Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

Contents

Promotional Video – Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – The Vallum

Chapter 1 – Dykes, Ditches and Earthworks……. Book Extract (Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – The Vallum)

The modern word dike or Dyke most likely derives from the Dutch word “dijk”, with the construction of dikes in the Netherlands well attested as early as the 12th century. The 126 kilometres (78 mi) long Westfriese Omringdijk was completed by 1250 and was formed by connecting existing older dikes. The Roman chronicler Tacitus even mentions that the rebellious Batavi pierced dikes to flood their land and protect their retreat (AD 70). The word dijk initially indicated both the trench and the bank.– Wikipedia

If you study archaeology at university or even on an ordinance survey map at length, you will notice strange earthworks on the sides of hills of Britain, with no rational explanation as to why they are there and for what reason. These features are mostly ignored at university, or an excuse is made for their construction. The reality is that these features do not make any sense unless there are other factors in operation which have been ignored.

The first thing to notice is that the word ‘Dyke’ is associated with water. It does seem strange you would call an earthwork on top of a hill a Dyke, unless there was some history passed down through the years to its actual use. If we look at the most famous Dyke in Britain, ‘Offa’, we notice that it is attributed to a Saxon King and, therefore, could not be prehistoric. Or is this a clear indication of how archaeologists find excuses for these features rather than factual, empirical evidence?

“Offa’s Dyke (Welsh: Clawdd Offa) is a massive linear earthwork, roughly followed by some of the current borders between England and Wales. In places, it is up to 65 feet (19.8 m) wide (including its flanking ditch) and 8 feet (2.4 m) in height. In the 8th century, it formed some kind of delineation between the Anglian kingdom of Mercia and the Welsh kingdom of Powys.” – Wikipedia

At face value, this explanation seems to answer all the questions about Dykes (except the water connection). But suppose you delve further down to look at the evidence, such as findings from the Dyke and any written history. In that case, you get a different version for the Roman historian Eutropius in his book, Historiae Romanae Breviarium, written around 369 AD, mentions the Wall of Severus, a structure built by Septimius Severus who was Roman Emperor between 193 AD and 211 AD:

“He had his most recent war in Britain, and to fortify the conquered provinces with all security; he built a wall for 133 miles from sea to sea. He died at York, a reasonably old man, in the sixteenth year and third month of his reign.” – Eutropius (369 AD)

This ‘wall’ need not be made of stone as we know from their Scottish endeavours that the first structure as a defence was usually a bank and a ditch – just like a Dyke!!

The problem with this account is that none of the known Roman defences are 133 miles long – Harridan’s Wall is only 70 miles, so are they talking about Offa’s Dyke, which is much longer?

Chapter 2 – The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis.………… Book Extract (Ancient prehistoric canals – The vallum)

Before we show you what these ‘Linear Earthworks‘ were used for in prehistoric times. We need to give you an idea of how the environment was at the time of construction and why it is so different today.

In ‘The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis,’ we looked at the new mathematical models that allowed us to calculate the amount of water released during and after the Last Glacial Maximum just over ten thousand years ago.

If the Dykes of Britain are canals (and not markers or defensive ditches), we must prove that the water table was higher in the past than today (otherwise, they would still be flooded).

The models contained in the PGFH showed us that a minimum of 8.42 quadrillion tonnes of water was released on the UK at the end of the last ice age. This is equivalent to 98425.2 inches of rain falling on every square inch of Britain’s landmass or the same as – One Inch of rain steadily falling every day for the next 270 years

The worst known flooding in British history occurred in 1947 when just six inches of rain (149mm) fell on up to 12″ of snow (so a maximum of 15″ of rain if melted) over three months. The flooding, which inundated nearly all the main rivers in the South, Midlands, and the Northeast of England, was notable for its origins, geographical extent, and duration.

It impacted thirty out of the forty English counties over two weeks, when around 700,000 acres of land flooded. As a result, tens of thousands of people were temporarily displaced from their homes, and thousands of acres of crops were lost; and this was just 15 of the estimated equivalent of 98,425 inches of water that was shed on the British landscape after the last Ice Age.

