Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

Introduction

Promotional Video – Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke Part VI

Extract From Book……………………… Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke

The enigmatic Wansdyke, standing prominently in the Wiltshire landscape, has forever captivated the public’s collective imagination. Its proximity to the famed ancient site of Avebury, with both bearing massive ditches, has led some to surmise a direct connection between them.

Curiously, past and present archaeologists have failed to grasp this apparent link, striving instead to find a simplistic explanation for this enigmatic “linear structure.” Thus, the prevailing belief took root – that it was a bulwark raised to repel the belligerent tides of yore. Consequently, the term “Saxon” was affixed to these earthworks, as historians of old supposed these “tribes” possessed the martial might needed to accomplish such grand engineering feats to defend their realm.

Yet, in recent decades, this “fact” has faced reexamination, and a novel theory emerged regarding these earthworks as “Boundary Markers” etched upon the landscape. This alternative proposition, while reassuring, still leaves us grappling with perplexing truths. Foremost among them is the Dykes’ lack of continuity – both Wansdyke and Offa’s Dyke exhibit sizeable lacunae in their stretches. Their beginnings and endings emerge with an almost magical quality, unexplained and confounding to the beholder.

Moreover, if indeed these were markers of territorial ownership, then why do certain Dykes, like Offa’s, follow paths that traverse vast separations, such as major rivers? Surely, a more conspicuous landmark than a mere 4-meter ditch would have served as an apt boundary in such instances.

Alas, the erudite scholars of archaeology have turned a blind eye to the existence of over 1500+ scheduled Dykes scattered throughout Britain and Ireland. Such a multitude challenges the notion of a uniform purpose, as many of these “boundary markers” also graced uninhabited islands far and wide, enveloping the entire circumference of Britain.

In the spirit of Jacob Bronowski’s method, we must confront these enigmas with a relentless curiosity, unearthing each fragment of evidence and subjecting our suppositions to rigorous scrutiny. The mysteries of these ancient earthworks shall only yield their secrets to those intrepid minds that dare to question and challenge the established norms of interpretation. And as history unfolds its layers, we may find ourselves ever closer to unlocking the profound meaning behind these age-old constructs that once shaped the course of human existence upon this storied land.

Robert John Langdon (2023)

