The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

Contents

Now been updated with more data here: – https://prehistoric-britain.co.uk/the-long-barrow-and-dolman-enigma

Dolmens, Long Barrows and Burial Passage misconceptions

As a discipline deeply intertwined with the humanities and sciences, archaeology faces unique challenges that can slow its progress compared to fields like engineering or medicine. Limited funding, the complex nature of archaeological evidence, and interdisciplinary hurdles complicate the timely update and correction of historical misconceptions. These issues are compounded by the need to respect contemporary cultural sensitivities and legal frameworks, which can delay excavations and complicate the interpretation of findings. Moreover, integrating transformative technologies such as GIS, LIDAR, and Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) into mainstream research is often slow, affecting how quickly new insights can revise outdated narratives.

These structural challenges in archaeology contribute to frequent misinterpretations and the misclassification of archaeological sites, which can persist even in the face of new evidence that suggests alternative explanations. The slow-moving nature of the peer-review process and the specialised language used in academic publications further widen the gap between current research and public understanding. Addressing these issues is crucial for refining our understanding of history and requires a concerted effort to enhance the dissemination of archaeological research and foster public engagement. Examples of misidentified sites and the consequences of such errors will highlight the critical need for improving both academic and public discourse in archaeology.

Prehistoric burial sites have been categorised and named differently across regions, including Ireland and Wales, based on their structural features, historical context, and cultural significance. Here’s a list of various terms used to describe these monuments:

General Terms

Barrow – A mound of earth and stones raised over a grave or graves.

Tumulus – Another term for a mound or barrow.

Cairn – A mound of stones built as a memorial or landmark, often used as a burial site.

