Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 1. Silbury Hill – misidentified as a burial mound & 2. Marlborough Mount – Motte and Bailey Castle

- 3 3. Brack Mount – missidentified as a Motte and Baily

- 4 3. The Trump

- 5 4. Cadwgan Hall Mount – Motte and Bailey

- 6 5. Bradfield (Sheffield) – Motte and Bailey

- 7 6. Sibbertoft – Motte and Bailey

- 8 7. Castletump – Motte and Bailey

- 9 8. Bicton – Motte and Bailey

- 10 9. Annesley Castle – Motte and Bailey

- 11 10. Pilsbury Castle – Motte and Bailey Castle

- 12 Further Reading

- 13 Other Blogs

Introduction

Misidentification of objects by archaeologists is an unfortunately frequent occurrence, particularly evident in the study of prehistoric fire beacons. This phenomenon can often be attributed to the curricula of archaeological academic programs, which may not always foster a rigorous scientific attitude. This issue is compounded by the perception that these programs are less demanding than disciplines like physics, chemistry, and biology, which typically require a more robust foundation in logic and mathematics for professional success. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History)

The educational limitations in archaeological curricula are further magnified by a trend to prioritise adherence to established classifications over critical analysis. This approach often leads to misidentifications. For example, when faced with a large earth mound, archaeologists might automatically categorise it as a burial mound or a motte-and-bailey site solely based on standard conclusions from past peer-reviewed publications. This reliance on precedent, often rooted in initial assumptions without comprehensive evidence, perpetuates a cycle of educated guesswork.

As a result, a narrative has evolved over the past seventy years that has become challenging for scientists to penetrate and rectify. These historical misinterpretations include the stereotype of “cavemen” who lived in caves and the notion of hunter-gatherers who roamed all day in furs, hunting live game while women gathered berries and fruit. These ideas later evolved into the image of people living in round mud houses with their animals for warmth. Such portrayals conflict with empirical evidence showing that prehistoric societies constructed more durable and sophisticated structures, such as Stonehenge, numerous hill settlements, stone circles, and linear earthworks, which exhibit a level of architectural longevity surpassing even that of the highly advanced Romans.

The advanced woodworking evidenced in sites like Star Carr, which dates back ten thousand years, along with the sophisticated mortise and tenon joints found in stone structures like Stonehenge, clearly contradicts the traditional ‘hunter-gatherer’ classification. These findings suggest a significant misrepresentation of the technological capabilities and societal structures of prehistoric societies in Britain. Recent advancements in scientific tools, such as LiDAR, have further illuminated these inaccuracies. They reveal that these societies were using boats eight thousand years earlier than previously recognised by conventional archaeological narratives. Moreover, the discovery of over 1,500 linear earthworks across Britain indicates that these prehistoric populations were extensively involved in extracting and trading minerals, showcasing a complex and interconnected society much more advanced than the simple hunter-gatherer model suggests.

The evidence of a boat civilisation, which not only engaged in trade over water but also likely lived on these boats due to insufficient terrestrial dwellings, draws parallels to contemporary practices observed in many Far Eastern countries today. If educational institutions included these facts in the curriculum for archaeologists, it could lead to a significant shift in how archaeological finds are interpreted. For instance, when encountering an earthwork like a bank mound, educated archaeologists might consider the likelihood of it being a fire beacon more seriously. This consideration is supported by the prevalence of such structures, which outnumber traditional interpretations like motte-and-bailey or burial mounds in Britain today. This shift in perspective could enhance the understanding and interpretation of archaeological sites, leading to a more accurate reconstruction of historical societies. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History).

1. Silbury Hill – misidentified as a burial mound & 2. Marlborough Mount – Motte and Bailey Castle

According to EH – “The largest artificial mound in Europe, mysterious Silbury Hill compares in height and volume to the roughly contemporary Egyptian pyramids. Probably completed in around 2400 BC, it apparently contains no burial. Though clearly important in itself, its purpose and significance remain unknown.”

The purpose of Silbury Hill remains a mystery today. Originally, it was believed to be a grand burial mound for a mythical King Sil of England and his golden horse. This belief led to excavating a large, dangerous shaft in the mound in search of treasure—a decision influenced by flawed educational presumptions. When this initial excavation failed to reveal any treasures, another horizontal shaft was driven into the mound instead of reconsidering their hypothesis. This, too, uncovered nothing but chalk. The continued lack of findings underscores a significant disconnect and highlights a substantial gap in understanding the historical context and the civilisation that built Silbury Hill.

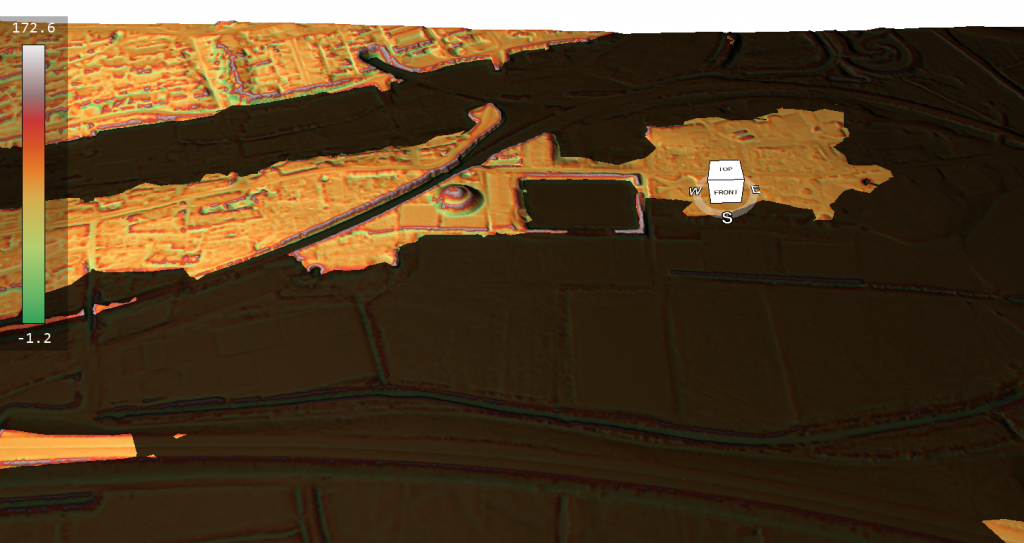

The initial assumption that Silbury Hill was a burial mound led to multiple excavations that failed to uncover any evidence to support this theory. Meanwhile, empirical evidence suggests a different story: during winter, the surrounding area floods, and historical-geographical maps indicate that the River Kennet, nearby, was much larger in the past. Given these facts, it would be reasonable to hypothesise that Silbury Hill served a practical purpose, such as acting as a fire beacon for the boats of the prehistoric society that constructed the mound.

This perspective aligns with the environmental context and the strategic importance of elevated structures in ancient water-based societies. Yet, the reluctance to move away from traditional burial mound theories may reflect a broader hesitation within the archaeological field to embrace new interpretations without definitive archaeological evidence, leaving the true purpose of Silbury Hill still largely a matter of conjecture in the eyes of archaeologists.

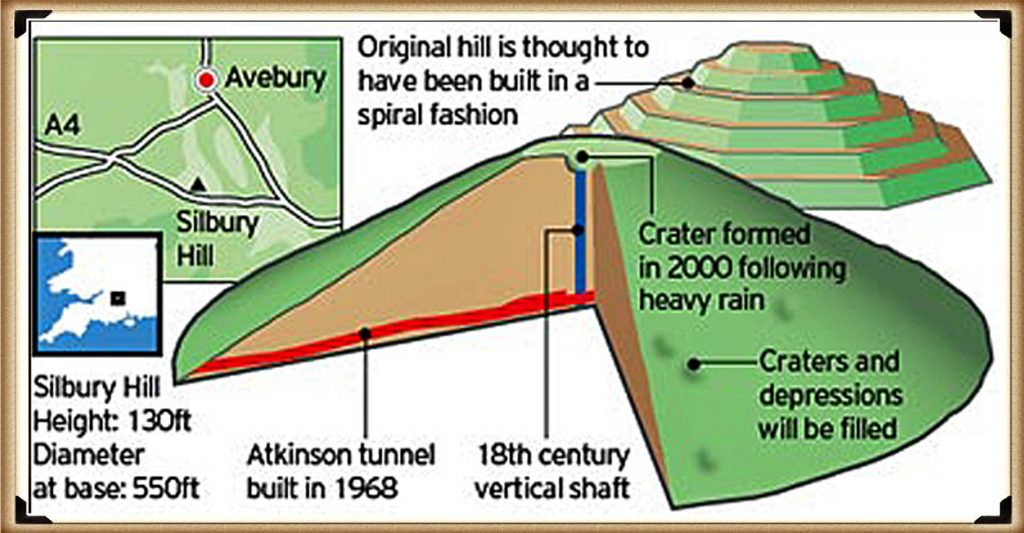

If you understand how the landscape looked and was used in the past, then such beacons can be easily found all over Britain, even ones built, to a similar design to Silbury hill To find this unique design we can look at the most recent re-excavation and detailed examination of Silbury Hill, by English Heritage. For only a few years ago it needed to be ‘shored up’ because of the reckless archaeologists of the past, cutting vast tunnels and shafts into the hill, looking for tombs and treasure making it totally unstable. This investigation showed for the first time that the hill was built like the pyramids of Egypt and South America in steps. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History).