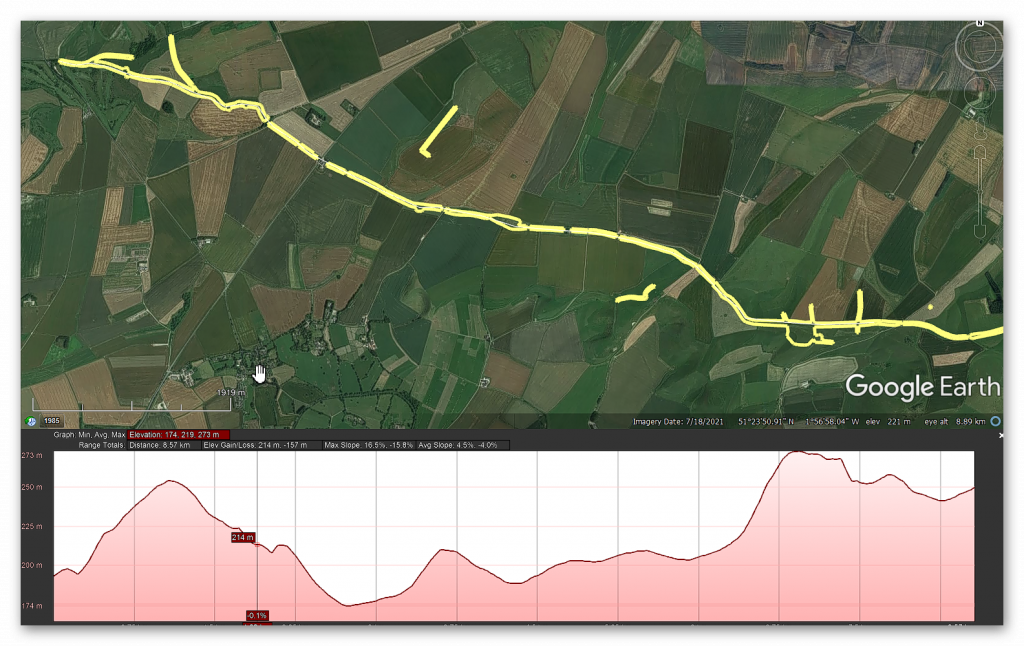

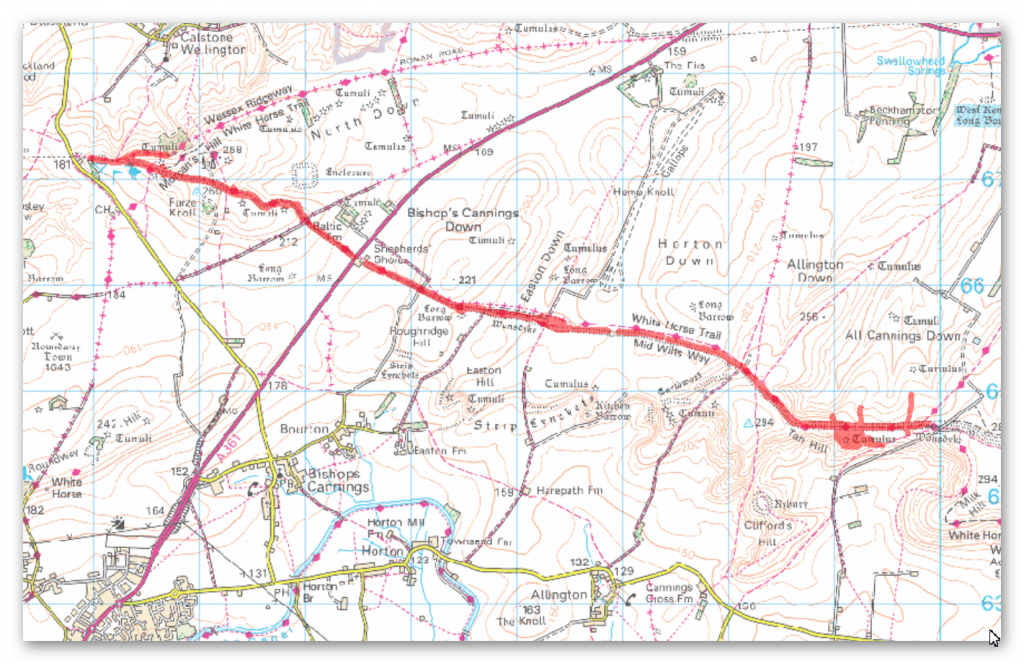

Section 4 – HE:1017288

Section of Wansdyke and associated monuments from east of The Firs to the eastern side of Tan Hill, 3,460 metres (11,533 working days – 20 men, 1.58 years)