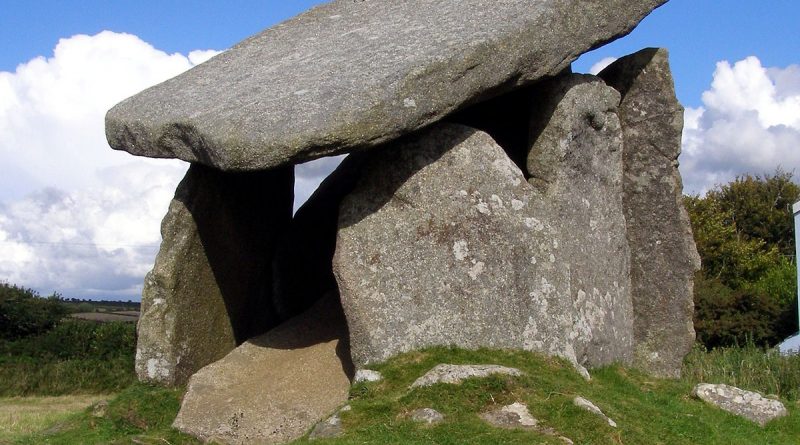

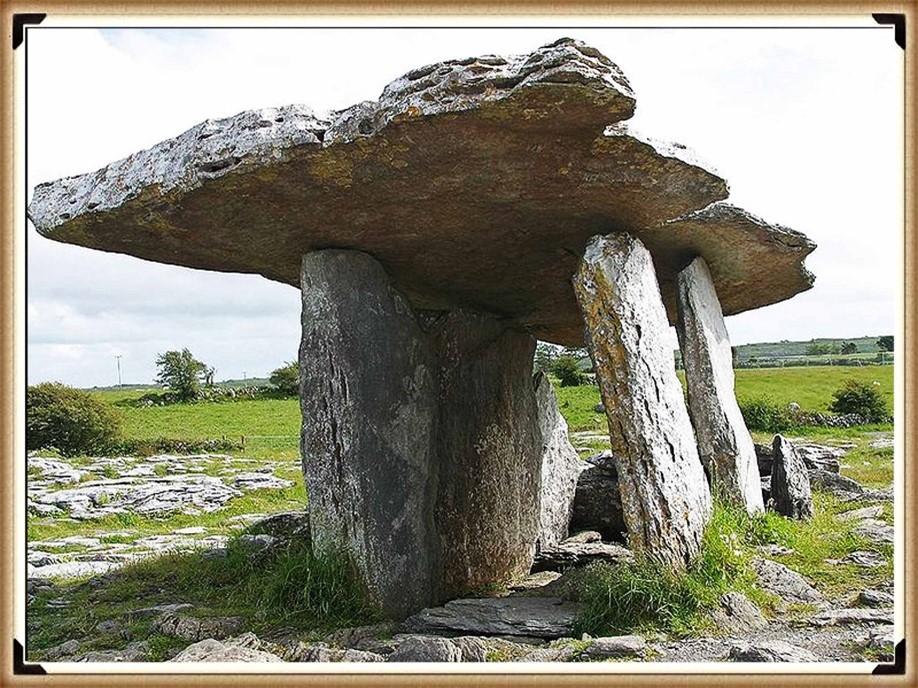

Dolmen – A type of single-chamber megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more vertical megaliths supporting a large, flat horizontal capstone (also known as a table).

Passage Tomb – A tomb with a passage leading to one or more burial chambers covered with earth or stone.

Chamber Tomb – A broad category that includes any tomb with an enclosed space that might be segmented into chambers.

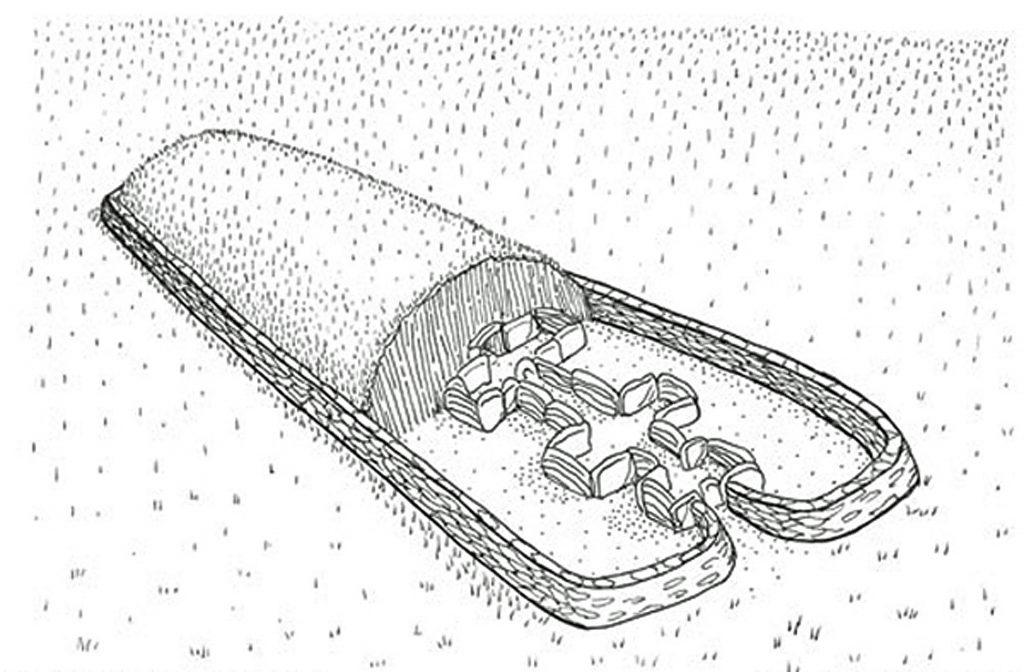

Long Barrow – A type of barrow that is notably longer than it is wide, often associated with collective burials.

Specific to Ireland

Court Tomb – Prehistoric tombs found in Northern

Ireland is characterised by an entrance court leading to a burial chamber.

Portal Tomb – Another term for dolmens in Ireland, distinguished by their large capstone balanced on upright stones, often creating a portal-like appearance.

Wedge Tomb – Typically found in the west of Ireland, these tombs are narrower at one end and wider at the other, resembling a wedge shape from above.

Cist – Small stone-built coffin-like boxes used to hold the bodies or the cremated remains of the dead.

Specific to Wales

Cromlech – A Welsh term traditionally used to describe prehistoric megalithic structures, especially portal tombs or dolmens.

Quoit – Another term used in some parts of the British Isles, including Wales, to describe dolmens.

Round Barrow – A type of barrow that is circular in shape and standard across the British Isles, including Wales.

Bryn Celli Ddu is a specific example of a passage tomb known for its unique features in Anglesey, Wales.

These terms reflect the diversity of burial practices and architectural styles in prehistoric Europe, especially across Ireland and Wales, where regional variations are prominent due to different cultural influences and historical development. Each name identifies a type of structure and often conveys information about its form, function, and cultural significance.

