The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 References

- 3 Challenging the Migration Myth: Einkorn Wheat, Ancient Mariners, and the True Timeline of Megalithic Europe

- 4 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 5 Further Reading

- 6 Other Blogs

Introduction

Challenging the Migration Myth: Einkorn Wheat, Ancient Mariners, and the True Timeline of Megalithic Europe

For decades, the “migration model” has dominated the narrative of early farming in Europe, portraying agriculture as spreading westward through the gradual movement of farming communities from the Middle East. However, recent discoveries, including findings at Bouldnor Cliff, evidence of the world’s oldest boatyard in Wales, and new analyses of radiocarbon dates, are reshaping this long-held theory. These groundbreaking insights reveal a far more intricate picture of prehistoric Europe, characterized by advanced maritime trade networks and megalithic monuments built millennia earlier than previously believed. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

The Einkorn Wheat Discovery at Bouldnor Cliff

Over a decade ago, archaeologists uncovered traces of domesticated einkorn wheat at Bouldnor Cliff, a submerged Mesolithic site off the British coast. Radiocarbon dating confirmed that this discovery dates back over 8,000 years, predating the arrival of farming in Britain by 2,000 years. This challenges the idea of agriculture’s slow and linear spread and suggests that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Britain accessed agricultural products through complex trade networks extending to the Middle East.

The presence of einkorn wheat, a domesticated crop with origins in the Middle East, implies that prehistoric societies had advanced seafaring capabilities. Evidence of planked wooden boats at the site contradicts the traditional view of Mesolithic communities as primitive hunter-gatherers using rudimentary dugout canoes. Instead, these boats could navigate long distances and enabled sophisticated trade networks. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

The Oldest Boatyard: Catamarans and Maritime Innovation

Supporting this narrative is the discovery of what has been called the “oldest boatyard in the world,” located in Wales. Initially thought to be channels for dugout canoes, a reevaluation using LiDAR mapping revealed that these were slipways for catamarans—a remarkable technological advancement not recognized in Europe until thousands of years later.

These catamarans, equipped with outriggers, could transport heavy materials over water. This innovation aligns with the movement of large stones, such as those transported from the Preseli Hills to Stonehenge. The revised dating of this boatyard to around 8,000 BCE supports the theory that maritime trade and technological sophistication existed far earlier than previously believed. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Radiocarbon Dating and the Revised Timeline of Megalithic Europe

The timeline of megalithic construction in Europe is also being reexamined. A comprehensive study of over 2,400 radiocarbon dates suggests that megalithic construction originated in northwestern France around 4500 BCE and spread via coastal and maritime networks. However, a closer analysis of early contexts points to an even earlier timeline, with sites like Carnac and Stonehenge showing evidence of activity as far back as 8300 BCE.

These findings challenge the traditional narrative, which dates megalithic monuments to 5000 years later. Mesolithic hearths, tools, and other features suggest that these sites were part of a widespread maritime culture, further emphasizing the advanced capabilities of these prehistoric societies. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Implications for Prehistoric Migration and Trade

The implications of these discoveries are profound and dismantle the outdated “migration model” as the sole explanation for the spread of agriculture and culture. The evidence suggests:

- Sophisticated Maritime Trade: Prehistoric societies were interconnected through vast trade networks, enabling the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies.

- Advanced Seafaring Technology: Using planked boats and catamarans demonstrates significant maritime innovation, facilitating long-distance travel and trade.

- Pre-Agricultural Networks: Long-distance trade routes likely predated the adoption of farming, serving as conduits for agricultural products and cultural exchanges.

- Mesolithic Origins of Megaliths: Monumental structures such as Stonehenge and Carnac were built much earlier than previously believed during the Mesolithic period.

These findings reveal a more nuanced view of prehistoric societies, characterized by ingenuity and technological sophistication rather than the simplistic hunter-gatherer versus farmer dichotomy. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Rethinking the Past

Despite the mounting evidence, some academic communities have resisted reevaluating entrenched narratives. Discoveries at sites like Craig Rhos-y-Felin, where Mesolithic carbon dates suggest an early quarrying activity, have been dismissed in favour of later Neolithic timelines. Similarly, Mesolithic post holes at Stonehenge have been downplayed as unrelated artefacts rather than being recognized as evidence of early monumental construction. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

This reluctance highlights the need for a paradigm shift in archaeological thought. By embracing new perspectives, we can:

- Recognize the complexity and interconnectedness of prehistoric societies.

- Acknowledge the central role of maritime activity in shaping early European cultures.

- Employ more accurate dating methods, moving beyond relying solely on Bayesian statistical modeling.

- Encourage open-mindedness in interpreting data, ensuring discoveries are not dismissed for contradicting established theories.

The Call for a New Paradigm

The einkorn wheat discovery, the world’s oldest boatyard, and revised megalithic timelines collectively demand reevaluating our understanding of prehistoric Europe. These findings reveal a world where maritime trade, advanced engineering, and cultural innovation flourished long before the arrival of farming communities. They challenge the outdated “migration model” and call for a broader, more inclusive framework that better reflects the ingenuity of our ancestors.

By shifting our perspective, we can uncover a richer, more accurate account of prehistoric Europe—one that honours the achievements of early seafarers and their contributions to the development of human civilization. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

References

By Michael BalterFeb. 26, 2015 , Science Magazine.

Hunter-gatherers may have brought agricultural products to the British Isles by trading wheat and other grains with early farmers from the European mainland. That’s the intriguing conclusion of a new study of ancient DNA from a now submerged hunter-gatherer camp off the British coast. If true, the find suggests that wheat made its way to the far edge of Western Europe 2000 years before farming was thought to have taken hold in Britain.

The work confronts archaeologists “with the challenge of fitting this into our worldview,” says Dorian Fuller, an archaeobotanist at University College London who was not involved in the work.