Raised Water Table

According to William Donn (Donn et al., 1962). The Fennoscandian and Great Britain ice sheet covered 4.7 106 km2, which is equivalent to:

• 8.42 106 Gigatonnes of water / 4.7 106 km2, which gives us 1.79 Gt per km2

• 1.79 Gt of water at a penetration rate of 43%, give us 0.77 Gt of water per km2

• 0.77 Gigatonnes of water by UK landmass 242,495 km² give us 186,804 Gt of groundwater

This water will be released at a rate of 1 – 12mm per annum and possibly at a depth of 75km. Therefore, to release groundwater at a depth of 75km at an average rate of 6mm per annum would take 12,500 years – not the 1,200 years previously believed, which is just the surface water from the last stages of the meltwater ice.

This is why rivers (like the Thames) still flow even after months of drought, as the groundwater is constantly leaking into the river, which was at its highest rate at the start of the Mesolithic, just after the great meltwater floods.

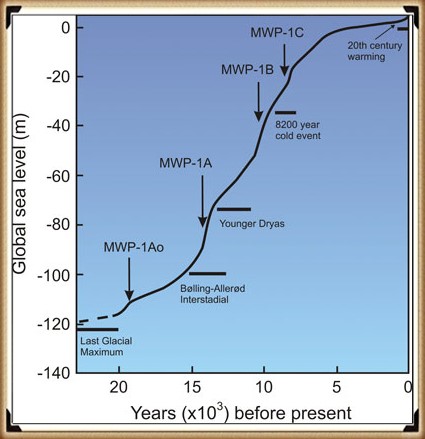

Sea-Level Changes

If this model is correct, we should be able to get verification via other empirical evidence, as shown in sea level water rises, to see if it has been constant over the last 12,500 years.

Most geologists and paleoclimatologists, when talking about the end of the last ice age, refer people to the phenomenon called the ‘Meltwater Pulse’ – which is the rapid rise in sea level (20m) between 13,500 and 14,700 years before present, over a 400 – 500 year period. Although it is a tremendous value, it should be recognised that this ‘pulse’ as only 16% of the total sea rise since the end of the last ice age.

Chapter 3 – Hydrology 101………….. Book Extract (Ancient prehistoric canals – The vallum)

When it comes to the use of ‘linear earthworks’ (we call ‘Dykes’), there is massive confusion amongst both professionals and amateur archaeologists about how such structures could function when they are dry today?

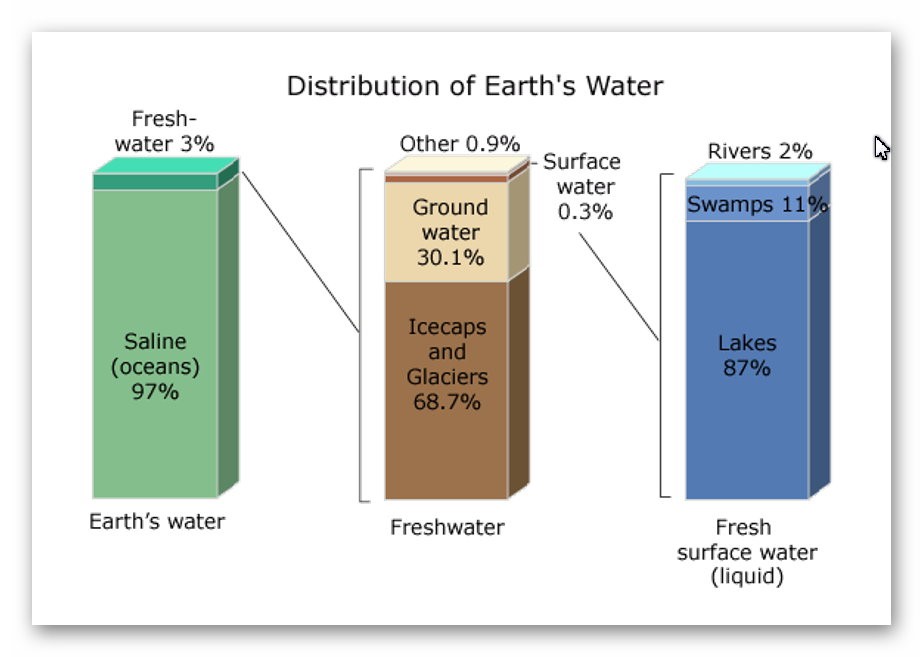

The incorrect perception of these ‘Dykes’ is either they are ‘rivers’ (like the Thames) that flow uphill or Victorian Canals with locks and wooden gates regulating the flow of the water – which are equally nonsensical as a prehistoric structures. Basic Hydrology that most people (should be but not necessarily ALL) learnt at school is that water is under the ground – not just a little water but 30% of all the fresh water on the planet.

