Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

Contents

Introduction

Could Antler Picks build these Monuments……………….. (Extract from the Book -The Great Stonehenge Hoax)

The Problem

The first time real science could be used to date the ancient monument was when archaeologists ‘carbon dated’ the antler picks found within the ditch of the site – as it was assumed that these were the tools used to dig the ditches, which they had been discarded as a ‘ritual’ to the bottom of the trench once it was completed. Since then, archaeologists have attempted to justify these dates with all new finds on the site and have rejected as anomalies all other radio carn dates that don’t match its ‘established’ timescale.

The Solution

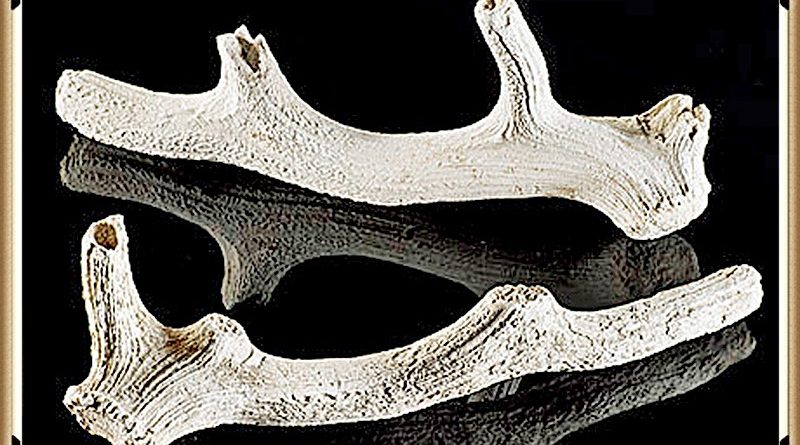

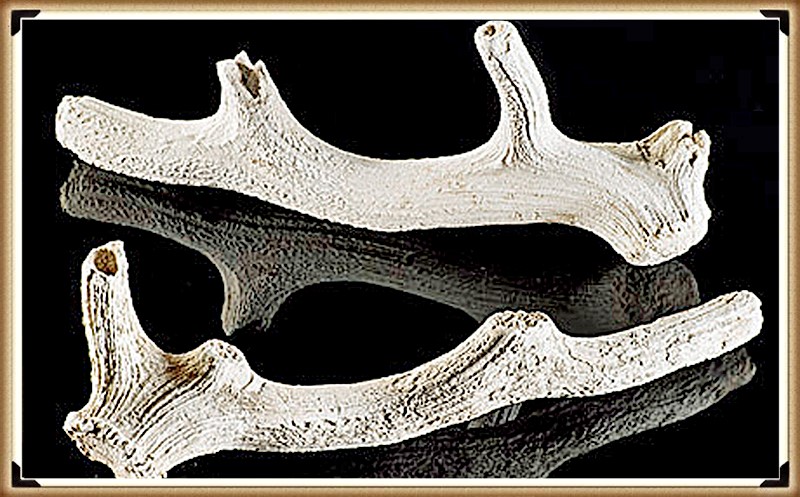

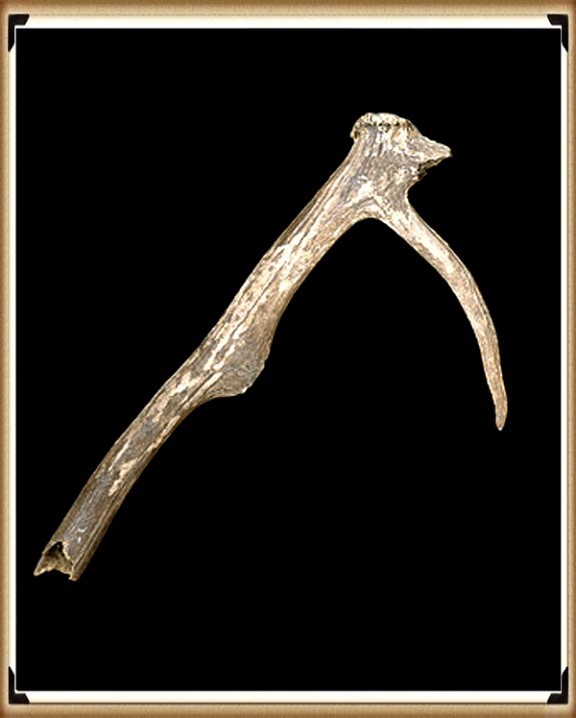

A type of tool found widely among the sites of Neolithic communities in North-Western Europe. They are formed from a red-deer antler from which all but the brow tine has been removed; the beam forms the handle, and the brow tine the ‘pick’. They were used for excavating soil and quarrying out stone and bedrock. The marks left by their use have been detected on the sides of ditches, pits, and shafts. Experiments suggest that they were used more like levers than the kind of pickaxe swung from over the shoulder. (Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology)

If you read any book or watch a program about archaeology and the construction of their monuments and sites, you will hear the experts talk about finding antler picks in the general vicinity and linking the structure with these objects. As the description above indicates, these ‘tools’ are from red deer, which shed these natural growths annually.

According to archaeologists, this was the primary tool of prehistoric people – a natural resource that became a handy tool in excavating the ditches and digging holes in the chalk bedrock that surrounded most of their sites. This is where the Victorian term ‘antler picks’ originates and still exists today, but for an unknown reason, this tool has now changed its use (but not its name), as archaeologists have now realised that if these ‘antlers’ were used to cut into hard bedrock chalk, they would leave blunt ends and scars from flint re-sharpening, which there is no evidence.

Yet, if you look at any prehistoric report about the monument’s construction, you find a degree of ‘acceptance’ that antlers were used as the primary source of digging out the chalk downlands. For example, here is a typical report from English Heritage’s ‘bible’ (Stonehenge in its landscape, 1995, Cleal et al.) and the use of Antler picks. (Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument)

