The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

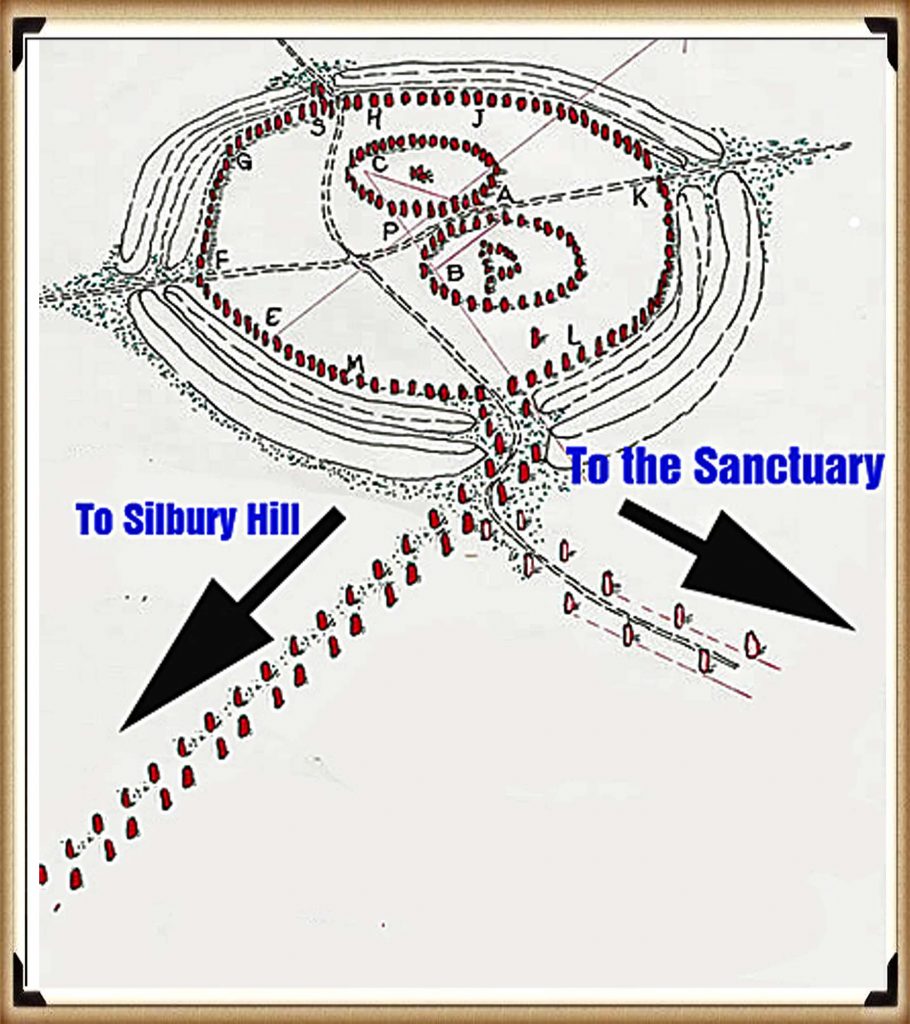

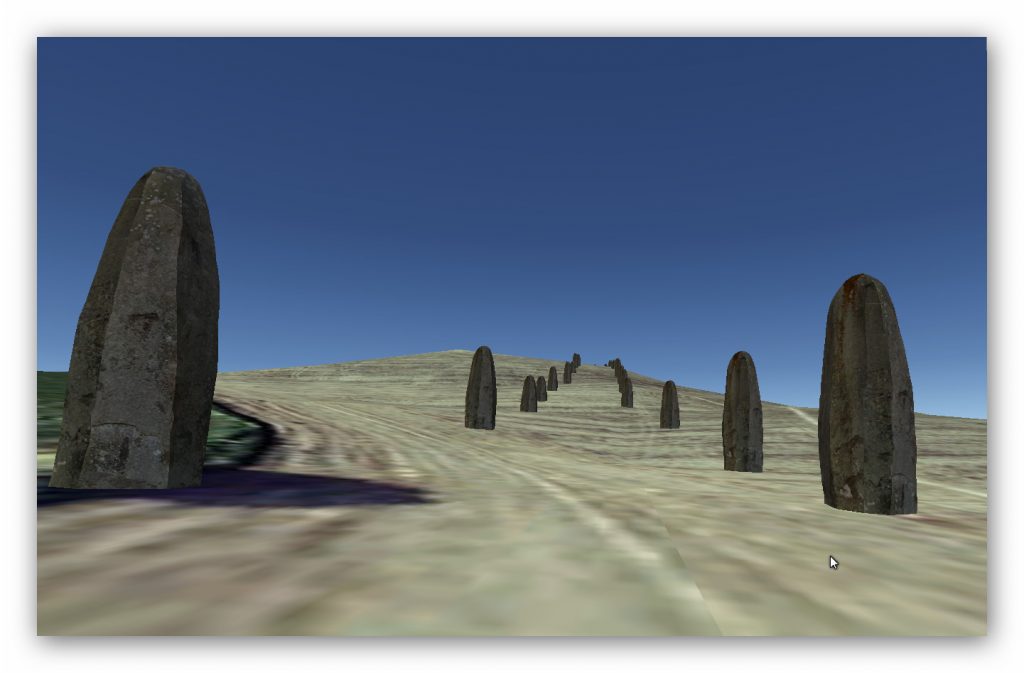

In 2014 a remarkable new Stone Avenue was located at the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Avebury in Wiltshire. Previously, two other Stone Avenues called the ‘West Kennet’, and the ‘Beckhampton’ are known to archaeologists as they have some of the massive Sarsen stones that line these Avenues still present, but this newly discovered pathway was never thought to exist that lead directly to Silbury Hill.

