Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

Contents

- 1 1. Introduction — Why This Debate Exists at All

- 2 2. Cro-Magnon ≠ Modern Human — Why Physiology Matters

- 3 3. The Fatal Modern Assumption: Abstract Measurement

- 4 4. The Aubrey Holes — Measurement Frozen in Geometry

- 5 5. The Megalithic Yard Reframed — Not a “Mystery Unit”

- 6 6. The Dating Mirage — Why C14 and DNA Mislead

- 7 7. Cranial Evidence — Long Heads and Long Barrows

- 8 8. Cambridge Confirmation — Megalithic Builders ≠ Beaker People

- 9 9. Trade, Not Invasion — The Beaker Distribution Problem

- 10 10. Brain Size and the “Efficiency” Excuse — When Biology Is Explained Away

- 11 11. The Neolithic Power Axe — Scale, Strength, and Feasibility

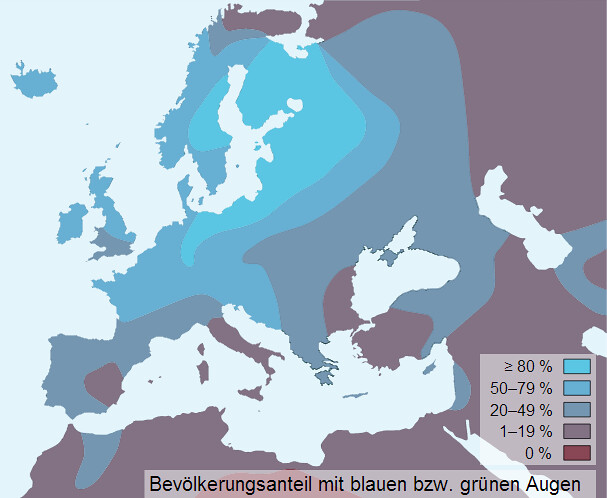

- 12 12. The Northern Genetic Continuum — R1b1 and Population Persistence

- 13 13. Pigmentation as an Inherited Ice-Age Signal

- 14 14. Eye Colour and Deep Ancestry in North-West Europe

- 15 Synthesis: Bodies, Continuity, and the Shape of the Past

- 16 Podcast

- 17 Author’s Biography

- 18 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 19 Further Reading

- 20 Other Blogs

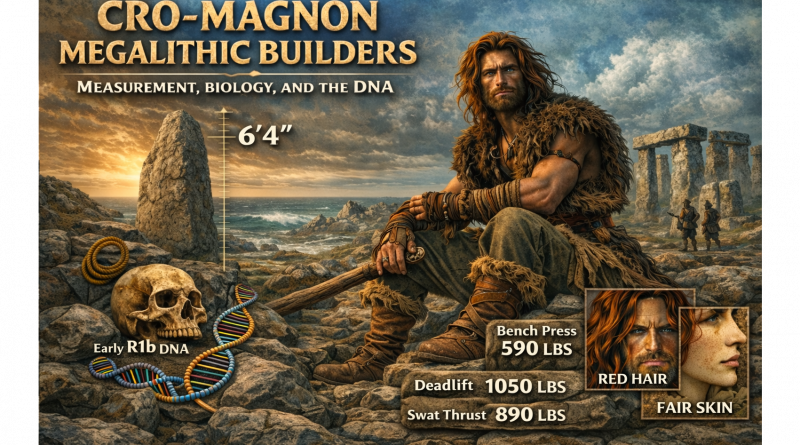

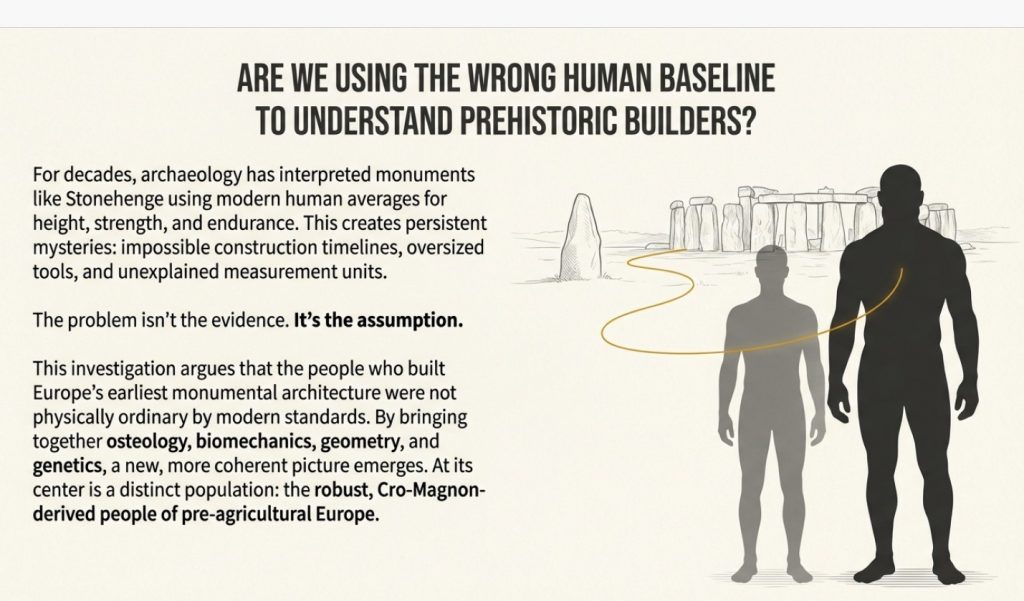

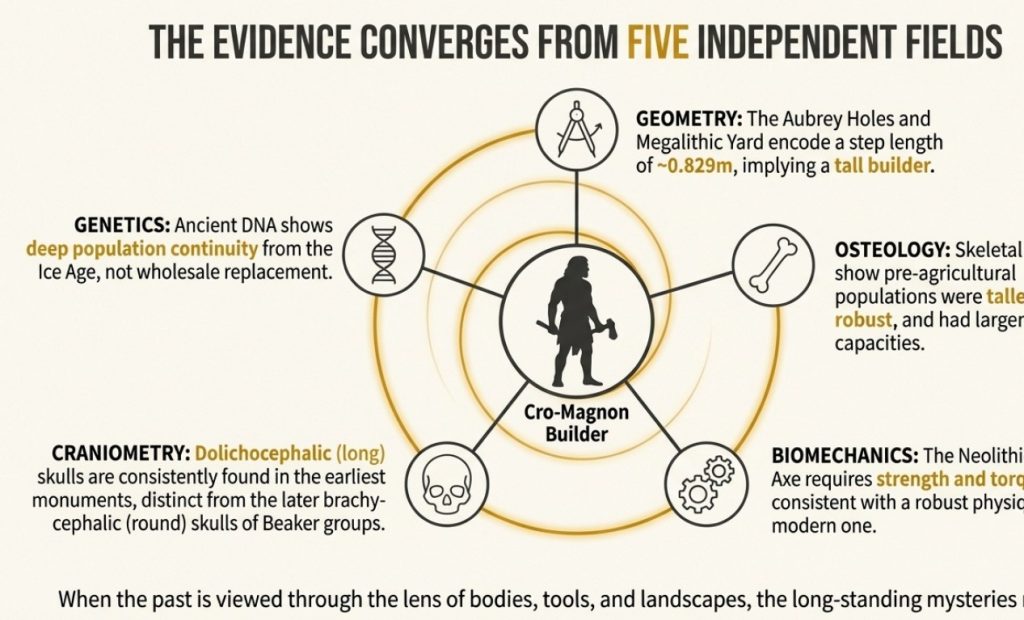

1. Introduction — Why This Debate Exists at All

The problem with prehistoric archaeology is not a lack of data.

It is a failure to ask the right questions.

For over a century, monuments such as Stonehenge, Avebury, and the great long barrows of Britain have been explained using labels: Neolithic, Beaker, Bronze Age, Western Hunter-Gatherer, Steppe ancestry. These terms sound authoritative, but they often function as placeholders rather than explanations. They tell us when something is assumed to belong — not who built it, how it was built, or whether the proposed builders were physically capable of the task.

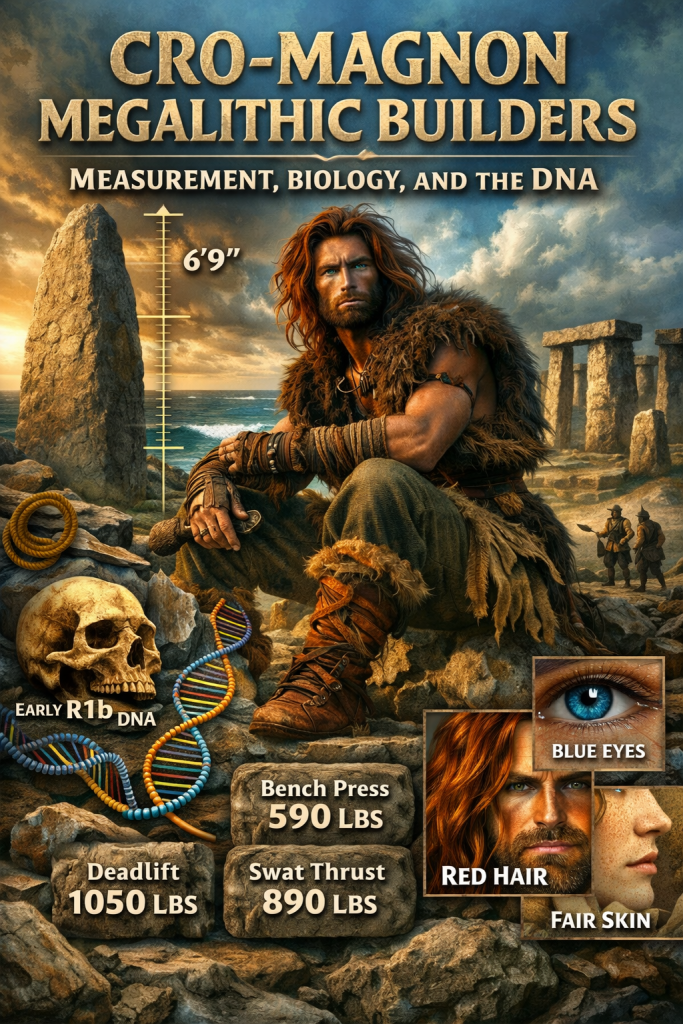

This article is not about mythical “giants,” nor is it an exercise in sensationalism. The word itself is misleading and has done more harm than good. The real issue is human scale.

Archaeology routinely interprets prehistoric monuments using modern human averages: modern height, modern strength, modern endurance, modern tools, modern landscapes. Yet the physical evidence increasingly shows that the people who built Europe’s earliest monumental architecture were not physically ordinary by modern standards. They were taller, more robust, stronger, and cognitively adapted to a world very different from our own.

Once that fact is acknowledged, a series of long-standing problems begins to resolve themselves:

- why monument construction timelines seem impossibly long

- why antler-pick explanations fail repeatedly

- why tool sizes appear “oversized”

- why step-based measurement systems emerge so cleanly

- why long barrows contain long-skulled individuals

- why later farming populations reuse, rather than originate, these sites

The question, therefore, is not “Were these people giants?”