“Over 130 antler implements are known to survive from excavations by Gowland, Hawley, and Atkinson et al. Antler implements have frequently been associated with Neolithic and Early Bronze Age monuments in Britain located on chalk or limestone, and it is generally assumed that they were the principal implements used in the digging of ditches, postholes and stone holes.

In a paper on the Neolithic, engineer Atkinson (1961) wrote, “the tools used – antler picks, bone wedges and occasionally stone axes – are well-known and require no further discussion. However, some of the generalisations made in the literature about antler implements require modification in the light of the finds from Stonehenge.”

The Victorian Archaeologists found antlers all over Stonehenge, particularly in the ditches that had filled up over the years. So, the conclusion ‘was that no other tools’ – apart from antlers and bone parts had been used as these were the only remains found. However, the only part of the antler that could successfully break the solid chalk is the harder ‘tines’. (Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument)

The problem with the tines is that they all grow the same way, and so they would not naturally allow a clean strike at the chalk bedrock if used like a ‘pickaxe’ unless you removed two of the three tines. And hence the ‘gobbledygook’ sorry line in the Atkinson’s report which says that “methods of modification and the forms of the picks are more varied than has been hitherto appreciated”.

If we are the seeing systematic use and preparation of these tools (as has been suggested by archaeologists in the past), we should first see two clean cuts with a stone axe or cutter to ‘prune’ the antler and then secondly blunt and reshaped tines with compression strikes from a stone or another blunted instrument on the antler stem behind the tine spike – but we don’t! (Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument)

Of the 118 antler picks found at Stonehenge, 82 antlers had the harder tines attached. Of the 82 with tines – only 25 had the other two smaller tines removed to make them usable; this is only 21% of the antler finds. Moreover, none of the 25 picks that could have been used had compression marks or signs of sharpening. (Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument)

Remembering, these 25 picks were the entire finds within the Stonehenge area, which archaeologists have suggested was constructed in three phases over 700 years.

Moreover, in Phase I of the Ditch, Bank and the construction of the Aubrey holes (which would have contained the Bluestones from Wales). It has been estimated that these tools needed to remove 87,000 cubic feet of chalk, taking 30,000 working hours. Yet, according to the location where the discarded antlers were found, only seven suitable antlers were available with the correct tines removed; this would mean that each whole antler had removed 12,429 cubic feet without damage.

