Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

Case Study – The Roman Military Way……… (Extract from the Book – The Hadrian’s Wall Enigma)

Many, new to the famous Whin Sill section of the Roman Wall frontier, confuse the Military Road (B6318) with the Roman Military Way. They have nothing in common, either in time or purpose. In fact, the Military Road was only constructed after the Jacobite Rising of 1745, in large part upon the ruin of the wall!

The Romans created the Military Way (according to Historic England) as the means of speedily relaying goods along the line of the wall. It was used to support the running of the frontier wall during the Roman period.

When Hadrian’s first grand plan was executed, The Stanegate (another Case Study in this book) was created as an east/west military road. But when Hadrian’s successor, Antonius Pius, pushed the frontier north, through the isthmus between the Forth and Clyde, creating the Antonine Wall (yet another case study in this book), the supply road was installed integral to the turf-banked frontier linking the forts and milecastles.

Over time, when the frontier retreated to consolidate upon the original Hadrianic line, it was essential to have the same flexibility close to the Hadrian’s Wall.

But does it exist, and what was it for in reality?

If we look at the first instance of this ‘alleged’ road, we need to go to Section E (of our Map) – Historic England (HE) section 1010979, this road starts some 24.2 km from the western flank of Hadrian’s Wall – which ‘begs the question’ – what was used to link the 20% of the wall when this road was missing?