We can declutter these 14 categories into just four associated sites, stopping this absolute confusion between archaeologists and making more sense of what we see.

1. Dolmens

Dolmen / Cromlech / Quoit: These terms are generally used interchangeably to describe a megalithic structure with large upright stones supporting a horizontal capstone. While “dolmen” is the more universally used term, “portal tomb” is common in Ireland, “cromlech” in Wales, and “quoit” in some parts of the British Isles.

2. Barrows and Cairns

Barrow / Tumulus / Round Barrow / Long Barrow / Court Tomb: These terms describe mounds of earth and stone raised over graves. “Barrow” and “tumulus” are broadly used, while “round barrow” and “long barrow” specify the shape and possibly the cultural context of the mound.

Cairn: While often used to describe piles of stones used as markers, in a burial context, cairns serve as stone-built mounds over graves, akin to earthen barrows but constructed with stones.

Court Tomb: Found primarily in Northern Ireland, these tombs include an open entrance area or “court,” which leads into a more enclosed burial chamber, reflecting a variation within the megalithic tomb group.

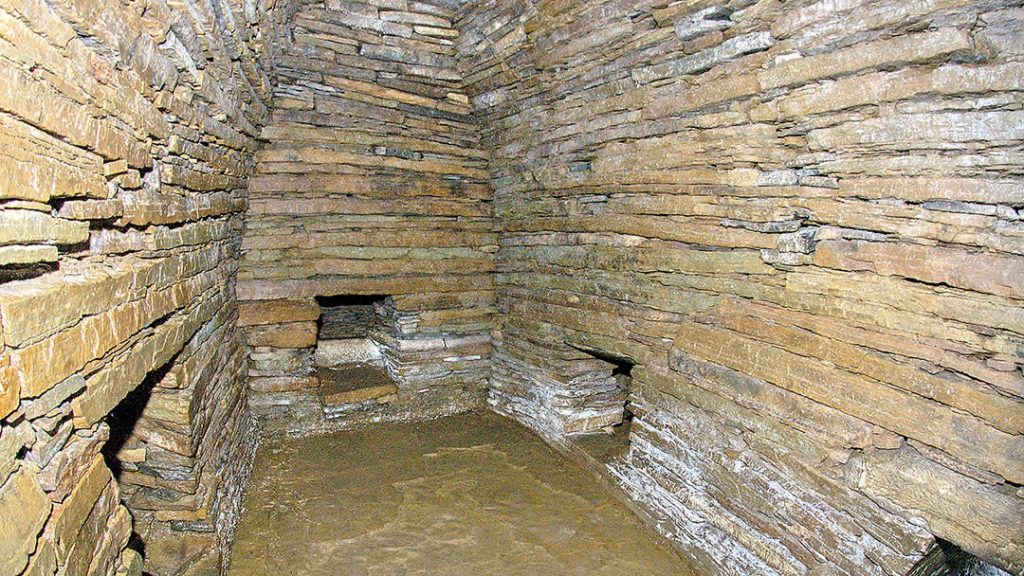

3. Chambered Tombs

Chamber Tomb / Passage Tomb / Wedge Tomb / Portal Tomb: This category includes structures that have an enclosed space with one or more chambers. “Passage tomb” refers to tombs with a long entrance passage leading to a central chamber, commonly seen in sites like Newgrange in Ireland. “Wedge tomb,” a term used in Ireland, describes a chamber tomb shaped like a wedge.

Bryn Celli Ddu: A specific type of passage tomb found in Wales, noted for its unique architectural features.

4. Burial Enclosures

Cist: These are small stone-built boxes across the British Isles, including Ireland and Wales. Cists typically hold the remains of a single individual either through inhumation or cremation. They can be found within more prominent barrows or cairns or as standalone burial sites.

These categories help simplify and clarify the relationships between the different terms used to describe prehistoric burial sites, reflecting their structural characteristics and geographical variations.

Dolmen and Barrow sites – Stonehenge

The connection between palisade and excarnation practices and their relevance to structures like dolmens and long barrows during the early phases of Stonehenge’s history offers a fascinating glimpse into Neolithic beliefs and funerary customs.

Excarnation

Excarnation refers to the practice of exposing a body to the elements and, particularly, to birds of prey as a means of disposing of the flesh before the bones are finally interred. This practice is based on the belief that it helps the soul of the deceased ascend to the afterlife, a realm often conceptualised as the “sky” or an aerial domain shared with ancestral spirits.

