Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

The Indian campaign of Alexander the Great began in 326 BCE. Alexander was born July 20, 356 BCE in Pella, in the Kingdom of Macedonia. During his leadership, he united the Greek city-states and led the Corinthian League. He also became the king of Persia, Babylon and Asia, and created Macedonian colonies in Iran. After conquering the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, the Macedonian king (and now high king of the Persian Empire) Alexander launched a campaign in northwest India (what is now Pakistan.) Many historians consider the Battle of the Hydaspes river against King Porus in Punjab as the most costly Battle that the armies of Alexander fought.

The rationale for this campaign is usually said to be Alexander’s desire to conquer the entire known world, which the Greeks thought ended in north-western India. However, while considering the conquests of Carthage and Rome, Alexander died in Babylon on June 13, 323 BCE. In 321 BCE, two years after Alexander’s death, Chandragupta Maurya of Magadha, founded the Maurya Empire in India.

Purushottama (Poros) a Kshatriya on the Hydaspes River (Jhelum River) in the Punjab of Pakistan, near Bhera. The Hydaspes was the last major battle fought by Alexander. The main train went into modern-day Pakistan through the Khyber Pass, but a smaller force under the personal command of Alexander went through the northern route, resulting in the Siege of Aornos along the way. In early spring of the following year, he combined his forces and allied with Taxiles (also Ambhi), the King of Taxila, against his neighbour, the King of Hydaspes.

Porus wiz Puru was a great King of Indus/ Asiatic continent. Arrian writes about Porus, in his own words, “One of the Indian Kings called Porus a man remarkable alike for his strength and noble courage, on hearing the report about Alexander, began to prepare for the inevitable. Accordingly, when hostilities broke out, he ordered his army to attack Macedonians from whom he demanded their king as if he was his private enemy. Alexander lost no time in joining battle, but his horse being wounded in the first charge; he fell headlong to the ground and was saved by his attendants who hastened up to his assistance.”

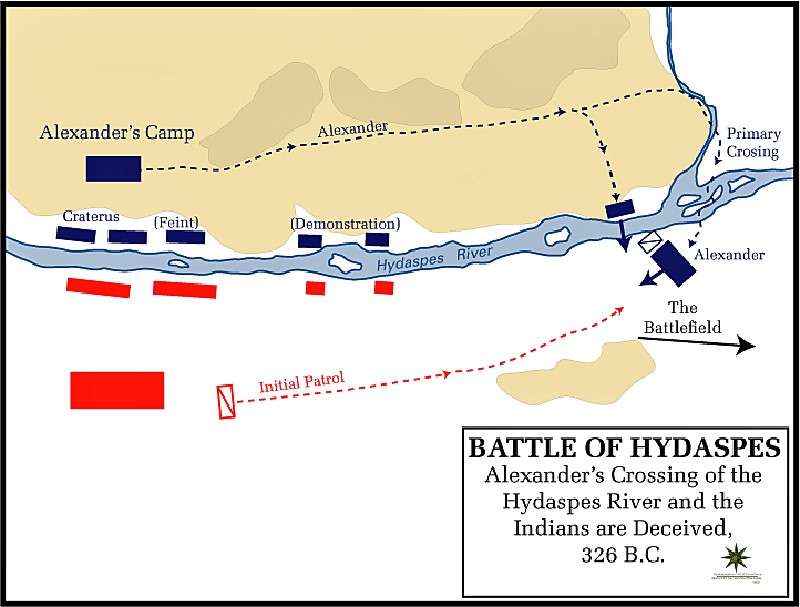

Porus drew upon the south bank of the Jhelum River and was set to repel any crossings. The Jhelum River was deep and fast enough that any opposed crossing would probably doom the entire attacking force. Alexander knew that a direct crossing would fail, so he found a suitable crossing, about 27 km (17 miles) upstream of his camp. The name of the place is ‘Kadee’. Alexander left his general Craterus behind with most of the army while he crossed the river upstream with a substantial part of his army. Porus sent a small cavalry and chariot force under his son to the crossing.

According to sources, Alexander first encountered Porus’s son in the past, so the two men were not strangers. However, Porus’s son killed Alexander’s horse with one blow, and Alexander fell to the ground. Arrian, also writing about the same encounter, adds that “Other writers state that there was a fight at the actual landing between Alexander’s cavalry and a force of Indians commanded by Porus’s son, who was there ready to oppose them with superior numbers, and that in the course of fighting he (Porus’s son) wounded Alexander with his hand and struck the blow which killed his (Alexander’s) beloved horse Buccaphalus.”

The force was easily routed, and there isn’t any mention in any account that Porus’ son was killed. Porus now saw that the crossing point was more extensive and decided to face it with the bulk of his army. Porus’s armies were poised with cavalry on both flanks, the war elephants in front, and infantry behind the elephants. These war elephants presented a complicated situation for Alexander, as they scared the Macedonian horses.

