Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

Case Study – Stanegate Roman Road……… (Extract from the Book – The Hadrian’s Wall Enigma)

According to Wikipedia:

The Stanegate (meaning “stone road”) was an important Roman road built in what is now northern England. It linked many forts, including two that guarded important river crossings: Corstopitum (Corbridge) on the River Tyne in the East and situated on Dere Street, and Luguvalium (Carlisle) on the River Eden in the west. The Stanegate ran through the natural gap formed by the valleys of the River Tyne in Northumberland and the River Irthing in Cumbria. It predated Hadrian’s Wall by several decades; the Wall would later follow a similar route, slightly to the north.

The Stanegate differed from most other Roman roads in that it often followed the most accessible gradients and so tended to weave around, whereas typical Roman roads follow a straight path, even if this sometimes involves having punishing slopes to climb.

A large section of the Stanegate is still used today as a modern minor road between Fourstones and Vindolanda in Northumberland.

It is believed that the Stanegate was probably built under the governorship of Agricola, from 77 to 85 AD, during the reigns of the emperors Vespasian, Titus and Domitian. It is also thought that it was built as a strategic road when the northern frontier was on the line of the Forth and Clyde. An indication of this is that it was provided with forts at one-day marching intervals (14 Roman miles or modern 13 miles (21 km)), sufficient for a strategic non-frontier road. The forts at Vindolanda (Chesterholm) and Nether Denton have been shown to date from about the same time as Corstopitum and Luguvalium, in the 70s AD and 80s AD.

When the Romans decided to withdraw from Scotland in about 105 AD, the line of the Stanegate became the new frontier, and it became necessary to provide forts at half-day marching intervals. Newbrough, Magnis (Carvoran), and Brampton Old Church were additional forts. It has been suggested that a series of smaller forts were built in between the ‘half-day-march’ forts (6.5m/10km). Haltwhistle Burn and Throp might be such forts, but there is insufficient evidence to confirm a series of such fortlets.

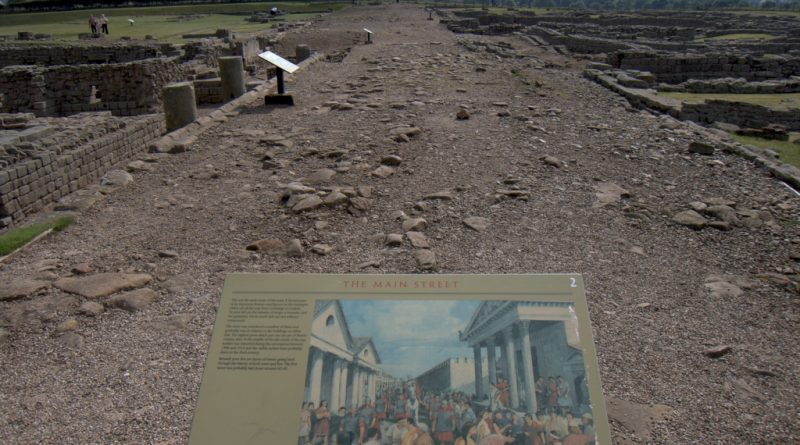

Where it left the base of Corstopitum, the Stanegate was 22 feet (6.7 m) wide with covered stone gutters and a foundation of 6-inch (150 mm) cobbles with 10 inches (250 mm) of gravel on top.

According to English Heritage

The Stanegate military road linked Corbridge and Carlisle, which were also situated on important north-south routeways. It also extended west of Carlisle towards the Cumbrian coast.

The construction of a series of forts along the road line allowed many troops to be stationed in this crucial frontier area and ensured that the site could be extensively patrolled. A series of smaller watchtowers were also built to help frontier control. The Stanegate frontier thus created, developed further, and consolidated during the late first and early second century AD and helped crystallise Roman tactics and military expectations in the area.

The function of the road and its forts changed when Hadrian’s Wall was constructed to the north, and their support roles were, initially at least, enhanced. The later history of the road and its forts and their relationship with the Wall is less well understood, although, overall, their strategic functions declined as the new frontier line was confirmed.

Therefore!

Stanegate is built from Corstopitum (Corbridge) to Luguvalium (Carlisle) 13 miles constructed between 77 to 85 AD as a predates Hadrian’s Wall, but it’s not like most Roman Roads as it’s not straight and follows the contours of the landscape. Moreover, when the Romans withdrew from Scotland in 105 AD (Hadrian’s wall was built in 122 AD) it was used as a frontier line.

But is it true?

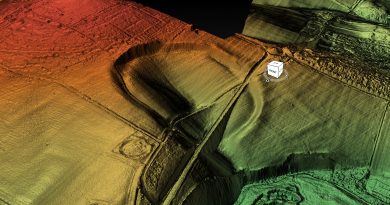

Let’s look at the suggested route and find out using LiDAR if it is remotely true?

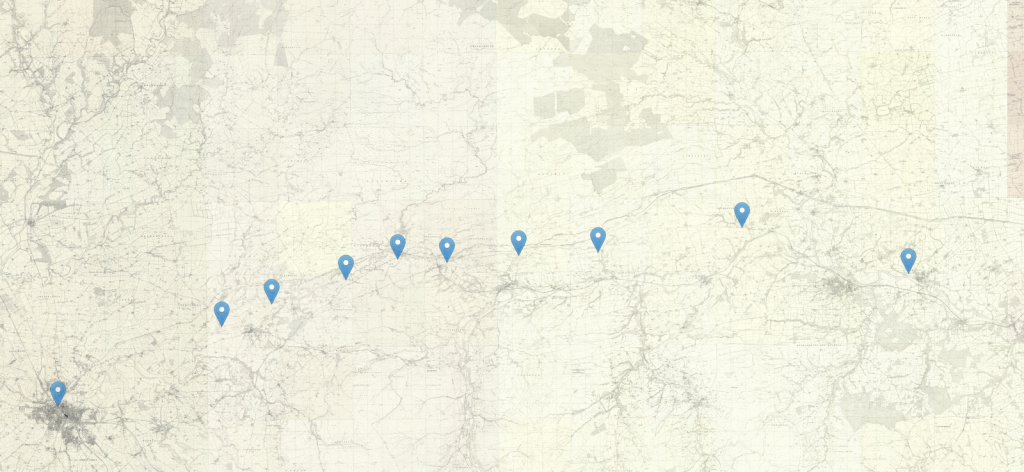

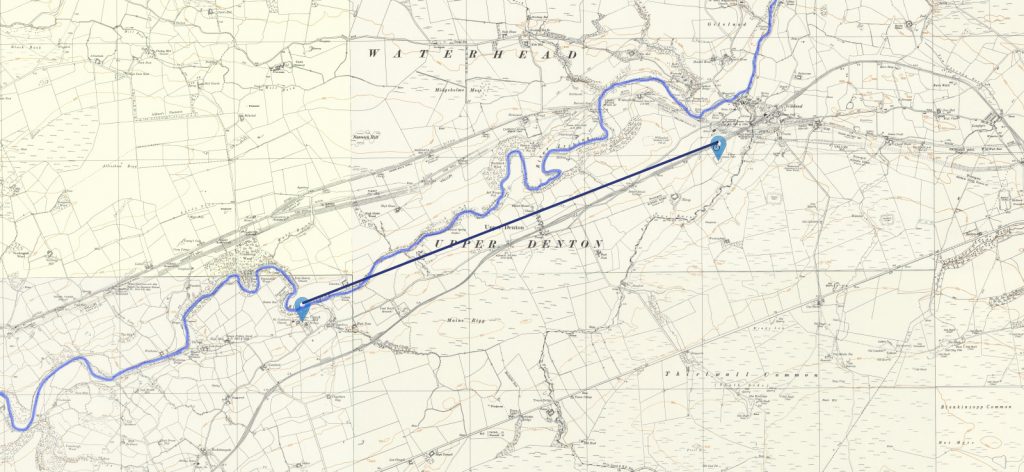

For Ease’s purpose, we will go from West to East for reasons that will become obvious at the end of the case study.

