The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

Promotional Video – Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – The Vallum (Maiden Way)

Extract From Book……………………… Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – The Vallum

Contents

Introduction

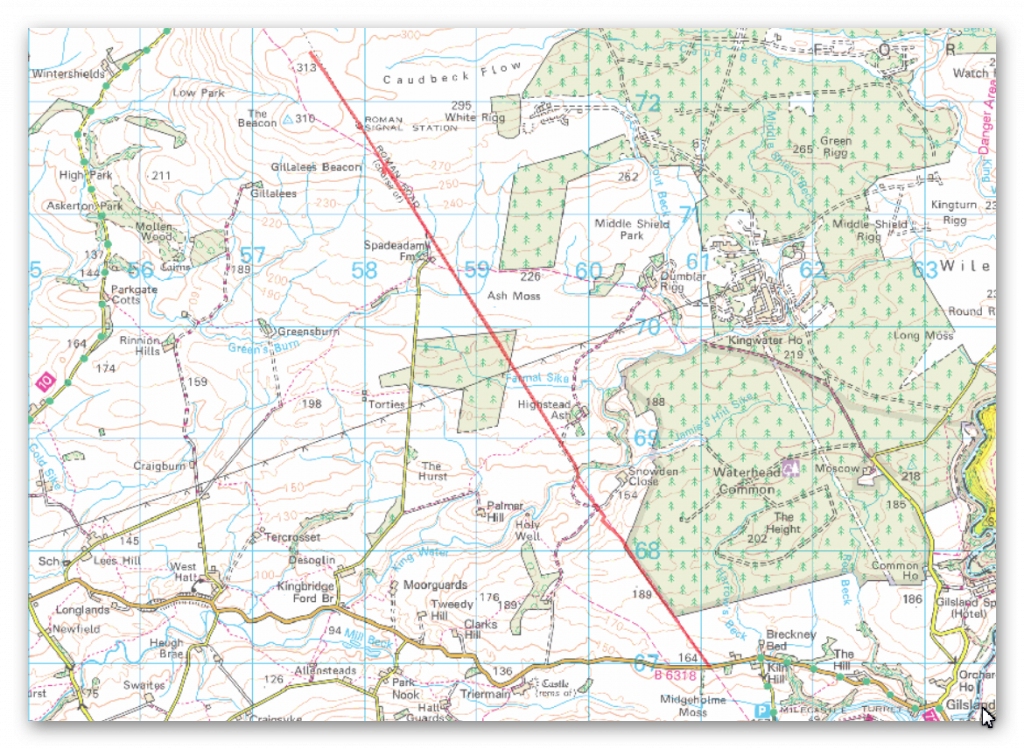

In this deep-dive case study, we explore the so-called Maiden Way—a Roman road stretching 6.58 km from the B6318 to the moorlands near High House, featuring not just a road but also a Roman signal station and a post-medieval settlement. Officially recognized as monument HE:1018242, this route is traditionally believed to have linked the Hadrian’s Wall fort at Birdoswald to the more remote outpost of Bewcastle.

The road winds over Waterhead Common and Gillalees Beacon, where a signal station known as Robin Hood’s Butt perches with a clear line of sight to Birdoswald, hinting at a rapid communication system used in the Roman period. But the picture gets muddier as we examine the path’s quirks and oddities—such as its abrupt changes in direction, inconsistencies in width, and curious detours around natural features like river valleys.