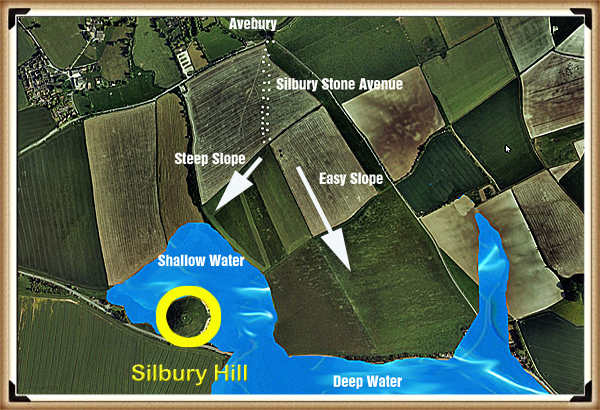

| Figure 73– Waden Hill showing the patch marks of stone holes under the soil – silbury hill lighthouse |

As the discoverer, I have named the pathway ‘Silbury Avenue’ as it is merely the path directly to Silbury Hill over Waden Hill. The discovery was made by digital photographic pictures that show a series of green ‘patches’ that measures over 470 metres in length towards the apex of the hill. We can therefore estimate if it ran down the far side of the hill towards Silbury Hill, it would have been approximately 1470 metres in total length.

From these measurements and by counting the discolourations of this new Avenue, we can estimate that ‘Silbury Avenue’ had at least 19 pairs of stones to the apex with an average of 25m between each pair. We can also estimate the width of this avenue at about 15m to 20m. In comparison, the West Kennet Avenue (calculated from Google Earth) has a pairing at a distance of about 22 – 24 metres, and a width of the Avenue is approximately 15m to 17m – so a very close match.

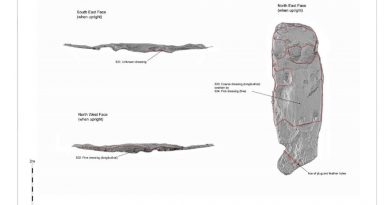

Excavations and restoration work carried out by Keiller and Piggot in 1936 on the West Kennet Avenue showed that this part of the Avenue was built in series of ten straight sections and not the smooth serpentine shape as suggested by the eighteenth-century antiquarian Stukeley.

Where stones were missing, they placed concrete markers above the excavated stone holes where they had formally stood, so providing a record of the northern section of the Avenue. Paradoxically, Keiller’s plan survey of this section of the West Kennet Avenue shows it heading away from the southern entrance of the henge, while ‘other’ pairs seem to repair this ‘error’ with an awkward zig-zag route to connect with the southern entrance.

Recent archaeological commentary on the Avenue has suggested two interpretations for this convoluted approach route. Burl claimed that this was a mistake, of the prehistoric builders in starting the Avenue at both ends but failing to anticipate an accurate direction for each section to join up (Burl 2002). But Gillings & Pollard argued that Keiller’s excavation plan is a mistake, and re-excavation will establish a more direct route for this section of the Avenue (Gillings and Pollard 2004, p. 78).

Yet quite rightly (Sims 2009) suggested that if it were a mistake, then it cannot explain why elsewhere in the Avebury monument there are more complex highly accurate pre-planned features.

The reality is that Burl, Gillings and Pollard are all wrong, as the discovery of my new avenue shows why such a strange ‘zig-zag’ shape was formed – as the original stones were aligned with ‘Silbury Avenue’ from an earlier date than the West Kennet Avenue. This Avenue led directly to Silbury Hill but was then abandoned for a path leading SE around the base of the hill to ‘The Sanctuary’, at a later date.

Moreover, an earlier antiquarian of the seventeenth-century, John Aubrey, recorded how the other end of the Avenue connected to the western entrance of the Sanctuary with the exact same dog-leg design. Showing the two ends of West Kennet Avenue were additions.

The change of direction on the Southern section of West Kennet Avenue shows that this Avenue was used at a very late date in Avebury’s history and after the Sanctuary’s construction. This would explain why the Sanctuary was altered so many times in its past. The likelihood is that The Sanctuary was the termination point of the ‘Ridgeway’ over an adjacent hill.

| Figure 75 – the ‘Zig Zag’ Avenue currently seen is simply explained – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