This is from The Daily Mail in 2010:

| Figure 78 – Silbury Hill made like a ‘layer cake’ – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

Silbury Hill – one of the most mysterious and striking monuments in Britain – was a prehistoric ‘cathedral’, built layer by layer over 100 years, a new study suggests. The 4,000 year-old earth mound, which towers over the Wiltshire countryside, was the tallest human-made structure in Europe until the Middle Ages.

However, despite its size, and repeated attempts to tunnel into the heart of the mound, archaeologists have long been puzzled about how and why it was created.

Now a new book published by English Heritage suggests that the 120 ft high hill was not built to a grand blueprint but was assembled by at least three generations of Bronze Age Britons between 2400 and 2300 BC. A study of soil, rocks, gravel and tools inside the hill shows that it went through 15 distinct stages of development.

Dr Jim Leary, English Heritage archaeologist, said the creators were building the mound as part of a ‘continuous storytelling ritual’ – and that the final shape of the mound may have been unimportant. He argues that the familiar outline of stepped sides and the flat top visible today is primarily the result of Anglo-Saxons and later alterations.

“Most interpretations of Silbury Hill have, up to now, concentrated on its monumental size and its final shape,’ he said. ‘It has generally been thought to be a concerted effort of generations of people building something out of a common vision and spiritual zeal akin to that spurred the creation of soaring medieval cathedrals.

‘The flat top, especially, was often seen to be a “platform” deliberately built to bring people closer to the skies. ‘But new evidence is increasing telling us that our Neolithic ancestors display an almost obsessive desire to constantly change the monument – to rearrange, tweak and adjust it. It’s as if the final form of the Hill did not matter – it was the construction process that was important.”

Silbury Hill lies close to the stone circles of Avebury and a few miles from Stonehenge. Archaeologists estimate that it would have taken 700 men working for ten years to build out of soil and chalk. It started as a low gravel mound before it was transformed into a pile of soil and rock surrounded by a ditch.

Dr Leary added: “The most intriguing discovery is the repeated occurrence of antler picks, gravel, chalk and stones in different kinds of layering, in ways that suggest that these materials and their different combinations had symbolic meanings. We don’t know what myths they were representing but they must have meant something quite compelling and personal.

What we do know is that by the time work on the hill had started in the later Neolithic period, the surrounding area was already saturated with evidence of past use; it was a place that was heavily inscribed with folk memories that recalled ancestors and their origins. What is emerging is a picture of Neolithic people having the same need to anchor and share ideas and stories as we do now, and that built structures like Silbury Hill may not be conceived as grand monuments of worship but intimate gestures of communication.”

The hill was damaged in the 18th century when archaeologists sank a vertical shaft from the top. In the 1840s, a tunnel was dug into the mound from the edge, while in 1968 BBC2 filmed a new attempt to tunnel into the centre of the mound.

After parts of the mound began to sink in 2002, English Heritage reopened the BBC tunnel, took samples of soil and rock, filled in the gaps and sealed the mound for good.

Dr Leary now believes the mound went through 15 stages of construction – and up to 100 different phases within four or five generations. It would make sense that a monument was a round-based hill made in layers (similar to Marlborough Mound – sometimes known as Merlin’s Barrow, also excavated by Dr Leary, hence his idea!). The question not answered by archaeologists is – why build this monument in stages?

Fortunately, the answer is simple – to make it higher, for Silbury was a beacon to attract ships to its harbour. Over time the height of the mound was raised to increase the beacon’s visibility. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History).

| Figure 79 – Marlborough Mount – Built like Silbury Hill – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

‘The flat top, especially, was often seen to be a “platform” deliberately built to bring people closer to the skies.

Unfortunately, the article is also full of nonsense like this quotation. So, the ancestors built a hill at the bottom of a valley to get closer to the skies – is it me, or can anyone see the error in this statement? You may therefore respond to my criticism by asking – wouldn’t a beacon on top of a hill have greater visibility? Yet the reason the beacon is located in the watery harbour and not on top of a hill is that the light shows the exact location of mooring places, in bad weather and at night, when visibility is poor.

This type of device can be seen throughout our recent nautical history as illustrated at the Spurn Point Lighthouse. The earliest reference to a lighthouse on Spurn Point is 1427, which was a coal-fired lighthouse at the ground level. There were several lighthouses of various designs until in 1767; John Smeaton was commissioned to build a new pair of lighthouses (one a 90ft tower). The 1895 lighthouse is a round brick tower, 128ft tall, painted black and white. It was designed by Thomas Matthews. Its main light had a range of 17 nautical miles.

Silbury Hill also started at ground level and was built up (like Spurn Point) over hundreds of years until it reached the 120ft height seen today. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History).

From the Guardian 31st May 2011

For generations, it has been scrambled up with pride by students at Marlborough College. But the mysterious, pudding-shaped mound in the grounds of the Wiltshire public school now looks set to gain far wider acclaim as scientists have revealed it is a prehistoric monument of international importance.

After thorough excavations, the Marlborough mound is now thought to be around 4,400 years old, making it roughly contemporary with the nearby, and far more renowned, Silbury Hill.

The new evidence was described by one archaeologist, an expert on ancient ritual sites in the area, as “an astonishing discovery”. Both Neolithic structures are likely to have been constructed over many generations.

The Marlborough mound had been thought to date back to Norman times. It was believed to be the base of a castle built 50 years after the Norman invasion and later landscaped as a 17th-century garden feature. But it has now been dated to around 2400BC from four samples of charcoal taken from the core of the 19-metre-high hill.

The Marlborough mound has been called “Silbury’s little sister”, after the more famous artificial hill on the outskirts of Avebury, which is the largest manmade prehistoric hill in Europe.

Marlborough, at two-thirds the height of Silbury, now becomes the second largest prehistoric mound in Britain; it may yet be confirmed as the second largest in Europe.

Jim Leary, the English Heritage archaeologist who led a recent excavation of Silbury, said: “This is an astonishing discovery. The Marlborough mound has been one of the biggest mysteries in the Wessex landscape. For centuries, people have wondered whether it is Silbury’s little sister, and now we have an answer. This is a very exciting time for British prehistory.”

(Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History)

Fire Beacon

Marlborough Mound shows that fires were light on the hill throughout its use, and the same fact can be found at Silbury Hill. Jim Leary’s excavations showed signs of fire and associated dates for these charcoal remains. According to jim:

Old Land Surface

Sample: OxA-20808

Hazelnut fragments (from the same hazelnut) from [4041] – sample <9821>, sub sample of <9435>. [4041] is a concentration of charcoal comprising charred hazel nutshell fragments and other charred remains as well as two pig or wild boar teeth. It was recorded within a small, defined area of the upper part of the OLS (4041]) on the north side of the East Lateral in Bay 7, and is thought to indicate the remains of a hearth.

Radiocarbon Date: 4012±29; 2620–2460 cal BC; 2510–2465 cal BC

Sample: SUERC- 24089

Maloideae branchwood (single entity) as OxA-20808

Radiocarbon Date: 4030±35; 2840–2470 cal BC; 2510–2465 cal BC

This presence of charcoal is reinforced by: Canti, Matthew & Campbell, Gill & Robinson, D.. (2004). Site Formation, Preservation and Remedial Measures at Silbury Hill. Who reported that: ” The remaining part of Core 5 consisted of around 29 m of chalk rubble from the rest of the mound, and this was also assessed for the presence of biological remains. Samples were taken at 25 cm intervals respecting interfaces, and floated using a 0.25 mm mesh for the flot and a 0.5 mm mesh for the residue. Tiny fragments of charcoal were present at intervals throughout the depth of the mound.”

This clearly shows that both Fire beacons were used around 2400 – 2500 BCE, when the Neolithic Waters were still high and could carry boats. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History).

