The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

Contents

Conundrum 12 – The Slaughter Stone……………………… Book Extract (The Great Stonehenge Hoax)

“The Killing of great numbers of human beings”

The Problem

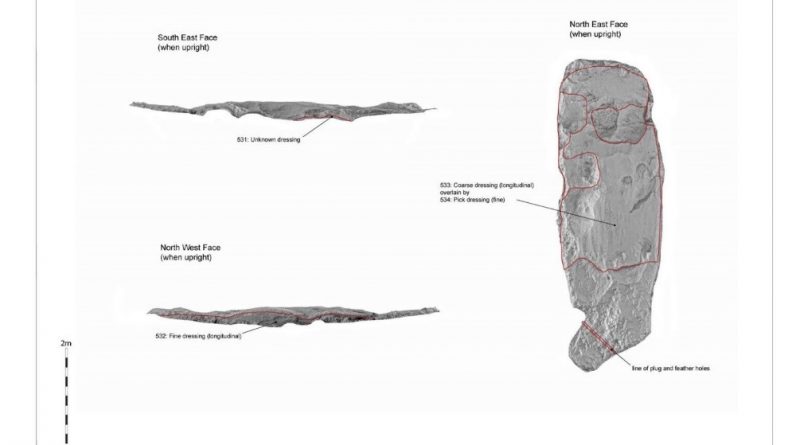

The slaughter stone has always been associated with mythology and speculation. Some say it was where Druids sacrificed bodies to their gods (hence the name); others suggested that it is merely a fallen Sarsen stone that once stood upright as the entrance to the monument. But recent scanning has shown that it was once sculpted to look ’lumpy and ‘rolling’,’ but why?

The Solution

In the centre of the Sarsen circle lays an extraordinary stone – the Altar stone; the reason it’s unique is two-fold. Firstly, it’s made of a material called mica, unlike the other Sarsen standing stones. ‘Hawkins notes that while all the other stones were either bluestone or Sarsen, the so-called altar-stone is ‘of fine-grained pale green sandstone, containing so many flakes of mica that its surface, wherever, wherever it is freshly exposed, shows the typical mica glitter’. The second reason is that it was positioned to be ‘flat’ to the landscape; the only other stone that was designed in that fashion is the Slaughter Stone.

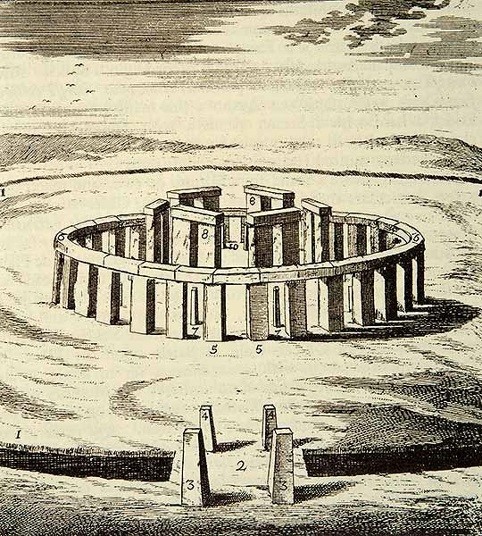

Most archaeologists believe that the Slaughter Stone was once a standing stone at the monument’s entrance; this is a flawed theory resulting from a hypothetical drawing by Inigo Jones in 1655. This drawing shows Stonehenge as a perfect circle (Roman Solar Temple) with a hexagon-shaped trilithon and three entrances into the site with six upright standing stones as access points, of which the slaughter stone was one. This idea was incorporated in John Aubrey’s drawing in 1666, which was more accurate, but again tended to place all the fallen stones in upright positions.

This false assumption was further compounded by William Cunning in 1880 when (it was reported) that he suggested his grandfather “saw” the upright slaughter stone in the 17th Century). This mistake was later corrected, yet the myths among archaeologists remain (Stones of Slaughter, E Herbert Stone, 1924, pp120). (The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone)

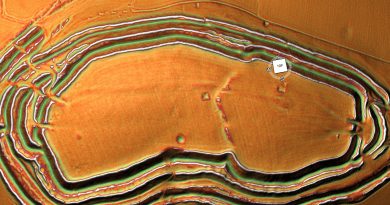

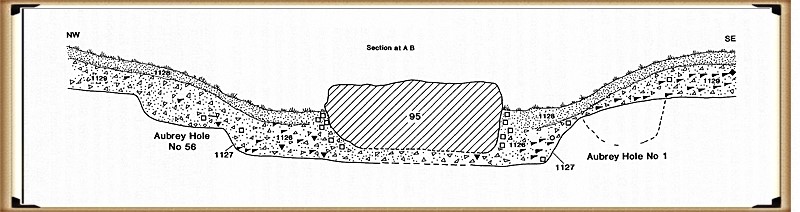

The reality is that the slaughter stone was always (like the Altar Stone) a deliberate recumbent, as the excavations of this stone by Hawley and Newall in the 1920s clearly show, as the chalk subsoil was also deliberately flattened before it was placed in its current position. Hawley presumed that the Slaughter Stone was once ‘buried’; this idea is understandable as the stone does lay below the ground level, but what Hawley never understood is that the reason the stone was in this position was for the same reason the ditch was built around Stonehenge, as it was made to be full of water.

