Extreme Weather & Ancient Subterranean Shelters

Contents

Introduction

The UK media has, in recent years, frequently showcased extreme weather events, emphasizing the devastation wrought on local communities and individuals. Such reporting is often supplemented with statistical analyses of rainfall amounts and wind speeds when it comes to flooding. The phrase “since records began” is strategically employed to underline the severity of these events, often subdividing the year into categories such as the wettest summer, winter, spring, or autumn.(Extreme Weather and Ancient Subterranean Shelters).

However, it is worth noting that the Meteorological Office’s official records only date back to 1914. Describing any recent weather phenomenon as “record-breaking” can, therefore, create a misleading impression, inadvertently feeding narratives aligned with the “climate change” lobby and a “political agenda that has dominated our politics for the last 20 years.” While the England and Wales Precipitation series, which tracks rainfall and snow, dates back to 1766, and the Central England Temperature series has been maintained since 1659, these historical records, often compiled by amateur meteorologists, are frequently overlooked.

Consider this excerpt from Sky News in 2012: “England and Wales have seen the wettest summer for 100 years, according to MeteoGroup. Rainfall for June, July, and August was 362mm (14.25in), making it the wettest summer since 1912. The average summer rainfall across the UK is 226.9mm (8.9in).” MeteoGroup forecaster Nick Prebble stated, “This summer is set to be the fourth wettest since records began in 1727. The record for the UK’s wettest summer is 1912 when 384.4mm (15.1in) of rain fell.”

The Met Office added that this summer was also likely to be among the dullest on record, with only 399 hours of sunshine up to August 28, making it the least sunny since 1980. Sky News weather producer Joanna Robinson explained, “This is because the jet stream position over the summer has allowed areas of low pressure to track across the UK, when they would typically be steered further north.”

Yet, a closer examination of the statistics reveals a different picture. For example, while 2007—the second wettest summer since 1912—was a washout, its annual rainfall was far from record-breaking, ranking only 17th in the past century. Rainfall has fluctuated consistently over the last 250 years, with the most concentrated period between 1870 and 1880. This challenges the narrative that recent weather anomalies are unprecedented. (Extreme Weather and Ancient Subterranean Shelters)

Extreme Weather

The narrative around “changing” winds and gales also benefits from historical context. One of British history’s most devastating weather events was the ‘Grote Mandrenke’ or “the great drowning of men” in January 1362. This massive southwesterly gale swept across Europe, causing at least 25,000 deaths and widespread destruction. Churches with towers, such as the wooden spire of Norwich Cathedral, were notably affected. The storm surge it triggered reshaped the European coastline, devastating ports along the East Coast of England and across the North Sea.

Such events are far from isolated. Since the Mesolithic period after the last Ice Age, Britain’s inhabitants have faced much harsher conditions. The melting ice caps from the previous Ice Age released an astonishing volume of water—3.2 million millimetres—dwarfs any rainfall levels recorded in the past 250 years. This deluge shaped the landscape, creating riverbeds and flood plains that continue to influence flooding patterns today, such as the Somerset Levels.

