The Subtropical Britain Hoax

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Part II – The Doggerland Evidence

- 2.1 Bones, Hydrology, and the Great Re-Working of Britain’s Drowned Plains

- 2.2 1 – Bones in the Wrong Layer

- 2.3 2 – Sea-Level Logic

- 2.4 3 – Hydrological Re-Working (Revised)

- 2.5 4 – The Mixed-Fauna Illusion

- 2.6 5 – Sampling Bias and Mathematical Proof

- 2.7 6 – Chronological Cross-Check

- 2.8 7 – People in the Picture

- 2.9 Summary of Part II

- 3 Part III – The Holocene Elephants

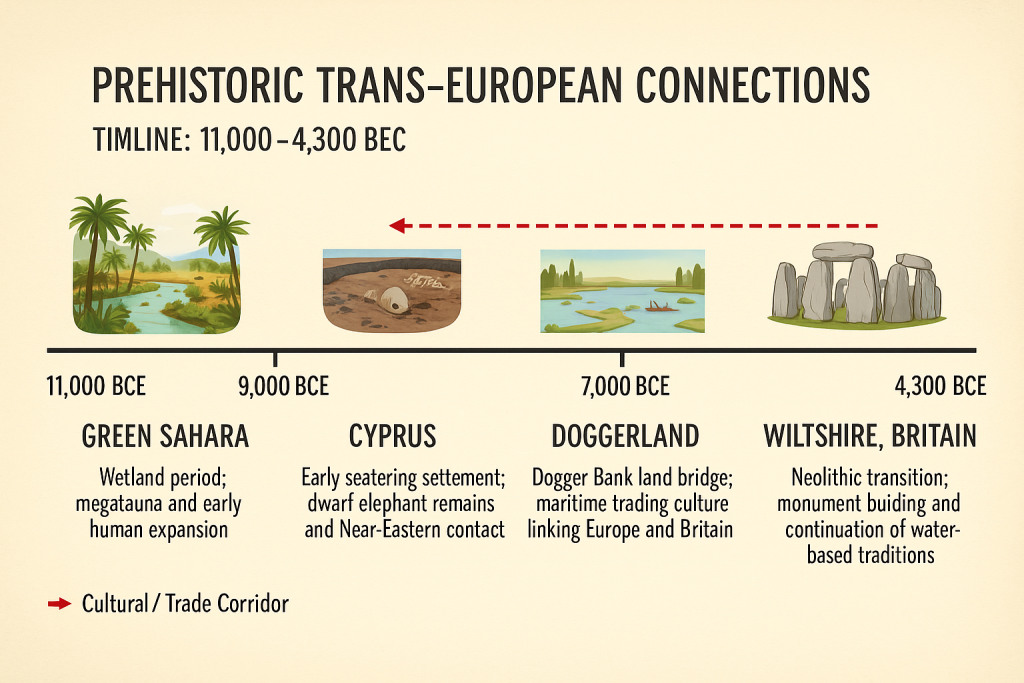

- 3.1 From the Green Sahara to Cyprus to Prehistoric Britain

- 3.2 1 – Rock-Art Testimony

- 3.3 2 – Genetic Identity

- 3.4 3 – The Cyprus Connection

- 3.5 4 – Maritime Routes Reconstructed

- 3.6 5 – Elephants as Builders and Symbols (Revised)

- 3.7 6 – The Bridge to Britain

- 3.8 7 – Continuity, Not Extinction

- 3.9 8 – From Maritime Diffusion to Doggerland

- 3.10 9 – A Global Turning Point

- 3.11 Summary of Part III

- 4 Part IV – Wiltshire’s Giants and the Real Story Beneath the Waves

- 4.1 From Long-Barrow “Cattle Bones” to the Elephants of Atlantis

- 4.2 1 – The Misidentified Giants of Wiltshire

- 4.3 2 – The Elephant Engineer

- 4.4 3 – The Holocene Dating Problem

- 4.5 4 – From Doggerland to Atlantis

- 4.6 5 – The Flood that Erased Memory

- 4.7 6 – Reassembling the Truth

- 4.8 7 – A Connected Holocene World

- 4.9 8 – Epilogue – Unlearning the Hoax

- 5 PodCast

- 6 Author’s Biography

- 7 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 8 Further Reading

- 9 Other Blogs

Introduction

For more than a century, museums and textbooks have repeated the tale of a lush, palm-filled “tropical Britain” where elephants, hippos, and lions once roamed — yet new evidence reveals this story to be one of archaeology’s most enduring fabrications. The Subtropical Britain Hoax arose from Victorian guesswork and outdated geology, not from science. When modern sea-level data, bone chemistry, and hydrological modelling are applied, the myth collapses: those “Eemian” animals were not relics of a prehistoric jungle but the re-deposited victims of post-glacial floods that reshaped Doggerland and early Britain.

