The Roman Military Way Hoax

Promotional Video – Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – The Vallum (Roman Military Way)

Extract From Book……………………… Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – The Vallum

Contents

Introduction

This blog post challenges traditional interpretations of the Vallum and associated Roman infrastructure near Hadrian’s Wall. It posits that the Vallum may have originated as a prehistoric canal system, later repurposed by the Romans. The article critiques the conventional view of the Military Way as a continuous Roman road, highlighting its fragmented nature and inconsistent construction. Additionally, it questions the existence and connectivity of the Stanegate road, suggesting that many forts lack direct road links and may have relied on river transport instead. The piece advocates for a reevaluation of these structures, considering them as part of a complex, multi-period landscape rather than solely Roman military installations.(The Roman Military Way Hoax)

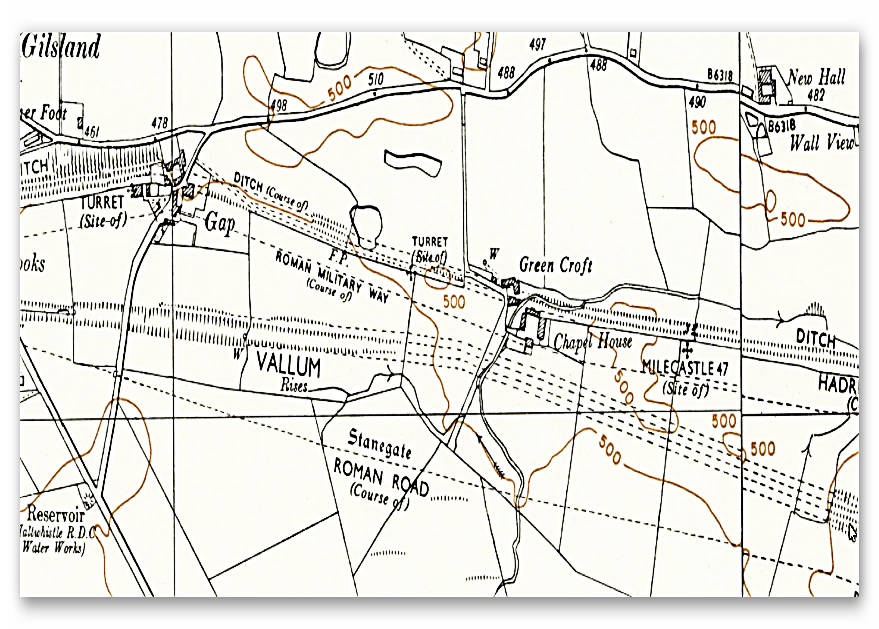

Traditional archaeologists and archaeological establishments like English Heritage suggest that:

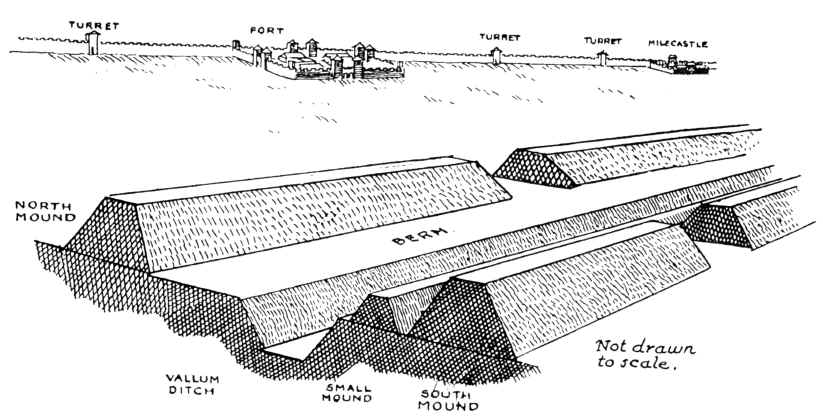

The Vallum is a massive earthwork constructed shortly after Hadrian’s Wall itself and lying just south of it. Many visitors confuse the Vallum with Hadrian’s Wall itself because it’s such an obvious and impressive feature in the landscape.

In fact, the Vallum is made up of several different elements – a ditch around 6 metres wide and 3 metres deep; two mounds either side of the ditch about 6 metres wide and 2 metres high and set back from the ditch by around 9 metres; and often a third mound on the southern edge of the ditch. The whole complex is around 36 metres across. Usually, the Vallum runs close behind the Wall but in the rocky and hilly central section the Vallum lies up to 700 metres from the Wall.

Crossing points seem to have been located south of each of the forts along Hadrian’s Wall and near several of the milecastles. Evidence from the excavated Vallum crossing at Benwell in Newcastle shows these crossing points had impressive monumental gateways.

The Vallum’s purpose is unclear. Many archaeologists think it marks the southern boundary of a military zone with the Wall itself forming the northern boundary. This would have helped protect the rear of the Wall and its associated military installations, with civilian access being closely controlled. The gateway at Benwell supports this idea. The numerous gateways along the Wall at forts and milecastles suggest that the frontier was intended as much to control movement as to provide a defensive line. Traders would have moved goods across the frontier but their movements would have been controlled and their goods taxed.

Relatively soon after it was constructed, some 20 to 30 years perhaps, the Vallum seems to have lost its function – the mounds were cut through and the ditch filled in at fairly regular intervals. It was out of use by the time the forts along the Wall were re-commissioned in the late second century AD following the return of the garrison from the Antonine Wall.

Sadly, these ideas that have been constructed over the last 200 years are somewhat questionable. Within the book we look at associated aspects of this area like Military Way which was supposed to be constructed to patrol the so-called ‘Military Zone’ – to find that:

That over 50% of Military Way does not exist as a separate road, as described by archaeologists. Instead, the perceived road is fragmented and only becomes ‘alive’ as an independent road when the Vallum separates from the wall at any distance.

This might give us a clue to the function of this rough and wonky road, as the stone for the wall would have needed to be delivered by cart if the Vallum canal was not available.

As for the Stanegate that was supposed to connect to the main forts in the area as a ‘defensive shield’ we actual found that it is very little to no evidence of the ‘Stanegate Roman Road’, which (according to the current theory proposed by English Heritage) ‘consolidated as a frontier’ during the late first and early second century AD and helped crystallise Roman tactics and military expectations in the area.

This evidence is compounded when you release that of the 80mile border from coast to coast – Stonegate, at best, covers just 38.1 miles (47%) of the ‘defensive gap’, and hence suggestions of extension over and above the existing line existed (even without support from OS maps). Moreover, the research has shown the ‘raw’ Stanegate road without the ‘hidden’ parts below the B-roads – we are only looking at 20% of the declared road being visible on LiDAR maps.

Stanegate Road (when not part of an existing B-road system) is inconsistent in width and structure -moving from bank track to road with two ditches on each side to a ditch with two banks far from straight and usually starts and ends in ravens.

Most Forts and the Stanegate are not found to connect (with intersecting sub-roads) on only two occasions, and the rest show no connection. Moreover, later ‘temporary’ camps also did not connect with the road – which questions whether (a defence line) was its purpose.

Moreover, this would then question the ‘myth’ of using the Stanegate as a ‘boundary’ for withdrawing troops from Scotland in the first century AD is correct. And whether the River Tyne (which most of these Forts sit upon) was used as a more practical and effective boundary/defence.