Sadly, even more implausible, we have not even considered the size of the antler. The bigger, the better (more robust), and the more extended the antler, the better the levering motion and ability to remove the chalk blocks easily.

This being the case, they must have used the most massive antlers possible, especially considering the enormous number of Deer in Britain in prehistoric times compared to today. Furthermore, bucks shed their antlers annually; there are 1.5 million Red Deers in Britain – therefore, the builders of Stonehenge could have chosen the best from at least a million shed antlers.

However, the evidence shows that this was far from the truth. The distribution analysis shows that the sizes varied greatly with the number of antlers found. The average length of a typical antler found at Stonehenge is just 210mm (8.5″), and some antlers are as small as 150mm (6 inches) in size – compared to the most significant found, which was 299mm (12 inches) in length, and only one of this size was found. Antlers typically measure 710mm (28 in) in total length, although large ones can grow to 1150 mm (45 in). Consequently, they used the most inferior antlers available?

The statistics we have obtained from English Heritage ‘could be much better’ and more accurate as they only measure the distance between the bur (the thickest part attached to the head) and the trez, which is the third tine up from the base bur. The Trez is not the strongest tine on the antler – that is the brow. However, there are so few antlers cut to this correct and more effective way that EH decided on this unorthodox method to compare sizes – even so, we can see these antlers were not selected for their size. The Average size (distance from Bur to Trez) was 190mm (7.5″), some as small as 110mm (4″) – compared to the largest again available of 410mm (16″).

This strange lack of evidence can also be seen in other monuments where even greater numbers of ‘antler picks’ would be required – but have not been found. Such as Avebury, which has one of the most significant monuments in Britain containing three stone circles within. Current archaeological estimates suggest that it took 1.5 million working hours to build the Avebury monument, including digging out 3.4 million cubic feet of chalk, which is forty times larger than Stonehenge. (Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument)

Excavation at Avebury has been limited. In 1894, Sir Henry Meux put a trench through the bank, which gave the first indication that the earthwork was built in two phases. The site was surveyed and excavated intermittently between 1908 and 1922 by a team of workmen under the direction of Harold St George Gray. He could demonstrate that the Avebury builders had dug down 11 metres (36 ft) into the natural chalk using ‘red deer antlers’ as their primary digging tool, producing a henge ditch with a 9-metre (30 ft) high bank around its perimeter. Gray recorded the base of the ditch as being four metres (13 ft) wide and flat, but later archaeologists have questioned his use of untrained labour to excavate the ditch and suggested that its form may have been different. Gray found few artefacts in the ditch-fill, but he did recover scattered human bones, among which jawbones were particularly well represented. At a depth of about two metres (7 ft), Gray found the complete skeleton of a 1.5-metre (5 ft) tall woman. (Wikipedia)

Grey cut through the ditch and suggests the tools that built this structure, but the expected vast amounts of abandoned antler picks from their labour are minimal to non-existent. The reality is that he found more human bones than antlers. (Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument)

