Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Southern Circle Revisited: Why It Was Never a “Great House”

- 3 The Ditch That Isn’t a Henge

- 4 Introducing the North Circle: The Forgotten Half of the System

- 5 Reading the Post-Hole Structure Correctly

- 6 Fish Traps, Weirs, and Walkways: A Structural Match

- 7 Hydrology and the Avon Connection

- 8 One System, Not Two Monuments

- 9 Provisioning, Not Symbolism: Fish, Cattle, and Aggregation

- 10 Woodhenge Reconsidered: Why a Real Timber Monument Was Built

- 11 Why the Site Is There: Woodhenge as Beacon, Durrington Walls as Harbour

- 12 Conclusion: A Coastal Logic Inland

- 13 Podcast

- 14 Author’s Biography

- 15 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 16 Further Reading

- 17 Other Blogs

Introduction

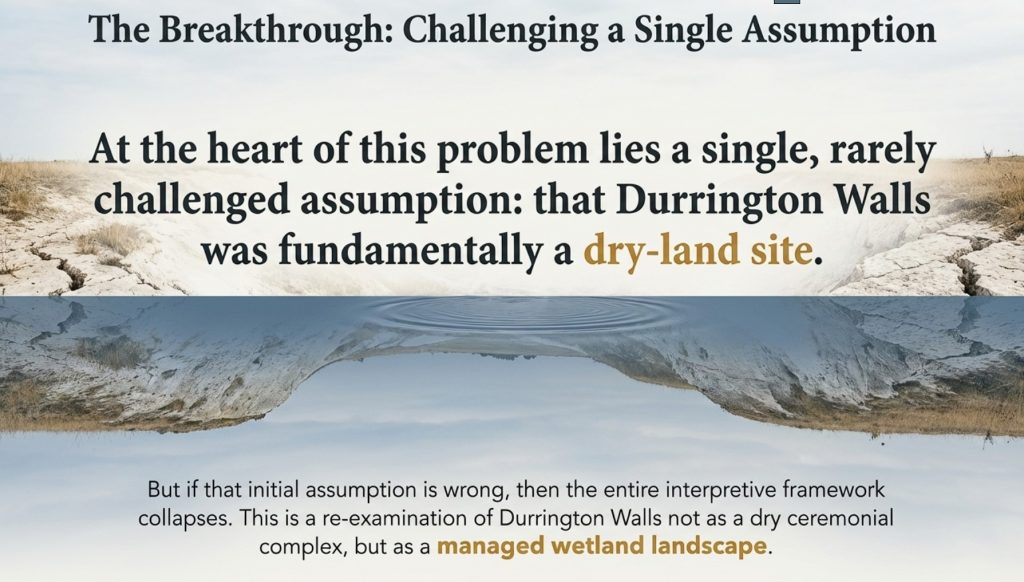

Durrington Walls has long been treated as a problem site. Despite decades of excavation, reinterpretation, and popular retelling, it has never settled comfortably into any single explanatory model. It is alternately described as a village, a ritual aggregation centre, a ceremonial counterpart to Stonehenge, or a symbolic landscape without a clear economic function. Each interpretation resolves one difficulty only by creating several others. The result is a site that is endlessly described, but never fully explained.

At the heart of this problem lies a single, rarely challenged assumption: that Durrington Walls was fundamentally a dry-land site.

Once this assumption is adopted, everything else follows automatically. Timber circles must be buildings. Ditches must be boundaries. Irregular features must be symbolic, incomplete, or poorly preserved. Water becomes incidental, a backdrop rather than an organising force. The site is then interpreted through analogy with later prehistoric monuments built on stable ground in fundamentally different environmental conditions.

But if that initial assumption is wrong, then the entire interpretive framework collapses.

This essay re-examines Durrington Walls not as a dry ceremonial complex, but as a managed wetland landscape, operating within a Mesolithic or early Neolithic hydrological regime characterised by elevated groundwater, seasonal flooding, and an expanded River Avon system. When water is treated as an active variable rather than an inconvenience, features that once appeared anomalous begin to behave coherently. Structures that resisted architectural explanation begin to make functional sense.

Crucially, this reassessment does not rely on speculation, symbolism, or ethnographic metaphor. It is driven by structure: by the physical geometry of post-holes, the mechanics of timber insertion and removal, the engineering logic of ditches, and the spatial relationships between features. The question throughout is not “what did this mean?” but “what does this do?”

Previous discussions have already demonstrated that the Southern Circle at Durrington Walls does not conform to the construction logic of a domestic “great house.” Its post-holes show evidence of driven piles rather than excavated sockets, repeated refitment, extraction scars, and maintenance over time—behaviour entirely inconsistent with a single-phase roofed structure, but entirely consistent with a load-bearing platform operating in wet or unstable ground. That argument will be summarised here, not repeated in full.

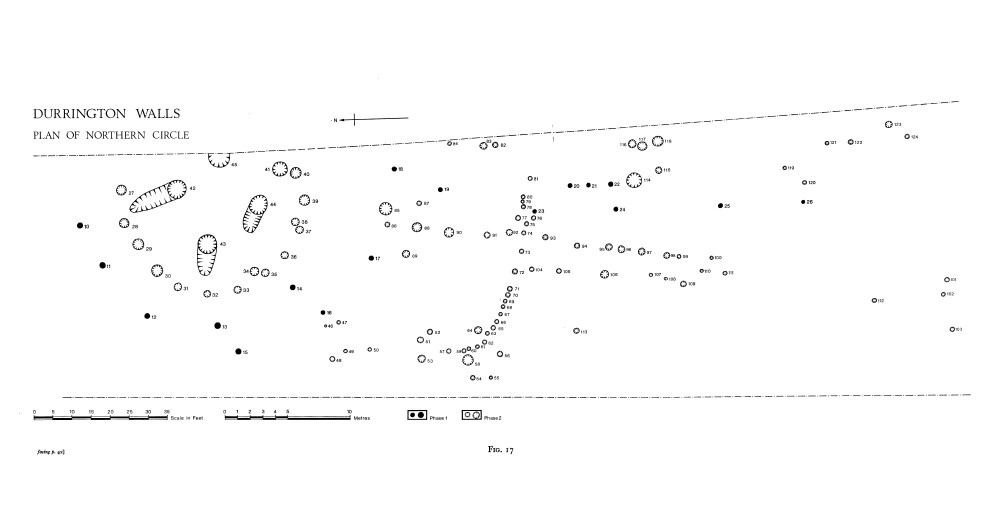

What has received far less attention, however, is the Northern Circle.

The North Circle has always been awkward for orthodox interpretations. It is irregular, incomplete, and structurally incoherent if treated as architecture. It lacks symmetry, closure, and any plausible roof logic. As a result, it has often been marginalised in discussion, treated as a secondary or failed monument, or folded into vague ceremonial narratives that demand little mechanical explanation.

This essay takes a different approach.

Instead of asking why the North Circle fails to resemble a building, it asks whether it was ever intended to be one.

When the North Circle post-hole pattern is examined without architectural preconceptions, a very different structure emerges. The arrangement is directional rather than radial. Post density varies by position rather than by ritual importance. Open-ended alignments replace enclosed rings. Linear elements appear that make no sense as walls, but perfect sense as access routes. In plan, the structure resembles neither a house nor a monument, but a capture and control system.

Specifically, it resembles a stake-built fish trap or weir, integrated into a seasonally flooded landscape and connected—directly or indirectly—to the Avon system.

This proposal is not based solely on analogy. Fish traps across riverine and wetland environments worldwide share a remarkably consistent structural logic: converging stake lines, funnel geometries, selective reinforcement, open ends, and maintenance walkways. These traits recur because they work. When these same traits appear at Durrington, they deserve to be evaluated functionally rather than dismissed symbolically.

The argument developed in the sections that follow is therefore straightforward, but far-reaching. Durrington Walls was not a village decorated with monuments. It was a working landscape, engineered to manage water, movement, and resources. The Southern Circle and Northern Circle were not paired symbols, but paired components within a single operational system: one concerned with capture and provisioning, the other with unloading, staging, and redistribution.

Once this is recognised, Durrington ceases to be enigmatic.

It becomes intelligible.