OS Map

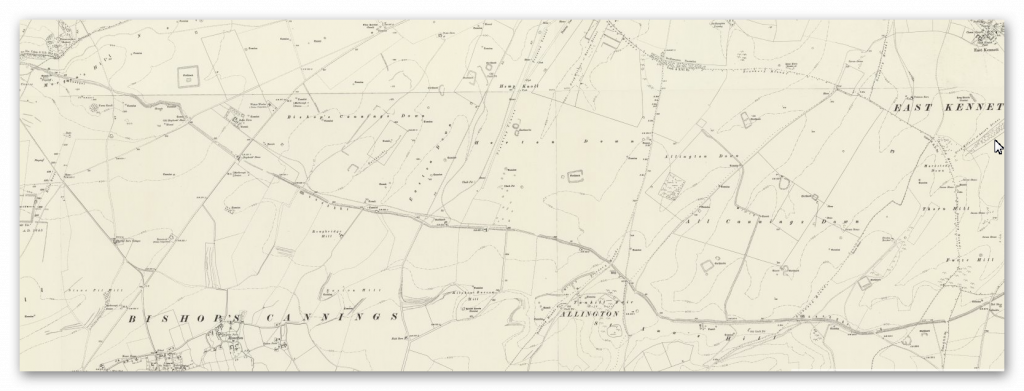

1800 Map

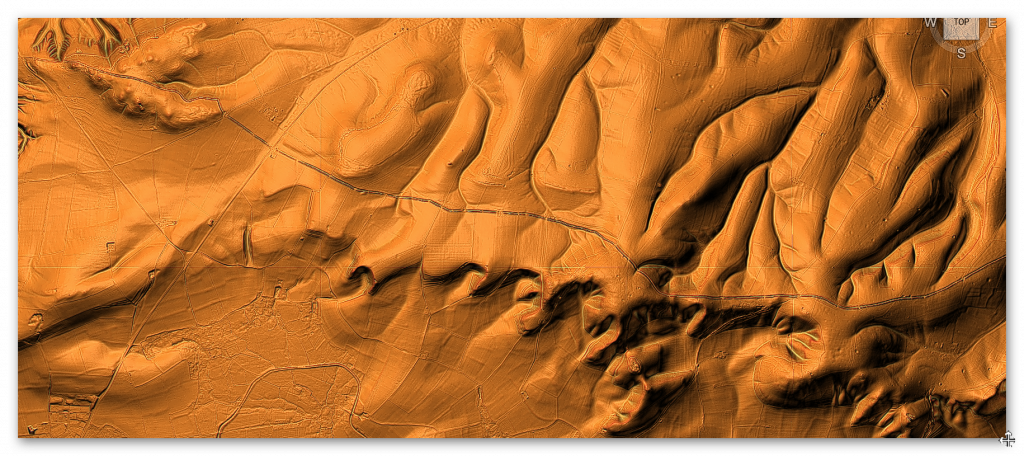

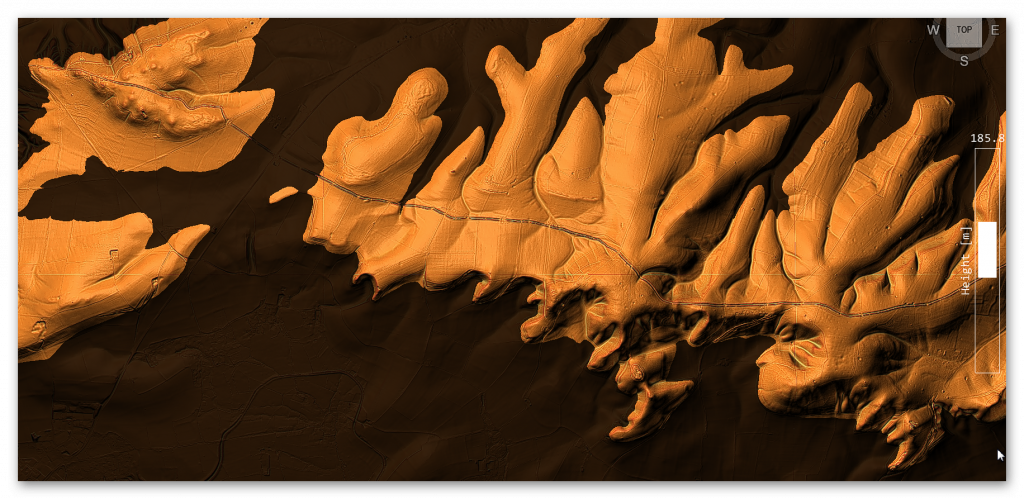

LiDAR Map

LiDAR Map (with Mesolithic water levels)

HE schedule suggests that:

The monument, which falls into 12 areas of protection, includes part of Wansdyke running from east of The Firs to the eastern side of Tan Hill,(a kite-shaped enclosure situated on the northern side of Wansdyke on Easton Down), a section of Roman road on Morgan’s Hill, a Neolithic long barrow, five other linear earthwork sections crossed by or abutting the Dyke and 11 Bronze Age bowl barrows adjoining Wansdyke or partially overlain by it.

From the west, Wansdyke runs for roughly 72km ending just outside Marlborough at its east end. The approximately 8.5km long section from east of The Firs to the eastern side of Tan Hill runs across the Downs south west of Avebury and includes the best-preserved continuous length of Wansdyke.

The Dyke includes a substantial earthwork bank which measures up to 30m wide and stands from 1m to 3m high. For the majority of its length the bank lies south and west of a substantial open ditch. This also varies in width but measures up to 36m wide and remains open to a depth of 2m in places.

The majority of the bank and ditch sections in this area together measure from 30m to 40m across. A further, slighter, bank beyond the ditch to the north is also visible on several sections. The Dyke was built in sections of varying length, with breaks which would have allowed controlled traffic to pass from east to west and for the movement of military patrols beyond the defences. The Dyke is later in date than the Roman road but was already built by the mid-ninth century, when it is mentioned in a Charter.

It is generally believed to be a military frontier work between Wessex and Mercia. It is designed to hold the edge of the high ground on the Downs and to protect the lower lying plains to the south west. The name derives from Woden’s Dyke, after Woden, an important Anglo-Saxon god whose name survives in the word `Wednesday’.

