Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

Extract from the book: The Stonehenge Enigma

Woodhenge has a series of ‘massive’ wooden post holes – at this point, I need to explain that archaeologists don’t seem to understand the difference between a ‘Post Hole’ and a ‘Stake Hole’. You use stake holes for posts such as fences as they can be easily buried in the ground as they have a sharp point – this point naturally compresses the surroundings (due to the shape and hammering from above) so they don’t move or wobble – this is key to understand the Woodhenge reconstruction.

A ‘Post Hole’ is totally different as it has a flat bottom and needs rubble to stop it rocking from side to side. Stake holes are easy as they are ‘self-burying’ while post holes are more work as you need to dig a hole for it. The only reason you would do all the extra work of digging a flat bottomed hole (especially in chalk) is if the wooden pole is to take some kind of weight from above, for a stake hole is useless for this type of structure as it would sink (overtime) under the weight pushing down on the point and probably fall over.

Therefore, if you have a round wooden single-storey building with a simple roof as current archaeologists suggested for some of these post hole structures, why use these massive posts as it is ‘over-engineering’ and time consuming – especially with simple tools?

Cunnington excavations at Woodhenge in 1929, suggested that some posts are up to 60 inches in diameter:

“clear evidence was obtained in excavation that the six centric rings of holes once held posts or tree trunks varying from 1ft to 3ft in diameter according to the size of the hole…… the size and depth and distance varies in each circle…. In the outer circle holes are 6ft apart from centre to centre, from 1 1/2 ft to 2ft in depth and from 2ft to 3ft in diameter. In the second circle the holes are larger and further apart, averaging about 4ft in depth and 3 ½ to 4ft in diameter. The largest of all were those were those of the third circle, being about 6ft deep with a diameter at the top from 4ft to 5ft “ (Cunnington. M.E., ‘Prehistoric Timer Circles’, Antiquity A Quarterly Review Of Archaeology Vol.1, 1927).

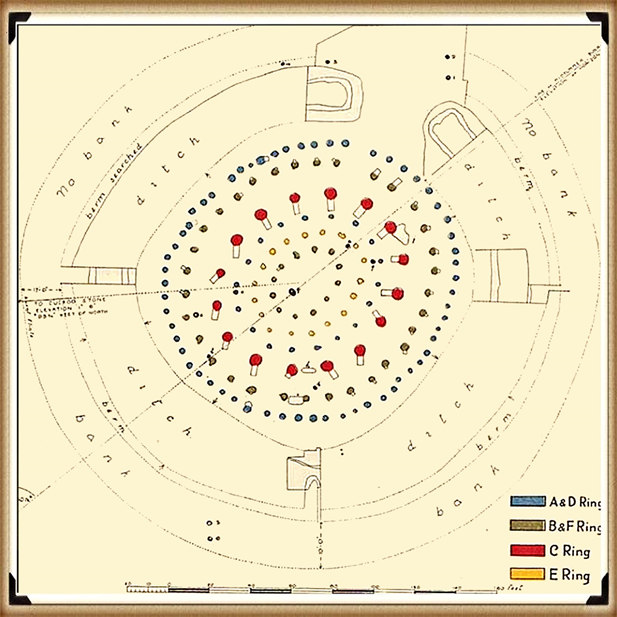

| Figure 59– Cunnington Excavation plan 1929 |

Sadly, Woodhenge reconstruction shows us yet another illustration of flawed science in archaeology. Even with a ‘second rate’ excavation report from the 1920’s the conclusion of modern archaeologists is that this structure was a single-story house – a slightly grander feature to the traditional ‘iron age’ house. This is simply nonsense. If we look closely at the evidence presented here, we obtain a totally different and more accurate conclusion to the nature of this structure.

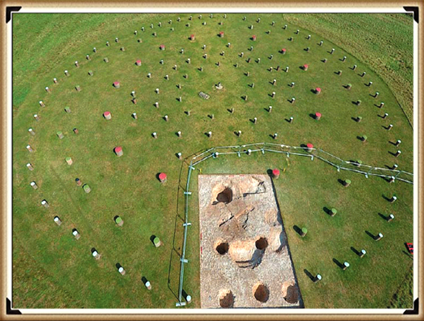

Firstly, if we look at the layout of the site (which lacks much detail), we can see from these original excavation plans the scale of this understatement, as the existing ‘concrete’ posts, on the site, are far too small. The most recent photo was from the excavation by Pollard in 2007, indicates that these posts are at least five times larger than the current representations.

The next fact that goes unanswered is the reason for the large ramps by the post holes. You don’t take time to put 32 ramps into the soil unless it is essential as you just added at least another month to the building work for the site and 500 working-hours. What archaeologists have missed (or failed to mention) is in which direction these ramps were cut – as it tells us more than the entire excavation report by Cunnington.