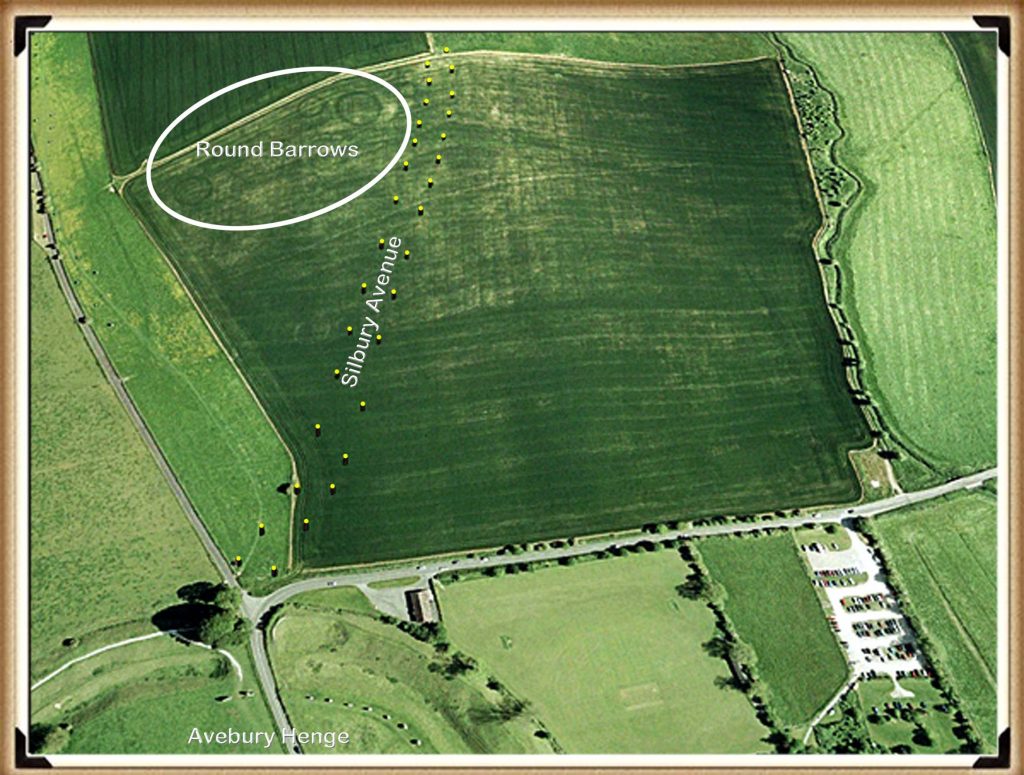

Silbury Avenue doesn’t go in the shortest line to Silbury Hill, but to the highest point, where we find a series of nine Barrows directly to the east side of the new Avenue. Archaeologists have dated these features as Bronze Age, although no excavations have ever been attempted as the barrows (or other features on top of the hill) were destroyed even before Stukeley visited the site in the 18th century.

The only significant findings made in this area was in “An oval-shaped pit”, three feet deep, and discovered by workmen in 1913 while digging a trench for water pipes on Waden Hill. The pit, situated 105m NE of the pond on the hill, contained Windmill Hill sherds, sarsen muller, two flint scrapers, charcoal and burnt flints, together with broken bones of sheep, pig and ox, some of them burnt.”

The barrows on the left of Silbury Avenue indicate that these features were built after the Avenue was constructed and not because of them, as the path passes the barrows to one side without termination. Although the new

| Figure 76– Waden Hill showing the pathway stones and the Round Barrows at the Apex to the left only – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

Avenue would have led towards Silbury Hill, it did not terminate at the monument as it was inaccessible due to it being surrounded by deep water, which can still be seen today during the winter seasons.

The topology shows that Silbury Hill would have been built as part of the River Kennet, on a natural peninsula. This high groundwater table which causes this flooding is due to springs that have recently been located. (Whitehead, P. and M. Edmunds. 2012. Palaeohydrology of the Kennet, Swallowhead Springs and the Sitting of Silbury Hill, English Heritage, Research Report Series 12-2012.

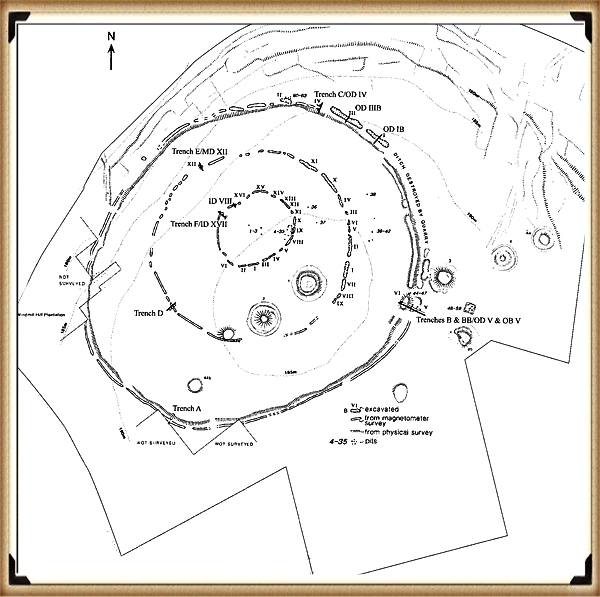

After the ‘great melt’ of the last ice age, this area would have been almost completely flooded at the start of the Mesolithic period. The only part of Avebury above this ‘initial water level’ would have been Windmill Hill – which is NW of the current Avebury site. This site shows evidence of occupation as it is what archaeologists call a ‘Causewayed Enclosure’, as they (incorrectly) imagine, that the moats built to accommodate boats were, in fact, dry ditches in an attempt to contain cattle – although a fence would have been quicker and more effective.

Windmill Hill

The use of this site for this purpose of storing cattle is nonsense, as the time and effort required to dig a ditch rather than build a fence is immeasurable. Although, I have no doubt that after their original use, many thousands of years later, they did serve the purpose of farmers who could not afford nor had the time to build fences.

I have renamed these monuments ‘Concentric Circle’ sites, as they are a product of the same civilisation as the ‘megalithic builders’ and have this very distinctive design feature, of which Greek philosophers and writers have left a written history and used that term to describe their trading sites.