Route

The Stanegate began in the east at Corstopitum, where the critical road, Dere Street headed towards Scotland. West of Corstopitum, the Stanegate crossed the Cor Burn, and then followed the north bank of the Tyne until it reached the North Tyne near the village of Wall. A Roman bridge must have taken the road across the North Tyne, from where it headed west past the present village of Fourstones to Newbrough, where the first fort is situated, 7 miles (12.1 km) from Corbridge, and 6 miles (9.7 km) from Vindolanda. It is a small fort occupying less than an acre and is in the graveyard of Newbrough church, which stands alone to the west of the village.

From Newbrough, the Stanegate proceeds west, parallel to the South Tyne, until it meets the next major fort, at Vindolanda (Chesterholm). From Vindolanda the Stanegate crosses the route of the present-day Military Road and passes just south of the minor fort of Haltwhistle Burn. From Haltwhistle Burn, the Stanegate continues west away from the course of the South Tyne and passes the major fort of Magnis (Carvoran), 6 miles (10.5 km) from Vindolanda and 20 miles (32 km) from Corstopitum. The road is joined by the Maiden Way coming from Epiacum (Whitley Castle) to the south.

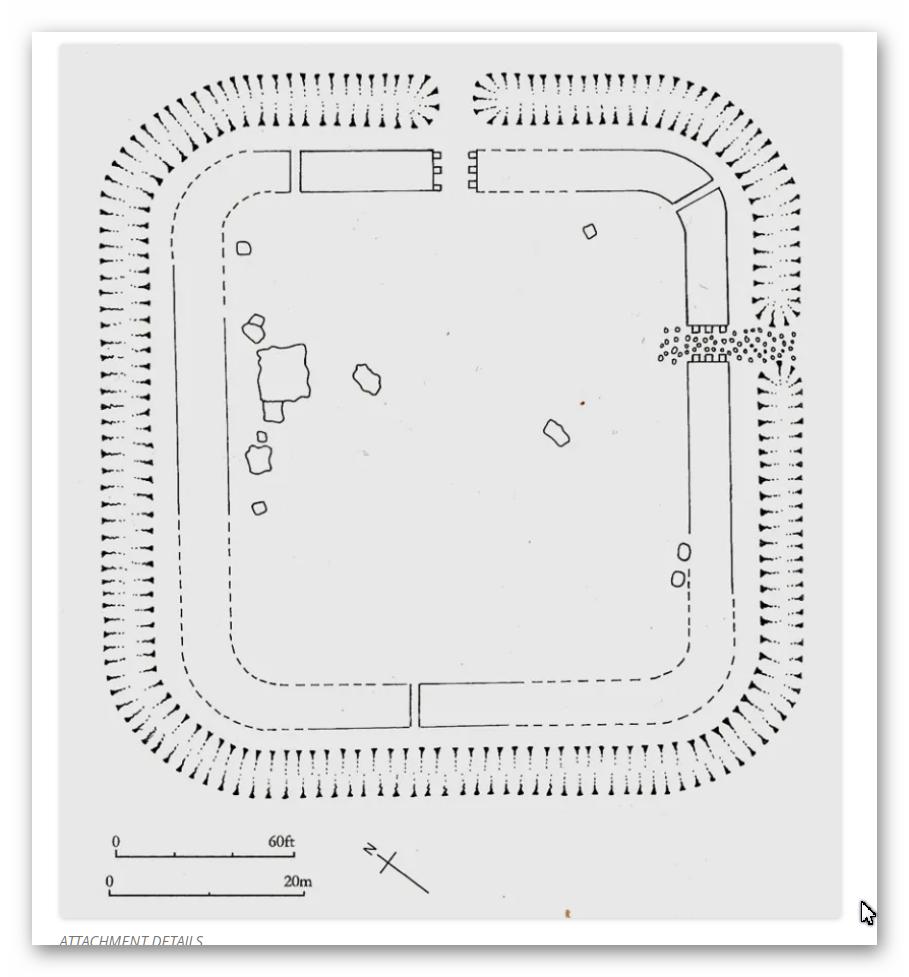

From Magnis, the road turns towards the southwest to follow the course of the River Irthing, passing the minor fort of Throp, and arriving at the major fort of Nether Denton, 4 miles (7.2 km) from Magnis and 24 miles (39.4 km) from Corstopitum. The fort occupies an area of about 3 acres (12,000 m2).

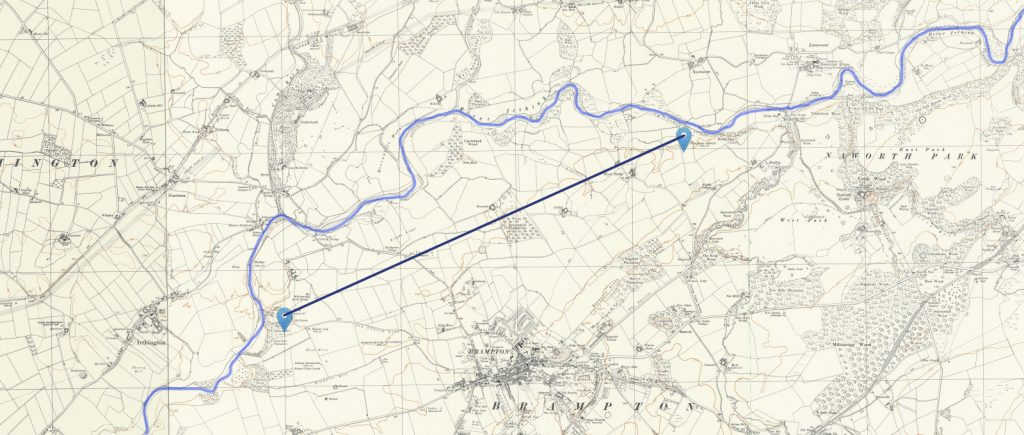

From Nether Denton, the road continues to follow the River Irthing and heads towards present-day Brampton. It passes the minor fort of Castle Hill Boothby and then, 1 mile (1.6 km) west of Brampton, reaches the next major fort, that of Brampton Old Church, 6 miles (9.7 km) from Nether Denton and 30miles (49.1 km) from Corstopitum. The fort is so-called because half of it is buried under Old St Martin’s church and its graveyard.