This ‘myth buster’ will not surprise many in academia as it has been ‘hinted’ at for some time (but not acted upon it by updating the literature), as we see from Symonds et al.

“The question of whether a road even existed when the fortlets were founded is by default an existential one for the notion that they provided highway protection. But even if the metalled road does post-date the fortlets, a reasonably robust thoroughfare of some form must have existed from at least the mid AD 80s to service Vindolanda. The question is not whether there was a road, but whether it was metalled when the fortlets were founded.” Symonds, M. (2017). Hadrian’s Wall. In Protecting the Roman Empire: Fortlets, Frontiers, and the Quest for Post-Conquest Security (pp. 95-132)

Moreover, even if Stanegate was not built as suggested, it exists in parts, and it looks prehistoric (by design) as it relies heavily on ravens that start and end sections of the Stanegate sections; its sunken structure in parts is unfamiliar to traditional Roman Road design.

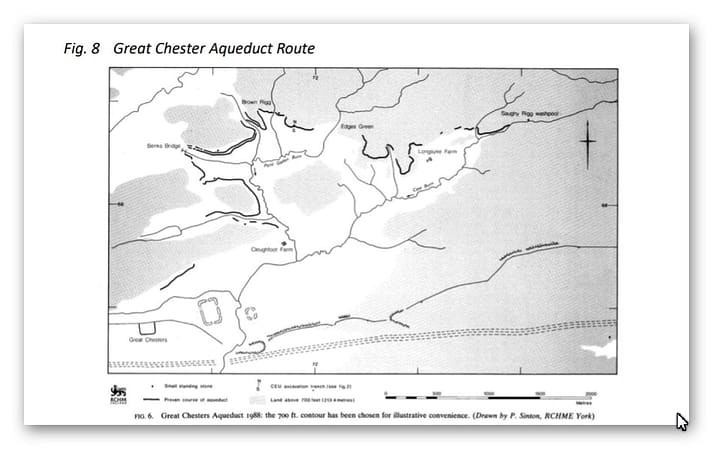

As for other famous ‘Roman Features Such as the Great Chesters Aqueduct, again we find not only is the origin questionable but as it located supposedly fully in ‘hostile territory – they its usefulness win conflict would be limited.

It is clear from the LiDAR research that the suspected Roman Aqueduct is not as it seems. This is not the first examination to spread doubt about the scale and origin of this feature in the landscape – MacKay, D. A. (1990). The Great Chesters Aqueduct: A New Survey. Britannia, 21, 285–289. Also shows an incomplete map of this aqueduct.

Mackey failed to find in their survey that the Aqueduct changed size, and the path suggested had no identifiable remains of the bridges required to make this Aqueduct work.

Our more detailed findings indicate that the topology of the aqueduct suggests that it would need to go uphill at several points without any powered assistance (like a siphon) and so is mechanically unsound. Our finding has found that the use of ‘Dykes’ in this area and some connecting to this Aqueduct feature is new. We have also shown that closer to the Fort it was supposed to supply, there were closed water sources which could be used and that the Fosse by the Wall was also a water supply.

We conclude that we found a prehistoric watercourse linked to their sophisticated ‘Dyke’ system. I would be bold to suggest that this was used for either agricultural purposes or maybe industrial, seeing the multiple sites of quarries associated and in the region of this feature.

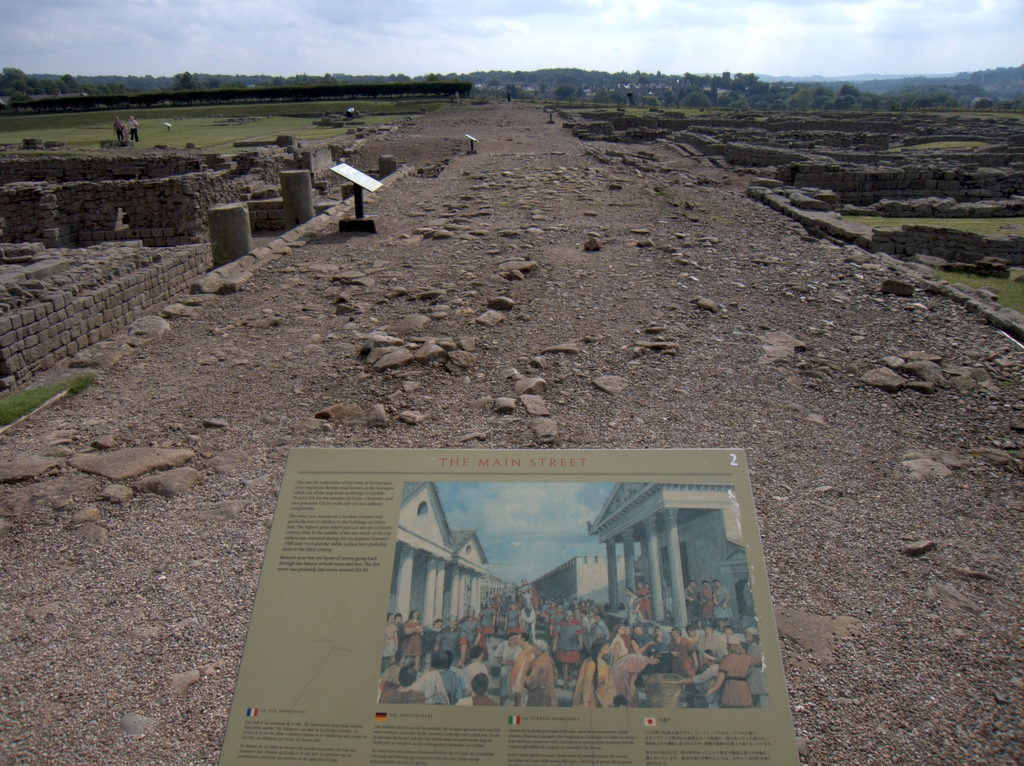

Case Study – The Roman Military Way

Many, new to the famous Whin Sill section of the Roman Wall frontier, confuse the Military Road (B6318) with the Roman Military Way. They have nothing in common either in time or purpose; in fact, the Military Road was only constructed after the Jacobite Rising of 1745, mainly upon the ruin of the wall!

The Romans created the Military Way (according to Historic England) to relay goods speedily along the line of the Wall. It was used to support the running of the frontier wall during the Roman period.

When Hadrian’s first grand plan was executed, The Stanegate (another Case Study in this book) was created as an east/west military road. But when Hadrian’s successor, Antonius Pius, pushed the frontier north through the isthmus between the Forth and Clyde, creating the Antonine Wall (yet another case study in this book), the supply road was installed integral to the turf-banked frontier linking the forts and milecastles.