It is:

Are modern humans the wrong baseline for understanding prehistoric builders?

This blog argues that they are.

By bringing together osteology, cranial morphology, tool ergonomics, biomechanics, embodied measurement, hydrology, and palaeogeography, a coherent picture emerges—one that archaeology has partially documented, occasionally acknowledged, but never fully integrated.

At the centre of that picture are Cro-Magnon–derived populations, rooted in the lost landscapes of northern Europe, whose physical characteristics match the monuments they left behind.

What follows is not speculation.

It is a reconstruction based on bodies, tools, geometry, and landscapes — the things that do not recalibrate, relabel, or quietly disappear when theories change.

2. Cro-Magnon ≠ Modern Human — Why Physiology Matters

One of the most persistent errors in prehistoric interpretation is the quiet assumption that all humans in the past were physically equivalent to us. This assumption is rarely stated outright, but it underpins almost every reconstruction: tool use, labour estimates, monument building rates, and even cognitive expectations.

The physical evidence does not support it.

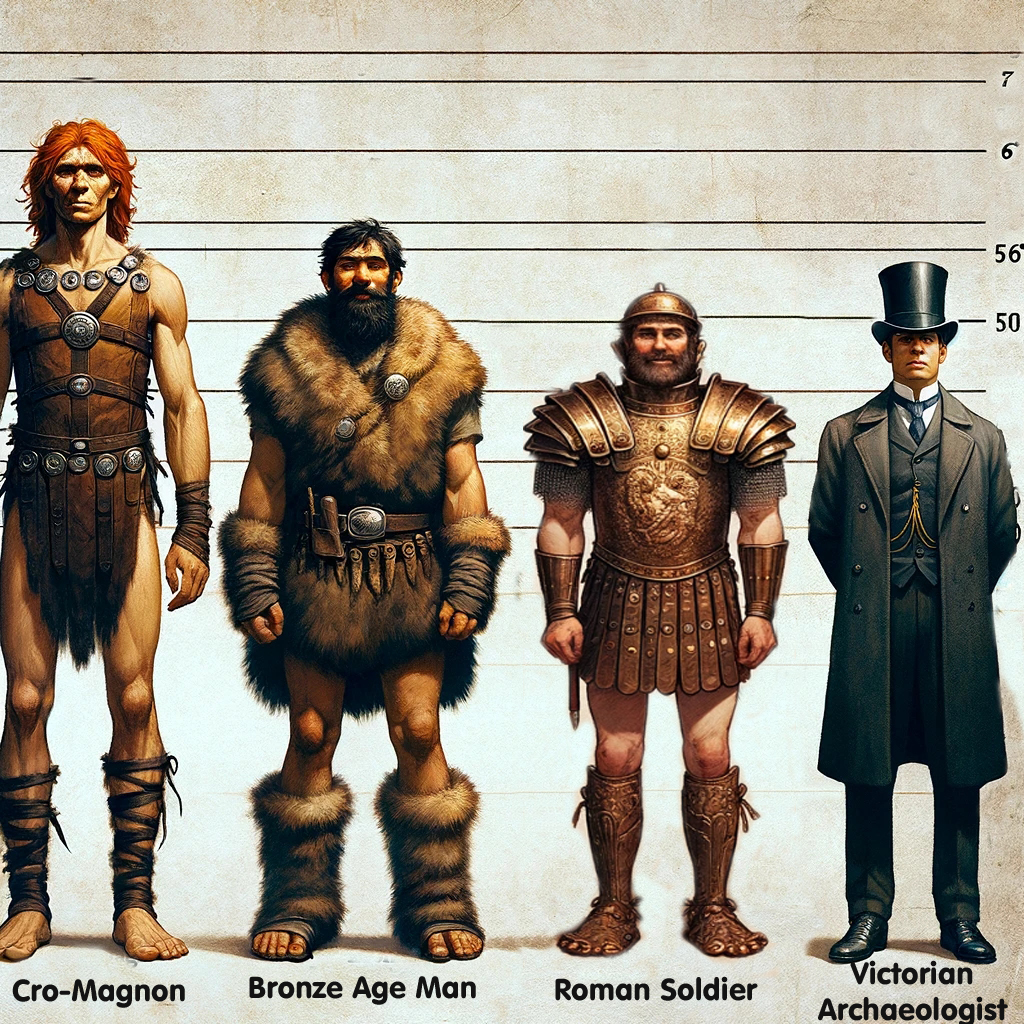

Upper Palaeolithic and early Mesolithic populations traditionally grouped under the term Cro-Magnon display a suite of anatomical traits that consistently diverge from later agricultural populations and from modern post-industrial humans.

These differences are not marginal.

They include:

- Greater average stature, particularly among males

- More robust skeletal frames, with thicker cortical bone

- Broader shoulders and longer limb proportions

- Higher muscle attachment development, indicating sustained heavy loading

- Larger average cranial capacity than modern Homo sapiens sapiens

Taken together, these traits describe a population adapted to high-energy expenditure, long-distance movement, and physically demanding tasks carried out over generations.

This is not surprising. Cro-Magnon populations lived in environments characterised by:

- cold or unstable climates

- protein-rich diets dominated by hunting, fishing, and aquatic resources

- constant mobility across large landscapes

- minimal reliance on agriculture or sedentary storage

In evolutionary terms, this favours size, strength, and endurance rather than reduction.

These patterns are well documented in Upper Palaeolithic and early Mesolithic osteological studies (e.g. Ruff 1994; Larsen 1995).

Agriculture Changed Bodies — It Did Not Improve Them

A crucial point often glossed over is that the transition to agriculture reduced human size and robustness, rather than enhancing it.

This is well established in bioarchaeology:

- average stature declines after the adoption of farming

- skeletal stress markers increase

- nutritional diversity decreases

- cranial capacity trends downward over time

These changes reflect dietary narrowing, increased disease load, and reduced physical demands, not biological advancement.

Later Neolithic and Bronze Age farming populations were not “better” versions of their predecessors — they were adapted to a different, more constrained way of life.

Using their bodies as the baseline for interpreting earlier monuments is, therefore, methodologically unsound.

Why This Matters for Monument Builders

If the builders of megalithic structures were:

- taller

- stronger

- more robust

- cognitively adapted to spatial and mechanical tasks

then many features that appear “mysterious” under modern assumptions become entirely reasonable:

- oversized tools cease to be anomalous

- heavy labour becomes sustainable

- short, thick tool handles make ergonomic sense

- step-based measurement systems become precise, not crude

- construction timelines shrink dramatically

The monuments do not demand mythical strength.

They demand pre-agricultural bodies.

The Error of Compression

Modern archaeology tends to compress tens of thousands of years of biological change into a single category: modern humans.

That compression is administratively convenient, but scientifically inaccurate.

Cro-Magnon populations were human, but they were not physically modern in the way we are. Their bodies reflect a different ecological niche, one that vanished as agriculture, sedentism, and later population influxes reshaped Europe.

Understanding who built the megaliths begins with accepting that their bodies were not our bodies.

Everything that follows — tools, measurement, labour, and landscape use — depends on that fact.

Suitable references

- Ruff, C. (1994). Morphological adaptation to climate in modern and fossil hominids. Yearbook of Physical Anthropology

- Larsen, C. (1995). Biological changes in human populations with agriculture. Annual Review of Anthropology

3. The Fatal Modern Assumption: Abstract Measurement

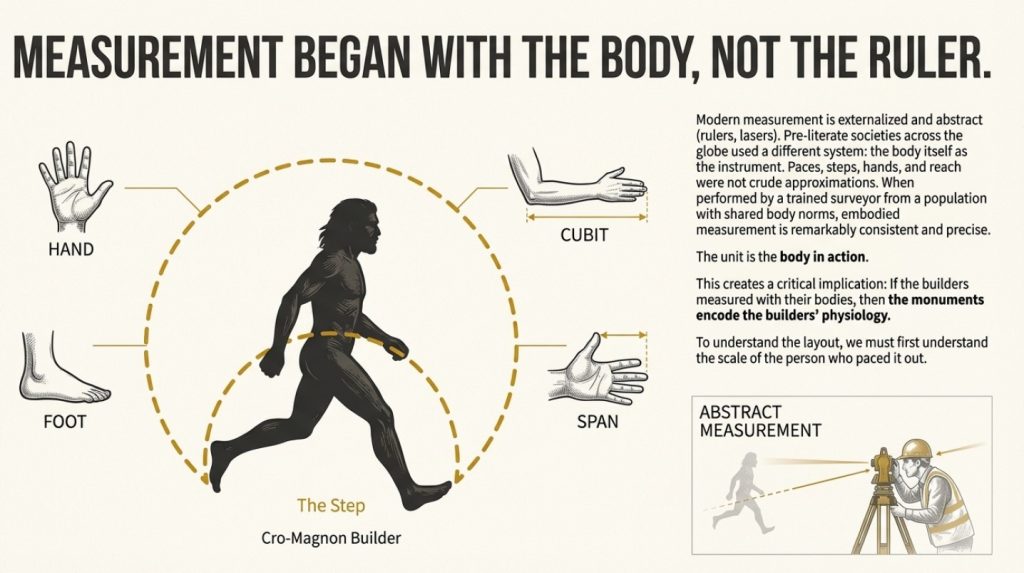

Once prehistoric builders are quietly assumed to be physically identical to modern humans, a second assumption follows almost automatically: that they measured the world in the same abstract way that we do.

This assumption is rarely examined — yet it is foundational to how monuments are interpreted.

Modern societies measure using externalised units: rulers, tapes, rods, laser surveys, and digital grids. These systems are detached from the body. They exist precisely because bodies differ and standards must be imposed from outside.

Prehistoric societies did not work this way.

Across ethnography, archaeology, and early historical records, the same pattern appears repeatedly: measurement begins with the body.

Hands.

Feet.

Elbows.

Paces.

Steps.

Reach.

These are not crude approximations. They are repeatable, trainable, and internally consistent when used by a stable population with shared body norms.

Embodied Measurement Is Not Guesswork

The idea that body-based measurement is imprecise is a modern prejudice.

In reality:

- a trained surveyor can reproduce step lengths with remarkable consistency

- deliberate pacing differs from casual walking

- ritualised or task-based gaits are consciously controlled

- repetition over short distances cancels cumulative error

This is why body-based units dominate early engineering traditions worldwide, from megalithic Europe to ancient Egypt and beyond.

The unit is not the body at rest—it is the body in action.

Body-based measurement systems are ethnographically universal in pre-literate societies (e.g. Kula 1966; Rottländer 1989).

Why This Matters for Megalithic Monuments

If prehistoric builders measured using their bodies, then the body becomes the measuring instrument.

That has immediate consequences:

- monument dimensions encode the builder’s physiology

- spacing reflects gait and reach, not abstraction

- regularity implies training, not symbolism

- precision implies repetition, not advanced mathematics

Crucially, this also means that modern bodies are the wrong tool for reverse-engineering prehistoric layouts.

A shorter, lighter, post-agricultural population will not reproduce the same results — not because the builders were mystical, but because the baseline has changed.

The Archaeological Blind Spot

Archaeology often acknowledges body-based units in passing, only to abandon them in favour of abstract explanations when patterns emerge that do not fit expectations.