The earlier Roman road includes a 800m long section of the route from Cunetio (Mildenhall) to Verlucio (Sandy Lane). It runs east to west along the north slope of Morgan’s Hill and includes a rare engineered bend at the head of a dry valley after which point the later Dyke meets it and runs along its line. The road measures between 8m and 10m wide and its outer (north) edge comprises a well-constructed embankment which stands up to 2m high.

The road is terraced into the slope at this point and the Dyke follows the line of the road for a distance of over 300m. South east of the wireless station on Morgan’s Hill, a 50m long, slightly curved section of linear earthwork runs north from beneath Wansdyke to end in a terminal. It is part of a longer feature, the remainder of which starts about 20m north, runs to the edge of Horsecombe and is the subject of a separate scheduling (SM 21900).

The south end of this feature is not known for certain but it appears to run beneath the Wansdyke for some distance to the east. Immediately south of the Dyke on Roughridge Hill is a Neolithic long barrow. The barrow mound measures about 75m long and up to 32m wide. It stands up to about 1m high. Flanking the mound, but no longer visible at ground level due to the spreading of the mound caused by ploughing, are two quarry ditches which will survive as buried features.

Although the only example in the scheduling, the barrow is one of a line of more than four Neolithic long barrows which are strung out east to west along the ridge of the Downs, all spaced roughly 1km from their nearest neighbour in either direction.

The excavations showed that the southern boundary of the enclosure lies below the line of the later Wansdyke, which appears to change course slightly at this point. The excavations also produced Romano-British pottery sherds from the interior of the monument, indicating that it was a settlement during that period.

The section of Wansdyke on Tan Hill crosses a series of four earlier linear boundary ditches which form part of an earlier prehistoric land division. Three of these run from north to south and the last runs east to west and is abutted by at least one of the others. These boundaries survive as buried features clearly visible on aerial photographs and, despite being levelled in places, remain visible at several points above ground. The ditches vary in width from 3m to 8m across and several have adjacent banks about 0.75m wide and up to 0.3m high.

Together they form three sides of a rectilinear field within which is located a small Bronze Age barrow cemetery containing five bowl barrows. Two of these are partially overlain by the Wansdyke. The barrow mounds measure from 12m to 20m in diameter and stand between 0.2m and 1m high.

All but one of these are surrounded by quarry ditches which vary from 1m to 2m in width and survive buried below the present ground level. There are six further bowl barrows along the length of Wansdyke from east of The Firs to the eastern side of Tan Hill which are partially overlain by the Dyke. Some of these are outliers of groups of barrows or cemeteries, the remainder of which, where appropriate, are the subject of separate scheduling’s. These barrows vary from 10m to 20m in diameter and stand up to 3m high. Their surrounding quarry ditches measure from between 1m to 2m wide.

Several barrows near to Old Shepherds’ Shore were partially excavated in the 1850s and finds included burnt animal and human bone and fragments of Bronze Age pottery.

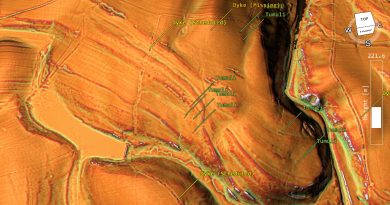

| Figure 34 – Paleochannel from the Raised Water Levels of the Mesolithic meet the Dyke |

| Figure 35 – Ditch cutting through the Dyke at 90-degrees |

In the scrolls of history, the unveiling of Fig.35 beckons us to peer beyond the veil of conjecture. Perhaps the compass that navigates us through the labyrinth of whispered questions through the corridors of time lies here. Once an enigma shrouded in uncertainty, the Dyke unfurls its narrative in North and South, a juncture marked by division and unity.

Yet, as we stand at this crossroads, the questions persist. What grand design does this divide mark? Is it a sentinel of boundaries or a symphony of defence? Why does the Dyke, an embodiment of strength, pause just a breath away from spanning both directions? What landscapes, what treasures, do these truncated extensions seek to shield?

The visage of paleochannels, ancient waterways etched in the very fabric of the land, presents itself as a canvas of revelations. LiDAR’s eye, attuned to the wavelengths of discovery, showcases the embrace of Wansdyke’s ditches with these prehistoric conduits. In their intersection, a portrait emerges—a depiction of a junction, a crossroads where not just land but waterways merged.

The resonance of this image is profound. A Dyke, often considered an embodiment of solidity, now intersects with the fluidity of these forgotten watercourses. This confluence hints at more than coexistence—it suggests a portal, a point of ingress and egress, a thoroughfare not merely for terrestrial travellers but also for vessels that rode the liquid highways.