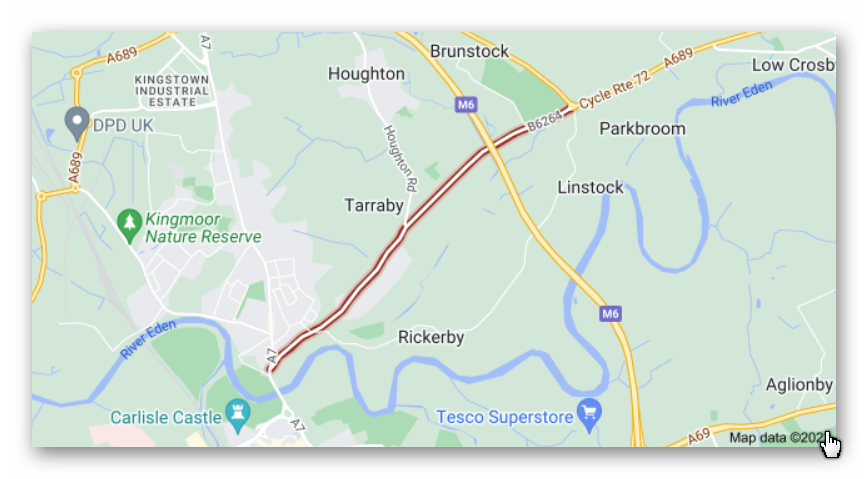

From Brampton Old Church, the road crosses the River Irthing and continues southwest through Irthington and passes through what is now the site of Carlisle Airport, just to the north of the main runway. The curving corner of an associated marching camp can be made out from the air on the south edge of the runway near its western end and seen on Google Earth. The Stanegate then continued through an extensive cutting in High Crosby, where a small fort was postulated based on marching distances but was not yet found.

The Stanegate then crossed the River Eden near the cricket ground[9] in modern Carlisle and eventually reached the fort of Luguvalium (Carlisle) on the site of Carlisle Castle, 7 miles (12.1 km) from Brampton Old Church and 38 miles (61 km) from Corstopitum. It has been suggested that the road may have carried on west for a further 4 miles (7.2 km) to the Roman fort at Kirkbride overlooking Moricambe Bay, an inlet of the Solway Firth. A large camp of 5 acres (20,000 m2) was found there but the evidence for a road is insufficient.

It has also been suggested that the Stanegate may have run eastwards from Corstopitum towards Pons Aelius, present-day Newcastle upon Tyne, and possibly linking to Washing Wells Roman Fort in Whickham, but no evidence has yet been found to support this.

The first thing you notice is that they are not in a line and the gaps (for a 6.5mile marching gap) is inconstant.

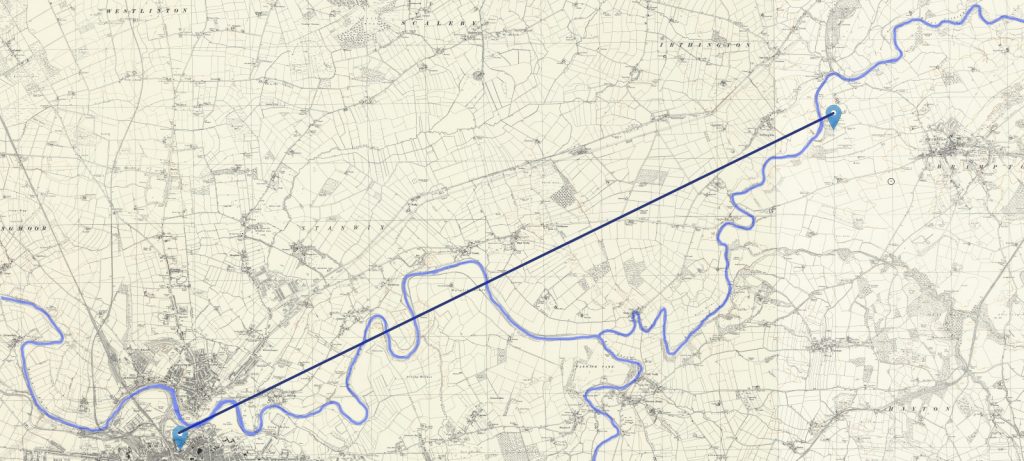

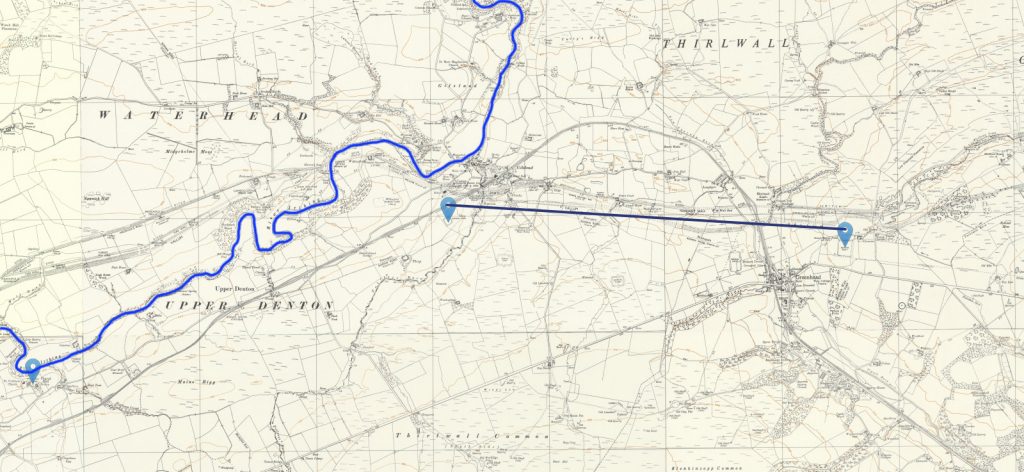

Carlisle to Brampton Section (7.8 miles/12.5 km – Direct)

The most obvious route from Carlisle Castle (Luguvalium Roman Fort) is the B4245, which may have been originally the ‘Stanegate road’ which heads for Brampton Old Church Roman Fort via Irthington.

One would imagine that you would stay on this road until you get to Brampton – but the OS maps show that you veer off at High Crosby?

The problem is that (although the road has been spotted on Google Earth – LiDAR shows absolutely nothing?

The line (which goes through Carlisle airport – shows little to no road and abruptly ends at a massive riven and the river Irthing. The fort has no direct road access (even if you continued on the B4245 and not turned off) until you reach Brampton, and then it’s a windy 1.5 mile / 2.4 km road (old church road). So to supply this station, you will need a boat and hence its position by the river.

Brampton To Boothby Fortlet (2.4 miles / 3.8 km)

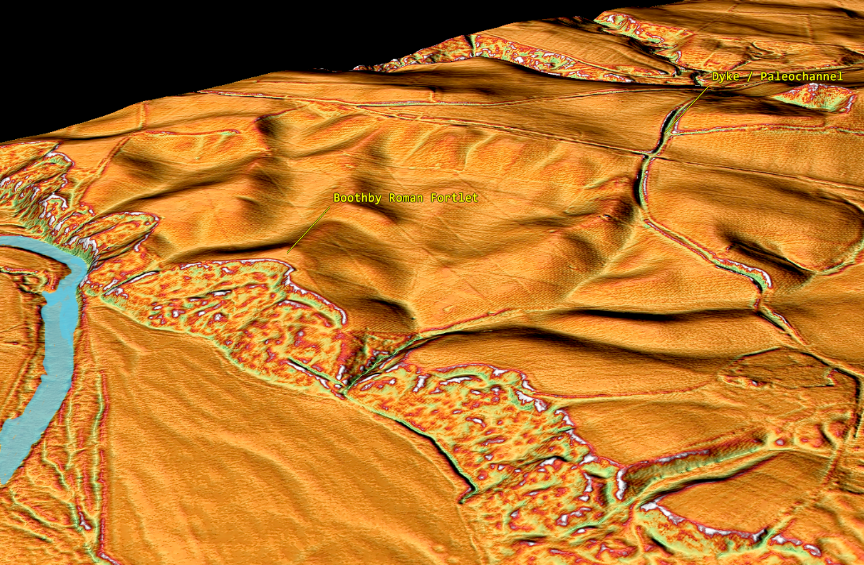

There is no road on the OS map that connect the two forts or any scheduled monument. There is nothing on the LiDAR map, and Boothby fort may appear on the OS and scheduled monuments listing – but on LiDAR, there is absolutely nothing or any road connection?