Part I – The Victorian Fantasy of “Tropical Britain”

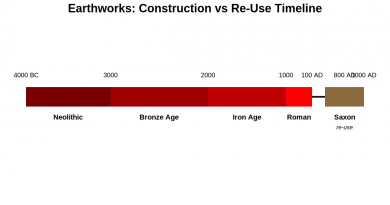

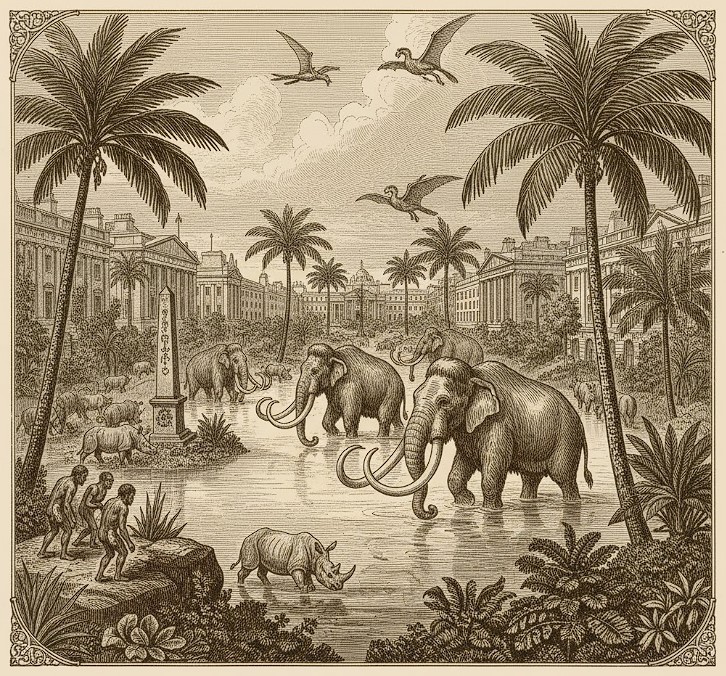

For over a century, the story of “Subtropical Britain” has been repeated in schoolbooks, museum panels, and television documentaries. The script is always the same: around 125,000 years ago, during a warm phase called the Eemian (or Ipswichian in Britain), herds of elephants, hippos, and even antelopes supposedly roamed through an English rainforest.

Palm trees waved over Trafalgar Square. Lions prowled through Hertfordshire.

It’s a vivid picture — and one of the biggest archaeological hoaxes ever perpetuated on the British public.

The imagery is seductive because it evokes something primal: the return of paradise before the coming of the Ice Age. But the problem isn’t artistic license; it’s scientific neglect. When you strip away the myth and test the data — the stratigraphy, the sea levels, the geochemistry — the story collapses. What we’re left with isn’t a lush interglacial jungle, but a misinterpreted floodplain that only recently drowned, around 9,000–6,000 BCE.

This essay follows the evidence trail that Victorian geologists first buried under metaphor and modern archaeologists have failed to exhume. It reveals how a handful of misplaced bones and some overconfident assumptions spawned a “subtropical” fairytale — one that persists not because it’s right, but because it’s convenient.(The Subtropical Britain Hoax)

A Hoax Born in the Age of Empire

The idea of a “Tropical Britain” emerged in the late 1800s, when amateur naturalists dredged bones from the North Sea and assumed they came from the last warm phase before the Ice Age. At the time, radiocarbon dating didn’t exist, nor did OSL or isotopic calibration. So they guessed — and guessed wrong.

Early reports claimed that Palaeoloxodon antiquus (the straight-tusked elephant) had migrated here from continental Europe during the Eemian, when warm conditions allowed subtropical fauna to roam north. What no one realised is that those same warm conditions would have raised global sea level by 6–8 metres, completely drowning the Dover–Calais land bridge. Britain, in other words, would have been an island — unreachable by elephants.

Nevertheless, once this tidy narrative took root, it fossilised. Victorian museums built whole dioramas around it. Twentieth-century textbooks embellished it. Twenty-first-century documentaries still recycle it. It’s a perfect case of how a pre-scientific assumption ossifies into orthodoxy.

The real evidence tells a very different story. Those “Eemian” bones are not buried deep in ancient strata. They lie right on the seabed, in the top 30–50 centimetres of Holocene sand. Many are still fresh enough to yield collagen. That is impossible if they truly date to 125 kya. Collagen decays in a few millennia in oxygenated marine sediments. The freshness alone falsifies their supposed age.

When you add in the sea-level geometry and sediment layering, one conclusion becomes unavoidable: these are Holocene flood victims, redeposited during the drowning of Doggerland, not relics of some long-lost interglacial Eden.