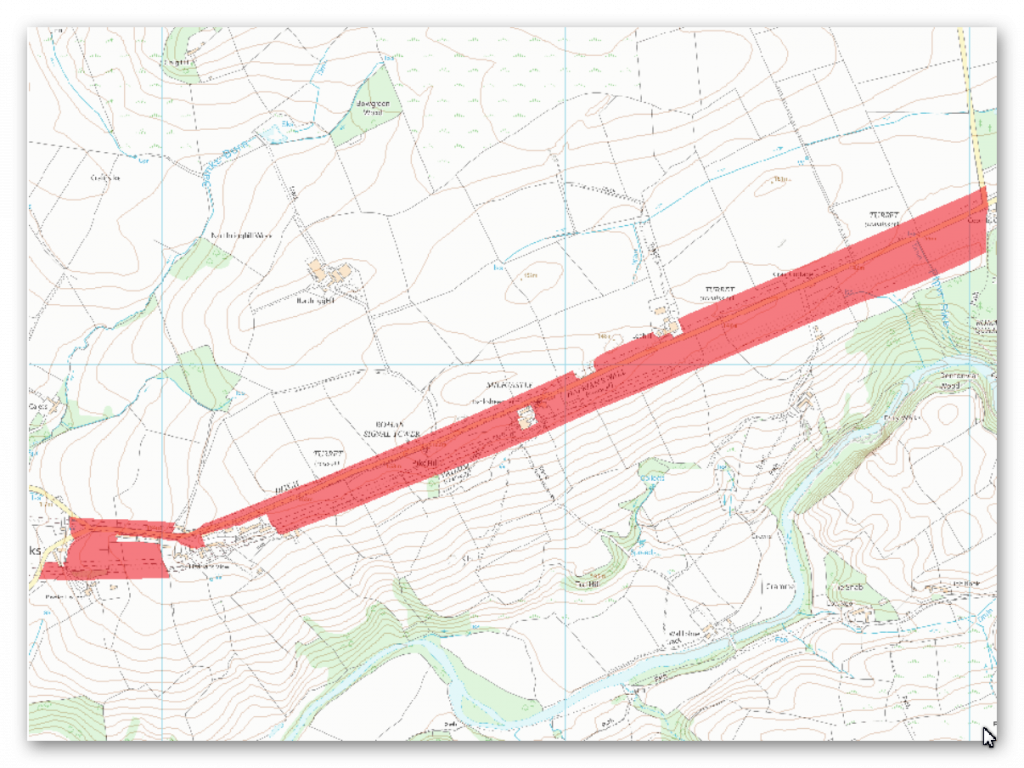

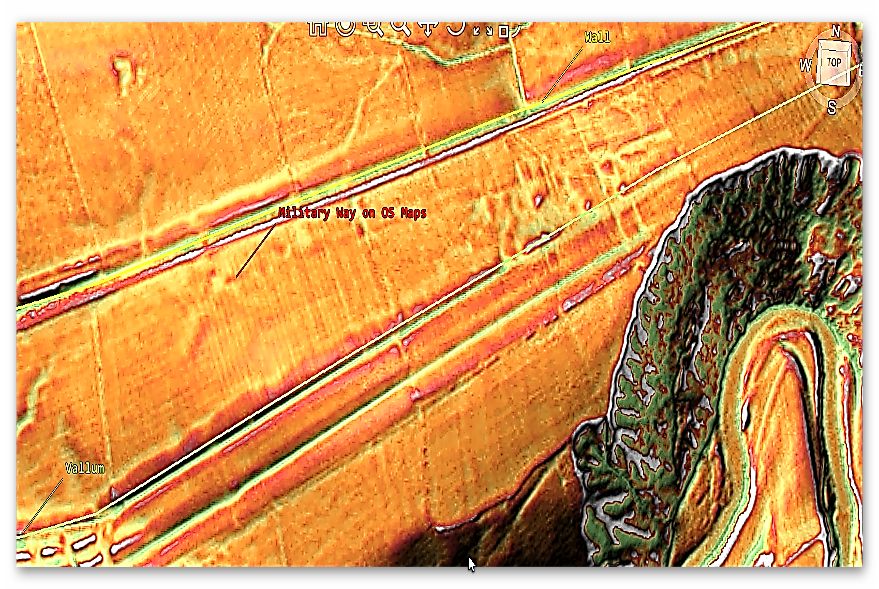

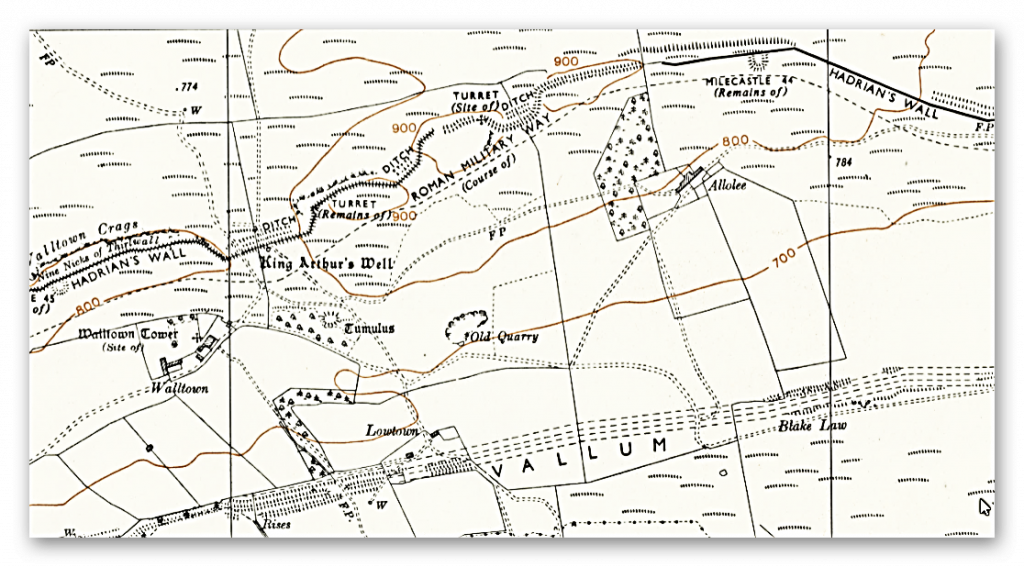

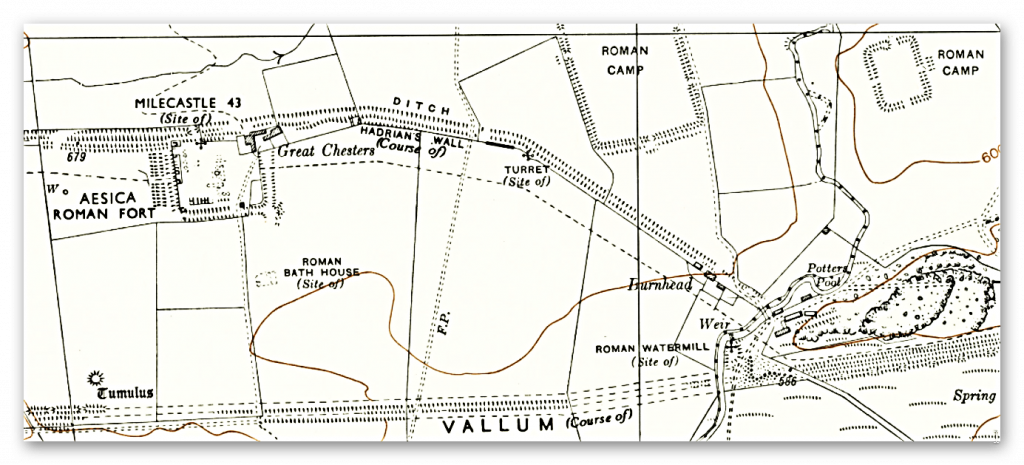

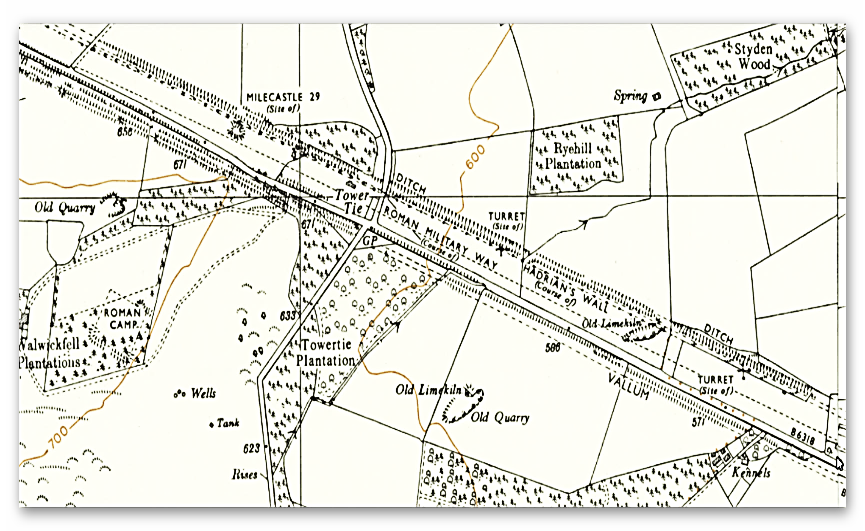

Figure 83- Section H (HE:1010996)

When the frontier retreated to consolidate upon the original Hadrianic line over time, it was essential to have the same flexibility close to Hadrian’s Wall.

But does it exist, and what was it for in reality?

If we look at the first instance of this ‘alleged’ road, we need to go to Section E – schedule Monuments section 1010979, although this is some 24.2 km from the western flank of Hadrian’s Wall – which must ask the question – what was used for that 20% of the wall that is missing?

Yet another mystery occurs when we find this ‘road’ – there is nothing on LiDAR! Further investigation into why HE included it in its report shows that – it probably never existed in the first place.

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has been identified for a short distance to the east of Wallhead.

No remains are visible on the surface except for a short section of a turf-covered mound, 4m-5m wide and up to 0.4m high.

Its course was confirmed during excavation in 1894 by Haverfield. The road consisted of a gravel layer laid over larger stones with a stone kerb and central spine. Its survival here was confirmed by a geophysical survey in 1981. However, the unusual survival of this section suggests the possibility that it was reused in the medieval period serving as access to Bleatarn Quarry”

It was misidentified over a hundred years ago and was found to be a better quarry road – so the search continues….. So, we now move to Section H (HE 1010996), some 33.5 km from the Western start of the Wall (27.5%) – so what do we have here?

