Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 1.1 The Failure of the “Preglacial Stripe” Hypothesis

- 1.2 LiDAR Evidence: A Road with Edged Ditches

- 1.3 Cart Tracks: The Critical Empirical Evidence

- 1.4 The Avenue Does Not “Wander” to the River

- 1.5 Transport Phases: Bluestones First, Sarsens Last

- 1.6 The Avenue Mounds: Unloading Platforms

- 1.7 Ditches, Water, and Engineering Logic

- 1.8 Conclusion: Britain’s First Engineered Road

- 2 2026 – Update Freshwater Shells, Alluvium, and the End of the “Dry Stonehenge” Myth

- 2.1 Freshwater shells do not lie

- 2.2 Why this matters more than any single borehole

- 2.3 The missing piece: alluvium finally acknowledged

- 2.4 Why periodic flooding without a river does not work

- 2.5 What this means for Stonehenge itself

- 2.6 The Avenue re-interpreted

- 2.7 Where this now leaves the evidence

- 2.8 Final point (and this matters)

- 2.9 Stonehenge as a Hydrological Case Study

- 3 Podcast

- 4 Author’s Biography

- 5 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 6 Further Reading

- 7 Other Blogs

Introduction

Traditional archaeology has long struggled to explain the function of the Stonehenge Avenue. As a result, it has been variously described as ceremonial, symbolic, or a natural feature later adopted by monument builders. None of these explanations withstands close scrutiny once the physical evidence is examined in full.

The Avenue is not symbolic.

It is not accidental.

And it is not ceremonial by default.

It is an engineered roadway.

The Failure of the “Preglacial Stripe” Hypothesis

Traditional archaeologists argue that the Avenue pre-dates Stonehenge as a natural feature. Excavations revealed what were described as “preglacial stripes”, interpreted as frost-thaw features formed during tundra conditions at the end of the last Ice Age. According to this view, Stonehenge was placed here because of these stripes.

This explanation collapses immediately under spatial logic.

The so-called stripes appear only within a narrow corridor approximately twenty feet wide, following the exact line of the Avenue. They do not occur across the surrounding landscape, despite identical geology. The chalk bedrock in this area is uniform and widespread. If these stripes were natural periglacial features, they would appear everywhere — not confined to a single linear path.

Their confinement to the Avenue is decisive.

They are not geological.

They are anthropogenic.

LiDAR Evidence: A Road with Edged Ditches

LiDAR removes vegetation and modern disturbance, revealing the Avenue with clarity. What appears is unmistakable:

• a raised linear surface

• flanked by parallel ditches

• consistent width

• controlled gradient

This is not erosion.

This is not chance.

It is a constructed roadway with drainage.

Changing colour palettes on the LiDAR further enhances internal detail, showing wear patterns within the Avenue itself. Excavation confirms what the remote sensing suggests.

Cart Tracks: The Critical Empirical Evidence

Within the Avenue, excavations have revealed wheel ruts — the most overlooked and most important evidence associated with the site.

Some of these ruts are shallow and relatively light. These are consistent with later historic traffic: carts and carriages weighing approximately 1,500 to 1,800 pounds, around 0.8 tonnes. These tracks align with use recorded in historic drawings, including those made by William Stukeley in the eighteenth century.

But beneath them are far deeper cuts.

These cannot be produced by light vehicles. They require extreme axle loads and slow movement — exactly what would be expected from heavy wheeled transport used to move 25-tonne sarsen stones during the Neolithic.

These deep ruts were misidentified as natural stripes only because their true mechanical origin was never considered.

They are not frost scars.

They are load scars.

Once recognised as such, the Avenue’s function becomes unavoidable.

The Avenue Does Not “Wander” to the River

Conventional interpretations claim that the Avenue takes a long, ceremonial walk down to the present course of the River Avon, passing the so-called King Barrows on the opposite ridge.

This idea is based on modern footpaths and later OS mapping, not archaeology.

Early Ordnance Survey maps do not show this route.

Nor does the physical ground support it.

At the end of the Avenue, the valley floor opens and appears to split — exactly as shown in Stukeley’s eighteenth-century drawings. However, the shallow later tracks here are insignificant when compared to the deeply engineered cut of the original Avenue.

The Avenue originally terminated at the Neolithic shoreline, not the modern river course.

Transport Phases: Bluestones First, Sarsens Last

The Avenue was used over thousands of years, adapting to a retreating shoreline.