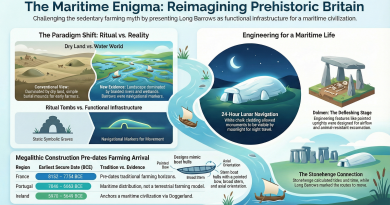

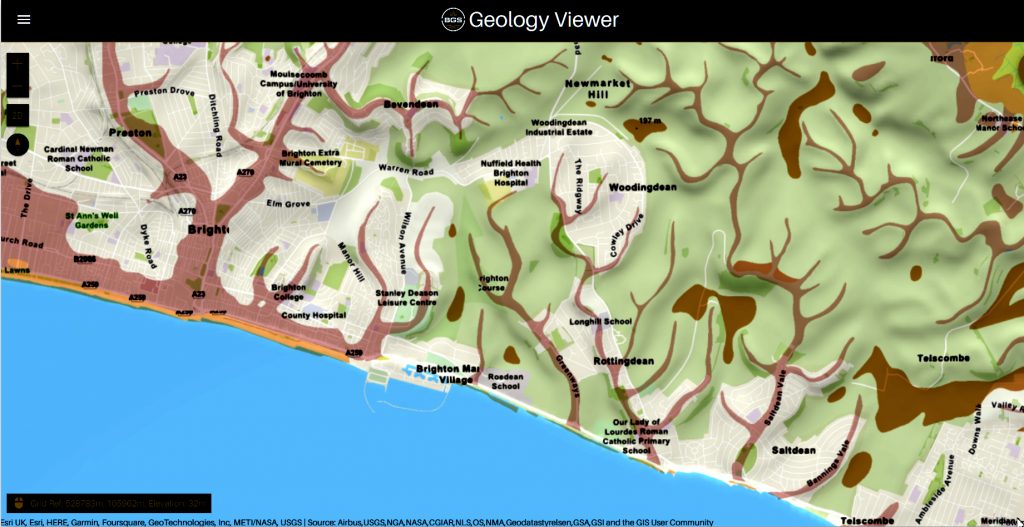

Geological evidence further supports this. Maps from the British Geological Society (BGS) reveal networks of sediments—sand, silt, and gravel—underlying floodplains, remnants of ancient river systems. These so-called “dry river valleys” were likely formed during the melting phases of the Ice Age. However, the exact timing of their formation remains debated.

For instance, modern geologists have proposed that these valleys resulted from water flooding during post-Ice Age melting rather than being shaped by ice directly. This can be seen in regions like the South Downs and Stonehenge, where chalk bedrock and ancient sediments are prominent. Exposed cliff faces along the South Downs provide a cross-section of these prehistoric waterways, with sandy sediments embedded within chalk formations.

Yet, some mysteries persist. If these dry valleys are as ancient as suggested, why are 18 inches of topsoil still present today? This discrepancy raises questions about the accuracy of the dates attributed to these features and the rate of topsoil erosion. (Extreme Weather and Ancient Subterranean Shelters)

Archaeological evidence further aligns with this geological narrative. Ancient monuments like Woodhenge and Durrington Walls were strategically constructed near these floodplains, suggesting that Mesolithic communities were aware of the changing landscape and adapted their activities accordingly. They likely used the flooded plains as waterways to navigate and connect settlements.

Ultimately, the evidence points to a complex interplay of natural and historical factors influencing Britain’s weather patterns and landscape. While modern media often sensationalize extreme weather, a deeper understanding of historical context reveals that such events are neither unprecedented nor wholly attributable to recent climate changes. Instead, they are part of a long-standing narrative of adaptation and resilience in the face of environmental challenges. (Extreme Weather and Ancient Subterranean Shelters)