The Southern Circle Revisited: Why It Was Never a “Great House”

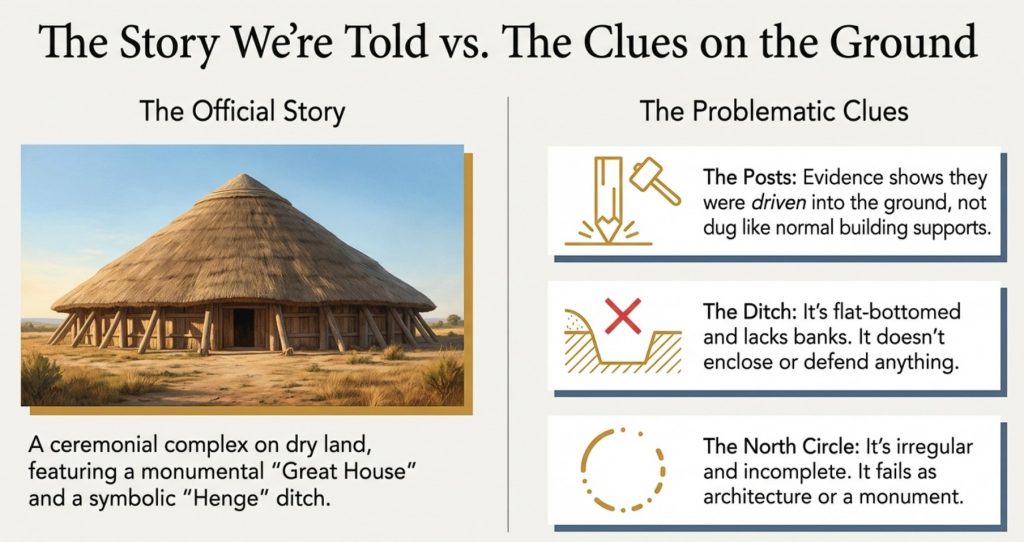

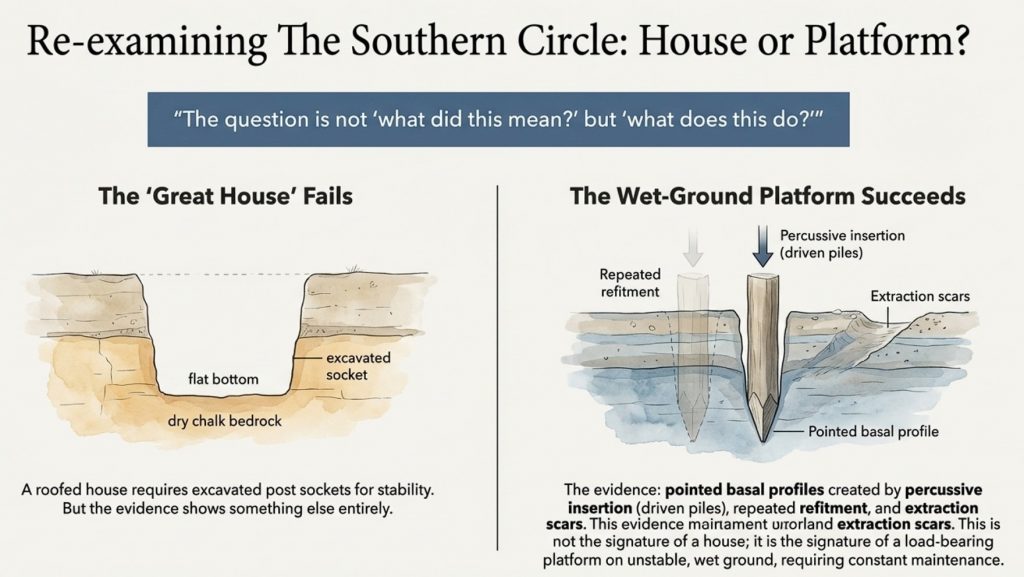

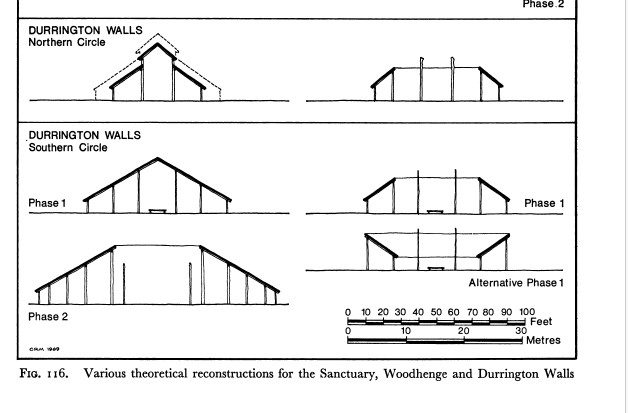

The interpretation of the Southern Circle at Durrington Walls as a monumental timber “great house” has become so familiar that it is rarely interrogated at a mechanical level. The idea is attractive: a vast roofed hall, domestic or ceremonial in nature, forming a symbolic counterpart to Stonehenge. Yet when the excavation evidence is examined in detail—particularly the published section drawings rather than the interpretive summaries—the great house model begins to fail almost immediately.

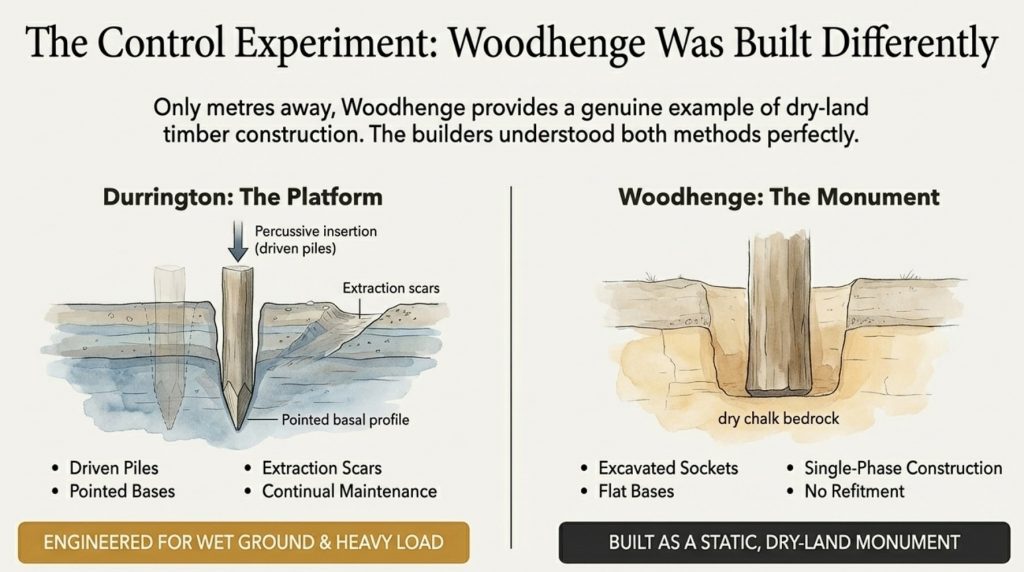

The most revealing comparison lies only a short distance away. Woodhenge provides a genuine example of dry-land timber construction in the same landscape. There, the post-holes behave exactly as expected for excavated sockets: bases are flat or gently scooped, profiles widen with depth, and the construction appears largely single-phase. There is no evidence for repeated refitment, no extraction scars, and no need for structural revision once the building was complete. This is what dry-ground timber architecture looks like.

The Southern Circle shows none of these characteristics.

Instead, a significant proportion of its post-holes display pointed or strongly convergent basal profiles. This is not a minor detail. In chalk geology, a pointed base cannot be created—or preserved—by excavation using antler picks or stone tools. Digging necessarily destroys such geometry almost immediately: chalk fractures, loosens, and collapses under levering action. The only reliable way to create and preserve a pointed basal profile in chalk is through percussive insertion—repeatedly driving a sharpened timber pole vertically into the ground.

In other words, these posts were driven, not dug.

This single observation has far-reaching consequences. Driven posts imply a construction method closer to pile-driving than pit excavation. They imply a concern with vertical load transfer rather than lateral stability. And they imply ground conditions in which excavation was either impractical or unnecessary—conditions consistent with saturated or semi-saturated substrates, not dry stable ground.

The Southern Circle also shows extensive evidence of refitment and maintenance. Many post-holes were re-cut, enlarged, or overlapped by later insertions. Some show multiple phases of intervention, with earlier sockets truncated or partially reused. This behaviour is incompatible with a roofed hall. Large timber buildings are constructed once, used for their lifespan, and then abandoned or dismantled. They are not repeatedly re-engineered at the level of individual load-bearing elements.

Platforms, by contrast, are.

A load-bearing platform operating in wet ground is subject to continual stress. Timber piles rot, shift, or fail below the waterline. Loads change seasonally. Maintenance is not optional; it is a structural necessity. The Southern Circle’s pattern of intervention fits this logic precisely. It behaves like a working structure that requires periodic repair, not like a symbolic or domestic building.

The so-called “ramps” associated with many of the Southern Circle post-holes reinforce this conclusion. These features have traditionally been interpreted as construction aids, used to insert large timbers into excavated pits. Mechanically, this interpretation is weak. A pointed timber pile does not require a ramp to be driven vertically. It does, however, require leverage and access when being removed—especially from wet or compacted ground.

The ramps at Durrington are irregular in orientation, inconsistent in form, and closely associated with refitment episodes. They make little sense as planned construction features. They make perfect sense as extraction scars, created when failing piles were levered out at oblique angles prior to replacement.

