Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

Extract from the Book ‘Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries)

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 1. Pigments

- 3 2. Copper

- 4 3. Tin

- 5 4. Gold

- 6 5. Lead

- 7 6. Silver

- 8 7. Zinc

- 9 8. Iron

- 10 9. Coal

- 11 10. Oil Shale

- 12 11. Peat

- 13 12. Jet

- 14 13. Amber

- 15 14. Flint

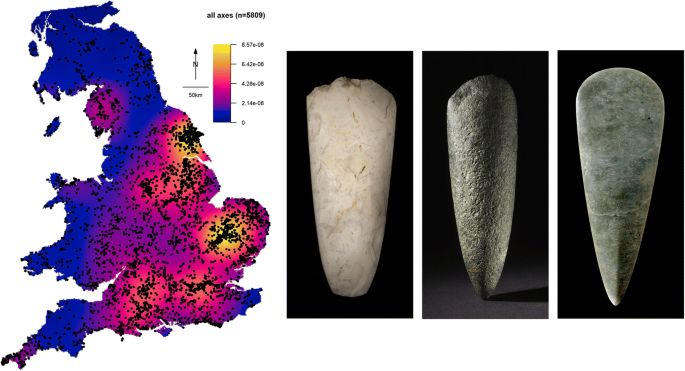

- 16 15. Polished Stone Axes

- 17 16. Building Stone

- 18 17. Ornamental Stone

- 19 18. Limestone

- 20 19. Quernstone

- 21 20. Clay

- 22 21. Salt

- 23 Further Information

- 24 Other Blogs

Introduction

- Mineral Pigments

- Copper

- Tin

- Gold

- Lead

- Silver

- Zinc

- Iron

- Coal

- Oil Shale

- Peat

- Jet

- Amber

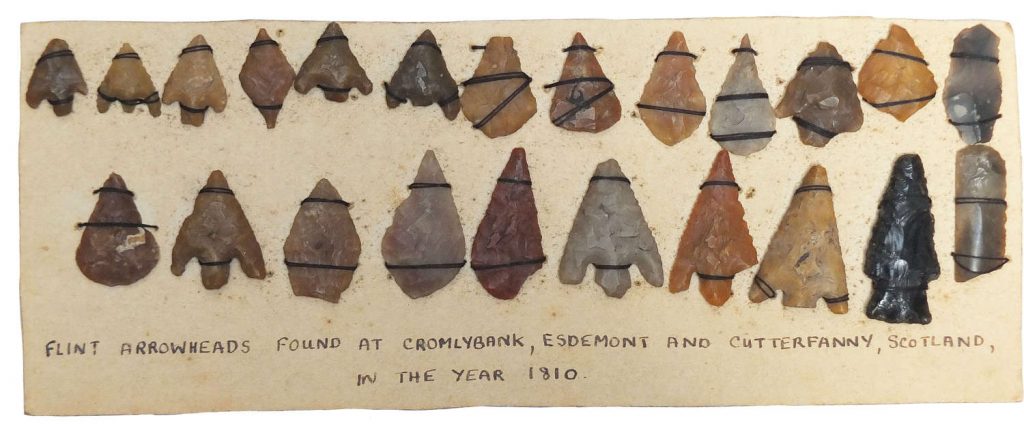

- Flint

- Polished Stone Axes

- Building Stone

- Ornamental Stone

- Limestone

- Quernstone

- Clay

- Salt

Conclusion

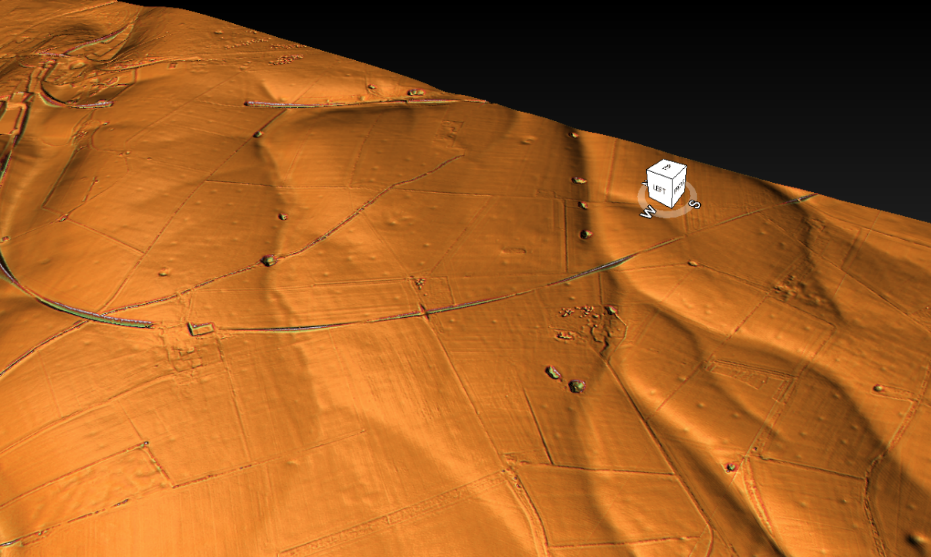

In the captivating pursuit of unearthing the secrets of our island’s prehistoric history, our extensive mapping and research endeavours have unveiled a fascinating dimension previously unexplored. Utilising cutting-edge LiDAR technology, we have revealed a complex network of Dykes, Linear Earthworks, and Hill Sites—archaeologically recognised as hill forts and causewayed enclosures. These enigmatic structures provide valuable insights into the ancient landscape, shedding light on the activities of our ancestors as they engaged in the extraction, transportation, preparation, and trade of raw mined materials.

The enigma that now grips our attention is profound: What drove ancient humans to erect such impressive engineering structures and enduring wonders? As we delve deeper into the archaeological record, we are fueled by the quest to comprehend the forces that shaped these remarkable landmarks.

The discovery of these engineering feats has sparked a sense of wonder and curiosity about the motivations that guided the lives of our prehistoric forebears. The sourcing and processing of these raw materials held immense significance in the socioeconomic dynamics of ancient societies. Establishing intricate hill forts and causewayed enclosures signifies a complex resource exploitation system and trade networks that span vast distances.

We endeavour to unravel these raw materials’ mysteries through rigorous archaeological analysis. We aim to identify their geological origins, discern the extraction methods employed, and understand the technological prowess required for their preparation. Furthermore, we seek to grasp the cultural significance of these materials, as evidenced by their use in the construction of monumental earthworks and awe-inspiring structures.

Our pursuit of understanding is not solely driven by scientific curiosity but also by the conviction that studying these materials is vital to unlocking the secrets of our ancestors’ lives and societies. Preserved within the fabric of the landscape, these materials serve as tangible remnants of ancient human endeavours, providing a unique window into the distant past.

As we continue our archaeological investigations, we approach the task with humility and a profound realisation that the ancient world was a realm of intricate interconnections and complex interactions between humans and the environment. Our meticulous research aims to foster a deeper appreciation for our prehistoric predecessors’ ingenuity and resourcefulness and shed light on their actions’ profound cultural and social implications.

In the face of these awe-inspiring monuments and enigmatic sites, we marvel at the resilience and creativity of ancient humans, who, millennia ago, left an indelible mark on the landscape—a mark that continues to captivate and inspire us to this day. With reverence for the past and an unwavering commitment to unravelling its mysteries, we acknowledge that each discovery serves as a stepping stone toward a more profound understanding of our shared human heritage.

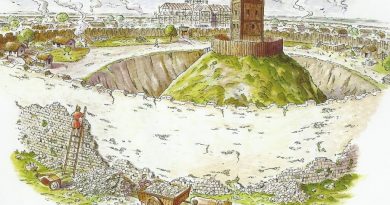

Scowles

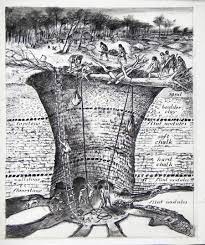

In the fascinating pursuit of unveiling the secrets hidden within the British landscape, the extraordinary LiDAR surveys have revealed a multitude of scattered pits, entwined with the enigmatic features of Dykes, Linear Earthworks, Hill Side sites, and Earthworks. Yet, the true essence and purpose of these enigmatic pits continue to challenge the curious minds of the archaeological community. Previous excavations and speculative interpretations have offered but a glimpse into their potential ritual and ceremonial significance, leaving us yearning for deeper understanding. Among these captivating pits, one intriguing type, nestled in the heart of the Forest of Dean in Gloucestershire, England, has captivated the attention of investigators.

Traditionally, the Scowles were perceived as remnants of ancient open-cast iron ore extraction, tracing their origins to the early historic eras. However, the intrepid Forest of Dean Archaeological Survey research dares to challenge this perception, proposing an alternative narrative. According to their audacious proposition, the genesis of these peculiar formations lies predominantly in the arms of nature, moulded over aeons, and later embraced by human endeavours.

The genesis of Scowles unfolds over millions of years, a grand tapestry woven around geological outcrops of Carboniferous limestone and sandstone. Deep underground, ancient cave systems took shape, where iron-rich waters from the central Forest area bestowed their treasures upon the crevices, delicately depositing iron ore within.

Through the ceaseless dance of erosion and uplift, these once-secretive caves emerged into the daylight, revealing themselves as deep hollows and exposed rock formations. In the intimate context of the Forest of Dean, this geological tale finds its harmony, but the riddle deepens as we confront the widespread occurrence of akin pits across the vast expanse of Britain.

Wansdyke shows the same pits by prehistoric Paleochannels.

In the age of Iron and Roman empires, the discerning gaze of humanity beheld the hidden treasure concealed within the rugged countenance of Scowles. With sagacity and determination, they delved into mining activities, extracting the precious iron ore destined for the transformative flames of smelting and eventually gracing the world in trade and utility. Regrettably, the passage of time, with its inexorable hand, has obscured direct evidence, rendering the exact dating of this exploitation an elusive pursuit thwarted by the constraints of resources and funding.