This can be observed by the size of the stone hole called ‘E’ (WA1165), which lies two metres North West of the Slaughter stone but still within the ‘hollow’ that contains the stone. Most stone holes at Stonehenge are relatively shallow – less than a metre in-depth, but stone hole ‘E’ is twice as deep, over 2m. So if the Slaughter stone were placed in it (as the experts have suggested), it would only be 3m high on the surface, compared to 4.57m for the Heel Stone a few yards away.

The only other place in Stonehenge with these more massive pits is within the Ditch section surrounding the site, which is the same depth allowing access to the groundwater levels. In the past, when the Slaughter stone was placed in this ditch, like the moat, water would have surrounded the stone like an island.

Therefore, what we see today at Stonehenge is a 6,000 year-old relief map of the land the megalithic builders originated from – Doggerland, which now lays below the North Sea.

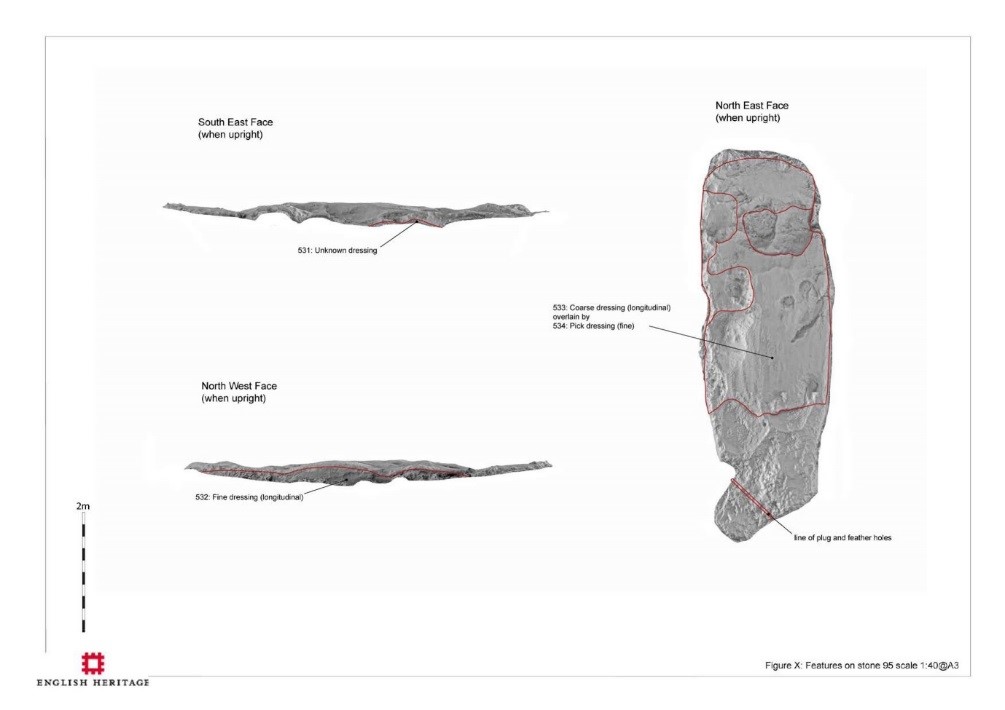

Not only did they place a 6ft piece of Sarsen stone, flat in a watery ditch, but they also carved out the island’s contours, showing high and low ground, like a contour relief map. Archaeologists have always believed these features were ‘weather-worn’ by age (although the other recumbent stones have not been weathered in the same fashion), but recent laser technology has confirmed our belief that this stone was carved, as the markings from the tools used, can still be seen at microscopic levels.

Moreover, and more importantly, the stone has been placed in a bizarre position, almost in the way of The Avenue. This shows that this stone and the Avenue have a connection, this type of relationship we see in association with Egyptian Pyramids when ‘sight lines’ are cut into the sides of the burial chambers to important star constellations to show their associations with the Gods.