If Boothby slips into the old riverbed – the river must have been much more prominent in the past than today?

This would question if the site was Roman or Prehistoric? Interestingly, we have identified possible Dyke/Paleochannel in this area. Is it possible that it was another Dyke/Paleochannel that was identified in 1947 by air photography as a side of the Roman fort and is is the Dyke that was partially excavated?

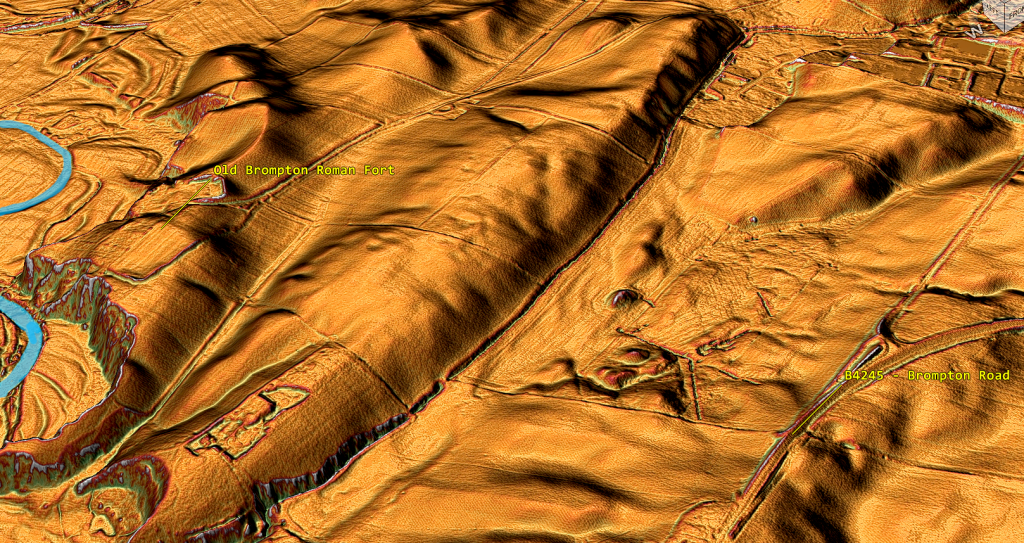

If we return to our LiDAR map of the area and flood it with a higher water table (10m over the current river level), we not only see why Boothby slid into the water (if it was a Roman fort) but was also see Old Brampton roman fort was so isolated with no adjoining roads – it’s on an island?

So what’s going on here?

We have failed to find Stanegate road (if the OS map is correct), and neither of the Roman forts has any road connection to the Stanegate – even if the current Old Brampton Road is the real Stanegate?

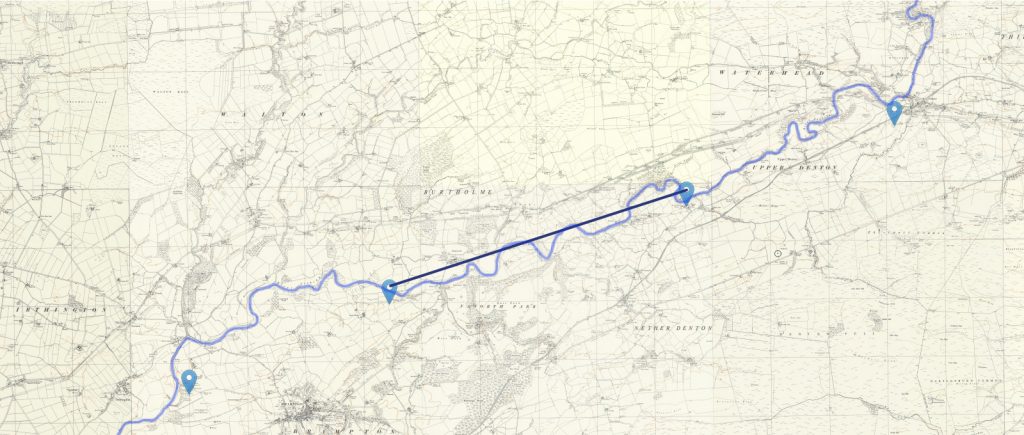

Boothby to Nether Denton Roman Fort (3.4 miles / 5.4 km)

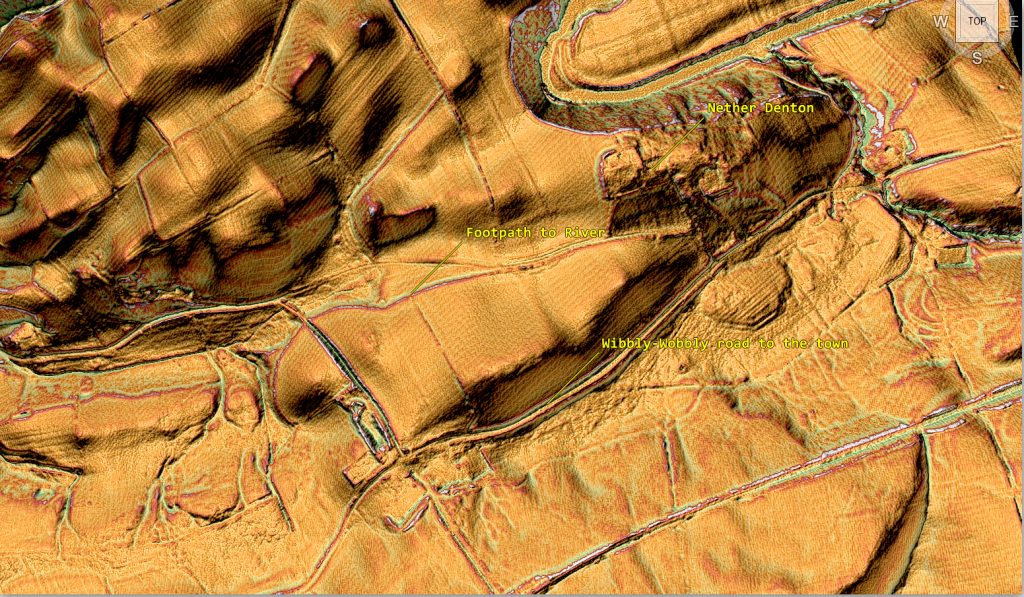

Again there is no road (modern or old that connects the Nether Denton Fort to Boothby) – the only connection is the river, and it is this river that archaeologists are now suggesting was the ‘natural’ boundary when the Roman retreated from Scotland in 105AD before Hadrian’s Wall was constructed. (Symonds, 2017). The pathway to the south of the fort stops at the river.

The first 5 Roman forts on the ‘Stanegate road’ are on the river irthing and not connected by a single road!!

So where is Stanegate, and did it ever connect any Roman forts together?