The very term “Scowle” is adorned with linguistic charm, bearing traces of its origin in the ancient Brythonic tongue, where “crowll” whispers of a cave or hollow, or perhaps the Welsh “ysgil,” hinting at a recess. The echoes of a bygone era resonate through language, offering a fragment of the tale that once unfolded amidst these natural wonders. Yet, despite the strides made in discerning the natural genesis of Scowles and their intriguing human connections, the overarching enigma pervades. The broader distribution and the precise historical context of these pits, scattered across the tapestry of Britain, continue to defy definitive explanation, beckoning us to embark on an intrepid journey of investigation and inquiry.

We stand humbled by the enigmatic mysteries etched upon our land. Each revelation entices us to explore further, to reach beyond the frontiers of knowledge, for it is in the relentless pursuit of understanding that the light of enlightenment shines brightest. As we traverse the hidden passages of time and delve into the heart of the Earth, may our quest for knowledge illuminate the shadows of the past, painting a vivid portrait of the ancient world and its indomitable spirit. With awe and wonder, we gaze upon the Scowles, an enduring testament to the intertwining of nature’s artistry and humanity’s inquisitive spirit.

Non-ferrous Metals

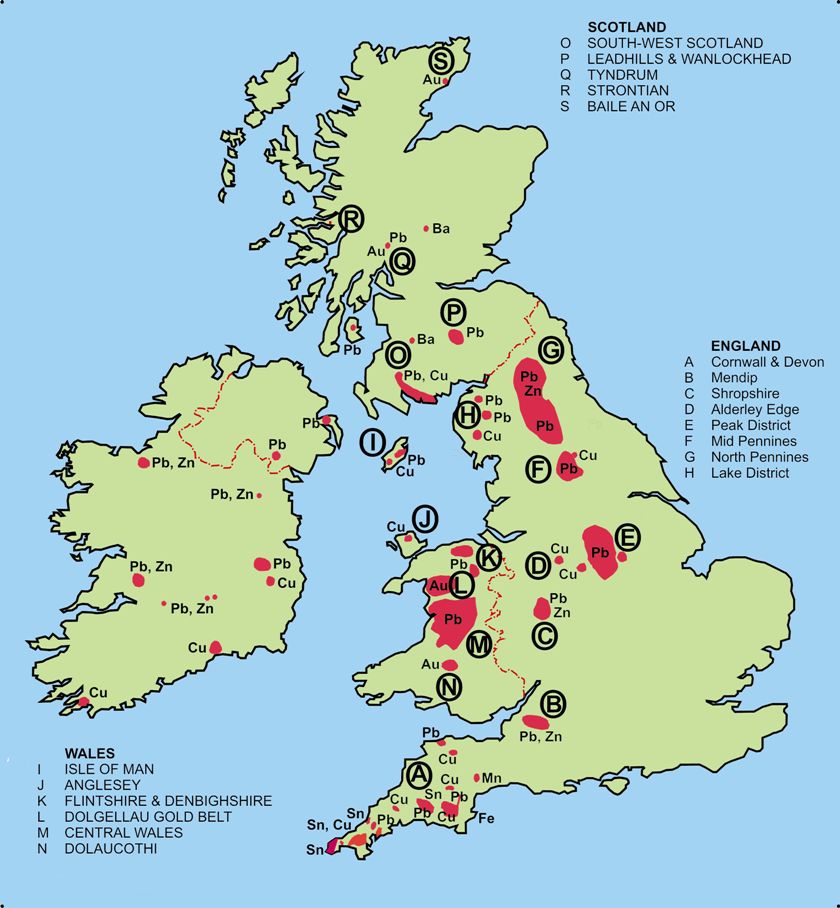

Prehistoric Copper Mining in Britain: Since the late 1980s, archaeological research has focused on prehistoric copper mines in Britain, particularly in Wales. Twelve sites dating to the Early Bronze Age have been discovered and excavated, with significant publications.

Mining Techniques and Materials: The prehistoric miners worked with mixtures of oxidised sulphidic ores, including chalcopyrite, malachite, and others, often mixed with galena in surface oxidised zones of vein deposits. They used methods such as firesetting and the use of bone or antler picks, and a collection of hafted and hand-held stone tools.

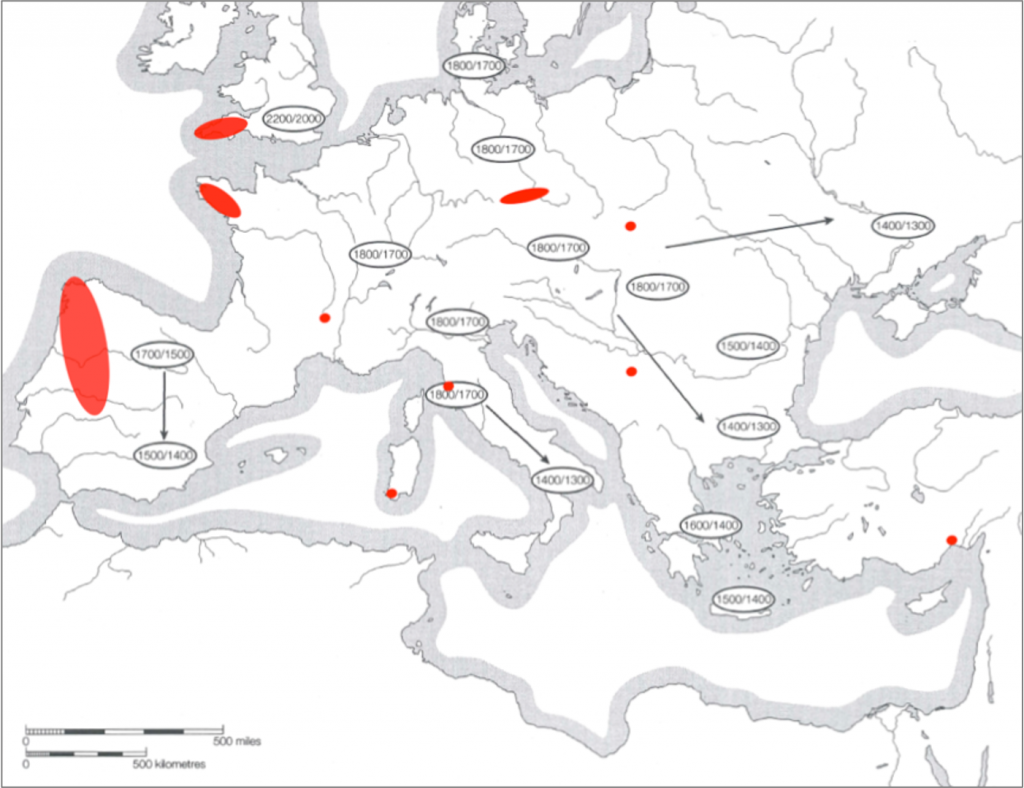

Chronological Progression of Copper Mining: The exploitation of copper resources in the British Isles is believed to have started around 2400 BC in SW Ireland at the Ross Island mine. After depletion, the search for new copper resources moved to sites in southwest Cork, the Isle of Man, and then the west coast of Britain, particularly in the mid-Wales uplands.

Abandonment and Prospection: By 1600-1500 BC, most of the mines in the region had been abandoned. This was likely due to the exhaustion of easily accessible ores and the increasing depth of workings leading to drainage issues. Climate deterioration and increased precipitation might have contributed to this as well.

Mining Continuation: Some mines, such as Great Orme in Wales, continued to be exploited into the Middle Bronze Age (c.1500-1400 BC) and even into the Late Bronze Age and Iron Age. This indicates a long history of copper mining in certain regions.

Absence of Smelting Sites: Despite evidence of mining activity, no clear evidence of smelting sites associated with Early Bronze Age and Middle Bronze Age mines have been found. The absence of smelting evidence poses questions about the nature of metal production in these regions.

Importance and Future Research: The research on prehistoric copper mining in Britain is essential. Future research should address questions about the production figures of copper from these mines, the amount of recycling and metal import, and the presence of undiscovered sites

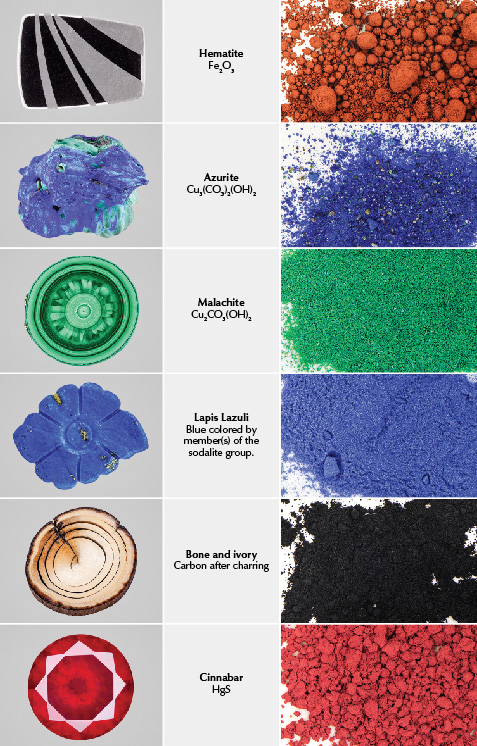

1. Pigments

Mineral pigments are naturally occurring coloured substances derived from minerals and rocks. These pigments were used by prehistoric societies for various purposes, including cave painting, body adornment, and the creation of art and artefacts. Here’s more information about mineral pigments and their use in prehistoric times.

Types of mineral pigments: Mineral pigments come in various colours, each originating from different minerals. Some common examples include:

Red and yellow ochre: Derived from iron oxides and clay minerals.

Black charcoal: Made from charred wood or other organic materials.

White chalk: Composed of calcium carbonate or calcium sulfate.

Green malachite: A copper carbonate mineral with a vibrant green colour.

Blue azurite: A copper carbonate mineral with a deep blue hue.

Brown and black manganese dioxide: Used for darker shades.

Sources: Prehistoric people sourced mineral pigments from local geological deposits. They often grind or crush the minerals to create fine powders that could be mixed with water, animal fat, plant sap, or other binders to make paint or pigment mixtures.