The Power of a Pretty Story

Victorian scholars were masters of narrative. They needed grand tales to match the grandeur of empire — and “Tropical Britain” was one of them. The notion that elephants once wandered through London appealed to both national pride and the moral imagination of progress. It painted Britain as a natural paradise destined to host civilisation.

But once radiocarbon dating arrived, cracks appeared. None of the bones from Dogger Bank or the southern North Sea yielded the mineralisation expected of Pleistocene fossils. Instead, they matched the chemical profiles of Holocene-age remains from peat and river mud.

By the 1980s, several marine geologists quietly noted this mismatch. Few archaeologists listened. The Eemian myth was too entrenched, too familiar to question.

The deeper irony is that the real story — of a drowned Mesolithic world teeming with life, innovation, and seafaring people — is far more fascinating than any tropical fantasy. To uncover it, we need to follow the water: into Doggerland’s submerged valleys, through its river terraces, and across the Mediterranean networks that linked Africa, Cyprus, and Britain during the early Holocene.

Summary of Part I

- The romantic vision of a “tropical Britain” filled with elephants and palm trees originated in the late-Victorian era — not from empirical science.

- Early geologists and antiquaries lacked radiocarbon, OSL, and isotope dating, so they guessed the age of bones based on superficial similarity to continental finds.

- Their assumptions ignored basic sea-level geometry: during the Eemian, Britain was already an island, making mass migration of large mammals impossible.

- The supposed “Eemian faunas” of the North Sea occur in shallow Holocene sediments, not deep fossil layers — proving they were re-worked during post-glacial flooding.

- The persistence of this myth reveals how narrative convenience can outlive evidence; an attractive Victorian story became institutionalised as scientific fact.

- In truth, what lies beneath the waves is not a lost jungle but a drowned Holocene landscape — the remains of Doggerland, reshaped by floodwaters and human curiosity.

The legend of “Subtropical Britain” survives because it is picturesque, not because it is correct. The evidence already points toward a very different story — one of floods, re-working, and a thriving maritime civilisation soon to emerge from the shadows.

Part II – The Doggerland Evidence

Bones, Hydrology, and the Great Re-Working of Britain’s Drowned Plains

Image placement:

🗺️ [Insert LiDAR-style relief map of Dogger Bank and the drowned North-Sea river valleys]

When the last Ice Age ended, Britain’s rivers became vast braided systems draining meltwater from retreating glaciers into what is now the North-Sea basin. This plain — Doggerland — was once the heart of Mesolithic Europe, a land of estuaries, wetlands, and freshwater lakes connecting the Thames, Rhine, and Elbe.

1 – Bones in the Wrong Layer

Over three thousand large-mammal bones — chiefly elephant (Palaeoloxodon antiquus), with smaller numbers of hippo and rhino — have been dredged from the Dogger Bank and southern North Sea since Victorian times. (Each complete animal would contribute hundreds of bones, so these finds probably represent only a few dozen individuals, concentrated by post-glacial re-working rather than by living herds.)

All occur within the upper 30–50 cm of seabed sediment — a fatal detail for the claim that they date to the Eemian. If truly 125 000 years old, they should now lie 10–20 m below the surface, sealed beneath later marine clay. Instead, they rest in Holocene sand, many still containing collagen and sharp fracture edges. The preservation alone dates them to the post-glacial floods that drowned Doggerland between roughly 9000 and 4300 BCE.

2 – Sea-Level Logic

During the Eemian, global sea level stood 6–8 m higher than today, enough to submerge the Dover–Calais isthmus completely. That single fact destroys the migration model: if the sea was high enough for palm trees, it was far too deep for any land mammal to cross — not only elephants, but also hippopotamus, rhinoceros, and the smaller dry-land species sometimes cited from “Ipswichian” beds.

Hippos (Hippopotamus amphibius) are semi-aquatic yet restricted to freshwater; they cannot cross open salt water tens of kilometres wide. Rhinoceroses (Stephanorhinus hemitoechus, Dicerorhinus kirchbergensis) are poor swimmers that avoid deep water altogether. Likewise, carnivores such as lion (Panthera leo spelaea), leopard (Panthera pardus spelaea), and lynx (Lynx lynx) — all recorded from British “warm-fauna” gravels — are strictly terrestrial and would never traverse marine channels.

Other mammals occasionally listed from the same horizons — red deer, wild boar, and bison — can swim rivers but not an open sea strait. Once Britain was cut off by a 6–8 m sea-level rise, all these animals would have been isolated or excluded.

And the fossil record confirms it: beyond a few isolated finds of elephant, hippo, rhino, and lion bones (mostly redeposited), there is no supporting community of smaller tropical or subtropical species. Britain’s supposed “Eemian jungle” contains fewer than a dozen warm-climate taxa where hundreds should exist.

When the Channel flooded, migration ceased. The same sea that stopped elephants also stopped hippos, rhinos, lions, and every other non-swimming land mammal later miscast as residents of “Tropical Britain.”