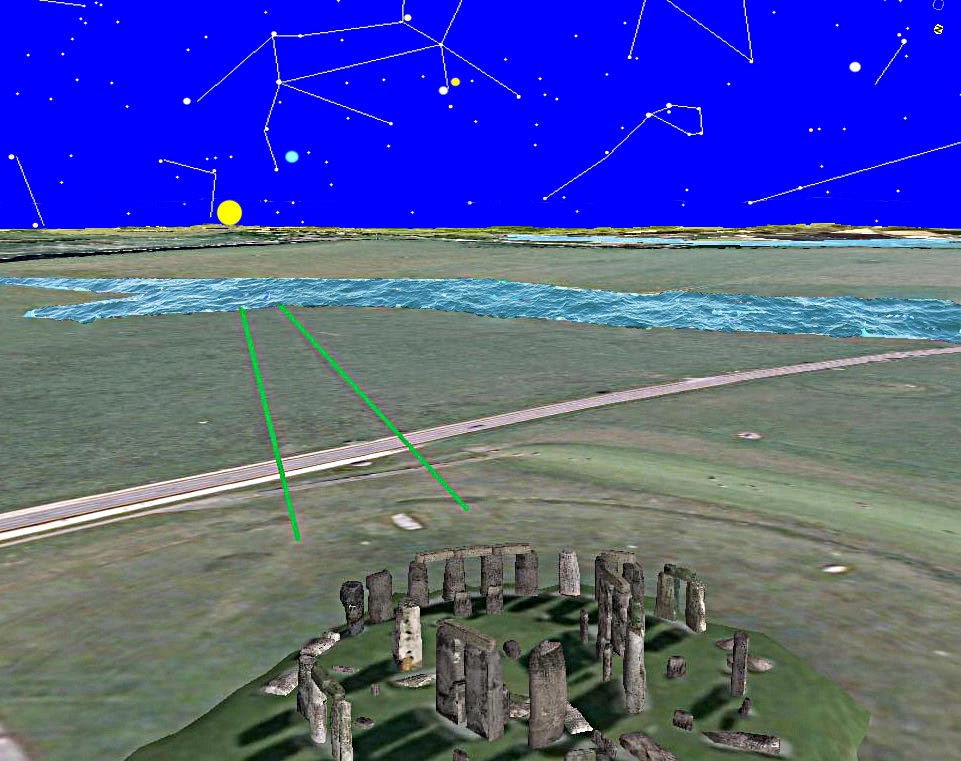

In its earliest phase, during the Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic, it functioned as a water-edge access route, bringing bluestones inland from the west. The angled post holes along the Avenue cannot serve any practical purpose other than mooring posts, aligned deliberately to changing shorelines — a pattern also seen in the former Stonehenge car park excavations.

Later, as water levels dropped, the Avenue was extended and reinforced to support heavy overland transport, culminating in the movement of the sarsen stones from the valley floor up to the monument.

The deepest cart ruts belong to this final phase.

The Avenue Mounds: Unloading Platforms

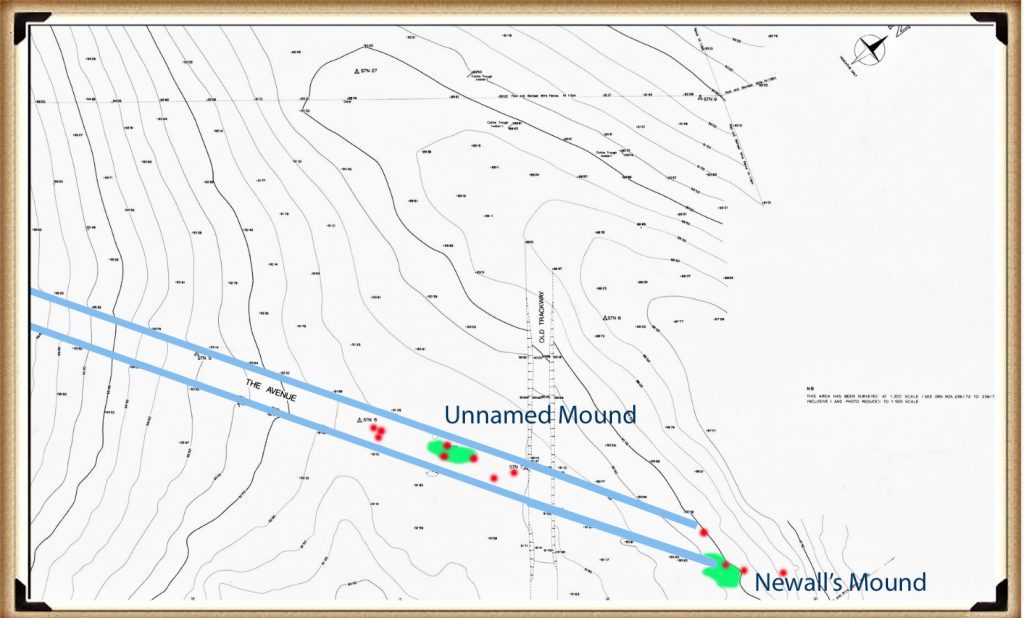

Within the Avenue are two artificial flint mounds.