For decades, archaeologists had thought that incoming farmers from the Middle East moved into Europe beginning about 10,500 years ago and replaced or transformed hunter-gatherer populations as they moved west, not reaching Britain until about 6000 years ago. But that worldview had already undergone some modifications. Recent discoveries, for example, have shown some incoming farmers coexisted with the hunter-gatherers already living in Europe rather than quickly replacing them. In 2013, researchers reported that, beginning about 6000 years ago, farmers and hunter-gatherers had both buried their dead in the same cave in Germany and continued to do so for 800 years, suggesting that the two groups were in close contact. More controversially, researchers claimed that about 6500 years ago hunter-gatherers in Germany and Scandinavia may have acquired domesticated pigs from nearby farmers. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

The new findings promise to further upset the scenario that farming steadily marched from east to west. A team led by Robin Allaby, a plant geneticist at the University of Warwick in the United Kingdom, was looking for the earliest evidence of domesticated plants in the British Isles. The researchers decided to take a gander at an underwater site called Bouldnor Cliff, 250 meters offshore from the hamlet of Bouldnor in the northwest corner of the Isle of Wight. (The island is in the English Channel just off Britain’s southern coast.)

Bouldnor Cliff, located 11 meters below the water’s surface, was discovered in 1999, when, as the United Kingdom’s Maritime Archaeology Trust puts it on its website, “a lobster was seen throwing Stone Age worked flints from its burrow.” Archaeologists have been working there ever since. The site was clearly occupied by hunter-gatherers, who may have built wooden boats. Allaby’s team took four core samples of sediments from a section of the site littered with burnt hazelnut shells apparently left by the hunter-gatherers and subjected the samples to both radiocarbon dating and ancient DNA analysis. The samples’ wood and plants were dated to between 8020 and 7980 years ago, after which the site was inundated by the rising seas that created the English Channel and separated Britain from France.

For the ancient DNA analysis, the team used methods pioneered by paleogeneticist Eske Willerslev of the University of Copenhagen to recover and sequence genetic material left behind in sediments even after the plants that originally contained it have disintegrated. As might be expected, Allaby and his colleagues found DNA from a wide variety of trees and plants known to have populated southern Britain 8000 years ago, including oak, poplar, and beech, along with various grasses and herbs. But the team also got a big surprise: Among the DNA samples were two types of domesticated wheat that originated in the Middle East and that have no wild ancestors in northern Europe. That meant they must have been associated with the original spread of farming from the Middle East, beginning about 10,500 years ago, rather than domesticated locally. Yet many archaeologists assume that by 8000 years ago farming was no further west than the Balkans region and modern Hungary. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

The researchers performed a number of tests to eliminate the possibility of contamination from modern wheat, including trying to sequence DNA from the chemical solutions it used in the experiments, but no plant sequences were detected. The only possible conclusion was that the domesticated wheat had actually come from the hunter-gatherer site at Bouldnor Cliff, the team reports online today in Science.

“The paper is methodologically impressive,” Fuller says. Willerslev agrees: “The study is quite convincing,” he says, adding that loose DNA from sediments will provide “some of the earliest detectable evidence for farming” because cereal grains themselves are less likely to be preserved. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

So how did domesticated wheat get to Britain 2000 years before people began to farm there? Allaby’s team does not think the hunter-gatherers cultivated wheat themselves, because no wheat pollen was found in the samples—as should have been expected if the cereal had been allowed to go through its entire life cycle, including flowering.

The team proposes that farming might have spread to western France earlier than had been thought, up to 7600 years ago, and thus only a 400-year gap would have to be explained. But Peter Rowley-Conwy, an archaeologist at the Durham University in the United Kingdom, rejects that suggestion. “The authors do not do justice to the chronology of the spread of agriculture,” he complains, noting that “thousands of directly radiocarbon-dated cereal grains” argue against farming in Western Europe that early. “One DNA study of this kind is just not enough to overturn all this.”

Another possibility, Allaby says, is that the nomadic hunter-gatherers of southern Britain roamed much farther into the European mainland than previously realized, picked up wheat or wheat products from farmers to the east, and brought them back to Britain. He also suggests that the conventional dating of the spread of agriculture, based on clearly detectable cereal grains, might be missing earlier samples.

Allaby may well be right, says Greger Larson, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. “Are we underestimating the degree to which there were exchange networks between farmers and hunter-gatherers which extended far across time and space? Maybe the only way to pick them up is from DNA signatures.”

Yet Fuller says that the new finds do not necessarily indicate that the spread of farming needs to be radically redated. Rather, he suggests, small-scale pioneers of both farmers and hunter-gatherers may have been “operating beyond the frontier of farming” as it spread west in a wave of advance. The wheat might have been part of trade or cultural exchanges between them. Just as rare spices from the east are regarded as valuable commodities today, Fuller says, the wheat at Bouldnor Cliff might have been symbolically charged and seen as “rare, exotic, and valuable,” rather than something to be eaten daily. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Clearly, the traditional migration model is, quite frankly – DEAD!

Timeline of Main Events (BCE)

Note that many of these events are based on radiocarbon dating and are subject to interpretation and potential revisions. The sources provided offer a specific perspective that questions some established archeological timelines. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

- 8800 BCE: Likely date of construction of Saint Michel site (France), marking the earliest megalithic construction mentioned. The “Maritime Diffusion Model” suggests seafaring people were building megaliths this early.

- 8750 BCE: Likely date of construction of Orquinha dos Juncais site (Portugal), another early megalithic site.

- 8560 BCE: Likely date of construction of Curacchiaghiu site (Corsica), one of the earliest megalithic constructions according to the maritime diffusion model.

- 8328 BCE: Likely date of construction of the Flintbek site (Germany).

- 8300 BCE: Proposed date for the construction of Stonehenge by the author, predating other accepted timelines. This is based on the author’s idea of a maritime diffusion.

- 8080 BCE: Likely date of construction of Casinha Derribada site (Portugal), another early megalithic site

- 8000 BCE: Likely date of construction of Madorras I site (Portugal), suggesting a concentration of early megalithic construction in this area

- 7985 BCE: Likely date of construction of Le Souc´h site (France)

- 7960 BCE: Likely date of construction of Tremedal site (Portugal)

- 7740 BCE: Likely date of construction of Orca de Merouços site (Portugal)

- 7670 BCE: Likely date of construction of Sarceaux site (France)

- 7660 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cabeçuda site (Portugal)

- 7615 BCE: Likely date of construction of the Gökhem 94:1 site (Sweden), the earliest Megalithic site in Scandinavia by far.