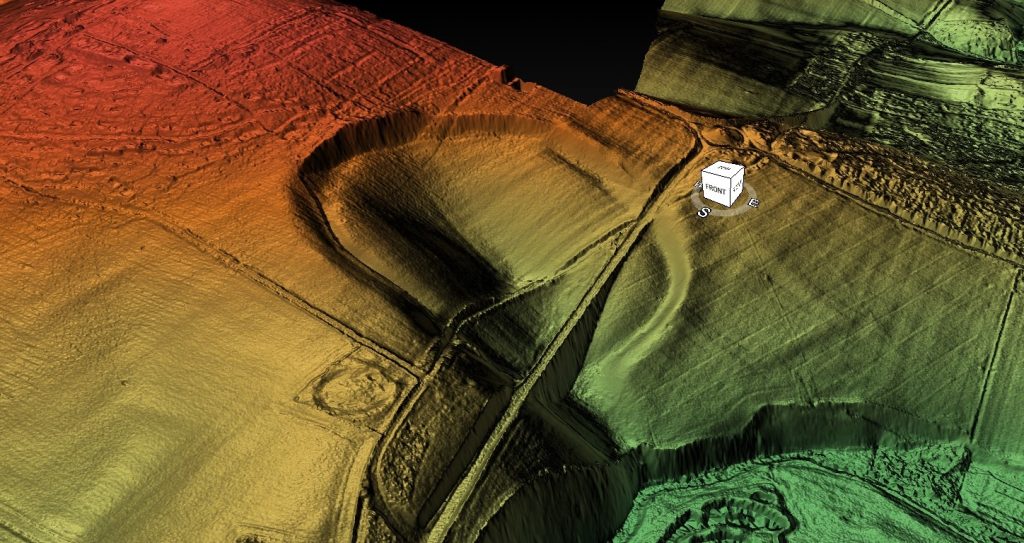

Durrington Walls

When you look at Durrington Walls, the first thing that strikes you is that it seems incomplete; it looks like a half-circle from aerial photographs, and from the ground you get, a sense of it only being half-finished. However, most illustrations include the easterly section because magnetometer surveys show that there are more ditches under the surface, although you might question their purpose, as it is not apparent. The easterly side of the site was clearly built much later than the original Westside. The East bank is smaller and does not match the initial ditch and moat specifications, which was roughly 5.5 m deep, 7 m wide at its bottom, and 18 m wide at the top. (Extreme weather and Ancient Subterranean shelters)

The bank was 30 m wide in some areas. The bank and ditch indicated by the magnetometer surveys are less than half that depth; the bank is only about a third of the size of that on the Northern side. The current theory and plan of Durrington Walls do not stand up to investigation, for clearly, the Eastern side of the camp was added later when the prehistoric groundwater had started to recede.

So what was its original use?

To answer that question, you must look at the site’s terrain, position and layout. The first thing that hits you is that the site is not flat! In fact, it’s a huge bowl.

Archaeologists say that it is a settlement, but anyone who goes camping will tell you not to pitch your tent on a slope, and for an excellent reason: you will wake up one morning covered in water, as when it rains, the water runs downhill! So, were our ancestors foolish? If this were an encampment, the houses would frequently flood from the rain.

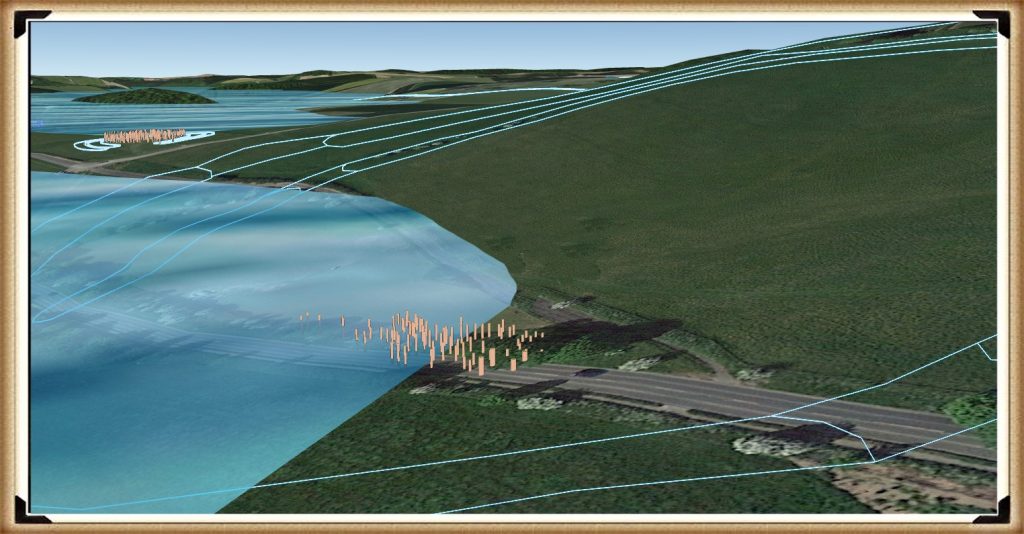

Archaeologists will insist that, because they have found the foundations of a couple of roundhouses, the site must unquestionably be a settlement – this is because its position and shape dumbfound them. However, if we now add the higher prehistoric groundwater we have suggested, the site becomes a perfect natural harbour, with shallow sides for pulling boats ashore and a four-metre deep ravine in the port centre. Moreover, it still has 3m high external walls even six thousand years after it was abandoned, imagine it when it was first built, and you would be looking at a 5m tall, 30m wide chalk wall – equivalent to any harbour wall we see today that protect our ships from the occasional Gale and storms.