When a monument resolves cleanly into a repeating unit, the assumption is often that:

- it must be symbolic

- or numerological

- or coincidental

Rarely is the most direct explanation tested:

What if the monument is laid out in human steps — but not modern ones?

Once this question is allowed, the focus shifts from abstract numbers to human biomechanics.

That shift is essential because it prepares us to understand one of the most critical pieces of evidence in Britain: the Aubrey Holes.

Suitable references

- Rottländer, R. (1989). Maß und Zahl in der Vorgeschichte

- Kula, W. (1966). Measures and Men

4. The Aubrey Holes — Measurement Frozen in Geometry

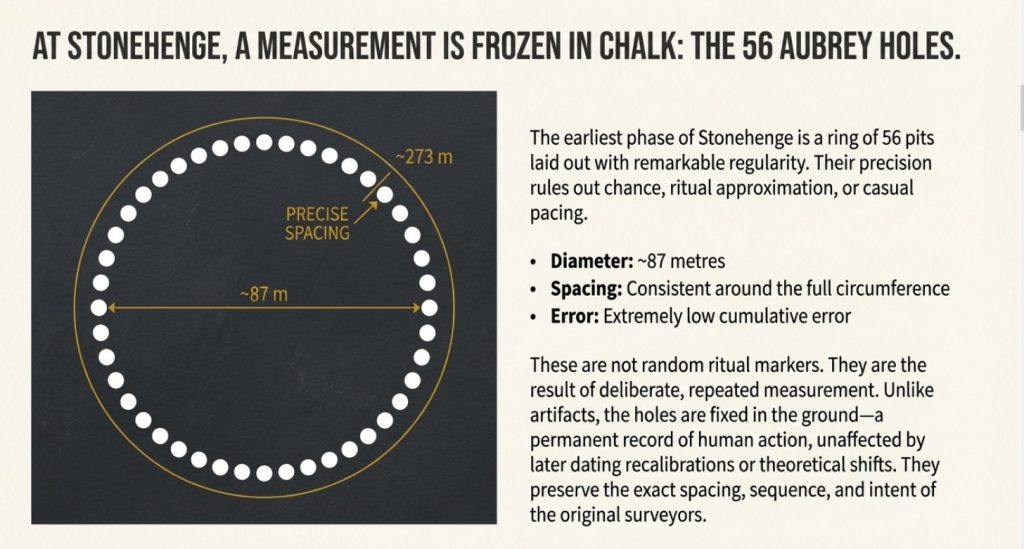

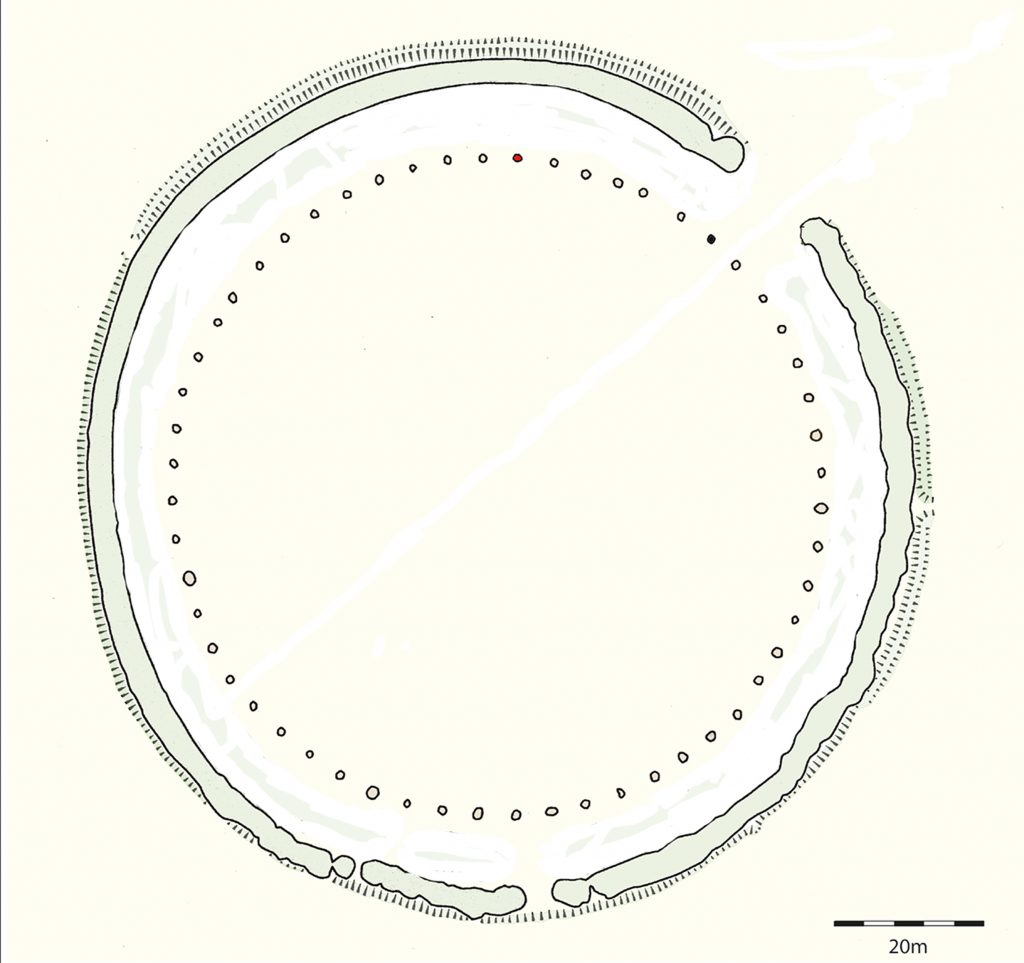

At Stonehenge, the earliest formal architectural phase is defined not by standing stones, but by a ring of 56 pits, traditionally known as the Aubrey Holes.

These features have been discussed for over three centuries, yet they remain poorly understood because they are usually treated as markers rather than as measurements.

That distinction matters.

What the Aubrey Holes Actually Are

The Aubrey Holes form a near-perfect circle approximately 87 metres in diameter, laid out with remarkable regularity given the absence of metal tools, written plans, or abstract surveying equipment.

What is often overlooked is this:

- the holes are evenly spaced

- the spacing is consistent around the full circumference

- cumulative error is extremely low

- the layout shows clear correction and control

This is not casual digging.

It is deliberate, repeated measurement.

Why Random or Symbolic Explanations Fail

If the Aubrey Holes were placed symbolically, ritually, or “by eye,” we would expect:

- variable spacing

- drift around the circle

- local clustering or correction only at the end

Instead, what we see is the opposite: controlled regularity from start to finish.

This immediately rules out:

- chance placement

- approximate pacing

- informal alignment

Something far more disciplined is at work.

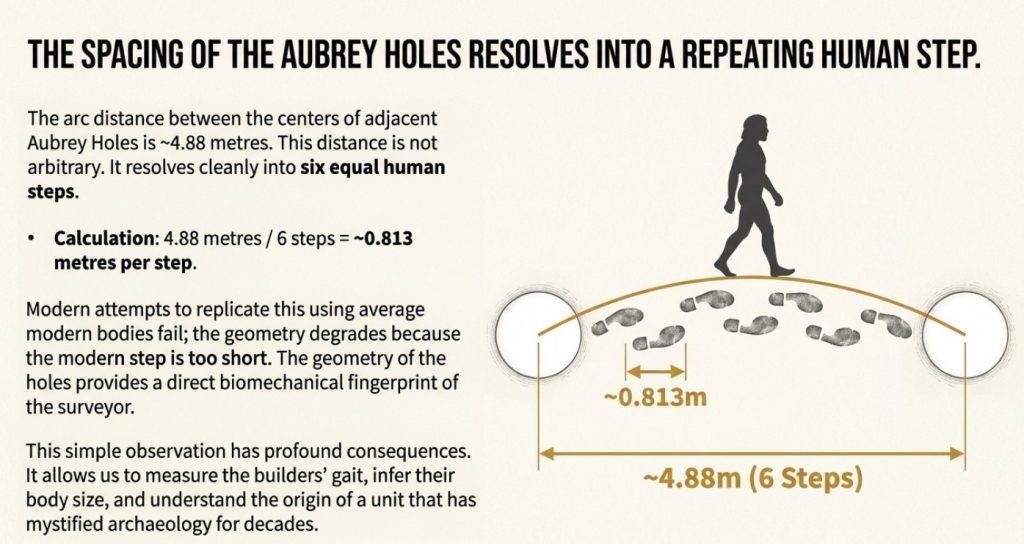

The Critical Observation: Step-Based Spacing

When the arc distance between adjacent Aubrey Holes is examined, it resolves cleanly into a repeating human-scale interval.

Not a rope length.

Not a rod.

Not an abstract unit.

A step.

More precisely:

- a deliberate, trained step

- repeated consistently

- over dozens of placements

Once recognised, this pattern becomes difficult to ignore.

Why Modern Replication Fails

Attempts to reproduce the Aubrey Hole spacing using modern average body dimensions consistently struggle to maintain accuracy around the full circle.

The reason is simple:

- modern average step length is shorter

- modern gait is optimised for comfort, not measurement

- modern bodies are post-agricultural and post-industrial

When the wrong body is used, the geometry degrades.

This has led many researchers to conclude — incorrectly — that the precision must be symbolic, mathematical, or coincidental.

The alternative explanation is far simpler:

The builders’ bodies were different.

The Aubrey Holes as Physical Evidence

Unlike artefacts that can be moved, redeposited, or reused, the Aubrey Holes are fixed in the ground.

They preserve:

- spacing

- sequence

- intent

- correction

They are not affected by:

- radiocarbon recalibration

- DNA model revision

- typological fashion

In that sense, they are among the most reliable pieces of evidence at Stonehenge.

They capture human action directly — frozen into chalk.

Measurements follow the surveyed dimensions published by Atkinson (1956) and Cleal et al. (1995).

Why This Matters

If the Aubrey Holes were laid out using deliberate human steps, then:

- the step length becomes measurable

- the body size of the surveyor can be inferred

- the origin of later “units” can be explained

- the monument stops being abstract

This takes us directly to the next problem archaeology has struggled with for decades:

The origin of the Megalithic Yard.