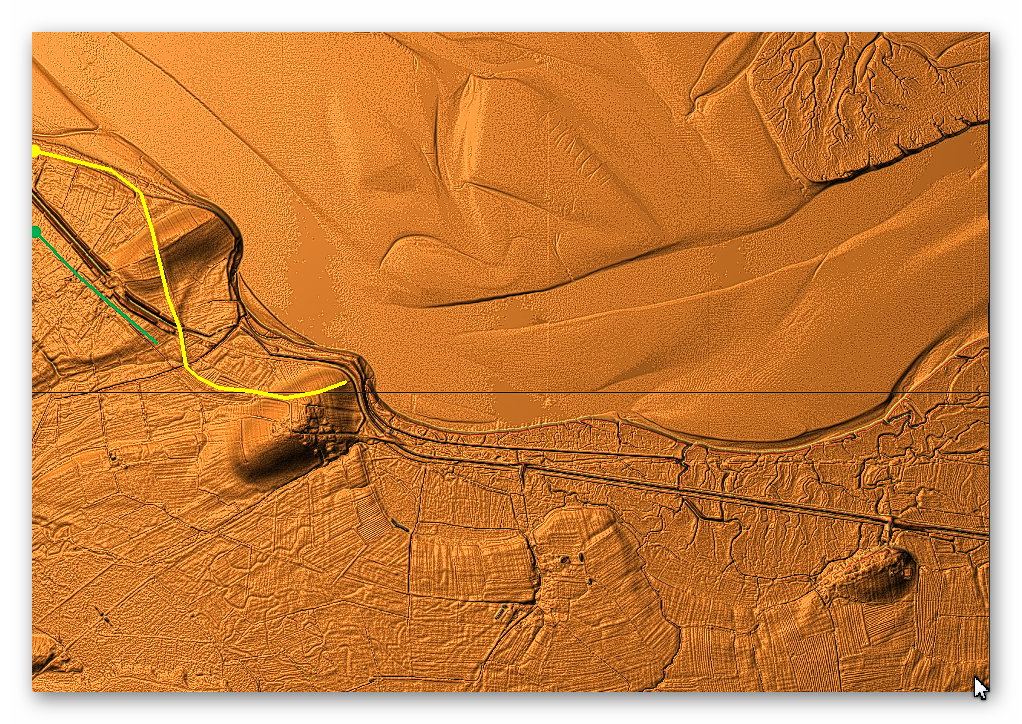

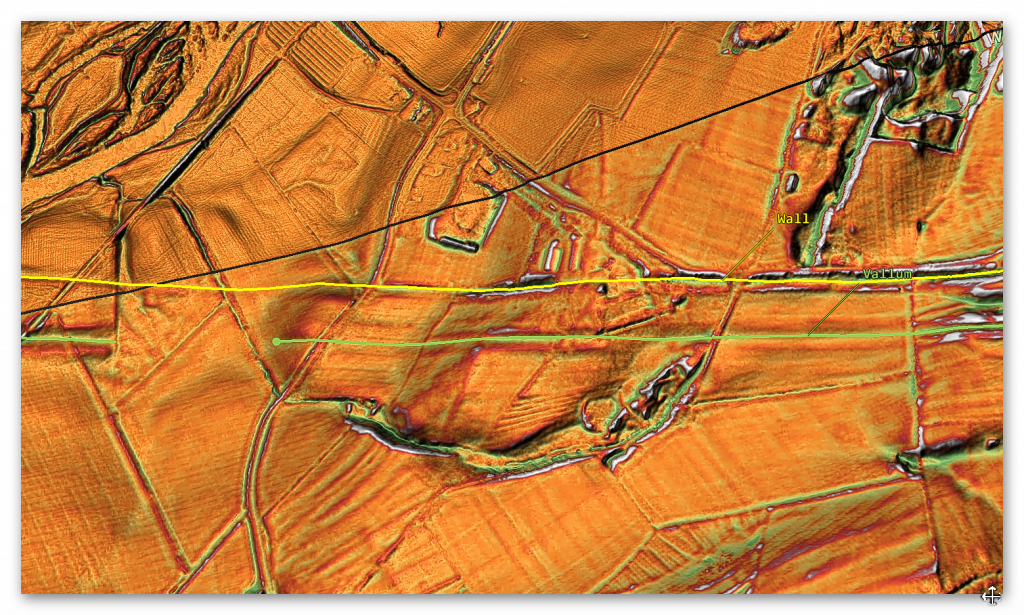

When we do eventually find this ‘road’ (according to archaeologists), another mystery occurs – there is nothing on LiDAR! Further investigation into why Historic England (HE) included it in its scheduling reports indicates that – it only existed in ‘short distances’, or it’s invisible, and maybe under another road?

Section E (HE:1010979)

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has been identified for a short distance to the east of Wallhead.

There are no remains visible on the surface except for a short section of a turf-covered mound, 4m-5m wide and up to 0.4m high.

Its course was confirmed during excavation in 1894 by Haverfield. The road consisted of a gravel layer laid over larger stones with a stone kerb and central spine. Its survival here was confirmed by a geophysical survey in 1981. However, the unusual survival of this section suggests the possibility that it was reused in the medieval period serving as access to Bleatarn Quarry.”

This problem of misidentified comes about when archaeologists go out looking for a ‘perceived structure’ to satisfy an objective.

Section H (HE 1010996) is some 33.5 km from the Western start of the wall (27.5%) – so what do we have here?

“The exact course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, is known intermittently throughout this section where it survives as an earthwork feature.

Opposite the disused quarry west of Bankshead Farm the Military Way survives as a terrace, 3m-5m wide, on the north side of an old hedge line. Occasional rises in hedge lines denote traces of its course.”

Again it does not appear on the OS (1800) map, and what we find on the LiDAR maps seems to indicate that it is linked to the Old Quarry rather than ‘connecting turrets and milecastles’?

Moreover, the Vallum has disappeared from this section and what we might be seeing is a shallow bank of the Vallum of a replacement.

Section I (HE: 1010994)

“Excavations in 1911 by Simpson showed there to be two early floor levels as well as late pottery, demonstrating that the turret had continued in use, unlike many other turrets. The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known throughout this section. West of the fort it survives as an intermittent low linear mound, 0.1m in maximum height. East of the fort, a geophysical survey in 1986 by Walker confirmed the existence of the Military Way below the turf cover.”