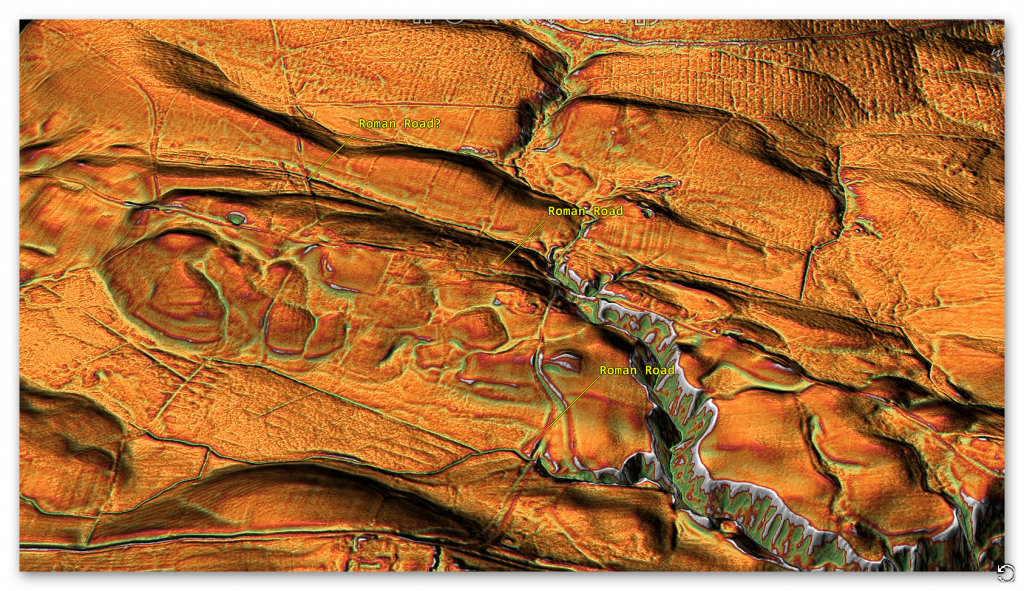

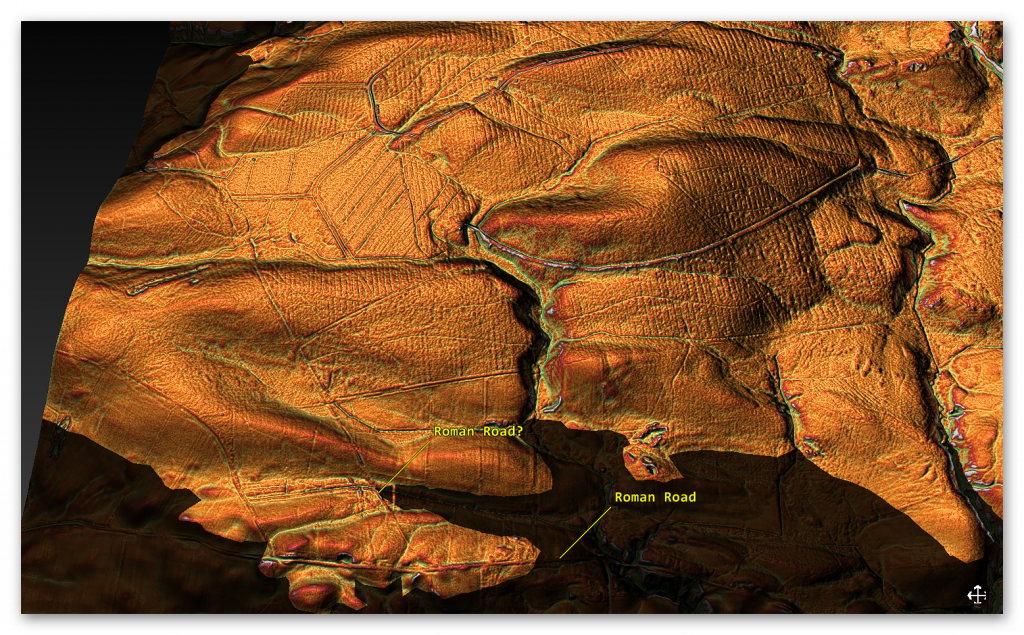

What’s especially compelling is the suggestion that the Maiden Way might not be entirely Roman at all. Archaeological evidence describes the road being built on top of earlier earthworks—raised banks known as aggers, hollow ways, and terraced slopes. Such features are commonly associated with prehistoric dykes, raising the tantalizing possibility that Roman engineers simply repurposed a much older network.

The signal station and adjacent Beacon Pasture settlement reveal layered usage through time. From turf-covered stone platforms to lazy-bed agriculture, we see a landscape that evolved, was reused, and finally abandoned by the mid-19th century. Yet the road’s twisty turn—particularly its eastward and then southward veer near the river valley—suggests Roman pragmatism encountering ancient geography and adapting rather than conquering.