Palisade

The palisade found at Stonehenge likely served a practical and symbolic role. Practically, it protected the exposed bodies during excarnation from terrestrial scavengers, allowing only birds access to the remains. Symbolically, it delineated a sacred space, isolating it from the everyday world and marking it as a liminal area where the living could interact with the dead and the divine.

Stonehenge environment

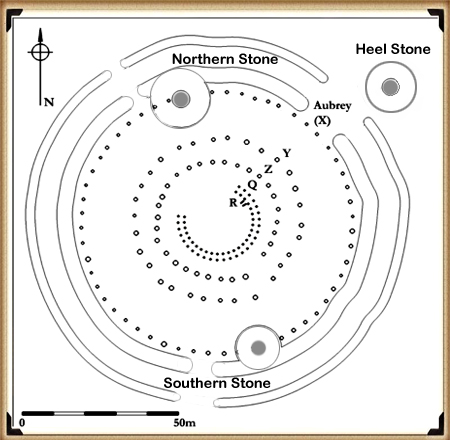

In my book ‘The Stonehenge Enigma,’ I highlight the process and the empirical evidence supporting the idea that the original site (Phase 1) was a reincarnation site. This is indicated by a semi-circle of reincarnation stones, with the Q & R supporting stones facing the northwest moon alignment, and a palisade surrounding these stone holes. Furthermore, a second palisade isolated the Stonehenge site, effectively cutting it off as a peninsula for similar reasons.

Dolmens

These simpler forms of megalithic tombs might not have been directly involved in excarnation but could represent a subsequent phase in the funerary process where the cleaned bones were finally laid to rest. Although more commonly associated with earlier Neolithic practices, the conceptual connection to death and the afterlife is clear.

Long Barrows

These are more directly connected to the types of funerary practices involving excarnation. Long barrows could house multiple individuals and often had long, narrow chambers that could store bones post-excarnation. However, not much remains. The Normanton Long Barrow near Stonehenge exemplifies how these barrows could serve as final resting places for bones prepared through excarnation. This particular barrow’s boat shape and surrounding moat emphasise the Mesolithic symbolism of journey and transition, aligning with beliefs about water as a medium to the afterlife.

The overall landscape around Stonehenge, with its combination of sacred spaces marked by palisades, areas for excarnation, and burial sites like long barrows and possibly dolmens, reflects a complex belief system where the realms of the living, the dead, and the divine were intricately connected. This cultural landscape allowed for the integration of practical and symbolic elements to facilitate the community’s mundane and spiritual needs. Such practices illustrate a deep and complex understanding of life, death, and the afterlife, showing how our ancestors used their environment and architectural ingenuity to reflect and enhance their spiritual and social worlds.

Excarnation and Storage areas for the bones

It’s important to realise that the earliest land burials occurred within Long Barrows, the world’s oldest known storage tombs throughout Northern Europe. This makes dating burial practices somewhat easier, as the later cremations belong to a different culture and shouldn’t be mixed up with the megalithic culture, a mistake that’s become common among today’s archaeologists.

This misconception extends to Stonehenge, our oldest monument, which is now dated by the remains of cremated bones that were actually left and buried much later. This flawed approach has inaccurately pushed forward the construction date of Stonehenge by 5,000 years, distorting and undermining the site’s true history.

In other parts of the country, like Wales and Ireland, Dolmens are common but Long Barrows are not as frequent. It’s possible that bones were moved to other storage areas besides Long Barrows, with round Chambered tombs being sensible alternatives in some regions. This variation could indicate a later change in burial practices or that the destruction of these monuments over the years has left archaeologists struggling to understand their original use. Consequently, they may reconstruct these sites incorrectly, based on their misunderstandings of our history.

Bad Science

Misidentification and bad practices also plague the analysis of megalithic structures, such as Dolmens, which are often assumed to have been tombs originally covered by mounds or soil that have since eroded away. This ‘leap of faith’ is based on a flawed analysis that suggests Dolmens were designed to keep vermin away from bodies and that covering them with a mound would lead to cave-ins due to soil entering through large gaps. If this assumption were accurate, we would expect to find sites with varying levels of soil erosion. Still, instead, we see sites consistently devoid of soil, which defies logic and represents bad science.

