Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

“Antler Picks” – From Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology

“A type of tool found widely among the sites of Neolithic communities in North-Western Europe. They are formed from a red-deer antler from which all but the brow tine has been removed; the beam forms the handle, and the brow tine the ‘pick’. They were used for excavating soil and quarrying out stone and bedrock. The marks left by their use have been detected on the sides of ditches, pits, and shafts. Experiments suggest that they were used rather more like levers than the kind of pickaxe that is swung from over the shoulder.”

If you read any book or watch a program about archaeology and the construction of their monuments and sites, you will hear the experts talk about the findings of antler picks in the general vicinity and link the building with these objects. As the description above indicates, these ‘tools’ are from red deer, which shed these natural growths annually.

According to archaeologists, this was the primary tool of prehistoric people – a natural resource that became a handy tool in excavating the ditches and digging holes in the chalk bedrock that surrounded most of their sites. This is where the Victorian term ‘antler picks’ originates and still exists today, but for an unknown reason, this tool has now changed its use (but not its name), as archaeologists have now realised that if these ‘antlers’ were used to cut into hard bedrock chalk, they would leave blunt ends and scars from flint re-sharpening, which there is no evidence. So ‘Antler picks’ have now turned into ‘Antler levers’ although the wording has remained the same – confused?

That’s archaeology for you!

Yet, if you look at any prehistoric report about the monument’s construction, you find a degree of ‘acceptance’ that antlers were used as the primary source of digging out the chalk downlands. For example, here is a typical report from English Heritage’s ‘bible’ (Stonehenge in its landscape, 1995, cleal et al.) and the use of Antler picks.

“Over 130 antler implements are known to survive from excavations by Gowland, Hawley and Atkinson et al. Antler implements have frequently been associated with Neolithic and Early Bronze Age monuments in Britain located on chalk or limestone, and it is generally assumed that they were the principal implements used in the digging of ditches, postholes and stone holes.”

In a paper on Neolithic engineering, Atkinson (1961) wrote, ‘the tools used – antler picks, bone wedges and occasionally stone axes – are well-known and require no further discussion’ However, some of the generalisations made in the literature about antler implements require modification in the light of the finds from Stonehenge.”

The first thing you notice is the complete arrogance of Atkinson with the comment ‘are well-known and require no further discussion’ for this was the archaeological opinion in the ’60s, 70s and even ’80s. This was when monuments such as Stonehenge were ‘scientifi cally dated’ and were accepted beyond any doubt, but as the line added after by English Heritage (EH), this was far from the truth. ‘require modification’ is a politically correct way of suggesting that Atkinson was utterly wrong.

The report continues, “The 118 antlers and antler fragments in Salisbury Museum constitute about 87% of the known extant collection. Measurements were taken following Clutton-Brock(1984). Some were taken on those parts of the antler which were unmodified, and from these, it is possible to estimate the size of the animals from which the antler was obtained. Additional measurements of cultural significance were taken, including the length of the pick and the angle between the used ‘tine’ and the beam.”

The ‘tine’ is the ‘horn’ that comes off the central antler column after the ‘head connector’ called the ‘base’ or shed; it is thicker and the hardest of all the antler horns. On an antler, there are usually three ‘tines’ – the Brow (first after the base), the Bez (second after the base) and the Trez. After the three ‘Tines’ comes the larger crowns, which are longer but much thinner.

Here comes EH’s first admission that the myth that is still dominant today even amongst the knowledgeable archaeological community today “Popular works have tended to oversimplify the antler tools and perpetuate some interpretations, which do not stand up to scrutiny. Examinations of the assemblage from Stonehenge have shown that the methods of modification and the forms of the picks are more varied than has hitherto been appreciated.

So what on earth are they going on about?

The Victorian Archaeologists found antlers all over Stonehenge and in the ditches that had filled up over the years, so the conclusion as it was ‘perceived’ that metal had not been found at the time of these monuments construction is that these instruments must have been used to dig the ditches and holes of these monuments – but there are practical problems to this idea if you look closer!