Cave paintings: One of the most famous uses of mineral pigments in prehistoric times is for cave paintings. Ancient humans, such as those from the Paleolithic and Neolithic periods, painted intricate and vivid images on cave walls using mineral pigments. The exact purposes of these paintings are not fully understood, but they likely served religious, ritualistic, or storytelling functions.

Body adornment: Prehistoric people also used mineral pigments for body painting and personal adornment. They would apply pigments to their bodies for ceremonies, rituals, tribal identification, or simply as a form of expression.

Art and artefacts: Mineral pigments were used to create various prehistoric art and artefacts, including pottery, sculptures, and tools. Dyes were often applied to these items to add colour and decoration.

Symbolism and cultural significance: The choice of colours and the use of certain mineral pigments might have held symbolic and cultural importance for prehistoric societies. For example, red ochre may have represented blood or life force, while black pigments could have been associated with death or mourning.

Preservation: Using mineral pigments in prehistoric art has allowed these ancient creations to survive for thousands of years. Many cave paintings and artefacts have been remarkably well-preserved, offering valuable insights into the lives and beliefs of prehistoric people.

Using mineral pigments in prehistoric times showcases the early humans’ creativity and resourcefulness in harnessing the natural world to express themselves artistically and communicate their ideas and beliefs across generations.

Overall, the archaeological investigations into prehistoric copper mining in Britain provide valuable insights into the metal production processes and economic and environmental factors that influenced mining activities during that period.

Prehistoric Times

Alderley Edge, located in Cheshire, England, has been hypothesised to have been a site of prehistoric extraction of mineral pigments, including malachite, azurite, manganese wad, iron oxide, and pyromorphite. The extraction may have occurred during the Mesolithic to Early Bronze Age, but no clear archaeological evidence exists to confirm this. The suggested locations for this activity are the soft Bunter (Upper Mottled Sandstone) at Pillar Mine and the interbedded mudstone horizons containing azurite nodules at Devil’s Grave and Engine Vein. The presence of Mesolithic flint scatters on the edge, possibly indicating occupation sites, is coincidental with the mineral outcrops.

In the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire, there is potential early evidence for iron ochre pigment extraction. Rare small hand-held cobblestone implements used as crushing stones, presumably for hematite, have been found within old ironstone mines, such as Clearwell Caves, which likely have medieval or even pre-medieval origins. Hammerstones recovered from old scowls in a quarry at Drybrook on the east side of the Severn also show evidence of grooving for hafting and crushing stones. Nearby cup-marked hollows in bedrock have been interpreted as anvils or mortars for crushing hematite. While no specific date has been ascribed to these workings, it has been suggested that they could be Bronze Age in origin.

In Exmoor, specifically at Roman Lode near Simonsbath, evidence of Early Bronze Age activity has been found, including a large hearth and a deposit containing anthropogenically smashed quartz. This location is associated with the surface outcrop of a hematite lode exploited historically for iron. Although the excavators considered the possibility of copper exploration, hematite ochre pigment exploration is also a plausible explanation for this evidence.

In Cumbria, two polished stone celts were discovered in old hematite workings at Stainton, Barrow-in-Furness, during the 1870s. The significance of this finding is unclear, but it raises the question of whether it could be evidence of associated mining, possibly for pigment.

Roman Period

Pot Shaft at Engine Vein in Alderley Edge might have been worked for a blue pigment made from azurite nodules found in a mudstone horizon within the Engine Vein Conglomerate. Malachite and azurite disseminated within the softer underlying Bunter sandstones could have been extracted for pigments. A similar Roman mine in Germany, Wallerfangen-Saar, was worked for azurite pigment (Egyptian Blue) during the 2nd-4th centuries AD, using a parallel shaft and level construction method. However, the connection between Pot Shaft and pigment extraction is speculative, and more research is needed to confirm this possibility.

2. Copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu and atomic number 29. It is a ductile metal with excellent thermal and electrical conductivity. Copper is found naturally in the Earth’s crust and has been used by humans for thousands of years due to its beneficial properties.

In prehistoric times, copper played a crucial role in the development of human civilisations. Here are some ways copper was used during that era:

Tools and weapons: Prehistoric people discovered that copper could be easily shaped into tools and weapons through hammering and casting. Copper tools were used for cutting, digging, and shaping materials. Additionally, early humans used copper to create simple weapons such as knives, spearheads, and arrowheads.

Ornaments and jewellery: Copper’s attractive reddish-brown colour made it a desirable material for decorative items. Prehistoric societies used copper to create decorations and jewellery, often associated with status, wealth, and social significance.

Containers and vessels: Copper’s malleability allowed prehistoric people to create containers and receptacles for storing food, liquids, and other materials. Early copper vessels helped in food preparation, storage, and transportation.

Ritual and ceremonial objects: In prehistoric societies, copper artefacts held cultural and ritual significance. They were used in religious ceremonies, burial practices, and other important rituals.

Currency and trade: As civilisations developed, copper became one of the earliest forms of money and played a role in trade and economic systems. It was used as copper ingots or shaped into standardised forms for exchange.

Metalworking advancement: The use of copper marked an essential step in developing metalworking skills. It laid the foundation for the discovery and use of other metals like bronze, an alloy of copper and tin that played a significant role in the Bronze Age.

It is essential to note that the prehistoric use of copper predated the development of smelting techniques that extract copper from its ores. Early humans often found native copper, which is copper in its pure metallic form, in various places, making it relatively easy to work with compared to copper ores.

The knowledge and utilisation of copper significantly impacted prehistoric cultures, allowing for technological advancements, improved living conditions, and the rise of more complex societies. Copper’s role in shaping prehistoric civilisations eventually led to the transition from the Stone Age to the Copper Age and beyond, influencing the trajectory of human history.

Prehistoric Times

The Southwest (Cornubian) orefield of Cornwall and Devon, known for its rich mining history, has not provided conclusive evidence for prehistoric hard-rock metal mining or copper extraction during the Bronze Age. Circumstantial evidence of stone mining tools can be found in some collections, but it is challenging to distinguish them from tools used for later tin ore crushing. However, a significant find was the analysis of Early Bronze Age copper artefacts that suggested a source within an ore body associated with the Cornubian granite batholith, possibly the St. Austell intrusion. While local copper-alloy metalworking has been identified at Middle Bronze Age settlements, there is no evidence of primary smelting in the region.

The Isle of Man has yielded evidence of prehistoric prospection for copper. Hammerstones associated with copper mineralisation were found on the Langness peninsula and other locations around the island’s southern tip. Additionally, Copper Age/Early Bronze Age metalwork from the Isle of Man shows affinities with Irish, early Welsh, and Scottish axes, indicating connections with metalworking in neighbouring regions.

Alderley Edge has provided evidence of Early Bronze Age copper mining. Fieldwork and excavation have revealed a prehistoric mining landscape dating back to approximately 1888-1677 cal BC. Stone tools and artefacts, including an oak shovel and hammerstones, were discovered in the area. Reconstructions of primitive smelting operations were undertaken at Alderley Edge, suggesting the possibility of local smelting during the Early Bronze Age.

The Ecton Copper Mine in Staffordshire has provided evidence of Early Bronze Age copper mining. Surface excavations and underground exploration revealed stone hammers, bone tools, and antler picks dating back to approximately 1880–1680 cal BC. The evidence suggests the existence of a second locality for Bronze Age copper mining in England.

Llanymynech Ogof, located on the border between England (Shropshire) and Wales, is a labyrinthine system of mine passages. Although initially thought to be a Roman mine due to the discovery of Roman coins and a coin hoard, it is now believed to be of Iron Age or earlier. Antler pick tools, a round hammerstone, and evidence of mining or smelting-related copper pollution have been found underground. Excavations at a nearby site, Downgay Lane, uncovered a Middle Iron Age copper smelting site with furnaces and evidence of copperworking dating back to approximately 275–10 BC.

Overall, while some regions in the British Isles have yielded evidence of prehistoric copper mining and metalworking, the evidence is limited, and more research is needed to fully understand the extent and nature of prehistoric copper extraction and metalworking practices in the region.

Roman Period

The discovery and excavation of Pot Shaft primarily represent the Roman presence at Alderley Edge. This site is a 12-meter-deep abandoned Roman shaft and cross-cut level found in March 1995. The excavation, undertaken in October 1997, revealed a 2m x 2m square shaft that connected to the open stope of Engine Vein. The style of coarse pick-work on the walls of Pot Shaft is reminiscent of Roman workings witnessed in other mining sites, such as the Dolaucothi gold mine in South Wales.

While the age of the in situ timbers found within the base of Pot Shaft does not definitively rule out a pre-Roman Iron Age date, the mining style suggests an early Roman period. Radiocarbon dating of the basal sawn oak timber produced a date range that could correspond to the Early Roman period (mid-1st century AD).

The extent of Roman mining activity at Alderley Edge seems relatively limited. There is no evidence of adit levels or extensive surface spreads of Roman mine spoil. The absence of Roman pottery or other artefacts also suggests that the Roman activity at Engine Vein was likely short-lived, possibly lasting over 20 years.

Pot Shaft’s mining use could have been under military control, potentially involving the XX Legion based in Chester. However, the evidence points to a small-scale operation, likely aimed at sampling the unexploited vein lying beneath the earlier Bronze Age workings.

Pot Shaft is the most complete and archaeologically excavated Roman mining feature in England found at Alderley Edge. The Roman activity at the site appears to have been limited and relatively short-lived, primarily focused on the exploration and potential extraction of minerals from Engine Vein.

3. Tin

Tin is a chemical element with the symbol Sn and atomic number 50. It is a silvery-white metal known for its low toxicity and ability to resist corrosion. Humans have used tin since ancient times, and its use played a crucial role in developing prehistoric societies. Here’s how tin was used in prehistoric times:

Alloying with copper to create bronze: One of the most significant uses of tin in prehistoric times was its alloying with copper to produce bronze. Bronze is an alloy composed mainly of copper, tin, and sometimes other metals like zinc. Adding tin to copper resulted in a more robust and durable metal than copper or tin alone. This marked a significant technological advancement, leading to the Bronze Age and revolutionising various aspects of prehistoric cultures.