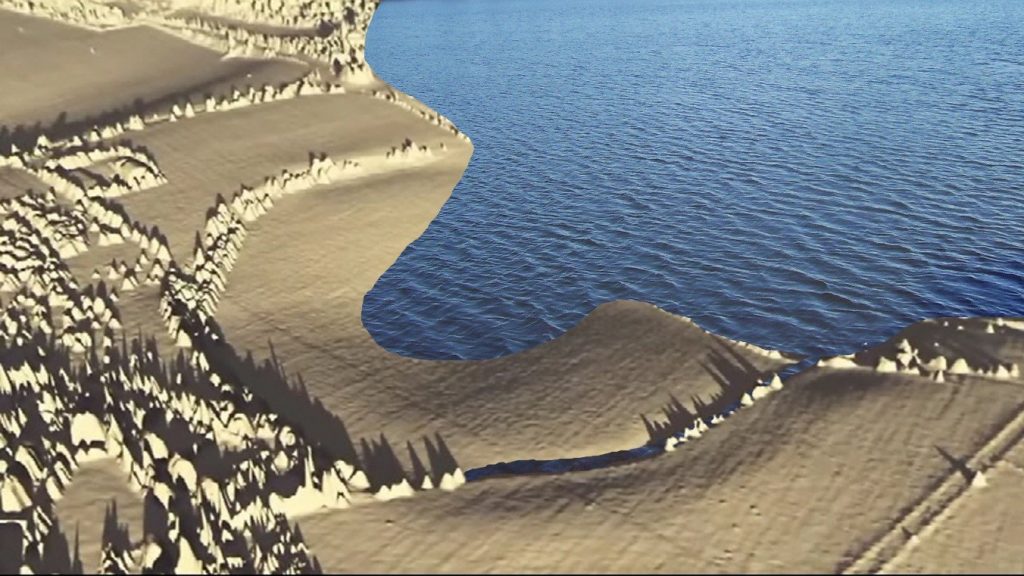

Woodhenge has two entrances: one directed towards Durrington Walls camp and, more importantly, a mysterious second entrance that trails to our ancient shoreline. This is a clear indication that groundwater was present at Woodhenge during prehistoric times. Not only would it explain the strange shape of the camp, but also the magnetometer survey showing a ditch dug after the groundwater had fallen over the years. Even more interesting is how the landscape reflected the receding shoreline over 5,000 years at this site. The present-day minor road runs along the course of the ancient shoreline circa 6,000 BCE

We should not be too surprised by this, as lakeshores and coastlines still have paths along with them today so that we can fully enjoy them. There is no reason to believe that prehistoric people did any different 8,000 years ago, and such a path would also have a practical purpose as the shorelines were used as a mooring site. If we are correct about the road and the mooring points, is it possible to find post holes here under the ground?

Unbelievably, the answer is yes!

Wainwright, in his excavations of Durrington Walls, discovered lots of them. Without a shoreline, the post holes would look random and not make much sense. However, as soon as the groundwater flooding is added, their function becomes apparent: they held mooring posts, as that is the natural landing area for boats coming to and from Stonehenge, Avebury or Old Sarum. But are there other sites that have walls to protect them from the weather? (Extreme Weather and Ancient Subterranean Shelters)

Avebury

Avebury lies in an area of chalkland in the Upper Kennet Valley, at the Western end of the Berkshire Downs, which forms the catchment for the River Kennet and supports local springs and seasonal watercourses. The monument stands slightly above the local landscape, sitting on a low chalk ridge 160 m (520 ft) above sea level; to the East are the Marlborough Downs, an area of lowland hills. Archaeologists freely admit that the history of Avebury before the construction of the henge is uncertain because little datable evidence has emerged from modern excavations. However, stray finds of flints at Avebury, dated between 7,000 and 4,000 BCE; indicate that the site was visited in the late Mesolithic period.