This abundance of ‘groundwater’ is evident as it is the source of ALL rivers and supplies the Wells that have been dug since the beginning of time when rivers were absent. Even today, if you go into your garden and dig a hole, it will eventually fill with groundwater, whether in a valley or on top of a hill or mountain.

How and why water is on hills is very challenging for individuals as most people have a simplistic view of water being flat and sitting at ground level – but the earth is a far more complicated structure as this is the reason that it took centuries for people to recognise that we lived on a sphere and not a ‘flat-earth’ as such complex concepts such as gravity are hard to comprehend.

The reality is that ‘streams’ of water are encapsulated within the bedrock allowing ‘springs’ to start rivers at a great height as the groundwater is under pressure and erupts to the surface from BELOW and does not flow up or down the hill internally – but can flow downhill AFTER it escapes from the soil, because at the point of escape gravity then becomes the greater force overcoming the water pressure when within the bedrock – which stops it flowing down the landscape and can push it up to the top of hills and mountains.

Consequently, wells work even on hills as the groundwater is encapsulated in the bedrock and soil. The above illustration shows that if wells are dug halfway up a hill where there is a groundwater pocket, they will fill – if we join up these wells, the entire ditch will also fill with water – sourced from the ground.

The central aspect that must be remembered when considering the reasons behind the construction and maintenance of these earthworks (Dykes) is that the environment was so much different in the Mesolithic Period, which changed rapidly when entering the Neolithic and then even more changes in the Bronze and Iron Ages.

Once the ice sheets had melted and the climate began to warm, the landscape gradually changed from open tundra to dense woodland. By around 8000 BC, pine and birch dominated the woodland cover. These were slowly replaced by lime, elm and oak with some hazel. By 6500 BC, pine and birch woodland would only have been found on the thinner limestone soils of the uplands.

