Prehistoric Herefordshire Canals (Dykes)

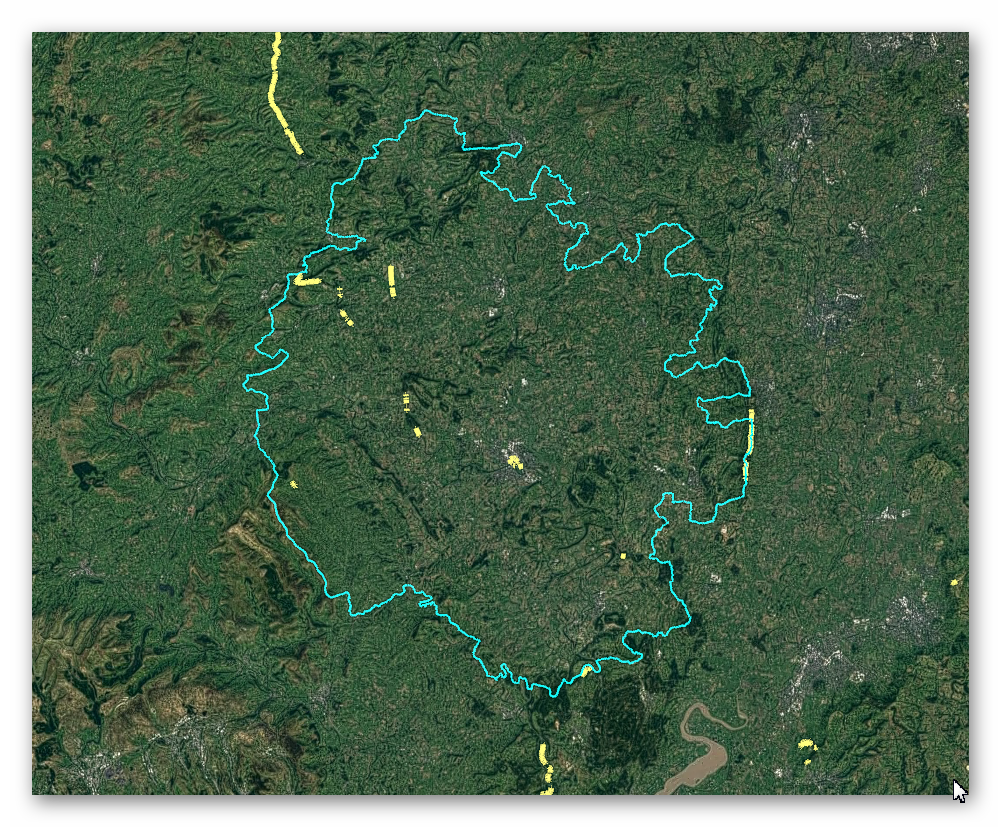

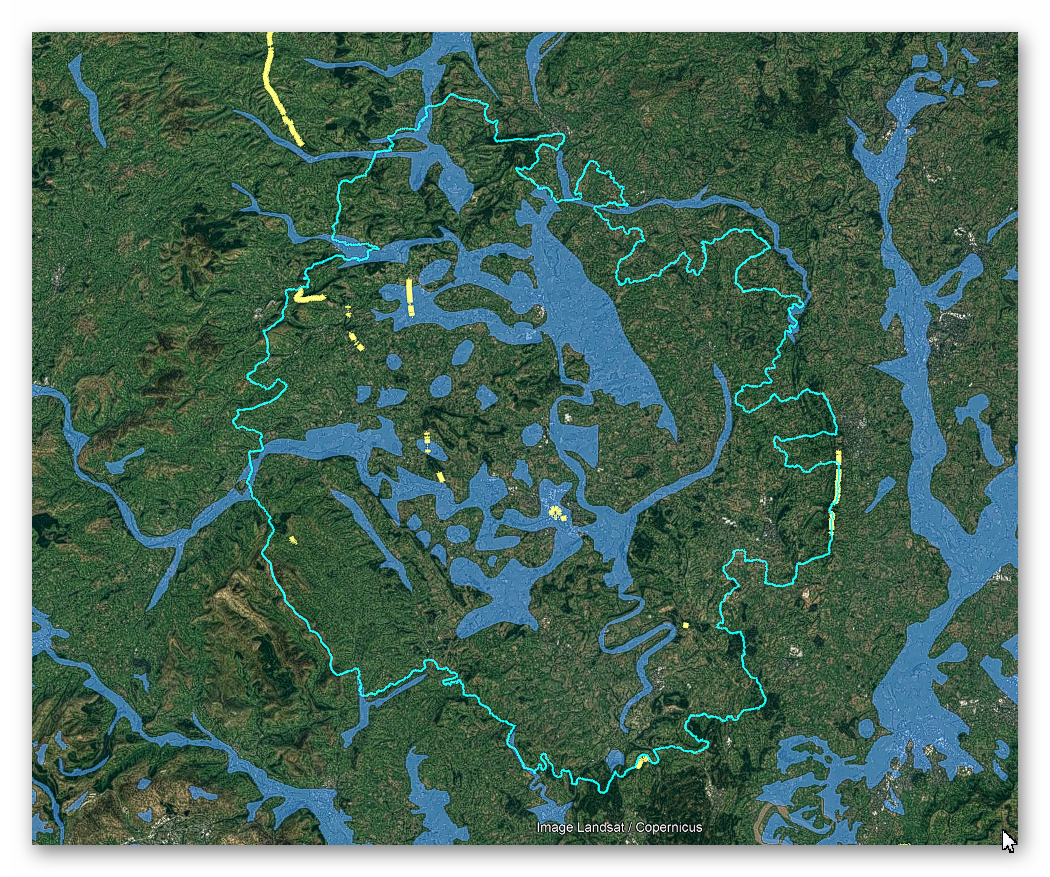

GE Map of Prehistoric Herefordshire Canals (Dykes)

Old Map

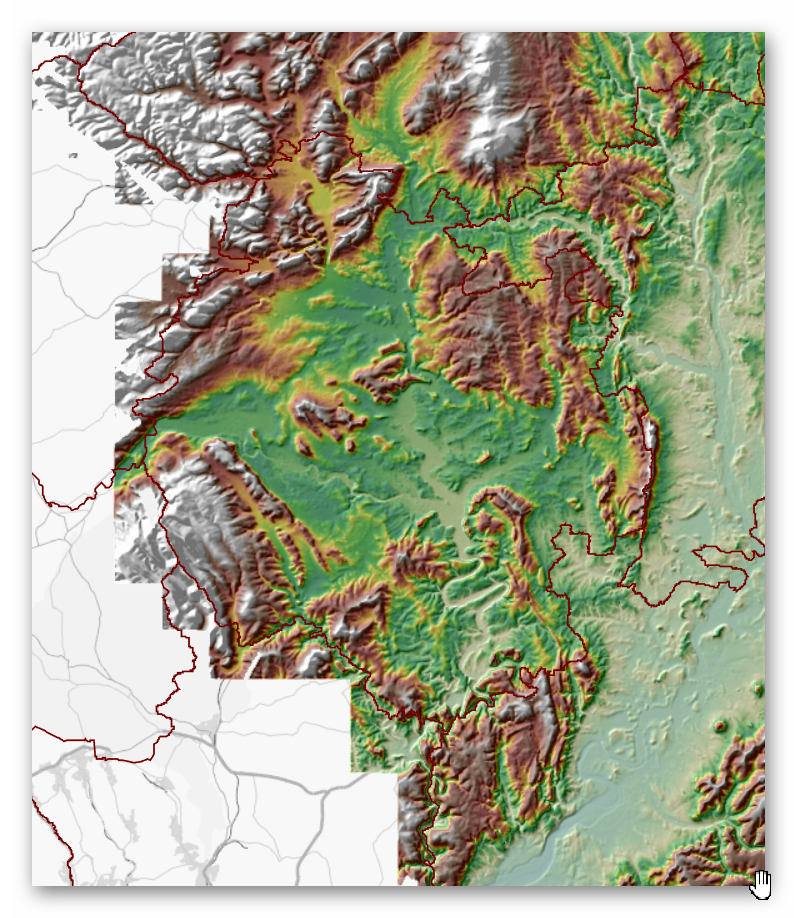

Geological Landscape

Landscape/Terrain

Database of DYKES (Linear Earthworks) in Herefordshire

(Click the ‘HE Entry Ref: Number’ (if blue) for more details and Maps)

| Name | HE Entry Ref: | NGF | Length (m) | Overall Width (m) | Ditch Width (m) | Bank Width (m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Offa's Dyke: Rushock Hill section, extending 1630yds (1490m) E to Kennel Wood | 1001731 | SO 29562 59529 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: the section extending 165yds (150m) N from Berry Wood | 1001732 | SO 32395 58700 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: the section 630yds (580m) long W of Lyonshall | 1001733 | SO 32790 55995 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: the section E of Garden Wood, extending SE 85yds (80m) | 1001734 | SO 33139 55387 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: section NW of Holme Marsh extending 615yds (560m) to the railway | 1001735 | SO 33493 55016 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: Upperton Farm, two sections extending 195yds (180m) and 370yds (340m) S from Yazor | 1001736 | SO 39458 46771 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: the section extending 230yds (210m) N and S of the Old Barn near Kenmoor Coppice (SE of Bowmore Wood) | 1001737 | SO 39505 45557 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: the section extending 950yds (870m) N and S of Big Oaks | 1001738 | SO 40636 43192 | ||||

| Row Ditch (entrenchment) | 1001780 | SO 51018 39403 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: the section extending 300yds (270m) crossing the railway W of Titley Junction | 1003776 | SO 32424 57935 | ||||

| The Shire Ditch See also WORCESTERSHIRE 244 | 1003812 | SO 76911 44047 | ||||

| Dyke on S side of Yatton Wood | 1005341 | SO 62846 29494 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: section S of Riddings Brook on Herrock Hill | 1005358 | SO 28087 60352 | ||||