Such a revelation prompts us to reconsider the dike’s identity. Could this monumental construction, both a bastion of earth and a harbour of history, be conceived not solely for defence but as a connection conduit? An edifice that channelled both earthly aspirations and the currents of culture, bridging the realm of humans and the dominion of water?

| Figure 36 – GE Map shows deep ditches which are now paths going across the Wansdyke |

The southern reaches unfurl a tale of depth and mystery—a narrative that extends beyond the bounds of Wansdyke’s familiar embrace. Here, etched upon the land like whispers of the past, are deep cuts that time has adorned with the patina of ages. Now trodden as footpaths, these cuts reveal themselves as gateways to antiquity, as portals through which we traverse history’s corridors.

Yet, the panorama holds another surprise—a forgotten ditch, an enigmatic excavation that defies the confines of historical schedules. This ditch, absent from Historic England’s scrolls, surrenders itself to the embrace of an old Paleochannel river, like an echo reverberating through time. Fig. 36 becomes a tableau of continuity, a link between the tapestries of yesteryears and the present.

| Figure 37 – Paleochannels connecting to Wansdke |

In this interplay of cuts, ditches, and ancient rivers, a question arises—what hands sculpted these channels, and what intentions propelled them into existence? Were these marks of human endeavour borne from a need to navigate the landscape, to forge paths that transcended the eras? Or are they the product of a deeper design, etched by nature herself and embellished by the curious hands of humans?

As we meander through the corridors of speculation, let us remember the canvas of history is not confined to the visible, the documented. It expands, much like the very rivers and footpaths that traverse it, into the realm of the unseen and the uncharted. In the echoes of these cuts, in the absence of recognised schedules, we find a reminder that history is a symphony of the known and the unknown, a dance that transcends temporal confines.

In the mosaic of history, Fig.37 casts a spotlight upon a revelation that bridges epochs and echoes with the very essence of the land. Here, amidst the tapestry of ancient landscapes, emerges the presence of monumental sarsen stones, sentinels of time, scattered as relics of the ages in the embrace of the Paleochannels.

| Figure 38 – Paleochannels everywhere some showing sarsen stones in the dry river valley indicating the size and strength of these old rivers – first edition OS. |

These stones, witnesses to the drama of ice and thaw, lay scattered as if nature herself crafted an intricate mosaic. The legacy of the last Ice Age is etched upon them, a testament to the forces that shaped this realm long before the footfalls of humankind. As the old OS maps bear witness, these stones, abundant in the embrace of the Paleochannels, evoke a tale of glacial might and the enduring memory etched upon the land.

| Figure 39 – The ‘Unknown’ditch heads north and then kinks |

A profound realisation emerges in this dance of discovery—a symphony of logistics and ingenuity unfurls. If these sarsen sentinels were to be harnessed and woven into the fabric of human endeavour, the waterways would have served as a celestial highway, a course of least resistance. And in this tableau, Wansdyke emerges not only as a Dyke, not merely a demarcation or defence, but as a lifeline that harnessed the power of water to serve human ambition.

In the intricate mosaic of historical discovery, the enigmatic ditch takes centre stage once more—a whispered riddle etched into the landscape. It meanders through the pages of time, seemingly wandering aimlessly, a question mark in the grand narrative. Yet, as we sift through the fragments of history, a revelation shimmers into view that bind the ditch and the very fabric of prehistory.

| Figure 40 – The ‘unknown’ Dyke links to the Kennet River that goes to both Avebury and Silbury Hill |

As modern OS maps render this ditch a ghost upon the terrestrial canvas, the marriage of technology and imagination unveils the hidden treasure. LiDAR’s touch, a modern conjurer’s wand, weaves the paleochannels and prehistoric shorelines into the mosaic. In this dance of data emerges a connection that defies the constraints of eras—a direct link between the ditch and the hallowed grounds of Avebury and Silbury Hill.

This revelation echoes through time, whispering that these ancient sites, Avebury and Silbury Hill, are not merely isolated islands but interwoven threads of a grand tapestry. The ditch, a seemingly solitary enigma, reveals itself as a connective vein—a corridor of history that flows not to obscurity but to monumental sites that have stood sentinel through the epochs.

This conjured connection, a bridge between Wansdyke and Avebury, paints a canvas where history transcends the confines of linear progression. It offers a vision of prehistory as a symphony of parallel stories, where Wansdyke and Avebury, once disparate entities, become harmonious notes that resound across the landscape. The notion that they were born simultaneously, intertwined in a narrative of ambition, culture, and design, is a testament to the shared aspirations of humanity across time.

