with at least two external ditches in its earlier phases. Excavation of the headquarters building showed that the vallum had been levelled and its ditch filled in and the fort placed on top, demonstrating that the fort was added to the frontier system after the Wall and vallum had been constructed.

The fort was built for a cohort 500 strong, possibly part mounted. The civil settlement, or vicus, is located outside the fort to the south and west. It survives well as a series of earthworks and buried features. On the west side of the fort six terraces with scarps up to 2.1m high have been cut into the slope, parallel with the wall of the fort. Like the interior buildings of the fort, the stone buildings in the vicus have suffered from stone robbing. A bath house was discovered outside the fort and was excavated by Tailford on behalf of John Clayton during the 1870s. It had a layout similar to the Chesters bath house, though it was smaller in size. The excavation report indicates that it was radically reconstructed, probably during the fourth century AD. The location of the baths was not recorded in detail and so now its position is not known with certainty.

However, a platform to the south of the fort has been scooped out of a terrace close to the water level of the burn. The measurements of the bath house as excavated by Tailford would fit exactly into these earthworks. A paved road, 3.5m wide, was located in 1977 leading up to this platform from the burn. A shrine to a water-goddess known as Coventina was located and excavated by Tailford in the late 1870s. It was situated to the west of the fort at the source of a spring. The spring was encased in a rectangular stone basin about 2.6m by 2.4m. This basin was located at the centre of a walled enclosure, or temple, measuring 12.2m north-south by 11.6m east-west. A well, 2.1m deep and lined with masonry, is situated in the shrine. When excavated its contents included at least 13,487 coins, ten altars, a relief of three water-nymphs, the head of a male statue, two dedication slabs to the goddess Coventina, two clay incense burners and a wide range of votive offerings. Coventina’s Well can be seen enclosed by a fence to the west of the field wall on the west side of the fort. A temple to the god Mithras, more commonly known as a Mithraeum, was discovered during the dry summer of 1949. It was excavated in the following year by Richmond and Gillam. It has since been consolidated and is now displayed in its fourth century AD form, using cement replicas of the altars and statuettes and representations of interwoven timber wattle. It survives well as an upstanding stone structure, and is in the care of the Secretary of State.

The original altars and statuettes form part of a full size reconstruction of the temple located in the Museum of Antiquities at Newcastle Upon Tyne. When the Mithraeum was excavated Roman timbers were discovered in- situ due to the waterlogged conditions. Five phases of construction were able to be identified in the well preserved remains. Immediately outside the door of the Mithraeum was a small shrine now known as the `Temple of the Nymphs’. This feature was excavated during 1960 by Smith. Its remains included an altar, a spring/well, a paved area and an apsidal structure with a bench and short wing walls. This small temple was open to the sky. There are no upstanding remains visible on the surface except for the top of the north slab of the well-head. A cemetery is known to be situated on the east side of the fort. Lingard noted in 1807 that bones had been found between the fort and milecastle 31. Ten years later Hodgson learnt that urned cremations had been found during the quarrying to the east of the fort. Five tombstones have been recovered from Carrawburgh though their original positions are unknown. Excavations during 1964, in advance of the construction of the car park, revealed fragmentary remains of two buildings, one of which was identified as a small temple or funerary monument.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and associated features between the minor road to Simonburn in the east and the field boundary to the east of Carrawburgh car park in the west.

This section of the Wall follows an alignment straight from the North Tyne to the high point at Limestone Corner where it changes to a more westerly direction and occupies the gentle west facing slope all the way to Carrawburgh. There are good views to the north and south all along this section, and in particular from Limestone Corner. All the upstanding remains of Hadrian’s Wall, the milecastles and turrets in this scheduling are Listed Grade I.

The Wall survives as a buried feature for most of this section, except for the two well preserved sections west of the minor road to Simonburn. The two upstanding sections of Wall are consolidated and in the care of the Secretary of State. The east section is about 122m long and reaches a maximum height of 1.8m. The west section is about 48m in length and slightly lower. Elsewhere the Wall is visible as a low stony bank with a maximum height of 1m, or as a trench with spoil heaps either side of it. These trenches are the result of excavation in 1951 to either side of milecastle 30, when it was shown that the Wall in this section was narrow wall on a broad wall foundation. Beyond Limestone Corner the line of the Wall is overlain by the B6318 road and there are no upstanding remains visible. The outer ditch survives well throughout this section and averages over 2m deep.

The ditch is most impressive at Limestone Corner where it has been cut through the bedrock to a maximum depth of 2.8m. To the east of Limestone Corner the rock-cut ditch was left unfinished. The upcast mound from the ditch, known as the glacis, survives intermittently throughout this section. It is best preserved west of Limestone Corner where it attains a height of 2.7m. Milecastle 30 is situated on the high ground of Limestone Corner with commanding views in all directions. It survives as a turf covered platform up to 0.8m high. Excavation by Simpson during 1927 showed that it measured 20.2m from north to south. Part of the east wall is upstanding, measuring 3.1m long and 0.6m high.