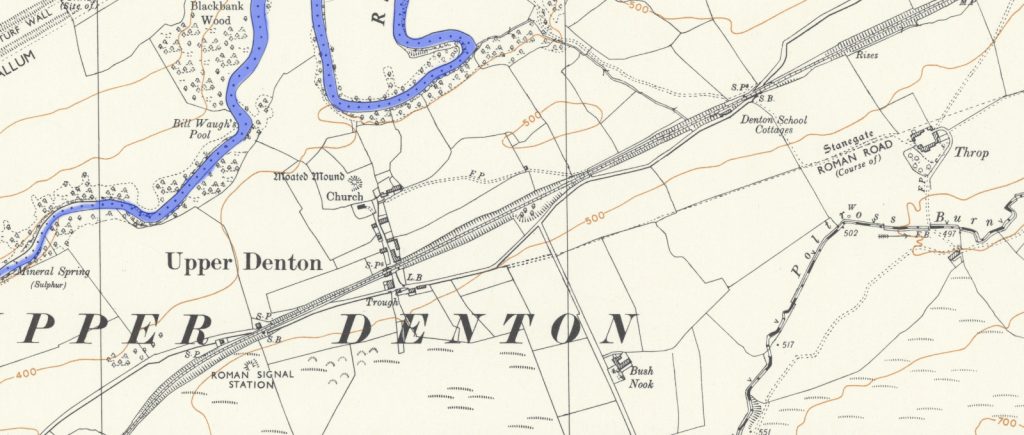

Nether Denton Roman Fort to Throp (2.3 miles / 3.8 km)

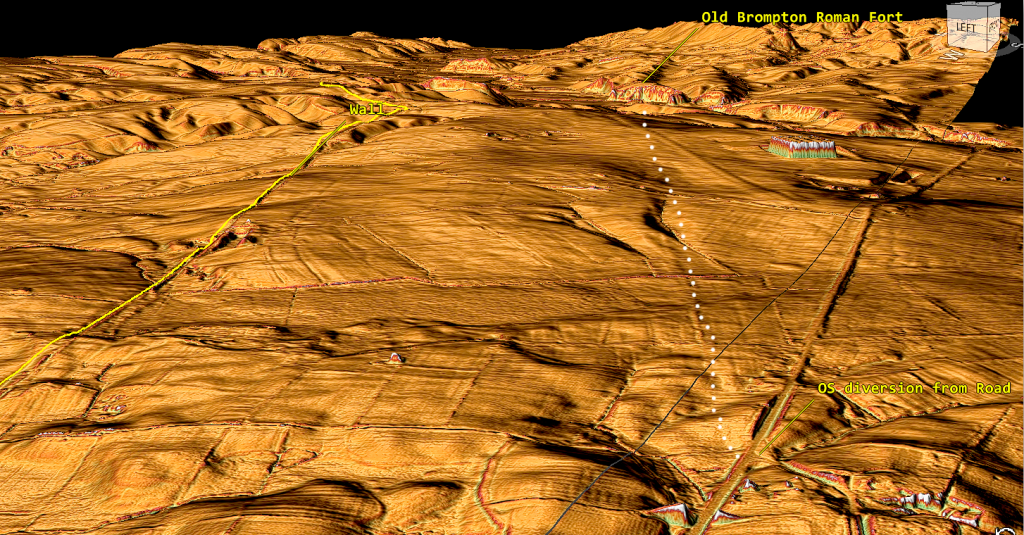

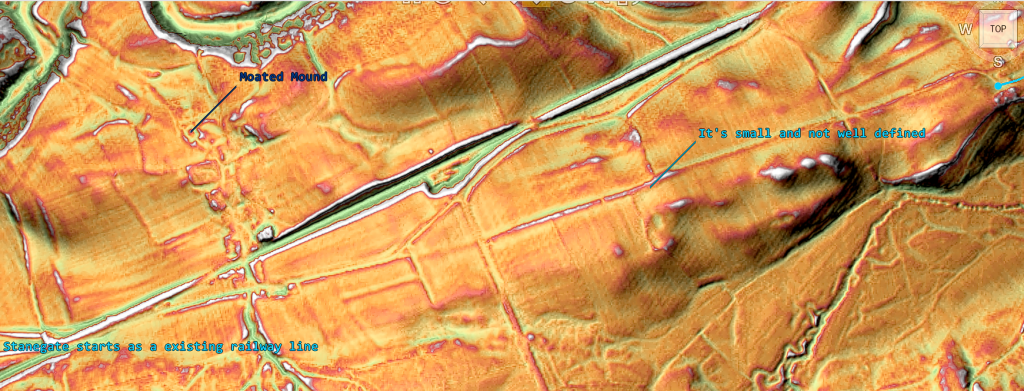

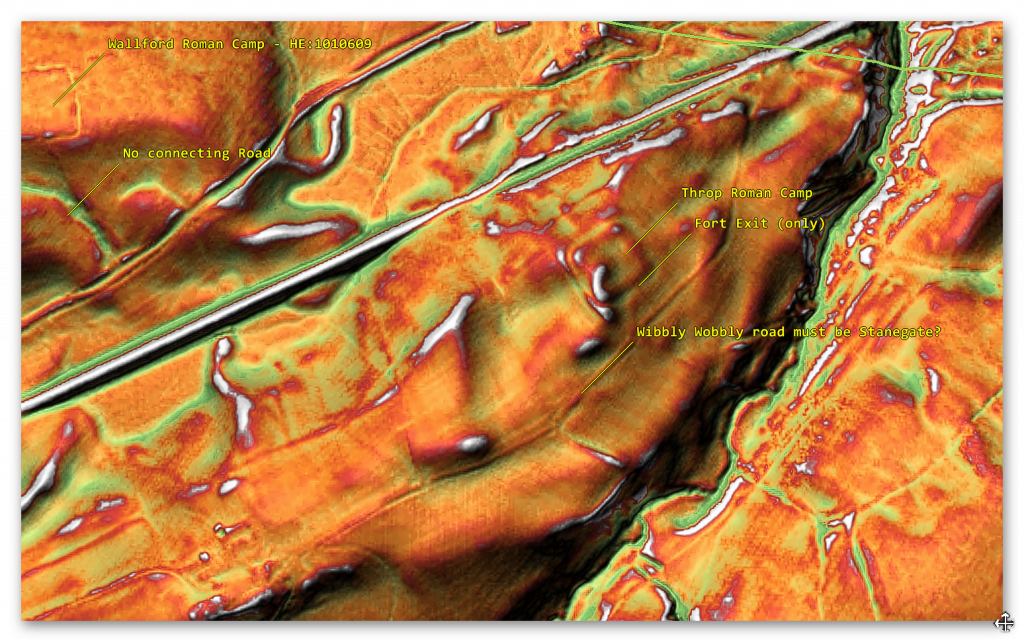

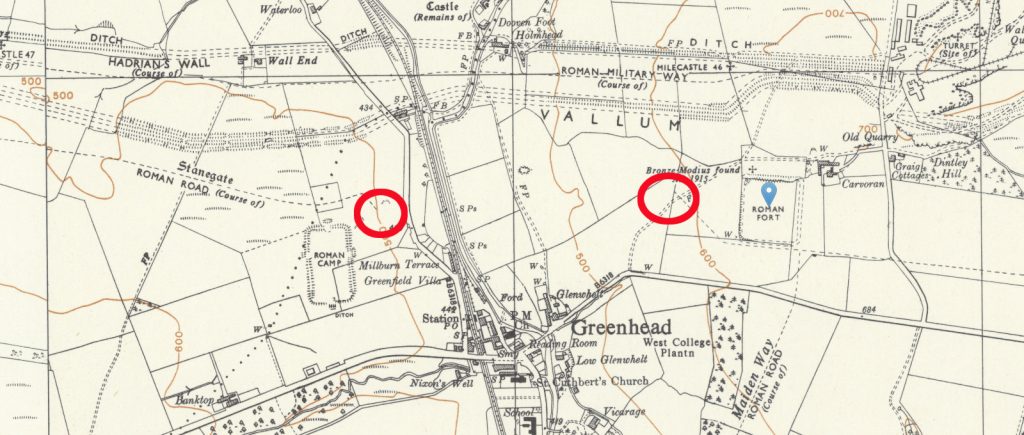

The first signs of the Road called Stanegate on the OS map, which makes any sense comes as we moved towards the fourth fort, ‘Thorpe’- further down the river.