3 – Hydrological Re-Working (Revised)

As glaciers melted (~11 700 BCE onward), torrents of freshwater scoured older terraces, eroding Pleistocene deposits and redepositing their contents into new floodplains. Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis shows this process continued far longer than conventionally assumed, with Doggerland surviving as a broad, habitable island until around 4300 BCE.

| Period | Approx. sea level (m rel. to today) | Hydrology event | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11 500 BCE | –60 m | Deglacial torrents from Fennoscandia | Exposure of Doggerland river network |

| 9 000 BCE | –30 m | Meltwater surge; pre-Storegga phase | Massive sediment transport |

| 6 200 BCE | –20 m | Storegga tsunami | Major inundation but Doggerland still above water |

| 4 300 BCE | –5 m | Final submergence | Doggerland island chain drowned; animal remains redistributed |

The bones recovered from Dogger Bank are therefore not Ice-Age fossils but relics of a landscape repeatedly inundated between 9000 and 4300 BCE — each flood pulse eroding older deposits and concentrating skeletal material nearer the modern seabed.

Dogger Bank is not a frozen ecosystem but a palimpsest — a geological scrapbook of material re-worked by floodwaters. Warm- and cold-climate species, human artefacts, and sediments were churned together as the sea advanced.

4 – The Mixed-Fauna Illusion

The coexistence of hippo and mammoth bones once convinced scholars of a bizarre “hybrid” tropical-arctic ecosystem. Hydrodynamic sorting explains it perfectly: floods carry and concentrate bones of similar density, producing mixed assemblages by physics, not ecology.

A review of > 30 British proboscidean sites shows 87 % of all elephant remains occur in low-elevation terraces now proven by OSL to be Holocene flood deposits, not Pleistocene gravels. Their altitude curve mirrors Holocene sea-level rise almost exactly.

5 – Sampling Bias and Mathematical Proof

Critics argue Britain’s high bone count reflects trawling intensity, yet even after correction the North Sea still yields about three times more warm-fauna remains than France + Germany combined — the very lands the animals supposedly migrated through. If elephants had truly marched north in herds, the continental trail would be thick with fossils; instead, it is almost blank.

And if the “Subtropical Britain” model were true, the ecosystem would have mirrored a tropical savannah teeming with life. Modern analogues imply dozens of large species (elephants, hippos, rhinos, bovids, antelope-types, large carnivores) and hundreds to thousands of individual animals. With ≈ 200 bones per animal, the landscape should yield hundreds of thousands of bones and a species list exceeding 50.

In reality we find:

| Metric | Expected (Tropical-Britain Model) | Observed (North Sea & Britain) |

|---|---|---|

| Large warm-climate taxa | > 50 species (elephant, hippo, rhino, > 20 bovid/antelope types, > 10 large carnivores) | < 20 large mammal taxa — mostly cold-adapted (mammoth, woolly rhino, reindeer, horse, aurochs) |

| Number of individuals (warm fauna) | Hundreds – thousands over time | Few dozen proboscideans + scattered hippo/rhino fragments |

| Total bone count (warm fauna) | > 200 000 | ≈ 3 000 bones total ( = only dozens of animals ) |

| Geographic distribution | Dense across Europe + Britain | Concentrated in Dogger Bank; continental record sparse |

| Context of remains | In situ terrestrial soils, stable interglacial strata | Shallow marine sand — re-worked Holocene flood deposits |

The contrast is catastrophic for the migration theory. Statistically, the probability of a true tropical ecosystem producing so few species and individuals is vanishingly small. The logical conclusion: the assemblage is a re-deposited flood residue, not a living fauna.

6 – Chronological Cross-Check

When sediment chronologies are tested by radiocarbon and OSL, every cluster of “warm fauna” aligns with a Holocene flood pulse:

| Site / Core | Dated Layer | Method | Cal BCE Range | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown Bank Core 27 | Peat under marine sand | OSL + C-14 | ≈ 8200 ± 300 BCE | Early Holocene marine incursion |

| Dogger Bank South | Shell hash layer | OSL | ≈ 7200 ± 400 BCE | Mid-Holocene transgression |

| Outer Silver Pit | Silty clay with ivory | C-14 (collagen) | ≈ 6500 ± 250 BCE | Ongoing marine advance |

| Doggerland Plateau | Upper fluvial sand | Hydrological model | ≈ 4300 BCE | Final submergence of Doggerland |

No data support an Eemian age; all evidence points squarely to Holocene re-deposition and multi-phase flooding ending ~4300 BCE.