The only part of the antler that could break the solid chalk successfully is the harder ‘tines’. The problem with the tines is that they all grow the same way, so they would not allow a clean strike at the chalk bedrock if used as a ‘pick’ unless you removed two of the three tines. And hence the ‘gobbledygook’ sorry line in the EH report that says ‘methods of modification, and the forms of the picks are more varied than has hitherto been appreciated.

If we see systematic use and preparation of these tools as has been suggested by archaeologists in the past, we should see two clean cuts with a stone axe or cutter to ‘prune’ the antler and the third that is used to smash the chalk broken by the constant compression – but we don’t!

Of the 118 antler picks found at Stonehenge, 82 antlers had the harder tines attached. Of the 82 with tines, only 25 had the other two smaller tines removed; only 21% of the antler finds. However, remember this was the entire finds for Stonehenge, which archaeologists have suggested was constructed in Three Phases over 700 years.

Phase I – was the ditch, bank and Aubrey holes, which would have contained the Bluestones from Wales. It has been estimated that a total of 87,000 cubic feet of chalk taking (at least) 30,000 working hours was removed in this phase. According to the location of the discarded antlers, there were only seven antlers that had their bases, and the strongest tine attached, producing the most efficient tool possible. This would mean that each whole antler had removed 12,429 cu feet, without damage.

An impossible task?

Sadly, even more, impossible than this massive figure suggests is that we have not considered the size of the antler. The bigger, the better for, the longer the antler, the better the levering motion to remove chalk blocks. This being the case, they must have used the most giant antlers possible, especially when you consider that the number of Deer in Britain in prehistoric times is far greater than today and ‘bucks’ shed their antlers on an annual basis. At present, there are 1.5m Red Deer in Britain – even with the exact size of the population in prehistoric times, the builders of Stonehenge would have at least half a million antlers per annum to collect and use.

Consequently, only the largest antlers should have been available ‘to an organised society to select?

I state this fact, as we know that this same civilisation could muster a group of people to not only dig out 87,000 cubic ft of chalk but also obtain 56 Bluestones 200 miles away from the Preseli Mountains in Wales – so the collection of antlers which over the years must have shed millions must have been a simple matter.

However, the evidence shows that this was far from the truth. The distribution analysis shows that of the total number of antlers found, their size varies greatly. For example, the average circumference of a typical antler found at Stonehenge is just 210mm (8.5″) this is a diameter of 66mm (2.7″) – some antlers are as small as 150mm in circumference or diameter of 48mm (less than two inches) compared to the largest of 299mm in circumference or 48mm (nearly 4 inches), and that was a single one.

But was this a comfortable size to hold?

Possibly so, depending on the size of the person. However, what is not disputable is the leverage of the tool; the longer the hand axe, the greater the gauging and leverage on removing the chalk blocks?

The statistics we have from English Heritage ‘could be much better’ as they measure only the distance between the bur (the thickest part attached to the head) and the trez, which is the third tine up from the base. The Trez is not the strongest tine on the antler – that is the brow. However, there are so few antlers cut to this correct and more effective way that EH decided this unorthodox method to compare sizes – even so, we can see how these antlers were not selected for their size. The Average size (distance from Bur to Trez) was 190mm (7.5″), so as small as 110mm (4″) – compared to the largest again available of 410mm (16″).

So with millions of antlers on the floor, why would you use anything smaller than the average thickness or length and would you not be inclined to go for the largest possible?

This strange lack of evidence can also be seen in other monuments where even greater numbers of ‘antler picks’ would be required but have not been found, such as Avebury, which has one of the largest for a monument in Britain it contains three stone circles within. Current archaeological estimates suggest that it took 1.5 million working hours to build the Avebury monument, which includes 3.4 million cubic feet of chalk, forty times larger than Stonehenge – so we should find forty times more Antler picks (3200), in theory.