Alexander did not continue, thus leaving all the headwaters of the Indus River unconquered. Afterwards, Alexander founded Alexandria Nikaia (Victory), located at the battle site, to commemorate his triumph. He also founded Alexandria Bucephalus on the opposite bank of the river in memory of his much-cherished horse, Bucephalus, who carried Alexander through the Indian subcontinent, and died heroically during the Battle of Hydaspes.

Near the Ganges River (the Hellenic version of the Indian name Ganga), East of Porus’s kingdom was the mighty Nanda Empire of Magadha and Gangaridai Empire of Bengal. Fearing the prospects of facing other powerful Indian armies and exhausted by years of campaigning, his army mutinied at the Hyphasis River (the modern Beas River), refusing to march further East.

As for the Macedonians, however, their struggle with Porus blunted their courage and stayed their further advance into India. For having had all they could do to repulse an enemy who mustered only twenty thousand infantry and two thousand horse; they violently opposed Alexander when he insisted on crossing the river Ganges also, the width of which, as they learned, was thirty-two furlongs, its depth a hundred fathoms, while its banks on the further side were covered with multitudes of men-at-arms and horsemen and elephants. For they were told that the kings of the Ganderites and Praesii were awaiting them with eighty thousand horsemen, two hundred thousand footmen, eight thousand chariots, and six thousand fighting elephants.

Gangaridai – a nation which possessed a vast force of the largest-sized elephants. Owing to this, their country has never been conquered by any foreign king: for all other nation’s dread, the overwhelming number and strength of these animals. Thus, Alexander the Macedonian, after defeating all Asia, did not make war upon the Gangaridai, as he did on all others; for when he had arrived with all his troops at the river Ganges, he abandoned as hopeless an invasion of the Gangaridai when he learned that they possessed four thousand elephants well-trained and equipped for war.

This is a traditional account of how Alexander entered and fought in India. To access this land, he had to travel thousands of miles east to a new land. Traditionally, this campaign was seen as a route march over barren desert land, which, to be frank, nobody in their right mind would attempt. However, recently a Photojournalist (not a historian) physically travelled the same path as Alexander the great and found that he used the waterways of the past, which to date have been ignored as they are currently too low to facilitate such a large army, but in the past, David suggests that the river was much larger than today.

In search of the Alexander’s Lost World (TV Documentary), David Adams followed in the footsteps of the earliest Greek explorers, putting a new theory on Jason and the Argonauts to the test.

Aboard a replica of the Argo, David Adams embarked on an epic journey from Greece across half the earth and into war-torn Afghanistan. In Russia, David discovered the Phasis River, the waterway that led Jason to ‘The land of the Golden Fleece’ and onto the Caspian Sea, where Alexander planned to create a great canal to connect it to the Black Sea.

He entered Alexander’s Lost World in search of the mysterious River Oxus that, according to the Ancient Greeks, once flowed into the Caspian, transporting riches from India. In the desert wastes of Turkmenistan, he also discovered the ruins of a magnificent 4,000-year-old city and startling evidence to suggest that the reports of the Ancient Greeks were correct; in their time, the earth’s climate was radically different than today.

Crossing into Afghanistan in search of the lost city of Bactra, Adams uses the Ancient Greek accounts as a guide to try to locate Alexander’s fabled Central Asian Capital. Long thought to be the citadel of Balkh, the Greeks accounts appear to describe a different city entirely. In the markets beneath the fortress, David found evidence to suggest Bactra may lie out towards the Oxus River at the end of a great delta.

Continuing his historical journey, David travelled along Alexander’s route of conquest through Uzbekistan and Tajikistan to unearth Alexandria on the Oxus. Moreover, in the waters of the Oxus River, Adams discovers a surprising connection to Jason and the Argonauts – could they have possibly travelled this far from Greece?

The story of the golden fleece is remarkably similar to a process still practised today on the banks of the Oxus in Uzbekistan where river water is poured down a slope on top of a piece of sheep’s fleece, which catches the gold in its wool-like a filter.

David found extraordinary evidence that this lost world was once connected to the west. On the Pakistan border, David meets with the fabled ‘Children of Alexander’ and determines – once and for all – Alexander’s relationship with them. When the road turns to river and rubble, he finds the remains of other invaders and their unexplored citadel – Chinese and Tibetans, who, just like Alexander, once fought for control of the trade routes in an epic battle of 20,000 men.

Moreover, on his final leg of his Quest for Alexander’s lost world, he found evidence of the earliest communities, including farming and irrigation above 4000 meters – evidence that long ago, a radically different climate made farming possible on the roof of the world. The most remarkable aspect of this civilisation is that they were doing this long before Alexandra the Great, some estimate 7,000 years ago.

