The Stonehenge Avenue

Extract from the Book: The Stonehenge Enigma (The Stonehenge Avenue)

When the waters started to subside, the builders of Stonehenge had an engineering problem: how to cope with the lower groundwater table, to allow the Stonehenge moat to remain full. Firstly, as we have already illustrated, by lining the Stonehenge moat with a clay waterproofing, so it acted like a dew pond, and in this chapter we shall go into detail of how they built a new earthwork called ‘The Avenue’ (Stonehenge Avenue) with its own moat which brought the waters closer to the monuments bathing moat.

Processional Walkway

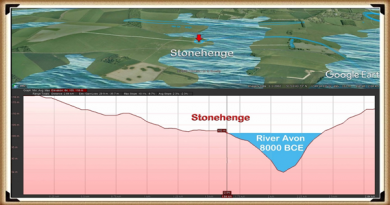

The Avenue was created sometime after the original moated henge, once the original Mesolithic groundwater and shoreline lowered towards the new Neolithic groundwater level. When the water levels fell, the builders faced two problems; firstly, the original mooring could no longer accept boats or cargo, so a new entrance was required. Secondly, the moat would no longer fill as it did in Mesolithic times, as the water table had dropped by about 10 metres.

As we have seen from the excavations by Hawley in the 1920s, the builders had added a liner similar to those found in other Mesolithic period constructions like ‘dew ponds’ also found in this area. The reason for the liner would have been to retain the water that accumulated by the natural rain and seasonal high tides that would have replenished the moat. It is entirely plausible that insufficient, or infrequently water levels were a common occurrence during the late Mesolithic, therefore if they wished to continue the bluestone treatments, an alternative method to fill the moat needed to be found.

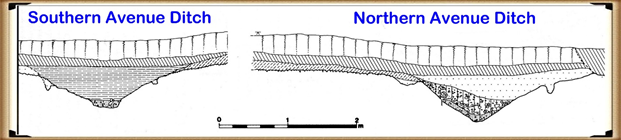

The Avenue is quite curious, and excavations have revealed its ongoing development, as indicated by the post holes dotted down its entire length. This clearly shows that it ‘adapted’ over a long period to match the retreating shoreline in the Neolithic period, which lasted over two and a half thousand years. Moreover, the physical construction of the Avenue earthwork shows the incorporation of water features. The Southern ditch is much shallower than the Northern ditch of the Avenue. This is because the water lies on the Southern side of the Avenue and does not need extra depth to fill the Southern ditch evenly, while the Northern ditch is further away from the water (and on a gradient). For it to fill evenly to the same depth of water as the Southern ditch, the Northern ditch would therefore need to be 10% deeper. Furthermore, this extra depth to one side of the monument can also be seen in the main ditch of Stonehenge as the main ditch corresponding to the northern avenue ditch is also 10% deeper.

Figure 31– North and South Avenue Ditch comparison

The wooden poles within the Avenue seem to be somewhat sporadic and impractical at first glance. But if you then add the prehistoric waters to the Avenue, you can see that the poles actually line up in pairs. These pairs of posts seem to appear every ten metres as you proceed down the Avenue, indicating that the Avenue was created in sections. This is a consequence of the periodic need to replacement of the poles as the shoreline retreated. The first main brace of these shoreline poles are seen quite close to the famous North-Eastern entrance by the Heel Stone, extending to the last evidence of the poles at the ‘elbow’ at the end.

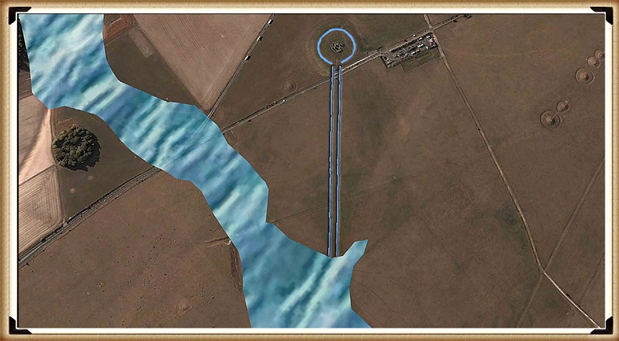

The current ‘expert’ theories suggest that the path of the Avenue is a processional walkway down to the River Avon. But a careful study of this walkway shows that it makes absolutely no sense in the route it follows – it’s not direct, nor logical in its course. What the avenue shows as we see today, is the continuation of its association with the River Avon, after the original Avenue that finished at Stonehenge Bottom had fallen into disuse. This explains the strange haphazard route it now shows. Archaeologists, not finding the valid reason for its course, attempt to justify the route as a ‘ceremonial’ pathway, which ignores the facts. These ‘facts’ are compounded as later ancestors constructed Barrows that mimicked their ancestor’s constructions and placed burials within them, totally confusing the timeline.

The later attempts to keep a connection to the original builders of Stonehenge can be seen in the Avenue as it moves off to the North East for about 500 metres (the original construction), then suddenly swings off East for another 1,000 metres, then turns again and heads South, like a stretched lower case ‘n’. Archaeologists suggest that this is a ‘natural route’ deliberately passing burial mounds that lay to the East of Stonehenge.