Post Glacial Flooding ten thousand years ago left a landscape rendered unrecognisable by groundwater, as the Avebury Circle almost becomes an island, with a large freshwater river running to the West of the site. When the groundwater started to recede, our ancestors tried to keep their monument an island by adding ditches with large banks. Current archaeological estimates suggest that it took 1.5 million working hours to build the Avebury monument.

In simple terms, that’s 200 people working full-time for three to four years. Which sadly contradicts another estimation of nearby working hours Silbury Hill, which contains 248,000 cubic metres of chalk, and would have taken 18 million working hours to construct? That’s equivalent to 500 people working full-time for 15 years. However, we are expected to believe that Aveburys 125,000 cubic metres of chalk took just 1.5 million working hours to move. (Extreme weather and Ancient Subterranean shelters)

This is just another fact that does not make sense! –

There is just no consistency in archaeological findings; it’s all subjective, and quite frankly, wrong!

It’s more likely that these monuments grew over the course of centuries, slowly but surely, the ditches starting at just one metre but getting deeper over the next 5,000 years as the moat was cleaned out until they reached their final dimensions of 11 metres deep and 22 metres wide. This gradual process would explain another archaeological mystery that the ‘experts’ avoid – with what tools were they built?

Moreover, the most exciting aspect of this excavated ‘chalk mountain’ is that we can use it to understand why it was built. We know the original height of the chalk bank as we know how much chalk was removed from the ditch in front of the mound. On average, the ditch is 11m deep and 22m wide – which means that for every metre excavated, 132m2 was transferred to the bank. The chalk mound is much narrower than the ditch from which it was excavated; therefore, the bank would be higher than the ditches’ depth. My calculation shows that the bank would be, therefore, 15m high at least but as the chalk in the ground had been compressed over time, and the bank would have contained more air gaps, the likelihood is that the bank was 20m high at the time of completion. (Extreme Weather and Ancient Subterranean Shelters)

So why take so much time and effort to build a 15m high wall?

Some archaeologists suggest it was a ‘defensive’ feature keeping out marauding tribes. However, the wall is on the wrong side of the ditch and would assist attackers rather than help the defenders of this site. As we have seen just down the road at Durrington, they have placed a high wall on the outside of the interior of the camp to protect boats from the wind and storms, like a modern harbour. Confronted by this paradox, ‘confused‘ archaeologists reverted to the standard theme that these walls were constructed for ‘ceremonial’ reasons. Which I can only imagine has something to do with the God of pointless constructions and practices?

Again as we pointed out at Durrington, these walls are seen in current harbours to protect boats from storms, showing us that our inclement weather is not unique to this current period.

But was the weather much worse than today?

Gales that historically ravaged our lands were probably more significant and more devastating in the past, which can be seen from the shelters they built to shelter from these infrequent storms.(Extreme Weather and Ancient Subterranean Shelters)