Roman Water Management

| Figure 41 – Small right-angled addition to the Dyke – but for what practical reason |

| Figure 42 – Cross Regulator – water management system |

In the annals of historical inquiry, the tiny Dyke that extends from Wansdyke assumes a posture of intrigue—a whispered question mark punctuating the landscape. In its modest form, it beckons us to decipher its purpose, to unearth the intentions woven into its design. As we traverse the realm of speculation, two threads of possibility unfurl, each offering a glimpse into the minds of those who shaped it.

One narrative paints the Dyke as a haven, a berth upon the liquid highway—a stop for boats, a safe harbour for those who navigated the waters the dike embraced. In this vision, the Dyke transforms into a passage not solely for people and stones but for the vessels that threaded waterways laden with cargo, hopes, and history. The “parking feature” becomes a tableau of respite—a moment of pause in the voyage of time.

In this incarnation, the Dyke assumes a role akin to a conductor’s baton—a water regulator orchestrating the flow of springs that may have danced through the landscape. A “Cross Head Regulator” from the annals of modern canals whispers through time, suggesting a parallel with the water management systems of the Romans, as glimpsed in the scrolls of history at Hadrian’s Wall.

The contemplation of Roman engineering and its influence upon the Dyke reflects the epochs’ interconnectedness. The Romans, architects of both empire and innovation, are known to have left their indelible mark upon the landscapes they traversed. Could this diminutive Dyke be a remnant of their water management techniques, a testament to their mastery over the elements as seen in other corners of the realm?

Rybury Camp and Tanhill Fair

| Figure 43 – Tanhill Fair – complex earthworks showing Rybury Camp on the peninsula |

The woven tapestry of history, the complex series of ditches extending from Wansdyke casts a net of intrigue and speculation. Their intricate dance, flowing down into the Dry River Valley, unveils a terminal that might have been a hub of significance—a nexus where the threads of trade and human interaction converged. This vista hints at a site not solely dedicated to defense or marking, but a junction that pulses with the rhythm of exchange.

Through the corridors of time, the echoes of Tanhill Fair reverberate. As if in a symphony, the words of Aubrey from the 17th century whisper of a fair held within an “old camp,” summoning images of bustling marketplaces and vibrant commerce. This isn’t a mere snapshot in history; it’s a snapshot of continuity—a legacy of trade that spans from Medieval times to the annals of antiquity.

| Figure 44 – Tanhill Fair showing a supplementary ditch that connects to Wansdyke in two places and goes down into the river valley (GE) |

| Figure 45 – The Dyke seems to vist two quaaries before getting to Wansdyke |

| Figure 46 – OS map shows the remains of the ditches went from the Paleochannel (in the Valley) to Wansdyke |

Pic 45, like a palimpsest, unfurls before us—a visual odyssey that belies the limits of schedules and registers. The ditch works at Tanhill Fair reach far beyond their documented bounds, stretching both directions and connecting in two places to Wansdyke. This revelation is a testament to the fluidity of history, a reminder that the boundaries we impose upon the past are but a sliver of the stories that await our exploration.

In the theatre of interpretation, a bold hypothesis emerges—the possibility that these ditches, these conduits carved into the earth, were not mere markers or barriers but lifelines of trade. A canal, a passage through which boats might have threaded their way, carrying treasures, aspirations, and cultures from distant corners of the known world. This vision unites Wansdyke and Tanhill Fair not as separate entities but as partners in the choreography of history.

| Figure 47 – Tan Hill and Rybury Camp as a Peninsula in the Mesolithic |

Roman Road joining two Dykes

Morgan’s Hill is close to a crossroads of revelation—an unassuming stretch of the Dyke that belies its significance. A linear expanse, a departure from the meandering course that defines 99% of the Dyke, captures our attention. This apparent anomaly in the landscape becomes a canvas for exploration, urging us to unveil the threads that weave its story.

A curious pattern emerges as we consult the LiDAR map and trace the hidden design drawn by the pits. Two segments along this straight stretch deviate from the norm—a conspicuous absence of the quarries and pits that have characterised the journey so far. The landscape whispers a puzzle, inviting us to decode its enigma.

| Figure 48 – The Roman Road joins two Prehistoric Dykes |

Enter the Mesolithic shoreline, a harbinger of revelation. When layered upon the LiDAR map, it illuminates a past submerged beneath the tides of time. Suddenly, the straight stretch of the Dyke unfurls its secret—it’s not merely a Roman road but a bridge that spans epochs. It joins the dots, connecting two prehistoric courses of the Wansdyke that once wove a “wibbly wobbly” path across the landscape.