Suitable references

- Atkinson, R. J. C. (1956). Stonehenge

- Cleal, R., Walker, K., & Montague, R. (1995). Stonehenge in its Landscape

5. The Megalithic Yard Reframed — Not a “Mystery Unit”

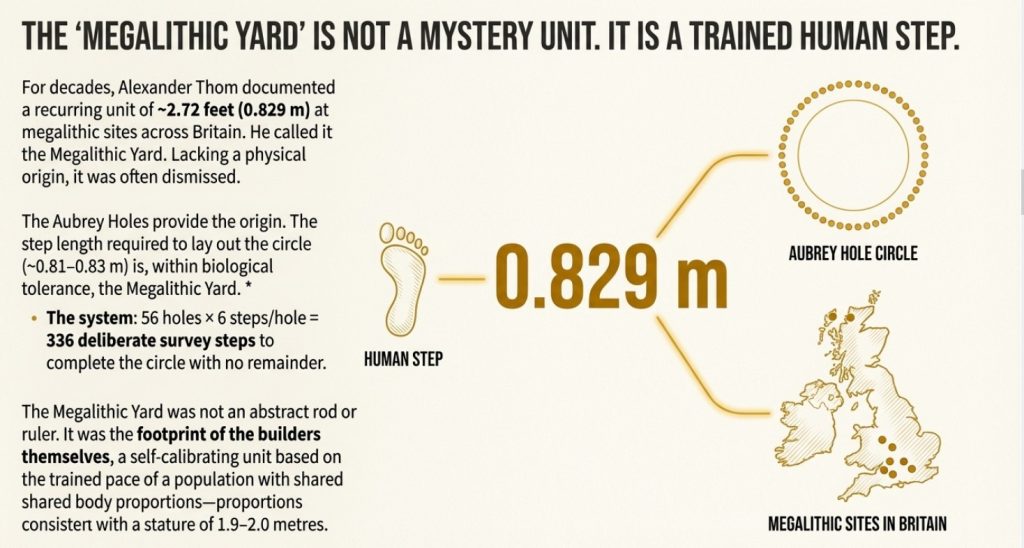

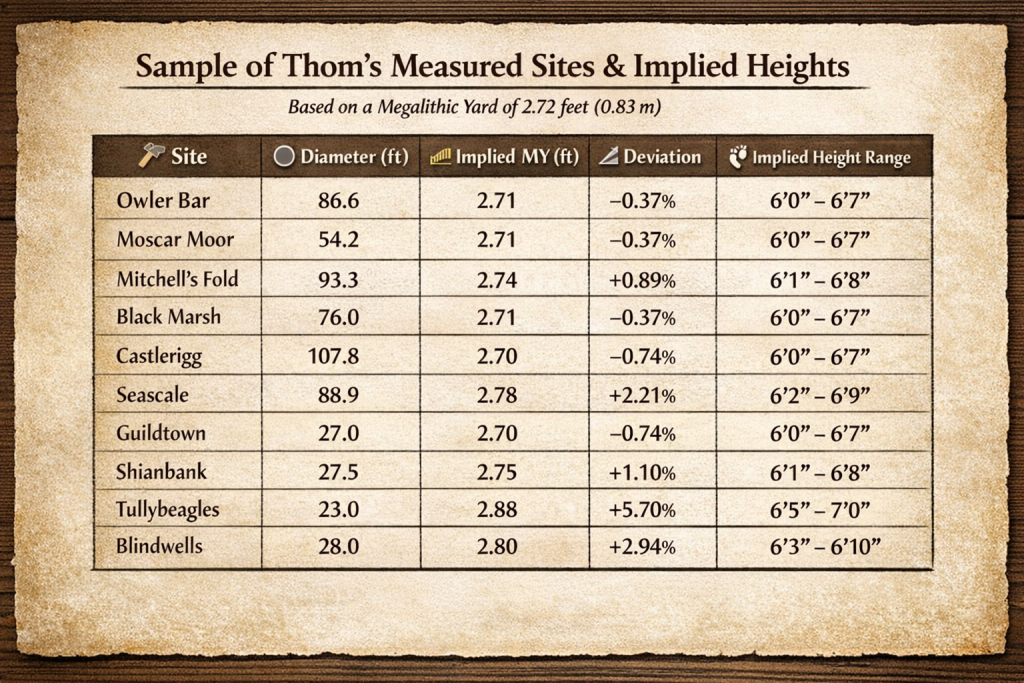

The Megalithic Yard has long been treated as an archaeological curiosity: widely measured, statistically persistent, yet conceptually uncomfortable. Alexander Thom demonstrated that a unit of approximately 2.72 feet (0.829 m) recurs across stone circles, flattened rings, ellipses, and stone rows throughout Britain and Atlantic Europe. That finding has never been seriously overturned. What Thom did not explain was where that unit originated.

The silence around its origin allowed a false assumption to harden: that the Megalithic Yard must have been an abstract standard, something equivalent to a measuring rod or conceptual unit imposed on the landscape. There is, however, no archaeological evidence for such a system. No rods, no standardised artefacts, no calibration objects, and no metrological infrastructure exist for Neolithic or early Mesolithic Britain.

What exists is physical geometry that demands a different explanation.

At Stonehenge Phase 1, the Aubrey Hole circle has a mean diameter of approximately 87.0 metres, giving a circumference of about 273.2 metres. Divided by the 56 Aubrey Holes, this produces a consistent arc spacing of roughly 4.88 metres between adjacent pits. That distance is not arbitrary. It resolves cleanly into six equal human steps, each of approximately 0.81–0.83 metres in length.

This matters because 0.82–0.83 metres is, within biological tolerance, the Megalithic Yard.

The correspondence is neither symbolic nor approximate. Six deliberate steps at ~0.82 m produce 4.92 m, six at ~0.813 m produce 4.88 m — exactly the observed spacing. Scaled around the full circle, this gives 56 × 6 = 336 deliberate survey steps, with no remainder and no cumulative drift. That level of closure cannot be produced by casual walking, visual estimation, or symbolic placement. It requires counted, deliberate pacing.

Once this is recognised, the Megalithic Yard stops being an abstract unit and becomes something far simpler: a trained human step.

Alexander Thom’s measurements (Thom 1967; Thom 1978)…

This also explains why Thom’s unit appears so consistently, despite the absence of physical standards. A paced step does not require rods or artefacts. It is self-calibrating within a population that shares similar body proportions and is trained to pace deliberately rather than walk casually. Minor local variation is expected, but large-scale coherence is preserved — exactly what Thom observed.

Biomechanics reinforces this interpretation. Deliberate survey steps are longer and more repeatable than everyday walking gait, typically scaling to about 42–45% of stature. The step length implied by the Aubrey Hole geometry therefore points to individuals in the 1.9–2.0 metre range, consistent with the robust, pre-agricultural bodies already documented osteologically. When modern average bodies are used, the geometry fails; spacing errors accumulate, and the circle degrades. The problem is not intelligence or technique — it is the wrong physiology.

Seen in this light, the Megalithic Yard does not represent lost mathematics or mysterious knowledge. It represents embodied measurement: space laid out by people who measured the land by moving through it, counting steps, correcting by eye, and repeating the process until precision was achieved.

Thom was right about the unit.

What was missing was the body.

The Megalithic Yard is not a mystery.

It is the footprint of the builders themselves, preserved in stone because it was first preserved in human movement.

Suitable references

- Thom, A. (1967). Megalithic Sites in Britain

- Thom, A. (1978). Megalithic Remains in Britain and Brittany

6. The Dating Mirage — Why C14 and DNA Mislead

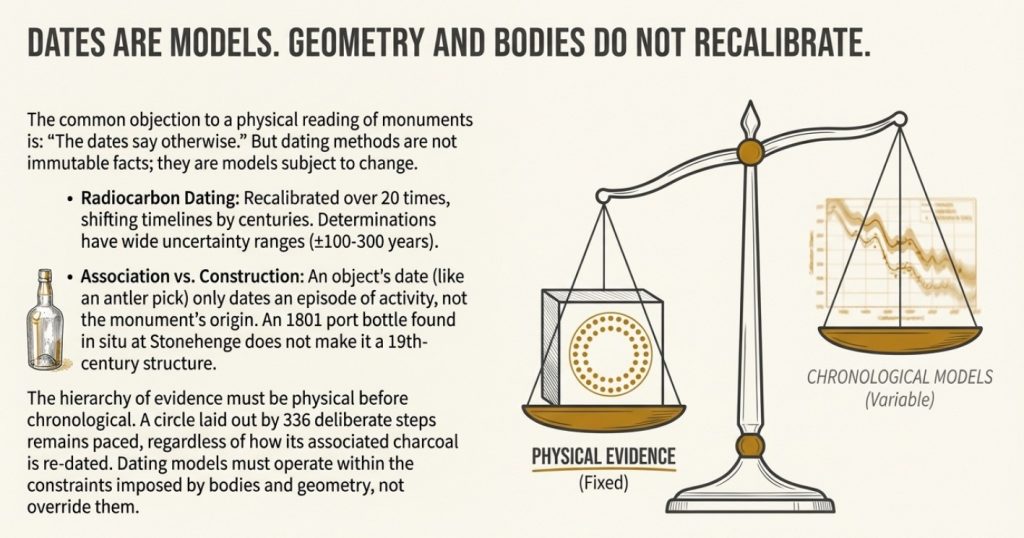

The objection most often raised against any physical or geometric reading of prehistoric monuments is familiar and automatic: “but the dates say otherwise.” Radiocarbon determinations, genetic chronologies, and typological phases are treated as fixed constraints, against which all other evidence must yield. The difficulty is that these dates are not fixed in the way geometry is fixed. They are models, and their instability is measurable.

Radiocarbon dating has been recalibrated more than twenty times since its introduction. Each revision alters the relationship between measured radiocarbon decay and calendar age, sometimes shifting archaeological contexts by centuries without any change to the material itself. Sites confidently assigned to specific periods in the mid-twentieth century now sit elsewhere on the timeline, not because the past has moved, but because the calibration curve has. Even within a single calibration, individual determinations commonly carry uncertainty ranges of ±100–300 years at 95 % confidence, and well-known plateaus compress long spans of time into overlapping date ranges. Precision is often implied where it does not exist.

That statistical instability would be manageable if the context were secure. Frequently, it is not.

At Stonehenge, William Hawley’s excavations in the 1920s documented an 1801 port bottle found in situ within the monument. Taken at face value and using the same logic often applied to prehistoric artefacts, this would require Stonehenge to be a nineteenth-century monument. Archaeologists correctly rejected that conclusion because they understood the principle involved: association does not equal construction. Objects can intrude into earlier deposits, be redeposited, or relate to later activity rather than the original layout. In situ does not mean foundational.

The same logical error is nevertheless repeated when antler picks, charcoal fragments, or isolated artefacts are used to anchor monument construction thousands of years earlier. Such finds can date an episode of activity, but they do not, by themselves, date the origin of the structure. Context is often assumed rather than demonstrated, and the dates derived inherit that assumption.

DNA chronologies compound the problem. Despite confident narratives of population replacement and cultural succession, fewer than 0.1 % of prehistoric genetic samples derive from skeletons that are both securely dated and securely associated with the monuments they are invoked to explain. The majority of genetic timelines are statistical reconstructions built from sparse, uneven datasets distributed across large geographic areas and long spans of time. These projections can suggest ancestry and relatedness, but they do not encode stature, step length, grip strength, gait, or the physical capacity required to execute the actions preserved in monument geometry.

This is where dating models collide with physical evidence.

Radiocarbon curves recalibrate. Genetic mutation rates are revised. Typological sequences are reorganised. But a circle laid out by repeated deliberate steps remains paced, regardless of how its associated artefacts are re-dated. A tool that demands exceptional grip strength remains demanding, irrespective of the cultural label attached to it. Bodies do not retroactively change scale, and geometry does not migrate over time.