Case Study Wansdyke – Morgan’s Hill West………. Book Extract

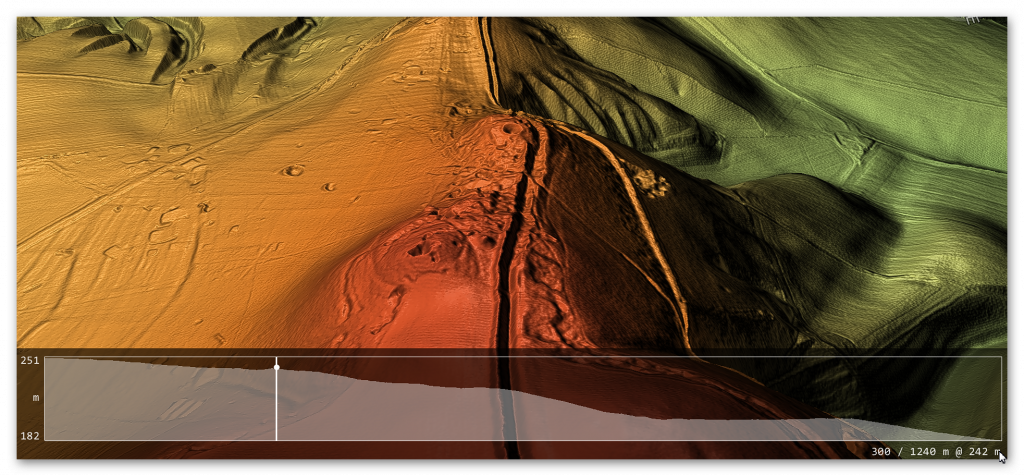

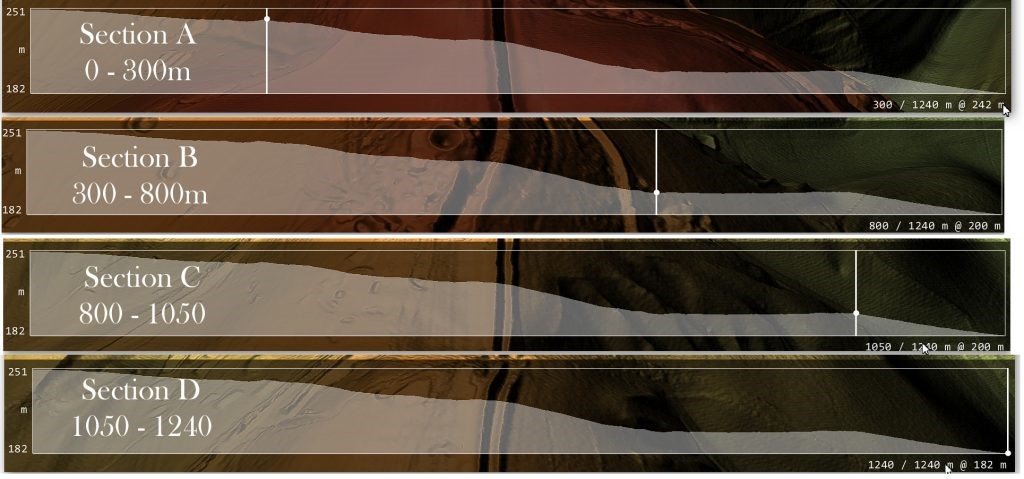

The steepest aspect of Wansdyke is the rise over Morgan’s Hill, which is an incline from 182m OD to 252m OD.

If we are correct with our assumption, we need to show that you can transverse this massive incline using natural springs and basic wooden weirs. If we split the gradient into four parts, we can see better the profile and problems our ancestors faced.

Section A – 0 to 300 downhill

Length is 300m, and the inclination lowers from 251m OD to 242m OD at a ratio of 3% or 1:33 – If we accept that within this section, we had four cat A ‘springs’ that would release 11.2 cu. metres of water PER SECOND (11,200 litres per second) would fill a 10m ditch that is 1.5 deep by one-metre width of the Dyke’s ditch every SECOND.

According to the mathematical formula (v = k * C * R0.63 * S0.54 ), water at the end of section A would be travelling at 5 MPH – the speed of the Thames at Henley (so quite navigable) and, therefore, no need for any Weirs to reduce the water flow.

Section B – 300 to 800m downhill

This section would receive water at one metre per second from Section A, travelling at 5 MPH – The length of this section is 500m in length, and the inclination lowers from 242m OD to 200m at a ratio of 8% or 1:12 this would accelerate the water to 15 mph which is too fast the navigate uphill. Therefore, a series of weirs would have been placed either under the water or, as the early Victorians achieved, by a paddle weir or both.

An underwater weir (blocking 50% of the water but allowing boats to move over the top without hindrance) would reduce the flow by 50% – so if placed at the End of Section A (at 5 MPH) would reduce the water flow to 2.5 MPH and down to 12.5 MPH at the End of Section B. Consequently, if we place one of these 50% reduction weirs at 100m intervals the water flow would not go over the 5-mph mark and would probably be in the region of 3 – 5 MPH which again is easily navigable.

Section C – 500 to 1050m downhill

The length of this Section is 550m at an inclination of 0% – its flat the only water flow movement will be from the residue movement from Section B – another 50% weir could kill this if they wanted 550m of dead water to allow the animals or people dragging the boats to rest before the next incline?

Section D – 1050 to 1240m downhill

The length of this section is 190m at an inclination of 200 to 182m at a ratio of 9.5% or 1:9.5 – the length of this section in the Mesolithic would be questionable as the river Kennet during this time may have covered this section, and so not a problem. But at a later date, if this section was required (i.e. during the Roman period), then like section B a 50% weir every 100m would slow the water flow below five mph.