“The exact course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, is known intermittently throughout this section where it survives as an earthwork feature.

Opposite the disused quarry west of Bankshead Farm the Military Way survives as a terrace, 3m-5m wide, on the north side of an old hedge line. Occasional rises in hedgelines denote traces of its course”

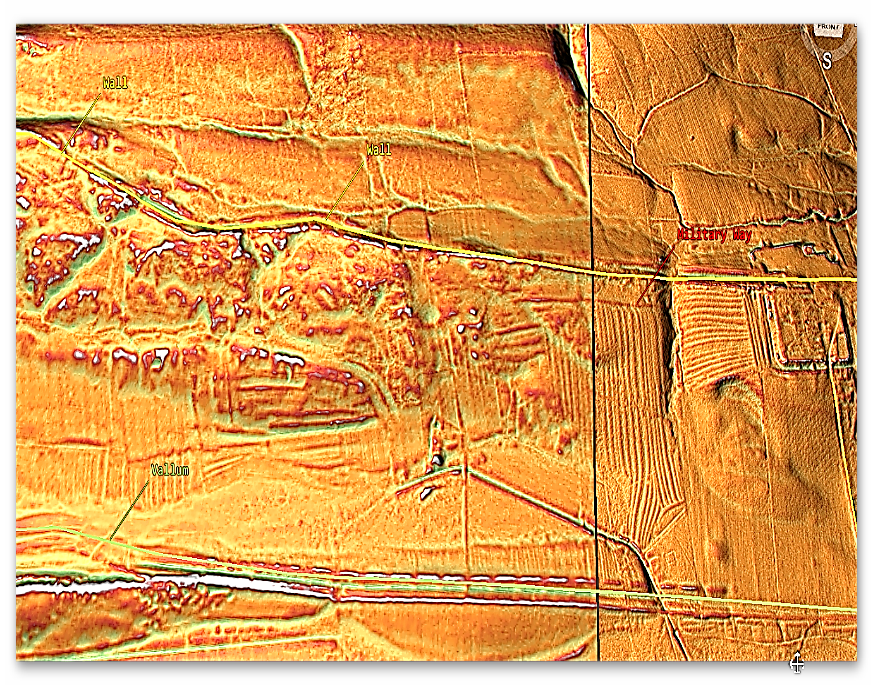

Again, it does not appear on the OS (1800) map, and what we find on the LiDAR maps seems to indicate it is linked to the Old Quarry rather than ‘connecting turrets and milecastles’.

Moreover, the Vallum has disappeared from this section and what we might be seeing is a shallow bank of the Vallum of a replacement.

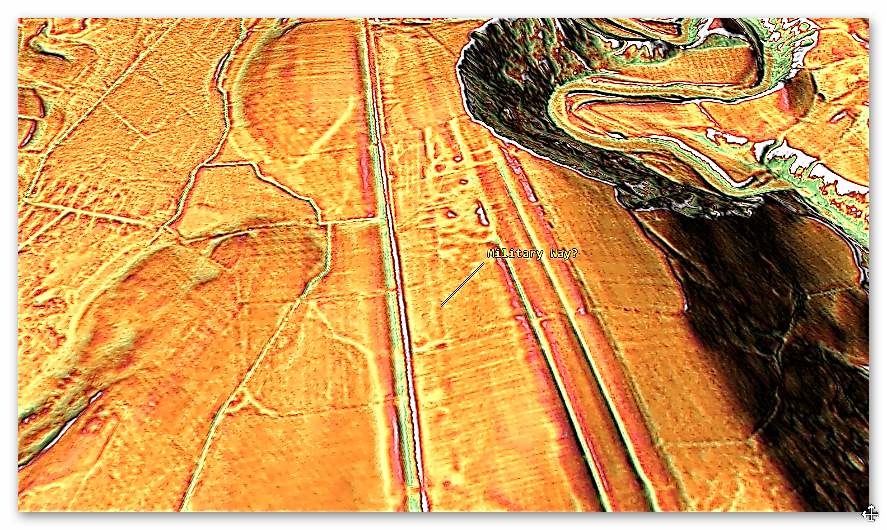

In Section HE: 1010994 (Section I), it is reported that:

Excavations in 1911 by Simpson showed there to be two early floor levels and late pottery, demonstrating that the turret had continued in use, unlike many other turrets. The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known throughout this section. West of the fort, it survives as an intermittent low linear mound, 0.1m in maximum height. East of the fort a geophysical survey in 1986 by Walker confirmed the existence of the Military Way below the turf cover.”

There looks like a partial road in between the Wall and The Vallum. Which may join the Station (Amboglanna) to the Milecastle in that region – but it’s not a connecting road that continues past this isolated point (less than 1000m in length)?

The road disappears for another 7km and then reappears again in Section I on the OS maps.