The massive 4 – 5 ft pine posts of the 16 postholes (known as the C Ring) would weigh 214kg per foot of length. Therefore, a sizeable healthy person (we will go into detail who these megalithic people are and where they came from in the next book of the series – ‘Dawn of the Lost Civilisation’) could pick up one foot of pine and place it in a hole without assistance or a need for a ramp.

| Figure 60 – Woodhenge reconstruction – post holes much larger than the concrete posts on the site! |

Consequently, an eight-foot pine tree trunk could easily be placed on the shoulders of 8 people and put straight into the hole, which is the current estimations by archaeologists for a single storey structure. Therefore, the empirical evidence suggests they are wrong, and the pole was much more significant.

What we have seen at Stonehenge is similar ramps not by the 4-tonne bluestones but by the Sarsen stones that weighed an average of 25-tonnes (the trilithons are 35-tonnes) but half the size of these ramps.

A 25-tonne, pine post of width between 4 – 5 ft would be 39m long or 128ft, and a 35-tonne pine tree is some 177ft long. But do Pine trees grow that tall? Just down the road from Durrington Walls is Longleat Forest, within this forest there are pine trees like the Douglas fir that grow to nearly 200ft tall.

Moreover, the site plan does also give us another clue to the length of these poles. If to look carefully at the angle of the ramps into the giant postholes, you will notice that they are not all facing the same direction. The only logical reason for that to happen is if you erect the pine poles in a set order so that they would not hit or interfere with each other when attempting to erect the posts.

This allows us to come to some remarkable conclusions about the construction and the process of how it was built:

- Holes were filled in an anti-clockwise direction starting at hole 1 (at four o’clock to the site)

- Poles must have been more than 100’ long as otherwise, you could erect them in any order and direction.

- The ditch that is current at the site was added at a later date, as you would need to bring the poles through the ditch and in some cases be in the ditch to erect it.

- The 4 to 5ft diameter posts all entered the site from the south, as it has the minimal distance to travel – as these poles were either rolled or dragged on a sledge and therefore probably the direction of where the pine trees have initially been growing or unloaded, after being floated down the river.

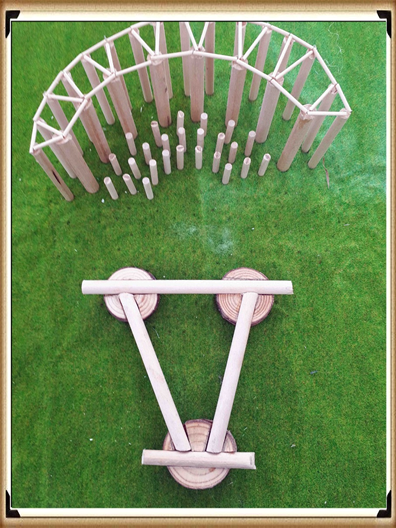

Now the slopes for ‘Ring C’ (the largest posts) are 5 to 8ft long, which are even longer than the Stone ramps (3 to 4ft) at Stonehenge (Fig.58). This probably shows the large (Sarsens are only 13ft tall) leverage factor required to be pulled upright with an A-frame, which then allows the posts to slide into position and then into the hole.

Ring B – the 3.5 to 4ft diameter trees, also have ramps, but much smaller (3 to 4ft), indicating less leverage and therefore half the weight/height? Moreover, they were placed into position after the C Ring, as their ramps point away from the centre with no common direction.

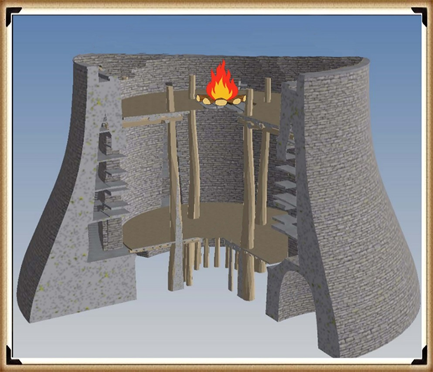

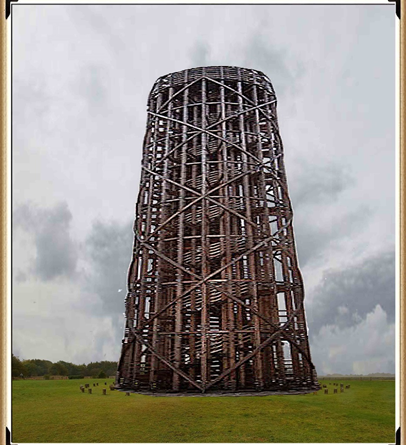

| Figure 61– Broch which was a later version of Woodhenge – made of Stone |

The last row of postholes (A), 1 to 3ft in diameter, do not have ramps and are sporadic in nature and size – which leads me to believe they have no structural significance and was probably more like a palisade covering, to either enclose the structure or allow mud or reed covering (wattle & daub) and protection from the elements.