This road is not well defined in the landscape, with a single ditch (8m) on the North side rather than two ditches on either side. The road itself is 9m wide then halfing to 4m wide.

According to the archaeologists, Throp Fort/camp’s exit is obvious (South East).

If Throp Fort does indeed join Stanegate – then the road is very ‘wibbly wobbly’ in construction and veers North East past Throp Fort and into a riven where it disappears by the Vallum (green line), which also seems to be missing??

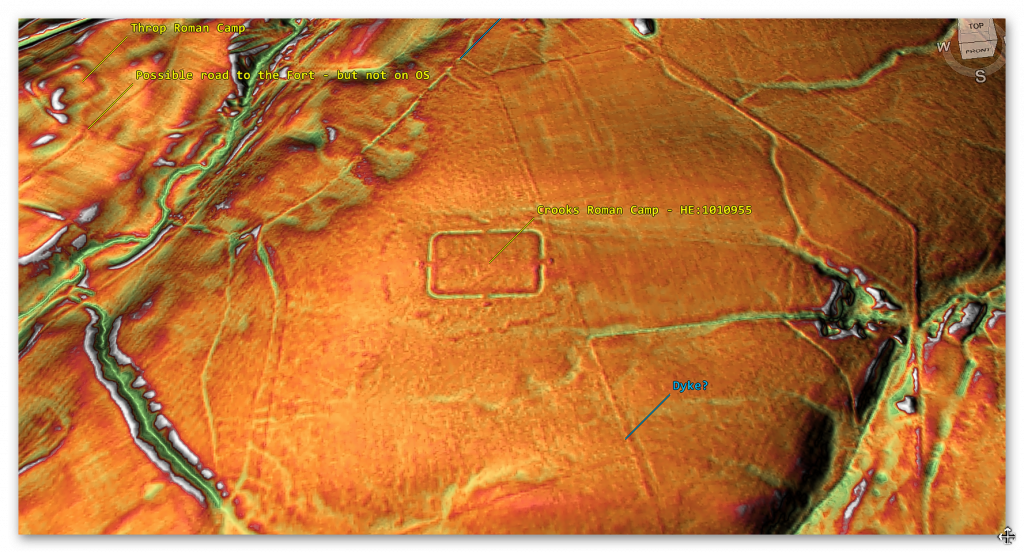

We also see other Roman camps like Wallford (like the last four Roman sites we have studied) that are next to the River Irthing – but again not the road to Stanegate – although only a few hundred metres from the site according the OS maps? Moreover, there are more substantial (sized) than Throp; Wallford (626m to the NW) and Crooks (600m to the SE) therefore has it been misidentified as one of these critical sites of defence??

Consequently, if it was a fall-back position, and using the River as a boarder marker – it was too far away from the River to be effective and so Wallford (which is on the water would be the preferered fort?

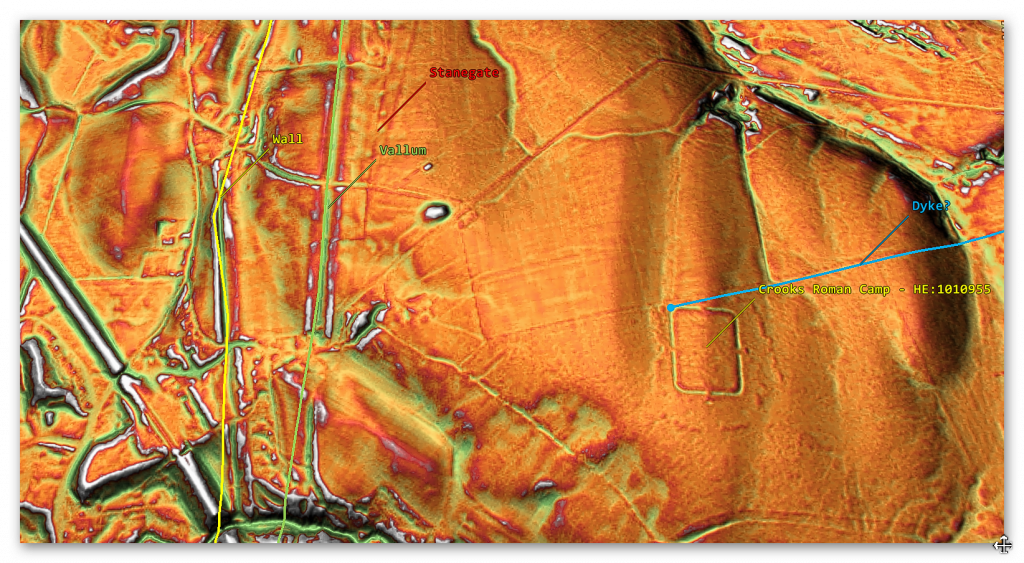

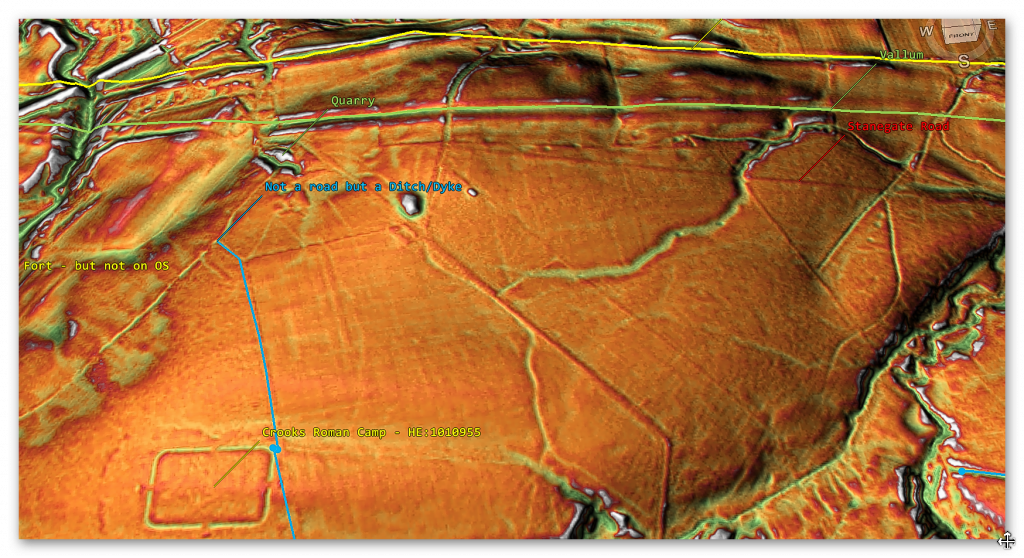

Trop to Carvoran (2.1 miles/3.4 km)

A road that goes to Carvoran from Throp Roman Fort presides, seems to start in the region of the quarry – there is no sign of any road in or coming out of the riven. The Vallum seems to do the same – which is an indication of the probable water levels or terrain of this area.

The other Roman fort you would expect to connect to any existing road – Crooks Camp seems to be connected by what looks like a Dyke rather than a Road as it has a double bank on each side of the straight track – which starts in a river valley and ends in the same river valley as Stanegate starts?