Water also resolves several subsidiary problems that have long accompanied the Southern Circle. The relative absence of charcoal, often cited as anomalous for a timber structure, is easily explained in wet conditions, where organic debris is floated away, oxidised, or redeposited elsewhere. The preservation of pointed basal profiles becomes more plausible when chalk fines slump and seal around driven posts in saturated ground. Even the subtlety of the ramps themselves is better explained by soft, infilling sediments than by erosion on dry surfaces.

Finally, the location of the Southern Circle is deeply uncomfortable for a “great house” interpretation. It sits at the head of a coombe, above the River Avon, on chalk geology prone to elevated groundwater, and within a broad flat-bottomed ditch. This is a poor location for a monumental roofed building. It is an excellent location for a pile-supported platform designed to interface with water.

When all of these observations are taken together, the conclusion is difficult to avoid. The Southern Circle at Durrington Walls was not constructed like a house, not maintained like one, and not positioned like one. It behaves instead as a load-bearing, wet-ground-adapted platform, built using driven timber piles and maintained through repeated intervention.

This reclassification is not speculative. It follows directly from the published excavation evidence. And once accepted, it provides the foundation for understanding the rest of the site—particularly the Northern Circle—not as isolated monuments, but as components within a single, coherent system.

The Ditch That Isn’t a Henge

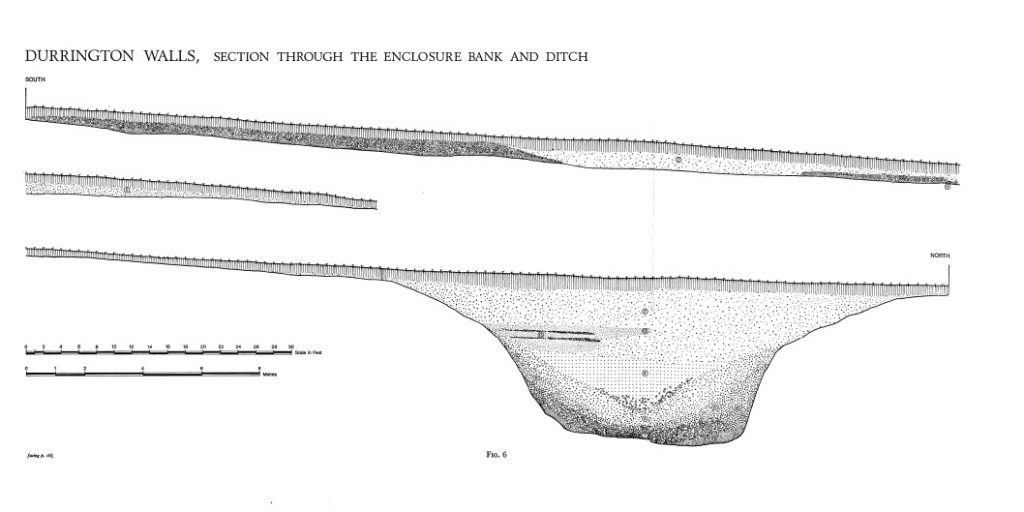

Encircling much of Durrington Walls is a substantial ditch, approximately six metres wide, flat-bottomed, and conspicuously lacking many of the features usually associated with a defensive or symbolic enclosure. For decades, this feature has been described almost reflexively as a “henge ditch.” Yet this label explains little. Instead, it obscures a series of mechanical and spatial problems that have never been satisfactorily resolved.

If the ditch is examined as part of a conventional henge monument, its design is baffling. It has no associated bank, either internal or external. It does not create a visual boundary, nor does it restrict movement in any meaningful way. In places, it terminates abruptly, particularly near the Southern Circle, rather than forming a closed circuit. Its scale is excessive for symbolism alone, yet insufficient for defence. These inconsistencies have been noted repeatedly, but they are usually brushed aside as idiosyncrasies or later disturbances.

The difficulty lies not in the ditch itself, but in the assumption that it must be a boundary.

Boundaries—whether defensive, ritual, or social—require continuity. They are designed to enclose, exclude, or demarcate. They demand banks, palisades, or visual markers that signal a transition from one space to another. The Durrington ditch does none of these things. It is flat-bottomed rather than V-shaped, open rather than enclosed, and discontinuous rather than circuital. As a boundary, it fails on every functional criterion.

As an element of water infrastructure, however, it begins to make sense almost immediately.

Flat-bottomed channels are not arbitrary. They are used where predictable draft matters, where grounding without capsizing is desirable, and where loading and unloading must occur repeatedly. A flat base allows small craft to settle safely as water levels fluctuate. It facilitates the transfer of people, animals, or goods. And crucially, it will enable vessels to wait—either moored or grounded—without blocking movement elsewhere in the system.

In such a context, a bank would be a liability rather than an asset. Banks restrict access, create instability through slumping, and impede lateral movement. The absence of a bank at Durrington is not an omission; it is a design choice.

The ditch also stops where it stops being useful. Near the Southern Circle platform, where water-managed access converges, the ditch terminates rather than looping neatly around the structure. This behaviour is inexplicable in symbolic terms, but entirely logical if the ditch functions as an access basin or secondary channel — infrastructure ends where function ends, not where geometry demands closure.

Further reinforcing this interpretation is the presence of smaller, narrow linear ditches within the enclosure. These features cut across activity areas, vary in depth according to slope, do not enclose anything, and extend beyond the immediate vicinity of the Southern Circle. They are often dismissed as later intrusions, drainage attempts, or poorly understood disturbances. Such labels may account for reuse, but they do not explain origin.

In a dry landscape, these features are indeed awkward. They serve no obvious purpose. In a seasonally flooded chalk landscape, however, they behave exactly as secondary redistribution channels. They guide shallow flows, drain saturated areas, and create controlled pathways for water, people, or small craft moving between functional zones.

The critical point is that none of this infrastructure makes sense unless water was a recurring and significant presence. In permanently dry conditions, the ditch is redundant. The platform is unnecessary. The engineering is absurd. In wet conditions—where wheeled transport fails, livestock must be controlled, and movement across saturated ground is hazardous—water becomes the safest and most efficient route. The ditch, the channels, and the platform together form a coherent system.

This reinterpretation also dissolves the artificial separation between the ditch and the Southern Circle. Traditionally, the ditch is treated as a framing device, a symbolic container for the monument within. Under a functional reading, the relationship is reversed. The ditch exists for the platform, not around it. It facilitates access, movement, and staging at the point where loads are transferred between water and land, or vice versa.

Once the ditch is understood as an access basin rather than a boundary, it becomes clear that Durrington Walls was never intended to be enclosed in the conventional sense. It was designed to be entered, exited, and worked within. Control was achieved not through exclusion, but through channelling movement along predictable routes.

This reframing is not radical. It simply requires taking the physical form of the ditch seriously and asking what it is mechanically suited to do. When that question is asked honestly, the answer is no longer “henge,” but hydraulic infrastructure.

And that infrastructure, as the next section will show, connects directly to the site’s most misunderstood element: the Northern Circle.

Introducing the North Circle: The Forgotten Half of the System

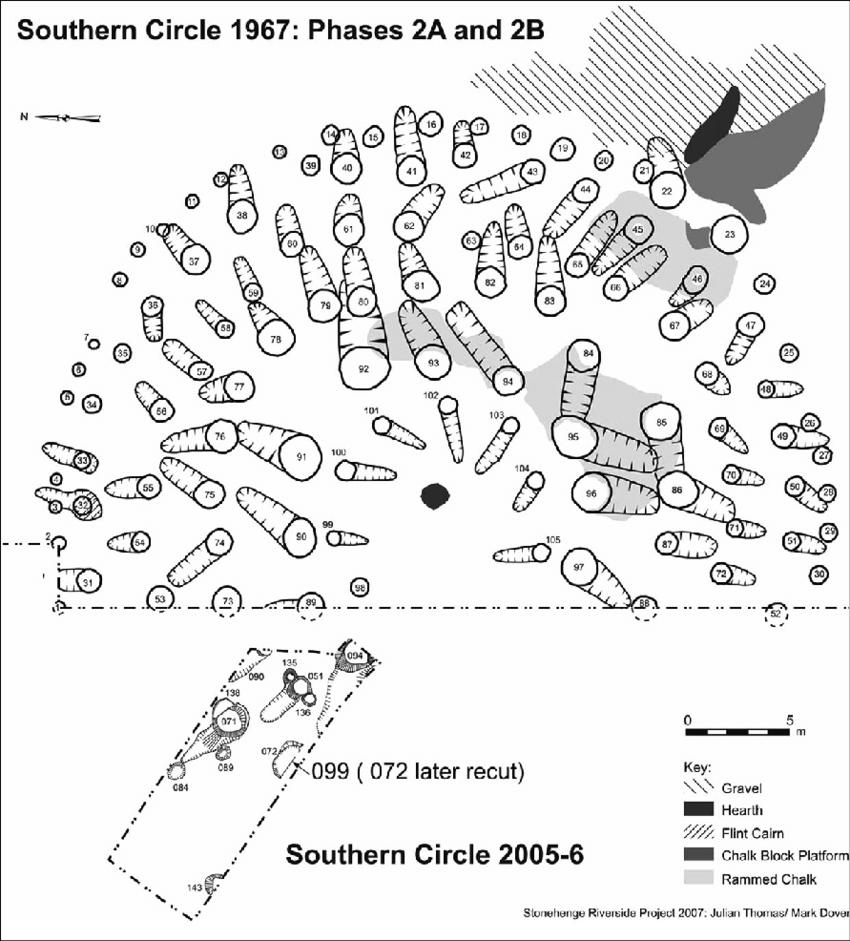

If the Southern Circle has been misread because it was forced into the category of a “great house,” then the North Circle has been misread because it has never fit comfortably into any category at all. Its awkwardness is not accidental. It is the clearest signal that the interpretive framework applied to Durrington Walls has been wrong from the outset.