The facts are; the walkway came first, followed by the introduction of the burial mounds – which is borne out by carbon dating showing that the Avenue was first introduced in Neolithic times, and the burial mounds much later in the Iron Age. Also, archaeologists have identified that the Avenue was built in sections; the first section up to the ‘elbow’, according to Julian Richards in his book ‘The Stonehenge Environs Project’, was built during what archaeologists’ call ‘Period II’, including:

- Modification of the original enclosure

- Entrance

- Construction of the first straight stage of the Avenue

- Erection of the Station Stones

- Resetting of the two entrance stones

- Dismantling of the double bluestone circle

Our hypothesis (unlike the current expert views) answers this question fully. The Avenue was built to meet the new shoreline that emerged during the Neolithic period, where (as at the old North West entrance) they received and moored the boats, cargo, and even the stones. Consequently, this then acted as a new entrance to the Stonehenge monument.

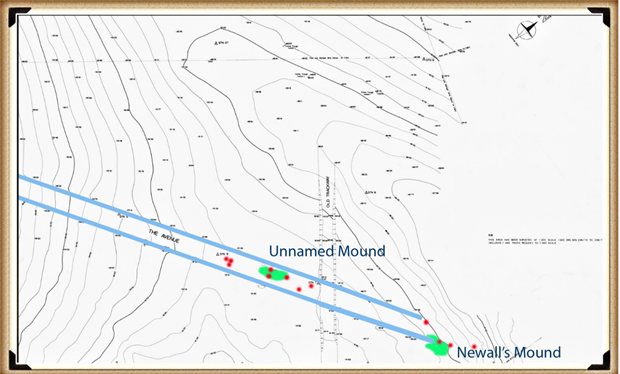

Further evidence of this shoreline can be seen in the post holes found in the Avenue. These post holes do not make sense, as they would have blocked the walkway unless they are mooring posts for various phases in the Avenue’s construction and water level. A small survey carried out from 1988 to 1990 investigated the last 100m of the Avenue up to the elbow. (Cleal et al., 1995) It found 14 large post holes that could have been used as moorings for boats. These moorings are paired off at 45 degrees to the Avenue, which would match the exact shoreline predicted over several periods.

| Figure 32– The Avenue showing its termination and the wooden post holes and man-made mounds that were used to unload ships and boats |

Recent investigations have revealed that as well as post holes down the Avenue, there is a distinctive man-made mound of ‘clay and flint’ called Newall’s mount (named after it’s discoverer) and a second mount, can also be found on the contour maps of the avenue (but has yet to be named or excavated), which has the same characteristics and post hole alignment. This indicates that these human-made mounds were used as raised platforms to unload boats as they could not serve any other practical purpose. (Stonehenge – the environment in the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age and a Beaker-Age burial, WANHS Magazine, 78, 1984, pp. 7-30)

NB. Such platforms are also found in the nearby site of Avebury, at a location I called Silbury Avenue, (which I discovered in 2014) and leads over Waden Hill, to a mooring platform called ‘Waden Mount’ located by photographer Pete Glastonbury in 2004. (Langdon, 2015, ‘Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue’)

We can also date the extension past the ‘elbow’, as it no longer has the elaborate moats on either side of the processional walkway. The Avenue beyond the ‘elbow’ travels over a series of hillocks that could not hold water at any level and therefore made such moats useless and unnecessary. This, again, shows that our ancestors were practical and pragmatic people who included aspects such as ditches for useful purposes, not for religious or aesthetic reasons as current archaeologists believe.

At this stage of the monument’s construction, I believe Stonehenge finally turned from being a monument to the moon, for curing the sick for excarnating the dead, to become a shrine to life and the sunrise – which was, in the Bronze Age and after that, taken over by a new civilisation of druids and iron age tribal cultures.

The Avenue II

An indication of the changes that were introduced in Phase II of Stonehenge can be seen in the development of the Avenue to maintain the ceremonial link between Stonehenge and the river system. Our ancestors started by backfilling the ditch in the North-East sector of the site. Both Hawley and Atkinson observed that the secondary filling was not natural. This backfill extended to a depth of 1 m, at which pottery and bluestone fragments are first seen, clearly indicating that it preceded the arrival of the bluestones.

When the Avenue was first constructed, it could have had a dual purpose: to serve as the new mooring processional way for the dead, and also to help maintain the groundwater levels, because the moat had been reduced to a trickle as a consequence of the lower river levels.

| Figure 33– The Avenue terminating at Stonehenge bottom showing the ditches on each side |

We have seen in the archaeological section of our hypothesis that Hawley had found a liner in the moat. This liner would not have been required when the moat was first constructed, as the groundwater tables were sufficiently high to fill the moat, whether daily or periodically. But a liner would have been necessary once the tidal groundwater no longer reached the base of the pits. To keep the moat waters at a suitable depth, the pits would have needed to be topped up from time to time with either groundwater from the receding rivers around Stonehenge, precipitation like dew ponds or manual transference (or a combination of all three).

The Avenue is a processional causeway that had a deep trench built into both sides (over 1m deep in places). This trench is totally unnecessary unless there is another reason for its use, and that reason was either practical or symbolic.

The ditch allows water to travel along the Avenue all the way up to the existing moat, but there is no evidence that it is directly connected – but it doesn’t need to be as we have already illustrated the fact that chalk is a porous material that will allow water to flow through it over short distances.

More information on Stonehenge Avenue can be found on our documentary video: https://youtu.be/-Ds1HYB15w8

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.