- 7580 BCE: Likely date of construction of Barkaer site (Denmark)

- 7550 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cabeço da Arruda (Muge), Ribatejo site (Portugal)

- 7500 BCE: Sketewan site (Scotland), showing evidence for an early phase of megalithic activity in the region

- 7440 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cuevo de los Murciélagos site (Spain)

- 7300 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cabeço da Amoreira (Muge), Ribatejo site (Portugal)

- 7240 BCE: Likely date of construction of Moita do Sebastião (Muge), Ribatejo site (Portugal)

- 7230 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cabeço das Amoreiras, Alentejo site (Portugal), the first of multiple sites in this area.

- 7200 BCE: Likely date of construction of Arapouco site (Portugal)

- 7165 BCE: Likely date of construction of Hoëdic site (France)

- 7140 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cova da Onça (Magos), Ribatejo site (Portugal), indicating that the maritime diffusion model covered many areas of Portugal at this time.

- 7060 BCE: Likely date of construction of L’Ubac site (France)

- 7030 BCE: Likely date of construction of Châ de Carvahal 1 site (Portugal)

- 6990 BCE: Likely date of construction of Quélarn site (France)

- 6925 BCE: Likely date of construction of Ballymcdermot (Ireland), the earliest Megalithic site in Ireland by far.

- 6910 BCE: Likely date of construction of Châ da Parada 3 site (Portugal)

- 6835 BCE: Likely date of construction of Knowth 1 site (Ireland)

- 6760 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cabeço do Pez, Alentejo (Portugal)

- 6740 BCE: Likely date of construction of Téviec site (France)

- 6730 BCE: Likely date of construction of Carvahal site (Portugal)

- 6670 BCE: Likely date of construction of Balnuaran of Clava (Scotland).

- 6575 BCE: Likely date of construction of Chan de Prado 6 site (Spain)

- 6570 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cabras site (Spain)

- 6565 BCE: Likely date of construction of Valdemuriel 2 site (Spain)

- 6500 BCE: Likely date of construction of Carrowmore site (Ireland).

- 6420 BCE: Likely date of construction of Grotte de Puechmargues site (France).

- 6370 BCE: Likely date of construction of Samouqueira 1 site (Portugal).

- 6360 BCE: Likely date of construction of Castelhanas site (Portugal).

- 6330 BCE: Likely date of construction of Correio-Mór site (Portugal)

- 6310 BCE: Likely date of construction of Outeiro de Ante 1 site (Portugal)

- 6305 BCE: Likely date of construction of Er Grah site (France)

- 6300 BCE: Likely date of construction of Biggar Common site (Scotland)

- 6250 BCE: Likely date of construction of Dissignac site (France).

- 6210 BCE: Likely date of construction of Table des Marchands (France), along with Tertre de Lomer and Figueira Branca and numerous other Megalithic sites.

- 6200 BCE: Likely date of construction of Vallon Carbonel site (France)

- 6190 BCE: Likely date of construction of Font de la Vena and La Chaise sites (France).

- 6180 BCE: Likely date of construction of Ascott-under-Wychwood (England) based on the Maritime Diffusion Model, being the earliest Megalithic site in the UK.

- 6140 BCE: Likely date of construction of Skorba (Maltese Archipelago)

- 6100 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cabritos 3 site (Spain)

- 6090 BCE: Likely date of construction of Passy Sablonnière site (France).

- 6060 BCE: Likely date of construction of Lupawa (Poland)

- 6050 BCE: Likely date of construction of Coto dos Mouros (Portugal)

- 6030 BCE: Likely date of construction of Alto da Barreira (Portugal)

- 6022 BCE: Likely date of construction of Menhir de Meada (Portugal).

- 6006 BCE: Likely date of construction of Boghead site (Scotland).

- 5995 BCE: Likely date of construction of Haut Mée site (France).

- 5970 BCE: Likely date of construction of Areita 1 site (Spain).

- 5960 BCE: Likely date of construction of Passy Richebourg site (France)

- 5940 BCE: Likely date of construction of Goumoizère site (Switzerland)

- 5920 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cerro Virtud (Spain), Cova de I´Avellaner (Spain) and Outeiro de Ante 2 site (Portugal).

- 5890 BCE: Likely date of construction of Chan da Cruz 1 site (Portugal).

- 5870 BCE: Likely date of construction of El Padró II site (Spain) and Kilpatrick site (Scotland).

- 5860 BCE: Likely date of construction of Bougon/Chirons site (France)

- 5840 BCE: Likely date of construction of Kercado site (France)

- 5835 BCE: Likely date of construction of Lannec er Gadouer site (France)

- 5820 BCE: Likely date of construction of Monte Areo VI site (Spain)

- 5810 BCE: Likely date of construction of Alcalar 7 site (Portugal), Larrarte and Larratbi sites (Spain).

- 5805 BCE: Likely date of construction of Monte Maninho site (Portugal)

- 5800 BCE: Likely date of construction of Île Guennoc III and Îlot de Roc´h Avel sites (France)

- 5780 BCE: Likely date of construction of Outeiro de Ante 3 site (Portugal).

- 5750 BCE: Likely date of construction of Barnenez site (France)

- 5750 BCE: Likely date of construction of Azutan site (Spain)

- 5730 BCE: Likely date of construction of Hazleton North (England).

- 5720 BCE: Likely date of construction of Castelo Belinho (Portugal).

- 5710 BCE: Likely date of construction of Castillejo site (Spain).

- 5690 BCE: Likely date of construction of Vierville/La Butte á Luzerne site (France)

- 5680 BCE: Likely date of construction of Catasol 2 site (Spain).

- 5670 BCE: Likely date of construction of Valdemuriel 1 site (Spain).