The North Circle has typically been described in vague or dismissive terms: an incomplete timber circle, a subsidiary structure, a poorly preserved monument, or a ceremonial feature whose purpose remains unclear. These descriptions all share a common trait—they treat the North Circle as a failed version of something else, rather than asking what it actually is.

When examined on its own terms, the North Circle does not behave like architecture.

Architectural timber circles, whether domestic or ceremonial, tend to display several consistent characteristics. They favour regular spacing, because loads must be distributed predictably. They favour symmetry because roof structures require balanced support. They favour closure, because walls and roofs must enclose space. And they usually exhibit clear entrance logic aligned with internal organisation.

The North Circle exhibits none of these traits.

Instead, its post-holes are irregularly spaced, with zones of dense clustering and zones of relative absence. The arrangement is incomplete rather than closed. There is no coherent radial symmetry, no central focus, and no plausible roof geometry that could span the pattern without extraordinary and unnecessary complexity. Attempts to “complete” the circle or impose a regular geometry on it require heavy interpretive intervention—joining dots that the ground itself does not join.

This failure has often been attributed to truncation, later disturbance, or erosion. Yet this explanation becomes increasingly strained when the pattern is viewed as a whole. The irregularities are not random. They are structured. They display directionality, not decay.

Several alignments within the North Circle converge or taper, forming subtle V- or funnel-like shapes. These are not centred on a focal point, but biased toward particular orientations. Post density increases in some areas precisely where a structural or functional constraint would be expected, and decreases where openness would be advantageous. The plan reads not as a ring, but as a system of guidance and control.

Equally telling is what the North Circle does not attempt to do. It does not demarcate a sacred interior. It does not create an enclosed performance space. It does not separate inside from outside. Instead, it remains porous, open-ended, and accessible. These are not failures of design; they are the opposite. They indicate that containment was never the goal.

The persistent mistake has been to assume that posts must define walls.

Posts can just as easily define routes, channels, funnels, and working edges. In wetland and riverine environments, timber stakes are rarely used to enclose space. They are used to shape the movement of water, animals, and people. When the North Circle is read with this in mind, its structure stops looking defective and starts looking purposeful.

The spatial relationship between the North and South Circles reinforces this interpretation. The two are not redundant repetitions of the same idea. They occupy different positions within the enclosure, relate differently to slope and hydrology, and exhibit radically different construction logic. If they were both ceremonial timber monuments, built by the same community for the same symbolic purpose, this divergence would be inexplicable.

If they are components of a functional system, it is expected.

The Southern Circle, with its deep driven piles and heavy maintenance signature, behaves like a load-bearing interface—a place where weight, stress, and repeated use demanded structural robustness. The North Circle, by contrast, exhibits lighter construction, selective reinforcement, and directional geometry. It appears designed to work with movement rather than resist it.

This distinction has important implications. It suggests that Durrington Walls was not organised around a single focal monument, but around distributed functions. Different tasks required different structures, each optimised for its role within a larger operational landscape. In such a system, symmetry and monumentality are irrelevant. Efficiency and adaptability matter far more.

The North Circle has been forgotten not because it is unimportant, but because it does not conform to expectations. It does not announce itself as a monument. It does not demand reverence. It looks messy, irregular, and practical. In other words, it looks like infrastructure.

Recognising the North Circle as such does more than rehabilitate a neglected feature. It completes the picture begun with the Southern Circle and the ditch. It suggests that Durrington Walls was organised around movement and control, not static display. And it prepares the ground for a closer examination of the North Circle’s post-hole structure—an examination that points, quite consistently, toward a specific functional model.

That model is not architectural.

It is economic.

And it is aquatic

Reading the Post-Hole Structure Correctly

The North Circle at Durrington Walls has resisted interpretation primarily because it has been read as architecture. Once that assumption is removed, the post-hole pattern stops appearing chaotic and begins to behave coherently. The key is to read the structure directionally, not radially.

This section does not argue by analogy or symbolism. It reads the geometry as preserved in plan.

5.1 Directionality, Not Radial Design

Architectural timber circles—whether domestic or ceremonial—are organised radially. Posts are arranged around a centre, spacing is broadly consistent, and geometry prioritises balance. The North Circle does none of this.

Instead, the post-holes form directional alignments.

Several lines of posts converge, narrowing toward specific zones rather than orbiting a central point. These alignments do not mirror one another, nor do they divide space evenly. They are biased in orientation, favouring particular directions across the enclosure rather than reinforcing a circular interior.

Most importantly, these converging lines form funnel-like geometries.

Funnels are not architectural devices. They are control devices. They are used to guide movement—of water, animals, or material—toward predictable points. In buildings, funnels are undesirable; they create uneven load and instability. In capture systems, they are essential.

The absence of any true radial symmetry is therefore not a problem to be explained away. It is diagnostic. The structure was never intended to define a central space.

5.2 Variable Density and Open Ends

Equally revealing is the uneven density of post-holes across the structure.

Some zones show closely spaced posts, reinforced and clustered. Other areas are sparse, open, or entirely absent of posts. This pattern is inconsistent with walls or supports, which demand relatively uniform spacing to function structurally.

Instead, the density varies where stress or control would be required.

Reinforced zones occur at points of convergence and directional change. These are precisely the locations where pressure—hydraulic, biological, or mechanical—would be concentrated. Open zones occur where flow must continue unimpeded. This is not accidental variation; it is selective reinforcement.

Just as important is what the structure does not do.

The North Circle does not close.

There is no continuous ring, no sealed boundary, and no attempt to demarcate an “inside” and “outside.” Gaps are not randomly distributed but aligned with the directional geometry of the posts themselves. These open ends allow movement through the structure rather than confinement within it.

Containment is the defining feature of architecture.

Controlled permeability is the defining feature of movement systems.

The North Circle is consistently permeable.

5.3 Structural Implication

Taken together, these characteristics are decisive:

- Converging lines rather than radial symmetry

- Funnel-shaped geometries rather than enclosed spaces

- Biased orientation rather than balanced layout

- Reinforced zones paired with deliberate openness

- Absence of closure

This is not architectural geometry.

It is movement-control geometry.

The posts do not define walls. They define paths.

They do not enclose space. They shape flow.

Once read correctly, the North Circle ceases to be an “incomplete monument” and becomes a purpose-built control structure designed to operate within a fluid, changing environment. The geometry is functional, not symbolic, and it does exactly what it needs to do—no more, no less.

The remaining question is therefore not whether this structure controlled movement, but what kind of movement it was designed to control.

The answer to that question lies in a close comparison with known prehistoric and ethnographic examples of stake-built capture systems—specifically, fish traps and weirs.

That comparison is structural, not metaphorical, and it is the subject of the next section.