Sections A – V

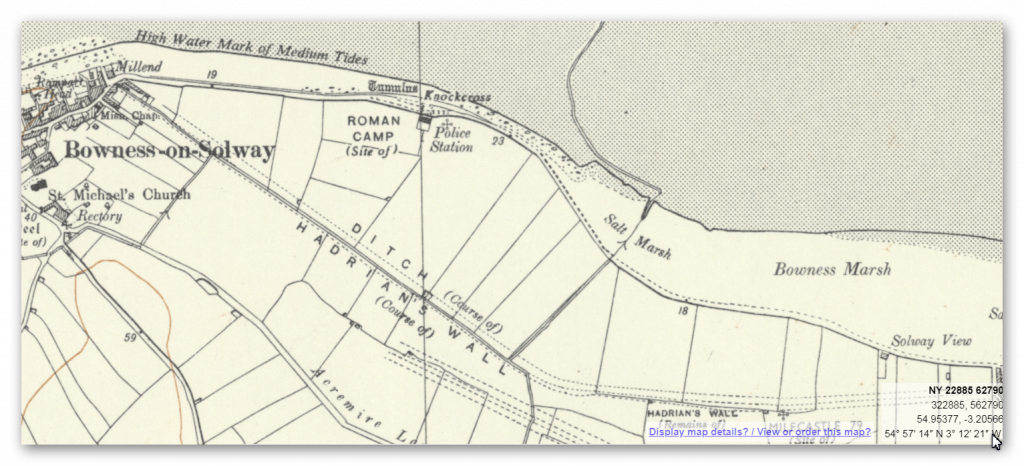

Section A – NY26SW

| Existing Vallum Length (m) | Missing Vallum (m) | Gaps / River Valleys (Depth) | Springs (within 200m) | Quarries (within 200m) | Ancient Sites (within 200m) |

| 2742 | 492 (15%) | 3 (1m) | 1 | 0 | 2 |

Historic England Sections: Hadrian’s Wall between Westfield to Bowness-on-Solway in wall miles 76, 77, 78 and 79

List UID: 1015951, 1016021, 1014701, 1014700, 1014699, 1015904, 101503

Old OS Map

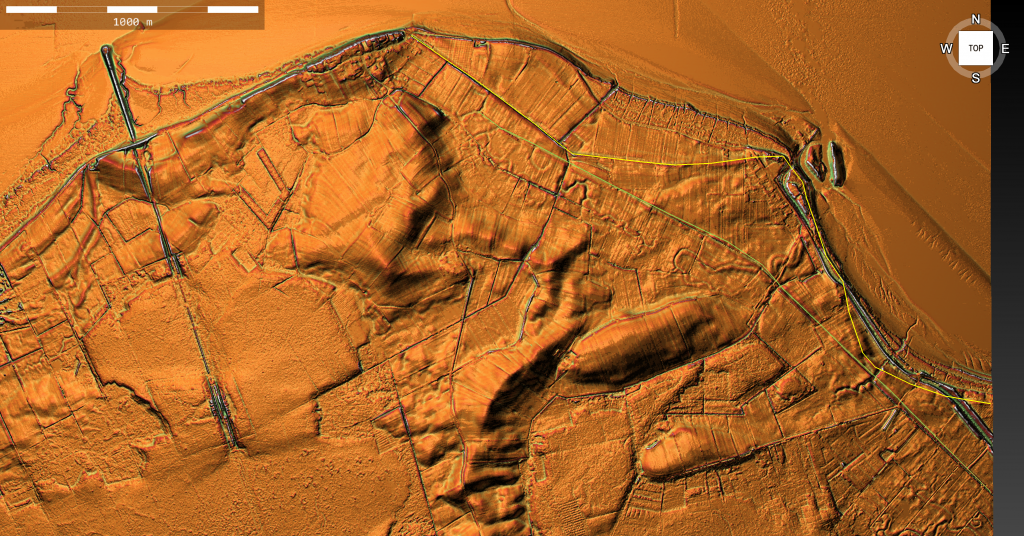

LiDAR Map

Google Earth Map

Historic England Scheduled Monuments – Section A

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between Port Carlisle and Bowness-on-Solway in wall miles 78 and 79

List UID: 1015951

Name: Hadrian’s Wall vallum between the track south of Kirkland House and Bowness-on-Solway in wall miles 78 and 79

List UID: 1016021

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between the access road to Glendale caravan park and the track south of Kirkland House in wall miles 77 and 78

List UID: 1014701

Name: Hadrian’s Wall vallum between the watercourse 400m south east of Glasson and the access road to Glendale caravan park in wall miles 76 and 77

List UID: 1014700

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between the dismantled railway and the access road to Glendale caravan park in wall mile 77

List UID: 1015904

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between Apple Garth, Westfield, and the dismantled railway in wall mile 77

List UID: 1015903

Name: Drumburgh Roman fort and Hadrian’s Wall between Burgh Marsh and Westfield House in wall miles 76 and 77

List UID: 1014699

English Heritage scheduled reports of this monument suggests that:

Hadrian’s Wall runs westwards along the crest of a raised beach from Port Carlisle for 700m and then turns north west to run towards Bowness-on-Solway.