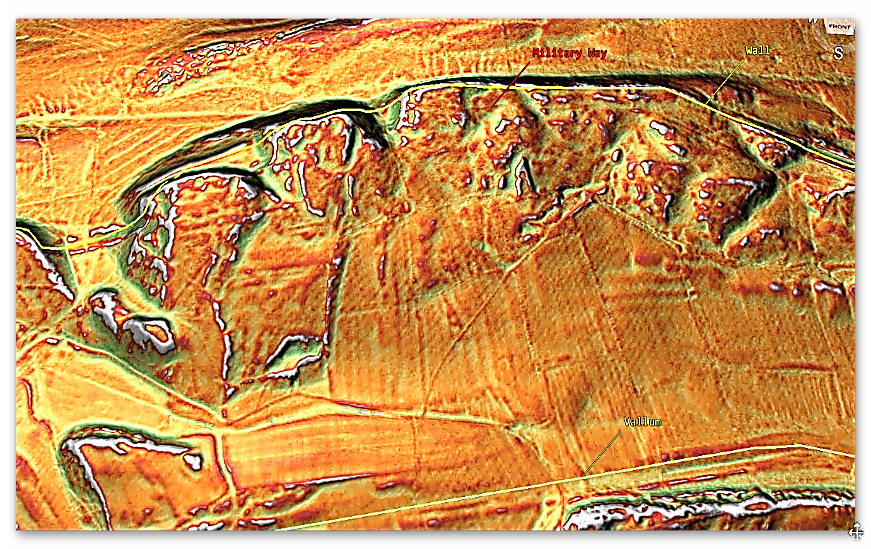

Then it is report in Section J as:

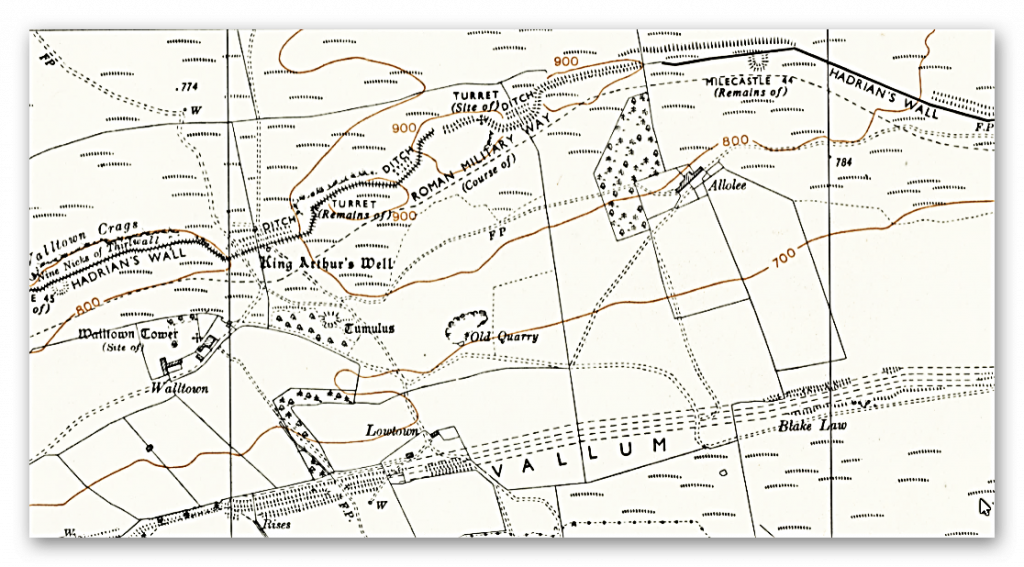

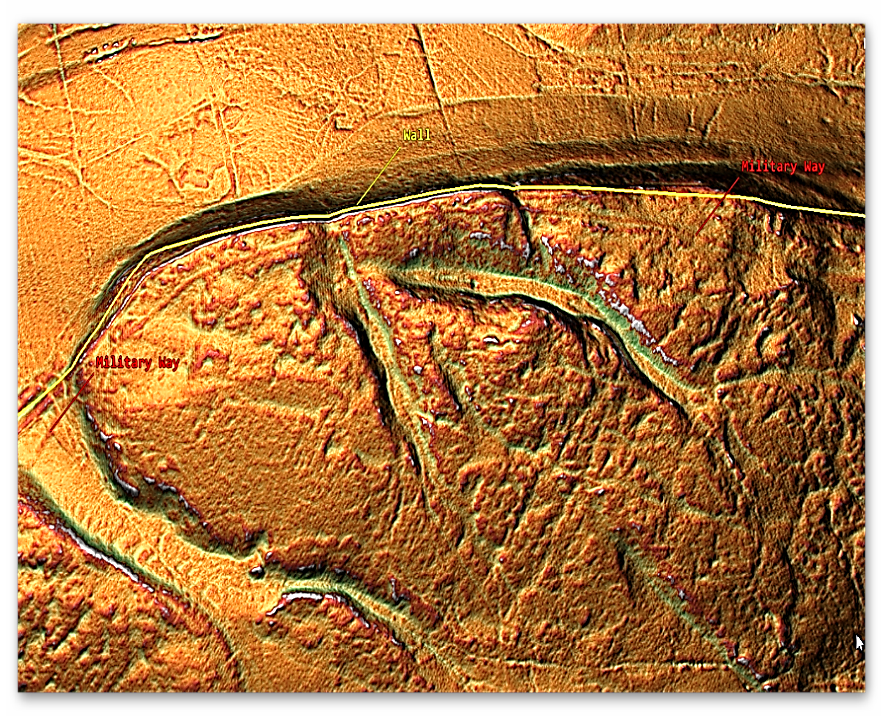

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, is known throughout this section. It is visible as a low causeway, 0.2m high, or as a terrace, 5m wide, winding between rock outcrops to the south of the Wall. Turret 45a is situated on a high point on Walltown Crags with extensive views in all directions. It survives as an upstanding exposed feature, which is consolidated and in the care of the Secretary of State”

“The road which connected the milecastle to the Military Way survives as a causeway 3.5m wide and 0.2m high. Milecastle 45 is situated on the crest of Walltown Crags with commanding views to the north and south.”

“It survives as a low turf covered causeway 5.5m wide and up to 0.5m high, or as a terrace in the hillside with a minimum width of 3m. It is straight for most of its course except where it deviates around rock outcrops.”