Finally, he journeys on, deep into the high Pamir Mountains on Afghanistan’s border with China; he goes in search of the trustworthy source of the Oxus River – it remains undetermined until this day, and he measured the flow and volumes, before making the final push to the place he believes is the source – an ice cave at the base of a glacier. Which is the last ice age would have been far more significant in size and the source of greater volumes of water, making the Oxus river far deeper and accessible?

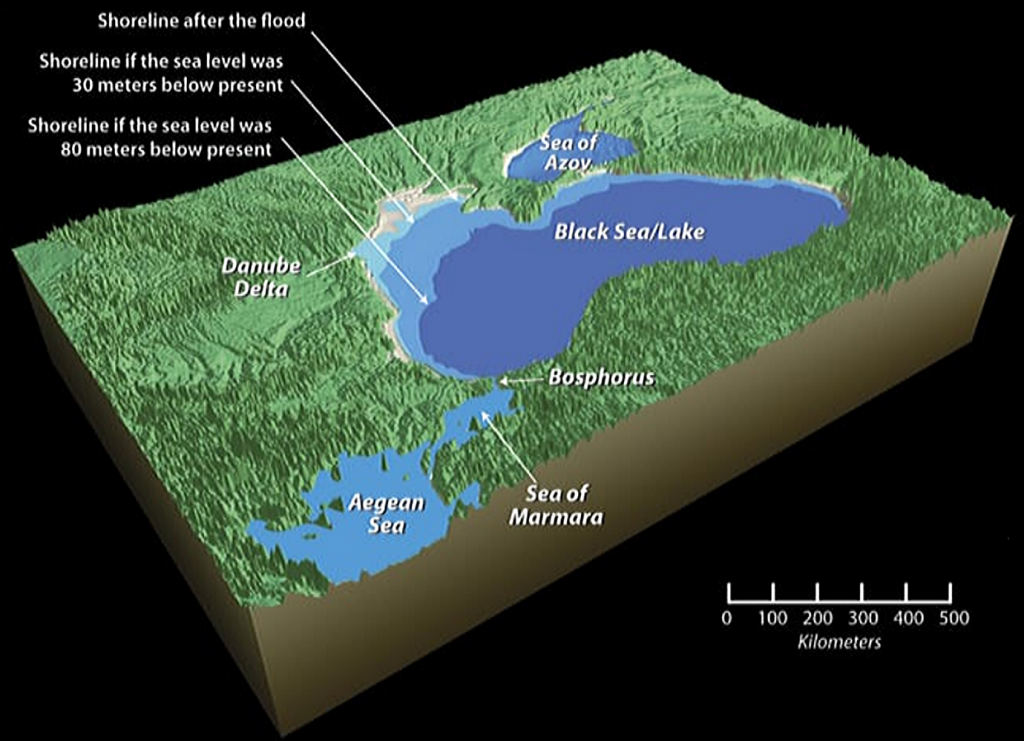

So it seems that the last Ice Age influenced even the Greek and Roman periods some 15,000 years later. The story of Jason and the Argonauts is clearly based on the Greeks sailing up the Oxus in search of adventure. Alexander the great could not have accessed India without the Flooding of the Black and Caspian Seas compared to today that allowed him to connect with the Oxus in the Caspian and sail to Lake Aral before starting his journey South West to Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan and finally Pakistan (India) some 2,000 miles without ships and boats, for travel and supplies.

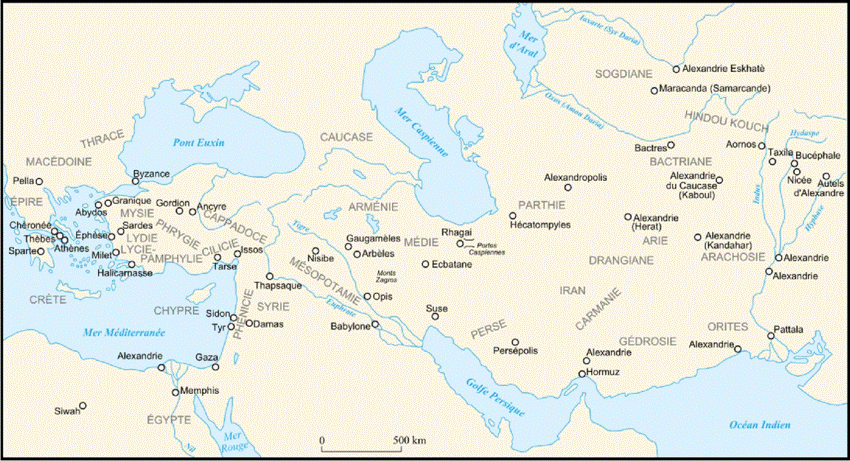

This route is confirmed by the naming of conquered towns with his course, which still bear the name Alexandria such as Eschate:

Alexandria Eschate (Latin: Alexandria Ultima, English meaning “Alexandria the Farthest”) or Alexandria Eskhata was founded by Alexander the Great in August 329 BCE as his most northerly base in Central Asia. It was established in the southwestern part of the Fergana Valley, on the southern bank of the river Jaxartes (modern name Syr Darya).