Once the waters of the Mesolithic subsided, a couple of thousand years later, Windmill Hill would have not been accessible by boat and therefore another site closer to the new water’s edge would have been required – this is the Avebury we know today. Consequently, the ditches were built to accommodate (like Windmill Hill) the ships and boats of this trading civilisation.

| Figure 77 – Windmill Hill – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

Unfortunately for our ancestors, the groundwater levels continued to recede, as they have done consistently since the end of the last ice age. When the waters failed to reach the moats of Avebury, and they faced the same option as they had two thousand years earlier to either – to abandon or replace?

Again, they decided to replace, our ancestors, therefore, moved the boats to a natural harbour slightly downriver from Avebury at a place we call Silbury Hill. The River Kennet would have been much smaller in the Neolithic Period, but still three to four times larger than today.

Silbury Hill

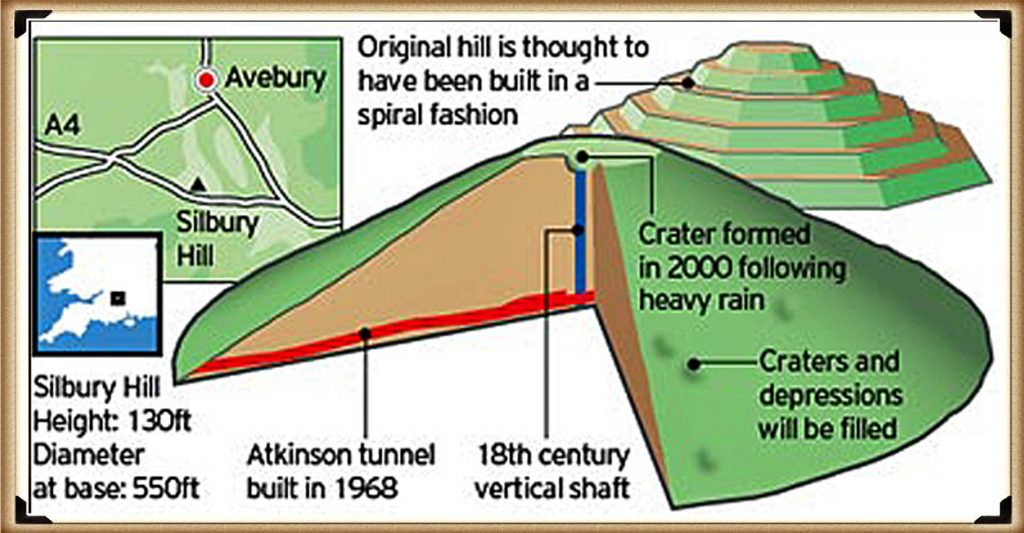

If you understand how the landscape looked and was used in the past, then such beacons can be easily found all over Britain, even ones built, to a similar design to Silbury hill To find this unique design we can look at the most recent re-excavation and detailed examination of Silbury Hill, by English Heritage. For only a few years ago it needed to be ‘shored up’ because of the reckless archaeologists of the past, cutting vast tunnels and shafts into the hill, looking for tombs and treasure making it totally unstable. This investigation showed for the first time that the hill was built like the pyramids of Egypt and South America in steps. This is from The Daily Mail in 2010:

| Figure 78 – Silbury Hill made like a ‘layer cake’ – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

Silbury Hill – one of the most mysterious and striking monuments in Britain – was a prehistoric ‘cathedral’, built layer by layer over 100 years, a new study suggests. The 4,000 year-old earth mound, which towers over the Wiltshire countryside, was the tallest human-made structure in Europe until the Middle Ages.

However, despite its size, and repeated attempts to tunnel into the heart of the mound, archaeologists have long been puzzled about how and why it was created.

Now a new book published by English Heritage suggests that the 120 ft high hill was not built to a grand blueprint but was assembled by at least three generations of Bronze Age Britons between 2400 and 2300 BC. A study of soil, rocks, gravel and tools inside the hill shows that it went through 15 distinct stages of development.

Dr Jim Leary, English Heritage archaeologist, said the creators were building the mound as part of a ‘continuous storytelling ritual’ – and that the final shape of the mound may have been unimportant. He argues that the familiar outline of stepped sides and the flat top visible today is primarily the result of Anglo-Saxons and later alterations.

“Most interpretations of Silbury Hill have, up to now, concentrated on its monumental size and its final shape,’ he said. ‘It has generally been thought to be a concerted effort of generations of people building something out of a common vision and spiritual zeal akin to that spurred the creation of soaring medieval cathedrals.

‘The flat top, especially, was often seen to be a “platform” deliberately built to bring people closer to the skies. ‘But new evidence is increasing telling us that our Neolithic ancestors display an almost obsessive desire to constantly change the monument – to rearrange, tweak and adjust it. It’s as if the final form of the Hill did not matter – it was the construction process that was important.”

Silbury Hill lies close to the stone circles of Avebury and a few miles from Stonehenge. Archaeologists estimate that it would have taken 700 men working for ten years to build out of soil and chalk. It started as a low gravel mound before it was transformed into a pile of soil and rock surrounded by a ditch.

Dr Leary added: “The most intriguing discovery is the repeated occurrence of antler picks, gravel, chalk and stones in different kinds of layering, in ways that suggest that these materials and their different combinations had symbolic meanings. We don’t know what myths they were representing but they must have meant something quite compelling and personal.

What we do know is that by the time work on the hill had started in the later Neolithic period, the surrounding area was already saturated with evidence of past use; it was a place that was heavily inscribed with folk memories that recalled ancestors and their origins. What is emerging is a picture of Neolithic people having the same need to anchor and share ideas and stories as we do now, and that built structures like Silbury Hill may not be conceived as grand monuments of worship but intimate gestures of communication.”