There looks like a partial road in-between the Wall and The Vallum. Which may join the Station (Amboglanna) to the Milecastle in that region – but it’s not a connecting road that continues past this isolated point (less than 1000m in length)?

The road now again disappears for another 7km, and then it reappears again in Section I on the OS maps.

Section J:

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, is known throughout this section. It is visible as a low causeway, 0.2m high, or as a terrace, 5m wide, winding between rock outcrops to the south of the wall. Turret 45a is situated on a high point on Walltown Crags with extensive views in all directions. It survives as an upstanding exposed feature, which is consolidated and in the care of the Secretary of State.”

“The road which connected the milecastle to the Military Way survives as a causeway 3.5m wide and 0.2m high. Milecastle 45 is situated on the crest of Walltown Crags with commanding views to the north and south.”

“It survives as a low turf-covered causeway 5.5m wide and up to 0.5m high, or as a terrace in the hillside with a minimum width of 3m. It is straight for most of its course except where it deviates around rock outcrops.”

“West of the Cockmount Hill Plantation the foundations of two large regularly laid out rectangular buildings overlie the Military Way, using it as a hard standing. Their form suggests they are post-medieval or later in date. South east of King Arthur’s Well a spur road branched off the Military Way, the remains of which can be seen as a turf-covered causeway leading south-east towards Lowtown.”

“Its course from the Caw Burn is known where it survives as a low turf-covered mound, 6m to 8m wide and 0.2m to 0.5m high. Occasional sections of this low turf-covered causeway reappear on the line up to the east gateway of Great Chester’s fort.

Beyond the field boundary west of the fort the Military Way is visible again as a discontinuous terrace with a slightly sinuous course which avoids the rock outcrops. Field gates are positioned on its course at the east and west end of this stretch.

A road linking the Military Way and the Stanegate Roman road to the south via Great Chester’s fort is overlain by the modern trackway to Great Chesters Farm which enters the fort through the south gateway.”

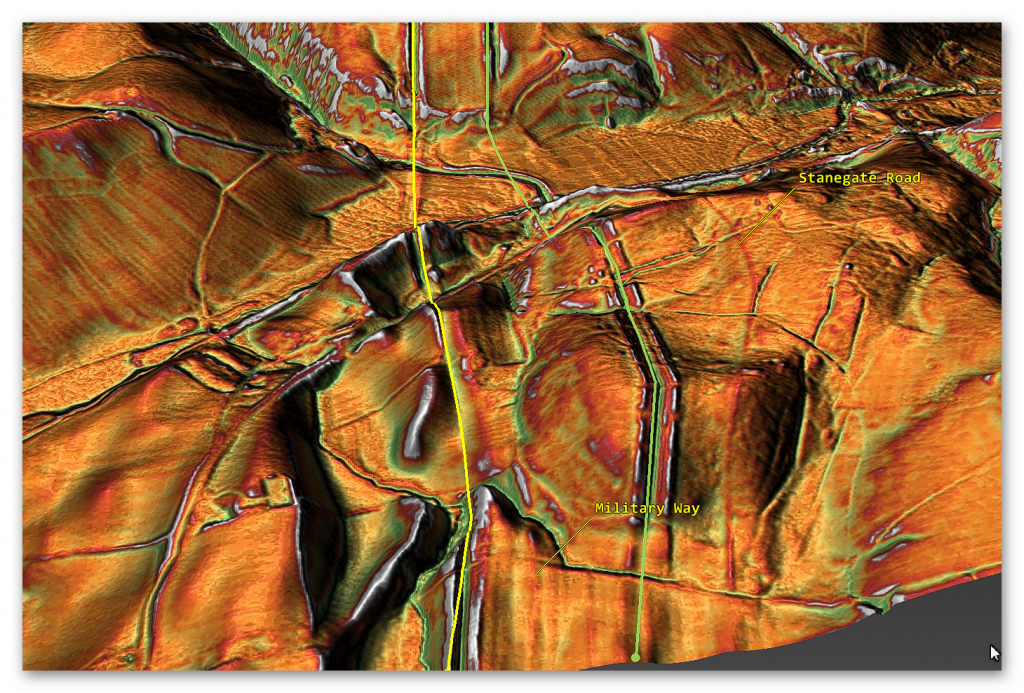

From these strong descriptions, we would imagine that the course and evidence for the road will show strongly on LiDAR, but it’s totally invisible but for a small 260m section.