Bronze tools and weapons: The development of bronze allowed prehistoric societies to produce superior tools and weapons. Bronze tools, such as axes, adzes, chisels, and knives, were widely used for agriculture, construction, and craftsmanship. Bronze weapons, including swords, spears, and arrowheads, provided military advantages and influenced the nature of warfare.

Ornaments and decorative items: Tin, like copper, was also used to create ornaments, jewellery, and decorative items. Bronze artefacts were often associated with status, wealth, and social significance, and they were used for personal adornment and in religious and ceremonial contexts.

Containers and vessels: Bronze’s durability and resistance to corrosion made it suitable for crafting containers and receptacles for storing liquids and other materials. Bronze vessels were used for various purposes, including food storage, cooking, and ceremonial offerings.

Coins and currency: With the discovery of bronze, societies began using metal objects as a form of currency and a means of exchange in trade. Early bronze objects, such as small ingots or standardised shapes, were used as early forms of money.

Art and sculpture: Bronze became a favoured material for creating art and sculptures during prehistoric times. Skilled artisans crafted bronze statues and figurines that depicted gods, heroes, animals, and other significant subjects.

The widespread use of bronze in prehistoric times marked a significant advancement in metallurgy and profoundly impacted the development of human civilisations. The Bronze Age, characterised by the general use of bronze tools and artefacts, laid the foundation for more complex societies and increased trade and cultural exchange.

It’s important to note that while the exact timeline of the Bronze Age varied across different regions, its emergence generally marked a period of significant progress and cultural transformation in prehistoric societies.

Prehistoric Times

During the Bronze Age, it is highly probable that alluvial tin (cassiterite) was exploited from tin-rich areas in Cornwall and Devon. Although the evidence of local extraction in the Early Bronze Age is limited, some findings indicate tin smelting activities. For example, seven fragments of tin slag were found associated with a dagger within the basal layer of turves of the Caerloggas I barrow at St. Austell, representing inefficient smelting of local tin carried out around the 16th century BC. Additionally, cassiterite pebbles were discovered at the Bronze Age settlement of Trevisker.

Penhallurick (1986) suggests that over 40 prehistoric artefacts recovered from later tin streaming activities could be objects left by Bronze Age tinners, as the same tin gravels were likely to have been worked again. Some tin streams around the margins of the source granites, particularly those around St. Austell, are considered to have been worked in prehistory.

The exploitation of tin in the Southwest and its trade with the Continent likely started in the Late Iron Age and possibly earlier. Classical sources refer to the Cassiterides (islands) and to Ictis, which is believed to be a trading site associated with tin. It is suggested that such tin exploitation and trade dates back at least to the Late Bronze Age, considering the presence of trading sites around the coast.

Excavations at Chun Castle revealed evidence of tin smelting in the pre-Roman Iron Age (3rd-2nd century BC), indicating local exploitation of tin. Similar sites showing evidence of tin smelting and likely tin exploitation during the Iron Age include Trevelgue and the Iron Age settlement of St. Eval.

Roman Period

Tin exploitation from placer deposits continued during the Roman period. Ingots of tin recovered from Cornish sites, such as Trethurgy, which were stamped with helmeted heads, suggest Roman involvement in tin trade. The recovery of plano-convex tin ingots from Bigbury Bay in South Devon dating from the Late Roman period (4th-5th century AD) further supports the continuation of tin trade during this era.

Roman artefacts associated with tin workings have been found at sites like Pentewan in St. Austell and Treloy in St. Columb Minor. However, due to intense and focused placer tin exploitation in recent centuries, physical remains of prehistoric or Roman tin workings of this type are unlikely to have survived. Recent examination of Devon’s river sediments away from the moorland has provided radiocarbon dates suggesting that wastes from tin working processes on Dartmoor were deposited in the rivers during the Roman and post-Roman periods.

4. Gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au and atomic number 79. It is a dense, soft, yellow metal known for its beauty, rarity, and resistance to corrosion. Humans have treasured gold for millennia and have played a significant role in shaping prehistoric societies. Here’s how gold was used in prehistoric times:

Adornment and jewellery: One of the primary uses of gold in prehistoric times was personal decoration and jewellery. Early humans discovered the allure of gold due to its natural beauty and rarity. Gold was fashioned into jewellery, such as necklaces, bracelets, rings, and earrings, to enhance personal appearance and symbolise wealth and status.

Religious and ceremonial objects: Gold’s intrinsic value and symbolic significance led to its use in religious and formal contexts. Gold artefacts were used in religious rituals, temple decorations, and as offerings to gods or deities.

Currency and trade: Gold, like other precious metals, was an early form of currency in prehistoric trade. Its value and universal acceptance made it an ideal medium of exchange for goods and services across different cultures and regions.

Status and wealth display: Owning gold in prehistoric times was a sign of wealth, power, and prestige. Gold objects were often owned by rulers, nobles, and wealthy individuals and were displayed as symbols of social standing.

Craftsmanship and art: Skilled artisans used gold to create intricate and ornate objects, including statues, figurines, and decorative items. Gold’s malleability allowed it to be shaped into detailed forms, making it a favoured material for artistic expression.

Burial practices: Gold artefacts were sometimes buried with individuals of high status or importance. Gold objects found in burial sites from prehistoric times provide valuable archaeological insights into the beliefs and practices of ancient societies.

Symbolism and religious significance: Beyond its material value, gold was symbolic in prehistoric cultures. It was associated with the sun, divinity, immortality, and the eternal nature of the gods.

It’s important to note that while gold was used in prehistoric times, its availability was limited compared to today. Early civilisations primarily sourced gold from placer deposits, riverbeds, and surface mines. As more sophisticated mining techniques were developed over time, gold became more accessible, and its use expanded.

Gold’s allure and importance have persisted throughout human history, shaping trade, economies, and cultural practices. In contemporary times, gold continues to hold a significant role as a store of value, a medium of exchange, and a symbol of wealth and luxury.

Prehistoric Times

During the Bronze Age, there was evidence of gold recovery from tin ground in Cornwall. During the historical period, Tinners regularly recovered small amounts of gold from areas such as Treloy and the Carnon Valley. While this alone is insufficient evidence to identify these sites as English Bronze Age gold sources conclusively, there is more intriguing evidence. British Bronze Age goldwork, to a significant extent, contains small quantities of tin in parts per million. However, samples of native gold from Ireland, Wales, and Scotland are either devoid or have shallow levels of tin. On the other hand, Cornish gold has been shown to contain significant amounts of tin, ranging from 25-50 ppm. Early Bronze Age gold lunulae from Harlyn Bay, Padstow, and St. Juliot have also revealed tin concentrations ranging from 50 ppm to 950 ppm.

The presence of tin in Cornish gold suggests that gold was likely produced as a byproduct of alluvial tin mining from the Bronze Age onwards, possibly in places like the Carnon Valley. Research is being conducted on the trace element composition of native gold and Bronze Age gold artefacts in Ireland to identify sources. Similar studies could be valuable in England and the rest of the UK, and analysing stable isotope ratios may also prove effective in determining the origin of alluvial gold.

Roman Period

During the Roman period, gold production in Britain was limited, but there were a few known sources of gold mining. The Romans were particularly interested in exploiting Britain’s mineral resources, including gold, for their empire.

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines, located in present-day Carmarthenshire, Wales, were one of the most significant gold-producing areas during the Roman occupation of Britain. These mines are believed to have been exploited by the Romans from around 75 AD until the end of the 3rd century AD. The Romans used advanced mining techniques, such as hushing (using water to wash away soil and expose gold-bearing rocks), open-cast mining, and deep mining to extract gold from the veins in the Welsh hills.

Clogau St David’s Mine, situated in what is now Gwynedd, Wales, was another gold mine known to have been worked during the Roman period. The Romans likely extracted gold from this mine and other nearby deposits. The Gwynfynydd Gold Mine, located near Dolgellau in Gwynedd, Wales, is known to have been a significant source of gold during the Roman period and continued to be active throughout the medieval period.

It’s worth noting that while these mines were productive during the Roman period, the overall gold production in Britain during that time was relatively modest compared to other regions in the Roman Empire, such as Spain and Dacia (modern-day Romania), where more significant and more abundant gold deposits were exploited.

The Romans used the gold from these mines for various purposes, including coinage, jewellery, religious artefacts, and offerings to temples and deities. Today, these ancient gold mines are of historical and archaeological interest, and some are open to visitors as tourist attractions.

5. Lead

Lead is a chemical element with the symbol Pb and atomic number 82. It is a heavy, bluish-grey metal known and used by humans for thousands of years. In prehistoric times, lead was used for various purposes, though its usage was not as widespread as other metals like copper, gold, and silver. Here’s how lead was used in prehistoric times:

Pigments and dyes: Prehistoric people used lead-based compounds, such as lead oxide (red lead) and lead carbonate (white lead), as pigments and dyes. These lead-based pigments were used to add colour to various materials, including cave paintings, ceramics, and textiles.

Amulets and ornaments: Lead was occasionally used to create small amulets and ornaments. Although not as common as other metals, lead artefacts have been found in prehistoric sites, suggesting their use as decorative items or talismans.

Seals and weights: In some ancient civilisations, lead was used to make seals and weights. Seals made of lead were used for stamping impressions on clay or wax, serving various administrative and commercial purposes. Lead weights were used for trade and measurement.

Water pipes: Although not as widespread in prehistoric times, some evidence suggests that ancient civilisations used lead pipes for water transportation. Lead pipes were durable and malleable, making them suitable for plumbing systems.

Glazing and pottery: Lead compounds were sometimes used in glazing pottery to achieve specific colours and effects. Lead glazes were known for their smooth finish and shiny appearance.

The health risks associated with lead exposure were not fully understood at the time, and ancient societies may have unknowingly exposed themselves to lead poisoning through the use of lead-based pigments and other lead-containing materials.

