South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

Contents

Introduction

According to Wikipedia

Cadbury Castle is a Bronze and Iron Age hillfort in the civil parish of South Cadbury in the English county of Somerset. It is a scheduled monument[1] and has been associated with King Arthur‘s legendary court at Camelot.

The hillfort is formed by a 7.28 hectares (18.0 acres) plateau surrounded by ramparts on the surrounding slopes of the limestone Cadbury Hill. The site has been excavated in the late 19th and early 20th century by James Bennett and Harold St George Gray. More recent examination of the site was conducted in the 1960s by Leslie Alcock and since 1992 by the South Cadbury Environs Project. These have revealed artifacts from human occupation and use from the Neolithic through the Bronze and Iron Ages. The site was reused by the Roman forces and again from c. 470 until some time after 580. In the 11th century, it temporarily housed a Saxon mint. Evidence of various buildings at the site has been unearthed, including a “Great Hall”, round and rectangular house foundations, metalworking, and a possible sequence of small rectangular temples or shrines.

Location

Cadbury Castle is located 5 miles (8.0 km) north east of Yeovil. It stands on the summit of Cadbury Hill, a limestone hill situated on the southern edge of the Somerset Levels, with flat lowland to the north. The summit is 153 m (500 ft) above sea-level on lias stone.[9][10]

The hill is surrounded by terraced earthwork banks and ditches and a stand of trees. On the north west and south sides there are four ramparts, with two remaining on the east. The summit plateau covers 7.28 hectares (18.0 acres),[11][12] and is surrounded by the inner bank which is 1.2 kilometres (0.75 mi) long.[13] The hill fort is overlooked by Sigwells, a rural plateau rich in archaeological remains. Due to scrub and tree growth the site has been added to the Heritage at Risk Register.[14][15] Further information on the dig and hill fort can be found a short walk down the road on Somerset Heritage Panels which have been erected in the local pub The Camelot Inn.[16]

Excavations/History

Early Occupation

The earliest settlement on the site is represented by pits and post holes dated with Neolithic pottery and flints.[17] These are the remains of a small agricultural settlement which was unenclosed.[18] Bones recovered from the site have been radiocarbon dated to 3500 and 3300 BC.[11] A bank under the later Iron Age defences is likely to be a lynchet or terrace derived from early ploughing of the hilltop. The site was also occupied in the Late Bronze Age, from which ovens have been identified.[19] Radical revisions of the Bronze Age archaeology on the lower slopes[20] resulted from discoveries during excavations and survey work by the South Cadbury Environs Project.[21] Finds include the first Bronze Age shield from an excavation in northwest Europe, an example of the distinctive Yetholm-type. Carbon dating implies that the shield was deposited in the 10th century BC, although metallurgical evidence suggests that it was manufactured two centuries earlier.[22][23] A metal-working building and associated enclosure were discovered 2 km (1.2 mi) south east of the hillfort, roughly contemporary with the period of manufacture.[24]

Human occupation continued throughout the Iron Age.[12] A stone enclosure was constructed around 300 BC with timber revetting, and ploughing ceased within the hilltop site. Excavations have shown the signs of four and six post rectangular buildings which were gradually replaced with roundhouses.[18] Large ramparts and elaborate timber defences were constructed and refortified over the following centuries. Excavation revealed round and rectangular house foundations, metalworking, and a possible sequence of small rectangular temples or shrines,[25][26] indicating permanent oppidum-like occupation.[27] Excavations were undertaken by local clergyman James Bennett in 1890 and Harold St George Gray in 1913, followed by major work led by archaeologist Leslie Alcock from 1966 to 1970.[11][28] He identified a long sequence of occupation on the site and many of the finds are displayed in the Museum of Somerset in Taunton.[22] The finds from the Late Bronze Age to the Early Iron Age, exploring the ramparts and southwestern gate structure, represent one of the deepest and most complex Iron Age stratigraphic sequences excavated in southern Britain.[29]

Castle

During the first century BC, additional lines of bank and ditch were constructed, turning it into a hill fort which is now known as the castle.[18] There is evidence that the fort was violently taken around AD 43 and that the defences were further slighted later in the first century after the construction of a Roman army barracks on the hilltop.[30] Excavations of the southwest gate in 1968 and 1969 revealed evidence for one or more severe violent episodes associated with weaponry and destruction by fire.[31] Leslie Alcock believed this to have been dated to around AD 70,[32] whereas Richard Tabor argues for a date associated with the initial invasion around AD 43 or 44.[33] Michael Havinden states that it was the site of vigorous resistance by the Durotriges and Dobunni to the second Augusta Legion under the command of Vespasian.[34] There was significant activity at the site during the late third and fourth centuries, which may have included the construction of a Romano-British temple.[35]