From Wikipedia

“Excavation at Avebury has been limited. In 1894, Sir Henry Meux put a trench through the bank, which gave the first indication that the earthwork was built in two phases. The site was surveyed and excavated intermittently between 1908 and 1922 by a team of workmen under the direction of Harold St George Gray. He could demonstrate that the Avebury builders had dug down 11 metres (36 ft) into the natural chalk using ‘red deer antlers’ as their primary digging tool, producing a henge ditch with a 9-metre (30 ft) high bank around its perimeter. Gray recorded the base of the ditch as being four metres (13 ft) wide and flat, but later archaeologists have questioned his use of untrained labour to excavate the ditch and suggested that its form may have been different. Gray found few artefacts in the ditchfill, but he did recover scattered human bones, among which jawbones were particularly well represented. At a depth of about two metres (7 ft), Gray found the complete skeleton of a 1.5-metre (5 ft) tall woman.”

Although Grey cut through the ditch and suggests that the building of this structure, the expected vast amounts of discounted antler picks from their labour are minimal to nonexistent. He found more human bones than deer antlers.

So should we, therefore, surmise that they dug the ditch out with their bare hands or parts of human skeletons as only parts of human bones were found – if we follow archaeology logic?

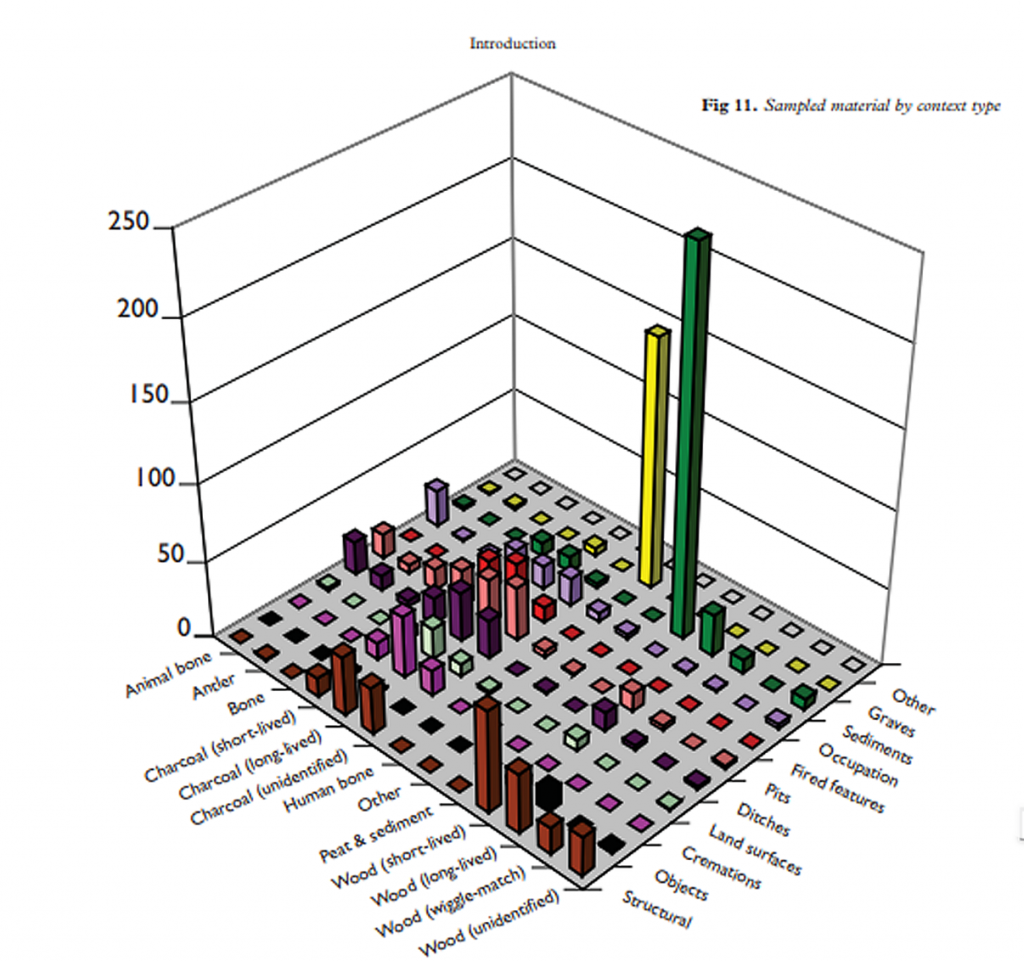

To highlight the absurdity of this antler myth, we need not look any further than English Heritage’s publication called ‘Radiocarbon Dates from samples funded by English heritage from 1981 – 1988’ – one would imagine that if we scratch below the surface of these monuments, the broken reminisces of the tools used to build these magnificent constructions would be obvious. Instead, however, the book tells another story.