Prehistoric Times

In the Bronze Age, lead was intentionally added to tin bronze during the Acton Park (Middle Bronze Age, 1400-1300 BC) and Wilburton (Late Bronze Age, 1000-900 BC) metalworking periods in the Southwest of England. Burgess and Northover suggest that the lead was probably sourced from British locations, and stable lead isotope analysis of bronze artefacts and ores later supported the possibility of a match between Wilburton metalwork and a lead source in the Mendips, Somerset.

In the Peak District, lead use was evident during the Late Bronze Age. A socketed axe made of lead was discovered at Mam Tor, which might represent one of the earliest exploitations of lead in the region. Also, Late Bronze Age axes from Britain containing up to 15-21% lead are considered to have been sourced indigenously.

Bronze Age lead mining has also been proposed at Llanymynech on the Welsh-Shropshire border.

In the Mendips, pre-Roman (Iron Age) lead mining has been suggested at Charterhouse-on-Mendip based on finds of a 3rd-century BC Greek coin, a denarius of Julius Caesar, and Iron Age pottery from excavation trenches sampling “Roman” mining rakes on the edge of the Charterhouse Roman fortlet.

Roman Period

Lead was extensively used for various purposes, including plumbing, water management systems, coffins, lead glass, spindle weights, and alloying with tin to produce pewter. Lead compounds were also commonly used as adulterants in wine and cosmetics. Numerous Roman lead pigs have been found on routes from orefields to ports, where lead was exported to other parts of the Roman Empire.

In the Mendips, Roman mining has been confirmed at Charterhouse-on-Mendip, and other areas suggest possible Roman mining based on finds of Roman lead smelting slag and evidence of opencut mining rakes. The Matlock area is also a potential location for Roman lead mining.

There is evidence of Roman lead and silver mining at Combe Martin, Calstock, Alderley Edge, the Peak District, Shropshire, and County Durham. However, some of the evidence is circumstantial or requires further examination. The Roman economy of the South Pennines, with a focus on the lead industry, has been thoroughly explored by Dearne.

Cumbria claims that the second cohort of Nervians conducted mining during the 3rd century AD, and recent excavations in Carlisle revealed a lead smelting furnace probably linked to lead from the Alston orefield.

6. Silver

Silver is a chemical element with the symbol Ag and atomic number 47. It is a lustrous, white metal known for its excellent conductivity of electricity and heat. Humans have used silver for thousands of years, and its history dates back to prehistoric times. Here’s how silver was used in prehistoric times:

Adornment and jewellery: Silver was used for personal adornment and jewelry in prehistoric times, like other precious metals. Early humans fashioned silver into necklaces, bracelets, rings, and other ornaments to enhance their appearance and symbolise wealth and status.

Currency and trade: Silver was an early form of money in prehistoric trade. Its rarity, durability, and universal acceptance made it a valuable medium of exchange for goods and services across different cultures and regions. Silver objects were used for trade, gifts, and as a store of wealth.

Ritual and ceremonial objects: Silver’s intrinsic value and beauty led to its use in religious and formal contexts. Silver artefacts were used in religious ceremonies, temple decorations, and as offerings to gods or deities. The metal’s radiant appearance and association with the moon and water symbolised purity and spirituality.

Utensils and containers: Prehistoric societies used silver to create utensils, such as cups, bowls, and plates. Silver’s antimicrobial properties made it particularly suitable for storing food and liquids.

Art and craftsmanship: Skilled artisans used silver to create intricate and decorative objects, including figurines, statues, and other works of art. Silver’s malleability and ability to hold intricate details made it a favoured material for artistic expression.

Mirrors and reflective surfaces: In some cultures, polished silver surfaces were used as mirrors in prehistoric times. These mirrors served practical and decorative purposes.

It’s important to note that while silver was used in prehistoric times, its usage was not as widespread as other metals like copper and gold. The scarcity of silver in some regions and the difficulty in extracting and refining it limited its availability for broader use.

Silver’s value and importance have persisted throughout human history, and it continues to be treasured for its various applications in modern times. Silver is used in a wide range of industries, including electronics, photography, jewellery, and medicine, among others. It remains a valuable precious metal with a significant role in global economies and cultural practices.

Prehistoric Times

There is limited evidence of silver mining in prehistoric Britain, and it is challenging to identify specific mines that produced silver during that era. The knowledge of mining activities during prehistoric times is derived from archaeological evidence and historical accounts, but many details remain uncertain.

However, some known sources of silver deposits in Britain might have been exploited to a limited extent during prehistoric times, such as the Cumbrian region, particularly around the Lake District, which is known for its lead and zinc deposits, and silver can be found alongside these metals. It is possible that silver was extracted incidentally during the mining of lead and zinc ores in the area.

Mynydd Parys (Anglesey, Wales) or Parys Mountain, is known for its rich deposits of copper ore. While copper was the primary metal of interest, small amounts of silver could have been extracted alongside the copper during prehistoric mining.

The region around Cornwall and Devon in southwestern England is known for its mining heritage, including the extraction of tin and other metals. Although no major silver mines are known in the area, silver could have been found as a byproduct of tin mining.

It’s important to note that prehistoric mining techniques were relatively rudimentary compared to later periods, and the scale of mining operations was likely small. The exact extent of silver mining in prehistoric Britain remains unclear, and much of the evidence has been eroded or obscured over time.

Prehistoric societies might have been aware of the presence of silver, but their focus on mining and metalworking was generally centred on other metals like copper, tin, and lead. Silver’s value and significance in prehistoric times were likely less pronounced than in later historical periods.

The only excavations undertaken on the Mendips (by Todd at Charterhouse) suggest the possible survival of in situ mining features and likely smelting hearths dating from the early Roman period.

Also, possible pre-Roman remains dating from the 1st millennium BC. Potentially one of the most important early Roman lead mining areas within Britain, this area is worthy of a detailed survey, soil

augering, geophysics and a better-planned and larger-scale excavation. Given the silver content of these ores, the Mendip is also an area to look for evidence of silver extraction (cupellation) from these ores (see Ashworth 1970, 15).

Roman Period

During the Roman period, silver production in Britain was limited, but there were some known sources of silver mining. The Romans wanted to exploit Britain’s mineral resources, including silver, for their empire.

Mendip Hills (Southwest England): The Mendip Hills in Southwest England, particularly around the modern-day county of Somerset, were known to be a significant source of lead and silver during the Roman occupation. Lead mining was the primary focus, but silver was often found alongside lead deposits. The Rio Tinto Mine, located in what is now Cumbria in North-west England, was another source of lead and silver during the Roman period. The mine is one of the oldest known metal mines in the world and has a long history of exploitation, including during the Roman occupation.

Mynydd Parys (Anglesey, Wales), also known as Parys Mountain, located on the Isle of Anglesey in Wales, was a significant source of copper mining during the Roman period. While copper was the primary metal of interest, some silver was also extracted alongside the copper ore.

It’s important to note that the Roman period in Britain spanned from around 43 AD to 410 AD. During this time, the extraction and production of silver were not as extensive in Britain compared to other regions in the Roman Empire, such as Spain and parts of Germany, where more significant and abundant silver deposits were exploited.

The Romans used the silver extracted from these mines for various purposes, including coinage, jewellery, religious artefacts, and offerings to temples and deities. Today, these ancient mines are of historical and archaeological interest, and some are open to visitors as tourist attractions.

7. Zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. It is a bluish-white metal that is relatively rare in its pure form. In prehistoric times, zinc was not commonly used or recognised as a distinct metal due to its scarcity and difficulty extracting it from its ores. Instead, prehistoric societies would have encountered zinc in its natural form, primarily as a component of certain minerals and ores.

Zinc is found in the Earth’s crust, usually in zinc sulfide (sphalerite) or zinc carbonate (smithsonite). These zinc-containing minerals were present in some geological formations and might have been visible on the surface or in shallow deposits, where prehistoric people could have encountered them.

While zinc was not used as a primary metal in prehistoric times, it might have been incidentally encountered and used in small quantities as an alloying element. For example, zinc is known to occur naturally alongside copper ores, and some ancient copper artefacts have been found to contain trace amounts of zinc.

Prehistoric societies might have observed that certain zinc-containing minerals had medicinal properties, as zinc is essential for human health. However, the use of zinc-based minerals for medicinal purposes would have been based on empirical observations rather than a scientific understanding of the metal’s properties.

Overall, the knowledge and use of zinc in prehistoric times were likely minimal compared to other more accessible metals like copper, gold, and silver. Only in later historical periods did zinc become recognised as a separate metal and used more extensively in various applications.

It wasn’t until much later in history, around the 13th century, that zinc was recognised as a distinct metal and utilised in various applications. In the modern era, zinc has become an essential metal used in numerous industries, including construction, transportation, and electrical engineering, and as a crucial component in producing brass and other alloys.

Prehistoric Times

There was no direct evidence of Prehistoric mining in the Mendips or other areas in the UK. However, given the known mining of lead from these regions, it is plausible that the Romans might have also exploited the abundant near-surface calamine ores (zinc carbonate, also known as smithsonite) to produce brass using cementation.

Brass is an alloy made primarily of copper and zinc, and during the Roman period, the cementation process was used to produce brass by heating a mixture of copper and calamine in a closed vessel. The zinc vapour produced during this process would react with the copper, forming brass. While there is no direct evidence of zinc mining in the Roman period, the presence of calamine deposits near known lead mines suggests the possibility of zinc extraction for brass production.

Roman Period

During the Roman period, zinc mining was not a significant industry in the UK. Zinc is a relatively rare metal in its pure form, and its extraction and processing were not well-developed during ancient times. However, zinc occurs naturally in combination with other metals, mainly zinc carbonate (smithsonite) and zinc sulfide (sphalerite) minerals, which may have been encountered during mining for other metals like lead.

The Roman period in the UK spanned from around 43 AD to 410 AD, and the primary focus of mining was metals like lead, silver, and copper. As a distinct metal, zinc was not well-known or widely used during this era.