Post-Roman Occupation

Following the withdrawal of the Roman administration, the site is thought to have been in use from c. 470 until some time after 580.[11] Alcock revealed a substantial “Great Hall” 20 by 10 metres (66 ft × 33 ft) and showed that the innermost Iron Age defences had been refortified, providing a defended site double the size of any other known fort of the period. Shards of pottery from the eastern Mediterranean were also found from this period, indicating wide trade links.[36][37] It therefore seems probable that it was the chief fort of a major Brythonic ruler, with his family, his warband, servants, and horses.[38] Between 1010 and 1020, the hill was reoccupied for use as a temporary Saxon mint, standing in for that at Ilchester.[11][39][40][41][42]

Maps

1800s OS Map

GE Satellite Map

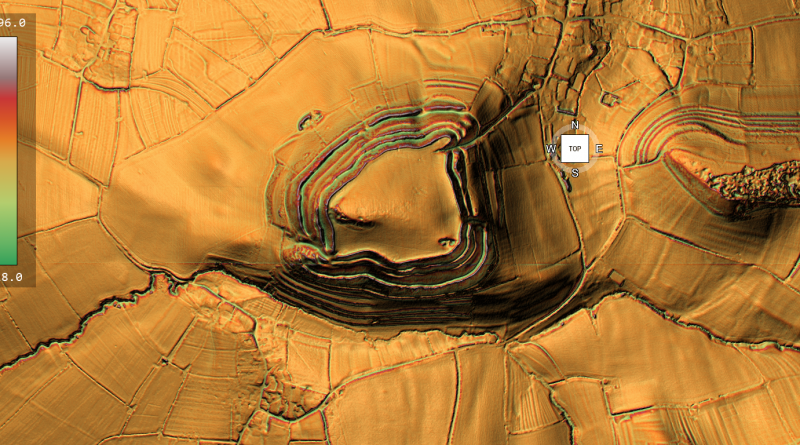

LiDAR Map

Investigation

Site Flyaround

Site Flyover

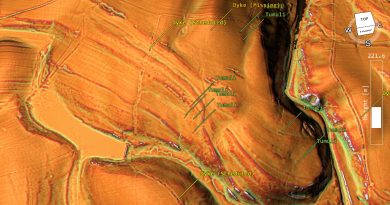

Lidar Map showing Bronze Age

LiDAR Map showing Mesolithic Period

Defence Strategy 101

Roman Defence System

Roman defences (of the same period as the ‘Iron Age’ ), we notice the ditches were relatively small and narrow. These ditches were called ‘Ankle Breaker’ as the purpose was for the assailant to fall into the ditch (usually containing pointed wooden stakes to either injure or kill the assailant) or to at least break their ankle from the fall, making them immobile. These ditches would be 3 to 4 m wide and about 2m deep and could be dug quickly.

The soil excavated from the ditch would be placed on the defensive side to elevate the defenders, allowing them to look down and fight their attackers from a higher position. Simply standing on elevated ground without a barrier would make defenders easy targets. Therefore, they built fortifications using wooden stakes or stone for more permanent and substantial defences. These fortifications provided cover from spears, arrows, or stones while looking down into the conflict zone. This basic defensive strategy has remained unchanged for thousands of years, as seen with the Normans, who used castles and moats. The moats slowed down assailants, allowing defenders to use crossbows effectively against anyone attempting to cross the deep waters.

Lidar Maps of Sth Cadbury Castle Show No Defences

Banks

The banks at South Cadbury Castle show no signs of palisades on top of the bank at any stage before the Roman occupation, which brought stone to the very top of the site. The other four banks appear to be quite flat, as if they have been used for walking upon rather than holding any defensive wooden structures or ‘foxholes.’

Importance and Use of Foxholes in Defense

Concealment and Protection: Foxholes are small, dug-out trenches or pits used by soldiers to provide cover and concealment. They protect defenders from enemy fire and other dangers. By being below ground level, soldiers can remain hidden and minimize their exposure to enemy attacks.

Historical Use: Throughout history, foxholes have been a crucial part of defensive strategies in various military contexts: While the term “foxhole” is modern, the concept of digging protective pits or trenches has been used in various forms throughout history. In ancient battles, soldiers would dig pits to defend against archers and other ranged weapons.

Advantages of Foxholes

- Reduced Visibility: Soldiers in foxholes are less visible to the enemy, making it harder for attackers to target them.

- Protection from Spears, Rocks and Arrows: Being below ground level the size of the target is greatly reduced.

- Stability for Firing: Foxholes provide a stable firing position, allowing soldiers to fire and use their weapons more accurately.

South Cadbury Castle Context

The absence of evidence for palisades or foxholes at South Cadbury Castle before the Roman occupation suggests a different use or purpose for the banks. Instead of being purely defensive, the flat banks must have served other functions.