- 5660 BCE: Likely date of construction of Le Grée de Cojoux site (France) and Sandun site (Spain).

- 5650 BCE: Likely date of construction of Petit Mont site (France) and Campo del Hockey site (Spain)

- 5640 BCE: Likely date of construction of Caune de Belesta site (France)

- 5630 BCE: Likely date of construction of Monte da Olheira site (Portugal).

- 5615 BCE: Likely date of construction of Balloy, Les Réaudins site (France).

- 5590 BCE: Likely date of construction of Les Fouaillages site (France).

- 5580 BCE: Likely date of construction of Les Erves and Ty Floc´h, St. Thois sites (France).

- 5570 BCE: Likely date of construction of Sarnowo site (Poland)

- 5560 BCE: Likely date of construction of La Hoguette site (France) and Gruta dos Escoral (Portugal).

- 5550 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cleaven Dyke (Scotland) and Mestreville (France).

- 5545 BCE: Likely date of construction of Lyse 7 site (Sweden).

- 5540 BCE: Likely date of construction of Bòbila Madurell site (Spain), Chenon and Mámoa do Monte: dos Marxos sites (Portugal).

- 5530 BCE: Likely date of construction of Châ da Parada 4 site (Portugal).

- 5500 BCE: Likely date of construction of Outeiro de Gregos 2 site (Portugal), Boeriza 2 and Péré, tumulus C sites (France).

- 5490 BCE: Likely date of construction of Larcuste II and Beg-an-Dorchem sites (France) and Monte Revincu, Dolmen de Casa di l´Urca and Hayas I sites (Corsica)

- 5470 BCE: Likely date of construction of Changé, (Saint Piat) site (France) and Monte Areo V site (Spain)

- 5450 BCE: Likely date of construction of Chã de Carvahal 1 site (Portugal)

- 5440 BCE: Likely date of construction of Portela do Pau 1 site (Portugal)

- 5435 BCE: Likely date of construction of Portela do Pau 2 site (Portugal).

- 5423 BCE: Likely date of construction of Contraguda site (Italy).

- 5410 BCE: Likely date of construction of La Hogue Bie (England), Monte Revincu, Dolmen de Cellucia (Corsica).

- 5405 BCE: Likely date of construction of Monte Revincu, Casa di L´Urcu, La Cabana 2, Monte Revincu, secteur de la Cima de Suarella sites (Corsica).

- 5404 BCE: Likely date of construction of Monte Areo XII site (Spain)

- 5400 BCE: Likely date of construction of Joaninha (Portugal) and Dolmen d`Arreganyats sites (Spain)

- 5390 BCE: Likely date of construction of Île Carn site (France)

- 5380 BCE: Likely date of construction of Brochtorff Circle (Maltese Archipelago).

- 5375 BCE: Likely date of construction of Fuentepecina site (Spain).

- 5365 BCE: Likely date of construction of Champ Châlon, Monument B1 site (France) and Lambourne Ground (England).

- 5360 BCE: Likely date of construction of Lameira de Cima 2 site (Portugal).

- 5355 BCE: Likely date of construction of Camp del Ginébre site (Spain) and Monte Revincu (Corsica).

- 5354 BCE: Likely date of construction of Najac site (France).

- 5340 BCE: Likely date of construction of Els Vilars and La Motte des Justices sites (France).

- 5330 BCE: Likely date of construction of Antelas (Portugal) and Mámoa do Monte: dos Marxos, Cova del Lladres and Prajou Menhir sites (Spain).

- 5329 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cotogrande 1 site (Spain)

- 5320 BCE: Likely date of construction of Alberite site (Spain) and Ventin 4 site (France).

- 5305 BCE: Likely date of construction of Rebolledo site (Spain)

- 5300 BCE: Likely date of construction of Trikuaizti I and Camp de la Vergentière sites (France).

- 5290 BCE: Likely date of construction of Ciella site (Spain)

- 5270 BCE: Likely date of construction of Furnas 1 and 2 and Igartza W sites (Spain).

- 5263 BCE: Likely date of construction of Le Déhus site (England).

- 5260 BCE: Likely date of construction of Meninas do Crastro 2 (Portugal)

- 5250 BCE: Likely date of construction of Neuvy-en-Dunois site (France) and Velilla 2 site (Spain).

- 5240 BCE: Likely date of construction of La Cabaña site (Spain)

- 5235 BCE: Likely date of construction of La Pierre Tourneresse site (France).

- 5230 BCE: Likely date of construction of Outeiro de Gregos 3 site (Portugal), Primrose Grange (Ireland) and Sierra Plana de la Borbolla 24 sites (Spain).

- 5220 BCE: Likely date of construction of Uglhöj and Jättegraven sites (Sweden).

- 5215 BCE: Likely date of construction of Slieve Gullion site (Ireland)

- 5200 BCE: Likely date of construction of Beckhampton Road site (England) Grotte des Cranes (France) and Velilla 3 sites (Spain).

- 5195 BCE: Likely date of construction of L´île Bono and Pena Ovieda I sites (Spain).

- 5190 BCE: Likely date of construction of Los Llanos 1 site (Spain), Dalladies (Scotland), and Horslip (England)

- 5175 BCE: Likely date of construction of La Llaguna A site (Spain)

- 5170 BCE: Likely date of construction of Wietrzychowice site (Poland)

- 5160 BCE: Likely date of construction of Picoto da Vasco (Portugal) and Cave de Cadaval sites (Portugal).

- 5155 BCE: Likely date of construction of El Miradero site (Spain)

- 5150 BCE: Likely date of construction of Dooey´s Cairn (Ireland), Borgstedt LA 22 (Germany), Morceo (Spain), Colombiers-sur-Seulles (France), and As Rozas 1 site (Spain).

- 5140 BCE: Likely date of construction of Krusza Zamkova site (Poland) and Liscuis I (France).

- 5135 BCE: Likely date of construction of La Llaguna D site (Spain).

- 5130 BCE: Likely date of construction of Senhora do Monte 3 (Portugal), Mina do Simão (Portugal), and Castello d’Araggio, C-Ar-4 sites (Corsica).