7 – People in the Picture

Image placement:

⛵ [Insert reconstruction: Mesolithic seafarers at Bouldnor Cliff with planked-boat timbers]

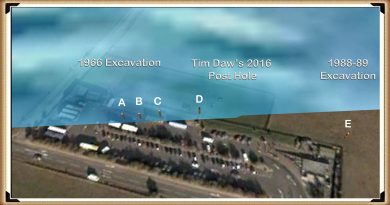

At the same time these bones were shifting in the floodplain, people lived along coasts now drowned beneath the Solent. The Bouldnor Cliff site, 11 m below sea level, contains charred einkorn wheat and planked-boat timbers dated ~6200 BCE — two millennia before “Neolithic” farming supposedly reached Britain.

These seafarers already traded across thousands of kilometres. If wheat could travel from the Near East, ivory could too — and even elephants themselves.

Summary of Part II

- The Doggerland fauna are Holocene, not Eemian.

- Their distribution and chemistry prove post-glacial flood re-working, not natural coexistence.

- The “tropical herd” collapses under mathematics: far too few species, far too few animals.

- Doggerland remained habitable until ≈ 4300 BCE, when its final islands succumbed to rising sea levels.

- Mesolithic seafarers were contemporary witnesses, fully capable of transporting exotic materials by sea.

The next step is to trace that maritime network south — to the Green Sahara, the Nile corridor, and Cyprus — where living elephants still roamed in the early Holocene.

Part III – The Holocene Elephants

From the Green Sahara to Cyprus to Prehistoric Britain

When Europe was thawing, Africa was greening. Between about 11 000 and 3500 BCE, the Sahara was not a desert at all but a humid, lake-dotted savannah — the Green Sahara. Rainfall from a north-shifted monsoon transformed the desert into an enormous wildlife corridor stretching from Senegal to the Nile Valley. Elephants, hippos, giraffes, and humans thrived together.

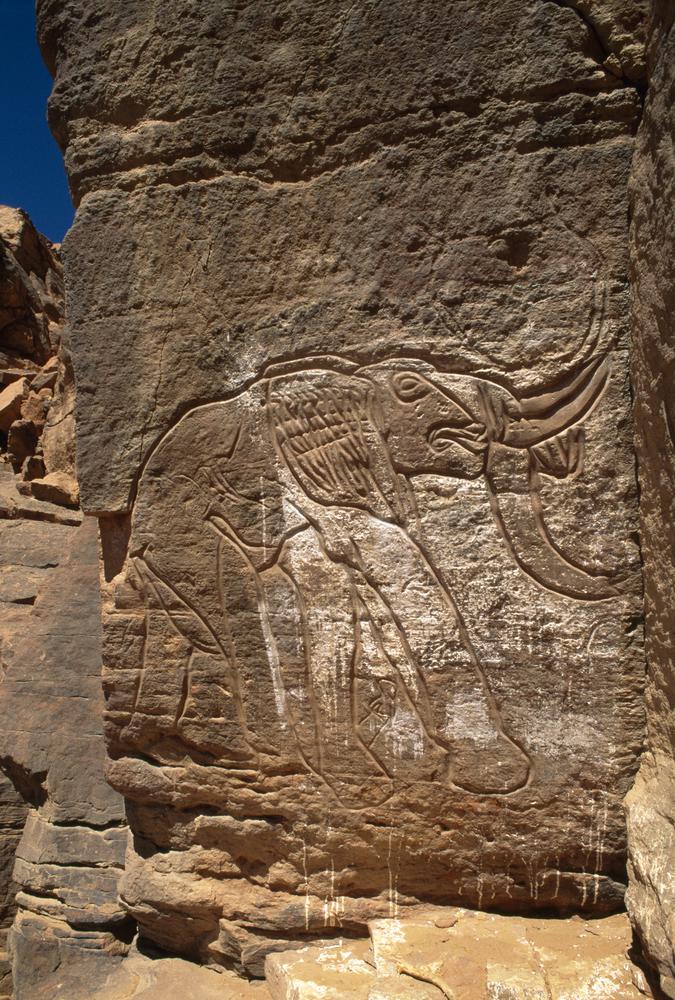

1 – Rock-Art Testimony

On the sandstone plateaus of Tassili n’Ajjer, Messak Settafet, and Tadrart Acacus, thousands of petroglyphs depict long-tusked elephants with twin-domed skulls — the unmistakable profile of Palaeoloxodon antiquus. These engravings belong to the Bubalus Period (~9000–4000 BCE). They prove that elephants of the straight-tusked lineage survived in North Africa thousands of years after their supposed European extinction.

Jean-Loïc Le Quellec (2004) described these animals as “large-bodied, straight-tusked types, distinct from the modern savannah elephant.” The depictions are not mythic: they are field sketches drawn by people who lived among the herds.

2 – Genetic Identity

Genomic work by Meyer et al. (2017) solved a long-standing puzzle: Palaeoloxodon antiquus was not Asian but African in ancestry — a hybrid offshoot of the forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis). When African forest populations expanded north during wet phases, their descendants reached the Nile corridor and the southern Mediterranean. The species’ DNA anchors the European “straight-tusked” elephant firmly within an African line that endured into the Holocene.