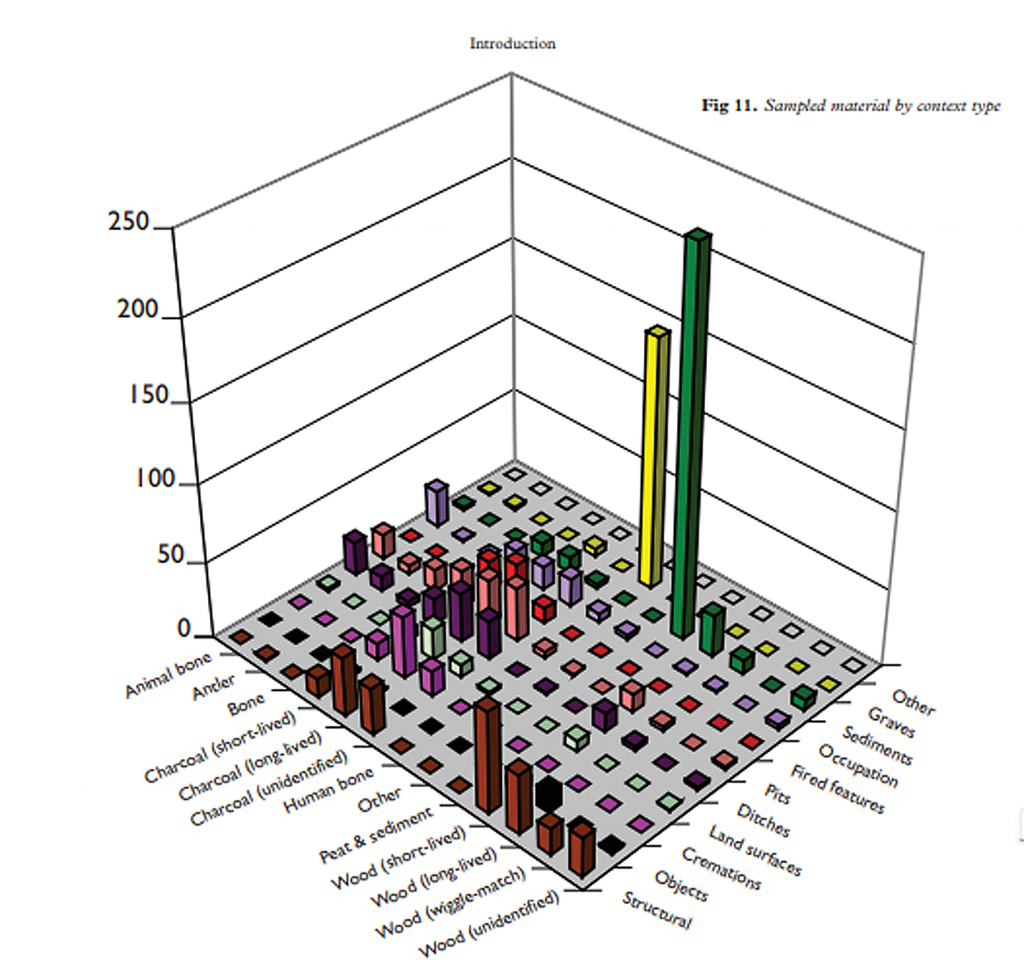

To highlight the absurdity of this antler myth, we need not look any further than English Heritage’s publication called ‘Radiocarbon Dates, from samples funded by English heritage from 1981 – 1988’ – one would imagine that if we scratch below the surface of these monuments, the broken remains of the tools used to build these magnificent constructions would be obvious. Instead, however, the book tells another story.

Of all the samples found, ‘Antler’ was the second smallest behind Animal Bone, Human Bone, Wood and Charcoal by a large margin. Animal Bones fragments were three times larger than antlers. However, human bones were five times the most significant find – the reality is they found only three pieces of antler (one from the bank of Avebury in 1937, one from West Kennet Avenue and one from the Avebury ditch in 1909), and even then, we are not sure what parts of the antler were found. (Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument)

Therefore, how can a scientific discipline claim that these features were made from antler picks and shoulder blade shovels when only one antler fragment was ever carbon-dated at Avebury?

The truth is that this myth has grown around the excavations in the last century at Stonehenge when the archaeologists found antler picks in the ditches. Carbon dating was a new science in the 1950s, and only organic samples could be dated – therefore, antler picks were perfect for testing out this unique dating process, and the site had just been ‘revamped’ by the ministry of works in 1958, to become a new tourist attraction – adding paths, concreting prehistoric sarsen stones and rehanging lintels. (Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument)

Therefore, a new date in the distant past was excellent news for the media, and consequently, the archaeological circus started and has never finished – with a constant need for publicity rather than sound science.

The reality is that rather than using antler picks to build these monuments, the workers used a much more resilient and more practical tool which we know does not break as often and was abundant at the time of the construction of these sites – the stone axe.