3. Brack Mount – missidentified as a Motte and Baily

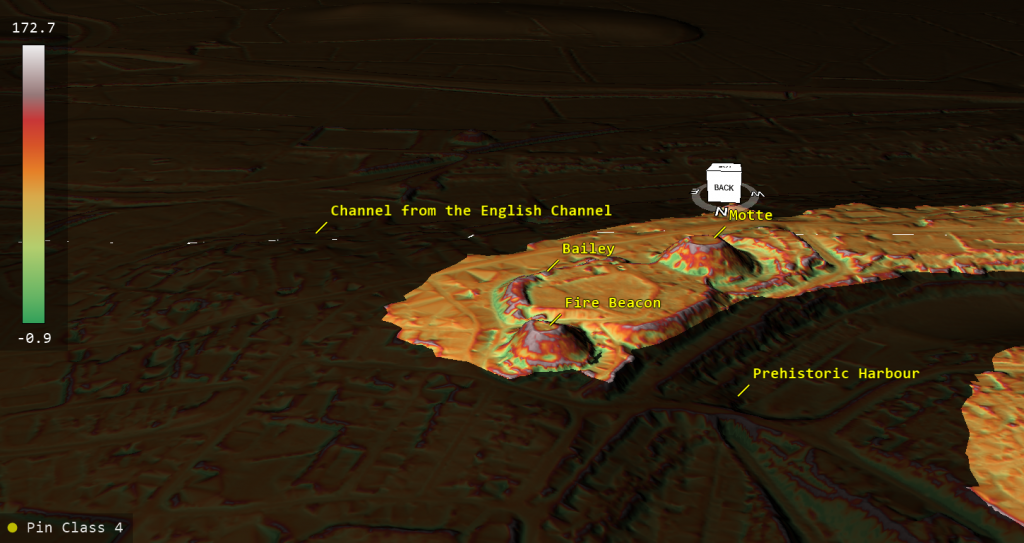

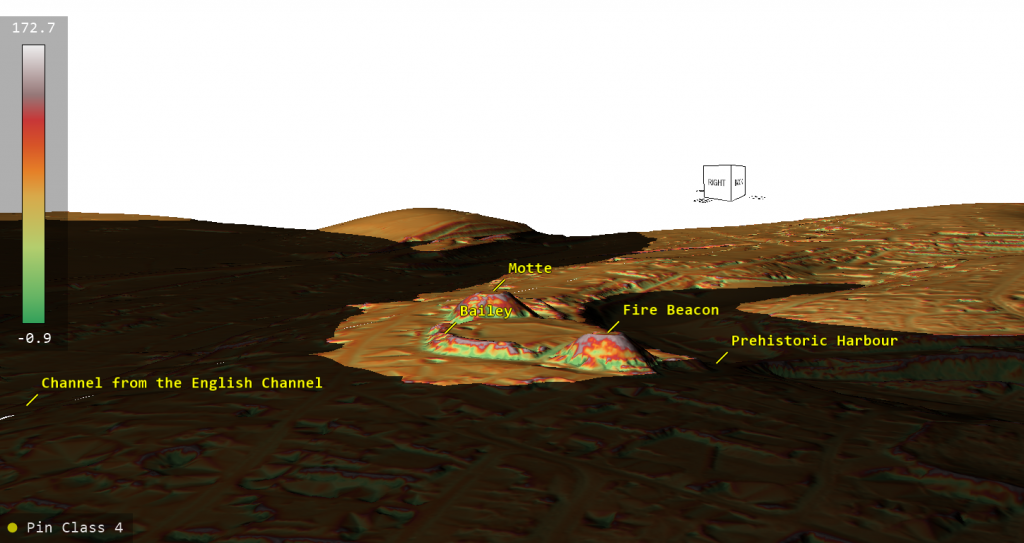

In Lewes, a village nestled in the South Downs, stands an intriguing prehistoric structure known as the ‘Brack Mount’. Local historians have traditionally linked this mound to the nearby Norman Castle, presenting it as an additional feature connected by a wall to the main Motte and Bailey structure. This interpretation paints the Brack Mount as an integral part of the medieval landscape, purportedly serving to attract shipping.

However, recent archaeological investigations complicate this picture. A Norman well was discovered at the summit of the Brack Mount. This finding raises significant questions about the dating and function of the mound. The construction of a 50-foot high earth mound followed by the excavation of a 60-foot deep well at its peak suggests a sequence of use that might not align with the timeline of Norman castle construction. Why would you attempt to build a well in a mound that you have constucted and so know it will not contain water until it reaches ground level?? This discrepancy implies that the Brack Mount could predate the Norman structures, possibly serving an entirely different function before being adapted for use by the Normans.

This mount existing at an earlier date has now been accepted by arachaeologists especially as Roman finds have been found in test pits on the mount:

“While the form of the mound which survives to this day is undoubtedly Norman in date, it has recently been suggested that it may have utilised the site of one of a number a pre-existing tumuli or burial mounds of possible Romano-British origin located within the bounds of the later settlement (Bleach 1997). A factor underpinning the site’s potential ritual and later strategic use was its dominant position within the landscape for it marks the end of a prominent chalk spur ommanding excellent views of the Ouse Valley, especially upstream.” Lewes archeological society.

The presence of the well might indicate that the mound was originally built with a different purpose in mind, perhaps even as a beacon or lookout point, which was later repurposed to serve the castle. This theory challenges the traditional interpretation and suggests a more complex historical usage of the landscape in Lewes. If we look at the LiDAR map of Lewes we can see how the Town once was not only on a great river but was a harbour for boats from the English Channel.(Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History).

3. The Trump

The Lewes Trump, another significant mound often dismissed by archaeologists as merely a garden feature, raises further questions about the historical landscape of Lewes. Standing at 75 feet high with a circumference of 140 feet, its dimensions suggest a purpose far more substantial than ornamental garden decor. Located on the edge of the monastery’s grounds, this mound, originally known as The Mount, is strategically placed on Lewes’s prehistoric shoreline, according to LiDAR maps.

Adjacent to The Trump is an ancient site known as the “dripping pan,” historically used by Cluny Monks for salt production, a process that required constant access to saltwater. This proximity to a salt production site and its strategic positioning on the former shoreline lend credence to the argument that The Trump served a navigational purpose. It likely functioned as a fire beacon, guiding ships—particularly those from France through the English Channel—towards safe harbours and the monastery.

These insights challenge the more straightforward interpretation of The Trump as a garden feature, instead highlighting its role in a complex network of maritime navigation and monastic industry, underscoring the need to reevaluate such historical structures beyond their immediate physical context. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History)

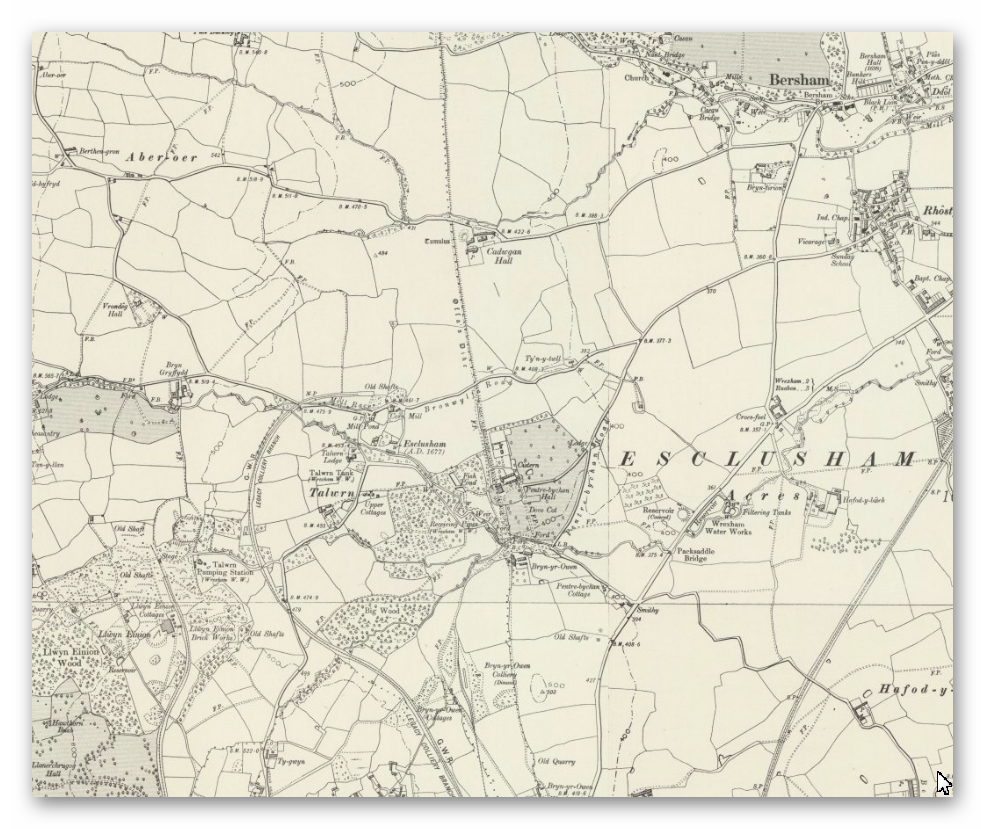

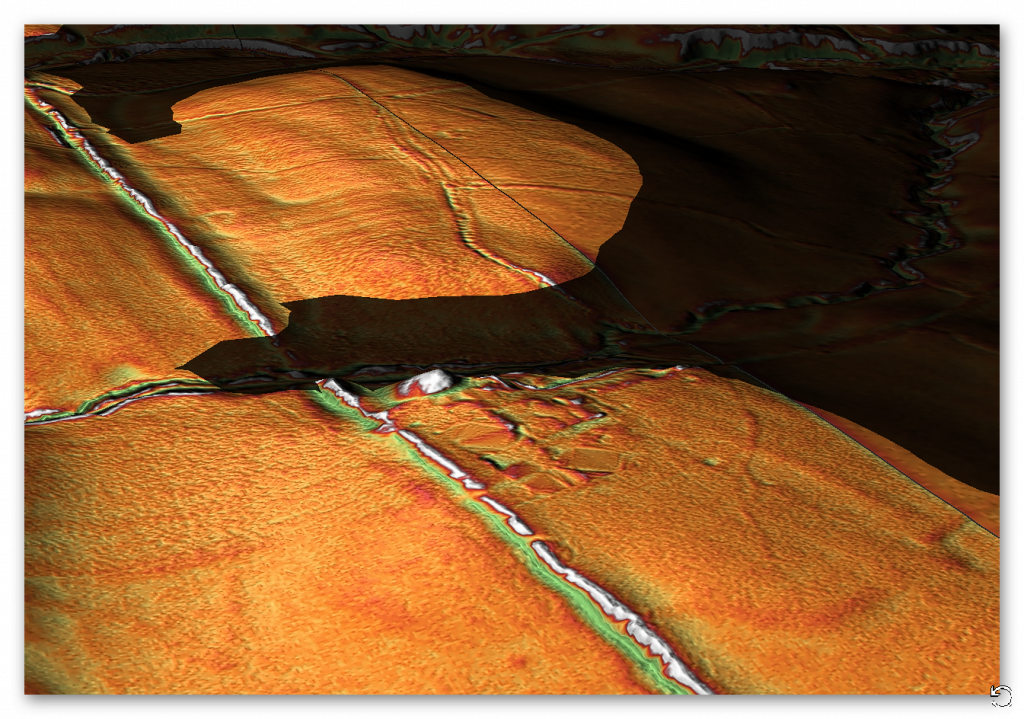

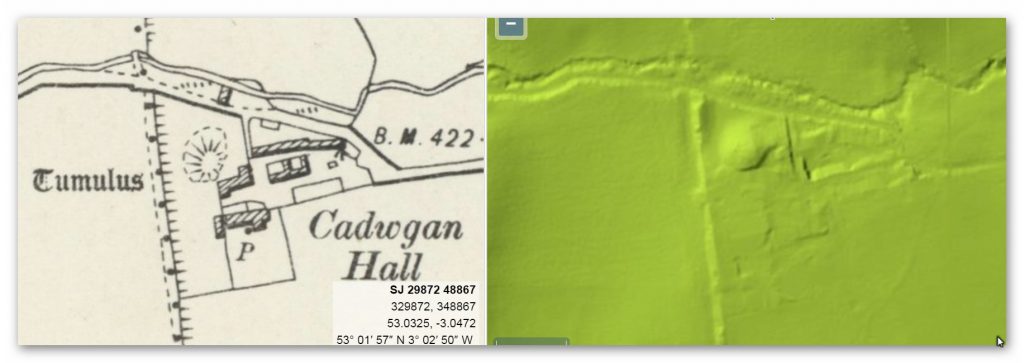

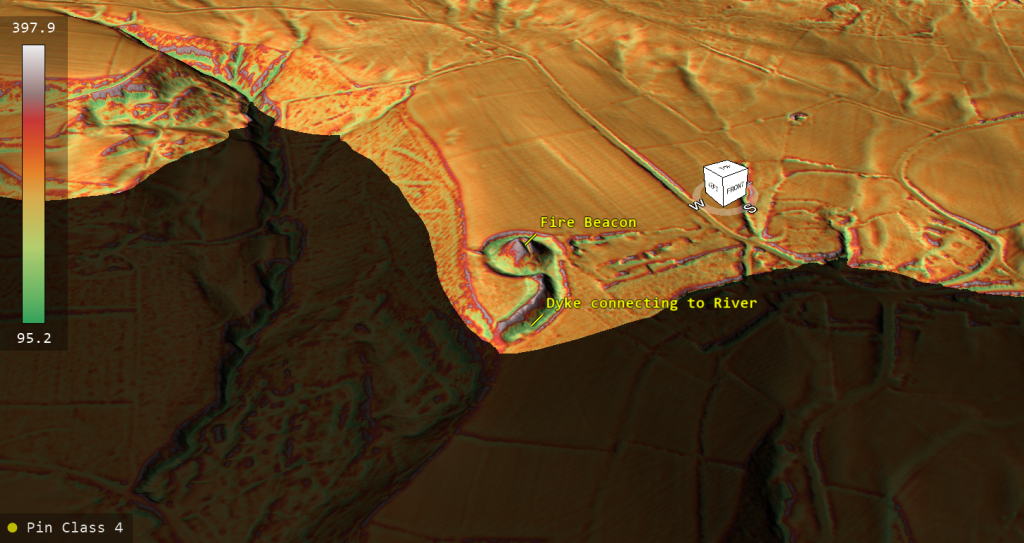

4. Cadwgan Hall Mount – Motte and Bailey

Plas Cadwgan mound is a mutilated oval hillock used for livestock in a field next to the farm of the same name. It is immediately next to Offa’s Dyke, and part of it was cut away to create an air raid shelter in the Second World War. There is some debate about whether it was actually a motte or not, but strategically it matches others of this type next to a crossing point and stream. There is no evidence of a bailey but there is the suggestion of a ditch, and that it was used as a burial mound in antiquity.

LiDAR clearly shows that this is a mound on a river – that would have been much larger in the past and there can only be identified as a ‘Fire Beacon’ for boats.

(Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History)

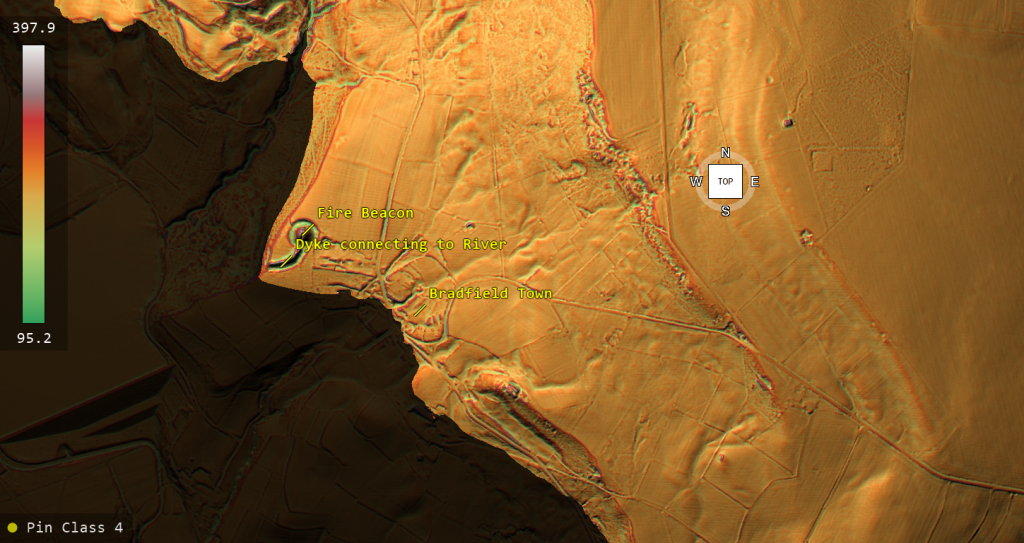

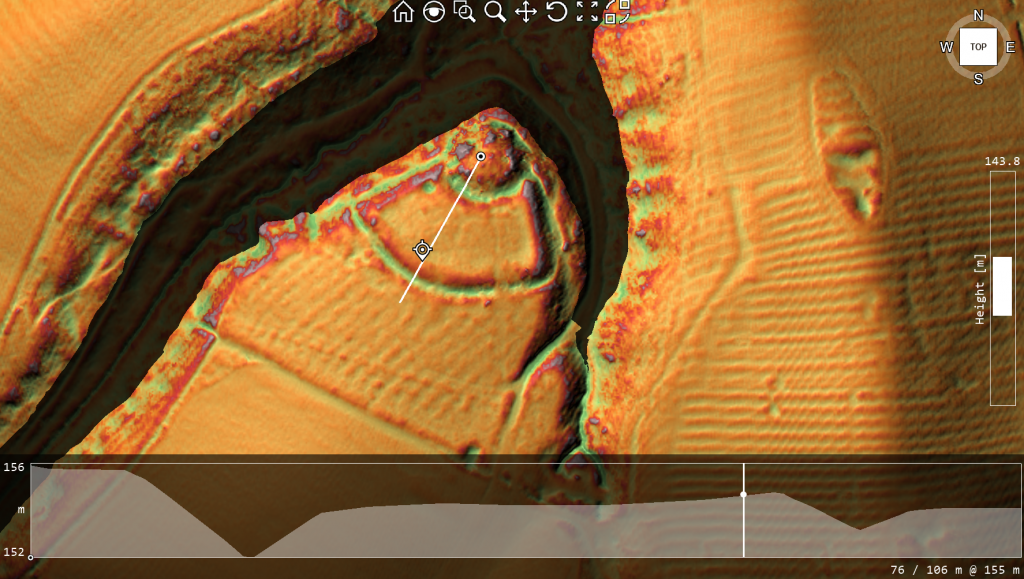

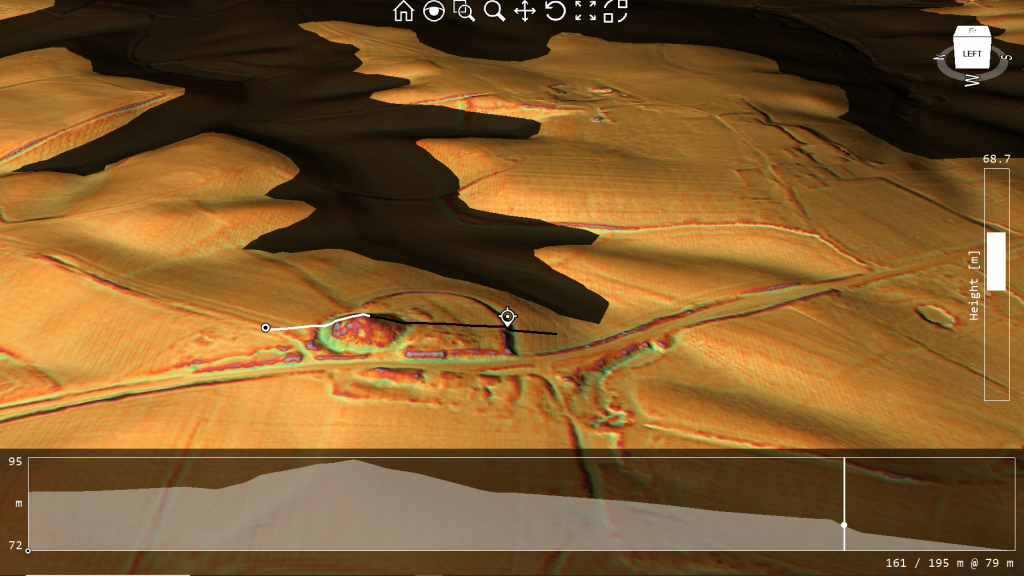

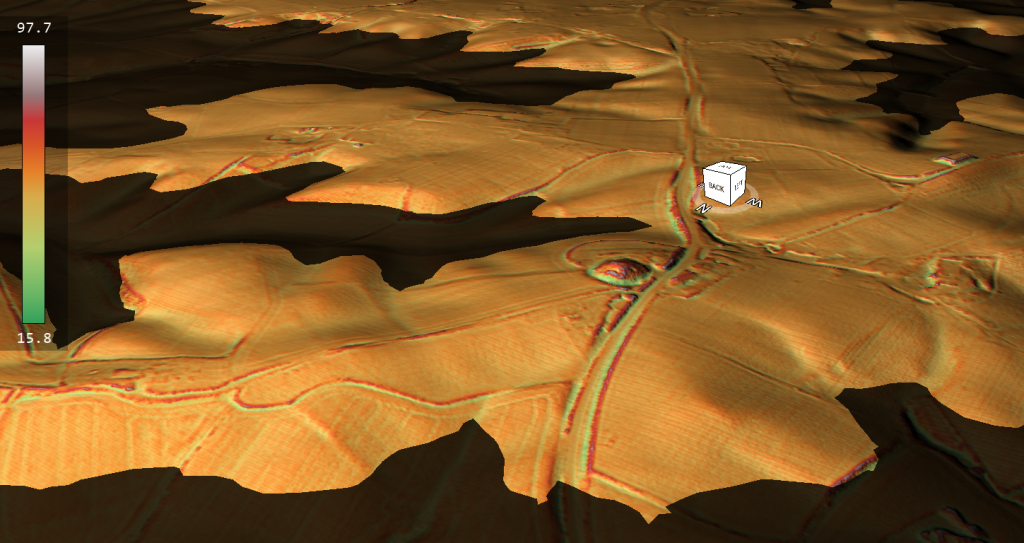

5. Bradfield (Sheffield) – Motte and Bailey

According to HE – “Believed to be a 12th century castle of the de Furnivals, the monument comprises a motte c.18m high whose summit has been disturbed by amateur excavation, leaving it crescent shaped in plan. During excavations in 1720, squared tool-marked stones were found which have been interpreted as the foundations of a tower. A deep, steep-sided ditch c.9m wide circles the motte to the north and extends southward along the east flank of the monument, following the south-westward curve of a substantial 8m wide rampart. At its northern end, the rampart stops just short of the motte. At its southern end, it curves round to meet the edge of the sharp drop down into the valley of Rocher End Brook. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History) This scarp forms a natural western defence to a small semi- circular bailey measuring c.15m x 30m, though it is likely this edge was also palisaded. A low bank running between the scarp and the motte ditch at the northern end of the bailey is all that survives of another section of rampart. A causeway across the motte ditch just south of this was a point of access to the motte from the bailey. Access to the bailey seems to have been from the south-west or, alternatively, from the east across the outer ditch, where a route up from the village and church would have passed through the gap between motte and rampart. A ditch also divides the bailey from the east rampart. Modern walling and fencing is excluded from the scheduling though the ground beneath is included.“

The case of Bradfield offers an intriguing puzzle in historical interpretation and archaeological classification. According to the Domesday Book, Bradfield didn’t exist during the Norman period, which raises significant questions about the motivations behind constructing an expensive Motte and Bailey there. Without a local population to tax, the financial rationale for maintaining an expensive garrison becomes unclear—especially without the traditional threats from the Welsh or Picts to justify such fortifications.

Furthermore, the defensive Bailey at Bradfield is notably small, measuring just 15 meters by 30 meters, which further complicates understanding its purpose. Such a diminutive size seems impractical for significant defensive operations, challenging the notion that it was built with a primary military purpose in mind.

This scenario illustrates a broader issue within archaeology: the tendency to assign a “Motte and Bailey” classification to any unidentifiable mound. This default categorisation can lead to misinterpretations of archaeological sites, as it may oversimplify or entirely overlook the actual historical and functional complexities of these structures. In the case of Bradfield, the lack of contemporaneous settlement and the impractical size of the Bailey suggest that alternative explanations for the mound’s purpose should be explored, rather than settling for a conventional but possibly inaccurate historical narrative. Such instances highlight the need for more nuanced archaeological methods and interpretations that consider all available evidence and context.

The reason for all this prehistoric activity (and probably some Roman – so it could be a Roman Beacon?) is the vast quarry site in this region and the use of the Dyke to send minerals out for processing and trading.

6. Sibbertoft – Motte and Bailey

According to EH – “The motte and bailey castle at Sibbertoft, known as Castle Yard, is situated 800m to the south of Marston Lodge farm and south of the dense woodland of Marston and Sibbertoft woods. Sibbertoft motte and bailey is located on the north spur of a natural hilltop, and the round flat topped mound of the motte stands approximately 3m above this hill. On its southern side the motte is bounded by a ditch 2.5m deep and 6m wide and on the northern side there is narrow ledge with a slight outer bank about 0.25m high. Within the area of the top of the motte slight depressions indicate the location of former buildings. The bailey lies to the south and south east of the motte and covers an area about 100m x 50m. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History) A ditch 1m deep surrounds the bailey on the southern side and there is a slight inner bank 0.5m high on the south, west and east sides of the bailey. This motte and bailey is considered to have been constructed in the late 11th century or early 12th century. Outbuildings on the site are excluded from the scheduling, but the ground beneath is included”.

Sibbertoft presents another example where traditional archaeological classifications may not fully align with the historical and geographical realities. The classification of Sibbertoft as a ‘Motte and Bailey’ raises questions due to several unconvincing features of the site. The motte is relatively insubstantial, rising only 2 to 3 meters above the surface, which is unusually low for a structure that was intended to be defensively formidable. Additionally, the associated bailey is characterized by a very shallow outer ditch, merely 1 meter deep, which further diminishes its credibility as an effective defensive structure.

Furthermore, the motte’s strategic positioning does not offer a commanding view over the town, which, according to the Domesday Book, comprised only 18 households during the period in question. This small population base would have made the construction of a traditional Motte and Bailey an economically unjustifiable venture, considering the expense involved in building and maintaining such a fortification without adequate economic returns.

Given these factors, it is plausible to consider that Sibbertoft’s mound may originally have served a different purpose—potentially as a fire beacon. This would align with using elevated structures as navigational or signal points. It is conceivable that the site was later repurposed as a defensive position, perhaps in response to changing political or military needs, even if it was not ideally suited for this role. This hypothesis encourages a reevaluation of Sibbertoft and similar sites, suggesting that a flexible understanding of their historical uses may provide a more accurate interpretation of their origins and functions.

7. Castletump – Motte and Bailey

According to HE – “The monument includes a motte and bailey castle situated on high ground, known as Castle Tump. The castle was granted temporarily to William de Braose between 1148 and 1154 by Roger, Earl of Hereford. The motte was considered to be a meeting place for Botloes Hundred. The visible remains include the large mound of the motte, with the flattened area of the bailey surrounding it and extending to the south. The motte stands to about 14m, and has a flattened top about 8m in diameter. There are no signs of any structures on top of the mound, although these will survive as buried features. About 6m from the base of the motte on its north side is a bank generally about 1m high, but rising to 2m high in places, which now forms a field boundary. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History) This was the boundary of the bailey on this side. The bailey follows the field boundary around to the south shelving off sharply beyond this. On the south side the change in levels between the bailey and the land outside is about 2.5m, and the bailey appears to have been terraced. It is reported that a double bank on the line of the bailey was removed in 1946-47. About 5m from the base of the motte on its north west side is a pond 15m long, 3m wide and about 0.7m deep, thought to be spring fed, which may be the remains of the moat which would have encircled the motte. A number of features are excluded from the scheduling; these are post and wire fences, the brick wall bounding the property on the west side and the cement and post and wire fence above it, although the ground beneath all these features is included. The house and extensions known as `Castle Tump’ and its surrounding garden and outbuildings are not included in the scheduling.”

The frequent misclassification of historical mounds as Motte and Bailey structures highlights a significant oversight in archaeological interpretation. Many of these mounds are located on the edges of prehistoric waterways rather than near towns or roads that would support the typical Norman use of Motte and Baileys as garrison sites. The Norman model required substantial financial investment for construction and maintenance, which was typically recuperated through local taxation. This economic model necessitates a sizable nearby population to sustain the costs.

However, positioning many mounds in less populated or economically viable areas contradicts this requirement, suggesting that these mounds may not initially have served as Motte and Baileys. Despite this, archaeologists have often defaulted to this classification without considering such an interpretation’s economic and strategic feasibility.

This pattern suggests a need for a more nuanced approach in archaeological classification that considers the broader geographical and economic contexts of these structures. Recognising that not every mound fits the Motte and Bailey category could lead to a more accurate understanding of their historical roles, potentially identifying alternative uses such as lookout points, meeting sites, or fire beacons that align better with their locations and available evidence.

Castle Tump presents yet another instance where traditional archaeological classifications may be misleading. The mound is notably not flat-topped, as would typically be necessary for a Motte, and its width is a mere 8 meters, casting further doubt on its identification as a Motte and Bailey structure—especially given the historical context that suggests no significant population lived here during the Norman period to justify such a defensive construction.

The small size of the outer ditch also implies that the site might have served purposes other than castle defence. This invites speculation about alternative functions for the mound, which might not align with conventional military uses.

Adding to the intrigue is the proximity of a Roman road, suggesting a possible connection to earlier periods. This road is unusual in that it seems to be built on a bank of a linear earthwork or dyke. It is cut into the surface rather than being elevated, as is typical for Roman road construction aimed at ensuring proper drainage. This anomaly could indicate that the road and possibly the mound predate the Roman occupation and were later adapted to Roman infrastructure needs.

The debate around Castle Tump might indeed be expanded to consider the broader historical landscape, including the age and purpose of adjacent features like the Roman road and the linear earthwork. Such an inquiry could provide deeper insights into the regional history and the chronological layering of human activity in the area, moving beyond the Motte and Bailey classification’s limited and sometimes inaccurate framework.

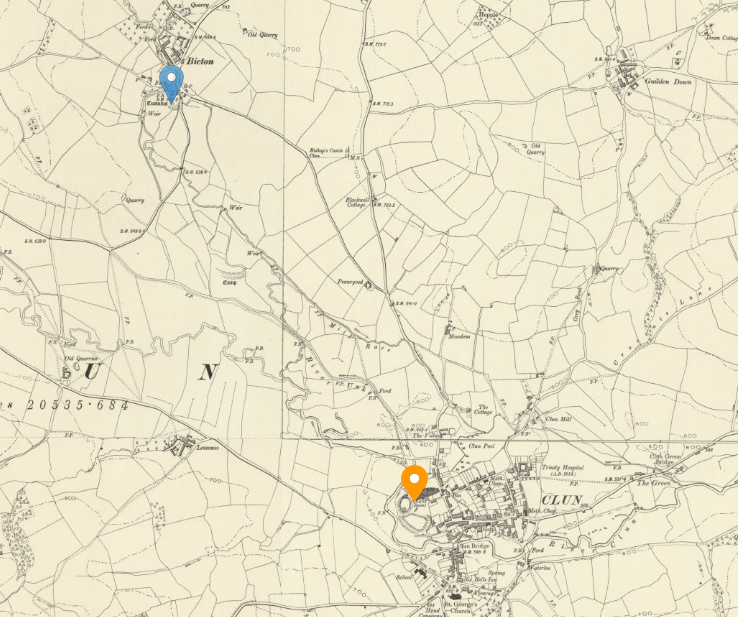

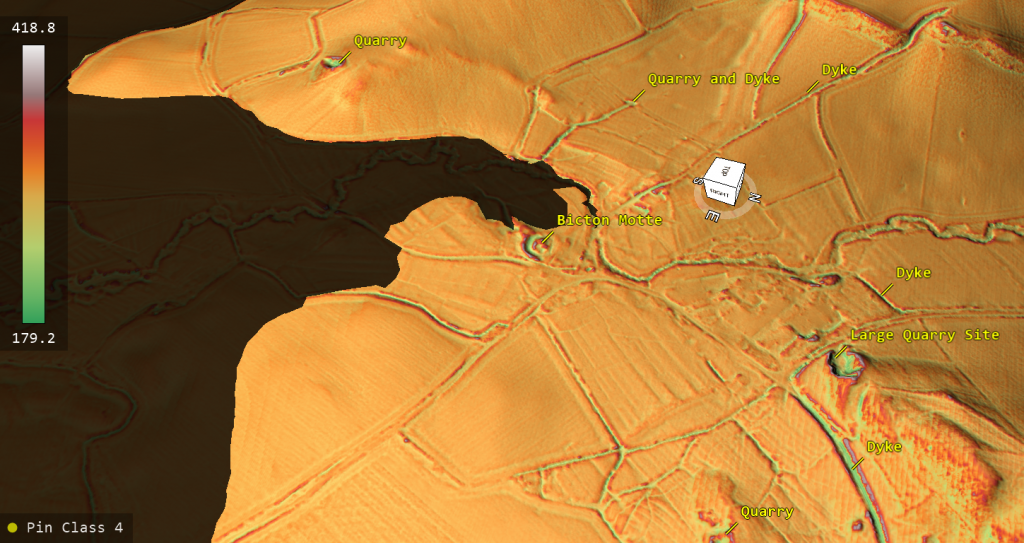

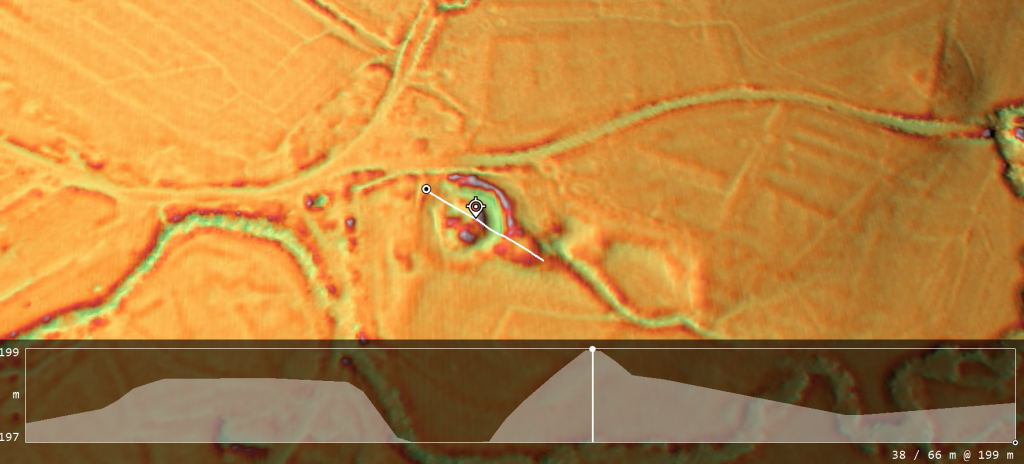

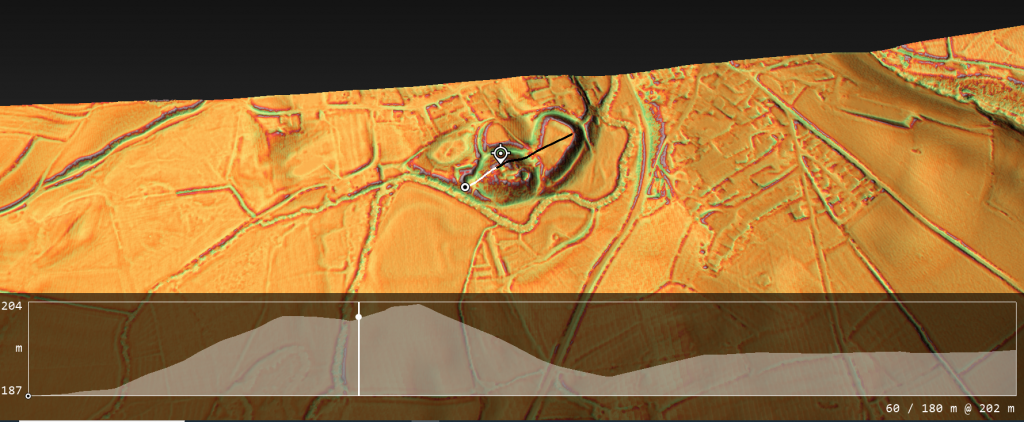

8. Bicton – Motte and Bailey

Accrding to HE – “The monument includes the earthwork and buried remains of a motte and bailey castle to the south of the hamlet of Bicton. It has been constructed by adapting a low elongated glacial mound, on the eastern side of the flood plain of the River Unk. It is situated 1.9km upstream of Clun Castle located next to the River Clun, which is the subject of a separate scheduling. The close proximity of these two castles suggest that they acted together during the early Middle Ages to control river crossing points and the movement of people along the valleys. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History) The oval shaped motte appears to have been originally circular, approximately 30m in diameter at its base. It has been modified by later quarrying for gravel and now stands to a height of 2.2m. A dry flat-bottomed ditch surrounds the motte, which is defined by an external bank and a small bailey to the south. The south eastern part of the bank is about 8m wide and also stands about 2.2m high. The rest of the bank is now visible as a slight earthwork, having been reduced in height by later quarrying and the digging of drainage ditches. The southern part of the glacial mound appears to have been deliberately altered to form a small bailey, a level rectangular platform measuring approximately 14m by 25m. A former field boundary has cut into the base of the scarp which defines the western side of this platform.”

The situation at Bicton Motte highlights another instance where conventional archaeological interpretations may be insufficient or misleading. The proximity of Bicton Motte to the enormous Clun Castle—just 1.2 miles away—raises valid questions about the economic and strategic rationale behind constructing two castles so close together, primarily when they differ significantly in design and size.

This scenario suggests a potential oversight in the economic understanding of such constructions by some archaeologists, who may prioritise fitting finds into existing historical narratives at the expense of exploring alternative explanations. The proximity of these two structures might have allowed for cooperative use in later periods, but this does not explain the initial decision to build both. This is especially relevent as the Doomsday book reports that Bicton had just 6 households in the village.

Furthermore, Bicton Motte’s location on the river shoreline and surrounding landscape, notably marked by extensive quarries, points to a potentially different original purpose. These quarries indicate longstanding human activity predating the Norman invasion, which could suggest that Bicton Motte served as a strategic site for other purposes, such as a fire beacon. This is supported by its geographical position, ideal for signalling and communication and crucial for navigation and trade, especially along waterways.

The presence of quarries also underlines a continuous utilisation of the area, possibly for resource extraction, which would add another layer of practical significance to the site beyond mere military use. This context, combined with the historical usage of fire beacons by prehistoric societies and the Romans, could provide a more comprehensive understanding of Bicton Motte’s historical importance, suggesting that its actual function and significance might have been oversimplified or misunderstood in the framework of medieval fortifications.

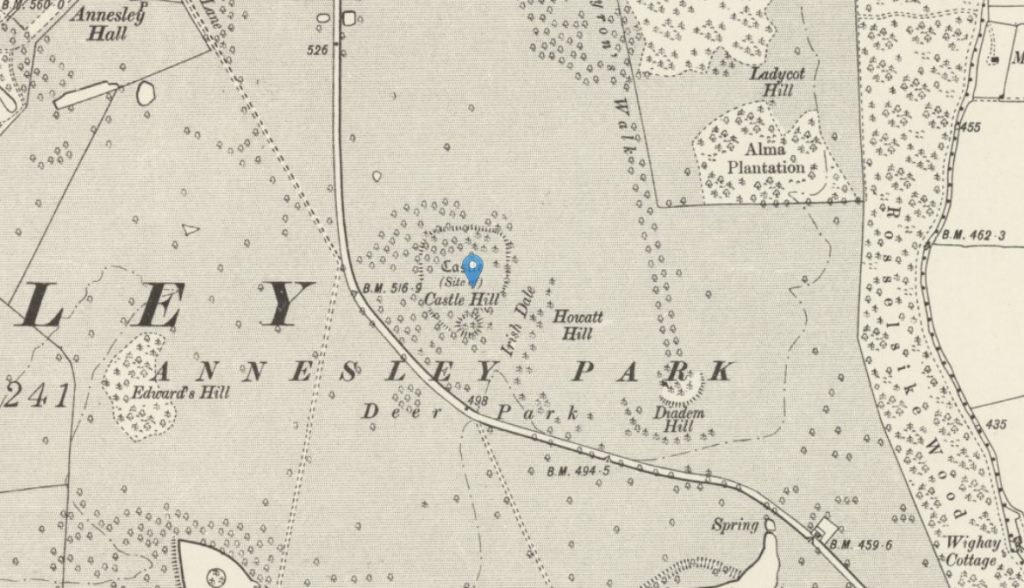

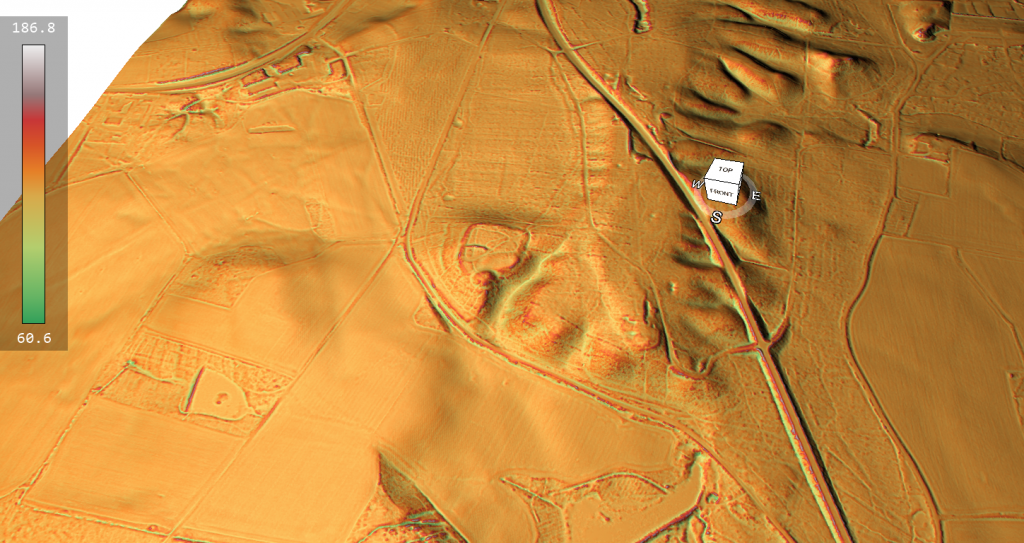

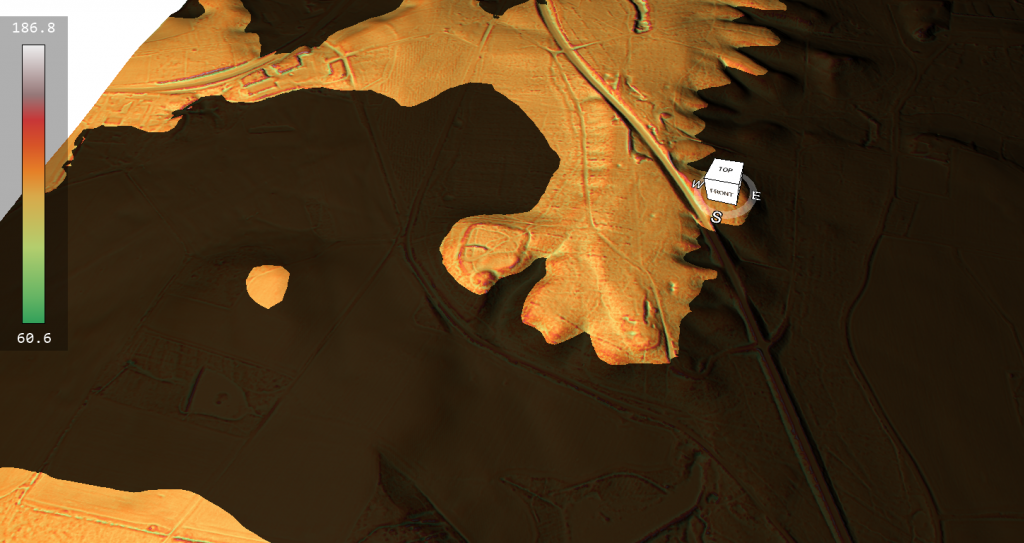

9. Annesley Castle – Motte and Bailey

According to EH – “The monument includes the motte and two baileys of Annesley motte and bailey castle. The motte is on the south side of the monument and built on the edge of a deep gully so that, although from the north it stands only some 3m high, on the south side it drops sharply to the bottom of the gully c.30m below. It is a roughly circular mound with an average diameter of 42m. A palisade would have enclosed the top and wooden buildings would have occupied the interior. At a number of examples of this class of monument, the palisade was replaced by a stone shell keep in the later Middle Ages, but there is as yet no evidence that this occurred at Annesley. On the south side, the motte relied largely on the steep natural slope for defence and is unusual in that there is no trace of a ditch around it. On the north side it was protected by the bailey which comprises a sub-rectangular area measuring c.120m from east to west by c.150m from north to south. There is no trace of a rampart round the edge of the bailey which is instead demarcated by the natural slope and would also have been enclosed by a palisade. Outside the palisade, the slope has been scarped to create a 10m wide berm or terrace which can be traced most clearly on the south-west side and the north-east corner of the monument. The entire enclosure was divided in two so that there were, in effect, two baileys which would have had different functions and would have contained a variety of ancillary features including domestic and garrison buildings and corrals for stock and horses. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History) The line of this division can be traced from the west side of the monument where a 1.5m high bank extends for c.50m and ends approximately midway across the bailey. It is not yet clear whether the fence or wall that surmounted this bank then continued in a straight line to the east side of the bailey or whether it turned at right-angles towards the motte. The latter is more likely because a second bank, roughly parallel with the first and starting on a line with its east end, can be seen running eastward from near the foot of the motte to join the east side of the bailey. Although much lower than the first, this bank is of a similar width, being c.5m wide, and would also have been surmounted by a wall or palisade. This palisade would have connected the two banks across the gap between them, creating a small highly defensible inner bailey in the south-west quadrant of the monument. It is not known precisely when the castle was built, as a reference to the construction of a house in Sherwood Forest by Regnald de Annesley in 1220 may alternatively refer to the Norman hall half a mile north- west of the castle and incorporated into the present Annesley Hall. That the castle was built to control the forest is almost certain, and it would have commanded any road through the forest on the line of the current Annesley Road. There is also evidence to suggest that it was held by Philip Mark, who is believed to have been the inspiration for the Sheriff of Nottingham of the Robin Hood legends.”

The example of this particular Motte illustrates a broader problem in archaeological interpretation and the reliance on established categories without sufficient empirical evidence. The description indicates that the Motte is 3 meters high and lacks stonework. Despite this, archaeologists suggest it fits the traditional Motte and Bailey mould due to its classification. This kind of speculative attribution exemplifies the issue being critiqued—science should be grounded in empirical evidence rather than suppositions or forced into pre-existing categories.

Moreover, the strategic utility of this Motte is further called into question by its location. It is situated 100 meters from the nearby main highway, beyond the effective crossbow range (typically 50 to 60 meters), which diminishes its purported defensive capability. If the intent was genuinely defensive, the choice of this site appears illogical, especially when LiDAR imaging suggests that flatter and more strategically advantageous ground is available closer to the highway. This would have been a more influential position for a defensive structure intended to control or monitor the road.

The decision to place the Motte out of effective range, on the edge of a deep gully, indicates a possible misinterpretation of the site’s original purpose or a lack of understanding of the tactical demands of medieval fortifications. This scenario underscores the need for a more nuanced and evidence-based approach in archaeological practice, moving away from fitting ambiguous sites into broad, pre-defined categories without adequate justification. It suggests that alternative, non-defensive interpretations should be considered better to understand such structures’ historical and practical context.

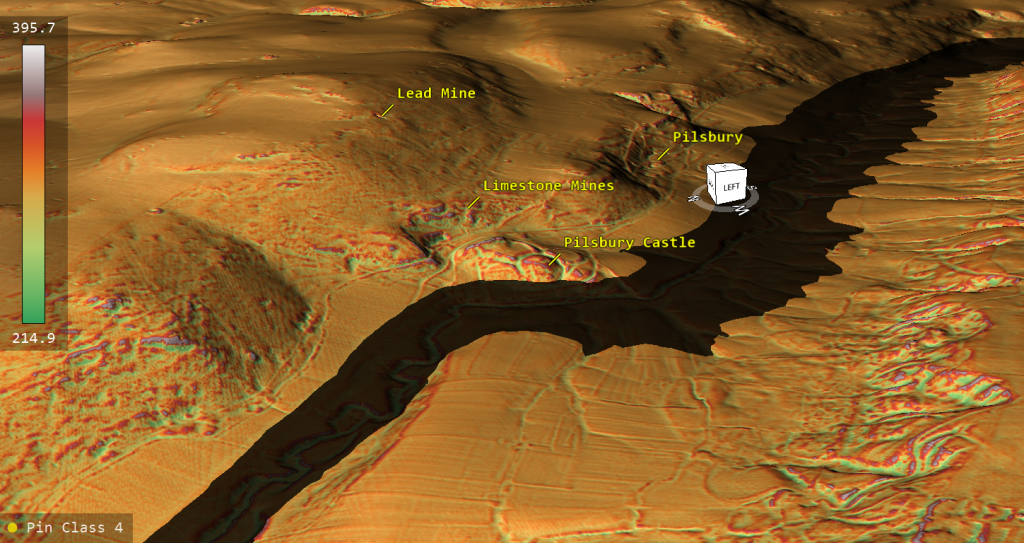

10. Pilsbury Castle – Motte and Bailey Castle

According to EH – “The monument is a medieval motte and bailey castle whose remains include a conical motte or castle mound, three baileys enclosed by ramparts and ditches, an outwork on the south side and an open area on the north side containing a variety of earthworks interpreted as the remains of pens and structures associated with the castle. The castle is situated on a spur overlooking the River Dove and utilises the steep natural slope on its north-west side as part of its defences. From this side the motte is c.12m high and the ramparts up to 10m high. From inside the castle, the motte is c.5m high and 30m wide across the top. The breadth of the summit indicates that it was the site of a shell keep; a type of castle keep in which timber buildings were arranged round the inside of a circular wall or palisade. Internally, the ramparts vary between 2m and 5m high. Internal ditches flank the ramparts of the central and south-west baileys and vary between 3m and 5m deep and 5m to 10m wide. A 15m wide ditch encloses the foot of the motte on its east and south sides and branches north-eastward along the north-west side of the north bailey where it reaches a width of 10m. The motte ditch also branches to create a 10m wide external ditch round the south side of the north bailey, where it varies between 2m and 3m deep. The north bailey is the largest and most massively defended of the three enclosures. Its ramparts are up to 5m high and a similar width across the top. Projections facing north and eastward were the sites of towers. Blocks of limestone on the surface of these projections are the remains of their foundations or, alternatively, of the curtain wall that formerly enclosed the bailey. Access into the north bailey was via a gateway through the defences on the south-east side. (Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History) A gate tower would have guarded this entrance and a curving ramp leads down into the interior of the bailey which is roughly square and has an area of 0.25 hectares. The strength of the north bailey indicates that it was the location of the main living accommodation of the lords of Pilsbury Castle, and would have included the lord’s hall and its various service buildings. The smaller central and south-west baileys, with areas of 0.15 hectares and 0.09 hectares respectively, would have contained a variety of workshops, stabling and ancillary buildings, and were most likely enclosed by timber palisades. They are separated from the north bailey by a wide ditch. A drawbridge would have existed to connect the two areas and is believed to have been located at the south-west corner of the north bailey where there is a corresponding earthwork on the opposite side of the ditch. In this way, the highly defensible motte and north bailey could be isolated in the event of attack. The main approach to the castle was via a sunken track that leads from the deserted village of Pilsbury to the south and from Crowdecote to the north. This track passes the entrance into the north bailey and is overlooked by the outwork on the south side of the castle and by the projecting towers in the curtain wall. Traffic wishing to enter the service areas of the castle – that is, the central and south-west baileys – would have circled the castle to the north and approached via a second entrance which lay to the west of the motte. Here a ramp leads from the occupation area north of the castle to a gateway into the south-west bailey. This gate is overlooked by two earthwork mounds interpreted as the sites of towers. The central bailey was then entered by turning east through another gate located at the head of the rampart dividing the two baileys. This rampart would also have carried a palisade. The precise history of the castle is uncertain but, in addition to commanding the Dove Valley between two crossing points, it may, in the last quarter of the thirteenth century, have been the centre of the Hartington estates of Edmund, Earl of Lancaster. No excavation of the site has been carried out but, in c.1880, a number of medieval artefacts were found in a cave below the castle. All modern boundary walls and fencing are excluded from the scheduling though the ground underneath is included.”

Characterising a remote site traditionally labeled as a defensive fortification, particularly one distanced from any substantial population centre, raises significant logistical questions. As noted in the Domesday Book, the nearest town was essentially unpopulated, featuring only agricultural land and meadows, which begs the question: what exactly was this fortification defending?

A deeper examination of the site’s geography and resources provides a more plausible explanation. The area, known for its limestone reef, is rich in minerals and marked by numerous caves and pits used historically for mining. The discovery of a single Norman tile in one of these caves, which helped date the site, maybe less indicative of a defensive structure and more of occasional Norman presence or activity.

Furthermore, the LiDAR mapping of the area reveals the absence of any significant roads leading to or from the so-called castle, suggesting alternative means of access and utility. A once-significant river channel nearby supports the hypothesis that this site was more likely used as a trading post. Boats could have utilised the river for transport, making the site an ideal location for trading activities associated with the mining operations. Rather than serving as a defensive feature, the area designated as a bailey might have functioned as storage for the mined materials awaiting transportation via the river.

This interpretation shifts the narrative from a traditional defensive stronghold to a commercial and industrial hub, highlighting the importance of considering all environmental and archaeological clues when assessing historical sites. Such a perspective aligns better with the geographical and economic realities and enriches our understanding of the diverse functions historical structures could serve.

(Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History)

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

(Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History)

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Prehistoric Britain Blog Review - Prehistoric Britain