The hill was damaged in the 18th century when archaeologists sank a vertical shaft from the top. In the 1840s, a tunnel was dug into the mound from the edge, while in 1968 BBC2 filmed a new attempt to tunnel into the centre of the mound.

After parts of the mound began to sink in 2002, English Heritage reopened the BBC tunnel, took samples of soil and rock, filled in the gaps and sealed the mound for good.

Dr Leary now believes the mound went through 15 stages of construction – and up to 100 different phases within four or five generations. It would make sense that a monument was a round-based hill made in layers (similar to Marlborough Mound – sometimes known as Merlin’s Barrow, also excavated by Dr Leary, hence his idea!). The question not answered by archaeologists is – why build this monument in stages?

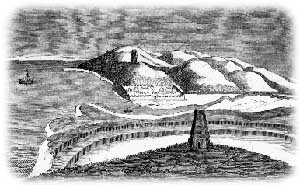

Fortunately, the answer is simple – to make it higher, for Silbury was a beacon to attract ships to its harbour. Over time the height of the mound was raised to increase the beacon’s visibility.

| Figure 79 – Marlborough Mount – Built like Silbury Hill – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

‘The flat top, especially, was often seen to be a “platform” deliberately built to bring people closer to the skies.

Unfortunately, the article is also full of nonsense like this quotation. So, the ancestors built a hill at the bottom of a valley to get closer to the skies – is it me, or can anyone see the error in this statement? You may therefore respond to my criticism by asking – wouldn’t a beacon on top of a hill have greater visibility? Yet the reason the beacon is located in the watery harbour and not on top of a hill is that the light shows the exact location of mooring places, in bad weather and at night, when visibility is poor.

This type of device can be seen throughout our recent nautical history as illustrated at the Spurn Point Lighthouse. The earliest reference to a lighthouse on Spurn Point is 1427, which was a coal-fired lighthouse at the ground level. There were several lighthouses of various designs until in 1767; John Smeaton was commissioned to build a new pair of lighthouses (one a 90ft tower). The 1895 lighthouse is a round brick tower, 128ft tall, painted black and white. It was designed by Thomas Matthews. Its main light had a range of 17 nautical miles.

Silbury Hill also started at ground level and was built up (like Spurn Point) over hundreds of years until it reached the 120ft height seen today.

From the Guardian 31st May 2011

For generations, it has been scrambled up with pride by students at Marlborough College. But the mysterious, pudding-shaped mound in the grounds of the Wiltshire public school now looks set to gain far wider acclaim as scientists have revealed it is a prehistoric monument of international importance.

After thorough excavations, the Marlborough mound is now thought to be around 4,400 years old, making it roughly contemporary with the nearby, and far more renowned, Silbury Hill.

The new evidence was described by one archaeologist, an expert on ancient ritual sites in the area, as “an astonishing discovery”. Both Neolithic structures are likely to have been constructed over many generations.

The Marlborough mound had been thought to date back to Norman times. It was believed to be the base of a castle built 50 years after the Norman invasion and later landscaped as a 17th-century garden feature. But it has now been dated to around 2400BC from four samples of charcoal taken from the core of the 19-metre-high hill.

The Marlborough mound has been called “Silbury’s little sister”, after the more famous artificial hill on the outskirts of Avebury, which is the largest manmade prehistoric hill in Europe.

Marlborough, at two-thirds the height of Silbury, now becomes the second largest prehistoric mound in Britain; it may yet be confirmed as the second largest in Europe.

Jim Leary, the English Heritage archaeologist who led a recent excavation of Silbury, said: “This is an astonishing discovery. The Marlborough mound has been one of the biggest mysteries in the Wessex landscape. For centuries, people have wondered whether it is Silbury’s little sister, and now we have an answer. This is a very exciting time for British prehistory.”

Fire Beacon

Marlborough Mound shows that fires were light on the hill throughout its use, and the same fact can be found at Silbury Hill. Jim Leary’s excavations showed signs of fire and associated dates for these charcoal remains. According to jim:

Old Land Surface

Sample: OxA-20808

Hazelnut fragments (from the same hazelnut) from [4041] – sample <9821>, sub sample of <9435>. [4041] is a concentration of charcoal comprising charred hazel nutshell fragments and other charred remains as well as two pig or wild boar teeth. It was recorded within a small, defined area of the upper part of the OLS (4041]) on the north side of the East Lateral in Bay 7, and is thought to indicate the remains of a hearth.

Radiocarbon Date: 4012±29; 2620–2460 cal BC; 2510–2465 cal BC

Sample: SUERC- 24089

Maloideae branchwood (single entity) as OxA-20808

Radiocarbon Date: 4030±35; 2840–2470 cal BC; 2510–2465 cal BC

This presence of charcoal is reinforced by: Canti, Matthew & Campbell, Gill & Robinson, D.. (2004). Site Formation, Preservation and Remedial Measures at Silbury Hill. Who reported that: ” The remaining part of Core 5 consisted of around 29 m of chalk rubble from the rest of the mound, and this was also assessed for the presence of biological remains. Samples were taken at 25 cm intervals respecting interfaces, and floated using a 0.25 mm mesh for the flot and a 0.5 mm mesh for the residue. Tiny fragments of charcoal were present at intervals throughout the depth of the mound.”

This clearly shows that both Fire beacons were used around 2400 – 2500 BCE, when the Neolithic Waters were still high and could carry boats.