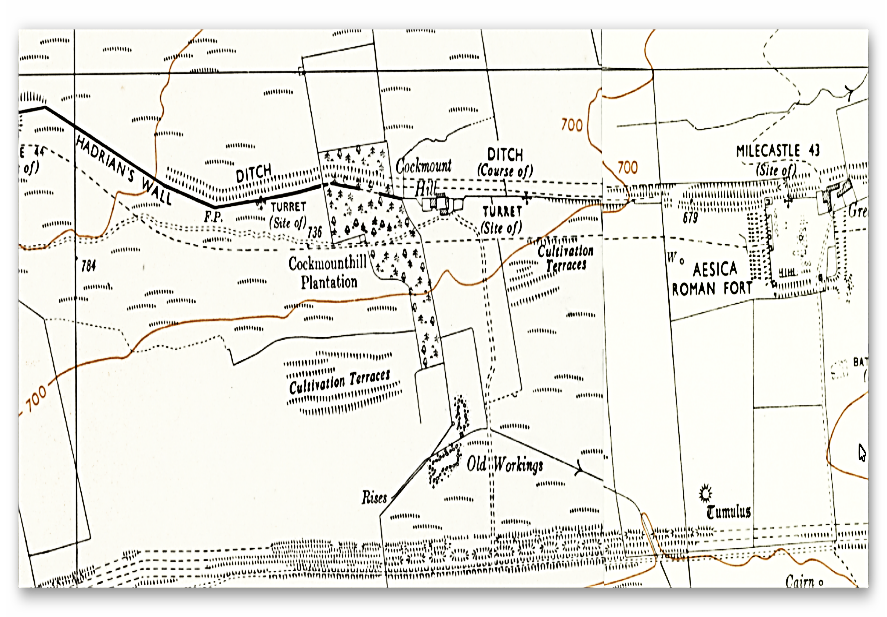

“West of the Cockmount Hill Plantation the foundations of two large regularly laid out rectangular buildings overlie the Military Way, using it as a hard standing. Their form suggests they are post-medieval or later in date. South east of King Arthur’s Well a spur road branched off the Military Way, the remains of which can be seen as a turf covered causeway leading south east towards Lowtown.

“Its course from the Caw Burn is known where it survives as a low turf-covered mound, 6m to 8m wide and 0.2m to 0.5m high. Occasional sections of this low turf-covered causeway reappear on the line up to the east gateway of Great Chesters fort. Beyond the field boundary west of the fort the Military Way is visible again as a discontinuous terrace with a slightly sinuous course which avoids the rock outcrops. Field gates are positioned on its course at the east and west end of this stretch. A road linking the Military Way and the Stanegate Roman road to the south via Great Chesters fort is overlain by the modern trackway to Great Chesters Farm which enters the fort through the south gateway.”

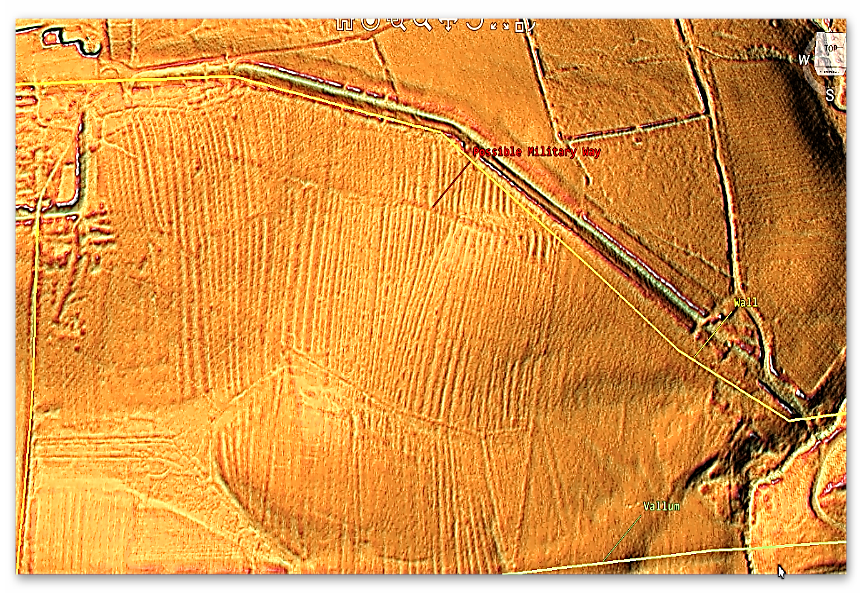

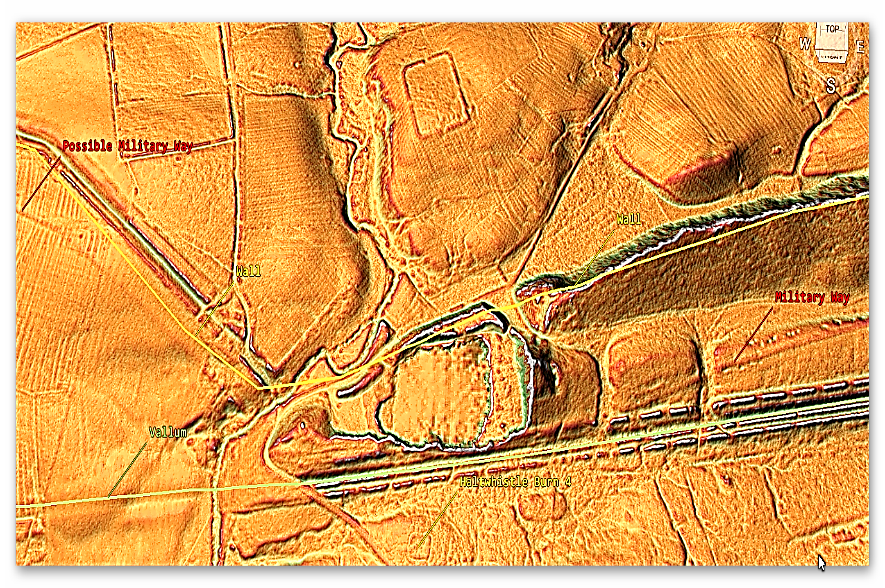

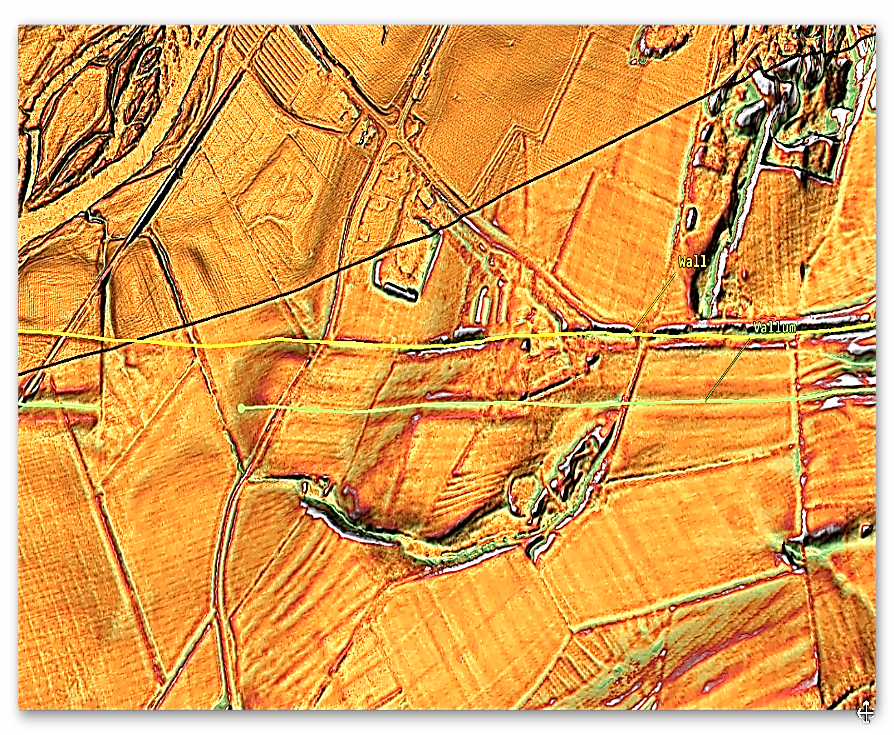

From these strong descriptions, we imagine that the course and evidence for the road will show strongly on LiDAR – but it’s invisible for a small 260m section.