The internal posts (D to F) are superficial and probably were there to support the first-floor structure, as we see in their successors in British history the ‘broch’ – a stone version-built thousands of years later for the same purpose.

But my money would be on the tower being of a lower ratio of 1 to 1, with the base, making it 135ft high and the same height as Silbury Hill, a little further up the river Avon and its design I would suggest, would have been the same ‘layer cake’ design as we will see in the chapter on Avebury.

Therefore, what would you build next to a harbour to attract and direct boats – obvious isn’t it, a fire beacon (with a stone base) as we know from written history and the Pharos of Alexandria (280 – 247 BCE).

| Figure 62- Woodhenge reconstruction – probably looked like during phase I of its construction, with a spiral staircase. |

Furthermore, this link with the harbour is illustrated by the construction of the Moat, Bank and then a Dyke. As we have suggested, the Woodhenge ditch would not have existed at the original time (Phase I) of the construction of the C and then the B rings. It seems that it was added at the end of Phase I when the structure was complete and before Ring A was established, as it points to the shoreline of the Neolithic Avon River. This alignment disproves the current ‘expert’ theory about being an astronomical alignment with the Solstice Sunrise.

Evidence for the construction of the postholes (with gaps in the circle which were later filled with smaller posts) indicate that the ditch had filled from age, or by design. The main opening (in the A circle) to the northeast is not in line with the gap in the ditch, and the two other spaces in the circle, would track across the ditch in the southeast and northwest.

As for the dating of Woodhenge reconstruction (and Durrington Walls), like Stonehenge, unrelated antler and bone fragments have dated it to about 2400 BCE, which is very convenient. The problem is that most of the post hole samples at Woodhenge were either lost or have been stored away and not tested since the excavations between 1926 to 29, for reasons known best to the experts.

Moreover, like the samples taken from the old car park in 1966, pine charcoal were reported to be found “similar to the charcoal found at Woodhenge” was the quote from the labs at the time, who failed to carbon date the samples as the experts had declared them Neolithic, supporting the antler pick dates. Although now, once this gross error was exposed, we know these pine charcoal wood dates to be in fact Mesolithic 8100 BCE – which ‘begs-the-question’ so are the pine charcoal dates found at Woodhenge also Mesolithic?

Less than a mile down the river is ‘Blick mead’, (Vespasian’s Camp),which has also been found dates ranging from 7900 BCE, (remember our bluestone estimation for Stonehenge is 8000 BCE), to 4050 BCE, with multiple RC dates from the 8th to the 5th BCE. Sadly, until someone finds these samples and carbon tests them, to get an accurate date for Woodhenge and Durrington Walls, this unscientific archaeological ad hoc dating methodology will continue.

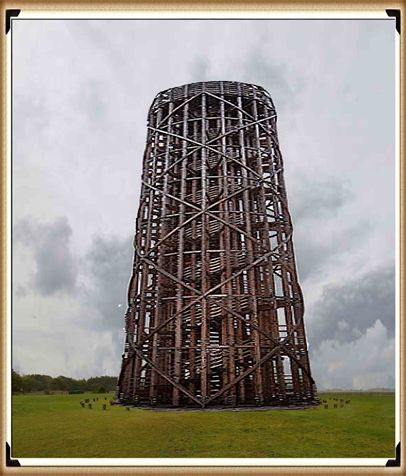

| Figure 63- Woodhenge Reconstruction – Unique building technique for towers – still used today |

Furthermore, the engineering structure created by this civilisation – like the design at Stonehenge, has been overlooked by archaeologists looking for a more simplistic ‘hunter gatherer’ solution for this superstructure, which has ended up with a single storey roof, that is clearly well over engineered for that purpose. What we can see at Woodhenge (and also at The Sanctuary at Avebury) is the ‘triangulation’ of wood joints using the mortice and tenon techniques we have seen on the Sarsen stones at Stonehenge – this structural technique (which are incorporated in modern towers today) allows to construction of extremely high wooden towers, which is what we see through the Woodhenge reconstruction.

The video on Woodhenge reconstruction is available from: https://youtu.be/piow4yDUs3U

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Pingback: Archaeological 'pulp fiction' - has archaeology turned from science? -

Pingback: Archaeological 'pulp fiction' - has archaeology turned from science? - Prehistoric Britain