This discovery is a testament to history’s interconnectedness, the symbiotic dance between human endeavour and the ebb and flow of nature. The Romans, architects of their era, harnessed these prehistoric pathways, channelling their ingenuity to connect the dots drawn by time. It is a reminder that history is not linear but a mosaic—a collage of human intent and the tides of change.

The Morgan Hill Kink

| Figure 49 – Morgan Hill East ‘kink’ |

| Figure 50 – Morgan Hill Kink’s barrows |

To the East of Morgan Hill is found a bizarre Kink in Wansdyke. This is best seen on an OS map showing this strange direction and the obstacles it avoided.

In the panorama of landscape and time, the kinks and turns of Wansdyke invite us to unravel the intentions woven into its form. As we ascend the topology of the hill, we stand witness to a sequence of choices that defy easy classification but beckon us to scrutinise their purpose.

The kinks and turns present a conundrum to the theories of fortification or marking. Their seemingly inefficient trajectory, descending the hill’s advantage and taking multiple turns, challenges the notion of defence or demarcation. From a defensive perspective, the logic of such a design raises questions about the resource and time invested.

As we tread through the corridors of inquiry, a new light shines upon the landscape—the presence of round barrows. Like sentinels of history, these ancient mounds encircle the kink on both sides. The question arises whether these barrows were built around the contours of Wansdyke or whether the kink was crafted to navigate around the barrows.

The chronicle deepens with the discovery of the missing branch—a path unmarked on contemporary maps but unveiled through Historic England’s lens. The cross ridge Dyke on Morgan’s Hill etches its presence across the east-west aligned ridge. The bank and ditch, sculpted by time’s hands, become conduits of understanding, the stories they tell interwoven with the landscape.

Branch off Wansdyke

The monument includes a 560m long section of a Cross ridge Dyke situated on Morgan’s Hill. The Dyke runs from NNW to SSE across the east-west aligned ridge, dividing Morgan’s Hill into two parts. The Dyke has a bank c.8m wide and up to 1.5m high. To the East of the bank lies an 8m wide ditch which provided material for its construction and enhanced the effectiveness of the boundary.

This has been partly infilled by cultivation but is open to a depth of 0.3m in places, and is visible on aerial photographs. The bank and ditch are interrupted by a number of openings through which animals and people could pass. It is not clear how many of these are original.

A further section of the Dyke, situated to the south is crossed by the Wansdyke, which is later in date. This additional section is the subject of a separate scheduling. Excluded from the scheduling are the post and wire fences which cross it and run along its length, although the ground beneath is included. – English Hertitage

| Figure 51 – Branch off Wansdyke |

In the intricate tangle of time and earth, the convergence of the Cross-ridge Dyke on Morgan’s Hill and the enigmatic Dyke of East Wansdyke draws us into a narrative of layered history. Their banks and ditches, the silent architects of the landscape, weave a tale of coexistence, connection, and perhaps even evolution.

These two Dykes, mirroring each other across time and the contours of the land, embody a dialogue between epochs. Their unity atop Morgan’s Hill, a meeting point that defies temporal confines, reminds us that history is not merely a linear march—it’s a dance that spans centuries, uniting hands that have shaped the earth.

The paleochannel’s passage through the Dyke carries echoes of ancient currents—a testament to a time long before the Dyke’s construction. This fragment, missing as if eroded by the tides of prehistory, whispers that the roots of this land stretch further than the architects who shaped it. This gap in the Dyke is a tapestry of continuity, a reminder that even the most monumental structures stand atop layers of untold stories.

| Figure 52 – Morgan’s Hill West with another Branch |

The saga of East Wansdyke’s creation offers a riddle unto itself. The builders, crafting their work across chalk, kept the earth they excavated to one side. This pragmatic choice of preserving the turf for stability and camouflage echoes a nuanced purpose. It becomes evident that these Dykes are not mere boundary markers or defensive structures. They are more—a marriage of utility and adaptation, a testament to human ingenuity and the intersection of practicality and aesthetics.

| Figure 53 – Junctions heading north off Wansdyke past a group of Round barrows |