In Section K we find in Schedule HE: 1010975:

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts is known throughout this section except around Cawfields Quarry where its precise course has not yet been confirmed. It survives as a linear causeway which is most prominent at the east end of this section. Here it measures between 3.5m and 5.2m wide with a revetment containing large stones on the south side and with evidence of a stone kerb. Further west the causeway, where extant, averages about 0.1m in height and 7m in width.

Where there is no trace of the causeway the line of the road has been identified by changes in vegetation growth with grass growing less well above the former road surface. Around Cawfields Quarry the remains of the Military Way may have been destroyed by the quarry, however it is possible that here the Military Way was built on the line of the Vallum, as it was further to the east at the crossing site of the Caw Burn and thus survives. About 200m east of milecastle 42 and 10m to the south of the Military Way is a fallen Roman milestone. It measures 1.38m high by 0.4m by 0.3m. It is oblong in shape and crudely rounded at the corners. This uninscribed milestone now lies in long grass. Two other milestones from this vicinity have been removed and are now in Chesters museum.”

The LiDAR map shows that the road did not go to the Quarry but terminated in the River Valley (Like the Vallum) – was there a bridge across (no foundations) shown on the LiDAR map?

Section HE: 1010973 suggest that:

“Its course is marked usually by a slight causeway, up to 0.2m high, or by differing vegetation marks seen in grass colour. This differentiation in vegetation cover reflects differing growing conditions on the compacted road surface. It is best preserved where it crosses a gully running into Green Slack. Here it survives as a built up causeway, 1.7m high and 2m wide. South of milecastle 41 the causeway survives up to 0.7m high with kerb stones on its south side.”

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, survives well as a linear causeway throughout this section. Some stone is visible on the south scarp where it has been built up to make a level surface. This scarp appears to have had a stone revetment. The south scarp averages 0.4m in height, although it reaches up to 1.2m high in places. West of Peel Farm the Military Way is overlain by the road to Steel Rigg car park. To the south of Sycamore Gap are the remains of a prehistoric field boundary running roughly from north to south, probably dating to the Bronze Age.

The Roman Military Way overlies this boundary, indicating that it is certainly pre-Roman in date. The peat bog, which has grown over remains of this boundary further to the south, is of Bronze Age origin. A second boundary is located running transversely to the Sycamore Gap boundary, to the west of it, south of the Military Way. Their assumed junction is masked by the peat bog which has built up to the south.”

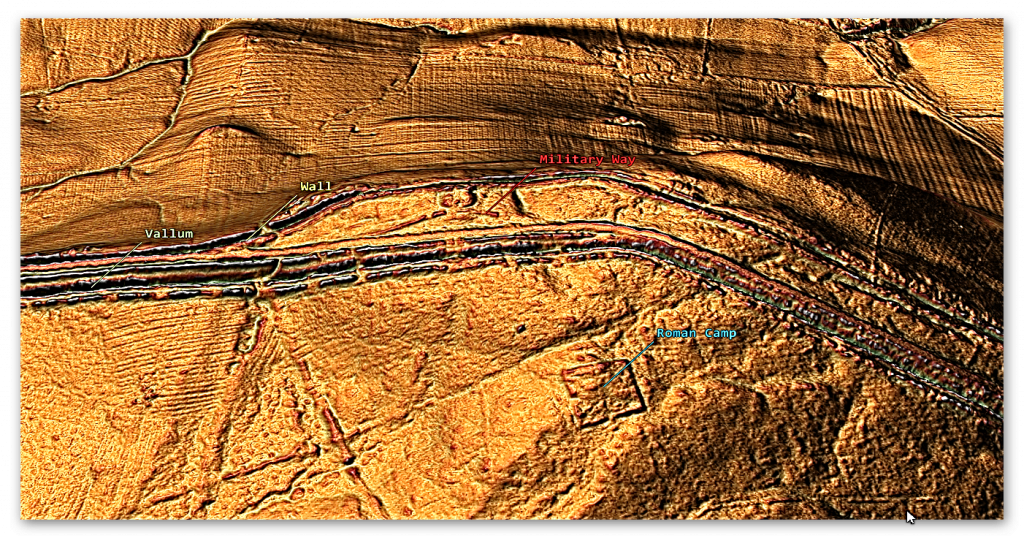

Section L – Schedule HE:1010964:

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts survives as a turf-covered linear mound throughout most of this section. It is visible as a disturbed causeway averaging 5m wide with traces of a stone revetment on the south side. It was partly excavated between 1978 and 1980 when it was shown to have a damaged metalled surface 4m wide, a stone revetment on the south scarp, and to have been overlain by later roadways. Branch roads link the Military Way with the south gates of milecastles 35 and 36. At milecastle 35 the low, uneven turf-covered mound of the causeway is up to 5.5m wide and 0.2m high.”

Section M – Schedule: HE:1010963:

“The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, was carried on the north mound of the Vallum in the east half of this section. Its buried remains survive below grassland east of milecastle 33, until the B6318 road coincides with the north mound of the Vallum where it lies below the modern road surface.

South of turret 33b the Military Way leaves the north mound of the Vallum and follows a course parallel to that of the Wall. Here it survives as a distinct linear mound up to 6m wide and up to 0.3m high. The Vallum survives well as an upstanding earthwork visible on the ground throughout this section. It runs roughly parallel with the line of the Wall until south of turret 33b where it turns to the south west and follows the tail of the escarpment. In the east half of this section the Vallum ditch averages 3.5m in depth, while the north and south mounds average 1.5m in height.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor linking turrets, milecastles and forts is not yet known with certainty in this section. However, there is a slight rise alongside the field wall on the south side of the wooded area to the south of Carraw Farm which could be the remains of the `agger’, or raised spine, of the road. The antiquarian Horsley, writing in the 1730s, stated that the Military Way was carried on the north mound of the Vallum in this general area.”

Section N – Schedule HE:1010959

“It is visible as a low turf covered causeway immediately south of the car park heading directly for the east gate of the fort, though it fades before it reaches the fort. On the west side of the fort it re-emerges heading from the west gateway to the north mound of the Vallum which was used to carry the road in this section. The road is visible as a low linear mound, 0.2m high, along the summit of the north mound of the Vallum. The Vallum survives as an intermittent earthwork throughout this section.

The Military Way survives as a turf-covered causeway leading up to the south gateway of the milecastle. Milecastle 31 is situated immediately to the east of Carrawburgh car park with wide views to the north and south but a restricted outlook to the east and west. It survives as a low turf covered platform 0.25m high. The remains of north wall of the milecastle lies beneath the B6318 road. Traces of the road connecting the milecastle to the Military Way survive as a causeway 0.15m high. Turret 29b survives as a turf-covered mound with parts of the north, west and east walls surviving up to two courses. The road connecting the turret to the Military Way is discernible as a slight linear mound.

It was excavated during 1912 by Newbold who found the doorway in the east end of the south side and a ladder platform in the south west corner. Heavily burnt masonry and rubbish indicated that the turret had been destroyed by fire and was then left in ruins. Turret 30a is situated about 400m east of Carrawbrough Farm below the B6318 road. It was located during 1912, though there are no surface remains visible now. Turret 30b is located about 50m west of the drive to Carrawbrough Farm partly below the B6318 road. The south side of the turret is visible in the field to the south of the road as a turf covered scarp, 0.5m high.