Subterranean Shelters

According to Wikipedia

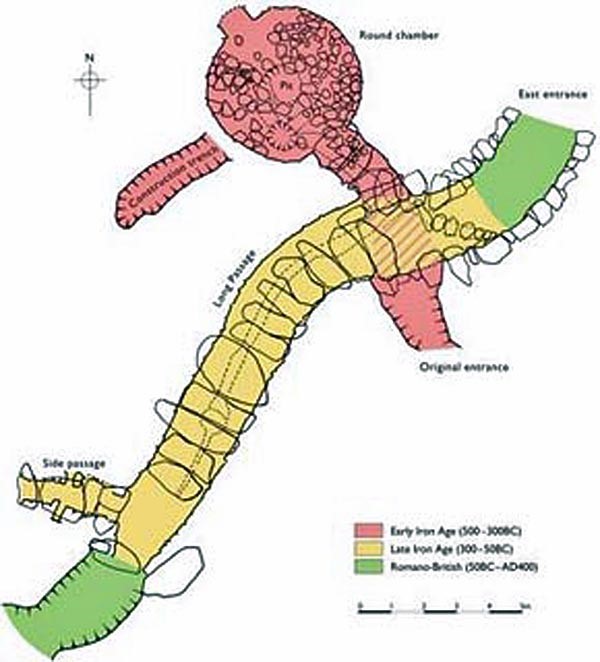

Souterrain (from French ‘sous terrain’, meaning ‘under ground’) is a name given by archaeologists to a type of underground structure associated mainly with the Atlantic Iron Age. These structures appear to have been brought northwards from Gaul during the late Iron Age. Regional names include earth houses, fogous and Pictish houses. The term souterrain has been used as a distinct term from fogou. In Cornwall, the regional name of fogou is applied to souterrain structures. The design of underground structures has been shown to differ among regions; for example, in western Cornwall, the design and function of the fogou appear to correlate with a larder use.

Souterrains are often referred to locally in Ireland simply as ‘caves’. A.T. Lucas, folklorist and Director of the National Museum of Ireland in the 1960s, published a study of the references to souterrains in the early Irish annals. An article by Warner on the archaeology of souterrains, although published 35 years ago, is still possibly the best general overview of the subject. The most comprehensive study of Irish souterrains is Clinton’s 2001 work, containing chapters on distribution, associated settlements, function, finds, chronology and no less than thirteen appendices on various structural aspects of souterrains themselves.

The name comes from the French language, which means “underground passageway.” It is sometimes used to mean ‘basement’ in languages other than English, especially in warehouses.

Souterrains are underground galleries and, in their early stages, were consistently associated with a settlement. The galleries were dug out and then lined with stone slabs or wood before being reburied. In cases where they were cut into the rock, this was not always necessary. They do not appear to have been used for burial or ritual purposes, and it has been suggested that they were food stores or hiding places during times of strife, although some of them would have had very obvious entrances.

In Ireland, they are often found inside or close to a ringfort and are thought to be mainly contemporary with them, making them somewhat later in date than in other countries. This date is reinforced by many examples where ogham stones, dating to around the sixth century, have been reused as roofing lintels or doorposts, most notably at the widened natural limestone fissure at the ‘cave of the cats’ in Rathcrogan. Their distribution is very uneven in Ireland, with the most notable concentration centred on County

The first thing that strikes you as strange is the fact that these landscape features are categorised with different names in different locations:

Earth Houses – Modern use

Fogous – Cornwall

Pictish Houses – Found in Scotland

Confusion arises here as some are only partially subterranean unlike the Earth Houses in the same region.

Caves – Ireland

It’s quite literally an archaeological mess. And the reason for this mess is those archaeologists don’t understand why they were built, so they gave them local names, unlike barrows and Stone circles and henges, which appear in the same areas but with a unified name to save confusion. So how what can we find out about these structures that will help us understand why they were built?

Location, Location, Location

If we look at the minimal archaeological evidence, we do see a defined pattern of construction. For example, in Cornwall, we have found to date a collection of fifteen ‘fogous’. According to archaeologists, this is a proposed use for fogous, a refuge during raiding trips as they are close to the sea. Sadly, if you search deeper, you see them in non-coastal areas and even in the middle of Dartmoor (Lade Hill Brook), where it’s called a Beehive Hut?

The problem with looking for such objects in Devon is that hundreds of ‘caves’ dotted around from the days of tin mining, and therefore an almost impossible to distinguish a prehistoric mine opening from a fogou.

Apart from the extreme South West of Britain, these subterranean shelters do not exist – but what of the coast of Cornwall? In prehistoric times the sea level was some 65m lower than today, and the Isle of Scilly was connected to the mainland – is there anything on these islands that could be considered a fogou?