Section K (HE: 1010975):

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts is known throughout this section except around Cawfields Quarry where its precise course has not yet been confirmed. It survives as a linear causeway which is most prominent at the east end of this section. Here it measures between 3.5m and 5.2m wide with a revetment containing large stones on the south side and with evidence of a stone kerb. Further west the causeway, where extant, averages about 0.1m in height and 7m in width.

Where there is no trace of the causeway the line of the road has been identified by changes in vegetation growth with grass growing less well above the former road surface. Around Cawfields Quarry the remains of the Military Way may have been destroyed by the quarry, however, it is possible that here the Military Way was built on the line of the Vallum, as it was further to the east at the crossing site of the Caw Burn and thus survives. About 200m east of milecastle 42 and 10m to the south of the Military Way is a fallen Roman milestone. It measures 1.38m high by 0.4m by 0.3m. It is oblong in shape and crudely rounded at the corners. This uninscribed milestone now lies in long grass. Two other milestones from this vicinity have been removed and are now in Chesters museum.”

The LiDAR map shows that the road did not go to the Quarry but terminated in the River Valley (Like the Vallum) – was there a bridge across (no foundations) are shown on the LiDAR map.

Section HE: 1010973 suggest that:

“Its course is marked usually by a slight causeway, up to 0.2m high, or by differing vegetation marks seen in grass colour. This differentiation in vegetation cover reflects differing growing conditions on the compacted road surface. It is best preserved where it crosses a gully running into Green Slack. Here it survives as a built-up causeway, 1.7m high and 2m wide. South of milecastle 41 the causeway survives up to 0.7m high with kerbstones on its south side.”

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, survives well as a linear causeway throughout this section. Some stone is visible on the south scarp, where it has been built up to make a level surface. This scarp appears to have had a stone revetment. The south scarp averages 0.4m in height, although it reaches up to 1.2m high in places. West of Peel Farm the Military Way is overlain by the road to Steel Rigg car park. To the south of Sycamore Gap are the remains of a prehistoric field boundary running roughly from north to south, probably dating to the Bronze Age.“

“The Roman Military Way overlies this boundary, indicating that it is certainly pre-Roman. The peat bog, which has grown over remains of this boundary further to the south, is of Bronze Age origin. A second boundary is located running transversely to the Sycamore Gap boundary, to the west of it, south of the Military Way. Their assumed junction is masked by the peat bog which has built up to the south.”

Section L (HE:1010964):

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts survives as a turf-covered linear mound throughout most of this section. It is visible as a disturbed causeway averaging 5m wide with traces of a stone revetment on the south side. It was partly excavated between 1978 and 1980 when it was shown to have a damaged metalled surface 4m wide, a stone revetment on the south scarp, and to have been overlain by later roadways. Branch roads survive linking the Military Way with the south gates of both milecastles 35 and 36. At milecastle 35 the low, uneven turf-covered mound of the causeway is up to 5.5m wide and 0.2m high.”

