The Stonehenge Avenue

The Stonehenge Avenue investigation transcript.

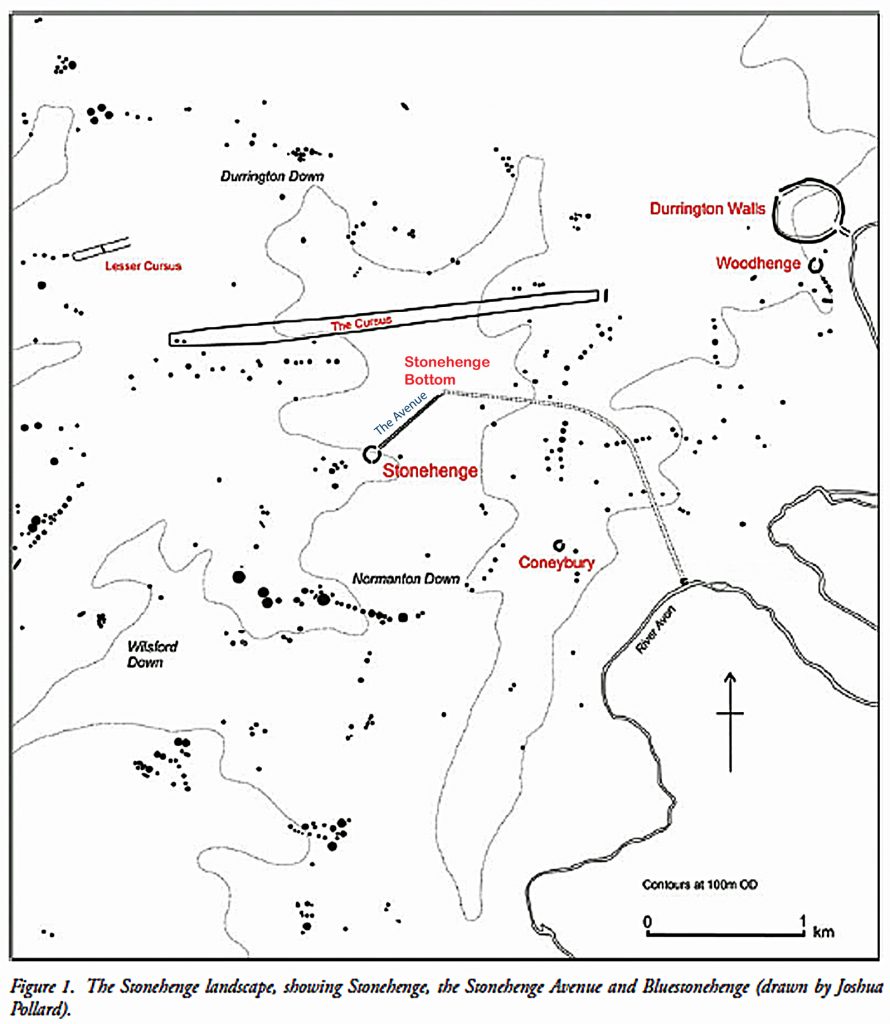

In our last video we looked at Stonehenge during the Mesolithic period and showed that the Dry River Valley (that surrounds the site) is called ‘Stonehenge Bottom’ and was full of water during this period, as the many natural springs in Stonehenge Bottom would have flooded the area, up to the Old Car Park. We believe this was the landing site where the four-tonne Bluestones that travelled by boat from their quarry site in Wales.

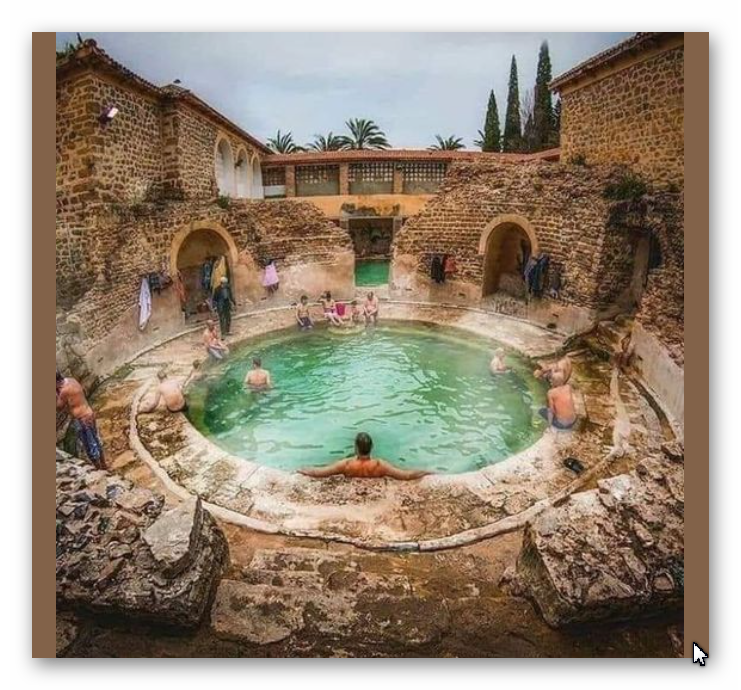

This was the start of Stonehenge (Phase I), which was a ditch surrounding the site, with 56 Bluestone chalk pits known as Aubrey Holes. This construction was used as a bathing place as the excavation is unique as it is not a traditional ditch, but a series of individual 2m deep chalk holes with walls and seats. This facility was used with the Bluestone chippings to heal ailments and diseases, as we see later in history with Roman baths.