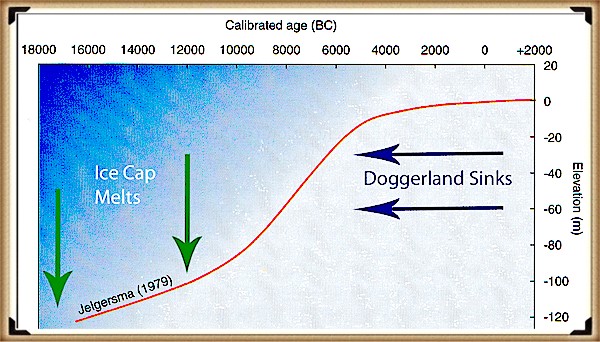

At Stonehenge, the Slaughter Stone and the Avenue are important as they link death with rebirth for this Megalithic Civilisation, for if we look from the Altar stone and follow a line past the Slaughter stone, they make a sight-line, which quite remarkably points directly to their homeland Doggerland. This was only a small island at the time of the Avenues construction in 4100 BCE but was constantly shrinking as the sea levels were (as now) continually rising. Geologists currently estimate the sinking of Doggerland as two thousand years earlier at 6200 BCE, as they have found a Tsunami that would have hit the island at that point in history.

Moreover, as we have seen in the Indian ocean and Japan – when tsunami’s hit, they do NOT sink the region, sadly, this is just another example of ‘bad science’ within archaeology. We can confirm that Doggerland did not disappear at this stage of history with a bit of simple maths. We know that the island is between 15m – 36m (average 25m) (Wikipedia) under the sea as a sandbank (and hence covered in modern-day wind farms). And we know (from satellites) that the sea rises 3.6mm per annum – consequently, by 4100 BCE it was still 6m above sea level, but probably so small it was uninhabitable.

2024 Update

The Altar Stone: A Shift in Understanding

When I first published my hypothesis in 2008 suggesting that the Altar Stone at Stonehenge might have originated from outside the commonly accepted areas—Avebury or the Preseli Hills—it was met with scepticism and outright ridicule. At the time, the consensus among archaeologists was that the stones were either quarried locally near Avebury or transported from Wales. Any suggestion that some stones, particularly the Altar Stone, could have come from farther afield was dismissed as pseudoscience. The reluctance to entertain alternative theories was emblematic of a broader resistance within the discipline to consider new ideas without substantial evidence.

Fast forward to today, and the story has taken a remarkable turn. Advances in geochemical analysis and improved scientific methods have provided new insights into the origin of Stonehenge’s stones, particularly the Altar Stone. Researchers have determined that this unique stone, composed of fine-grained pale green sandstone with a high mica content, does not match the geology of Wales or Cornwall, as once thought. Instead, studies now strongly suggest that it originated in Scotland, a revelation that challenges long-held assumptions and lends credibility to my earlier hypothesis.

The Altar Stone has always been an outlier in terms of its composition. Unlike the bluestones of Preseli or the massive Sarsens from the Marlborough Downs, its distinctive mica-rich material immediately set it apart. Early examinations by archaeologists like Richard Atkinson noted these differences but lacked the tools to trace their exact origin. It wasn’t until recent years that advanced geochemical fingerprinting techniques were applied, allowing scientists to identify its likely provenance with greater accuracy.

One pivotal breakthrough came in 2016 when researchers conducted isotopic analysis on fragments of the Altar Stone. These tests revealed a chemical composition that closely matched sandstone formations found in southern Scotland. This discovery was groundbreaking, as it opened the door to a broader understanding of how far people in the Neolithic were willing to travel—or trade—to obtain materials for their monumental constructions.

In 2020, further studies refined this analysis, narrowing the possible source to the southern uplands of Scotland. However, the exact quarry site remains unknown. This uncertainty stems from a lack of comprehensive geological mapping of underwater sandstone formations along Scotland’s eastern coast. Some experts have speculated that the stone may have been transported via waterways, possibly from a submerged quarry site now lying beneath the North Sea.

This raises intriguing questions about the logistical capabilities of Neolithic societies. How did they transport such a massive stone across hundreds of miles? Did they rely on an extensive network of waterways and seafaring routes, or were the stones traded overland in a series of exchanges between communities? These questions remain unanswered, but they highlight the sophistication of the builders’ organizational and engineering skills.

The story of the Altar Stone also underscores the slow pace of archaeological research. Despite the clear potential for groundbreaking discoveries, investigations into the origins of the stone have been limited by funding constraints and the challenges of underwater archaeology. The sandstone formations off the east coast of Scotland, which could provide definitive answers, have yet to be explored in detail. Without such investigations, the hypothesis that the Altar Stone came from this region remains partially validated but not fully proven.