Fish Traps, Weirs, and Walkways: A Structural Match

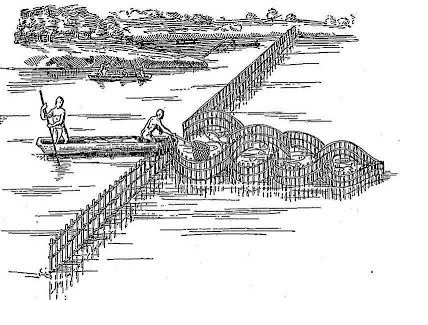

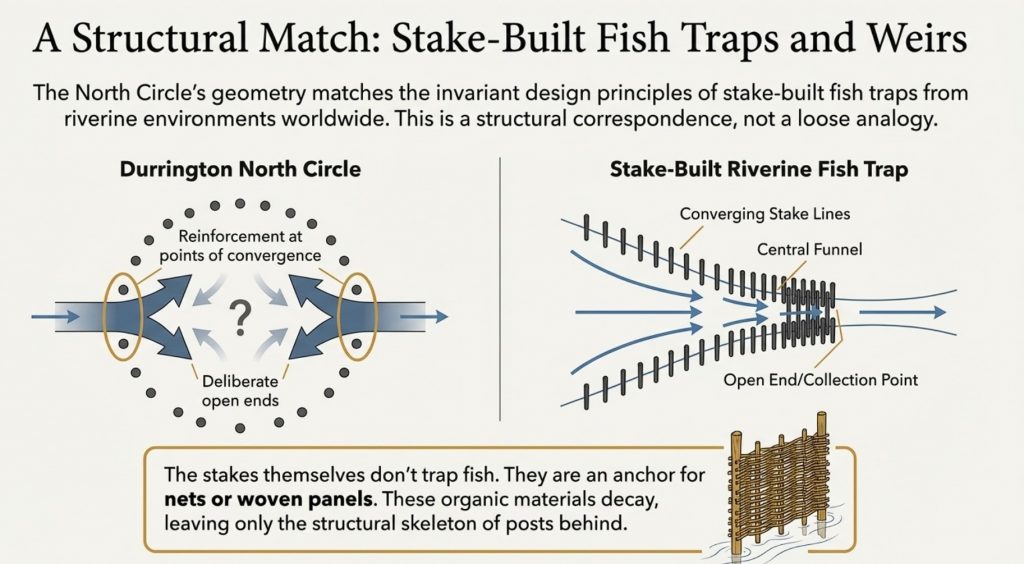

Once the North Circle is read as movement-control geometry rather than architecture, the range of plausible functions narrows rapidly. Among known prehistoric structures, one class matches the observed geometry with remarkable consistency: stake-built fish traps and weirs in riverine and wetland environments.

This is not a loose analogy. It is a structural correspondence.

Across Europe and beyond, fish traps built from driven wooden stakes share a small number of invariant design principles. These principles recur because they solve the same physical problems—guiding aquatic movement, managing variable water levels, and allowing human access for maintenance and harvesting. The North Circle conforms to these principles point by point.

6.1 Core Structural Traits of Stake-Built Fish Traps

Fish traps are not enclosures. They are guidance systems.

Their defining features include:

- Converging stake lines forming V- or funnel-shaped geometries

- Biased orientation aligned to current, slope, or tidal movement

- Selective reinforcement at points of pressure or convergence

- Open ends to prevent blockage and allow controlled release

- Replaceable driven posts, not permanent load-bearing timbers

These systems are designed to be worked, not admired. Stakes are driven, removed, replaced, and re-set as conditions change. Precision is functional, not geometric. Symmetry is irrelevant.

This description matches the North Circle far more closely than any architectural model ever proposed for it.

6.2 Funnel Geometry and Capture Logic

At the heart of most fish traps lies a simple idea: narrowing space increases predictability.

Fish moving with current, tide, or seasonal flow tend to follow the path of least resistance. Converging stake lines exploit this behaviour, reducing lateral escape while avoiding complete obstruction. The narrowing geometry concentrates fish into a manageable zone where they can be collected, speared, netted, or temporarily held.

The North Circle exhibits precisely this behaviour.

Its post alignments converge rather than encircle. Density increases toward specific zones rather than around a centre. There is no attempt to close the structure, because closure would be counterproductive. A fully enclosed trap risks blockage, damage, and loss of control during high flow.

Instead, permeability is engineered.

6.3 Walkways and Working Edges

A further diagnostic feature of fish traps is the presence of access routes.

Fish traps require continual human intervention:

- clearing debris

- repairing or replacing stakes

- harvesting catch

- adjusting geometry to seasonal conditions

For this reason, many prehistoric traps incorporate walkways or linear access edges—not formal platforms, but narrow zones where people can move alongside or into the structure without disrupting flow.

The North Circle includes precisely such linear elements.

These alignments do not contribute to enclosure or support. They make no sense as walls or screens. But as working edges, they are entirely intelligible. They allow access to key points within the structure while maintaining the integrity of the funnel geometry.

This feature is difficult to explain symbolically. It is trivial to explain functionally.

6.4 Driven Posts and Maintenance Cycles

Fish traps almost universally employ driven stakes rather than excavated post-holes. Speed of construction, ease of replacement, and adaptability matter more than permanence. Stakes are sharpened, driven into soft or saturated ground, and replaced as needed.

This construction logic mirrors what has already been observed at Durrington, particularly in the Southern Circle, but at a lighter scale appropriate to a capture system rather than a load-bearing platform.

Crucially, fish traps leave minimal artefactual signatures. They are economic infrastructure, not ritual deposition sites. Their primary archaeological trace is geometric: the pattern of post-holes themselves. This explains both the long-standing interpretive discomfort and the lack of “confirmatory” finds.

6.5 Structural Conclusion

The correspondence between the North Circle and known fish-capture systems is not based on superficial resemblance. It is grounded in:

- Directional funnel geometry

- Variable post density

- Open, non-enclosing design

- Evidence for driven, replaceable posts

- Presence of access alignments

Taken together, these traits identify the North Circle as a capture and control structure operating in a wetland context. Fish traps are not the only structures that control movement, but they are the only ones that match all of the observed characteristics without forcing the evidence.

The remaining task is to situate this structure within its environmental setting. Geometry alone suggests function; hydrology makes it inevitable.

That context—specifically the relationship between the North Circle, seasonal flooding, and the River Avon—is the focus of the next section.

6.6 Stakes Alone Do Not Capture Fish: The Role of Nets and Panels

It is essential to clarify a common misconception when interpreting prehistoric fish traps. Wooden stakes by themselves do not usually trap fish. Their primary role is to define geometry—to create funnels, guide movement, and provide anchoring points. Actual capture is achieved through flexible barriers fixed between those stakes.

Across ethnographic and archaeological examples, fish traps consistently combine:

- driven poles or stakes

- nets, woven reed panels, or wattle screens

- removable or seasonal barriers

These soft components perform the critical work. Nets stretch between adjacent stakes, forming semi-permeable walls that allow water to pass while restricting fish movement. Wattle panels can be lifted, lowered, or removed entirely, enabling selective harvesting and preventing damage during high flow.

This distinction is crucial for interpreting the North Circle at Durrington Walls.

The post-hole pattern defines where barriers were anchored, not the barriers themselves. The absence of preserved nets or panels is therefore not a problem. Organic woven materials decay rapidly, particularly in fluctuating wet–dry conditions. What survives archaeologically is the system’s structural skeleton: the stake pattern.

This also explains the variable spacing observed in the North Circle. Where fine control was needed—such as at funnel throats or retention zones—posts are closer together, providing frequent anchor points for nets or woven screens. Where guidance alone was sufficient, spacing increases, allowing flow without excessive material resistance.

Importantly, this arrangement allows for adaptive management. Nets can be tightened or slackened. Panels can be reconfigured seasonally. Sections can be opened to release non-target species or to clear debris. The post system remains, while the soft infrastructure changes.

This behaviour aligns precisely with what is seen at Durrington. The North Circle shows:

- permanent stake positions

- selective reinforcement

- no attempt at full enclosure

- evidence for ongoing maintenance

These traits are incompatible with rigid architectural forms, but entirely consistent with net-assisted capture systems.

The presence of linear access alignments—interpreted in the previous section as walkways or working edges—becomes even more significant in this context. Nets must be set, checked, lifted, repaired, and cleared. This requires controlled human access along the structure. The North Circle provides that access structurally, without interfering with flow or capture zones.

Finally, this model explains why such a system would coexist with the Southern Circle platform rather than replace it. Fish traps capture and concentrate fish; platforms are needed to:

- process catches

- distribute food

- store or dry fish

- provision larger groups

The two structures are complementary, not redundant.

Hydrology and the Avon Connection

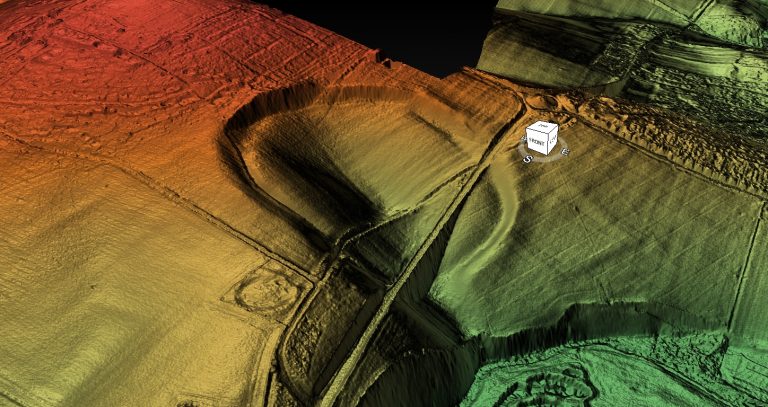

The functional interpretation of the North Circle as a net-assisted fish capture system only becomes fully coherent when placed within its hydrological context. Without water, the structure is inexplicable. With water, it is inevitable. The controlling variable is not symbolism or ritual intent, but the behaviour of the River Avon system during the Mesolithic and early Holocene.