Moreover, when excavations are conducted at such sites, like ‘Arthur’s Tomb’, and a normal palisade is found confirming the site as an excarnation site, these are mistakenly identified as earlier roundhouses. This shows a fundamental lack of historical understanding, even at the PhD level in archaeology.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

(Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History)

Pages

- 1003037 – Ditch 530yds (484m) SW of Stitchcombe Farm

- 1003254 – Linear earthwork NW of Sidbury camp

- 1003726 – Earthwork 360yds (328m) NW of Warren Copse

- 1003769 – Grim’s Bank: section extending 560yds (510m) in Pennsylvania Wood, Ufton Park

- 1003784 – Wansdyke: section 610yds (560m) NW of Wernham Farm to 250yds (230m) SW of New Buildings

- 1003804 – Dray’s Ditches See also LUTON 1

- 1004534 – Dray’s Ditches See also BEDFORDSHIRE 1

- 1004719 – Wansdyke: section from S of Furze Hill to Marlborough-Pewsey road

- 1004736 – Section of the Wansdyke

- 1005373 – Grim’s Bank: section extending 300yds (275m) in Church Plantation

- 1005374 – Grim’s Bank: section extending 880yds (795m) in Old Warren

- 1005375 – Grim’s Bank: section extending 470yds (430m) in Little Heath

- 1005376 – Grim’s Bank: Section extending SW 900yds (825m) from New Plantation, Ufton Park, to a point 250yds (230m) SE of Rectory

- 1005377 – Grim’s Bank: section extending 420yds (400m) in Old Park and Raven Hill, Ufton Park

- 1005386 – Wansdyke (now Bedwyn Dyke), section 530yds (490m) on W side of Old Dyke Lane

- 1005389 – Grim’s Bank: section extending 240yds (220m) E of Padworth Gully

- 1006958 – Boundary ditch E of Near Down

- 1006977 – Ditch on Boydon Hole Farm

- 1006981 – Grim’s Ditch: section 1 mile long E from Southfield Shaw to Streatley parish boundary

- 1006982 – Grim’s Ditch: two sections in Portobello Wood, Holies Shaw and High Holies Wood Gap

- 1007136 – Bishop’s Dyke (Cumbria)

- 1007525 – Three (Cross) Dykes on Middle Hill – Kidland Forest Northumberland

- 1008274 – Cross dyke, 200m south east of Hosedon Linn

- 1008275 – Cross Dyke South East of Uplaw Knowe

- 1010988 – Hadrian’s Wall and Vallum from A6071 to The Cottage in the case of the Wall, and to the road to Oldwall, for the Vallum, in wall miles 57, 58 and 59

- 1010990 – The Vallum between the road to Laversdale at Oldwall and Baron’s Dike in wall miles 59 and 60

- 1010992 – Hadrian’s Wall and Vallum between the field boundary west of Carvoran Roman fort and the west side of the B6318 road in wall mile 46

- 1011396 – Cross dyke, South of Campville

- 1014695 – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum between Mill Beck and the field boundary east of Kirkandrews Farm in wall mile 69

- 1014708 – section of the north Oxfordshire Grim’s Ditch at Model Farm on the Ditchley Park Estate

- 1016860 – Scot’s Dike

- 1017288 – Wansdyke and associated monuments from east of The Firs to the eastern side of Tan Hill

- 1017736 – Cross Dyke and two building foundations at Copper Snout

- 1020643 – North east of Buttington Farm

- Britain’s Linear Earthworks (Dykes) Gazetteer

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Facebook Group Link Page

- Free Stonehenge LiDAR 3D Map

- Free Stonehenge LiDAR 8k Map

- Free Stonehenge LiDAR Water Map

- LiDAR Mapping Service – Contact Page

- Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Prehistoric Bedfordshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Berkshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Buckinghamshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Cambridgeshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Cheshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Cornwall Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric County Durham Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Cumbria Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Derbyshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Devon Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Dorset Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Durham Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Essex Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Gloucestershire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Hampshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Herefordshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Kent Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Lancashire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Leicestershire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Lincolnshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Middlesex Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Norfolk Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Northamptonshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Northumberland Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Oxfordshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Shropshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Somerset Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Suffolk Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Surrey Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Sussex Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Warwickshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Wiltshire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Worcestershire Canals (Dykes)

- Prehistoric Yorkshire Canals (Dykes)

- Stonehenge: The World’s First Computer

- The Stonehenge Enigma