The view northward, captured in Fig. 53, extends the tableau of discovery. Like a palimpsest, the landscape bears the imprints of Wansdyke’s journey. It dances alongside the Roman Road, a chorus of human footsteps interweaving through time. The round barrows and raised river shorelines, silent witnesses to centuries past, reaffirm the interplay of cultures, constructions, and course changes that define human endeavour across epochs.

| Figure 54 – How Morgan Hill used to look in the Mesolithic – with the roman road towards the bottom turning left (North) |

Chronology (Smoking Gun)

In the ongoing dialogue with history, a revelation emerges—wrought from the very contours of the land, an ancient pathway unveils its secrets. The Roman road, a trail of human ambition etched across the landscape, weaves its course atop the pages of Wansdyke’s story. This intersection, where road and Dyke converge, is a testament to the interplay of cultures, epochs, and purpose.

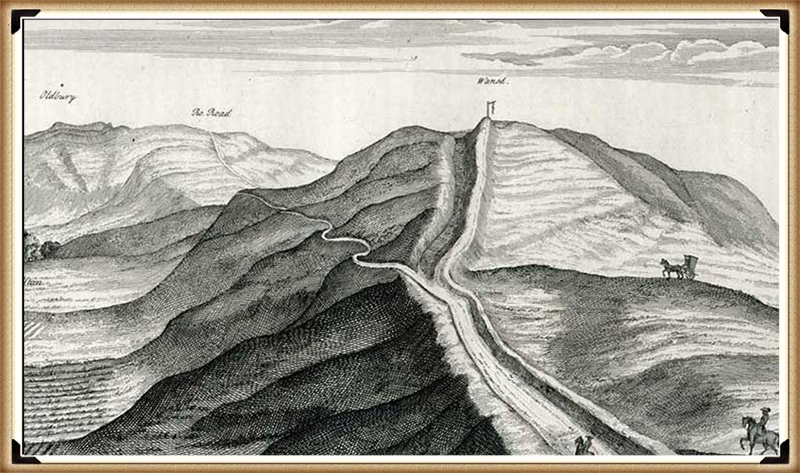

Stukeley’s drawing on Page 6, Fig.24, long questioned by the annals of archaeology, finds newfound validation through the lens of LiDAR—a digital conjurer that unveils hidden truths. Once doubted as an exaggeration, the cut through the bank now emerges as a footprint in time. LiDAR’s gaze, untethered by perception’s limits, reveals that this cut bends in harmony with the Roman deviation, a harmony of intent that speaks of chronology.

| Figure 55 – Roman Road cuts through Wansdyke making it older! |

The alignment of the Roman road, cleaving through the very heart of Wansdyke’s bank, resonates with the echoes of purpose. This road, a conduit for the aspirations of the Roman era, tells a tale of connection and coexistence—an acknowledgement that the landscape’s past holds layers that intertwine like the fabric of time itself.

The chronicle of Wansdyke, interwoven with the path of the Roman road, unveils a narrative that spans millennia. This intersection becomes a bridge that invites us to traverse the epochs and honour the efforts of hands laboured to craft earthwork and thoroughfare. It becomes a gateway that prompts us to unravel the threads of intention, the dance between cultures, and the pulse of human progress.

The application of LiDAR technology has decisively resolved the inquiry. LiDAR data reveals a cross-sectional embankment profile mirroring the Roman roads deviation’s curvature, indicating the roadway’s construction postdates the Wansdyke earthwork.

This LiDAR evidence serves as a compelling confirmation of prehistoric Dyke dating, akin to a “smoking gun.” LiDAR employs laser reflection and time-of-flight measurements to gather precise topographic data by emitting and measuring laser pulses. This technology’s congruence with historical context validates its role in archaeology, exemplifying how modern tools can illuminate ancient landscapes.

The Book

This was an extracts from the NEW Book Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke available on Amazon as a FULL COLOUR HARD BACK (£19.95) or a ECONOMY (£4.99) SOFTBACK black and white VERSION – it is also available as a KINDLE (£1.99) book. For further information about our work on Prehistoric Britain visit our WEBSITE or VIDEO CHANNEL.

Product details

- ASIN : B0BF31GQKC

- Publisher : Independently published (18 Sept. 2022)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 134 pages

- ISBN-13 : 979-8353488897

- Dimensions : 15.24 x 1.3 x 22.86 cm

- Illustrations: 85

- Customer reviews: 5.0 out of 5 stars 1 rating

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth - Prehistoric Britain