One is known as Newall’s Mount.

The other remains unnamed.

These mounds have no defensive, ceremonial, or symbolic explanation. They are too low, too functional, and too precisely located.

Their purpose is obvious: raised unloading platforms for boats operating on the Neolithic River Avon. Identical features exist at Avebury and Silbury, forming a repeated architectural solution to the same logistical problem.

Ditches, Water, and Engineering Logic

The Avenue incorporates deliberate water management.

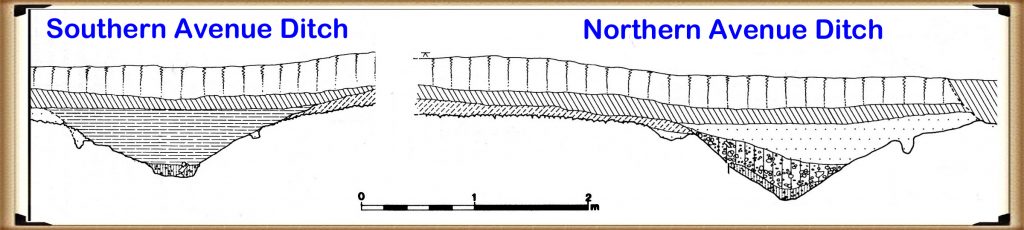

The southern ditch is shallower because the river lies on that side and water access is immediate.

The northern ditch is approximately 10% deeper, compensating for distance from the water source.

This exact asymmetry is repeated at Stonehenge itself, where the north-western sector of the main ditch is also deeper.

This is not ritual.

It is hydraulic calibration.

Conclusion: Britain’s First Engineered Road

The Stonehenge Avenue is not ceremonial by default.

It is not natural.

And it is not symbolic guesswork.

It is Britain’s earliest engineered road — designed first for boats, then for carts, and finally for the heaviest loads ever moved in prehistoric Britain.

The cart tracks prove it.

The LiDAR confirms it.

The hydrology explains it.

Everything else is narrative, built to avoid confronting what the ground itself is saying.

2026 – Update Freshwater Shells, Alluvium, and the End of the “Dry Stonehenge” Myth

In our previous article, Stonehenge Was Flooded: What the Boreholes Actually Show, we demonstrated that subsurface data beneath and immediately around Stonehenge is incompatible with a dry chalk environment throughout the Holocene.

That article focused on borehole stratigraphy: gravels, sands, voids, reworked flint, and repeated water-sorted horizons occurring well below topsoil.

This follow-up adds what can only be described as a smoking gun.

Freshwater shells.

Not found in trenches.

Not found in ritual contexts.

Not explained away as surface contamination.

But found sealed within borehole sequences, at elevations that only make sense if Stonehenge was once hydraulically connected to a river system.

Freshwater shells do not lie

The graphic above plots three boreholes against terrace height and modern groundwater level. What immediately stands out is not just the presence of freshwater shells, but where they occur:

- at multiple depths

- across more than one borehole

- within water-sorted deposits

- well below any plausible archaeological horizon

Shells behave differently from flint.

Flint can be dismissed as “residual”.

Shells cannot.

Freshwater shells do not form in dry chalk, they are not produced by springs, and they are not carried downslope by soil creep. Their only viable mode of emplacement is transport and deposition by flowing water within an active fluvial system.

That is basic hydrology.

Why this matters more than any single borehole

On their own, boreholes showing gravels or sands are often waved away as local anomalies. Archaeology has done this for decades.

But once freshwater shells are present, that escape route closes.

Shells require:

- sustained aquatic habitat upstream

- lateral transport

- deposition within a water-moving system

In other words:

If freshwater shells exist beneath Stonehenge, Stonehenge was not hydrologically isolated.

It must have been connected — directly or seasonally — to the River Avon system.

There is no third option.

The missing piece: alluvium finally acknowledged

This is where the newly cited report becomes critical.

For decades, the claim that “Stonehenge bottom was dry in the Holocene” rested on one assumption:

that no fluvial deposits existed in the surrounding landscape.

That assumption is now demonstrably false.

The Winterbourne Stoke East Archaeological Evaluation Report explicitly identifies:

- alluvium in the valley bottom

- floodplain deposits

- Holocene sediment movement by water

- buried soils and palaeochannel features

You can read the report directly here:![]() https://wessexarchaeologylibrary.org/library/repository/object/160/download/179/

https://wessexarchaeologylibrary.org/library/repository/object/160/download/179/

This matters because alluvium has a precise meaning. It is not “wet ground”. It is not slopewash. It is not groundwater seepage.

Alluvium is river-deposited sediment.

So we now have, independently:

- alluvium proving river activity in the landscape

- boreholes proving water-sorted material beneath Stonehenge

- freshwater shells prove aquatic transport and deposition

That combination is devastating to the dry-chalk model.