West of the site of milecastle 79, for a distance of 200m, the remains of the Wall lie beneath a field boundary visible as a bank 1m high surmounted by a hedge…..

The Wall in this sector was initially constructed in turf, which was replaced on the same line in the second half of the second century AD by the Stone Wall. It has not yet been determined whether the Wall was fronted by a ditch in this section. The proximity of the coast would have made a ditch superfluous and a ditch of the normal wall ditch proportions would have been liable to tidal flooding.

The difference in thickness of the south and west walls and the evidence that it was originally built as a free-standing tower abutted by the Turf Wall demonstrated it to be the type of turret characteristic of the Turf Wall, and the most westerly turret known on Hadrian’s Wall. When the Wall was rebuilt in stone, the Turf Wall turrets, which were originally built in stone themselves, were retained with the new wall.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has not been confirmed in this section. It is expected to run parallel to the Wall a few metres from its south face.

The course of the Vallum is known in this section with intermittent surface traces visible. The Vallum ditch survives as a faint shallow depression and a short section of the south mound is visible as an earthwork averaging 0.5m high to the south west of milecastle 79. Elsewhere the Vallum mounds are not visible on the ground and survive as buried remains.

The course of the Vallum westwards is not known from a point 150m west of the measured site of turret 79a, and its western terminus has not yet been discovered. The Vallum is therefore not included within the scheduling west of this point.

The monument consists of the section of Hadrian’s Wall and the Vallum between the access road to Glendale caravan park in the east and the track south of Kirkland House in the west.

Hadrian’s Wall survives throughout this section as a buried feature. West of milecastle 78 the Wall turns northwards to follow the Solway coast in contrast to the Vallum which runs straight in this section. It is not certain whether the ditch to the north of the Wall was provided in this section, as a ditch would have been superfluous so close to the shore and liable to tidal flooding. There is no evidence for the ditch on its depicted line. The Wall in this sector was initially constructed in turf, which was replaced in the second half of the second century by the stone wall.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has not been confirmed in this section.

The course of the Vallum is known in this section. The Vallum ditch can be traced as a depression up to 0.8m deep. The Vallum mounds are not visible in this section and have been reduced and levelled by ploughing. They survive as buried features.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall vallum between the watercourse 400m south east of Glasson in the east and the east side of the access road to Glendale caravan park in the west.

The Vallum survives as a feature visible on the ground throughout most of this section. At the eastern end of the monument the Vallum ditch is utilised by a modern drainage ditch 5.7m wide and 2m deep.

The course of the Vallum between the watercourse 400m south east of Glasson and Burgh Marsh has not yet been confirmed and is therefore not included in the scheduling. West of Glasson the line of the Vallum ditch is visible as a faint shallow depression but at the west end of the monument it survives in the field immediately east of the access track to Glendale caravan park as a more obvious earthwork up to 0.8m in depth.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall between the dismantled railway 200m west of Westfield House in the east and the access road to Glendale caravan park in the west.

Hadrian’s Wall survives throughout this section as a buried feature. It is not known whether the ditch to the north of the Wall was provided here as the wall runs parallel to and close to the Solway shore in this section of the monument.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall between the western boundary of the garden belonging to Apple Garth, Westfield, in the east and the dismantled railway 200m west of Westfield House in the west.

Hadrian’s Wall survives throughout this section as a buried feature. There is no evidence for the ditch to the north of the Wall, and it is likely that in this section parallel to and close to the Solway shore the ditch was not provided.

The monument includes Drumburgh Roman fort and the section of Hadrian’s Wall and its associated features between Burgh Marsh in the east and Westfield House in the west.

Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout the whole of this section. Excavations by Haverfield in 1899 located the Wall between Burgh Marsh and Drumburgh fort. The Wall measured 2.95m wide and the wall ditch was 8.9m wide and lay 8m north of the wall. Excavations by Charlesworth in 1973 confirmed the course of the Wall north of Glasson. Geophysical survey has also located the line of the Wall or wall ditch to the north east of Glasson.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has not been confirmed in this section. It is expected to run parallel to the course of the Wall set back a few metres to the south.

Evidence suggests that Hadrian’s Wall did originally pass through the Burgh Marsh to the east. No remains however have been identified here and hence this area is not included in the scheduling.