Post-glacial Britain was not a dry, stable landscape punctuated by neatly contained rivers. It was a wet, dynamic environment characterised by elevated groundwater tables, seasonally inundated floodplains, and laterally mobile channels. Chalk landscapes in particular respond to rising water tables by spreading water across broad areas rather than confining it to discrete banks. Springs emerge unpredictably, coombes fill, and low gradients produce slow-moving, shallow flows ideal for fish movement—and capture.

In such conditions, the Avon would not have been the narrow, incised river seen today. It would have occupied a much broader floodplain, with multiple shallow channels, seasonal overbank flow, and temporary wetlands forming and dissipating across the valley floor. This is precisely the kind of environment in which stake-built fish traps are most effective.

Durrington Walls’ location places it at a critical junction within this system. Situated above the Avon, at the head of a coombe, the site occupies a natural transition zone between higher ground and floodplain. This is where water slows, spreads, and becomes manageable. Fish moving upstream or laterally with seasonal flooding are naturally funnelled into such areas. Human intervention needs only enhance an existing pattern.

The North Circle sits downslope from the main enclosure, in a position consistent with intermittent or seasonal water flow rather than permanent submersion. This is important. Fish traps are rarely placed in deep, fast-flowing channels. They are placed where water is shallow enough to control, slow enough to guide, and predictable enough to exploit repeatedly. The North Circle occupies exactly such a zone.

The Southern Circle platform, by contrast, occupies a slightly higher and more stable position. This spatial separation is not accidental. Capture systems are messy, dynamic, and exposed to fluctuating conditions. Processing and redistribution require firmer footing. The two structures are therefore arranged along a hydrological gradient rather than a ceremonial axis.

When the ditch system is reintroduced into this picture, the integration becomes clearer still. The broad flat-bottomed ditch functions as a controlled water body—part basin, part channel—linking capture zones, working areas, and access points. Smaller linear ditches act as secondary channels, draining or redistributing water as conditions change. Together, these features create a managed waterscape rather than a bounded monument.

This model also explains why Durrington Walls does not behave like a settlement. Permanent domestic occupation is poorly suited to fluctuating wet ground. Infrastructure, however, thrives on predictability rather than permanence. Fish runs are seasonal but reliable. Flooding is disruptive but cyclical. A site organised around provisioning and aggregation does not need year-round habitation; it requires timing.

The Avon connection further explains the scale of the system. Fish capture at this level is not a subsistence afterthought. It is provisioning infrastructure capable of supporting large numbers of people over short periods. This aligns neatly with isotopic evidence from nearby sites indicating the movement of cattle over long distances. Aggregation events require reliable food sources. Fish, preserved by drying or smoking, provide exactly that.

Crucially, none of this requires speculative reconstructions of ritual behaviour. It requires only an honest assessment of how water behaves in chalk landscapes and how people respond to it. Once hydrology is treated as an active force rather than a passive backdrop, the site stops fragmenting into unrelated anomalies and starts functioning as a system.

The North Circle does not need to be reimagined as symbolic.

The Southern Circle does not need to be elevated into a hall.

The ditch does not need to enclose anything.

They need only to be wet.

With the hydrological framework in place, the final step is to integrate all components—North Circle, Southern Circle, ditch, and channels—into a single operational model. That integration, and its wider implications for how Durrington Walls is understood, forms the basis of the next section.

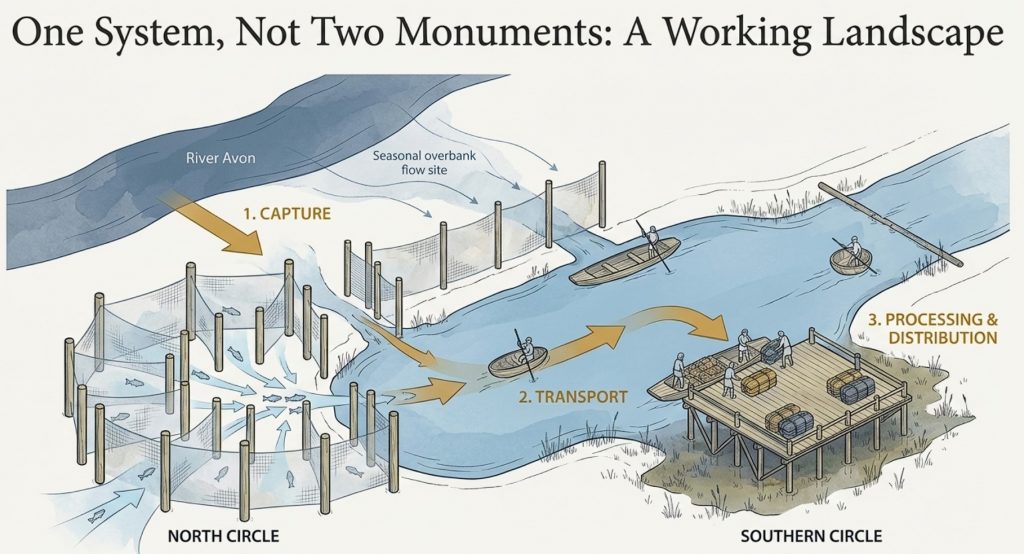

One System, Not Two Monuments

Once the North Circle is understood as a net-assisted fish capture structure operating within a flooded landscape, and the Southern Circle as a pile-supported platform adapted to wet ground, the most important interpretive shift becomes unavoidable: these were not two monuments serving parallel symbolic roles. They were two components within a single operational system, each designed for a different task but dependent on the other to function effectively.

Traditional interpretations have treated the two circles as variants of the same idea—timber equivalents of stone monuments, perhaps reflecting social or ritual dualism. This approach struggles to explain why the two structures differ so profoundly in construction logic, geometry, maintenance signature, and placement. If they were built by the same community, at roughly the same time, for the same symbolic purpose, such divergence would be inexplicable.

If they were built for different functions, it is exactly what we should expect.

The North Circle, with its directional geometry, variable post density, open ends, and reliance on nets or panels fixed between stakes, is optimised for capture and control. It operates in shallow, slow-moving water. It is light, adaptable, and continuously reworked. Its success depends on guiding movement rather than resisting it.

The Southern Circle, by contrast, is heavy, vertical, and structurally intensive. Driven piles, pointed bases, extraction scars, and repeated refitment indicate a structure designed to carry load and withstand repeated use. It is not concerned with guiding movement, but with supporting weight—people, animals, goods, or equipment—above unstable ground.

These are not alternative expressions of monumentality. They are complementary solutions to different problems posed by the same environment.

The spatial relationship between the two reinforces this reading. They are positioned along a hydrological gradient rather than a symbolic axis. Capture occurs where water spreads and slows; processing and redistribution occur where footing is more reliable. Movement between the two is short, direct, and controlled, minimising loss and maximising efficiency. This is how working landscapes are organised.

The ditch system binds these elements together. Far from enclosing or separating, it facilitates the circulation of water, people, and resources. The broad flat-bottomed ditch provides a holding basin and access route. Smaller linear ditches redistribute flow internally. Together, they create a managed network rather than a ceremonial boundary.

This integrated system also explains features that have long resisted interpretation. The absence of domestic architecture ceases to be a problem once the site is recognised as seasonal or task-specific rather than permanently inhabited. The lack of ritual deposition around the North Circle becomes irrelevant once its function is understood as economic rather than symbolic. The repeated maintenance of the Southern Circle stops being anomalous and becomes expected.

Importantly, this model does not diminish the social or cultural importance of Durrington Walls. On the contrary, it elevates it. The infrastructure of this scale implies coordination, planning, and shared knowledge. Fish capture systems require an understanding of seasonal cycles, water behaviour, and animal movement. Platforms that support heavy, repeated use demand engineering competence and long-term investment.

What it does reject is the idea that meaning must always precede function.

In many prehistoric contexts, function generates meaning, not the other way around. Aggregation sites become socially significant because they work—because they feed people, enable exchange, and bring groups together at predictable times. Ritualisation follows success; it does not replace it.

Seen in this light, Durrington Walls begins to resemble other large-scale provisioning landscapes known from wetland contexts worldwide. These are places where food is captured, processed, and distributed; where people gather seasonally; where social bonds are renewed around shared labour rather than abstract symbolism.

The persistent attempt to read Durrington as a dry ceremonial complex has obscured this possibility for decades. Once water is reintroduced as the organising force, the site stops fragmenting into unrelated anomalies. The North Circle, Southern Circle, ditch, and channels lock together into a coherent whole.

They were never meant to be read separately.

The next question, then, is not how this system functioned internally—that is now clear—but what it was capable of supporting. The answer lies in the scale of provisioning required to sustain aggregation, movement, and long-distance exchange. That evidence comes from the animals themselves.