At Limestone Corner the Military Way is visible as a low causeway, 0.6m high, leading to the south gateway of milecastle 30. Beyond the milecastle it rejoins the north mound of the well preserved vallum. Excavations during 1911 confirmed this to be the case.

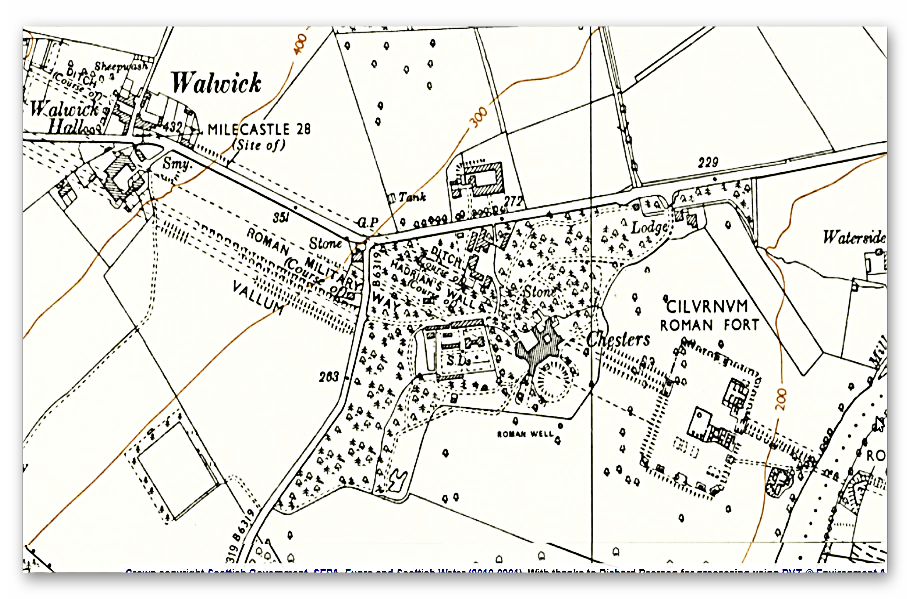

There are no upstanding remains of the road to the west of the fort. However, the antiquarian Horsley considered that the Military Way exited Chesters and then converged gradually with the Vallum’s north mound where they continued to unite for a considerable distance.”

Section O – Schedule HE:1010959

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, survives well in the section between the North Tyne and the fort.

The road line is clearly defined on the ground leaving the fort by the east gateway and heading towards the Roman bridge. Initially, it is a depression and then becomes a causeway with a maximum height of 0.8m with a kerb to the south visible for 1.3m.

There are no upstanding remains of the road to the west of the fort. However, the antiquarian Horsley considered that the Military Way exited Chesters and then converged gradually with the north mound of the Vallum, where they continued united for a considerable distance

Schedule: HE:1018581

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is considered to be on the line of the north mound of the Vallum in this section. Throughout this section the north mound of the Vallum has been largely levelled by ploughing and so it is doubtful whether the Military Way survives intact here. The exception to this is where the angle of descent down to the North Tyne is particularly steep opposite Black Pasture Cottage, and here a turf-covered trackway leaves the line of the north mound to run down the side of a dry valley to rejoin it some 180m further on. This diversion effectively eases the gradient. Where the valley opens, this track is visible as a raised causeway 7m wide and 0.2m high.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known for most of this section. It uses the north mound of the Vallum as its base, certainly up to milecastle 25, along which it could be seen by Horsley who recorded it in his 1732 publication. A recent survey by the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England shows that the Military Way probably continued along the north mound of the Vallum beyond milecastle 25, where Horsley could no longer trace it.

Section O shows us that there is no Military Way as an independent road and only as an assumption of the Northern Bank of the Vallum – which was not continuous in this section due to the River Tyne.

Sections P to W have the same excuse for the loss of the Military Way, a total of 35km (28%) of the wall length.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known for most of this section. It uses the north mound of the Vallum as its base.

Conclusion

Our investigation has found that over 50% of Military Way does not exist as a separate road, as described by archaeologists. Instead, the perceived road is fragmented and only becomes ‘alive’ as an independent road when the Vallum separates from the wall at any distance.

This might give us a clue to the function of this rough and wonky road, as the stone for the wall would have needed to be delivered by cart if the Vallum canal was not available.

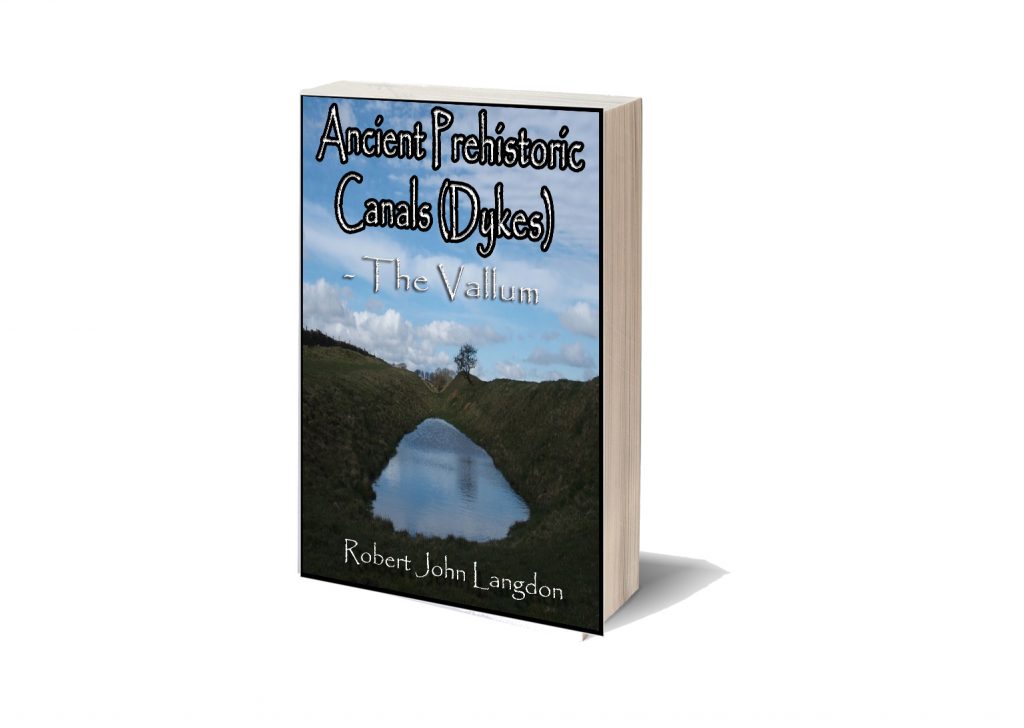

This was an extracts from the NEW Book Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke available on Amazon as a FULL COLOUR HARD BACK (£49.95) or a ECONOMY (£9.99) SOFTBACK black and white VERSION – it is also available as a KINDLE (£2.99) book. For further information about our work on Prehistoric Britain visit our WEBSITE or VIDEO CHANNEL.

Product details

- ASIN : B0BN7PD6BS

- Publisher : Independently published (24 Nov. 2022)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 477 pages

- ISBN-13 : 979-8358524187

- Dimensions : 15.24 x 3.33 x 22.86 cm

- Illustrations: 350+

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

(Maritime Diffusion Model for Megaliths in Europe)

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?