Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

Prehistoric Britain saw complex and evolving burial practices, starting with the excarnation of bodies. Dolmens, characterised by their capstones balanced on upright stones, were used as platforms to expose bodies to birds, and wooden palisades encircled the platform, preventing terrestrial animals and rodents from scavenging. (Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain)

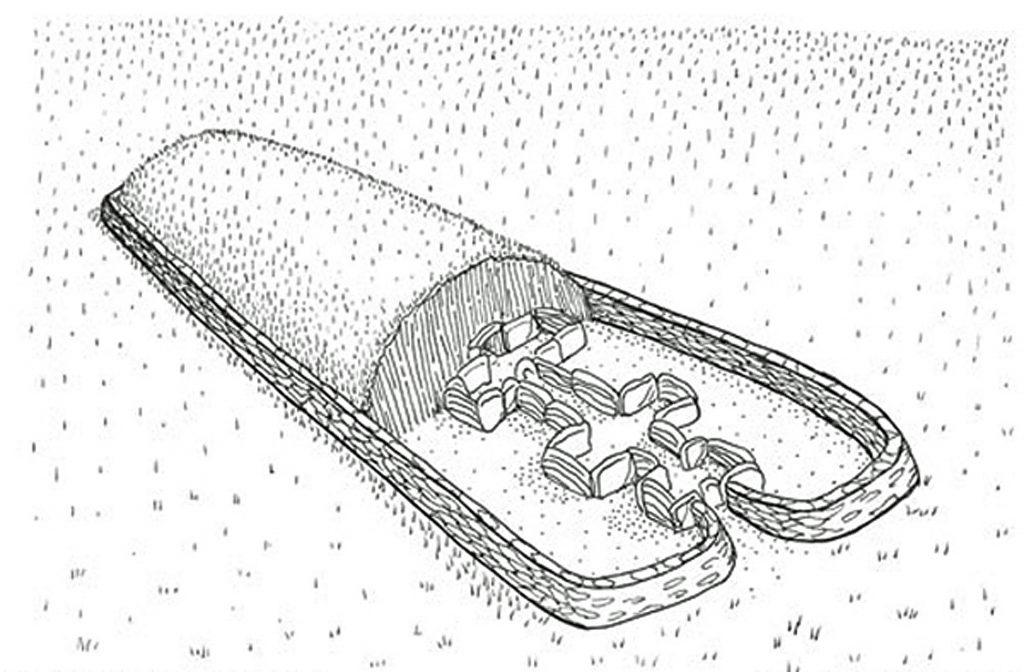

Once cleaned, the bones were collected and stored in long barrow chambers. These megalithic structures were deliberately shaped like boats, symbolising the voyage to the afterlife. The practice dates back to the seventh millennium BCE in France and highlights the cultural significance of these monuments. The misdating of British sites often results from the continuous use of these burial grounds. Older bones were naturally replaced by newer ones, similar to modern graveyards. This ongoing usage has led to confusion, especially when interpreting the age of these sites.

Cremation was another ancient practice, but it began many thousands of years after the first excarnations, indicating a change of culture; this adds further complexity to prehistoric burials. Archaeologists sometimes misinterpret cremated remains at sites like Stonehenge, assuming they date back to the monument’s original use. However, these remains often belong to later periods when ancient sites were reused for other purposes. At Stonehenge, cremated bones have been used to date the site, not recognising that the stones were possibly moved or their sockets were repurposed as burial sites. This misunderstanding challenges the interpretation of the site’s original function.

Round barrows present another puzzle. Often, cremated bones are found on the edges, not in the centre, indicating they were not initially constructed for burials but were later utilised for this purpose. This secondary use complicates the understanding of their primary function.

In areas of Britain like Wales and Ireland, misconceptions about the original function of megalithic sites and their reuse over time have led to confusion among archaeologists. These regions have developed unique site names not found elsewhere, and the designs often reflect changes from excarnation practices to later cremation uses. This has further complicated the understanding of these sites’ function. The intricate design and usage of these megalithic structures underscore the sophisticated burial practices of prehistoric communities. They revered their ancestors and treated death as a significant transition, deserving elaborate and respectful processes.

These burial practices reflect a deep connection with the environment. The boat-shaped long barrows built halfway down the tops of hills symbolised the journey to the afterlife. They were also used as markers for boats on rivers, illustrating the importance of water and travel in their cosmology. Modern archaeological techniques continue to unravel these complexities, revealing a dynamic and continuous use of sacred sites over millennia. Each discovery adds a piece to the puzzle of our ancestors’ beliefs and practices.

In addition to dolmens and long barrows, other megalithic structures played a role in prehistoric burial customs. Cairns and burial chambers, often constructed on hilltops, provided another method for interring the dead. The fact that they have whole bodies and not disarticulated bones indicates that this may have been a halfway house between excarnation and cremation. The community aspect of these burial practices is also notable. The construction of large megalithic structures required coordinated effort, indicating a strong social organisation and shared cultural or religious beliefs. This collective effort would have strengthened communal bonds and reinforced social cohesion.

Rituals associated with burial likely included ceremonies to honour the dead, invoking protection or favour from deities or ancestors. These rituals would have comforted the living, offering a sense of continuity and connection with the past. In some burial sites, grave goods, such as pottery, tools, and ornaments, indicate beliefs in an afterlife where such items would be needed. These offerings reflect the values and daily life of the communities, providing archaeologists with insights into their material culture.

In conclusion, the burial practices of prehistoric Britain were multifaceted and evolved. They reflect a deep connection with the environment, intricate rituals, and a continuous respect for the ancestors, providing a fascinating glimpse into the past. The combination of excarnation, long barrow interment, cremation, and communal effort in constructing megalithic structures illustrates a rich and complex cultural heritage. As modern archaeology continues to explore these ancient sites, our understanding of prehistoric beliefs and practices will continue to grow, revealing how these early societies interacted with their world.

search more accessible and to engage directly with the public can help bridge the gap between current archaeological research and public understanding.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

(Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History)

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Blog Post Review - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Statonbury Camp near Bath - an example of West Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Antonine Wall - Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Rivers of the Past were Higher – an Idiot’s Guide - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Extreme Weather and Ancient Subterranean Shelters - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Antler Pick Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Farming Hoax - (Einkorn Wheat) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: From the Rhône to Wansdyke: The Case for a Standardised Canal Boat in Prehistoric Britain - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Dyke Construction - Hydrology 101 - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: 13 Things You Didn’t Know About Hillforts — The Real Story Behind Britain’s Ancient Earthworks - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Silbury Avenue - Avebury's First Stone Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon's Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Case Study - River Avon - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Cro-Magnons - An Explainer - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Farming Migration Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Prehistoric Canals - Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Problem with Hadrian's Vallum - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Solved - Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Caerfai Promontory Fort - Archaeological Nonsense - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: First Hillforts, Then Mottes — Now Roman Forts? A Century of Misidentification - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Britain's First Road - Stonehenge Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Stone Transportation Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Troy Debunked - Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeological 'pulp fiction' - has archaeology turned from science? - Prehistoric Britain