This is the ONLY tool that could have been used to cut down the trees for these monuments – yet they put it away to use an inefficient antler tool when digging out either pits or ditches? Such an idea is so absurd that it does question the expertise of those who continually suggest that the antler pick was used for such tasks and that the construction dates based on these tools are accurate.

Moreover, some have broken ranks in recent years and offered tantalising clues on a more rational explanation of our history and the deception game being played by academia Mike Parker-Pearson in his book ‘Stonehenge’ revealed that they found ‘cut marks’ in the chalk in an excavation at Durrington Walls (Woodhenge) that looked like it was made from a ‘metal’ instrument.

This would make a lot more sense than current archaeological theories – but what is the big deal if this was true. Why not accept the evidence and go forward with these more practical metal tools?

Well, this is when archaeology ‘digs’ itself into a giant theoretical hole as metals (such as Bronze) were supposedly not invented until AFTER 2500 BCE in Britain (hence the Victorian term of the ‘Bronze Age’ – 2500BCE to 70BCE), 800 years before the supposed build date of Stonehenge.

However, we now know that bronze and copper axes were available elsewhere in Central Europe and the Mediterranean thousands of years earlier. And it is pretty feasible that these tools were available as we now believe we have been trading with Europe since the Mesolithic period. As we have found boat yards (at the bottom of the Solent) that travelled to Anatolia for grain in the 6th Millennium BCE.

Unearth the Astonishing Secrets of Stonehenge (The Stonehenge Hoax)

Introduction

Video

Synopsys

Stonehenge, a timeless enigma etched in stone and earth, has stood as a formidable puzzle challenging the intellects of archaeologists and historians alike. Despite the myriad attempts, including books, TV programs, and academic conferences, the secrets of these ancient stones and their encircling ditches have proven elusive. Against this backdrop, we scrutinise the existing thirteen hypotheses, each presenting its narrative but collectively lacking a coherent thread.

In adopting the deductive reasoning akin to Sherlock Holmes, we endeavour to weave these disparate threads into a unified tapestry that not only unravels the mystery of Stonehenge but also shakes the foundations of established academic narratives. This intellectual journey may induce some discomfort as we challenge conventional perceptions and invite a reevaluation of our understanding of the past. Apologies are extended in advance for any cognitive dissonance, but the pursuit of truth and reason mandates an unfiltered presentation of the facts.

So, fasten your seatbelts for an expedition into the archaeological unknown.

As we navigate this intellectual rollercoaster, be prepared for a revelation that might reshape our understanding of Stonehenge and question the foundations of our historical narratives. The dawn of a new archaeological era awaits promising insights that could leave even the most curious minds astonished. As we delve into this intellectual rabbit hole, be ready for a revelation that could make Alice astonished.

Robert John Langdon (2023) – (The Stonehenge Hoax)

The Journey

Langdon’s journey was marked by meticulous mapping and years of research, culminating in a hypothesis that would reshape our understanding of prehistoric Britain. He proposed that much of the British Isles had once been submerged in the aftermath of the last ice age, with these ancient sites strategically positioned along the ancient shorelines. His groundbreaking maps offered a fresh perspective, suggesting that Avebury had functioned as a bustling trading hub for our ancient ancestors. This audacious theory challenged the prevailing notion that prehistoric societies were isolated and disconnected, instead highlighting their sophistication in trade and commerce.

In the realm of historical discovery, the audacious thinkers, the mavericks who dare to question established narratives, propel our understanding forward. Robert John Langdon is undeniably one of these thinkers. With a deep passion for history and an unyielding commitment to his research, he has unearthed a hidden chapter in the story of Avebury that transcends the boundaries of time and offers fresh insights into our shared human history.

As Langdon’s trilogy, ‘The Stonehenge Enigma,’ continues to explore these groundbreaking theories, it beckons us to embark on a journey of discovery, to challenge our assumptions, and to embrace the possibility that the past is far more complex and interconnected than we ever imagined. With its ancient stones and enigmatic avenues, Avebury continues to whisper its secrets to those who dare to listen, inviting us to see history through a new lens—one illuminated by the audacious vision of Robert John Langdon.

(The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes)

The Book

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?