The hierarchy of evidence is therefore physical before chronological. Dating models must operate within the limits imposed by bodies, tools, and landscapes, not override them. When dates conflict with what the physical evidence allows, the appropriate response is to reassess the model, not to dismiss the measurement.

Radiocarbon and DNA are useful analytical tools. They are not immutable facts.

Dates are models. Geometry and bodies do not recalibrate.

7. Cranial Evidence — Long Heads and Long Barrows

Long before genetics, calibration curves, or cultural labels entered archaeological discourse, prehistoric populations were classified by something far simpler and far harder to dispute: their bones. In particular, cranial morphology provided one of the earliest and most consistent signals that Britain’s earliest monument builders were physically distinct from later populations.

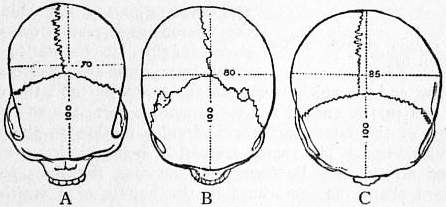

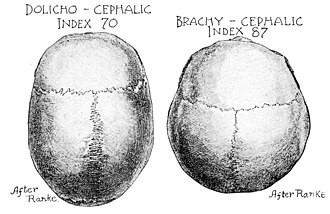

The distinction is not subtle. Human skulls vary measurably in shape, and one of the most robust metrics is the cranial index, the ratio of maximum skull breadth to maximum skull length. Values below roughly 75 define dolichocephalic (long-headed) forms; values above 80 define brachycephalic (round-headed) forms. These are not cultural categories. They are measurements.

Across Britain, a persistent pattern emerges in early excavation reports: dolichocephalic skulls dominate Neolithic chambered tombs and long barrows, while later round barrows and Beaker-associated burials increasingly contain brachycephalic or mesocephalic forms. This association was so consistently observed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that it entered archaeological shorthand: long heads for long barrows; round heads for round barrows.

One of the clearest examples comes from Belas Knap Long Barrow, excavated and published in detail by O. G. S. Crawford and others in the early twentieth century. The skulls recovered from Belas Knap, when viewed from above, show pronounced elongation, narrow breadth, and cranial indices firmly within the dolichocephalic range. These are not borderline cases. They are anatomically distinct from the rounder skull forms characteristic of later Bronze Age contexts.

What matters here is not taxonomy, but continuity of observation. These cranial distinctions were repeatedly recorded across multiple sites by different investigators, long before modern political or theoretical pressures entered the field. They were not invented to support a narrative; they were noticed because they were there.

The disappearance of this evidence from mainstream teaching did not occur because it was disproved. It happened because it became inconvenient. As archaeology moved toward models of continuity and cultural replacement without physical differentiation, cranial morphology posed a problem. Bones do not cooperate with tidy narratives. They either differ or they do not.

Crucially, the cranial evidence aligns with everything already established in the previous sections. Dolichocephalic skulls are associated with larger cranial capacities, which in turn correlate with the robust bodies, long limbs, and high-energy lifestyles documented for pre-agricultural populations. They sit comfortably alongside the step lengths implied by the Aubrey Hole geometry, the tool ergonomics requiring high grip strength, and the embodied measurement systems that precede abstraction.

By contrast, later Beaker-associated populations show a shift toward rounder skull forms, reduced robustness, and different burial architectures. This transition does not require invasion myths or replacement fantasies to explain it. It simply reflects population change over time, compounded by agriculture, diet narrowing, and later admixture.

The critical point is this: the people buried in long barrows were not physically identical to the people who later reused or repurposed these landscapes. The barrows preserve not just ritual practice, but the bodies of their builders. Those bodies are long-headed, robust, and consistent with the Cro-Magnon–derived populations already identified through physiology, biomechanics, and monument geometry.

Cranial morphology, therefore, provides an independent line of evidence that converges with the rest of the dataset. It does not stand alone, and it does not need to. It confirms what the measurements already imply: that Britain’s earliest monumental tradition belongs to a population physically distinct from later Bronze Age groups.

Cranial index thresholds follow standard physical anthropology definitions (e.g. Brothwell 1981; Bass 1995).

Bones do not recalibrate.

They do not migrate on typological timelines.

They remain exactly the shape they were when they were buried.

Suitable references

- Brothwell, D. (1981). Digging Up Bones

- Bass, W. (1995). Human Osteology

8. Cambridge Confirmation — Megalithic Builders ≠ Beaker People

The cranial distinction outlined in the previous section is not a relic of nineteenth-century typology, nor an artefact of early excavation bias. It has been independently confirmed in modern, peer-reviewed research, including work published through University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Press journals. What has shifted over time is not the skeletal evidence itself, but the interpretive framework applied to it.

Cambridge-linked analyses of Neolithic and Early Bronze Age human remains demonstrate a biological discontinuity between populations interred in chambered tombs and long barrows, and those associated with the Beaker complex (Sheridan 2010; Sheridan & Curtis 2004). The distinction is explicitly physical rather than cultural. Dolichocephalic (long-headed) skull forms dominate Neolithic chambered-tomb contexts, while brachycephalic (round-headed) forms are characteristic of Beaker-period burials, a pattern already recognised in early physical anthropology and now reaffirmed in modern synthesis.

This correspondence is not incidental. The association between long barrows and long-headed individuals was documented repeatedly across Britain and Atlantic Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including classic case studies such as Belas Knap (Crawford 1925; Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries 1864–1867). What modern Cambridge-published work demonstrates is that these early observations were not mistaken. They were simply unfashionable.

The implication is straightforward. If Beaker-associated populations were responsible for the construction of Britain’s major megalithic monuments, their skeletal signatures would be expected within the primary burial horizons of those monuments. They are not. Instead, Beaker-period remains appear as later insertions, consistent with reuse, adaptation, or occupation of landscapes already monumentalised by earlier populations (Sheridan & Curtis 2004).

This conclusion is reinforced when cranial morphology is considered alongside broader European datasets. Quantitative analyses of cranial form across the Neolithic–Bronze Age transition demonstrate measurable morphological shifts over time, rather than continuity, with long-headed forms dominant in earlier Neolithic contexts and rounder forms increasing later (Brace et al. 1993). These shifts align with changes in diet, subsistence, and population structure, not with the initial appearance of monumentality.

Cambridge research also highlights a second, frequently overlooked factor. The spatial distribution of Beaker artefacts across Europe does not match patterns expected from large-scale population replacement. Instead, Beaker material clusters strongly along river systems, estuaries, and coastal corridors, a behaviour consistent with exchange and contact networks rather than demographic swamping (Sheridan 2010). This mirrors the movement of other prestige goods, such as Alpine jade axes, which no serious archaeologist interprets as evidence for mass migration.

In this context, Beaker pottery functions as trade material rather than as a population marker. Objects move rapidly and widely; populations do not. Conflating artefact spread with monument authorship, therefore, introduces a category error.

When this evidence is set alongside monument geometry, step-based measurement, tool ergonomics, foot-scale biomechanics, and cranial form, the conclusion stabilises. Britain’s primary megalithic tradition belongs to a pre-Beaker population, physically distinct from later Bronze Age groups. That population closely corresponds to what has historically been described as Cro-Magnon-derived, without requiring claims of a separate species or speculative ancestry.

The role of Beaker groups is real but secondary. They enter landscapes already shaped, measured, and monumentalised by others. They leave material traces, but they do not originate the monumental system.

This is not a rejection of modern archaeology. It is a correction within it. The Cambridge evidence does not overturn early physical anthropology; it confirms it using modern analytical frameworks. The bones have not changed. Only the narrative has.

References cited in this section

- Sheridan, A. (2010). The Neolithisation of Britain and Ireland: the “Big Picture”. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 20(1), 89–105.

- Sheridan, A., & Curtis, N. (2004). The Neolithic–Early Bronze Age transition in Britain. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 14(1), 1–26.

- Brace, C. L., et al. (1993). Clines and clusters versus “race”. Journal of Human Evolution, 24, 1–43.

- Crawford, O. G. S. (1925). The Long Barrows of the Cotswolds.

- Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries, 2nd Series, Vol. 3 (1864–1867).

9. Trade, Not Invasion — The Beaker Distribution Problem

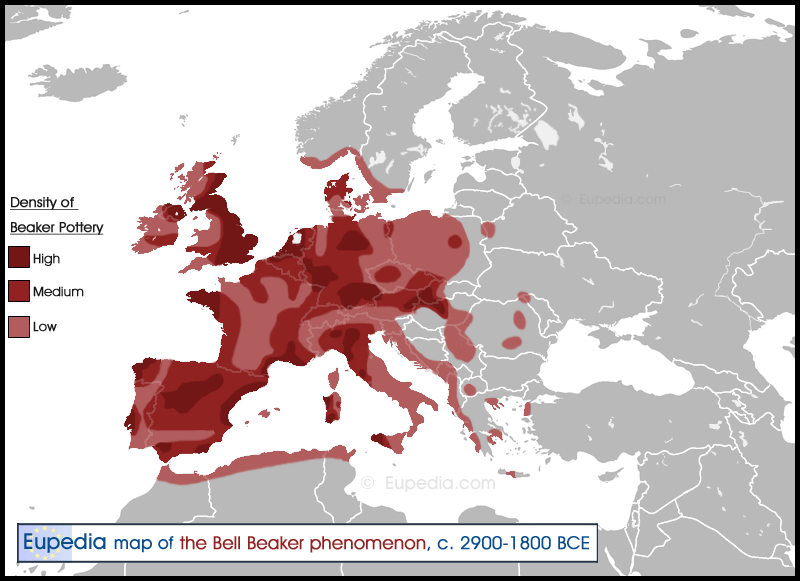

If the Beaker phenomenon represented a large-scale population replacement responsible for Britain’s megalithic monuments, its archaeological footprint would be broad and continuous. We would expect dense inland penetration, demographic saturation, and physical continuity between builders and Beaker burials. That is not what the evidence shows.

Instead, Beaker artefacts display a highly uneven spatial pattern. Across Britain and continental Europe, Beaker material clusters disproportionately along river systems, estuaries, and coastal corridors, with extensive inland regions showing sparse, episodic, or absent Beaker presence. This pattern has been documented repeatedly in large-scale syntheses of Beaker distribution (e.g. Needham 2005; Vander Linden 2007; Sheridan 2010). It is the spatial signature of exchange networks, not mass migration.

This distinction matters because population movement and object movement leave different archaeological fingerprints. Large-scale migration produces diffuse distributions across all habitable zones. Trade produces linear, network-driven patterns, focused along transport corridors where goods move efficiently. The Beaker record conforms closely to the latter.

A direct comparator is the distribution of Alpine jade axes. These objects originate from a handful of quarry zones in the western Alps yet appear across Atlantic Europe, including Britain and Ireland. Their movement is universally interpreted as trade and exchange rather than population displacement (Pétrequin et al. 2012). Beaker pottery exhibits an almost identical spatial logic: rapid spread, high visibility, and selective concentration along communication routes.

Chronology reinforces this interpretation. Beaker artefacts frequently appear after the construction of major monuments, inserted into landscapes already structured by long barrows, stone circles, and causewayed enclosures (Needham 2005; Sheridan & Curtis 2004). Where Beaker burials occur near earlier monuments, they are typically secondary, intrusive, or peripheral rather than foundational. The monuments are already there.