Carn Gwavel Farm in St Marys is an underground chamber-like corbelled passage that has an `S-shaped’ curve throughout its length, which is 4.97 metres long by 1.18 metres wide and 1.18 metres high. Some roof slabs have collapsed near the northeast end of the passage and lie beneath the present floor surface. At the foot of the northeast, the end wall is a creep that formed the original entrance to the passage. The creep is 0.57 metres wide by 0.27 metres high and extends for 1.36 metres before becoming blocked by fallen debris. The fogou was discovered in May 2000 after a partial collapse of the infill between cover slabs.

The most apparent aspect of Fogous is that they are orientated to the SW-NE alignment – is this religious or a practical necessity?

A typical fogou structure is stone walls, slopping gradually inwards with height to be capped by stone lintels, forming a characteristic trapezoidal cross-section. Similar structures are found in Chamber Cairns, and Passage Chambers, which adds to the confusion as if a body is located in one of these subterranean tunnel’s archaeologists reclassify them.

In Ireland, these subterranean structures are called ‘caves’, and they are reportedly in their thousands. We also find them in Scotland as Earth Houses, although some ‘covered’ houses – not subterranean shelters- have been classified in the same category through archaeological confusion.

We know these classifications are wrong as we know what they were used for, unlike the present archaeologists – their shelters from storms.

Subterranean shelters are found in Cornwall like the isles of Scilly in abundance. But Devon has only one for sure and absolutely nothing in Dorset, Somerset or Wiltshire – where prehistoric structures such as Stone Circles, Henges and Barrows are of most significant numbers. However, we do get them in Ireland and Scotland in even more significant numbers.

But there is a problem – what happened to Wales?

Storms often batter the Welsh coast, yet according to archaeologists, there are no subterranean shelters in this part of the world; if our hypothesis is correct, there should be something similar – and there is; they’re called a Chambered Cairn and Passage Chambers. These features are found all over Wales and are similar drywall stone underground buildings, but they have found dead bodies within them with a difference.

These chambers were built thousands of years ago. Do we believe that they would continue to be used in the same way as they started?

As you drive around Britain’s countryside, you will notice ‘bunkers’ that surround current and abandoned airfields. These bunkers are only 60 years old, yet they have fallen into disuse, and farmers are using them for other purposes – should we be surprised that these subterranean shelters would be used once abandoned for other purposes such as burials?

So the map is now complete; the current storms we see that follow the ‘gulf stream’ have historically moved in from the West and Ireland and/or Cornwall moving up the Irish Sea to Scotland, lashing the Welsh Coastline. This is not new; these are prehistoric storms of which the severity was much more significant than today as the construction of these substantial shelters gives testament.

Similar construction has been seen in other countries that may indicate just how intense these storms were, and these can be found in the hurricane belt of the USA, where residents built subterranean shelters of almost the same size as our prehistoric ancestors. These shelters not only shelter people from hurricanes but the more devastating storms called tornadoes.

In prehistoric Britain directly, the ‘post-glacial flooding’ was caused by record high temperatures in this country – so like Florida today, you had sweltering ground temperatures and the vast amount of cooler water from the flooding, a perfect concoction for the tornado and the need to build substantial subterranean shelters.

But is there any other evidence that tornadoes hit Britain?

On 17th October 1091, London was hit by a vicious tornado.

Historic Records tell us the wooden London Bridge was demolished and 600 houses (primarily wooden). Furthermore, the church at St. Mary-le-bow within the city of London was smashed to pieces with rafters driven more than six metres into the ground. Two men were reported killed, and thousands were made homeless.

One of the great mysteries of Archaeology is the lack of destruction of our greatest monument Stonehenge. It was not completely pulled down, but the gigantic Sarsen Trilithon Stones toppled from a force to the SW of the Monument. It has always been believed that men had tried to pull down the monument for some obscure reason in the past – but why stop at one pair of stones?

If we look at the possibility of tornadoes in Britain, then a ‘strike’ from the South West would be probable, and that would leave the monument with one of the two trilithons felled flat and the other propped up at an angle as Stukeley found in the 16th century and was ‘repaired’ and the turn of the last century.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

(Extreme Weather and Ancient Subterranean Shelters)