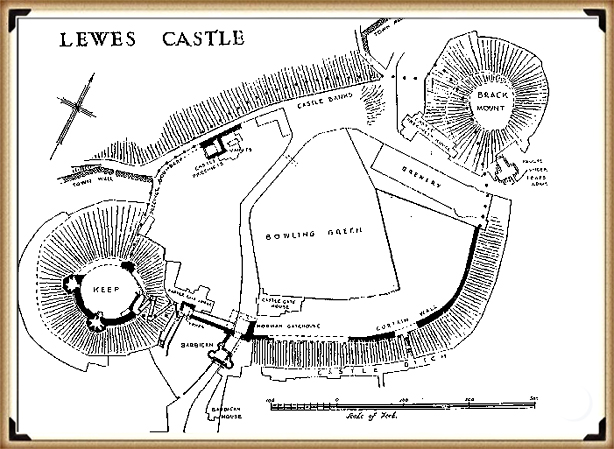

| Figure 80 – Lewes Castle with a ‘second mount’ – which predates the Norman fortifications – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

We find these beacons throughout Britain, but they remain undiscovered by archaeologists as they are believed to be Norman in origin. Sadly, this is the simplistic nature of archaeology – if it’s a mound – it must be a Norman Motte and Bailey – if it has a ditch and on top of a hill – it must be an Iron Age fort?

In Lewes, on the South Downs, there are two beacons in this small Sussex village, both had the same function – to attract shipping. The first is prehistoric and called the ‘Brack Mount’, historians here believe it was part of the old Norman Castle and show pictures of a wall connecting the traditional Motte and Bailey with this ‘additional feature’.

Recent excavations have shown that this beacon has a Norman well installed at the top of the mount (probably for the castle?), the problem for archaeologists and historians dating the mound is – why on earth would you build a 50 foot high earth mound, and then dig a 60ft well, unless it predates the Norman Castle?

| Figure 81– Lewes Tump – used by the ‘Cluny’ monks to attract ships from the English Channel – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

Lewes in Prehistoric times was one of the largest inland harbours in Britain, and this mound would have had a fire on top to attract shipping. If that was not interesting enough and an excellent example of a beacon for ships and boats, a second one was built some four thousand years later, when the groundwaters of Lewes (like Avebury) were much lower. This was built for the Monks of the French Cluny Monastery that obtained supplies and people from France and needed to show their location along the English Channel just after the Norman conquest when maps were – not very accurate!

The Harbour

Silbury Hill was built as a beacon for Avebury within a deep natural port, that now surrounds the Hill which still floods in wet winters. However, they had a problem as the trading centre Avebury was just under a kilometre from this new port and therefore, a trackway was needed to be constructed to the old site.

Silbury Stone Avenue was this new pathway. It goes from Silbury Hill harbour to Avebury over Waden Hill; this trackway was lined with the same gigantic sarsen stones we now see currently in West Kennet Stone Avenue and also believed to have existed in Beckhampton Avenue.

Photographic evidence shows that the Silbury Stone Avenue went to the apex of Waden Hill beside the ploughed-out barrows located to the eastern side of this new Avenue. The most direct route from the peak would have been an SSW direction towards the base of Silbury Hill, but the gradient down this slope is large and would be an improbable route for ladened carts.

| Figure 82– Silbury Avenue – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

The best route for travellers would have been a longer, but with a far easier gradient to walk and carry goods, so not surprisingly, this path (which is still in existence today) and also used as a boundary marker between fields, can be found down the centre of the hill.

We have found at sites like Old Sarum and the Avenue at Stonehenge, loading platforms placed on the ends of tracks and edges of the ditches, where boats used to dock and load. So, therefore, did Silbury Avenue have something similar?

The answer was found on a ‘LiDAR’ map of the area which showed a large mound at the end of the suspected avenue.

In 2004, Pete Glastonbury (photographer) rediscovered what he termed ’Silbaby’ mound. This mound appears in early archaeological maps of Avebury but was lost through the introduction of the A4 on Ordinance Survey maps. After six years of campaigning and requesting an investigation, soil samples were finally taken to date the mound (which had always been presumed to be a modern dumping ground from the A4’s construction).

So, the archaeologists thanked Pete for all his hard work, diligence and years of campaigning, but as he was not an ‘archaeological professional’, or a member of the elite ‘academia club’, they renamed his Silbaby – ‘Waden Mount’ – now that’s what I call archaeological politics for you.

Midway between Silbury Hill and the road that runs from West Kennet to the henge is what appears to be the remains of a mound that has a resemblance to the profile of Silbury. It lies just to the south of the main A4 road that runs alongside Silbury itself and, though partly obscured by vegetation, is quite visible to visitors going to the West Kennet Long Barrow. It is relatively large when compared to most of the round-barrows in the area and must contain a substantial amount of material.

For want of something more formal, its similarity in shape to Silbury Hill has generated the nickname of “Silbaby” although the text of William Stukeley’s book mentions “Weedon Hill” which might be a reference to it.

Curiously, though being a prominent feature in such an important landscape, very little appears to be known about it despite much research by local photographer Pete Glastonbury who has now brought it to the attention of archaeologists in the hope that it will soon receive some serious investigation. If it does prove to be contemporary with Avebury’s other ancient monuments its unusual position on the flood-plain of the river ( as opposed to the usual hill-top position of Bronze Age

| Figure 83– Waden Mount – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

round barrows ) and closeness to the enclosures will make it a fascinating site for theorists.