The Military Way survives as a turf covered causeway leading up to the south gateway of the milecastle. Milecastle 31 is situated immediately to the east of Carrawburgh car park with wide views to the north and south, but with a restricted outlook to the east and west. It survives as a low turf covered platform 0.25m high. The remains of north wall of the milecastle lies beneath the B6318 road. Traces of the road connecting the milecastle to the Military Way survive as a causeway 0.15m high. Turret 29b survives as a turf covered mound with parts of the north, west and east walls surviving up to two courses. The road connecting the turret to the Military Way is discernible as a slight linear mound.

It was excavated during 1912 by Newbold who found the doorway in the east end of the south side and a ladder platform in the south west corner. Heavily burnt masonry and rubbish indicated that the turret had been destroyed by fire and was then left in ruins. Turret 30a is situated about 400m east of Carrawbrough Farm below the B6318 road. It was located during 1912, though there are no surface remains visible now. Turret 30b is located about 50m west of the drive to Carrawbrough Farm partly below the B6318 road. The south side of the turret is visible in the field to the south of the road as a turf covered scarp, 0.5m high.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is not known with certainty for most of this section. However, according to the observations of Horsley made in the 1730s and trial excavations by Newbold in the early 1900s, it is generally considered that the Military Way overlay the north mound of the vallum for most of this section. Further excavations in 1911 confirmed this interpretation. For this reason it is believed that the B6318 road overlies it between Chesters and Limestone Corner. At Limestone Corner the Military Way is visible as a low causeway, 0.6m high, leading to the south gateway of milecastle 30. Beyond the milecastle it rejoins the north mound of the well preserved vallum. Excavations during 1911 confirmed this to be the case.

The vallum is very well preserved throughout this section. It survives as a series of upstanding earthworks and an impressive rock cut ditch around Limestone Corner. The north mound averages 1.2m for most of its length where it is not overlain by the B6318. The south mound averages about 1m in height with crossings identifiable about every 42m. The ditch is mainly rock cut in the east half of this section with sheer sides and depths of up to 3.5m. In the west half of this section the ditch also survives well and averages 1.9m in depth.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and associated features between Chesters in the east and the minor road to Simonburn in the west. This section of the corridor occupies the steep valley side on the west bank of the North Tyne.

Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature below grassland for most of this section. However, it is visible intermittently as an upstanding feature in two places. In the grounds of Chesters house a short section of Wall, 13.5m long and up to 1.1m high, is exposed. Further west near Black Carts there is a section of consolidated Wall about 140m long. The south face averages 1.2m in height and the north face 1.9m. Turret 29a is located along this section of Wall. The length of Wall near Black Carts and the turret are in the care of the Secretary of State.

The wall ditch survives intermittently as a well preserved feature throughout this section. There is little trace of it above ground through the gardens of Chesters house, however it will survive as a buried feature. At Walwick, houses and gardens have been built over the line of the Wall. Beyond Walwick the ditch is visible on the ground as a depression partly overgrown by scrub and small trees. It averages about 1.7m in depth, though it reaches a maximum of 3.1m in places. The upcast mound from the ditch, known as the glacis, has been mostly ploughed out. However, it does survive well east of milecastle 29 where it reaches a height of 3.5m. The exact location of milecastle 28 is not yet confirmed.

The scarp cited as being part of the milecastle platform by the Ordnance Survey is too far south of the line of the Wall and looks to be early modern in date. The predicted location, based on the usual spacing, would be where the B6318 changes direction as it enters Walwick from the east. Milecastle 29, or Tower Tye, survives as a series of clearly defined robber trenches on all sides. According to Hodgson, who investigated the milecastle during 1840, the dimensions were found to be 50.4m north-south by 46.4m east-west. As at milecastle 25 there are traces of an external ditch. The remains of the milecastle are buried below grassland. The precise location of turret 27b has not yet been confirmed. However, its predicted location, on the basis of the usual spacing, is in the grounds of Chesters house. It may survive as a buried feature.

Similarly the precise location of turret 28a has not yet been confirmed. However, its predicted location, on the basis of the usual spacing, is about 250m west of Archway Cottage near Walwick Hall. It is considered to survive as a buried feature below the grassland. Again the precise location of turret 28b has not yet been confirmed, though it is expected to be positioned about 225m east of the road which runs north to join the B6320. This turret is also considered to survive as a buried feature below the grassland. Turret 29a, or Black Carts, survives well as an upstanding feature. It is located about 100m east of the minor road to Simonburn with wide views to the north, east and south. It was excavated in 1873 and again in 1971 before it was consolidated. Internally the turret measures 3.45m by 3.4m and is of a type thought to have been built by the twentieth legion. The turret is in the care of the Secretary of State along with the section of narrow wall which abuts the broad wall wings of the turret on both sides.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is not yet known with certainty. It does not survive as a feature visible on the ground.

However, according to Horsley writing in 1732, the Military Way in this section followed the line of the north mound of the vallum except for where it veered towards milecastles. The present B6318 road overlies the north mound of the vallum, and therefore remains of the Military Way may survive below the modern surface.