In the modern era, zinc mining in the UK became more prominent during the 18th and 19th centuries, especially in the Yorkshire Dales region is known for its lead mining, and zinc ore was often found alongside lead deposits. The North Pennines region, including areas like Alston Moor in Cumbria, was a significant mining area for lead, and zinc was seen as a byproduct of lead mining.

It’s essential to understand that ancient mining activities, including those during the Roman period, were often on a smaller scale compared to later historical periods. The full extent of mining for specific metals in Roman Britain remains a subject of ongoing archaeological research and investigation, so this may change as more excavations are undertaken.

8. Iron

Iron is a chemical element with the symbol Fe and atomic number 26. It is a metal that is abundant in the Earth’s crust and is the most widely used metal in the world. Humans have used iron for thousands of years, and its history dates back to prehistoric times. Here’s how iron was used in prehistoric times:

Tools and weapons: One of the most significant uses of iron in prehistoric times was to produce tools and weapons. Early humans discovered that iron could be heated and shaped into implements, including axes, knives, spears, and other cutting and piercing tools. Iron tools were more durable and efficient than those made from earlier materials like stone or copper, leading to significant technological advancements.

Agriculture: Iron tools revolutionised agriculture during prehistoric times. Iron ploughs, hoes, and other implements made tilling the soil and farming more efficient, increasing food production and developing settled agricultural communities.

Artefacts and ornaments: Iron was occasionally used for crafting decorative items and decorations during prehistoric times. While not as common as copper or gold, iron artefacts have been found in prehistoric archaeological sites, suggesting their use for artistic and symbolic purposes.

Building materials: Prehistoric societies used iron in construction and building projects. Iron nails, hinges, and other fasteners were employed to join wooden structures and create more durable and stable buildings.

Trade and commerce: Iron ingots and bars were sometimes used as currency or as trade items in prehistoric societies. As ironworking techniques spread, iron objects became valuable commodities for exchange.

It’s important to note that the widespread use of iron in prehistoric times marked a significant transition from the Stone Age to the Iron Age. The Iron Age, which followed the Bronze Age, saw the increasing use of iron for tools, weapons, and various artefacts, leading to transformative changes in human societies.

Prehistoric ironworking involved smelting iron ore in furnaces, a process requiring high temperatures and skilled craftsmanship. As iron became more widely available, it played a crucial role in developing civilisations, contributing to the rise of empires and influencing the course of human history.

Prehistoric Times

In the archaeological record, evidence of iron extraction is primarily found in the remains of smelting hearths. The original ore sources are identified based on samples found near these hearths. The development of iron extraction in Britain evolved from the bowl furnace to the shaft furnace and then the slag pit furnace (Tylecote 1986).

Iron smelting found at sites distant from known iron ore sources, such as Mucking in Essex and Hevingham in Norfolk, indicates either ore movement or bog iron’s once widespread occurrence. Geological origins of iron ore in Britain are diverse, including vein hematite and goethite (found in Furness, Cumbria; Brendon Hills, Somerset; and Forest of Dean), blackband ironstones (siderite) found in coalfield areas, Wealden ironstones (siderite) from Sussex, Hampshire, and Surrey, as well as Cretaceous Greensand ores like Carstone in Bedfordshire and Upper Greensand ores in Devon.

Prehistoric Iron ore can also be found in the abundance in following counties:

Dorset: Locally collected iron ore was extracted from cliffs at Hengistbury Head and smelted between 400 BC and AD 50 (Bushe-Foxe 1915). Similar evidence of locally sourced iron ore and smelting was found in Gussage All Saints (Wainwright et al. 1979).

Wiltshire: Iron ore was smelted at All Cannings Cross, Wiltshire, between 400-250 BC, using ore from the local Lower Greensand, likely from Seend (Cunnington 1923).

Somerset: A short rake (opencut) at Charterhouse-on-Mendip, examined by Todd in 1996, contained hematite ore rather than lead. Denarii of Julius Caesar (48 BC) and some Iron Age pottery were recovered. Other potential Iron Age mineworkings are poorly explored and often undated, including sites at Kitnor Heath on Exmoor and Colton Pits in the Brendon Hills (L Bray pers comm).

Devon: An Early Iron Age smelting site at Kestor near Chagford in Devon, dated just after 400 BC, may have reduced a local bog iron ore (Tylecote 1986). There is some debate about the date of the site, and additional C14 dating indicates it may be from the 6th century AD. The slag at Kestor is believed to be associated with trial working of ores that didn’t succeed rather than regular production (Peter Crew’s observations).

Cornwall: One of Cornwall’s earliest iron extraction sites is the promontory fort of Trevelgue Head. Between the Mid and Late Iron Age, approximately 1.5 to 2.3 tonnes of iron were produced from a narrow lode running through the headland (see Dungworth in Nowakowski 2011). The scale of Iron Age extraction here was limited, making between 10 and 20 kg of iron per year, suggesting short-lived and localised exploitation.

Surrey: At Brooklands near Weybridge, slag weighing up to 44 kg was found as part of the waste from slag-tapping furnaces operated between the Early and Late Iron Age (from the 5th century BC to 1st century AD). The ore source was likely high-quality sideritic ironstone from nearby St. George’s Hill. At Purberry Shot near Ewell, furnace bases and a bloom dating from 200 BC – AD 150 represent a small industry using local iron ores from the Wadhurst Clay (Lowther 1946).

Sussex: Pre-Roman iron smelting (190-80 BC) in shaft furnaces with slag-tapping pits has been identified at Broadfield near Crawley in Sussex, using local Wealden iron ores (siderite). Other Wealden Roman furnaces have been found in the area, such as at Crowhurst Park, Bardown, and Chitcomb (Tylecote 1986).

East Anglia: Iron smelting and ironworking have been found at recently excavated fenland edge Iron Age settlements, like Bradley Fen, Cambridgeshire, possibly exploiting local bog iron ores or Northamptonshire ironstone (Fincham 2004).

Northamptonshire: The settlement at Hunsbury contained pits with significant amounts of iron slag, suggesting smelting operations using local Northamptonshire ironstone. Other Iron Age furnaces have been found at Wakerley (Tylecote 1986). At Priors Hall, Corby, excavations in 2006 revealed seven slag-tapping furnaces dating to the Late Iron Age, along with pottery and tuyere fragments. The local Northamptonshire ironstone was likely smelted, sourced from the area of Rockingham Forest.

East Yorkshire: The Middle Iron Age ‘Arras Culture’ around 300 BC, linked to important chariot burials and the Hasholme log boat excavation, was associated with one of Britain’s most significant prehistoric iron industries. The iron industry appears to be based on extensive deposits of bog iron ore within the coastal Foulness Valley south of Holme, Humberside. Furnaces and significant iron slag quantities from the smelting of sandy bog iron ores have been excavated at Whelham Bridge, Yorkshire (Halkon & Millet 1999).

Northern England: Early Iron Age furnaces (7th-6th century BC) have been found at West Brandon in Durham and at Roxby in Cleveland, exploiting the local Cleveland iron ore.

Roman Period

Iron can also be seen to be mined during the Roman period in the following counties:

Cornwall: Restormel Roman Fort is close to a critical iron vein called the Restormel iron lode.

Devon: Early iron extraction pits can be seen in the Blackdown Hills, with some smelting sites identified from both the Saxon and Roman periods. Pottery dating from the second half of the 1st century AD suggests Roman military control or supervision of iron exploitation, possibly centred on the legionary fortress at Exeter (Griffith & Weddell 1996). Roman-era iron ore similar to that from the Blackdowns was discovered during the excavation of the Roman fort at Bolham, Devon (Maxfield 1991).

Exmoor: Iron production increased from the beginning of the 2nd century AD, reaching substantial levels in sites on the southern fringes of Exmoor, such as Sherracombe Ford and Brayford. More recently, a Late Roman smelting site has been identified at Blacklake Wood as part of the Exmoor Iron Project (ExFe) led by Gill Juleff at the University of Exeter. The source of much of the Roman iron smelting in this area is believed to be ‘Roman Lode’ at Burcombe near Simonsbath, which was an anciently worked lode of goethite (Fletcher et al. 1997).

Somerset: Evidence of Roman iron ore extraction at outcrop has been found at Treborough and Luxborough. Roman exploitation of the hematite ores of the Brendon Hills has been suggested at Colton Pits, although no datable evidence is available (L Bray pers comm). Samian pottery scatters have been found near bloomery slag heaps at Clatworthy Reservoir.

Gloucestershire: At Lydney, a minor underground working of iron ore (goethite) was discovered, working a band of ferruginous marl, and later sealed by a 3rd-century AD hut (Scott-Garrett 1959).

Forest of Dean: Scowles, ancient open-cast iron ore workings, are relatively common in the Forest of Dean. Some of these are likely Romano-British in origin, as indicated by finds of pottery and coins. Puzzle Wood near Coleford is considered one such Romano-British scowle working (Blick 1991).

Northamptonshire: Large numbers of smithing furnaces were found at Corstopitum (Roman Corbridge), but little evidence of smelting in the form of slag suggests that the Roman military might have relied on British smelters. However, evidence of domestic iron smelting within this iron-producing region, particularly in 2nd–3rd-century villas such as Great Weldon, has been found (British Archaeology Feb 2008). The Northamptonshire ironstone was worked from shallow surface outcrops using open-cast. Traces of these workings within the Northamptonshire orefield have been found at Oundle and Laxton (Taylor and Collingwood 1926).

Lincolnshire: Roman iron smelting remains have been found at Pickworth, Bagmoor, Costerworth, and Thealby. The smelting locations lie within the area of iron mining and outcrops of the Northants ironstone (Cooper-Key 1896).

Norfolk: Extraction pits at Ashwicken obtained nodular iron ore from the Lower Greensand (carstone) horizon, likely using locally constructed tree-trunk pattern-moulded furnaces for immediate local smelting. The North Norfolk site at Hevingham also suggests local smelting, with large slag cakes in the area.