On the banks of the Jaxartes River – there is the Ai-Khanum:

Ai-Khanoum or Ay Khanum (lit. “Lady Moon” in Uzbek, possibly the historical Alexandria on the Oxus, also possibly later named Eucratidia) was one of the primary cities of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. Previous scholars have argued that Ai Khanoum was founded in the late 4th century BCE, following the conquests of Alexander the Great. However, the most recent analysis strongly suggests that the city was founded after 280 BCE by the Seleucid King Antiochus I. The city is located in Takhar Province, northern Afghanistan, at the confluence of the Oxus River (today’s Amu Darya) and the Kokcha river, and at the doorstep of the Indian subcontinent.

On the banks of the Oxus and Kokcha Rivers – is Alexandria in Aria:

Aria was an Old Persian satrapy, which enclosed chiefly the valley of the Hari River (this being eponymous to the whole land according to Arrian) and which in antiquity was considered as particularly fertile and, above all, rich in wine. Mountain ranges separated the region of Aria from the Paropamisadae in the east.

On the banks of the Hari River – there’s Alexandria in Margiana.

Merv, formerly Achaemenid Satrapy of Margiana, and later Alexandria and Antiochia in Margiana, was a major oasis-city in Central Asia, on the historical Silk Road, located near today’s Mary in Turkmenistan? Several cities have existed on this site, which is significant for the interchange of culture and politics at a location of significant strategic value. It is claimed that Merv was briefly the largest city in the world in the 12th century. The oasis of Merv is situated on the Murghab River that flows down from Afghanistan, on the southern edge of the Karakum Desert,

On the banks of the Murghab River – last but not least Kapisa:

Alexandria on the Caucasus (medieval Kapisa, modern Bagram) was Alexander the Great (one of many colonies designated with the name Alexandria). He founded the colony at an essential junction of communications in the southern foothills of the Hindu Kush mountains, in the country of the Paropamisade. Alexander populated the city with 7,000 Macedonians, 3,000 mercenaries and thousands of natives (according to Curtius VII.3.23), or some 7,000 natives and 3,000 non-military camp followers and a number of Greek mercenaries (Diodorus, XVII.83.2), in March 329 BCE. He also built forts in what is nowadays Bagram in Afghanistan, at the foot of the Hindu Kush, replacing forts erected in much the same place by Persia’s King Cyrus the Great c. 500 BCE. Still, the waters of the Kabul, Panjshir, and Khorband rivers created a fertile alluvial plain, and the city was to become very prosperous.

On the banks of the Panjshir and Khorband Rivers (Which no doubt was used to transport and feed these towns and outposts of Alexandra’s empire?)

Is his most famous city Alexandria— which become the world centre of the learned from Europe, Asia, and Africa. Its position was unrivalled. Situated at the mouth of the Nile, it commanded the Mediterranean Sea, while by means of the Red Sea, it held easy communication with India and Arabia. When Egypt had come under the sway of Alexander, he had made one of his generals’ rule over that country, and men of intellect collected there to study and to write. A library was started, and a Greek, Eratosthenes, held a librarian at Alexandria for forty years, namely, from 240 -190 B.C. During this period, he made a collection of all the travels and books of earth description—the first the world had ever known—and stored them in the Great Library of which he must have felt so justly proud and a legacy to the world. (Alexander the Great)

Ironically, the famous librarian drew a map of the world for his library at Alexandria, but it has perished with all the rest of the valuable treasure collected in this once celebrated city by a nation we consider to be the modern civilisation model Romans. We know that he must have made a great many mistakes in drawing a map of his little island world, which measured eight thousand miles by three thousand eight hundred miles. However, the Caspian Sea was connected with a Northern Ocean, and the Danube sent a tributary to the Adriatic – is this another indication that post-global flooding was still being felt long after the ice had disappeared? (Alexander the Great)

One thing is for sure. Without the raised waters of the Caspian and Black Seas and the glacier that feed the Oxus in Afghanistan, Alexander would have had an Empire much smaller than we celebrate today.

For more information on Global flooding check out this website or this video channel.

Further Reading (Alexander the Great)

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’. (Alexander the Great)

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group

(Alexander the Great)

Pingback: Alexander the Great's Arrival in the Indian Subcontinent: From Origins to the Eastern Campaign | Infipark.com