But a clear connection to the Fort is not conclusive as the road/dyke is at a strange angle, and one would imagine that if the trackway existed at the time of construction – the fort would be built to the exact alignment rather than aligning with the two river valleys in the area?

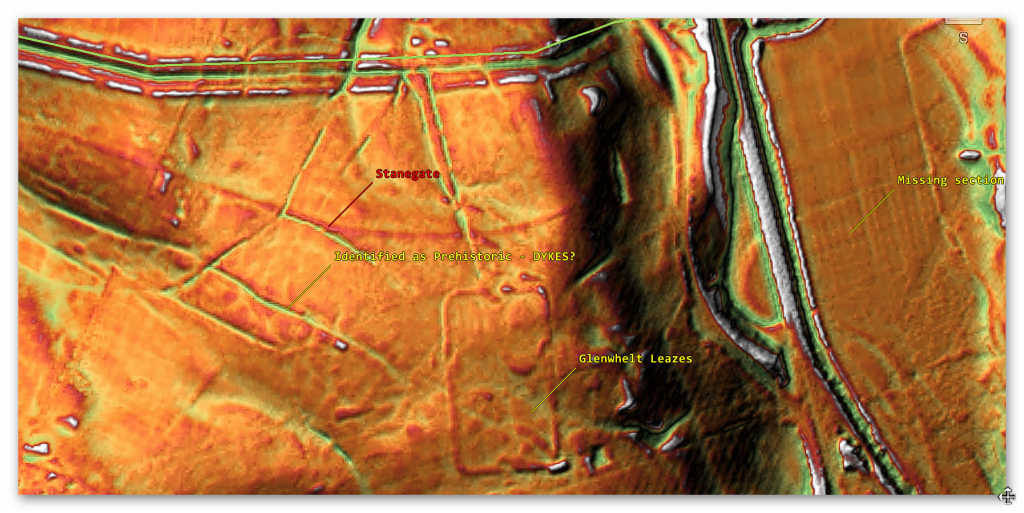

Further down the observable road, we find a Roman Fort that seems to connect to this section of Stanegate – called Glenwhelt Leases.

There seems to be a direct connection to Stanegate via a sunken path? This path continues to the Vallum, passing Stanegate – an Historic England Report ‘Haltwhistle Golf Course, Greenhead Carlisle; Glenwhelt Leazes Temporary Camp: Aerial Assessment by Cara Pearce – suggest that the ditches to the WEST of the site are prehistoric in origin (which look like the same size and shape as the ditch going North?

There is no evidence of Stangate or the road going down the slope to the river or crossing this riven (need a bridge?), and OS maps show it disappears and then reappearing just before Carvoran camp.

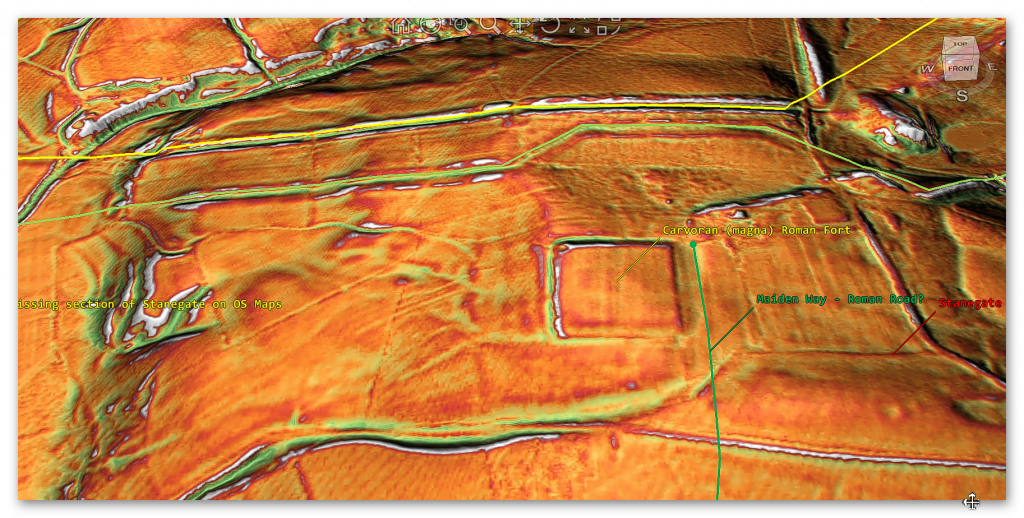

On the other side of the riven is Carvoran Roman Fort. The OS map suggest a SE Stanegate meet the Southern aspect of the Fort and then continued East in parallel to the forts wall until it meets another Roman road called Maiden Way – sadly LiDAR suggest that this is pure speculation!!

The interesting aspects of Carvoran (somethings known as ‘Magna’ is that it does not connect to Stanegate or Maiden Way?? The only raise walkway is in the NW of the camp and links to the Vallum (again) – as we will see in other case studies, the Vallum (spoiler alert!!) was also used as a roadway

Form the LiDAR map, Stanegate appears from out of the riven, and present roadway sunk into the ground (so could be another Dyke) whose bank was used as a road, and the Stanegate veered off this prehistoric route?

Carvoran (Magna) to Haltwhistle (3.1 miles / 5km)

This is the first stretch of Stanegate that actually is complete and connects two of the supposed defensive forts made for the Stanegate together!!

On this road to Haltwhistle, we notice that Stanegate changes character on several occasions.

At the start of the road in this section, it is 4m wide with no gutter on each side – but as we reported earlier, “Where it left the base of Corstopitum, the Stanegate was 22 feet (6.7 m) wide with covered stone gutters and a foundation of 6-inch (150 mm) cobbles with 10 inches (250 mm) of gravel on top.” So we are looking at a 7m road that fits the classic description.

So, this section is nearly half the expected size?

A few hundred metres East of this point, the Stanegate turns into a 24m wide road with an 8m central road way and 8m ditches on both sides – before disappearing into quarries. And these quarries are commonplace on this road – which we will look at more in the essay’s conclusion. Then Stanegate emerges into a broken, dysfunctional construction of no obvious nature.

And so when it crosses a modern suspected Roman Road, we see no kind of intersection and barely a trace of Stanegate.

Stonegate returns to its single track just before it reaches Haltwhistle Fort and once again turns into a ditch with two banks, then disappear down ‘Haltwhistle Burn’ returning as a ditch with two banks (20m wide) or could be judged as a Bank with two ditches 23m wide with ditches the same size as the Fort.

The fort itself is also interesting as the design is a fort within a fort – which archaeologists have suggested it was designed this way as:

“Nevertheless, it seems convincing and matches the presence of storage facilities in some larger road fortlets elsewhere, such as Castleshaw (Bidwell and Hodgson Reference Bidwell and Hodgson2009, 73). The articulation of the Stanegate fortlet gates makes sense to allow traffic loading or offloading goods to circulate easily through the installation. Building a measure to aid traffic flow into the design implies that this was a fundamental concern, suggesting a logistical role for the fortlets, rather than frontier control.”

This idea of storage we again will come back to in the conclusion.

Haltwhistle to Vindolanda (3.4 miles – 5.5)

The Stanegate Road to Vinddolanda is of great interest as it goes past a vast number of Quarries and Forts, including Haltwhistle Tep camps 2 & 3, which again have no road connection to Stanegate Milestone House, Seatsides 1 & 2 Temp Camp, bean Burn 1 & 2 and a massive 15 Quarries.