Section M (HE:1010963):

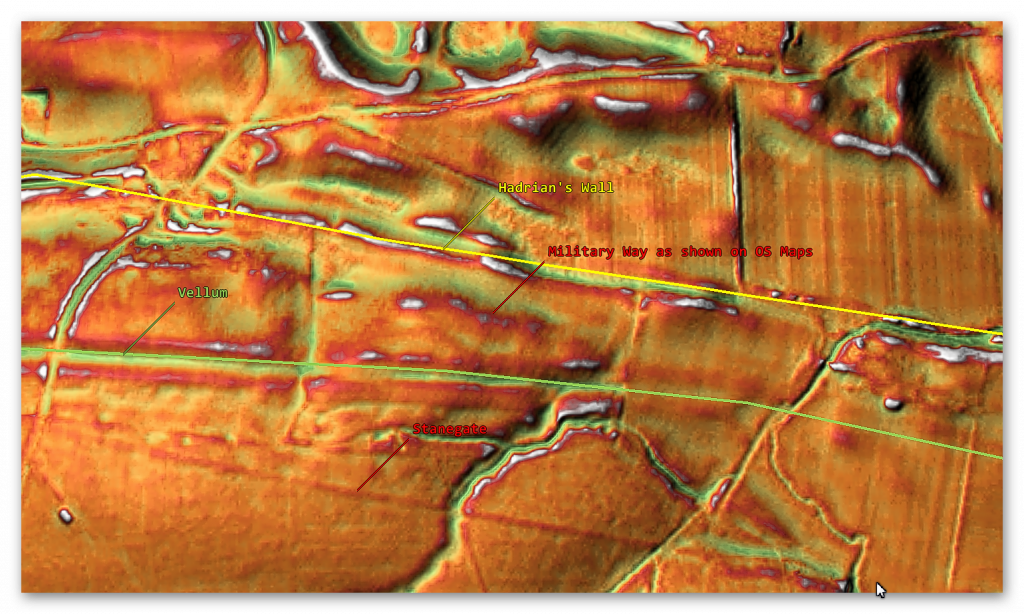

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, was carried on the north mound of the Vallum in the east half of this section. Its buried remains survive below grassland east of milecastle 33, until the B6318 road coincides with the north mound of the Vallum where it lies below the modern road surface.”

“South of turret 33b the Military Way leaves the north mound of the Vallum and follows a course parallel to that of the wall. Here it survives as a distinct linear mound up to 6m wide and up to 0.3m high. The Vallum survives well as an upstanding earthwork visible on the ground throughout this section. It runs roughly parallel with the line of the wall until south of turret 33b where it turns to the south west and follows the tail of the escarpment. In the east half of this section the vallum ditch averages 3.5m in depth, while the north and south mounds average 1.5m in height.”

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor linking turrets, milecastles and forts is not yet known with certainty in this section. However, there is a slight rise alongside the field wall on the south side of the wooded area to the south of Carraw Farm which could be the remains of the `agger’, or raised spine, of the road. The antiquarian Horsley, writing in the 1730s, stated that the Military Way was carried on the north mound of the Vallum in this general area.”

Section N (HE:1010959):

“It is visible as a low turf covered causeway immediately south of the car park heading directly for the east gate of the fort, though it fades before it reaches the fort. On the west side of the fort it re-emerges heading from the west gateway to the north mound of the Vallum which was used to carry the road in this section. The road is visible as a low linear mound, 0.2m high, along the summit of the north mound of the Vallum. The Vallum survives as an intermittent earthwork throughout this section.”

“The Military Way survives as a turf covered causeway leading up to the south gateway of the milecastle. Milecastle 31 is situated immediately to the east of Carrawburgh car park with wide views to the north and south, but with a restricted outlook to the east and west. It survives as a low turf covered platform 0.25m high. The remains of north wall of the milecastle lies beneath the B6318 road. Traces of the road connecting the milecastle to the Military Way survive as a causeway 0.15m high. Turret 29b survives as a turf covered mound with parts of the north, west and east walls surviving up to two courses. The road connecting the turret to the Military Way is discernible as a slight linear mound.”