Investigation

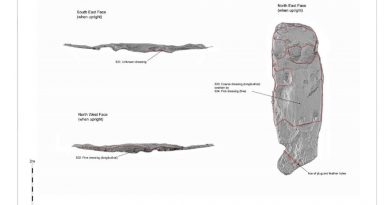

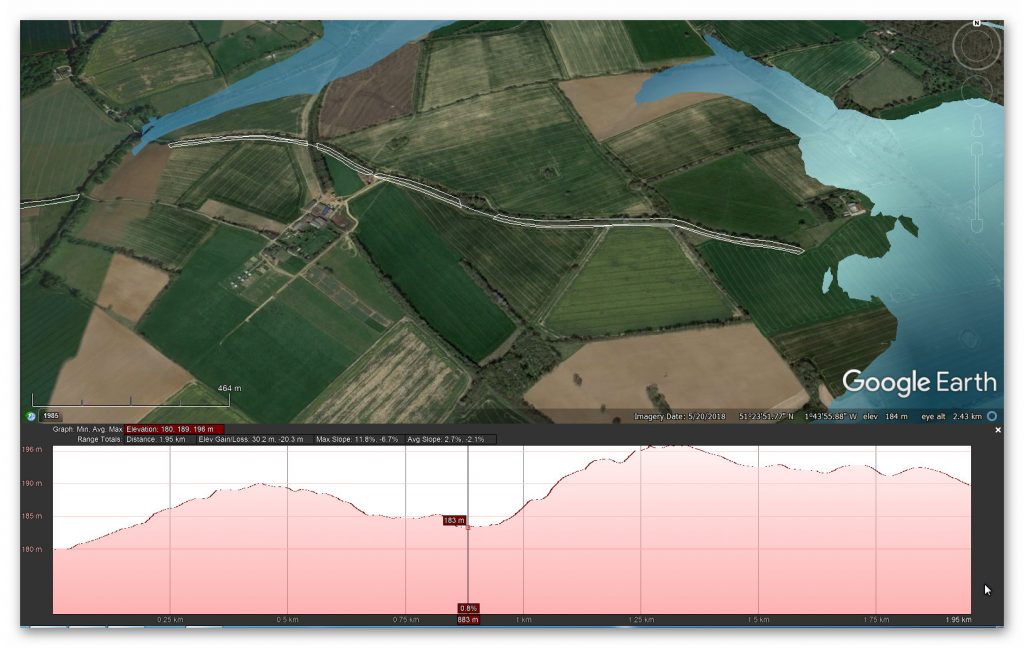

Did the Vallum just end or did it turn west as indicated by LiDAR?

If we look at the crop marks from a satellite shot (from 1985) of the termination point of the Vallum, we see it west and continues in the ground connecting to a line of field boundaries – which leads to a Paleochannel.

This turn would not offer any military advantage, but the size and direction of this channel would suggest that it was a prehistoric linear feature that became the start of the Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall.

Analysis of the Wall alignment compared to the Vallum is strange and can be only explained by a variation in the River level during the Roman period. If we raise the water level of the River Esk – then we see the wall aligns with a higher water table (8m) during this construction period.

It should also be noted that the Vallum did not at any stage run to the end of the landscape like the Wall. This could be because it connected to a Paleochannel some 3000m before the river

Was the Wall built to the edge of the Roman River Shoreline?

The existing line of Hadrian’s Wall to the North of this section shows that there is substantial land after the current shoreline of the River Erk. This makes no strategic sense as it would allow invaders to land and gather to attack the wall. Building the wall on the river’s shoreline would make much more sense.

Consequently, the current shoreline shows that Post-Glacial Flooding was still active even within the Roman Period just two thousand years ago raising the shorelines of all rivers in Britain.

This was an extracts from the NEW Book Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – The Vallum available on Amazon as a FULL COLOUR HARD BACK (£49.95) or a ECONOMY (£9.95) SOFTBACK black and white VERSION – it is also available as a KINDLE (£2.99) book. For further information about our work on Prehistoric Britain visit our WEBSITE or VIDEO CHANNEL.

Product details

- ASIN : B0BJCCMRHZ

- Publisher : Independently published (9 Oct. 2022)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 477 pages

- ISBN-13 : 979-8357147745

- Dimensions : 15.24 x 2.74 x 22.86 cm

- Illustrations 360+

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.