Why periodic flooding without a river does not work

A common fallback argument is “periodic flooding”.

But flooding from what?

Springs do not create alluvium.

Rainfall does not sort shells into subsurface layers.

Groundwater rise does not transport sediment laterally.

Flooding only exists because a river overtops its banks.

Once alluvium is acknowledged — as this report now does — a river is no longer optional. It is required.

What this means for Stonehenge itself

Taken together, the evidence now shows:

- Stonehenge sits at a terrace height consistent with fluvial influence

- The monument bottom lies within a former wet basin

- Subsurface deposits show repeated water movement

- Freshwater shells confirm aquatic transport

- The surrounding landscape contains floodplain alluvium

The conclusion is no longer radical, it is simply logical:

Stonehenge was once surrounded by water, and functioned within a river-connected landscape.

That has direct consequences for how the stones arrived.

The Avenue re-interpreted

If Stonehenge was hydraulically connected to the Avon system, then The Avenue stops being a ceremonial path and becomes something far more practical:

A managed water-linked route between river and monument.

Moving multi-ton stones by water is trivial compared to dragging them across dry chalk.

Every ancient riverine culture understood this.

Britain was no exception.

Where this now leaves the evidence

We are no longer talking about one or two anomalies.

Across more than 200 logged samples from Stonehenge bottom, we now have:

- gravels

- sands

- voids

- reworked flint

- freshwater shells

- floodplain alluvium

- palaeochannel indicators

All pointing the same way.

Not ritual.

Not symbolism.

Hydrology.

Final point (and this matters)

The idea that Stonehenge stood isolated on dry chalk throughout the Holocene was never proven.

It was assumed.

That assumption no longer survives contact with the data.

Freshwater shells are the smoking gun — and the alluvium has finally been acknowledged.

The landscape was wet.

The monument was connected.

And water, not land, explains how Stonehenge worked — and how it was built.

The Prehistoric AI Team ![]()

NB: The first graphic shows two boreholes placed at the margins of the Stonehenge basin, where freshwater shells would be expected if the monument once lay on a river shoreline. Shells occur at these edges and are absent from the centre until around 66.60 m OD, where the former channel reaches the basin floor. This is the same infilling pattern seen at Avebury, where a once-open river course has been choked by sediment from surrounding higher ground over the last ~5,000 years. With the present groundwater table at 75 m OD, the system remains hydraulically live; remove the infill and the river would flow again. The evidence is now unequivocal. The second is from the official A303 Tunnel report showing how shallow is the water table to the bottom of the ditch.

In-depth at certain points. The presence of this trench suggests a purpose beyond the ceremonial, indicating either practical or symbolic significance. While there is no direct evidence of a connection between the ditch and the existing moat, it becomes unnecessary given the porous nature of chalk, which allows water to flow over short distances.

Stonehenge as a Hydrological Case Study

Stonehenge occupies a low-lying basin within a chalk landscape that functions as a regionally connected aquifer rather than a dry, impermeable surface. Chalk terrains absorb rainfall, transmit groundwater laterally over wide areas, and express excess water through rivers and wetlands at topographic lows. In post-glacial conditions—characterised by high recharge, limited vegetation, and reduced evapotranspiration—groundwater tables would have been substantially higher than today. Under such conditions, river systems expand laterally, valley floors remain saturated, and shallow basins become hydraulically active components of the wider fluvial network (British Geological Survey, British Upper Cretaceous Stratigraphy; Wessex Archaeology, Winterbourne Stoke East Archaeological Evaluation Report). From a physical standpoint, hydrological connectivity is therefore the expected condition, not an exception.

At Stonehenge, this expectation is reinforced by independent subsurface and engineering evidence. Borehole records around the monument document water-sorted sediments and freshwater shells at depth, while landscape investigations identify alluvium and floodplain deposits within adjacent valleys (Wessex Archaeology, Winterbourne Stoke East Archaeological Evaluation Report). Crucially, tunnel ground-investigation cross-sections prepared for the A303 scheme show Stonehenge Bottom as a structurally controlled groundwater basin, with measured groundwater levels intersecting the basin floor and permeability contrasts forcing hydraulic convergence (Highways England, Implications of 2018 Ground Investigations to the Groundwater Risk Assessment, REP3-019; reproduced in Stonehenge Alliance, Written Summaries of Oral Submissions at ISH10). These data demonstrate that Stonehenge was not hydrologically isolated but formed part of a river-connected landscape linked to the River Avon system. When viewed in this context, the Avenue resolves as a water-aligned route rather than a purely ceremonial path, and stone transport by water becomes a practical consequence of post-glacial chalk hydrology rather than a speculative alternative.

More information on Stonehenge Avenue can be found on our documentary video: https://youtu.be/-Ds1HYB15w8

Podcast

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?