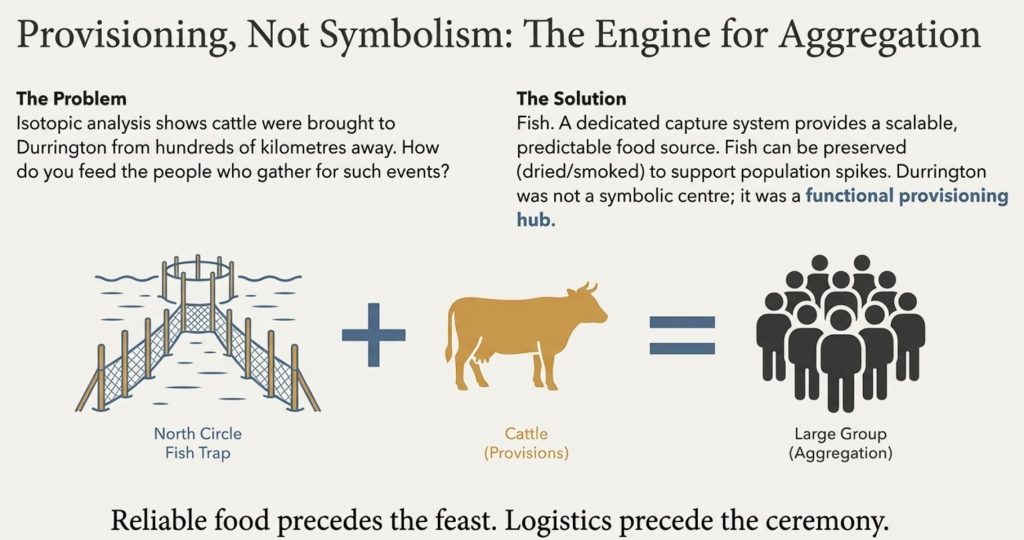

Provisioning, Not Symbolism: Fish, Cattle, and Aggregation

The integrated model proposed for Durrington Walls—combining fish capture, water-managed access, and load-bearing platforms—only makes sense if it served a substantial provisioning role. Infrastructure of this scale is not built to support small household groups. It is built to sustain aggregation: the periodic gathering of large numbers of people for social, economic, or logistical purposes. The archaeological evidence strongly supports this interpretation.

One of the most compelling lines of evidence comes from animal remains, particularly cattle. Isotopic analysis of cattle teeth from the Durrington area has demonstrated that animals were brought to the site from hundreds of kilometres away, including regions as distant as northern Britain. This level of movement cannot be explained by casual exchange or local herding. It implies planned transport, coordination across landscapes, and a clear reason for convergence.

Moving cattle over such distances presents a fundamental logistical challenge: feeding people during aggregation events. Large numbers of humans and animals arriving simultaneously create immediate provisioning demands. Terrestrial resources alone are insufficient unless extensive storage or long-term settlement is present. Durrington Walls shows no convincing evidence for either.

Fish solve this problem elegantly.

Riverine and wetland fish resources are highly productive, predictable, and scalable. Seasonal runs concentrate biomass naturally, allowing capture systems to harvest large quantities with relatively low labour input once infrastructure is in place. Fish can be consumed fresh, but more importantly, they can be preserved—dried or smoked—for use over extended periods. This makes them ideal for supporting short-term population spikes.

The presence of a dedicated fish capture system adjacent to a processing and redistribution platform transforms Durrington from a symbolic gathering place into a functional provisioning hub. Fish provide the caloric baseline that allows cattle to be moved and exchanged without exhausting local resources. In this context, cattle become socially and economically meaningful assets rather than primary food sources.

This also clarifies why the North Circle shows no signs of ritual elaboration. Fish traps are invisible when they work well. Their success is measured in output, not display. What mattered was reliability, not monumentality. The South Circle, by contrast, may well have acquired social significance over time—not because it was symbolic in origin, but because it became central to the site’s functioning.

Aggregation sites do not need to be permanently occupied to be socially powerful. In many ethnographic and archaeological examples, the opposite is true. Places that are visited seasonally, but reliably, acquire meaning precisely because they structure time, movement, and interaction. Durrington Walls fits this pattern far better than that of a permanent village.

The combined fish-and-cattle model also resolves the persistent question of scale. Why build such large earthworks and timber structures if they were not continuously inhabited? The answer is that scale reflects capacity, not population. Infrastructure is built to accommodate peak demand, not average use. The apparent over-engineering of the ditch, the maintenance-heavy nature of the Southern Circle, and the extensiveness of the enclosure all make sense once the site is understood as an aggregation and provisioning landscape.

This interpretation further undermines attempts to explain Durrington solely through ritual or cosmology. Ritual does not require such logistical redundancy. Symbolism does not demand maintenance cycles. Meaning does not require fish traps.

Provisioning does.

None of this denies the possibility that social or ceremonial activities occurred at Durrington Walls. On the contrary, they almost certainly did. But those activities were enabled by an infrastructure that worked first. The sequence matters. Food precedes feast; logistics precede ceremony.

By reframing Durrington as a provisioning hub rather than a symbolic centre, long-standing interpretive tensions dissolve. The absence of domestic architecture is no longer a problem. The scale of construction is no longer puzzling. The presence of multiple specialised structures becomes expected rather than anomalous.

The final issue to address is not whether this model fits the evidence—it does—but why it has been so persistently overlooked. That question speaks less to the site itself and more to the habits of the discipline that has studied it.

Woodhenge Reconsidered: Why a Real Timber Monument Was Built

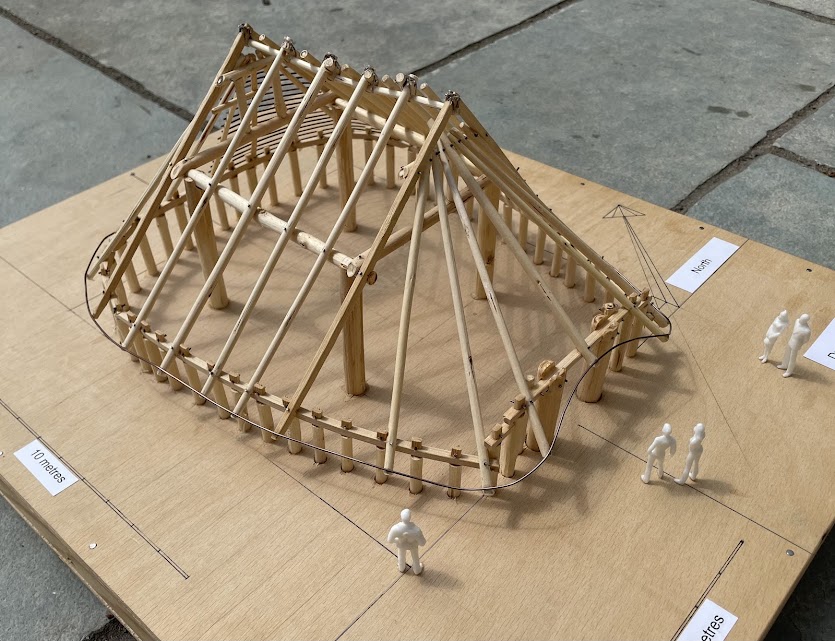

Any serious reinterpretation of Durrington Walls must confront an uncomfortable but decisive fact: Woodhenge exists only metres away, and it behaves entirely differently. This proximity removes any excuse for misinterpretation. If archaeologists wish to argue that the Southern Circle and the North Circle are misunderstood timber monuments, they must also explain why Woodhenge—built in the same landscape, by the same culture, using the same materials—follows a completely different construction logic.

When the excavation evidence is read honestly, Woodhenge is exactly what orthodox archaeology claims it to be: a dry-land timber monument. Its post-holes are excavated, not driven. Bases are flat or scooped. Spacing is regular and concentric. Construction appears largely single-phase. There is no evidence of refitment, no extraction scars, and no requirement for continual maintenance. This is what architecture looks like when it is built on stable ground.

In other words, Woodhenge behaves precisely as a monument should.

This matters because it means cultural incompetence, technological limitations, or preservation bias cannot explain away the anomalous behaviour observed at the Southern Circle. The builders clearly understood how to construct dry-land timber structures when they wanted to. They did so successfully at Woodhenge.

The question, then, is not whether they could build a great house or ceremonial monument at Durrington.

It is why they chose not to – The answer lies in function.

Woodhenge occupies a slightly higher, drier position in the landscape, removed from the most unstable ground and from the immediate water interface. Its geometry is regular, enclosed, and inward-facing. It defines a space rather than guiding movement. Everything about it suggests a static, symbolic structure—a place designed to be stood within, observed, or marked, rather than worked.