- 5125 BCE: Likely date of construction of Carapito 1 site (Portugal).

- 5115 BCE: Likely date of construction of Odarslöv site (Sweden)

- 5112 BCE: Likely date of construction of Mamoa do Castelo 1 site (Portugal)

- 5110 BCE: Likely date of construction of Monamore site (Ireland), Albersdorf: LA 56: Bredenhoop site (Germany).

- 5101 BCE: Likely date of construction of Coldrum site (England).

- 5100 BCE: Likely date of construction of Poulnabrone (Ireland), La Mina, Els garrofers del torrent de Sta. Maria sites (Spain).

- 5095 BCE: Likely date of construction of Montou site (France) and Örnakulla site (Sweden).

- 5090 BCE: Likely date of construction of Maes Howe (Scotland) and Sa ´Ucca de su Tintirriolu (Corsica) Dolmen de Tires Llargues, Champ Châlon, Monument B2 sites (France).

- 5080 BCE: Likely date of construction of Mosegården site (Sweden) and La Xorenga (Spain)

- 5078 BCE: Likely date of construction of San Benedetto site (Italy).

- 5070 BCE: Likely date of construction of Street House (England), Port Blanc (France) and Lochhill site (Scotland).

- 5060 BCE: Likely date of construction of Orca das Castenairas site (Portugal).

- 5055 BCE: Likely date of construction of Monte da Romea site (Portugal).

- 5050 BCE: Likely date of construction of Trefignath (Wales), Bjørnsholm (Denmark) and Gwernvale sites (Wales).

- 5045 BCE: Likely date of construction of Orca de Seixas (Portugal) and Ballybriest (Ireland)

- 5040 BCE: Likely date of construction of Monte Areo XV site (Spain)

- 5030 BCE: Likely date of construction of Champ Châlon, Monument C site (France) and Seamer Moor site (England).

- 5029 BCE: Likely date of construction of Broadsands site (England)

- 5025 BCE: Likely date of construction of Le Castellic site (France).

- 5020 BCE: Likely date of construction of Ponte da Pedra (Portugal).

- 5010 BCE: Likely date of construction of Châ da Parada 1 (Portugal) and Lindebjerg and Pedra Cuberta sites (Spain).

- 5005 BCE: Likely date of construction of Gökhem 17 site (Sweden) and Acon site (France).

- 4996 BCE: Likely date of construction of Vale de Rodrigo 3 site (Portugal).

- 4990 BCE: Likely date of construction of Orca da Penela 1 site (Portugal), Châ de Santinhos 2 site (Portugal) and Lameira de Cima 1, Algarão da Goldra sites (Portugal).

- 4980 BCE: Likely date of construction of Châ de Santinhos 1 and Pedra Moura sites (Portugal).

- 4970 BCE: Likely date of construction of Rustrup I site (Denmark) and Pen-y-Wyrlod site (Wales).

- 4969 BCE: Likely date of construction of Su Stampu e Giovnnicu Meli site (Corsica)

- 4965 BCE: Likely date of construction of Tulloch of Assery B (Scotland)

- 4960 BCE: Likely date of construction of Tully (Ireland) Willerby Wold site (England), Gladsax (Sweden) Meninas do Crastro 3 sites (Portugal), Cotobasero 2 and Orca dos Padrões sites (Portugal).

- 4955 BCE: Likely date of construction of Hirumugarrieta 2 site (Spain).

- 4950 BCE: Likely date of construction of West Kennet Long Barrow site (England), Dombate (Spain), Chamster Long (England), Costa dels Garrics de Caballol I Pinell and Grotta Filiestru sites (Spain).

- 4935 BCE: Likely date of construction of Dolmen de Menga site (Spain).

- 4930 BCE: Likely date of construction of Shanballeyedmond no 3 (Ireland), El Palomar, and Feixa del Moro sites (Spain).

- 4920 BCE: Likely date of construction of Monte d´Accodi (Italy), Rustrup II (Denmark) and Forno dos Mouros site (Portugal).

- 4910 BCE: Likely date of construction of Rude (Denmark)

- 4905 BCE: Likely date of construction of Vale de Rodrigo 2 (Portugal).

- 4900 BCE: Likely date of construction of Mound of the Hostages (Ireland) Millbarrow site (England), Grotta del Guano (Italy) Anta de Serramo, Collado Palomero 2 sites (Spain).

- 4897 BCE: Likely date of construction of West Tump site (England)

- 4890 BCE: Likely date of construction of Valtorp 2 site (Sweden)

- 4880 BCE: Likely date of construction of Ernes site (Scotland).

- 4875 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cotogrande 2 site (Spain)

- 4873 BCE: Likely date of construction of Knowth 17 (Ireland)

- 4870 BCE: Likely date of construction of Oldendorf IV and Champ Châlon, Monument A sites (Germany) , Pierre Virante II (France) and Bagnos site (France).

- 4860 BCE: Likely date of construction of Glenvoideau and Kleinenkneten 2 sites (Germany)

- 4852 BCE: Likely date of construction of Knowth site (Ireland).

- 4850 BCE: Likely date of construction of Bissee (Germany) , As Pereiras and Konens Høj sites (Denmark).

- 4840 BCE: Likely date of construction of La Vega 1 (Spain).

- 4830 BCE: Likely date of construction of Carreg Coetan (Wales), Montiou site (France), Kilham site (England).

- 4825 BCE: Likely date of construction of Kerléven (France), Storegard IV (Sweden) and Creggandevesky site (Ireland)

- 4820 BCE: Likely date of construction of Pena Ovieda and Dorna sites (Spain)

- 4817 BCE: Likely date of construction of Wayland´s Smithy site (England)

- 4810 BCE: Likely date of construction of South Stanwick (England) and Velilla 1 site (Spain).

- 4800 BCE: Likely date of construction of Tulloch of Assery A site (Scotland), Heberg (Sweden) and Ballintruer More site (Ireland)

- 4795 BCE: Likely date of construction of Grundoldendorf I site (Germany) and Lüdelsen 6 (Germany)

- 4785 BCE: Likely date of construction of Parknabinnia site (Ireland).