The vallum is visible as an upstanding earthwork throughout much of this section, though in the stretch between Chesters and Towertie Plantation it has been largely ploughed out. Beyond Walwick the north mound of the vallum is overlain by the B6318 road. Here the vallum ditch averages between 1.5m and 2m in depth while the south mound averages about 2m in height except for where it has been reduced by ploughing.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and associated features from the bridge abutment on the east bank of the River North Tyne in the east to the woodland on the east side of the Chesters property in the west.

This section of frontier, which includes Chesters fort (known to the Romans as Cilurnum) occupies a broad stretch of river terrace on the west bank of the North Tyne. The Wall is visible intermittently as an upstanding feature in this section. Short sections of Wall are upstanding at the junctions with the fort on the south sides of the east and west gateways. There is a 6.7m length of consolidated Wall to the east of the fort which is in the care of the Secretary of State. West of the fort the Wall line is denoted by an amorphous, discontinuous mound up to 0.4m in height. There are no visible upstanding remains west of the ha-ha (sunken wall), which forms an element of the landscape gardens of Chester House. The wall ditch is discernible to the east of the fort as a ploughed down upcast scarp. For the most part it survives as a silted up feature below the surface.

To the west of the fort the ditch survives as a discontinuous depression, 0.3m deep. Turret 27a which occupied part of the site before the fort was built was discovered by excavation during 1945. It was found to lie about 42m west of the inner face of the east gateway. The bridge abutments and piers which carried the Wall and Military Way over the River North Tyne survive well as upstanding monuments.

There is also a section of consolidated Wall and tower base adjoining the east bridge abutment on its west side. Excavations of the abutments by Bidwell and Holbrook during 1990 have shown that there were two clear phases to the bridge; the early Hadrianic structure and the larger and more imposing one of third century AD. The precise location of the vallum around Chesters has not yet been confirmed. Aerial photographs show the possible start of it from near the west bank of the North Tyne, but around the fort the course is conjectural.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, survives well in the section between the North Tyne and the fort. The line of the road is clearly defined on the ground leaving the fort by the east gateway and heading towards the Roman bridge. Initially it is a depression and then becomes a causeway with a maximum height of 0.8m with a kerb to the south visible for 1.3m. There are no upstanding remains of the road to the west of the fort. However, the antiquarian Horsley considered that the Military Way exited Chesters and then converged gradually with the north mound of the vallum where they continued united for a considerable distance.

The Roman fort at Chesters, which is in the care of the Secretary of State, was built to guard the North Tyne crossing of the Wall. Excavation has demonstrated that the fort was constructed after, and overlies, the Wall. It encloses an area of 2.1ha. The fort wall is exposed in a number of places round the circuit. Elsewhere the outline of the fort is shown by a scarp which survives to a maximum height of about 2m. The upstanding masonry is best preserved in the south east corner where it survives to a height of 1.9m. Well preserved visible remains in the interior include the consolidated remains of the headquarters building, commanding officer’s house and some barrack blocks.

Buried remains will survive below the ridge and furrow cultivation inside the fort. The site has been excavated at various times from 1796 up to the most recent investigations during 1990-91. Extensive amorphous earthworks within the fort probably show the position of the backfilled trenches and spoil heaps, resulting from the various excavations. An extensive civil settlement, or vicus, is located outside the fort on the south side. It occupies an area of level ground bordered to the east by the steep cliff down to the river’s edge. Its buildings and roads are known largely from the evidence of aerial photographs. The settlement is orientated around the road leading south from the fort and a road which bisects it at right angles. A well, believed to be Roman, survives as an upstanding feature immediately outside the garden of Chesters house. The well preserved remains of a bath house are visible to the east of the fort about 30m uphill from the present course of the river. It had a paved floor, hypocaust and an outflow drain, as well as various hot and cold rooms.

An interesting and unique feature of this bath house is that when it was discovered in the 1880s the remains of 33 human skeletons, two horses and a dog were found. There is a however some doubt as to exactly where around the bath house they were found. A quantity of monumental masonry has been found by the river at the point where the ha-ha wall joins its bank, suggesting that this was the location of the cemetery. More recently an altar has been found in the river bank closer to the fort together with a fragment of architectural masonry. A road runs from the south gateway of the fort to the Stanegate Roman road which lies further south. Aerial photography has shown that this road runs along the crest of the river bank south of the ha-ha wall.

Investigation

The Vallum in this section changes course to follow the Wall alignment (or vice-versa?) The road that was constructed on the bank of the Vallum in the previous section – now branches out over the countryside separate to the vallum and then on this section again reconnects and the road is the one of the Vallum banks. Military way is seen to also connect to the same bank as the road suggesting that (the road) was also originally roman constructed after both the Vallum and Military Way?.

Another interesting feature is the location of the two ‘Roman temporary forts’ – these are not connected to any road system although they are close to the Wall and Vallum – but a paleochannel seems to connect both ‘forts’ but also runs from the Vallum. The larger camp is called ‘Brown Dikes’ – no doubt because it was on Brown’s moor and is connected to each other by a ‘dike’?

To understand the problem with Hadrian’s Walls history read our article HERE.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.