William Stukeley appears to have recorded a feature at the same position and some old illustrations and maps also show it though others seem to ignore it. Of significance must be the fact that it is connected to the river by a small and probably artificially enhanced spur that carries the water of Waden Spring on which the mound appears to sit. The proximity of the road makes it difficult to judge quite what the original profile of the mound may have been if it does precede the Roman period. With the recent discovery of a substantial Roman settlement in the area, there is the possibility that it may be a legacy of our continental visitors.

The evidence of some more recent earthmoving may ultimately be found to be responsible, or its artificial appearance might just be the chance result of natural forces at work, but until an explanation for its existence is found it will surely remain another enigma amongst the many others that already exist at Avebury. Perhaps the central mystery about it currently is why, when this landscape has been crawled over by numerous archaeologists and researchers during the past century or more, has it apparently been ignored?

Core samples were taken in 2010, and we await the official findings – but preliminary reports from Pete suggest it is human-made and has a similar composition and therefore date to Silbury Hill.

| Figure 84– Waden Hill showing the two possible pathways from the apex of the hill |

Waden Mound (Silbaby) was built at the end of Silbury Stone Avenue for a reason. We know that it was surrounded by water as the Waden Spring is found even today at its base, and the external view of the mound is round like Silbury Hill. From its height and size protruding into what would have been the raised water levels of the Kennet, it was more likely made specifically for the Silbury Stone Avenue, as a stable earth platform to load boats as seen at other sites like Old Sarum and Stonehenge

The research into Silbury Hill’s use is still ongoing and even today as I write this paragraph; I have new LiDAR scans of this area, which indicate that the path over the centre of Waden Hill may have been 20m West of the current track. The scan shows a deep indent which may be the original footpath which leads from the apex even more directly to Waden Mount. Only real excavation work will answer this question in time, and that is unlikely as archaeology is grossly underfunded at present, even for such a significant discovery.

The waters around Silbury Hill eventually dried up as the groundwater receded even further over the next thousand or so years – therefore, a new mooring point was needed to maintain Avebury’s trading status. At this time, there doesn’t seem to be another typical harbour on the River Kennet available, so they created the final loading point on the River allowing traders to unload their ships and probably smaller boats, and this new loading quay is called ‘The Sanctuary’ which was once the natural termination point of the Ridgeway path (supposedly Britain’s oldest pathway) which led to the ‘Uffington White Horse’.

It’s entirely possible that the use of the Sanctuary was a sign of Avebury’s concluding days as a trading centre. As the mooring point was on the River, this would limit the number of boats that could moor daily. It is quite feasible that Silbury Hill beacon could still have been used as a lighthouse, as shipping would need to pass the Sanctuary before reaching Silbury Hill.

Moreover, it’s also possible that technology was by this time more advanced, and as we saw from the example of ‘Spurn point lighthouse’ a new type of lighthouse structure was developed. If we look for a description of The Sanctuary, we find it’s both peculiar and familiar at the same time.

Situated beside the A4 road on Overton Hill the Sanctuary is the site of a stone circle that once formed the terminal point of the West Kennet Avenue. Large enough to contain the outer ring of stones at Stonehenge, its earliest parts are dated to around 3000 BC, which is about the same period the cove in the northern inner circle of the henge was erected. Unless any evidence to the contrary is found it is believed to have only become linked to the distant henge when the avenue was built about 2400 BC.

| Figure 85– Silbury Hill was a lighthouse/Fire beacon for the Harbour below – Silbury Hill Lighthouse |

Now destroyed and only consisting of small concrete markers where the various elements once stood, the Sanctuary must have played an important part in the function of the henge. When Aubrey saw it he recorded it as a double ring of stones. Although Stukeley also recorded quite a number of stones on his drawing of it he was to witness much of its destruction during the period of his visits. The destruction was so complete that the site was to become lost and forgotten until Mrs. Maud Cunnington was able to locate it once more in 1930 prior to her excavation of it.

It is a confusing site from an archaeological point of view. Despite a number of excavations (one as recent as 1999), it continues to be a challenge to researchers. It appears to have started as a series of small circles comprising of wooden posts, some of which have now been established as being quite massive. Whether these were evidence of a roofed building or just remained as standing posts is the subject of debate. Eventually, after many modifications, it was to evolve into a stone circle about 130 feet in diameter which has now disappeared. Whatever its purpose it remains an essential and fascinating part of the Avebury complex.

Consequently, when Silbury harbour dried up, this was the only logical landing site on the River Kennet near Avebury. So, they built a wooden lighthouse-like Woodhenge with the same external diameter of 138ft but with a smaller inner timber circle and posts just up to 24 inches wide (not 60 as at Woodhenge) and hence probably half the size high.

Moreover, Silbury Avenue was now redundant, and so they moved the large avenue sarsen stones from on top of the hill down to the east side and created West Kennet Avenue as we see today – with the ‘zig-zag’ kink and path correction as you enter Avebury.

Still find it hard to believe this function is common place for nautical societies?