So, was the Maiden Way a Roman masterpiece of engineering… or just a makeover of a prehistoric thoroughfare?

As with other “Roman” features like the Vallum and Military Way, the truth might be a lot more ancient—and a lot more complicated—than it first appears.

Hadrians Wall

Traditional archaeologists and archaeological establishments like English Heritage suggest that:

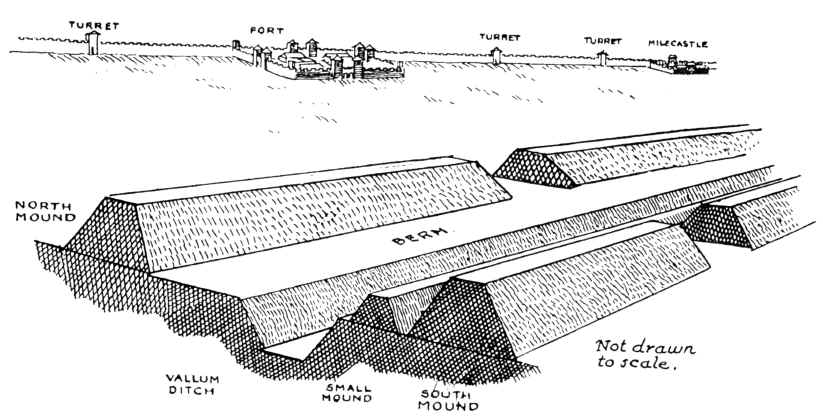

The Vallum is a massive earthwork constructed shortly after Hadrian’s Wall itself and lying just south of it. Many visitors confuse the Vallum with Hadrian’s Wall itself because it’s such an obvious and impressive feature in the landscape.

In fact, the Vallum is made up of several different elements – a ditch around 6 metres wide and 3 metres deep; two mounds either side of the ditch about 6 metres wide and 2 metres high and set back from the ditch by around 9 metres; and often a third mound on the southern edge of the ditch. The whole complex is around 36 metres across. Usually, the Vallum runs close behind the Wall but in the rocky and hilly central section the Vallum lies up to 700 metres from the Wall. ( Maiden Way)

Crossing points seem to have been located south of each of the forts along Hadrian’s Wall and near several of the milecastles. Evidence from the excavated Vallum crossing at Benwell in Newcastle shows these crossing points had impressive monumental gateways.

The Vallum’s purpose is unclear. Many archaeologists think it marks the southern boundary of a military zone with the Wall itself forming the northern boundary. This would have helped protect the rear of the Wall and its associated military installations, with civilian access being closely controlled. The gateway at Benwell supports this idea. The numerous gateways along the Wall at forts and milecastles suggest that the frontier was intended as much to control movement as to provide a defensive line. Traders would have moved goods across the frontier but their movements would have been controlled and their goods taxed.

Relatively soon after it was constructed, some 20 to 30 years perhaps, the Vallum seems to have lost its function – the mounds were cut through and the ditch filled in at fairly regular intervals. It was out of use by the time the forts along the Wall were re-commissioned in the late second century AD following the return of the garrison from the Antonine Wall.

Sadly, these ideas that have been constructed over the last 200 years are somewhat questionable. Within the book we look at associated aspects of this area like Military Way which was supposed to be constructed to patrol the so-called ‘Military Zone’ – to find that:

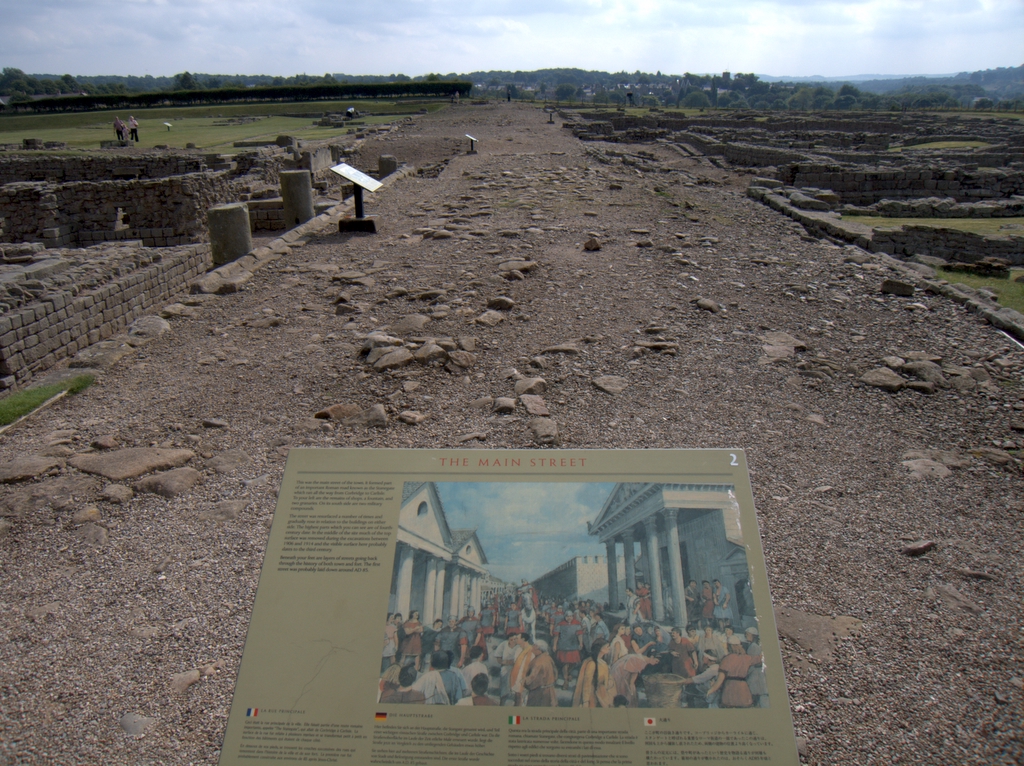

That over 50% of Military Way does not exist as a separate road, as described by archaeologists. Instead, the perceived road is fragmented and only becomes ‘alive’ as an independent road when the Vallum separates from the wall at any distance.

This might give us a clue to the function of this rough and wonky road, as the stone for the wall would have needed to be delivered by cart if the Vallum canal was not available.

As for the Stanegate that was supposed to connect to the main forts in the area as a ‘defensive shield’ we actual found that it is very little to no evidence of the ‘Stanegate Roman Road’, which (according to the current theory proposed by English Heritage) ‘consolidated as a frontier’ during the late first and early second century AD and helped crystallise Roman tactics and military expectations in the area.

This evidence is compounded when you release that of the 80mile border from coast to coast – Stonegate, at best, covers just 38.1 miles (47%) of the ‘defensive gap’, and hence suggestions of extension over and above the existing line existed (even without support from OS maps). Moreover, the research has shown the ‘raw’ Stanegate road without the ‘hidden’ parts below the B-roads – we are only looking at 20% of the declared road being visible on LiDAR maps.

Stanegate Road (when not part of an existing B-road system) is inconsistent in width and structure -moving from bank track to road with two ditches on each side to a ditch with two banks far from straight and usually starts and ends in ravens.

Most Forts and the Stanegate are not found to connect (with intersecting sub-roads) on only two occasions, and the rest show no connection. Moreover, later ‘temporary’ camps also did not connect with the road – which questions whether (a defence line) was its purpose.

Moreover, this would then question the ‘myth’ of using the Stanegate as a ‘boundary’ for withdrawing troops from Scotland in the first century AD is correct. And whether the River Tyne (which most of these Forts sit upon) was used as a more practical and effective boundary/defence.

This ‘myth buster’ will not surprise many in academia as it has been ‘hinted’ at for some time (but not acted upon it by updating the literature), as we see from Symonds et al.