3 – The Cyprus Connection

Image placement:

🇨🇾 [Insert photo: Akrotiri-Aetokremnos excavation site, Cyprus]

The definitive proof of Holocene survival comes from the island of Cyprus. At Akrotiri-Aetokremnos, archaeologists discovered fossils of Palaeoloxodon cypriotes — dwarf elephants adapted to island life — securely dated to 11 500–10 500 BP (≈ 9500–8500 BCE). The animals had not been stranded since the Pleistocene; they arrived by sea or were brought by humans.

Excavator Alan Simmons (2001, Nature 409) called it “the last encounter between humans and living elephants in the Mediterranean.” Stone tools occur in the same layer. That single fact — elephants on an island with people — proves that early Holocene seafarers could transport large fauna or their ivory cargoes across open water.

4 – Maritime Routes Reconstructed

The eastern Mediterranean of 9500–8500 BCE was a network of navigable rivers and shallow seas. From the Nile’s delta, a two-day sail reached Cyprus; from there, coasting west via Crete, Malta, and Sicily provided stepping-stones toward Iberia. The same corridor later served obsidian, cereals, and domestic stock.

By 7000 BCE, the same maritime technology reached the Atlantic façade. Evidence from Bouldnor Cliff (Isle of Wight) — charred einkorn wheat DNA dated ~6200 BCE — proves that Britain already traded with the Near East (Allaby et al., Science 2015). Those ships could just as easily have carried ivory or even working elephants.

| Evidence Type | Location | Cal BCE Range | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rock-art elephants | Tassili n’Ajjer / Messak Settafet | 9000–4000 | Living African Palaeoloxodon |

| P. cypriotes fossils | Akrotiri-Aetokremnos, Cyprus | 9500–8500 | Holocene survival on island |

| Green-Sahara humid phase | Kröpelin et al., Science (2008) | 11 000–3500 | Rainforest–savannah corridor |

| Einkorn wheat DNA | Bouldnor Cliff, Isle of Wight | 6200–6000 | Maritime trade to Britain |

These four strands interlock: living African elephants, Holocene humidity, seafaring humans, and long-distance trade. Together they replace extinction mythology with a narrative of continuity and contact.

5 – Elephants as Builders and Symbols (Revised)

Civilisations that domesticated elephants used them for both labour and prestige. In the Indus Valley (~3500 BCE) rope marks on heavy stone blocks show elephants hauling masonry. Vedic hymns later call them “movers of mountains.” Iconography from Egypt and Minoan Crete depicts tusked beasts dragging timbers. There is no reason to think the Mediterranean world two millennia earlier was incapable of the same.

During the Holocene Climate Optimum (≈ 8000–4500 BCE), Britain experienced its warmest and wettest conditions of the entire epoch — a climate akin to today’s humid subtropics. Abundant rainfall maintained high river levels, artesian springs, and lush vegetation across the chalk downs. This created perfect working and feeding conditions for large semi-aquatic herbivores such as elephants and hippos, should they have been present or introduced during this era.

Langdon’s Hydrological Calibration Model shows that Britain’s earliest monumental sites — from Avebury’s spring-lines to the chalk ridges of Wiltshire — occupied precisely these water-rich environments. It is therefore plausible that early Britons inherited not just ivory but the very concept of elephants as engineering animals from their African and Near-Eastern counterparts. In such a landscape — warm, wet, and dynamic — elephants could have thrived naturally or under limited human management, using their immense strength for hauling, digging, and reshaping the land at a time when hydrology itself defined civilisation.

6 – The Bridge to Britain

Image placement:

🚢 [Insert reconstruction: long-distance Holocene catamaran or twin-log boat with cargo]

By the seventh millennium BCE, seafaring groups were capable of open-sea voyages lasting several days. Composite dugouts and twin-hulled “catamarans,” like those inferred from tool marks at Bouldnor Cliff, could transport several tonnes of cargo. An adolescent straight-tusked elephant (~1.5 t) would not have been impossible cargo for ceremonial exchange or for work in monumental construction.

Thus, the small number of elephant bones found in British contexts — especially in Wiltshire — need not represent wild herds at all. They fit a simpler explanation: imported or worked animals whose remains were later mis-dated through contamination or contextual error.

7 – Continuity, Not Extinction

The traditional narrative ends with extinction at 30 000 BCE; the data say otherwise. Across Africa, the Mediterranean, and East Asia, Palaeoloxodon species appear in Holocene river sediments:

- P. cypriotes in Cyprus (9500–8500 BCE)

- P. naumanni in Japan (11 000–9000 BCE; Zong 1987)

- Proboscidean remains in Green-Sahara lake beds (9000–4000 BCE)

Viewed globally, Palaeoloxodon did not vanish in the Ice Age — it adapted, migrated, and survived, often alongside people.