Sussex: Wealden iron ore (nodular siderite and occasionally limonite) was extracted using pits, with Roman furnaces charged with a mixture of siderite and oak charcoal. The Wealden iron ore source was typically the Wadhurst Clay exposed within the immediate vicinity. Other Wealden Roman furnaces were found at Cow Park and Pippingford, Hartfield, as well as at Holbeanwood and Broadfield near Crawley (Cleere 1970 and Tebbut and Cleere 1973). The Wealden Roman iron production has been reviewed by Hodgkinson (1999).

Northern England: Both ore and slag are associated with smelting remains at the Roman fort of Templebrough near Rotherham, Yorkshire, while the fort of Galava at Ambleside produced evidence of the smelting of local bog iron ores (Tylecote 1986).

9. Coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock composed chiefly of carbon and other elements such as hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen. It forms from the remains of ancient plants that accumulated and were subjected to heat and pressure over millions of years. Coal is primarily used as a fuel source for generating heat and electricity in modern times. However, its use in prehistoric times was more limited due to the lack of advanced mining and extraction techniques.

During prehistoric times, humans were likely aware of the existence of coal in certain regions, particularly in areas where it was exposed on or near the surface. Some of the ways coal might have been used in prehistoric times include:

Surface Fires: In regions where coal deposits were exposed on the surface, prehistoric people might have used them as a fuel source for fires. Burning coal could provide heat and light, which would have been valuable for cooking, providing warmth, and driving away predators.

Artefacts and Ornaments: Prehistoric societies might have used coal to craft particular objects or ornaments. Coal’s dark colour and relatively soft texture make it suitable for artistic expression, and there is evidence of ancient coal artefacts, such as beads and carvings, in some archaeological sites.

Medicinal Uses: Some prehistoric cultures might have used coal for medicinal purposes. It was believed to have specific healing properties and might have been used as a remedy for various ailments.

The widespread use of coal as a major fuel source only began in the industrial era, starting in the 18th century, with the advent of coal mining and advancements in technology to extract and utilise coal on a large scale.

Prehistoric Times

Evidence for the early use of coal as fuel in iron smithing operations in Britain comes from the palisaded site of Huckhoe in Northumberland (Smith 1905). A large quantity of coal and a piece of part-welded iron were found within the hearth. The origin of the coal is uncertain, although local surface outcrops were likely nearby. This early example of coal usage in ironworking appears unique to prehistoric Britain.

Roman Period

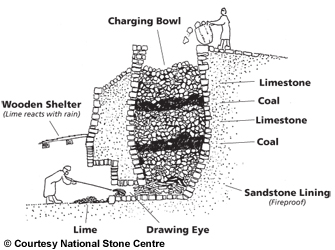

There is evidence of coal usage in Roman Britain for domestic heating and possibly iron smithing, particularly in the northern forts on the Antonine and Hadrian’s Walls. Coal usage is reported in archaeological literature at Housesteads and Corbridge forts, as well as at Chester and Manchester (Preece & Ellis 1981). Contemporary records also mention using coal to maintain the perpetual fire at the Temple of Minerva in Bath (Aquae Sulis). It seems there were three main clusters of coal use in Roman Britain. One group was centred around the Flint-Chester area, possibly sourced from the North Wales coalfield. Another collection extended from the Bristol Channel area southeastward to Silbury Hill, with a source in the South Wales and Bristol and Somerset coalfields. The final cluster was found between Cambridge and the Wash in East Anglia.

Interestingly, these sites were located considerably from the nearest coalfield sources, approximately 200 miles by sea and 40 miles by land. Coal may have been transported by sea from Yorkshire or Northumberland, similar to the way sea coal was extracted and brought to Cambridge and other East Anglian towns (Preece & Ellis 1981). The distribution of sites might relate to their proximity to the Roman Car Dyke.

Small quantities of coal were also found at Roman Wroxeter and Meole Brace in Shropshire, although it is unclear whether the coal was sourced from what would become the Shrewsbury coalfields or the Coalbrookdale area. Coal was later mined in each case in the vicinity (Ellis 2000; Evans 1999).

Recent studies, led by Travis, have provided persuasive arguments for widespread coal usage in Roman Britain based on secondary finds and coal residues retrieved from various non-mining sites, confirming extensive coal usage. Some coal samples taken from Roman contexts have been traced back to specific seams. However, despite the evidence of extensive coal usage, the exact locations of Roman coal mines remain elusive (Travis 2008).

One putative Roman coal extraction site listed in the EH Coal Industry MPP Assessment is Stratton Common near Stratton on the Fosse, Ashwick (Avon). Anciently worked coal outcrops in this area provided the nearest source of coal to Roman Bath on the Roman road network. Although documented mining began at this site in 1300 AD, it is believed to have much earlier origins (Down & Warrington 1971, 224-6).

10. Oil Shale

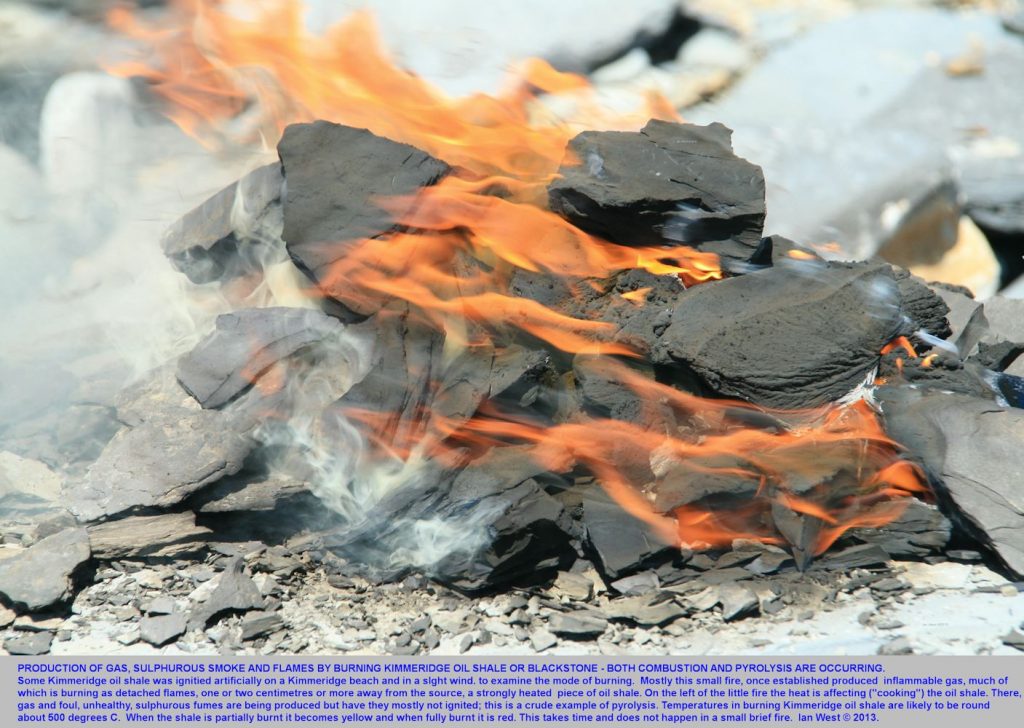

Since ancient times, humans have been utilising oil shale as a readily combustible fuel source, not requiring extensive processing. Additionally, it served decorative and construction purposes. During the Iron Age, Britons would fashion and polish oil shale into ornaments. Going back to around 3000 BC, Mesopotamians employed “rock oil” from oil shale for road construction and creating architectural adhesives.

Moreover, oil shale found application in the medical and military realms. Mesopotamians utilised it for medicinal purposes and ship caulking, while Mongols coated their arrows with flaming oil shale for military purposes. Oil shale is a sedimentary rock containing organic matter called kerogen. Kerogen is a precursor to oil and gas and can be converted into liquid hydrocarbons through pyrolysis, which involves heating the rock to high temperatures.

Prehistoric Times

Evidence suggests that prehistoric people were aware of oil shale and its properties. In some archaeological sites, there have been findings of oil shale artefacts, indicating that prehistoric humans may have used oil shale for specific purposes other than fuel.

One notable example is the use of oil shale in Iron Age salt production at Kimmeridge in Dorset, England. Archaeological evidence has shown that the Kimmeridge Shale, an oil shale found in the area, was used as a fuel source to heat ceramic vessels known as briquetage pans. These pans were used to boil and evaporate brine to extract salt. The oil shale’s combustible properties allowed the salt-makers to achieve the high temperatures needed for the brine evaporation process.

While the use of oil shale in prehistoric times was limited compared to other energy sources, such as wood and animal dung, the evidence of its utilisation in specific contexts sheds light on the resourcefulness and adaptability of ancient societies in utilising the materials available to them for various technological purposes.

Roman Period

Some evidence suggests that the Romans were aware of oil shale and its properties. They might have used it for specific purposes other than fuel. For example, there have been findings of oil shale artefacts in archaeological sites from the Roman period, indicating its presence and potential use.

The exact extent of oil shale utilisation during the Roman period is not well-documented, and its applications were likely limited compared to other available energy sources and materials. The widespread use of oil shale as a fuel source came much later in history, with technological advancements enabling efficient extraction and processing techniques.

11. Peat

Peat is a type of organic material formed from the partial decomposition of plant matter in waterlogged conditions. It is typically found in wetlands or peatlands and consists of partially decayed mosses, grasses, and other vegetation remains. Peat is rich in carbon and retains a high water content, making it a vital carbon sink and a valuable fuel source.

In prehistoric times, peat was used by ancient societies as a readily available and easily accessible source of fuel for various purposes. Some of the common uses of peat in prehistoric times include:

Heating and Cooking: Prehistoric people would collect dried peat from the surface of peat bogs or wetlands and use it for heating and cooking. They would burn peat in open fires or simple hearths for warmth and cooking food.

Lighting: Peat was also utilised as a source of light. It would be dried and used as fuel for torches, providing illumination during the night.

Preservation: Peat bogs have unique properties that facilitate the preservation of organic materials. Archaeological finds such as ancient tools, weapons, and human bodies have been exceptionally well-preserved in peat bogs, giving us valuable insights into prehistoric cultures.