Ditches

Looking at the construction of the ditches at South Cadbury Castle, we notice that it has no defensive features as expected from a so-called ‘Iron Age Fort’. The ditches are far too broad to be defensive (15m to 30m wide) compared to Roman ‘Ankle Breaker’ of 2m to 3m. The maps show no sign of a wooden or stone barrier, and archaeological excavations have found no evidence of post holes or defensive pits on the banks. Moreover, the Ditch is banked on the wrong side to be defensive, as if it has been built to encase a watery moat. This outside bank would protect any assailants attacking, giving them ample bank coverage. The internal aspect of the Ditch shows no sign of any wooden defensive poles or post holes as seen in Roman Ditches and is designed without internal walls allowing assailants from using the Ditch as cover and the facility to wander around the circumference undercover, testing the weaknesses in the defence. Therefore, as a defensive feature, these types of ditches on so-called ‘Iron Age Forts’ are fundamentally flawed and commonplace.

The LiDAR Maps also show that the ditch of the ditches indicate that they were built for water, as shown by the blue on these images – this then allows us to look at the design of the earthwork in detail, which shows that the banks have been cut by not roads but other ditches. These ditches that cut across the circumference moats cut into them that, suggest that if water had been contained in these ditches, then the vertical dykes could have been used to gaol boats up from the bottom of the dyke ditch to one of these upper moat levels. These same LiDAR maps also show how the soil was distributed to the outside of the moats to enhance and make the feature deeper.

Water Table

This hypothesis of using these ditches as moats can only be proven if we find the natural springs that could have fed these earthworks in the past. We know from our studies into rivers, such as The Thames and Avon, that they were both much higher and of greater volume in the past, and this height was retained for thousands of years after the last ice age. This enhanced height and volume is reflected and caused by a higher water table. Within these water tables, natural springs are formed, and water leaks into the land, creating rivers and streams. Although we do not have geological information that allows us to trace past springs, we find existing springs in this location (still active today), which suggests our hypothesis is correct.

Dykes

As we have already suggested, the lack of defensive features shows that this is far from being a fortification; instead, it was used as a trading site with moats to facilitate the mooring of boats. The transportation to these moats was achieved by other earthworks called Linear Earthworks (also known as Dykes). Dykes were introduced when the river shorelines of the Prehistoric fell with the water table, and they wanted to continue to use these established trading sites rather than having to build new sites at a lower level. So, Dykes were built (like roads) to transport goods to market and also minerals extracted from the many quarries which uncommonly surround these Dykes. Here in South Cadbury Castle, we see not only Dykes feeding the local quarry sites but also placed on the side of this Trading site to allow access to the moats for the boats coming off the rivers, ready for unloading/loading.

To reinforce the use of this site as a trading The site as a trading place has a second vertical earthwork identified through LiDAR technology. This secondary slipway is distinguishable from the initial structure by its lack of connection to a dyke or river. The slipway appears to traverse from the lowest moat up to the top of the site. While photographs may provide a visual reference, the full extent and significance of this feature are best understood through LiDAR models, which enhance the landscape to reveal these historical elements with greater clarity.place, a second verticle earthwork has been identified via LiDAR technology is a secondary slipway, distinguishable from the initial structure by its lack of connection to a dyke or river. This slipway appears to traverse from the lowest moat up to the top of the site. While photographs may provide a visual reference, the full extent and significance of this feature are best understood through LiDAR models, which enhance the landscape to reveal these historical elements with greater clarity.

Dating the Site

Archaeologists are puzzled by the unexpected dates of this site at South Cadbury Castle, the site that was originally thought to be Iron Age from its classification. Therefore, the discovery of Neolithic pits at the site challenges their previously held beliefs about its functions. However, instead of reconsidering their perceptions, they instead provided speculative explanations for these out-of-time artifacts and features. For example, they have described a bank beneath the Iron Age defenses as a “lynchet or terrace derived from early ploughing,” even though there is no carbon dating evidence to support this claim. In reality, this site is likely to be Neolithic, and the ‘lynchets’ could be Mesolithic banks, indicating its true age.

The discovery of the Bronze Age shield is also an indication of the status of the site and its trading routes – as only one has been found, this would indicate that it was part of the trading or personal ownership of someone in the 10th Century BC at this site. This suggests that this was trading could have been at a much earlier date than current archaeologists suggest, which could too have been with the Mediterranean and a possible source of this unusual artefact, as indicated by the other finds from the late saxon period.

Function of the site

The fact that in the East of this site is one of the largest quarries in Somerset and that the Saxons used the fort as a mint just over a thousand years ago proves that the site’s function was a mineral extraction and trading point. This extraction goes back to the Mesolithic period shown on LiDAR maps with a natural harbour by the Quarries and then Dykes to the Trading site as the prehistoric waters fell. No doubt (as the banks are found not to be defensive), the fort was fortified later during the Roman period with Stone as it was to keep the valuable minerals safe but not as a defensive barrier of warfare as suggested. This would explain the minor disturbances and deaths at a single gate as raiders would have attempted to steal the valuable minerals it contained in its workshops, as described by archaeologists.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Blog Post Review - Prehistoric Britain