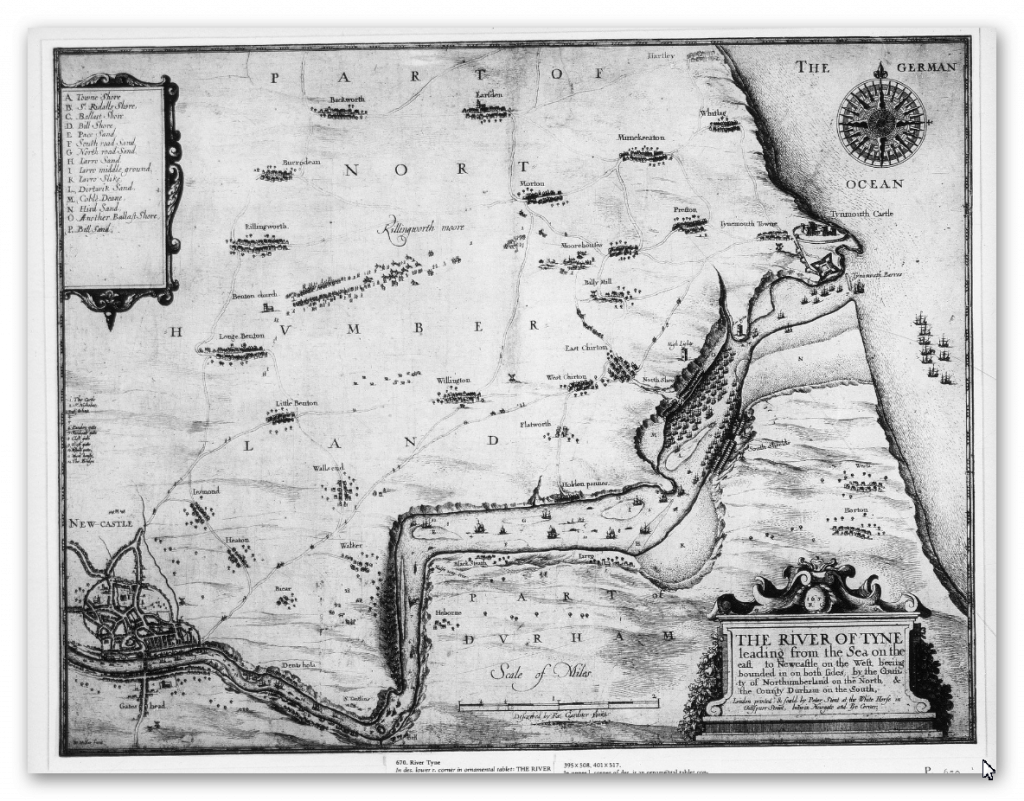

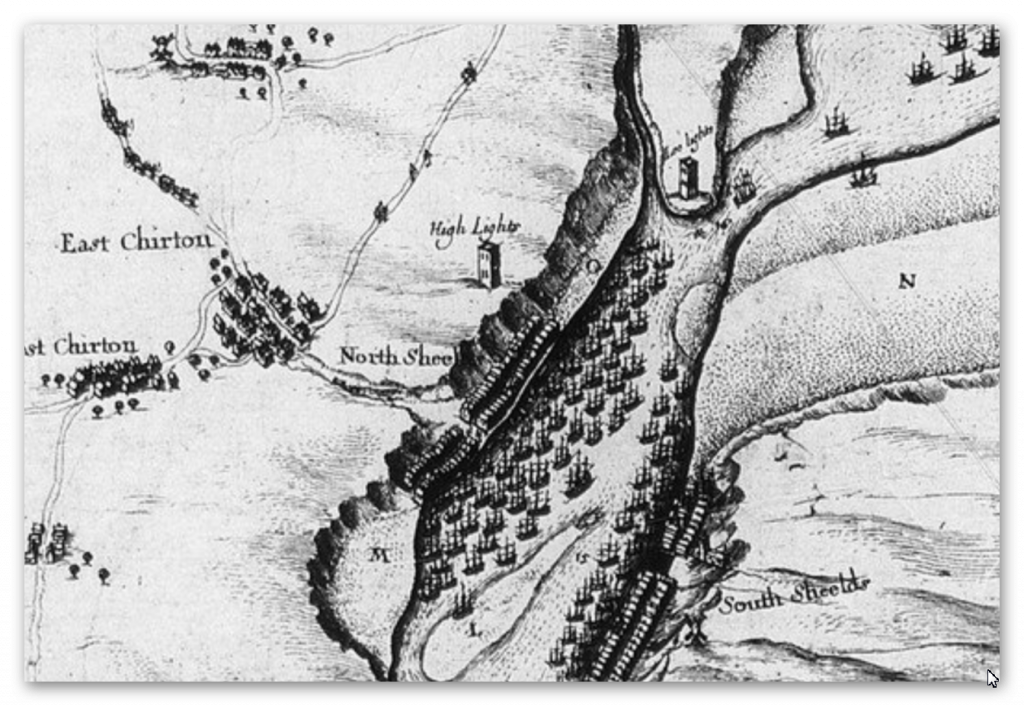

The historical role of lighthouses has always fascinated me, and it’s clear that their purpose extended well beyond simply warning ships of danger. When we delve into the past, we discover that lighthouses were beacons, guiding vessels to safe harbours, even within rivers. The 17th-century map of the River Tyne is a vivid example of this concept.

In that era, lighthouses played a pivotal role in maritime navigation. They not only ensured safe passage during adverse weather conditions but also signified the presence of harbours where ships could find refuge, conduct maintenance, and make necessary repairs. These beacons were lifelines for sailors and the cornerstones of maritime trade and commerce.

The map of the River Tyne with its two lighthouses tells a compelling story of historical navigation. It reveals a network of guiding lights that not only aided ships but also fostered the growth and prosperity of the communities they served. It’s a testament to the enduring legacy of lighthouses as symbols of safety, hope, and refuge in the world of seafaring.

We should also not forget that the oldest Lighthouse in Britain is Roman and were also built in pairs (Like Silbury and the Sanctuary) at Dover again to ATTRACT ships to port.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

To understand why rivers were larger in the past we have video with all the relevant information.