“The question of whether a road even existed when the fortlets were founded is by default an existential one for the notion that they provided highway protection. But even if the metalled road does post-date the fortlets, a reasonably robust thoroughfare of some form must have existed from at least the mid AD 80s to service Vindolanda. The question is not whether there was a road, but whether it was metalled when the fortlets were founded.” Symonds, M. (2017). Hadrian’s Wall. In Protecting the Roman Empire: Fortlets, Frontiers, and the Quest for Post-Conquest Security (pp. 95-132)

Moreover, even if Stanegate was not built as suggested, it exists in parts, and it looks prehistoric (by design) as it relies heavily on ravens that start and end sections of the Stanegate sections; its sunken structure in parts is unfamiliar to traditional Roman Road design.

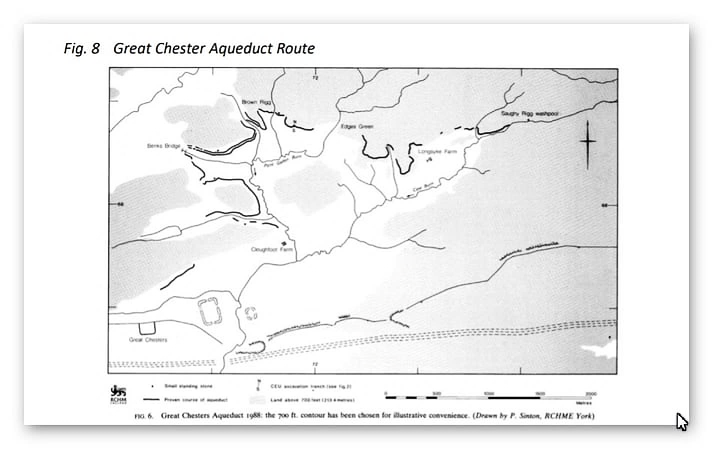

As for other famous ‘Roman Features Such as the Great Chesters Aqueduct, again we find not only is the origin questionable but as it located supposedly fully in ‘hostile territory – they its usefulness win conflict would be limited.

It is clear from the LiDAR research that the suspected Roman Aqueduct is not as it seems. This is not the first examination to spread doubt about the scale and origin of this feature in the landscape – MacKay, D. A. (1990). The Great Chesters Aqueduct: A New Survey. Britannia, 21, 285–289. Also shows an incomplete map of this aqueduct.

Mackey failed to find in their survey that the Aqueduct changed size, and the path suggested had no identifiable remains of the bridges required to make this Aqueduct work.

Our more detailed findings indicate that the topology of the aqueduct suggests that it would need to go uphill at several points without any powered assistance (like a siphon) and so is mechanically unsound. Our finding has found that the use of ‘Dykes’ in this area and some connecting to this Aqueduct feature is new. We have also shown that closer to the Fort it was supposed to supply, there were closed water sources which could be used and that the Fosse by the Wall was also a water supply.

We conclude that we found a prehistoric watercourse linked to their sophisticated ‘Dyke’ system. I would be bold to suggest that this was used for either agricultural purposes or maybe industrial, seeing the multiple sites of quarries associated and in the region of this feature.

Case Study – Maiden Way

Name: Maiden Way Roman road from B6318 to 450m SW of High House, Gillalees Beacon signal station and Beacon Pasture early post-medieval dispersed settlement

List UID: 1018242

The monument includes the earthworks and buried remains of a 6.58km length of the Maiden Way Roman road together with the earthwork remains of Gillalees Beacon Roman signal station, also known as Robin Hood’s Butt, and Beacon Pasture early post-medieval dispersed settlement.

The Maiden Way connected the Hadrian’s Wall fort at Birdoswald with the fort at Bewcastle 9.6km to the north.

After leaving Birdoswald the road climbs gradually over Waterhead Common and Ash Moss to its highest point on the moorland of Gillalees Beacon where, a short distance south of the summit, remains of the Roman signal station stand. Beacon Pasture settlement overlies the Roman road and lies on the moorland a short distance south of the signal station.

Construction of Birdoswald and Bewcastle forts commenced during the early 120s AD and the road connecting the two forts must also have been built at this time.

Where the road survives as an earthwork it can be seen either as a raised bank known as an agger upon the top of which the road surface was built, or as a hollow way where erosion of the road surface may have occurred or where the Roman engineers have taken the road through a cutting.

It is also visible as a terrace running diagonally down the steepest hillslope in order to ease the gradient. Flanking ditches for drainage purposes ran either side of the road; where not infilled by natural processes these ditches survive as earthworks.