- 4780 BCE: Likely date of construction of Outeiro de Gregos 5 (Portugal) and Cabeceira 4 site (Portugal).

- 4770 BCE: Likely date of construction of Jerpoint West (Ireland), Carascal (Spain) and Sobreira 1 site (Portugal).

- 4765 BCE: Likely date of construction of Ashley Park site (England).

- 4760 BCE: Likely date of construction of South Street site (England).

- 4755 BCE: Likely date of construction of Rastorf site (Germany) and Drottning Hackas grav (Sweden), La Hameliniere site (France).

- 4750 BCE: Likely date of construction of Großenrode II site (Germany) and Peña Guerra 2 site (Spain).

- 4740 BCE: Likely date of construction of Rokaer and Bygholm Nørremark sites (Denmark) Casota do Páramo (Portugal) and Cova del Toixò site (Spain).

- 4735 BCE: Likely date of construction of Baunogenasraid site (Ireland).

- 4730 BCE: Likely date of construction of Easton Down, Bisshop´s Canning site (England), Collado Palomero 1 (Spain) and Kjeldbækgård site (Denmark).

- 4720 BCE: Likely date of construction of Arnillas and Torshøj sites (Spain), Moinhos de Vento site (Portugal) and Zberzyn site (Poland).

- 4717 BCE: Likely date of construction of San Bieito 2 site (Portugal)

- 4710 BCE: Likely date of construction of Port Charlotte site (Scotland) and Ølstykke site (Denmark)

- 4708 BCE: Likely date of construction of Canelles site (Spain).

- 4700 BCE: Likely date of construction of El Collado de Mallo (Spain), Cabeço de Arruda 2 (Portugal), Tustrup (Denmark) Fuente Morena and Le Stade sites (Spain).

- 4690 BCE: Likely date of construction of La Bruyere du Hamel and La Butte Saint Cyr (France) and Pujolet de Moja site (Spain).

- 4685 BCE: Likely date of construction of Mysinge 2 (Sweden) and Tulach an T`Sionnaich (Scotland).

- 4680 BCE: Likely date of construction of Point of Cott site (Scotland) and La Ciste de Cous site (France).

- 4680 BCE: Likely date of construction of Townleyhall II site (Ireland).

- 4675 BCE: Likely date of construction of Ardcrony (Ireland)

- 4671 BCE: Likely date of construction of Nutbane site (Ireland).

- 4670 BCE: Likely date of construction of Sobreira de Cima 3 site (Portugal).

- 4665 BCE: Likely date of construction of The Ord North site (Scotland).

- 4660 BCE: Likely date of construction of Vroue Hede and Holtenes III sites (Denmark).

- 4653 BCE: Likely date of construction of Warburg III site (Germany).

- 4650 BCE: Likely date of construction of North Mains site (Scotland), Huerta Montero (Spain), Phoenix Park (Ireland), Bagnolet (France), Cabeço da Areira, Cova de la Font del Molinot and Rabuje 5 sites (Spain).

- 4649 BCE: Likely date of construction of Stoneyfield, Raigmore site (Scotland)

- 4640 BCE: Likely date of construction of Tofta 14/Ansarve Hage (Sweden), Pena Guerra II (Spain), Hejring site (Denmark) and Ansião and Ta´Hagrat sites (Portugal).

- 4630 BCE: Likely date of construction of Odoorn site (Netherlands)

- 4620 BCE: Likely date of construction of Château Blanc site (France) and Giants Hills site (England).

- 4620 BCE: Likely date of construction of Hvalshøje site (Denmark)

- 4610 BCE: Likely date of construction of Quanterness site (Scotland) and L´Hotel de Dieu (France).

- 4605 BCE: Likely date of construction of Calden site (Germany).

- 4600 BCE: Likely date of construction of Warburg V site (Germany).

- 4590 BCE: Likely date of construction of Pedras Grandes and Snibhøj sites (Denmark) and Abogalheira 1 and Odoorn D32 sites (Netherlands)

- 4585 BCE: Likely date of construction of Lisduggan North (Ireland) and Mané Kernaplaye site (France).

- 4580 BCE: Likely date of construction of Fjälkinge 9 site (Sweden).

- 4570 BCE: Likely date of construction of Warburg IV site (Germany), Kinneved 21/Slutarp (Sweden) and Ditfurt, Vroue Hede Ia sites (Germany).

- 4560 BCE: Likely date of construction of Vroue Hede III (Denmark) and Falköpings västra 7 site (Sweden) Skjeberg (Norway).

- 4550 BCE: Likely date of construction of Dolmen de Viera site (Spain), Klokkehøj site (Denmark), Poulawack site (Ireland), Großeibstadt I, La Pierre Godon, Beaulieu and Odoorn D32a sites (Germany)

- 4545 BCE: Likely date of construction of Dötlingen site (Germany).

- 4540 BCE: Likely date of construction of La Chaussée Tirancourt (France), Odagsen and Ramshög sites (Germany) and Raevehøj (Denmark).

- 4535 BCE: Likely date of construction of Newgrange (Ireland) and La Grosse Motte (France).

- 4530 BCE: Likely date of construction of Sobreira de Cima 1 (Portugal).

- 4525 BCE: Likely date of construction of Castro Marim (Portugal).

- 4520 BCE: Likely date of construction of Rego da Murta 1 (Portugal), Nordhausen 2 and Dolmen de Mailleton sites (France), Sobreira de Cima 4 (Portugal).

- 4515 BCE: Likely date of construction of Karleby 59 site (Sweden).

- 4510 BCE: Likely date of construction of Hunnebostrand site (Sweden).

- 4505 BCE: Likely date of construction of Les Varennes (France) and Falköpings stad 3 site (Sweden).

- 4500 BCE: Likely date of construction of Noisy-sur-Ecole (France) and Tossen-Keler, Altendorf, Jörlanda 120, and Trekoner and Aguels sites (Spain).