This undermines the common assumption that Beaker material culture equates to Beaker monument builders. Cultural packages can move far faster than people, particularly when prestige objects are involved. Treating the appearance of Beaker artefacts as evidence of authorship is therefore a category error — it confuses circulation with construction.

When this distributional evidence is set alongside earlier sections, the convergence is difficult to ignore. The bodies implied by monument geometry, step-based measurement, foot scale, tool ergonomics, and cranial morphology do not match later Beaker-associated populations. The monuments pre-exist widespread Beaker material. The artefacts arrive into an already monumentalised landscape.

None of this denies Beaker’s presence or influence. It places it correctly. Beaker groups interacted with existing populations, participated in exchange networks, and left a strong material signal — but they did not originate the megalithic tradition they encountered.

The Beaker distribution problem resolves cleanly once invasion assumptions are removed. What remains is a trade-driven network phenomenon layered onto an older demographic and monumental substrate.

Objects move easily.

People move slowly.

Monuments remember who was already there.

References cited in this section

- Needham, S. (2005). Transforming Beaker culture in north-west Europe: processes of fusion and fission. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 71, 171–217.

- Vander Linden, M. (2007). What linked the Bell Beakers in third millennium BC Europe? Antiquity, 81, 343–352.

- Sheridan, A. (2010). The Neolithisation of Britain and Ireland: the “Big Picture”. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 20(1), 89–105.

- Sheridan, A., & Curtis, N. (2004). The Neolithic–Early Bronze Age transition in Britain. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 14(1), 1–26.

- Pétrequin, P. et al. (2012). Jade: Objets-signes et interprétations sociales des jades alpins. Besanç

10. Brain Size and the “Efficiency” Excuse — When Biology Is Explained Away

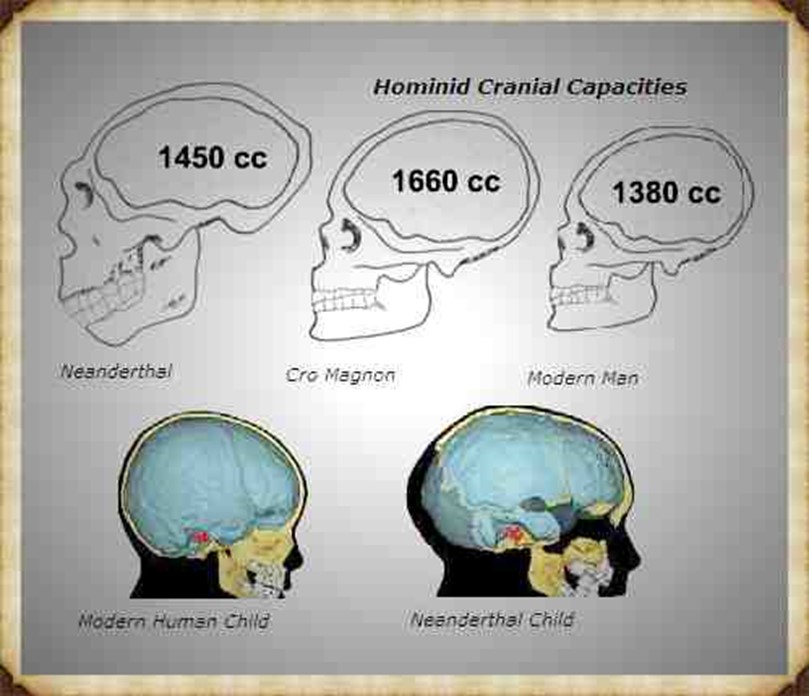

As the physical evidence for robust, tall, long-headed early populations has accumulated, a new explanatory reflex has emerged: the claim that larger brains do not matter, because smaller brains are supposedly “more efficient.” This idea now appears routinely in popular summaries and institutional science communication, often presented as settled understanding rather than speculation.

It is not settled. It is a post hoc narrative.

Upper Palaeolithic and early Mesolithic populations, including those traditionally described as Cro-Magnon, consistently show larger average cranial capacities than later agricultural populations. Values in the range of 1,550–1,650 cm³ are common in Upper Palaeolithic samples, compared with Holocene farming populations that average closer to 1,350–1,450 cm³ (Ruff et al. 1997; Henneberg 1988). This is not a marginal difference. It represents a reduction on the order of 10–15% in absolute brain volume.

That reduction correlates temporally with the adoption of agriculture, dietary narrowing, reduced mobility, and skeletal gracilisation. These correlations have been documented repeatedly in osteological studies and are not controversial (Larsen 1995; Ruff 2002). What is controversial is the attempt to reframe this reduction as adaptive “efficiency” without independent evidence.

No direct measure of cognitive efficiency exists in the archaeological record. Claims that smaller brains are “more efficient” are therefore unfalsifiable assertions, not empirical conclusions. They explain an observed reduction after the fact, rather than predicting it. By contrast, the relationship between brain size, body size, and energetic demand is well established. Larger, more active bodies require greater neural capacity for sensorimotor control, spatial navigation, and coordination. As activity levels and dietary diversity decline, neural demands do too.

This pattern is not unique to humans. In domesticated animals, including canids, brain size reduction is a consistent correlate of reduced behavioural demands. Wolves possess larger brains relative to body size than domestic dogs, not because wolves are less “efficient,” but because their ecological and behavioural requirements are greater (Kruska 1988; Kruska & Schott 1977). The direction of causation is clear: reduced demand leads to reduced neural investment.

The same logic applies to human populations transitioning from highly mobile, broad-spectrum subsistence to sedentary agriculture. Reduced ranging, simplified toolkits, and narrower diets lessen selective pressure on spatial cognition and sensorimotor integration. Brain size reduction follows. There is no independent evidence that this reduction reflects superior efficiency rather than lower functional demand.

This matters because attempts to downplay brain size differences are often used to neutralise the physical evidence discussed in earlier sections. Larger bodies, longer steps, heavier tools, and higher cranial capacities all point to populations operating at a different physical scale. Rather than addressing that scale directly, the “efficiency” argument seeks to dissolve it conceptually.

But the monuments do not cooperate with that manoeuvre.

The geometry preserved at Stonehenge Phase 1, the labour implied by large-scale ditching, the ergonomics of heavy stone tools, and the cranial forms found in long barrows all point toward populations with high physical and cognitive demand, not reduced ones. These demands are consistent with larger bodies and larger brains, not smaller, supposedly optimised ones.

The crucial point is that nothing in the archaeological record requires us to believe that smaller brains are better. The only thing required is that we accept the empirical sequence: as subsistence, mobility, and physical demands declined, so did average brain size. That is explanation enough.

Invoking “efficiency” does not add evidence. It removes discomfort.

When the physical record shows that earlier populations were larger, stronger, and more robust — cranially as well as skeletally — the responsible response is not to explain the difference away, but to account for it honestly.

Brains, like bodies, scale to demand.

When demand falls, so does size.

No narrative recalibration changes that.

References cited in this section

- Ruff, C. B., Trinkaus, E., & Holliday, T. W. (1997). Body mass and encephalisation in Pleistocene Homo. Nature, 387, 173–176.

- Henneberg, M. (1988). Decrease of human skull size in the Holocene. Human Biology, 60, 395–405.

- Larsen, C. S. (1995). Biological changes in human populations with agriculture. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24, 185–213.

- Ruff, C. B. (2002). Variation in human body size and shape. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31, 211–232.

- Kruska, D. (1988). Mammalian domestication and its effect on brain structure. Zeitschrift für Zoologie.

- Kruska, D., & Schott, A. (1977). Comparative quantitative investigations on brains of wild and domestic animals. Journal of Hirnforschung.

11. The Neolithic Power Axe — Scale, Strength, and Feasibility

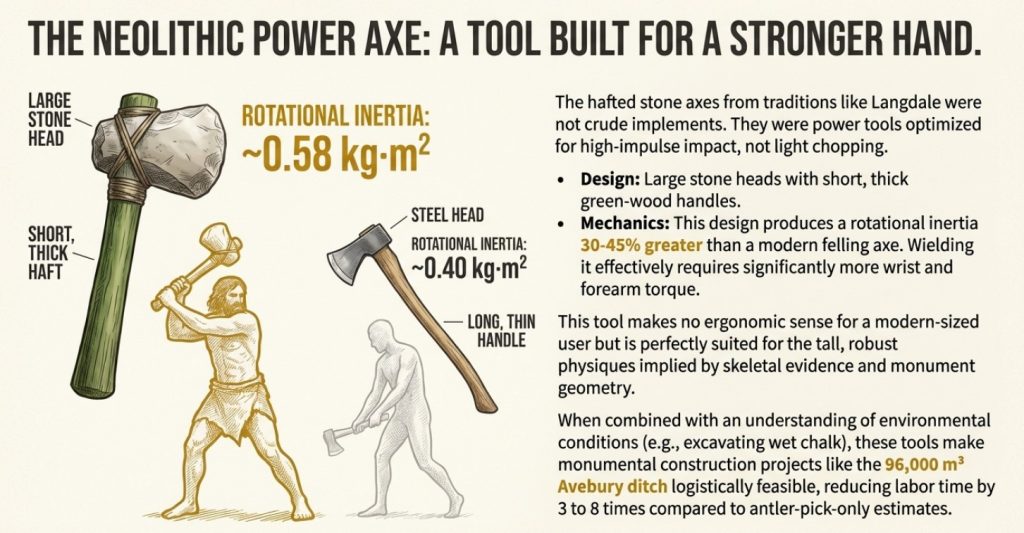

One of the most persistent errors in interpretations of early monument construction is the assumption that Neolithic stone axes were crude, inefficient tools. That assumption does not survive contact with fully hafted examples, experimental archaeology, or basic mechanics.

Hafted stone axes from the Langdale Group VI tradition, including complete or near-complete examples from Cumbria and adjacent regions, combine large stone heads, green-wood hafts, and short, thick handles (Bradley & Edmonds 1993; Edmonds 1995). These are not accidental proportions. They produce a tool optimised for power delivery, not light repetitive chopping.

The mechanical consequences are measurable. Control of an axe swing is governed by its rotational inertia, approximated by

I ≈ m r²,

Where m is the total mass of the tool, and r is the distance from the grip to the centre of mass. Modern steel felling axes typically weigh 2.0–2.3 kg, with balance points near 0.43 m, producing inertia values of 0.40 kg·m² (Coles 1979). By contrast, reconstructed Langdale-type hafted axes plausibly weigh 3.2–4.0 kg, with balance points around 0.38–0.40 m, yielding inertia values between 0.51 and 0.58 kg·m²—an increase of roughly 30–45 % in required wrist and forearm torque at the same swing cadence.

This is not theoretical. Experimental work on replicated stone axes consistently shows that these tools demand significantly greater grip strength, forearm mass, and wrist stability than modern axes, but deliver correspondingly higher impact energy per strike (Coles 1979; Whittle 1997). The short, thick handle geometry visible on surviving hafts concentrates control into the hand, favouring high-impulse blows rather than long-lever efficiency. That configuration only makes sense in the hands of large, robust users.