By contrast, the Southern Circle is engineered for load, not enclosure. Its driven piles, pointed bases, extraction scars, and repeated refitment demonstrate adaptation to unstable ground and continual stress. It is outward-facing, practical, and structurally redundant. These are not symbolic choices; they are engineering responses.

The North Circle pushes this contrast even further. Where Woodhenge is concentric and enclosed, the North Circle is directional and open. Where Woodhenge emphasises symmetry, the North Circle emphasises flow. Where Woodhenge creates a place, the North Circle creates a process.

Seen together, the three structures form a deliberate functional triad:

- Woodhenge: a true dry-land timber monument, static and symbolic

- Southern Circle: a pile-supported working platform, load-bearing and maintained

- North Circle: a net-assisted capture system, guiding movement in water

This arrangement is not accidental, nor is it contradictory. It reflects task differentiation within a single managed landscape.

Woodhenge demonstrates that symbolism had a place here—but not everywhere. Meaning was spatially segregated from function. Ritual did not need to sit on unstable ground. Infrastructure did not need to be monumental. Each structure was optimised for its role, not forced into a single interpretive category.

This observation alone dismantles the “timber monument everywhere” assumption that has distorted interpretations of Durrington Walls for decades. The presence of Woodhenge proves that the builders were capable of symbolic timber architecture. The absence of similar behaviour at the Southern and North Circles proves that those structures were intended for something else.

Woodhenge is not the key to explaining Durrington by analogy.

It is the key to explaining why analogy fails.

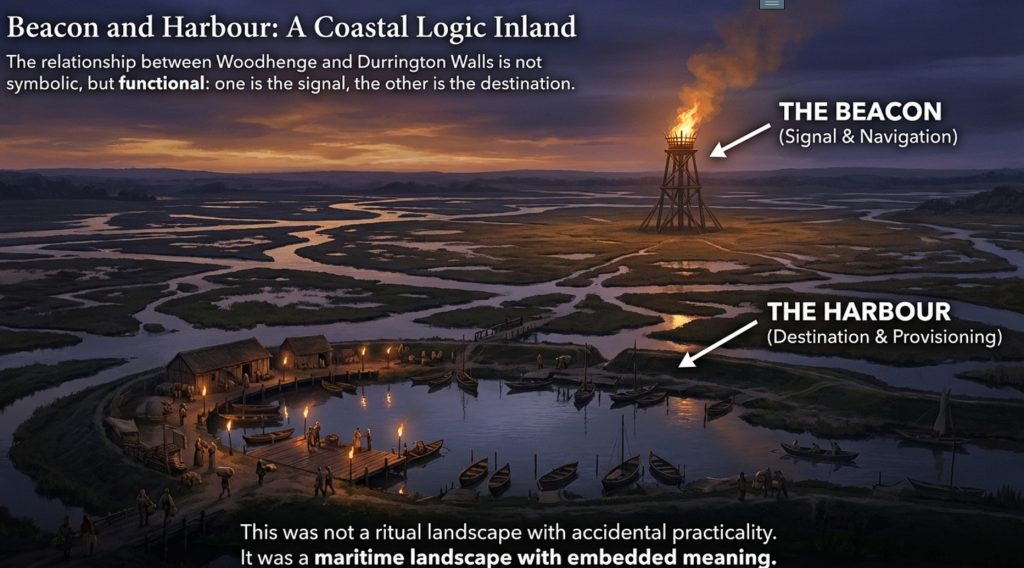

Why the Site Is There: Woodhenge as Beacon, Durrington Walls as Harbour

Once the structures at Durrington Walls are understood functionally—rather than symbolically—the final and most important question can finally be adequately asked: why here? Not why these monuments look the way they do, but why this landscape was chosen in the first place.

The answer lies not in cosmology, ritual abstraction, or seasonal feasting alone, but in navigation, visibility, and access.

The relationship between Woodhenge and Durrington Walls has been consistently mischaracterised as a symbolic pairing. In reality, it is a functional pairing—beacon and harbour, signal and destination.

Woodhenge as a Beacon, Not a Gathering Place

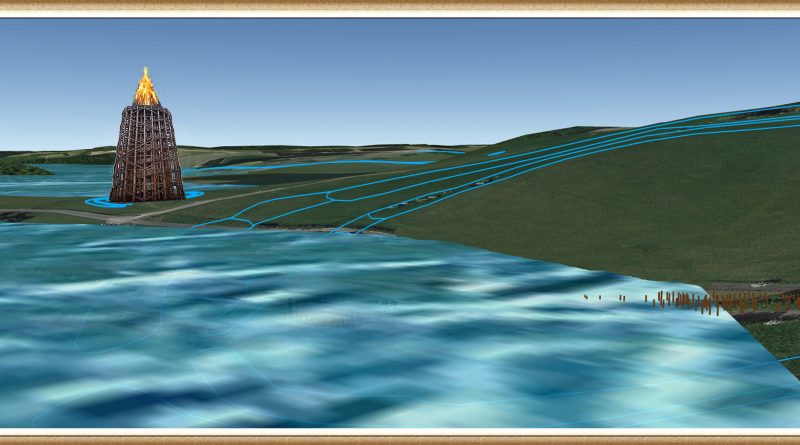

Woodhenge occupies a slightly elevated, dry position in the landscape, visible across the surrounding floodplain. Its regular concentric structure, excavated post-holes, and lack of maintenance scars indicate a static, dry-land monument rather than a working platform. This alone sets it apart from the Southern Circle at Durrington.

But crucially, Woodhenge also occupies the wrong position to be economically useful in provisioning, capture, or water management. It does not sit at a hydrological interface. It does not control movement. It does not support load. It does not guide flow.

What it does do exceptionally well is stand.

When the post heights implied by the excavated sockets are reconstructed, Woodhenge becomes a tall vertical structure in an otherwise low-relief landscape. In a flooded or waterlogged plain, such verticality is not ornamental—it is navigational. A timber ring supporting a raised superstructure, fire platform, or beacon would have been visible from a considerable distance across open water or marsh.

This places Woodhenge firmly within a known class of prehistoric structures: fire beacons and navigation markers, used to attract, guide, and signal to approaching vessels. Such beacons are not inventions of historic or classical societies. They are a logical response wherever waterborne movement dominates, and shorelines are unstable or indistinct.

Woodhenge does not need to be interpreted as exclusively ritual to fulfil this role. A beacon is both practical and symbolic. Fire marks presence. Height marks authority. Visibility marks safety.

Durrington Walls as Harbour and Trading Point

If Woodhenge is the signal, Durrington Walls is the destination.

The scale, layout, and infrastructure of Durrington Walls are entirely consistent with a harbour complex rather than a village. The broad flat-bottomed ditch functions as a controlled basin. The Southern Circle provides a pile-supported platform for unloading, staging, and redistribution. The North Circle captures and concentrates aquatic resources. Linear channels manage movement internally.

This is what harbours look like before stone quays and masonry piers.

In a Mesolithic or early Holocene environment dominated by water transport, harbours do not require monumental stonework. They require predictable access, controlled grounding, and reliable provisioning. Durrington provides all three.

The presence of long-distance cattle movement reinforces this interpretation. Harbours are exchange points. They are where inland routes meet water routes. They are where goods arrive, are processed, redistributed, and moved on. Cattle arriving from hundreds of kilometres away do not converge on ritual centres by accident. They converge on logistical hubs.

Durrington Walls occupies precisely such a node: accessible from the Avon system, provisioned by fish capture, stabilised by platforms, and signalled by a visible beacon.

Dual-Purpose Monuments and Excarnation

This civilisation did not separate function and meaning. It layered them.

The same structures that guided ships and provisioned people could also serve mortuary functions. Elevated timber platforms—especially those associated with fire and visibility—are ideal for excarnation. This practice is well attested ethnographically, including the Silent Towers of India, where bodies are exposed on raised structures for defleshing by birds.

Woodhenge’s elevated, open timber form is well suited to such use. Fire, height, and exposure are not contradictions; they are complementary. A beacon can signal to the living while serving the dead. A harbour can receive goods and bodies alike. In water-based cultures, the boundary between journey, trade, and afterlife is often deliberately thin.

This dual-purpose logic explains why these structures were invested with care but not rebuilt endlessly. Their power lay in continuity, not replacement.

Conclusion: A Coastal Logic Inland

Woodhenge and Durrington Walls together form a system that only looks strange if interpreted through dry-land assumptions.

Seen through the lens of navigation and water management, the logic is simple:

- Woodhenge marks the place

- Durrington Walls services the place

- Water connects the place

This is not a ritual landscape with accidental practicality.

It is a maritime landscape with embedded meaning.

The site exists where it does because it had to.

Podcast

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

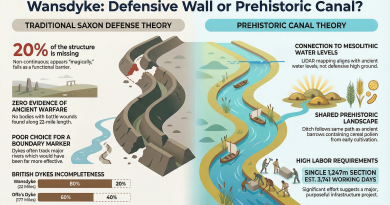

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?