Construction: In some regions, peat was used as a construction material. It was dried and used as a form of insulation or as a component of building materials for simple structures.

Prehistoric Times

Prehistoric Britain has several peat sites that have been of archaeological interest due to their preservation of organic materials and insights into prehistoric cultures. Some notable peat sites in prehistoric Britain include the Somerset Levels in southwest England have extensive peat bogs that have yielded significant archaeological finds. One of the most famous discoveries was the Sweet Track, a prehistoric wooden trackway dating back to around 3800 BC, which was found preserved in the peat.

Flag Fen, located near Peterborough in eastern England, Flag Fen is an archaeological site with well-preserved prehistoric wooden structures and artefacts preserved in the peat. Shapwick Heath, part of the Avalon Marshes in Somerset, is another critical peat site that has yielded evidence of prehistoric occupation and activity.

Fiskerton in Lincolnshire is known for its waterlogged deposits that have preserved wooden structures and artefacts dating back to the Bronze Age. Star Carr, located in North Yorkshire, is an important Mesolithic site with evidence of hunter-gatherer activity and well-preserved organic remains, including wooden artefacts and bone tools.

Mount Sandel in Northern Ireland is one of the earliest known settlements in Ireland, dating back to the Mesolithic period. The site’s waterlogged conditions have preserved critical archaeological remains.

These peat sites have provided valuable insights into prehistoric life in Britain, as the waterlogged conditions of peat bogs have preserved organic materials that would otherwise have decayed over time. Archaeological excavations at these sites have revealed ancient structures, artefacts, tools, and even well-preserved human remains, offering a glimpse into the region’s daily lives, practices, and technologies of prehistoric communities.

Roman Period

In Roman Britain, several peat sites have been discovered, although they might not be as well-known as the prehistoric peat sites. Peatlands and wetlands were widespread in Roman Britain, and some of the peat sites that have yielded archaeological evidence from the Roman period include:

Glastonbury Lake Village was a prehistoric settlement on a wooden platform in a lake. While the site primarily dates to the Iron Age, there is evidence of Roman influence and occupation, making it relevant to Roman Britain. The wetland conditions of the site have preserved organic remains, including wooden structures and artefacts.

Though primarily a Bronze Age site, Must Farm in Cambridgeshire, England, also has evidence of Roman activity. The site is a well-preserved settlement built on stilts over a river channel and has yielded a wealth of artefacts, including Roman pottery and metal objects.

Located on the Isle of Wight, Brading Roman Villa is a well-preserved Roman villa complex with evidence of occupation from the 1st to the 4th centuries AD. The site includes a hypocaust (underfloor heating system) and Roman mosaics, which were preserved due to the waterlogged conditions of the area.

Although not a peat site, Vindolanda is an important Roman fort and settlement near Hadrian’s Wall in Northumberland, England. Excavations at Vindolanda have uncovered extensive organic materials, such as wooden writing tablets, shoes, and other artefacts, preserved in anaerobic soil conditions.

Richborough in Kent, England, was an important Roman port and fort during the Roman occupation. The site contains archaeological remains that provide insights into Roman military and trading activities.

It’s important to note that while some of these sites are situated in peatlands or areas with waterlogged conditions, not all of them are classified as peat sites in the strict sense. Nonetheless, wetlands and waterlogged environments have contributed to preserving organic materials from the Roman period in various locations across Britain.

Roman salterns (salt working sites) in Essex, Cambridgeshire, Norfolk, and Lincolnshire might have used peat to fuel boiling and evaporating brine in briquetage pans (Lane & Morris 2001).

12. Jet

Jet is a black, lustrous, and lightweight gemstone composed mainly of fossilised wood from ancient conifer trees, primarily of the species Araucariaceae. It is a form of lignite, a precursor to coal, and is formed from the remains of old trees that fell into stagnant, oxygen-deprived water and underwent a process of decomposition and fossilisation.

Jet has a long and intriguing history of use dating back to prehistoric times. During the prehistoric period, people discovered jet’s value and unique properties, leading to its utilisation for various purposes. Some ways in which jet was used during this era include:

Ornamental Use: Jet’s distinctive black colour and lustrous appearance made it a sought-after material for crafting ornaments and personal adornments. Prehistoric communities fashioned jet into beads, pendants, bracelets, and other jewellery items, which were likely worn for ceremonial, spiritual, and decorative purposes.

Symbolic and Ritual Objects: The prehistoric people recognised jet’s symbolic and spiritual significance. It is believed that jet had protective properties and was used to ward off evil spirits and negative energies. Amulets and talismans made from jet were possibly worn as protective charms.

Tools and Implements: Jet’s durability and relatively soft nature made it suitable for carving into tools and implements. Archaeological evidence suggests that prehistoric communities used jet to create cutting tools, such as knives, scrapers, and needles, which aided in various daily tasks like crafting, hunting, and preparing food.

Ritual and Burial Practices: Jet held special significance in prehistoric burial practices. It was often placed within burial sites, alongside the deceased, as a symbol of mourning and remembrance. Archaeologists have discovered jet artefacts buried with individuals in some ancient graves, suggesting its role in funerary rituals and practices related to the afterlife.

Trade and Exchange: Jet, a valuable and distinctive material, likely played a role in early trade networks. Prehistoric communities might have exchanged jet items with neighbouring groups or distant tribes, enhancing cultural interactions and economic ties.

The use of jet in the prehistoric period offers a fascinating glimpse into the ancient cultures’ artistic, spiritual, and practical sensibilities. Although our understanding of specific prehistoric societies and their usage of jet may remain limited, the archaeological evidence provides valuable insights into the significance of this unique gemstone in the daily lives and belief systems of our distant ancestors.

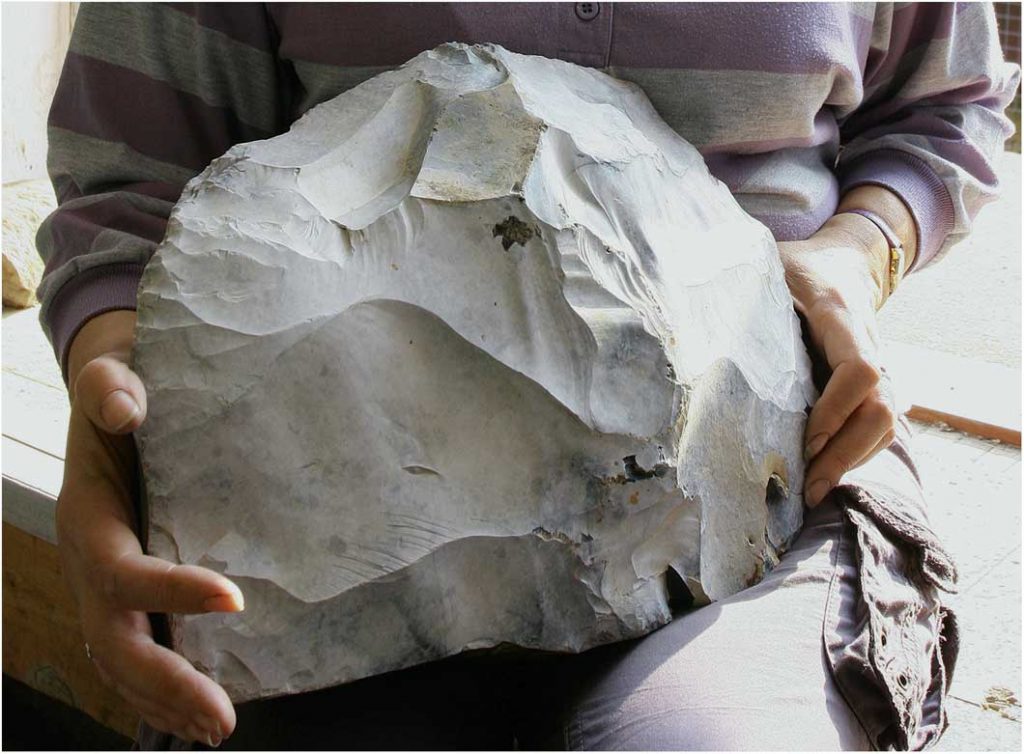

A significant portion of true jet used in Britain from the Bronze Age to the Roman Period originated from the Whitby coastline of North Yorkshire. This jet likely eroded from the Upper Lias (Lower Jurassic) shales, including the thin Upper and Lower Jet Beds, which constitute part of the cliff strata in the region. Jet beads production might have been facilitated by mining the most delicate laminae of fresh jet from these shales. However, specific extractive sites from this period have not been identified.

Prehistoric

The primary jet source during prehistoric times is believed to have come from natural deposits or surface collections rather than extensive mining operations. Some regions known for prehistoric jet use include the area around Whitby, in North Yorkshire, England, is renowned for its high-quality jet. Jet artifacts dating back to the Neolithic and Bronze Age have been found in this region, suggesting that the ancient inhabitants may have collected jet from the beach or small surface outcrops.

The Forest of Dean, located in Gloucestershire, England, is another region where jet artefacts have been found. As mentioned earlier, jet was associated with the Scowles, which are natural formations of fossilised wood that were later exploited by prehistoric communities for various purposes.

Jet was an important grave good accompanying inhumation burials in Early Bronze Age barrows. X-Ray Fluorescence analysis indicates that most of the jet beads found, such as those in the Kill y Kiaran necklace discovered in a Scottish barrow, were made of Whitby jet. Some beads might have been made from cannel coal, a similar but less lustrous form of mineral coal sourced from the Lias of the Dorset coast.

It is important to note that the evidence for prehistoric jet mines is scarce, and much of what we know about prehistoric jet usage comes from discovering jet artefacts in archaeological sites. If they existed, the exact locations of prehistoric jet mines might remain hidden due to the passage of time and the challenges of archaeological investigation. As research and archaeological techniques continue to evolve, there may be future discoveries that shed more light on the ancient sources and methods of jet acquisition during prehistoric times.

Roman