- 4496 BCE: Likely date of construction of S. Caterina di Pittinuri site (Italy).

- 4490 BCE: Likely date of construction of Jordehøj (Denmark), Maison Rouge site (France) and Alvastra and Kellerød sites (Sweden).

- 4485 BCE: Likely date of construction of Tarxien site (Maltese Archipelago)

- 4485 BCE: Likely date of construction of Großenrode I site (Germany).

- 4480 BCE: Likely date of construction of Isbister (Scotland) and Cova de las Encantades de Martis (Spain) and Loon D15 and Horta (Netherlands).

- 4476 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cannas di Sotto site (Italy)

- 4475 BCE: Likely date of construction of Schönstedt site (Germany) and Ubby Dysselod (Denmark).

- 4470 BCE: Likely date of construction of Valle de las Higueras (Spain) and Gavrinis site (France).

- 4460 BCE: Likely date of construction of Berry-au-Bac and Niederbösa sites (Germany).

- 4450 BCE: Likely date of construction of Liscuis II site (France), Atteln (Germany), and Trigache 4, Cuesta de los Almendrillos and Cova del Frare sites (Spain).

- 4445 BCE: Likely date of construction of Kurtzebide site (Spain) and Schönstedt site (Germany).

- 4440 BCE: Likely date of construction of Maglehøj site (Denmark)

- 4435 BCE: Likely date of construction of Portejoie/sepulture 1 (France) and Kruckow (Germany)

- 4430 BCE: Likely date of construction of Goërem (France), Holm of Papa Westray North (Scotland) and Gökhem 78 and Valtorp 1 sites (Sweden)

- 4428 BCE: Likely date of construction of Falk stad 3 (Sweden).

- 4425 BCE: Likely date of construction of Stones of Steness (Scotland) and Ȧ Djèyî (France).

- 4420 BCE: Likely date of construction of Los Millares (Spain), Aldersro (Denmark), Monte Canelas 1 (Portugal), Saint-Gervais (France), Can Pey site (Spain), Øm site (Denmark), and Knowth 9 site (Ireland)

- 4410 BCE: Likely date of construction of Praia das Maças (Portugal), Santa Margarida 2 (Portugal), Casullo (Italy), Lairg, Achany Glen (Scotland), Arruda (Portugal).

- 4405 BCE: Likely date of construction of Buchow-Karpzow site (Germany).

- 4399 BCE: Likely date of construction of Knowth 16 site (Ireland)

- 4395 BCE: Likely date of construction of Annaghmare site (Ireland)

- 4390 BCE: Likely date of construction of Petit-Chasseur I (Switzerland) and Kermené (France).

- 4390 BCE: Likely date of construction of Cotogrande 5 site (Spain) and Falköpings stad 28 (Sweden).

- 4389 BCE: Likely date of construction of Lohra site (Germany).

- 4376 BCE: Likely date of construction of Warburg I site (Germany).

- 4375 BCE: Likely date of construction of Megalithe du Chateau site (France).

- 4370 BCE: Likely date of construction of Gökhem 31 (Sweden) and Hotié de Viviane site (France).

- 4360 BCE: Likely date of construction of Bola da Cera site (Portugal).

- 4340 BCE: Likely date of construction of Em

(The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Challenging the Migration Myth: Einkorn Wheat, Ancient Mariners, and the True Timeline of Megalithic Europe

For decades, the narrative of early farming in Europe has been dominated by the “migration model,” which suggests that agriculture spread westward through the gradual movement of farming communities from the Middle East. However, groundbreaking discoveries, including those at Bouldnor Cliff, the world’s oldest boatyard in Wales, and a comprehensive analysis of radiocarbon dates, are forcing a reevaluation of this long-held theory . These findings reveal a far more complex picture of prehistoric Europe, where sophisticated maritime trade networks predated and possibly facilitated the spread of agriculture, and where megalithic monuments were built millennia earlier than previously believed. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

The Einkorn Wheat Revelation at Bouldnor Cliff

Over a decade ago, archaeologists unearthed traces of domesticated einkorn wheat at an underwater site off the British coast at Bouldnor Cliff [1]. This discovery, dating back over 8,000 years, is significant because it predates the accepted timeline of farming in Britain by 2,000 years . The presence of einkorn wheat, a crop originating in the Middle East, challenges the notion that agriculture spread slowly and linearly across Europe through migration . Instead, it indicates that Mesolithic hunter-gatherers in Britain had access to agricultural products through complex trade networks stretching as far as the Middle East. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

This discovery implies that prehistoric societies possessed advanced seafaring capabilities, enabling long-distance exchanges thousands of years earlier than previously thought. The site at Bouldnor Cliff also yielded remnants of planked wooden boats, contradicting the traditional portrayal of these societies as primitive hunter-gatherers using only dugout canoes. These boats were capable of long voyages, facilitating trade routes that spanned vast distances . This evidence suggests a need to reconsider the conventional view of “hunter-gatherer” societies, acknowledging their skills as both traders and innovators in maritime engineering. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

The Oldest Boatyard: Catamarans and Maritime Mastery

Further bolstering the argument for advanced prehistoric maritime capabilities is the discovery of what has been called the “Oldest Boat Yard in the World” in Wales. Initially, archaeologists interpreted channels at the site as evidence of dugout canoe construction dating back 4,000 years. However, a more critical analysis, aided by LiDAR mapping and BGS data, revealed that these channels were part of a slipway for catamarans, not canoes. This is a crucial distinction, as the use of catamarans with outriggers is a remarkable engineering feat not recognized in the Western world until the 16th century. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

The boatyard’s slipway is associated with the transport of large stones. This suggests that these vessels were designed for moving heavy materials over water. The site’s dating has been revised to the Mesolithic period, around 8,000 BCE when it is believed that bluestones were transported to Stonehenge Phase 1. This dating aligns with the presence of Mesolithic tools found at the site. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

These findings at the boatyard further demonstrate the technological sophistication of prehistoric societies. Instead of simple dugout canoes, they were using complex vessels designed for long-distance travel and the transport of heavy loads . This undermines the idea of a slow and linear progression of technology and civilization, suggesting instead a more nuanced path with peaks and troughs of invention. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Radiocarbon Dating and the True Timeline of Megaliths