Interestingly, the Altar Stone’s unique material properties may have held symbolic significance for the builders of Stonehenge. The shimmering mica within the sandstone gives it a luminous quality when freshly exposed, which may have been interpreted as having a spiritual or ritualistic importance. Its placement at the centre of the Sarsen circle, lying flat rather than upright like the surrounding stones, further suggests it played a central role in the monument’s purpose.

The debate over the Altar Stone’s origin is part of a broader reevaluation of Stonehenge’s construction and function. The monument was interpreted primarily as a solar temple or astronomical observatory for centuries. However, newer theories emphasize its role as a site of cultural and ritual significance, with connections to far-flung regions of the Neolithic world. The diversity of the stones’ origins supports the idea that Stonehenge was not just a local project but a monument with broader regional and possibly even international connections.

This evolving understanding of the Altar Stone exemplifies the dynamic nature of archaeology. What was once dismissed as pseudoscience is now recognized as a plausible and even likely explanation. It also highlights the importance of revisiting old assumptions with new tools and technologies. Had geochemical fingerprinting not been applied, the Altar Stone’s Scottish origin might still be unknown.

The following steps in this journey will likely involve underwater archaeology, a field that has only recently begun to gain traction. As technology improves and funding becomes available, it is hoped that investigations into the submerged sandstone formations along Scotland’s coast will uncover the exact source of the Altar Stone. Such a discovery would not only validate this hypothesis but also shed light on the broader network of trade and communication that existed in Neolithic Britain.

Until then, the story of the Altar Stone remains a testament to the resilience of ideas and science’s slow but steady progress. It serves as a reminder that archaeology, while painstakingly slow, has the power to rewrite our understanding of history. My initial hypothesis, once dismissed, has found a place in the growing body of evidence that challenges traditional narratives about Stonehenge and its builders.

Unearth the Astonishing Secrets of Stonehenge (The Stonehenge Hoax)

Introduction

Video

Synopsys

Stonehenge, a timeless enigma etched in stone and earth, has stood as a formidable puzzle challenging the intellects of archaeologists and historians alike. Despite the myriad attempts, including books, TV programs, and academic conferences, the secrets of these ancient stones and their encircling ditches have proven elusive. Against this backdrop, we scrutinise the existing thirteen hypotheses, each presenting its narrative but collectively lacking a coherent thread.

In adopting the deductive reasoning akin to Sherlock Holmes, we endeavour to weave these disparate threads into a unified tapestry that not only unravels the mystery of Stonehenge but also shakes the foundations of established academic narratives. This intellectual journey may induce some discomfort as we challenge conventional perceptions and invite a reevaluation of our understanding of the past. Apologies are extended in advance for any cognitive dissonance, but the pursuit of truth and reason mandates an unfiltered presentation of the facts.

So, fasten your seatbelts for an expedition into the archaeological unknown.

As we navigate this intellectual rollercoaster, be prepared for a revelation that might reshape our understanding of Stonehenge and question the foundations of our historical narratives. The dawn of a new archaeological era awaits promising insights that could leave even the most curious minds astonished. As we delve into this intellectual rabbit hole, be ready for a revelation that could make Alice astonished.

Robert John Langdon (2023) – (The Stonehenge Hoax)

The Journey

Langdon’s journey was marked by meticulous mapping and years of research, culminating in a hypothesis that would reshape our understanding of prehistoric Britain. He proposed that much of the British Isles had once been submerged in the aftermath of the last ice age, with these ancient sites strategically positioned along the ancient shorelines. His groundbreaking maps offered a fresh perspective, suggesting that Avebury had functioned as a bustling trading hub for our ancient ancestors. This audacious theory challenged the prevailing notion that prehistoric societies were isolated and disconnected, instead highlighting their sophistication in trade and commerce.

In the realm of historical discovery, the audacious thinkers, the mavericks who dare to question established narratives, propel our understanding forward. Robert John Langdon is undeniably one of these thinkers. With a deep passion for history and an unyielding commitment to his research, he has unearthed a hidden chapter in the story of Avebury that transcends the boundaries of time and offers fresh insights into our shared human history.

As Langdon’s trilogy, ‘The Stonehenge Enigma,’ continues to explore these groundbreaking theories, it beckons us to embark on a journey of discovery, to challenge our assumptions, and to embrace the possibility that the past is far more complex and interconnected than we ever imagined. With its ancient stones and enigmatic avenues, Avebury continues to whisper its secrets to those who dare to listen, inviting us to see history through a new lens—one illuminated by the audacious vision of Robert John Langdon.

(The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes)

The Book

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today. (AI now Supports – Homo Superior)

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?