This directly intersects with labour feasibility. Earthworks such as the Avebury ditch involve excavation volumes on the order of ~96,000 m³. Traditional estimates based on dry antler-pick excavation alone typically exceed 15 labour-hours per cubic metre, producing implausible construction timelines (Whittle 1997). These estimates are known to be flawed because they exclude both realistic toolkits and environmental conditions.

Southern Britain’s chalk landscapes have high seasonal water tables. Experimental and geoarchaeological studies show that saturated chalk cuts and lifts more easily than dry chalk, and that spoil transport efficiency increases substantially under wet conditions (Allen & Gardiner 2002). When hafted stone axes and wooden spades are combined with seasonal waterlogging, conservative excavation rates drop to ~5 h/m³ even without deliberate hydraulic management. Where water is actively exploited—as ditch morphology and siting suggest—effective rates nearer ~2 h/m³ are entirely realistic.

That represents a three- to eight-fold reduction in labour time compared to antler-only assumptions. Under those conditions, monument construction becomes not exceptional but logistically routine for large, coordinated groups using heavy tools designed for power.

The significance of the power axe is therefore structural. It links body scale, tool design, and construction feasibility in a single physical system. Its mass and geometry cannot be reconciled with post-agricultural body norms, but they fit precisely with the tall, robust physiques implied by monument pacing, foot scale, and cranial morphology discussed earlier.

This is why the axe matters more than typology or dating labels. Its demands are immediate and mechanical. Either the builders had the strength and mass to wield such tools efficiently, or the tools—and the monuments built with them—do not make sense.

The axe removes that ambiguity.

References cited in this section

- Bradley, R., & Edmonds, M. (1993). Interpreting the Axe Trade. Cambridge University Press.

- Edmonds, M. (1995). Stone Tools and Society. Batsford.

- Coles, J. (1979). Experimental Archaeology. Academic Press.

- Whittle, A. (1997). Sacred Mound, Holy Rings. Oxbow.

- Allen, M. J., & Gardiner, J. (2002). A sense of place: Monuments and landscape in the Neolithic of southern Britain. Antiquity, 76, 161–172.

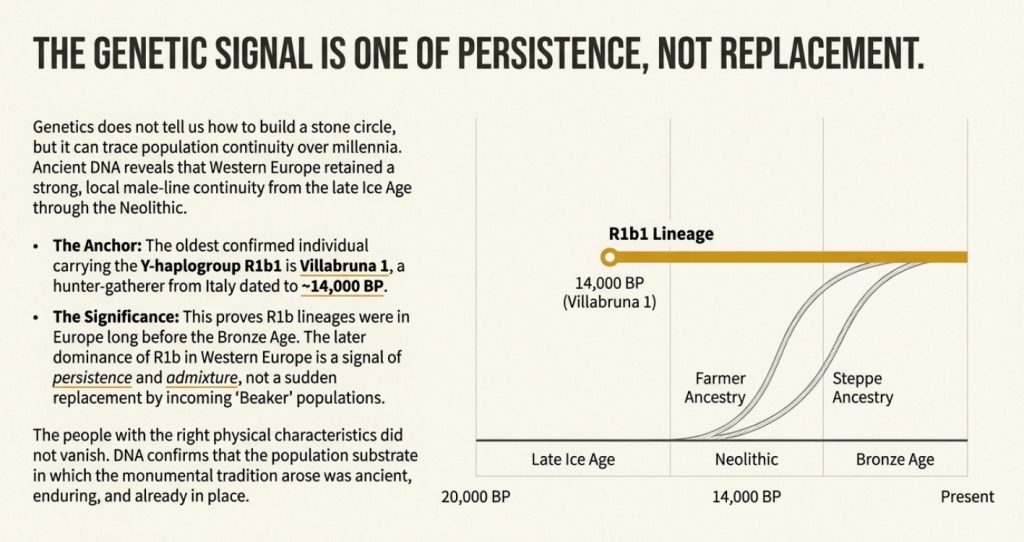

12. The Northern Genetic Continuum — R1b1 and Population Persistence

By this point, the argument has been established solely on physical grounds. Monument geometry implies large bodies and long steps. Tool ergonomics require exceptional grip strength. Cranial morphology identifies long-headed populations associated with early monuments. None of this depends on genetics. The role of DNA here is, therefore, limited and specific: to test population continuity, not to define builders.

When used in that restricted way, the genetic signal aligns with the physical evidence.

Across western and north-western Europe, Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b1 (and its downstream clades) shows deep temporal persistence. While modern distributions are complicated by later admixture, ancient DNA studies indicate that western Europe retained strong local male-line continuity from the late Upper Palaeolithic through the Mesolithic and into the Neolithic, with later inputs layered onto, rather than replacing, that substrate (Haak et al. 2015; Olalde et al. 2018).

Crucially, this continuity can now be anchored directly in the Ice Age. Villabruna 1 (I9030), an Epigravettian hunter-gatherer dated to approximately 14,000 BP, has been securely assigned to Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b1a (R-L754), making him the oldest confirmed R1b individual currently known (Fu et al. 2016; Posth et al. 2016). This establishes the presence of R1b lineages in Europe long before the Beaker or Bronze Age movements and removes the need to invoke a late wholesale replacement to explain its later dominance.

This is not a claim that “Cro-Magnons carried R1b1” in a simplistic or exclusive sense. Genetic lineages do not map neatly onto archaeological labels. What matters is that north-western Europe does not show evidence of wholesale male-line replacement at the point when monumental traditions emerge. Instead, the signal is one of persistence followed by admixture.

That distinction matters because it places limits on what later populations—such as Beaker-associated groups—can reasonably be said to have done. Where male-line continuity is strong, incoming cultural packages cannot automatically be equated with incoming builders. Pots can spread without people; people can mix without disappearing.

Crucially, the genetic evidence does not contradict the physical one. Tall stature, skeletal robustness, and long-headed cranial forms are all consistent with long-term hunter-gatherer or broad-spectrum forager populations maintaining continuity into the early Neolithic. The decline in robustness and cranial capacity occurs later, in line with dietary narrowing and agricultural dependence, not at the moment monuments first appear (Larsen 1995; Ruff 2002).

This sequence is visible genetically as well as physically. Early farmer ancestry enters Britain and Atlantic Europe gradually and unevenly, mixing with existing populations rather than replacing them outright (Olalde et al. 2018). The genetic transition mirrors the biological one: attenuation, not extinction.

It is, therefore, a mistake to treat DNA as an override mechanism that nullifies physical anthropology. Genetics does not tell us how tall people were, how far they walked in a day, or whether they could handle heavy stone tools. What it can tell us is whether the same populations remained present long enough for physical traditions to persist. In north-western Europe, the answer is clearly yes.

Seen in this light, R1b1 functions not as an identity marker, but as a continuity tracer. It indicates that the populations responsible for Britain’s earliest monumental traditions were not ephemeral or rapidly replaced. They endured, adapted, and absorbed later influences while retaining a detectable genetic footprint.

This prepares the ground for the next section. If population continuity exists, then secondary traits—such as pigmentation—can legitimately be examined as residual signals rather than as determinative markers. Without this genetic context, pigmentation would indeed feel arbitrary. With it, the sequence holds.

DNA does not explain the monuments.

But it confirms that the people who could build them did not vanish when the landscape changed.

References cited in this section

- Haak, W., et al. (2015). Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe. Nature, 522, 207–211.

- Olalde, I., et al. (2018). The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of north-west Europe. Nature, 555, 190–196.

- Fu, Q., et al. (2016). The genetic history of Ice Age Europe. Nature, 534, 200–205.

- Posth, C., et al. (2016). Palaeogenomics of Upper Palaeolithic Europe. Nature Communications, 7, 12727.

- Larsen, C. S. (1995). Biological changes in human populations with agriculture. Annual Review of Anthropology, 24, 185–213.

- Ruff, C. B. (2002). Variation in human body size and shape. Annual Review of Anthropology, 31, 211–232.

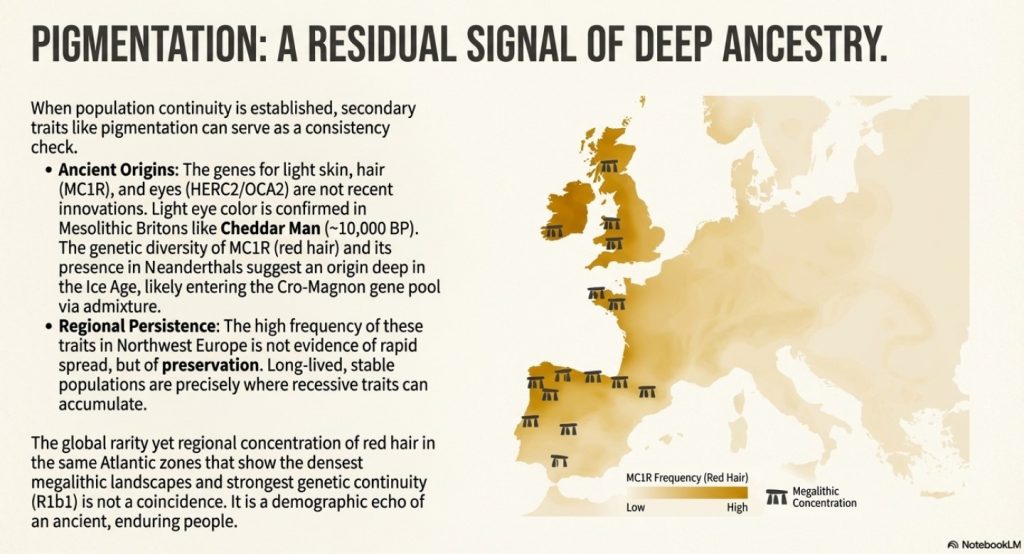

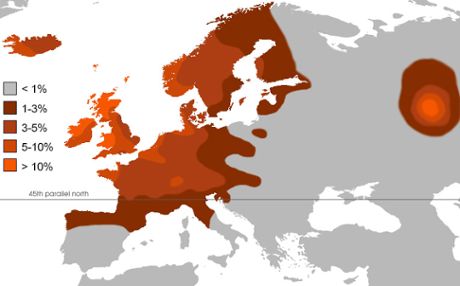

13. Pigmentation as an Inherited Ice-Age Signal

If population continuity can be demonstrated physically and genetically, then pigmentation can be examined not as a causal factor but as a residual biological signal. Hair and skin colour do not explain monument building, but they can reflect the deep history of populations in which monument builders were embedded. When used cautiously, pigmentation serves as a consistency check rather than an independent claim.

Red hair is associated with variants of the MC1R gene on chromosome 16 (Rees 2003; Harding et al. 2000). These variants are autosomal, not Y-linked, and are therefore not caused by any Y-chromosome haplogroup. However, the common presentation of red hair as a late, isolated mutation spreading rapidly through north-west Europe is biologically implausible. MC1R is unusually polymorphic in humans, and European MC1R diversity is far too high to be explained by a single recent origin event (Harding et al. 2000; Rees 2003). The problem, therefore, is not how such traits suddenly arose, but why they survived and intensified in specific regions.