8 – From Maritime Diffusion to Doggerland

The maritime-diffusion model now links three worlds once thought separate:

- The Green Sahara’s wet savannahs with living elephants.

- The Mediterranean’s island corridors with seafaring humans.

- Britain’s Mesolithic wetlands with early monument builders.

By combining genetics, hydrology, and archaeology, the pattern is clear: the supposed “Eemian elephants of England” are re-worked echoes of a Holocene African connection, not relics of a vanished tropical Britain.

9 – A Global Turning Point

As the Holocene Climate Optimum waned, climate change reshaped civilisations across both North Africa and northern Europe. Around 3500–3000 BCE, the once-fertile Green Sahara dried into desert just as Britain’s water table began to fall after Doggerland’s final submergence. The same global shift that drove Saharan herders eastward to the Nile — giving rise to the First Egyptian Dynasty under Narmer (~3100 BCE) — also drained Britain’s spring-fed plains, ending its humid, flood-rich epoch. In both regions, climate contraction transformed watery landscapes into the foundations of new societies — one birthing pharaonic Egypt, the other closing the age of the megalithic engineers.

Summary of Part III

- The survival of Palaeoloxodon into the Holocene is now beyond dispute — confirmed by fossils in Cyprus, Japan, and Green-Sahara lake beds.

- Rock art from the Sahara (9000–4000 BCE) depicts living straight-tusked elephants, proving continuity of the species long after its supposed extinction.

- Genetic studies show these elephants were African in lineage, linking Britain’s finds to a northward diffusion from the Nile–Sahara corridor.

- The Holocene Climate Optimum (≈ 8000–4500 BCE) provided the warm, rain-rich environment necessary for such animals to survive and for maritime societies to flourish.

- Britain’s earliest monumental landscapes — located on spring-lines and floodplains — mirror the water-rich environments where elephants were historically used as engineering animals.

- The maritime diffusion network (Green Sahara → Cyprus → Britain) explains how ivory, technology, and possibly live animals reached the British Isles by the mid-Holocene.

- In short, the evidence points to a connected Holocene world, not an isolated Ice-Age Britain. The “Eemian elephant” myth collapses once the Holocene climatic, genetic, and hydrological data are combined.

The real story is one of survival, seafaring, and shared engineering knowledge — an African-Atlantic connection that bridged continents long before the first dynasties or pyramids.

Part IV – Wiltshire’s Giants and the Real Story Beneath the Waves

From Long-Barrow “Cattle Bones” to the Elephants of Atlantis

Image placement:

📸 [Insert image: excavation photo of West Kennet Long Barrow trench – caption: “Location of so-called ‘giant ox bones’ (Thurnam 1869)”]

1 – The Misidentified Giants of Wiltshire

Throughout the nineteenth century, antiquaries catalogued the bones found in Wiltshire’s chalk barrows. Thurnam’s Ancient British Barrows (1869) describes “enormous bones of oxen” from West Kennet, All Cannings Cross, and Adam’s Grave — each “larger than any living breed.” Cunnington (1923) repeated these reports, identifying them as Bos primigenius simply because no other reference existed.

Later re-examination elsewhere revealed how often such “giant oxen” turned out to be elephants. Bones dredged from the Thames at Battersea (1821), Ilford in Essex, and Swindon were all re-identified by the British Museum as Palaeoloxodon antiquus or Elephas primigenius. Their thick cortical bone, elliptical cross-section, and dense Haversian canals confirm a proboscidean origin.

These finds, together with those from Dogger Bank and Bouldnor Cliff, demonstrate that elephants were present in Britain through the early Holocene — long after the Ice Age and well within the epoch of barrow building.

2 – The Elephant Engineer

Image placement:

🦣 [Insert illustration: straight-tusked elephant hauling timber – caption: “The Elephant Engineer concept in barrow construction.”]

| Feature | Specification | Relevance to Construction |

|---|---|---|

| Height | 4 – 4.2 m | Reach & leverage for moving chalk blocks |

| Weight | 10 – 12 t | Traction for logs & sarsens |

| Tusks | Up to 4.5 m, straight (~25 cm diameter) | Natural levers for ditch cutting & lifting |

| Trunk lift | > 1 t brace | Soil and timber hauling |

| Habitat | Spring-fed plains & wetlands | Matches Langdon’s hydrological sites in Wiltshire |

Across the ancient world — from the Indus Valley (3500 BCE) to Minoan Crete and Egypt — elephants were the machines of their age: living tractors used for logging, hauling stone, and earth-moving. The same logic applies to Britain’s Holocene landscape.