The traditional narrative of megalithic construction in Europe is also under scrutiny thanks to a comprehensive study that analyzed over 2,410 radiocarbon dates. This study, which employed Bayesian statistical modeling, concluded that megalithic construction originated in northwestern France around 4500 BCE and spread primarily through maritime networks. The study emphasizes the importance of coastal communities as key nodes in this cultural transmission, highlighting the advanced navigational and organizational skills of prehistoric Europeans. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

However, the study’s reliance on Bayesian analysis has faced critique for its inability to accurately identify original construction dates . Bayesian mathematics tends to average dates, which can skew results toward the midpoint and obscure the actual timeline of a site’s origin, particularly when dates span millennia. Reconstructing the radiocarbon data to focus on the earliest securely dated contexts, reveals that Carnac in France, not Stonehenge, is the oldest megalithic complex, dating to approximately 4500 BCE . (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

This revised data indicates that Stonehenge and other similar structures formed part of a network of early monuments reflecting regional variations and migrations of prehistoric cultures. This revised dating places construction thousands of years earlier than what has been previously presented. Mesolithic hearths at the bluestone quarries, Stonehenge’s old car park, and even beneath Stone 10 in the center circle consistently point to an 8300 BCE construction date. This challenges the traditional narrative that dates megalithic monuments to 5000 years later. The statistical probability of these dates aligning with Mesolithic features by chance is exceedingly low, supporting the idea of a Mesolithic origin for Stonehenge .

Implications for Prehistoric Migration and Trade

The implications of these findings are profound. The einkorn wheat discovery, the oldest boatyard, and the revised dating of megalithic sites collectively dismantle the “migration model” as the sole explanation for the spread of agriculture and culture in prehistoric Europe. Instead, the evidence suggests:

- Sophisticated Maritime Trade: Prehistoric societies were not isolated, but rather engaged in extensive maritime trade networks that facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies across vast distances.

- Advanced Seafaring Capabilities: The use of planked boats and catamarans demonstrates a high level of maritime skill and technology, enabling long voyages.

- Pre-Agricultural Networks: Trade routes likely predated the spread of farming, with the movement of people emerging as a byproduct of established trading activities.

- Mesolithic Origins of Megaliths: Megalithic monuments such as Stonehenge and Carnac were built thousands of years earlier than previously believed during the Mesolithic period’

These findings also challenge the notion of a linear progression of culture and technology. The existence of catamarans and complex trade networks in the Mesolithic period shows that societies were capable of advanced innovation and development much earlier than previously thought. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Reevaluating the Narrative

The persistent adherence to the outdated “migration model” has led to the misinterpretation and dismissal of crucial evidence . For example, discoveries at the Craig Rhos-y-Felin quarries, where bluestones for Stonehenge were sourced, reveal Mesolithic carbon dates that suggest a much earlier period of human activity than the Neolithic dates that were emphasized in reports Similarly, Mesolithic post holes discovered at the old car park at Stonehenge were dismissed as totem poles from unrelated hunter-gatherers, rather than being recognized as potential evidence of early activity at the site.

These examples underscore a reluctance within some archaeological circles to reconsider established narratives, even when faced with contradictory data. This highlights the need for more open and unbiased research approaches that prioritize the accurate interpretation of our past . As more evidence emerges, it becomes clear that the traditional academic framework for understanding early farming and trade in Europe is inadequate. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

The Need for a Paradigm Shift

The einkorn wheat discovery at Bouldnor Cliff, the oldest boatyard in Wales, the revised dating of megalithic sites, and the evidence of sophisticated maritime trade collectively call for a paradigm shift in archaeological thought . It’s time to move beyond the simplistic “migration model” and embrace a more nuanced understanding of prehistoric societies that recognizes their ingenuity, interconnectedness, and advanced technological capabilities. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

By embracing these new perspectives, we can:

- Acknowledge the complexity of prehistoric societies: Recognize that societies were not solely defined by their subsistence strategies (hunter-gatherer vs. farmer), but were capable of innovation and complex social and economic interactions.

- Reconsider the role of maritime activity: Acknowledge the crucial role of seafaring in the transmission of goods, ideas, and technologies throughout prehistoric Europe.

- Embrace new dating methods: Be cautious about relying on Bayesian statistical modeling, and incorporate alternative methods for determining construction dates and timelines.

- Promote open-mindedness in archaeological research: Encourage a more thorough and unbiased approach to data interpretation, where findings are not dismissed simply because they contradict established narratives.

In conclusion, the discoveries at Bouldnor Cliff, the oldest boatyard, and the radiocarbon dating of megaliths are not isolated anomalies. Instead, they form part of a larger pattern of evidence that challenges our understanding of prehistoric Europe and the “migration model” that has been used to explain the diffusion of agriculture and cultural practices’ This new evidence reveals sophisticated maritime trade networks, advanced seafaring capabilities, and the Mesolithic origins of monumental architecture, demonstrating the need for a more nuanced and accurate understanding of our shared history.

The evidence provided strongly supports the hypothesis that the site at Stonehenge was constructed at the same time as Carnac in France in the 9th millennium BCE. This places the construction of these sites thousands of years before the arrival of farming communities in Britain, demonstrating a more complex history and interconnectedness of European sites, and reinforces the evidence that the current hypothesis on migrations is wrong. This also strongly supports the idea that these sites were built by seafarers rather than farmers who moved across Europe. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

(The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

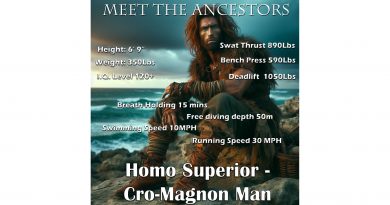

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives. (The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

(The Great Farming Hoax – Einkorn Wheat)

Pingback: SIX YEARS AGO, one of the greatest mysteries in archaeology was discovered - which has still to be resolved -