This is where the book’s “practical solution” matters: admixture provides a mechanism that does not require miracles. Neanderthals carried functional variants at MC1R consistent with lighter pigmentation, demonstrating that reduced pigmentation existed in western Eurasia prior to later Holocene population histories (Lalueza-Fox et al. 2007). Cro-Magnon populations interbred with Neanderthals repeatedly during the Upper Palaeolithic, and modern Europeans retain measurable Neanderthal introgression. In that context, pigmentation-related variants could have entered Cro-Magnon-derived populations early and persisted as part of a deeper Ice-Age inheritance rather than appearing late as a sudden innovation (Lalueza-Fox et al. 2007; Rees 2003).

Once present, the fate of these variants depended less on “rapid spread” and more on population structure. In much of Europe, later demographic turnover diluted early signals. In contrast, north-west Atlantic Europe shows strong evidence for long-term local persistence with later admixture rather than immediate replacement, which is precisely the demographic environment in which recessive traits can accumulate to unusually high local frequencies (Jobling & Tyler-Smith 2017; Olalde et al. 2018). Under those conditions, red hair and very light skin do not need to be newly created; they need only be preserved and amplified within enduring populations.

The modern distribution reflects this history. Red hair remains globally rare yet regionally concentrated, with its highest frequencies in Ireland, western Britain, and adjacent Atlantic regions. These are the same regions that show the strongest persistence of Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b1 and the densest early megalithic landscapes. The relationship is not causal but demographic: long-lived populations preserve ancient traits, and Y-line continuity functions as a tracer of that persistence (Jobling & Tyler-Smith 2017; Olalde et al. 2018).

Not all red-haired individuals belong to R-lineage populations. A minority occur in regions where R haplogroups are rare, reflecting later diffusion through admixture rather than independent origin. This is entirely expected under the same model. Later prehistoric and early historic movements redistributed pigmentation traits across northern Europe, but redistribution is not the same as origin; secondary spread cannot explain the primary Atlantic centre of gravity.

Pigmentation, taken alone, proves nothing. But when read alongside skeletal morphology, tool ergonomics, monument geography, and genetic continuity, it reinforces the same conclusion reached repeatedly from independent lines of evidence. The people capable of constructing Europe’s earliest monuments did not vanish with the Ice Age. They persisted, adapted, and carried elements of their Ice Age biology into the present.

References cited in this section

- Harding, R. M. et al. (2000). Evidence for variable selective pressures at MC1R. American Journal of Human Genetics, 66, 1351–1361.

- Rees, J. L. (2003). The genetics of sun sensitivity in humans. American Journal of Human Genetics, 75, 739–751.

- Lalueza-Fox, C. et al. (2007). A melanocortin 1 receptor allele suggests varying pigmentation among Neanderthals. Science, 318, 1453–1455.

- Olalde, I. et al. (2018). The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of north-west Europe. Nature, 555, 190–196.

- Jobling, M. A. & Tyler-Smith, C. (2017). Human Y-chromosome variation and population history. Nature Reviews Genetics, 18, 485–497.

14. Eye Colour and Deep Ancestry in North-West Europe

Eye colour provides an apparent test of the continuity model developed in the preceding sections. Unlike hair pigmentation, which involves multiple interacting variants, light eye colour in Europe is primarily controlled by variation at the HERC2–OCA2 locus on chromosome 15 (Eiberg et al. 2008). This genetic architecture is comparatively narrow, making eye colour less sensitive to environmental plasticity and less prone to repeated independent origin. For that reason, its geographic pattern is especially informative.

As with hair colour, eye colour is inherited in an autosomal manner from both parents. It is not linked to the Y-chromosome and is not caused by any haplogroup. Its value lies instead in persistence: where populations endure, rare traits can survive and intensify; where replacement occurs, they are diluted or lost.

The critical issue is chronology. Claims that blue or green eyes emerged only in the Neolithic or Bronze Age are contradicted by ancient DNA. Mesolithic individuals from north-west Europe already carried the derived HERC2/OCA2 allele associated with light eye colour, demonstrating that the trait predates agriculture and later demographic shifts (Olalde et al. 2014). The most widely cited example is Cheddar Man, dated to approximately 10,000 years BP, whose genome indicates blue or green eyes despite his clear pre-agricultural hunter-gatherer context (Brace et al. 2019).

This evidence places light eye colour firmly within Ice-Age-derived populations of Britain. It was not introduced by early farmers, Beaker-associated groups, or Bronze-Age movements. As with MC1R variants discussed in Section 13, the question is not when eye colour first appeared, but where populations remained stable enough for it to persist.

The modern distribution reflects that same demographic logic. Blue and green eyes reach their highest frequencies in north-west Europe, particularly around the North Sea and Atlantic façade, and decline sharply outside this zone. This pattern mirrors regions of strong population persistence rather than routes of late prehistoric expansion. Later movements redistributed the trait more widely across Europe, but they did not erase its original centre of gravity (Walsh et al. 2017; Jobling & Tyler-Smith 2017).

Importantly, this signal operates independently of Y-DNA lineages. Cheddar Man’s paternal haplogroup differs from those dominant in later Atlantic populations, yet the eye-colour trait persists across that transition. This reinforces the central point developed throughout the book: pigmentation traits predate later haplogroup dominance and are best understood as inherited features preserved by continuity, not markers introduced by population replacement.

Read together with Section 13, eye colour strengthens the same conclusion rather than introducing a new one. Hair, skin, and eye pigmentation all point to an ancient origin combined with regional survival. These traits did not arise suddenly, nor were they imposed by later populations. They endured where populations endured.

Pigmentation, therefore, functions as a residual map of deep ancestry. It does not identify monument builders individually, but it confirms that the populations capable of building monuments were rooted in the same landscapes long before and long after those monuments were raised.

References cited in this section

- Eiberg, H. et al. (2008). Blue eye color in humans may be caused by a perfectly associated founder mutation in a regulatory element located within the HERC2 gene inhibiting OCA2 expression. Human Genetics, 123, 177–187.

- Olalde, I. et al. (2014). Derived immune and ancestral pigmentation alleles in a 7,000-year-old Mesolithic European. Nature, 507, 225–228.

- Brace, S. et al. (2019). Ancient genomes indicate population replacement in Early Neolithic Britain. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 3, 765–771.

- Walsh, S. et al. (2017). The HIrisPlex system for simultaneous prediction of hair and eye colour from DNA. Forensic Science International: Genetics, 16, 261–268.

- Jobling, M. A. & Tyler-Smith, C. (2017). Human Y-chromosome variation and population history. Nature Reviews Genetics, 18, 485–497.

Synthesis: Bodies, Continuity, and the Shape of the Past

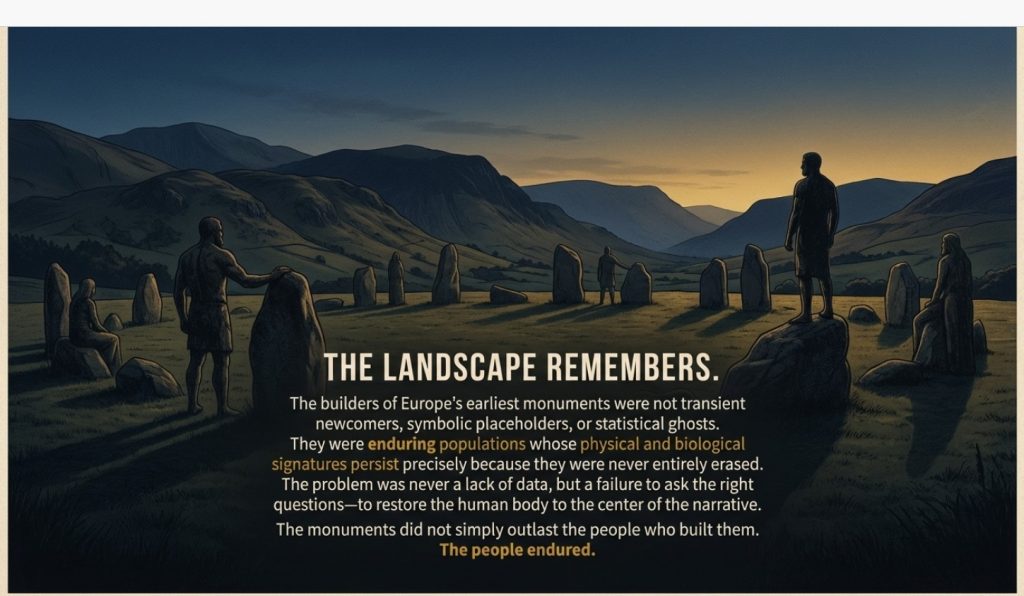

Taken together, the evidence assembled here resolves a problem that has long been obscured by disciplinary boundaries rather than a lack of data. Europe’s earliest monumental landscapes did not emerge from abstract cultural phases or statistical populations. They emerged from people—real bodies operating within physical limits, using tools whose scale and mechanics still survive, laying out spaces whose geometry remains fixed in the ground.

The argument begins with constraint. Monument geometry implies deliberate pacing and consistent embodied measurement. Tool ergonomics require grip strength and leverage incompatible with gracile physiques. Ditch volumes demand sustained labour capacity at a scale that cannot be reconciled with populations already showing biological attenuation. These are not interpretations; they are physical facts.

Those constraints narrow the field sharply. Neanderthals are excluded by chronology and stature. Later agricultural populations are excluded by declining robustness, reduced cranial capacity, and biomechanical mismatch. The only populations that fit the required physical envelope are Cro-Magnon–derived Upper Palaeolithic Europeans—tall, long-limbed, mechanically robust humans adapted to demanding environments long before agriculture reshaped biology.

Genetics does not overturn this conclusion. When used correctly, it reinforces it. Ancient DNA demonstrates continuity rather than wholesale replacement across north-western Europe from the Late Upper Palaeolithic into the Neolithic, with later admixture layered onto an enduring substrate. The presence of R1b lineages in Ice-Age Europe confirms persistence, not origin, and removes the need to invoke late demographic miracles to explain either monument builders or modern population structure.

Pigmentation then falls into place, not as an explanatory driver, but as a residual signal of that continuity. Hair colour, skin tone, and eye colour do not appear suddenly, nor do they spread implausibly fast. They reflect ancient variation preserved where populations endured and diluted where they did not. Neanderthal admixture provides a biologically natural mechanism for early pigmentation diversity; long-term regional stability explains its modern concentration. Cheddar Man confirms antiquity. Atlantic Europe confirms persistence.

At no point does any single line of evidence carry the argument alone. The strength lies in convergence. Geometry, biomechanics, osteology, genetics, and pigmentation all point in the same direction independently. None requires special pleading. None depends on speculative leaps. Each simply removes implausible alternatives until only one population history remains consistent with the ground beneath our feet.

What emerges is not a radical reimagining of prehistory, but a correction of emphasis. The past has been made strange not by evidence, but by abstraction. When bodies are restored to the centre of the narrative, many long-standing problems dissolve. The builders of Europe’s earliest monuments were not transient newcomers, symbolic placeholders, or statistical ghosts. They were enduring populations whose physical and biological signatures persist precisely because they were never entirely erased.

The monuments did not outlast the people who built them.

The people endured—and the landscape still remembers them.

Podcast

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed