Is Archaeology a dying discipline?

Contents

Introduction

There are many challenges archaeology faces as a discipline. The historical misconceptions and the evolving understanding of our past are significant aspects of archaeological study. (Is Archaeology a dying discipline?)

Here are a few reasons why archaeology can sometimes lag behind other sciences in terms of updating its theories and practices:

Funding Limitations: Archaeology often has limited funding compared to more ‘practical’ sciences like engineering or medicine. Because the immediate applications of archaeological findings aren’t always as straightforward as those in fields that can drive technological innovation or medical advancements, it might receive less investment from both the public and private sectors.

The complexity of Evidence: Archaeological evidence is often incomplete and open to interpretation. Different cultures, times, and environmental conditions can significantly alter the archaeological record, making it difficult to draw definitive conclusions. This complexity means that updating misconceptions requires much new evidence and reinterpretation, which can be slow.

Interdisciplinary Challenges: Archaeology sits at the intersection of the humanities and sciences. It relies on methods and theories from fields as diverse as anthropology, geology, chemistry, and even physics (for dating techniques). This interdisciplinary nature can make integrating new findings and methods difficult, as each contributing discipline may have its own advancements or shifts in understanding.

Public and Academic Interest: The extent to which archaeology can draw public interest often depends on spectacular finds or the promise of uncovering “lost” civilisations, which can skew perceptions of what the field is genuinely about. Academic interest can similarly focus on certain popular or well-funded areas, leaving other equally essential areas under-explored.

Heritage and Cultural Sensitivity: Archaeological work is also closely tied to heritage and cultural sensitivity issues. Respecting present-day cultures and legal frameworks surrounding archaeological sites can slow excavations and studies. Furthermore, the involvement of communities and stakeholders can complicate how sites are investigated and how findings are interpreted and shared.

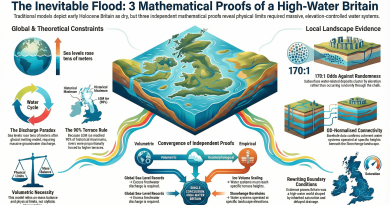

Despite these challenges, archaeology has made enormous strides in recent decades, particularly with the incorporation of technological advances such as GIS (Geographic Information Systems), LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), stable isotope analysis, and OSL (Optically Stimulated Luminescence). OSL is particularly transformative as it allows archaeologists to date the last time sediment was exposed to light, providing critical information on site use and artefact burial timing. These tools have revolutionised our understanding of ancient environments and human interactions, helping to refine our interpretations of the archaeological record. However, revising historical narratives can still be slow and contentious.

The critical issues in archaeology, such as the slow pace at which the discipline updates and corrects its understanding of historical and archaeological findings, are significant obstacles to knowledge. This can create a gap between current and public knowledge, contributing to ongoing misconceptions. Here’s a breakdown of some of the factors contributing to this issue:

Peer-Review Process: While crucial for maintaining scientific rigour, the peer-review system can be slow. This can delay the dissemination of new ideas and corrections to established theories. The process is designed to ensure accuracy and credibility, but it can also inhibit rapid progress, especially in a field like archaeology, where new findings can challenge long-held beliefs.

Publication and Communication: The language used in academic journals can be dense and inaccessible to non-specialists. This often means that even when new research is published, it may not be readily understandable to the general public or enthusiasts without a deep background in the field. This can lead to a lag in the public’s understanding of new developments.

Conservatism in Academia: Academic institutions can be conservative in embracing new theories and approaches, particularly when they challenge the foundational understandings of the discipline. Scholars who have built careers on specific interpretations may be reluctant to accept new evidence contradicting their views.

Educational Outreach: There is often a lack of effective communication between archaeologists and the public. This can be due to a lack of resources dedicated to public engagement or focusing on academic publishing over public education. Without active efforts to translate new findings into accessible formats, misunderstandings and outdated perceptions persist.

Integration of New Technologies and Methods: Although new technologies like OSL and GIS have transformed archaeological methods, integrating these into traditional studies and ensuring they are part of the standard curricula across universities can be slow. This delay affects how quickly new findings influenced by these technologies become part of the mainstream archaeological discourse.

Addressing these issues requires a concerted effort to improve the speed and accessibility of the peer-review process, enhance public engagement and education, and encourage a more dynamic acceptance of new technologies and methodologies within the academic community. Efforts to make research more accessible and to engage directly with the public can help bridge the gap between current archaeological research and public understanding.

Practical Examples

Wansdyke

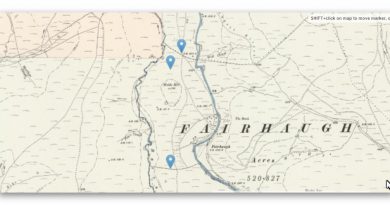

Consequently, one would imagine that the information contained within the publication would have created a ‘talking workshop’ in which questions would be asked and thoroughly discussed in minute detail as it is new to the world and previous undiscovered – but at best, all it received as a ‘Conspiracy Theory’ label even though it was based on research using the most up to date 21st Century software through LIDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) data collected by the government through is Defra (Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs) website, which has yet to be embraced by the archaeological profession, who still rely more upon dated Satellite technology and crop marks for information.

So, the professionals were reticent, and the only noise from social media was the usual archaeological ‘Jihads’ who refused to accept that the books and courses they attended and read in the last century are no longer relevant or correct as they were then ‘peer reviewed’ and therefore (in their mind) absolute in accuracy, for the rest of time no doubt?

This kind of ‘blind obedience’ is sadly commonplace and can be seen by religious fundamentalists, who take the words from a book and turn them into a test of faith rather than knowledge. ‘Intelligent design’ is a classic response to scientific proof of evolution, and the tactics used by these people are similar to what I see in my work – attempting to disprove a substantial theory by seeking a show that all aspects of evolution have been fully explained (although subjective in nature) and there cancels the hypothesis by default.

One of these ‘diehards ‘ came back at me in the hope that if he could show doubt in just one site – then the whole hypothesis would come tumbling down, even though a book covering every single metre of East Wansdyke has proven beyond any reasonable doubt that Wansdyke was neither a defensive wall nor a boundary marker. He’s claim was that Wansdyke was built on a ‘late iron age’ fortification and therefore must be Saxon.

So to prove his point, he named a site not actually covered within East Wansdyke book but in an area called West Wansdyke, which I questioned its relevance within the book as I concluded it was connected at a later date to the original prehistoric canal system (probably by the Roman’s) as it was incomplete, sporadic and of a different specification to East Wansdyke.

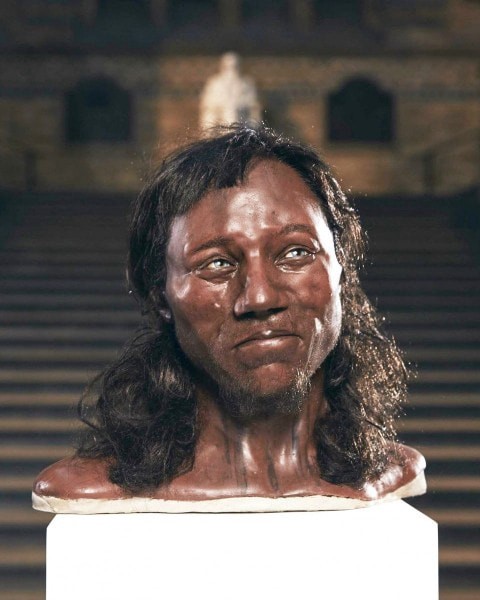

Cheddar Man

A recent discovery in Britain involving the analysis of mtDNA (mitochondrial DNA) from the skeleton of a Mesolithic man found in the Cheddar Gorge, Somerset, England, has sparked considerable debate. According to researchers, this ancient individual, who lived around 9,000 years ago, likely had dark (brown-black) skin, dark brown hair, blue eyes, and phenotypical features resembling those of Western Europeans. But what’s the issue with these findings?

Without delving too deeply into the genomic research, the problem lies in the comparison with data collected over two decades ago when mtDNA collection began in 1996. This earlier study, which was notably not peer-reviewed, has been flagged in subsequent reports for potential modern DNA contamination during the collection process.

The 2018 Analysis and Its Controversy

The more recent study, which analyzed a skull fragment in 2018, found that Cheddar Man’s remains were linked to the same ancestral family as other Mesolithic European populations. This conclusion itself isn’t particularly surprising. However, the lack of peer-review for the initial study raises concerns about the legitimacy of these findings. The publication of detailed chromosomal data related to hair, eye, and skin color—especially given its potentially questionable origins—seems to have been aimed more at garnering publicity than advancing scientific understanding.

Even if the initial DNA was uncontaminated, the science behind estimating physical traits such as skin tone is not fully proven and remains a working hypothesis. Notably, 60% of the necessary chromosomes for accurately estimating skin tone were missing. Consequently, at best, there was only a 60% chance of the assessment being correct. Scientific standards dictate that results with a probability rate of less than 50% should not be considered reliable, as they are statistically likely to be incorrect.

The Media Hype and Its Consequences

Despite these uncertainties, the announcement led to the creation of ‘scientifically based’ documentaries suggesting that dark-skinned men with dreadlocks, akin to black Rastafarians, populated Ireland 10,000 years ago. This narrative, built on what many consider ‘bad science,’ has provided the establishment with political ‘brownie points’ on social media. Previous studies, such as “Genomic structure in Europeans dating back at least 36,200 years” (Science DOI: 10.1126/science.aaa0114), have shown…

The rush to publish sensationalized interpretations without thorough peer review undermines the integrity of archaeological and genetic research, leading to public misinformation and unfounded historical reconstructions.

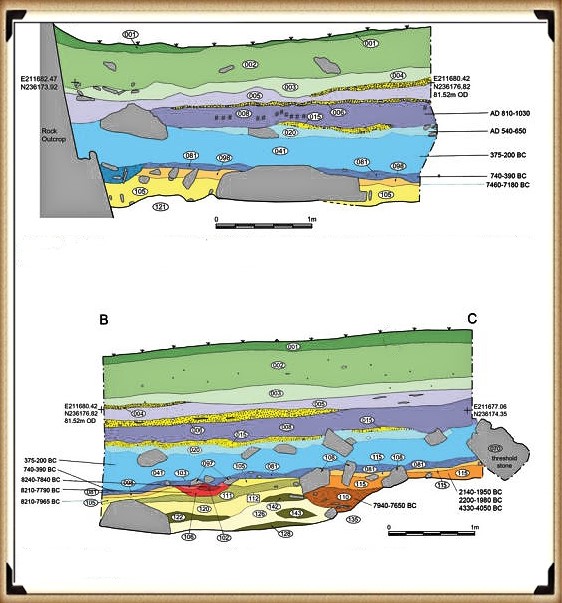

Craig Rhos-Y-Felin

The Craig Rhos-y-Felin report by Mike Parker-Pearson is riddled with inconsistencies and logical inaccuracies, largely because the layout of the site was not thoroughly considered. One significant detail is the river that runs adjacent to the quarry, which was present as far back as 5620–5460 BCE and possibly up to 1030–910 BCE.

The River and Quarry Relationship

According to the report, “Most of the site was then covered by a layer of yellow colluvium (035), dated by oak charcoal to 1030–910 cal BC (combine SUERC-46199; 2799±30 BP and SUERC-46203; 2841±28 BP). This deposit is contemporary with the uppermost fill of a palaeochannel of the Brynberian stream that flowed past the northern tip of the outcrop. Charcoal of Corylus and Tilia from the basal fill of this palaeochannel dates to 5800–5640 cal BC (OxA-32021; 6833±40 BP) and 5620–5460 cal BC (OxA-32022; 6543±37 BP), both at 95.4% probability.”

This suggests that the stream feeding into the River Nevern flowed during the Mesolithic period, reaching the quarry outcrop rocks and remaining close by until around 1000 BCE. Consequently, the transportation of newly quarried stones to Stonehenge likely involved boats, similar to stone transportation methods used in other ancient civilizations like Egypt.

Evidence of Quarrying and Hearths

The site layout also indicates the period when the stones were genuinely quarried. A single monolith ready for transportation lies on the east side of the site, with human-made hearths a few meters south of it—exactly where one would expect them. These hearths, however, are from the Mesolithic period, with three dating back to 8550–8330 BCE, 8220–7790 BCE, and 7490–7190 BCE. Yet, the report asserts:

“There is no evidence of any Mesolithic Quarrying or working of Rhyolite from this crop.”

This claim is scientifically dubious. How can one distinguish Mesolithic from Neolithic tool marks when the same tools might have been used? And what activities do archaeologists believe took place at the quarry over those 1,300 years if not quarrying?

Questioning the Scientific Approach

The establishment seems intent on highlighting only two of the 42 carbon dates obtained from the site, disregarding the other 40 as irrelevant. This approach is considered ‘bad science,’ aiming to preserve the traditional model at the expense of genuine scientific inquiry.

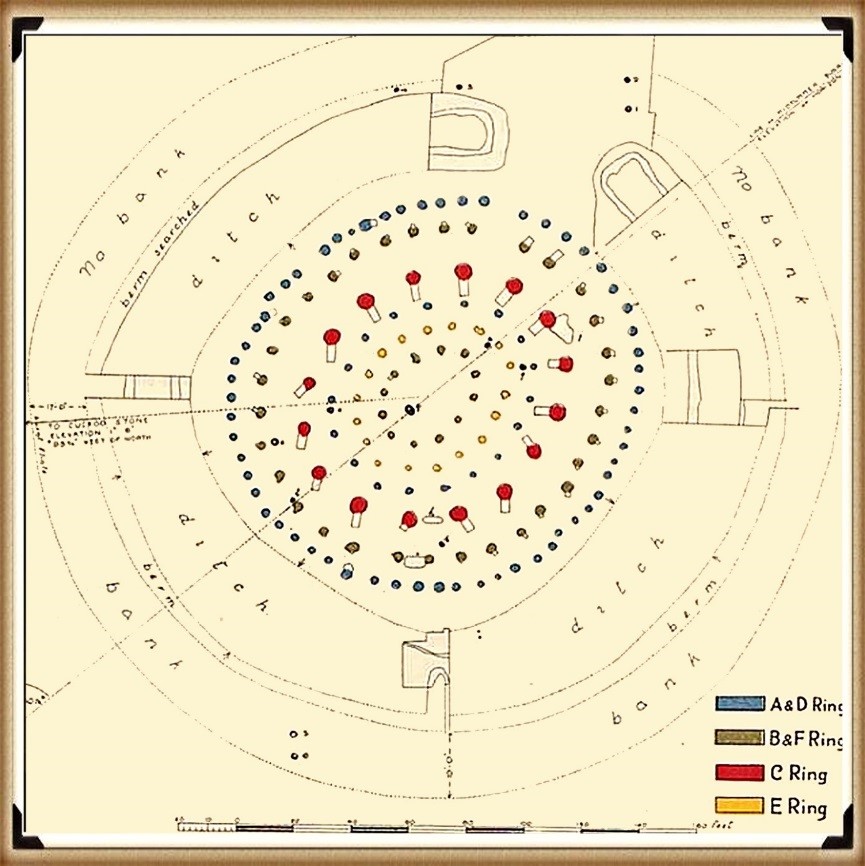

Woodhenge

The traditional reconstruction of Woodhenge presents yet another example of flawed science in archaeology. Despite the ‘second rate’ excavation report from the 1920s, modern archaeologists have concluded that this structure was a single-story house or an ‘artistic forest’ of tree stumps. However, a closer examination of the evidence leads to a different and more accurate understanding of this structure.

Site Layout and Post Holes

The site’s layout, though lacking in detail, reveals significant understatements in its reconstruction. The original excavation plans show that the existing ‘concrete’ posts are far too small. A more recent excavation by Pollard in 2007 indicates that the original post holes are at least five times larger than the current representations.

Misinterpretation of Ramps

A crucial unanswered question is the purpose of the large ramps by the post holes. These ramps would have added at least another month to the construction time and 500 working hours, suggesting their necessity. The direction in which these ramps were cut, a detail overlooked or ignored by archaeologists, provides important clues. The massive 4-5 ft pine posts in the 16 postholes (known as the C Ring) would weigh 214 kg per foot of length. Several healthy adults could easily handle a single-story pole without the need for a large ramp, indicating that the poles were significantly taller.

Clues from the Site Plan

The site plan also hints at the poles’ length. The angles of the ramps into the giant postholes are not uniform, suggesting a specific order of erection to avoid interference between the poles. This indicates that the poles at Woodhenge were likely over 100 ft high, if not taller.

Dating and Sample Issues

The dating of Woodhenge (and Durrington Walls) to around 2400 BCE is based on unrelated antler and bone fragments, which is convenient but problematic. Most of the post hole samples from the 1926 to 1929 excavations were either lost or stored away and have not been tested since. Similar issues were found with pine charcoal samples taken from the old car park in 1966, which were initially not carbon-dated and declared Neolithic. However, it was later discovered that these samples were actually Mesolithic, dating to around 8100 BCE. This raises questions about the pine charcoal dates found at Woodhenge, which were also not carbon-dated, supporting the traditional model without proper verification.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

Other Blog Posts

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Blog Post Review - Prehistoric Britain