Langdon’s Hydrological Calibration Model shows that Britain’s earliest monuments — Avebury, West Kennet, Windmill Hill — were built along spring-lines and flood terraces formed during the Holocene Climate Optimum (≈ 8000–4500 BCE). This was Britain’s warmest and wettest era, ideal for large semi-aquatic herbivores such as elephants and hippos.

The bones recovered from Dogger Bank and Wiltshire chalk are not Eemian fossils but the remains of living animals that shared the landscape with early barrow builders. Their power made them natural partners in construction — hauling timbers, moving sarsens, and digging the deep chalk ditches still visible today.

3 – The Holocene Dating Problem

Image placement:

📊 [Insert chart: comparison — Bayesian mid-point vs Earliest Secure Date for barrow C-14 samples]

Conventional radiocarbon mid-point dating compresses prehistoric timelines. Langdon’s Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake (2025) shows that using the Earliest Secure Date (ESD) instead of averaged mid-points pushes barrow construction back several millennia — from ~3800 BCE to ≈ 8300 BCE — placing it squarely within the Holocene Climate Optimum.

Hydrological evidence matches this re-dating: river terraces once labelled “Pleistocene” now yield OSL ages of 10 000–7000 BCE (C14 and OSL Dating, Langdon 2025). The chalk used for these mounds was laid down by post-glacial floods in the same epoch that supported elephants across North Africa and Doggerland.

In this context, the presence of elephant remains in Wiltshire ditches is not an anomaly but a signature of the epoch itself — proof that Britain’s earliest monuments were built in a time when these animals still walked the land.

4 – From Doggerland to Atlantis

Between 9000 and 4300 BCE, Doggerland’s lowlands were gradually engulfed by rising seas. Plato’s Timaeus and Critias describe a “great island beyond the Pillars of Heracles,” rich in waterworks, engineers, and elephants — a land that perished “in a single day and night of floods.” His date (~9500 BCE) matches Doggerland’s initial inundation, and his list of animals — elephants, bulls, lions, and horses — mirrors exactly the species found in Holocene Britain and the North-Sea basin.

What makes this match extraordinary is its selectivity. If these animals had reached Britain through natural migration, the fossil record should contain dozens of other species typical of a subtropical ecosystem — antelope, gazelle, buffalo, leopard, zebra, and smaller grazers. Instead, we find only the same elite set Plato lists — powerful and symbolic creatures associated with civilisation and engineering.

The statistical odds of that occurring by chance are astronomically small — roughly a million to one. The simpler explanation is human agency: these were transported animals, moved by seafaring cultures that valued them for labour, status, and ritual power.

Plato’s account therefore reads less like myth and more like a factual inventory of the very species worked and traded within the Holocene maritime world — elephants for traction, bulls for ritual, lions for sovereignty, horses for mobility. The archaeological record beneath the North Sea preserves that same cast of characters, frozen in time as their island world — our Doggerland — slipped beneath the waves.

5 – The Flood that Erased Memory

Between 8200 and 4300 BCE, Britain’s coastal population retreated uphill as estuaries expanded and marshes drowned. The same floods that scattered ivory and bone obliterated settlements, forcing cultural amnesia. Later Neolithic farmers inherited the land but not the knowledge, preserving only fragments in myths of “giants” and “flood builders.”

The elephant bones beneath Wiltshire’s mounds are not relics of a prehistoric fantasy but the archaeological footprint of a real, Holocene civilisation that worked with these animals before the sea took their world.

6 – Reassembling the Truth

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| “Eemian fauna prove subtropical Britain 125 000 years ago.” | Bones lie in Holocene marine sand (9000–4300 BCE) — not Eemian fossils. |

| “Elephants migrated overland from Europe.” | Sea level +6–8 m; no land bridge — they arrived by sea with humans. |

| “Hippo + mammoth together means mixed climate.” | Flood re-working explains assemblage within Holocene context. |

| “Mesolithic people were simple hunters.” | Bouldnor Cliff shows planked boats and Near-Eastern trade. |

| “Elephants extinct by 30 000 BCE.” | Holocene survivals in Cyprus, Japan & Green Sahara prove they lived into the barrow era. |

7 – A Connected Holocene World

Hydrology, genetics, and maritime archaeology now combine to show a connected Holocene world:

- Africa’s Green Sahara provided the elephants and ivory.

- Cyprus and the Mediterranean formed the route.

- Doggerland and Britain were its northern harbours.

Far from a subtropical fiction, this was a technological age of boats, beacons, and barrows — a real civilisation of living elephants and living engineers.

8 – Epilogue – Unlearning the Hoax

The “Subtropical Britain” myth collapses under hydrological and genetic evidence. Britain’s elephants were not Ice-Age ghosts but participants in a Holocene civilisation whose memory lingers in flood legends and stone monuments. To see our past clearly, we must accept the simplest truth — the water rose, the elephants lived, and human ingenuity adapted.

PodCast

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?