“It was excavated during 1912 by Newbold who found the doorway in the east end of the south side and a ladder platform in the south west corner. Heavily burnt masonry and rubbish indicated that the turret had been destroyed by fire and was then left in ruins. Turret 30a is situated about 400m east of Carrawbrough Farm below the B6318 road. It was located during 1912, though there are no surface remains visible now. Turret 30b is located about 50m west of the drive to Carrawbrough Farm partly below the B6318 road. The south side of the turret is visible in the field to the south of the road as a turf covered scarp, 0.5m high.”

“At Limestone Corner the Military Way is visible as a low causeway, 0.6m high, leading to the south gateway of milecastle 30. Beyond the milecastle it rejoins the north mound of the well preserved Vallum. Excavations during 1911 confirmed this to be the case.”

“There are no upstanding remains of the road to the west of the fort. However, the antiquarian Horsley considered that the Military Way exited Chesters and then converged gradually with the north mound of the Vallum where they continued united for a considerable distance.”

Section O (HE:1010959):

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, survives well in the section between the North Tyne and the fort. The line of the road is clearly defined on the ground leaving the fort by the east gateway and heading towards the Roman bridge. Initially it is a depression and then becomes a causeway with a maximum height of 0.8m with a kerb to the south visible for 1.3m.”

“There are no upstanding remains of the road to the west of the fort. However, the antiquarian Horsley considered that the Military Way exited Chesters and then converged gradually with the north mound of the Vallum where they continued united for a considerable distance”

The reality is that there is no evidence of the Military Way in this section.

Schedule: HE:1018581

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is considered to be on the line of the north mound of the Vallum in this section.”

“Throughout this section the north mound of the Vallum has been largely levelled by ploughing and so it is doubtful whether the Military Way survives intact here. The exception to this is where the angle of descent down to the North Tyne is particularly steep opposite Black Pasture Cottage, and here a turf-covered trackway leaves the line of the north mound to run down the side of a dry valley to rejoin it some 180m further on. This diversion effectively eases the gradient. Where the valley opens out this track is visible as a raised causeway 7m wide and 0.2m high.”

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known for most of this section. It uses the north mound of the Vallum as its base, certainly up to milecastle 25, along which it could be seen by Horsley who recorded it in his 1732 publication. A recent survey by the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England shows that the Military Way probably continued along the north mound of the Vallum beyond milecastle 25 where Horsley could no longer trace it.“

Section O shows us that there is no Military Way as an independent road and only as an assumption of the Northern Bank of the Vallum – which was not continuous in this section due to the River Tyne. Moreover, Section P to W have the same excuse for the loss of the Military Way, a total of 35km (28%) of the wall length. “The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known for most of this section. It uses the north mound of the Vallum as its base.“

Conclusion

Our investigation has found that over 50% of Military Way does not exist as a separate road as suggested by archaeologists and English Heritage. Instead, the existing road is fragmented and only comes ‘alive’ as an independent road when the Vallum separates from the wall at any great distance.

This gives us a clue to the function of the rough and wonky road (known as the Military Way), as the stone for the wall would have needed to be delivered by cart if the Vallum was not available.

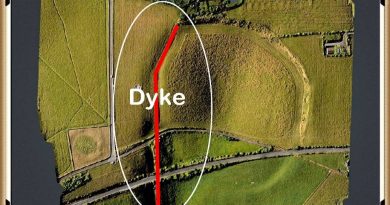

This supports our hypothesis that the Vallum was constructed upon a series of older prehistoric Dykes (canals) and was utilised to carry stone (by boat) to the wall throughout its entire length in association with the ‘Military Way’ for areas of the wall that was too far away from the Vallum for the stone to be easily transported on the Canal.

Moreover, Silbury Avenue was now redundant, and so they moved the large avenue sarsen stones from on top of the hill down to the east side and created West Kennet Avenue as we see today – with the ‘zig-zag’ kink and path correction as you enter Avebury.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

To understand why rivers were larger in the past we have video with all the relevant information.