Where they are infilled their location can frequently be identified by changes in the vegetation cover where the deeper, damper soil has encouraged a lusher growth. The finest surviving stretch of agger and flanking ditch lies a short distance north of the B6318. Here a length of agger approximately 200m long measures 10m wide at the base and 5m wide at the top and survives up to 0.8m high.

The western ditch at this point measures 2m wide by 0.2m deep. Limited excavations of the road further north have shown it to be formed of two courses of large stones laid flat over which a layer of small stones was laid to form the road’s metalled surface. The road was found to be well cambered and has large kerbstones.

These excavations also found that the width of the road surface was not constant and varied between 3.7m and 4.6m. In places, particularly on the higher moorland, the road and its ditches lie buried beneath vegetation cover and no surface remains are visible. Here the course of the road can still be followed quite clearly where modern drainage channels have been cut through it exposing the road’s stone foundations.

Gillalees Beacon signal station lies immediately west of the Roman road. It survives as a rectangular earth and stone mound up to 2.5m high surrounded by a shallow ditch with a causeway on the east side which gave access directly from the road. Antiquarian investigation found the stone-built structure to measure approximately 6m by 5.5m externally with walls standing ten courses high.

The signal station is positioned to be in full view of Birdoswald fort 6.5km to the south and its function would have been to rapidly convey information to the fort garrison if an enemy was approaching from the north. Beacon Pasture early post-medieval settlement consists of three rectangular enclosures, one north of and two south of the Roman road. The house was originally built of stone and is now visible as a turf-covered platform of stone tumble measuring 13.5m by 6.7m. It lies alongside the road overlapping the edge of the northern enclosure and its position adjacent to the road indicates that this part of the Maiden Way remained in use during the early post-medieval period.

The southern enclosure measures 44m by 29m and contains ridge and furrow, indicating that arable cultivation took place here, while the smaller northern enclosure contains lazy-beds (raised earthen mounds) about 1.5m wide on which crops were grown, and thus also attests to arable cultivation.

The central enclosure measures 34m by 32m and is interpreted as a stockpen. The settlement had been abandoned by 1854.

Between NY60286811 – NY59886877 the protection follows the actual line of the road and not that suggested by the Ordnance Survey.

The road is visible as an earthwork between NY60286811 – NY60136831 and between NY59906865 – NY59886877.

Between NY60136831 and Slittery Ford at NY59896862 the road is interpreted as surviving as a buried feature.

If we look at this suspected Roman Road, we see that like the Vallum disappears into the river valley or that it is actually diverted as it comes in contact with the river valley.

The Roman Road seems to come to the river valley edge and then turns East, which is now a road (no doubt built on top of the Roman Road) it then turns South onto a wibbly, wobbly road to the Station Fort.

There is no evidence that the Roman Road goes straight to the Fort across the River Valley, indicating that Water was still present in the Roman Period at the time of construction.

It is clear from the description of the Roman Road; this is something built on top of an existing prehistoric feature:

“Where the road survives as an earthwork it can be seen either as a raised bank known as an agger upon the top of which the road surface was built, or as a hollow way where erosion of the road surface may have occurred or where the Roman engineers have taken the road through a cutting.” and “These excavations also found that the width of the road surface was not constant and varied between 3.7m and 4.6m. ”

Like the Vallum and the suggested Military Way, we see a prehistoric feature that the Romans have adapted.

This was an extracts from the NEW Book Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke available on Amazon as a FULL COLOUR HARD BACK (£49.95) or a ECONOMY (£9.99) SOFTBACK black and white VERSION – it is also available as a KINDLE (£2.99) book. For further information about our work on Prehistoric Britain visit our WEBSITE or VIDEO CHANNEL.

Product details

- ASIN : B0BN7PD6BS

- Publisher : Independently published (24 Nov. 2022)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 477 pages

- ISBN-13 : 979-8358524187

- Dimensions : 15.24 x 3.33 x 22.86 cm

- Illustrations: 350+

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

(Maritime Diffusion Model for Megaliths in Europe)

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?