Of all the samples found, ‘Antler’ was the second smallest behind Animal Bone, Human Bone, Wood and Charcoal and by a large margin, such as Animal Bone was three times larger than antler (so did they take the antlers and not eat the animal?) However, human bones were five times the most significant find – the reality is they found only three pieces of antler (one from the bank of Avebury in 1937, one from West Kennet Avenue and one from the Avebury ditch in 1909), and even then, we are not sure what parts of the antler were found. So we found just one fragment of antler bone from Avebury’s most significant artificial ditches in Britain.

The facts do not bear out the myth!

So how can a scientific discipline claim that these features were made from antler picks and shoulder blade shovels when there is just one fragment of antler ever carbon-dated at Avebury? The truth is that the myth has grown around the original excavations at Stonehenge, and archaeologists found antler picks in the ditch – in the 20th century; they may have felt that this was unusual as antlers are not found in significant quantities today, but in the past vast herds would have probably fed there before the road systems were invented and dropping antlers would have been commonplace. So to find antlers in an abandoned ditch filled with topsoil and other items left on the topsoil is not uncommon.

So does this affect the date of Stonehenge’s construction?

Sadly, yes, it does. The mistake of accepting (without looking for collaboratory evidence from other sides like Avebury in finding the necessary quantities to justify the link to the ‘tools’ with their construction) antlers as the main artefacts of construction is fundamentally flawed. Consequently, the dates from these artefacts, which Stonehenge is 90% based upon, is therefore totally inaccurate.

Recent findings on carbonised wood (fires) on the Stonehenge site are thousands of years older than the 2 500 BCE date produced from the antler pick dates. This should be no surprise to any archaeologist as the Post Holes in the Stonehenge Visitors Car Park and findings of a mile away at Vespasian Camp are all the exact dates. Yet, archaeologists refuse to accept that the myth is stopping us identifying the true date and nature of our most prised site for fear of ridicule as most of the ‘popular’ archaeologists we see on our TV have published books endorsing both this absurd technique and dates currently supported by English Heritage. The latter is their financial sponsor and overlord.

However, some have broken ranks in recent years and offered tantalising clues on the true nature of our history and the deception game being played by EH. Mike Parker-person in his recent book ‘Stonehenge’, revealed that they found ‘cut marks’ in the chalk in an excavation at Durrington Walls (Woodhenge) that looked like it was made from a ‘metal’ instrument.

Do we see the first evidence that ‘antler picks’ did not make our ancient monuments, but metal axes?

This would make a lot more sense than current archaeological theories – but what is the big deal if this was true? So why not just accept the truth and go forward with these more practical metal devices?

Well, this digs the science into yet another hole (what complex webs we weave when we practise to deceive!) for metal (such as Bronze) was supposedly not invented until about 2,500 BCE – hence the term the Bronze Age (2 500 BCE – 70 BCE). Although a Bronze Age ‘commercial sized’ kiln has been found on the River to the Black Sea, which originated in the North Sea which dates back to 4,500 BCE that used ‘Cornish Tin’ to make the Bronze? Moreover, as we have seen, these deep ditch constructions are much older than the ‘antler picks’ originally dated them.

So is the age of metal much older than we currently believe?

For my own belief, I would have to put back the use of metal to at least 5 000 BCE, which would mean that Britain had Bronze long before the Mediterranean, which would go against all that is currently believe about cultural immigration from East to West, as we have now found much evidence of trading from Britain to Asia Minor in the Mesolithic period – including the boatyards that would have been necessary for such journeys.

For more information go to our website or our YouTube video channel

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group