One of these Milestone House can’t be a defensive fort as it is too large and in the eastern side unprotected – moreover, it’s covered in Quarries, and EH reports kilns. So this was a protected industrial area, and it seems that the other Temp camps were probably storage areas for their mining operations? Interestingly as the boundary of the fort goes over the existing B-road – we can concluded that at the time of construction (of the fort) the Stanegate was the only road, but the fort boundary falls short of the road on both East and West sides?

When we finally reach Vindolanda, the OS maps suggest that Stanegae separates from the existing road and by passes (no doubt with the view of it connecting to the fort) then moves across the valley to move NE to the next fort.

Sadly, this is not the case, and the fort doesn’t seem to have any connection to either Stanegate or the current road.

The most up to date map (from the new Charitable trust) shows the road coming out NW and joining the new road (no sign of Stanegate on this map?)

Vindolanda to Newbrough (6.2 miles / 10 km)

Stanegate becomes an existing road at an interesting junction. The OS map shows Stanegate coming out of the riven of Vindolanda but is not on the LiDAR map

Stanegate seems to come out of a steep gradient from the raven (like a Dyke) and head towards a quarry. Then it starts again on the other side of the quarry ‘under’ the existing B-road.

This B-road has had Roman milestone found (in the 19th century) by the wayside and travels all the way to Newbrough, passing numerous quarries and two other Roman temp forts again without clear road connections.

The ‘experts’ are confused by the site as:

“Newbrough Roman Fort was 195ft north-south and190ft east-west. This is about 0.75 acres sufficient to house two centuries, say 160 infantry. The stone walls were surrounded by a ditch 15ft wide and 5ft deep, 16ft from the walls, which were 4ft wide. It was identified as the 4th century by coins, pottery and construction. Why it was built here close to Hadrian’s Wall is a mystery. It was only excavated once in 1930.

At the beginning of the 2nd century, the Stanegate had become the defacto frontier just before Hadrian’s Wall was built.

The location indicates that should have been an earlier fort here at the beginning of the 2nd century, but nothing was found at that time.”

Is it as if there was a huge gap in the Stanegate Road theory and needs something to fill it?

Newbrough to Corbridge (7.4 Miles / 11.8 km)

Once Stanegate leaves Newbrough town on the existing B-road, the OS maps show it veers off NE into nowhere. This seems to be because they have found a piece of ‘Roman Road’ by another quarry (about a mile from the turn-off) and arachaeologisyt have imagined it to be Stanegate – the LiDAR map shows that this route does not exist in reality but only this tiny (220m) roadway.

Stanegate disappears going towards the River Tyne – in theory it is supposed to cross the river (via a bridge) and then head south to Corbridge.

We see a wibbly-wobbly ditch and bank – which is probably a Dyke – certainly not a bridge and no signs of a road down the bank of the Tyne unless the railway built it on top of Stanegate – but why would your follow the river doubling the mileage when you build a road direct accros land,and the railway ends only halfway at acob not Corbridge!

Moreover, if we attempt to trace this road from Corbridge to where we left it outside Newbrough, we find that the OS map shows no trace (apart from a Roman road heading for the Roman baths that disappear into yet another Burn?

In all honestly, this is such a loose connection – its beyond comprehension and the reason we started our investigation from the West to East as the suggestion:

“The Stanegate began in the east at Corstopitum, where the important road, Dere Street headed towards Scotland. West of Corstopitum, the Stanegate crossed the Cor Burn, and then followed the north bank of the Tyne until it reached the North Tyne near the village of Wall. A Roman bridge must have taken the road across the North Tyne, from where it headed west past the present village of Fourstones to Newbrough.”

All we see fro the last visible aspect of the Stanegate is a wibbly-wobbly trackway which looks more like a Paleochannel/Dyde rather than a Roman Road, which doesn’t match the OS Map route. Moreover, there is no sign of a ‘foundation’ for a bridge (which had to be really large?) or the Stanegate going south to Corbridge.

Conclusion

Our investigation found that there is very little to no evidence (20%) of the ‘Stanegate Roman Road’, which (according to the current theory proposed by English Heritage) ‘consolidated as a frontier’ during the late first and early second century AD and helped crystallise Roman tactics and military expectations in the area.

Stanegate Road (when not part of an existing B-road system) is inconsistent in width and structure -moving from bank track to road with two ditches on each side to a ditch with two banks on each side, that is far from straight and usually starts and ends in ravens.

The majority of the Forts and the Stanegate are not found to connect (with intersecting sub-roads) on only two occasions, and the rest show no form of connection at all. Moreover, later ‘temporary’ camps also did not connect with the road – which questions whether (a defence line) was its purpose.

Moreover, this would then question the ‘myth’ of using the Stanegate as a ‘boundary’ for the withdrawal of troops from Scotland in the first century AD is correct. And whether the River Tyne (which most of these Forts sit upon) was used as a more practical and effective boundary/defence?

This ‘myth buster’ will not surprise many in academia as it has been ‘hinted’ at for some time (but not acted upon it by updating the literature) as we see from Symonds et al.

“The question of whether a road even existed when the fortlets were founded is by default an existential one for the notion that they provided highway protection. But even if the metalled road does post-date the fortlets, a reasonably robust thoroughfare of some form must have existed from at least the mid AD 80s to service Vindolanda. The question, then, is not whether there was a road, but whether it was metalled when the fortlets were founded.” Symonds, M. (2017). Hadrian’s Wall. In Protecting the Roman Empire: Fortlets, Frontiers, and the Quest for Post-Conquest Security (pp. 95-132)

Moreover, even if Stanegate was not built as suggested, it exists in parts, and it looks prehistoric (by design) as it has a heavy reliance on ravens that start and end sections of the Stanegate sections; its sunken structure in parts is unfamiliar to traditional Roman Road design.

So, are we seeing the use of prehistoric Dykes (linear earthwork) banks being utilised for a new purpose?

As we have shown, there are many ‘quarry sites’ along the Stanegate Road and an increased number of ‘temporary’ forts, some of which have these quarries inside. Therefore, have archaeologists missed the point of not only the ‘temporary’ forts but the purpose for the roads use and, consequently, why Hadrian’s Wall was built?

When the Roman Empire decides to invade any country (contrary to the traditional myth), it was for the possession of more incredible wealth. Britain was a wealthy (iron Age) island, perfect for conquestas it had rich commodities such as gold, silver, tin, lead, and wheat and slaves. Some of this mineral trading wealth is found in the quarries that surround this area and has been exploited since the dawn of trading (prehistoric times).

This may explain why so many unscheduled Dykes are found in this area and why so many of them start/terminate within the quarries. Romans are the best adapters in history when it comes to the assimilation of foreign assets, engineering and cultures – therefore, would it not have been prudent to take the existing infrastructure of Dykes and adapt them to make roads rather than starting from scratch? (we will see this in detail when we examine the Roman Vallum).

These quarries needed a workforce to extract the minerals and therefore housing, feeding facilities to function, and storing the precious quarried materials. We have seen how this has been done in history by lightly guarded fortifications (places with wooden walls and armed guards), and is this what we see alone on Stanegate Road with the ‘temporary’ fort camps?

Eventually, these ‘warehouses’ would have been a target for raiding and robbery – so would it not make sense to eventually build a more substantial defence against robbers (non-enslaved picts of Scotland?) and is this the real reason that the Romans built Hadrian’s wall and why it was moved just after 40 years to incorporate the quarries that are currently north of the Wall?

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

To understand why rivers were larger in the past we have video with all the relevant information.