| North Herefordshire Rowe Ditch | 1005382 | SO 38076 58720 | ||||

| Offa's Dyke: the section N of Upperton Farm, extending 175yds (160m) | 1005525 | SO 39434 47134 | ||||

| Hereford city walls, ramparts and ditch | 1005528 | SO 50721 39884 | ||||

| Craswall Priory, associated building remains, pond bays and hollow ways | 1014536 | SO 27546 37442 | ||||

| Hertfordshire Grim's Ditch: 1150m long section between Shire Lane and Kiln Road | 1021203 | SP 92117 08977 | ||||

| Hertfordshire Grim's Ditch: 1350m long section between Kiln Road and Chesham Road | 1021204 | SP 93308 09264 | ||||

| Hertfordshire Grim's Ditch: 990m long section between Crawley's Lane and Rossway Lane | 1021205 | SP 95146 09186 | ||||

| Hertfordshire Grim's Ditch: 230m long section in Hamberlins Wood | 1021206 | SP 95815 08859 | ||||

| Hertfordshire Grim's Ditch: 210m long section immediately north west of Woodcock Hill | 1021207 | SP 97238 08140 | ||||

| Verulamium, part of wall and ditch of Roman city | 1003519 | TL 13573 06573 | ||||

| Wheathampstead earthwork incorporating Devils Dyke and the Slad | 1003521 | TL 18615 13256 | ||||

| Devils Ditch | 1003522 | TL 12032 08287 | ||||

| Mile ditches | 1003552 | TL 33315 40167 | ||||

| Sections of Grims Ditch | 1005258 | TL 01143 09080 | ||||

| Linear earthwork in Perry's Grove | 1005512 | TL 25849 17001 | ||||

| Mile Ditches | 1006787 | TL 33212 40329 | ||||

| Gannock Grove moated site and hollow-way | 1010907 | TL 36712 35464 | ||||

| Iron Age territorial boundary known as Beech Bottom Dyke | 1019136 | TL 14793 08781 | ||||

| Berkhamsted Common Romano-British villa, dyke and temple | 1020914 | TL 00270 09602 |

Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

Indeed, the modern term “dyke” or “dijk” can be traced back to its Dutch origins. As early as the 12th century, the construction of Dykes in the Netherlands was a well-established practice. One remarkable example of their ingenuity is the Westfriese Omringdijk, stretching an impressive 126 kilometres (78 miles), completed by 1250. This Dyke was formed by connecting existing older ‘dykes’, showcasing the Dutch mastery in managing their aquatic landscape.

The Roman chronicler Tacitus even provides an intriguing historical account of the Batavi, a rebellious people who employed a unique defence strategy during the year AD 70. They punctured the Dykes daringly, deliberately flooding their land to thwart their enemies and secure their retreat. This historical incident highlights the vital role Dykes played in the region’s warfare and water management.

Originally, the word “dijk” encompassed both the trench and the bank, signifying a comprehensive understanding of the Dyke’s dual nature – as both a protective barrier and a channel for water control. This multifaceted concept reflects the profound connection between the Dutch people and their battle against the ever-shifting waters that sought to reclaim their land.

The term “dyke” evolved as time passed, and its usage spread beyond the Dutch borders. Today, it represents not only a symbol of the Netherlands’ engineering prowess but also a universal symbol of human determination in the face of the relentless forces of nature. The legacy of these ancient Dykes lives on, a testament to the resilience and innovation of those who shaped the landscape to withstand the unyielding currents of time.

Upon studying archaeology, whether at university or examining detailed ordinance survey maps, one cannot help but encounter peculiar earthworks scattered across the British hillsides. Astonishingly, these enigmatic features often lack a rational explanation for their presence and purpose. Strangely enough, these features are frequently disregarded in academic circles, brushed aside, or provided with flimsy excuses for their existence. The truth is, these earthworks defy comprehension unless we consider overlooked factors at play.

One curious observation revolves around the term “Dyke,” inherently linked to water. It seems rather peculiar to apply such a word to an earthwork atop a hill unless an ancestral history has imparted its actual function through the ages. Let us consider the celebrated “Offa’s Dyke,” renowned for its massive linear structure, meandering along some of the present boundaries between England and Wales. This impressive feat stands as a testament to the past, seemingly demarcating the realms of the Anglian kingdom of Mercia and the Welsh kingdom of Powys during the 8th century.

However, delving further into the evidence and historical accounts challenges this seemingly straightforward explanation. Roman historian Eutropius, in his work “Historiae Romanae Breviarium”, penned around 369 AD, mentions a grand undertaking by Septimius Severus, the Roman Emperor, from 193 AD to 211 AD. In his pursuit of fortifying the conquered British provinces, Severus constructed a formidable wall stretching 133 miles from coast to coast.

Yet, intriguingly, none of the known Roman defences match this precise length. Hadrian’s Wall, renowned for its defensive prowess, spans a mere 70 miles. Could Eutropius have referred to Offa’s Dyke, which bears remarkable similarity to the Roman practice of initially erecting banks and ditches for defence?

For more information click HERE

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.