This structure lasted for thousands of years and was replenished periodically with more Bluestones as they were chipped away from the large stone blocks until the Neolithic period when the site changed its function. This change was necessary as the water table in the area had dropped (and consequently, the shoreline of the River Avon within the Stonehenge Bottom). This drop in the water table dried up the ditch, and so it could no longer function as a bathing pool.

At this stage, a new monument was created to celebrate the Motherland of these ‘Megalithic Builders’ who originally came from Doggerland in the North Sea, which had surrendered to the rising sea levels (the original) global warming event. So, they decided to build a stone structure in remembrance, as we continue to do today for monumental occasions.

Moreover, the River Avon was now much lower than in the Mesolithic and to bringing the Bluestones to Stonehenge (from the quarry) became more difficult and so, to meet the retreating water, a new ‘pathway’ was constructed with mooring points throughout its length – this is called The Avenue.

Traditional archaeologists believe that the Avenue existed before the start of Stonehenge as a natural feature – excavations have revealed ‘preglacial stripes’ which they believe was the reason Stonehenge was placed in this low location. These Stripes (they imagine) were created through tundra thawing and freezing during the last ice age.

The problem with this idea is that these stripes were only found within this 20 ft wide narrow path going to the site and not over the general area as would be expected as the geology within this area of the Avenue is pretty universal (chalk bedrock) and not unique, so this idea can easily be dismissed.

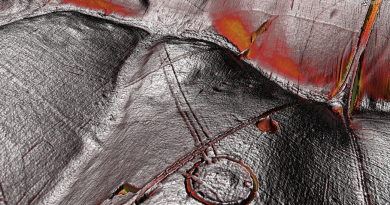

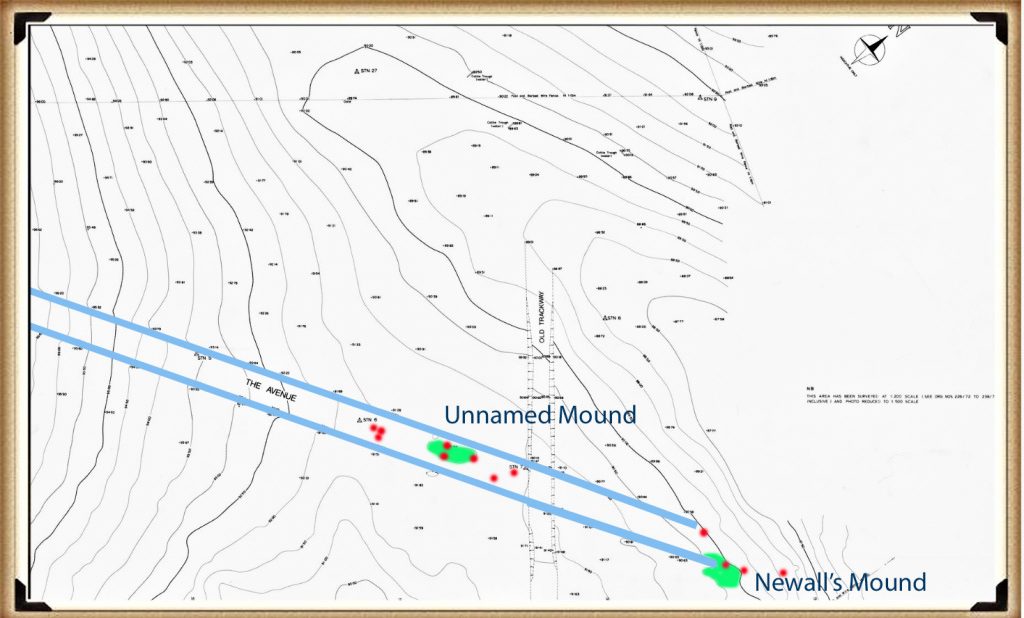

From the LiDAR scan, it is obvious (and we will change the colour to see the detail better), that it is a roadway with ditches on the edge. Inside it the excavations shows track marks of past visitors who used the Avenue as a natural road for their transportation, as seen in Stukeley 18th century drawings – we have found evidence from latter cart tracks in excavations, and these are pretty shallow as the carriages are only about 1500lbs to 1800lbs in weight (0.8 tonnes), but the deeper cuts are clearly from overly heavy wheeled vehicles used to ship the massive 25-tonne sarsen stones to the site during the Neolithic and hence their misidentification.

These archaeologists also support that the Avenue takes a ‘long walk’ down to the existing River Avon past a series of borrows on the opposite hill (called The Kings Barrows). This may be the case today, with a light path that some wander down as it appears on their OS maps, but the reality is that it didn’t exist in the past or on the first series of OS maps.

If we look at the End of the Avenue, we see that the river valley looks like it splits as we see in Stukeley’s 18th-century drawing – but compared to the deep cuttings of the original Avenue, they are not worth considering as original.

The larger Sarsen stones would have been transported from the bottom of the Avenue (as shown on the LiDAR Map) as this feature’s final function. Prior to that occasion, the Avenue would have been used over a couple of thousand years to bring the Bluestone in the Late Mesolithic and Early Neolithic, from their quarry site which can be seen from the post holes in the Avenue (which could not have any other useful function) these are at an angle to the shoreline, as we saw in the Old Car Park at Stonehenge.

We also see two artificial flint mounds within the Avenue (pic). One has been identified as Newmans Mound, and the other remains unidentified. These features have no other rational explanation other than unloading platforms for boats on the River Avon in the Neolithic.

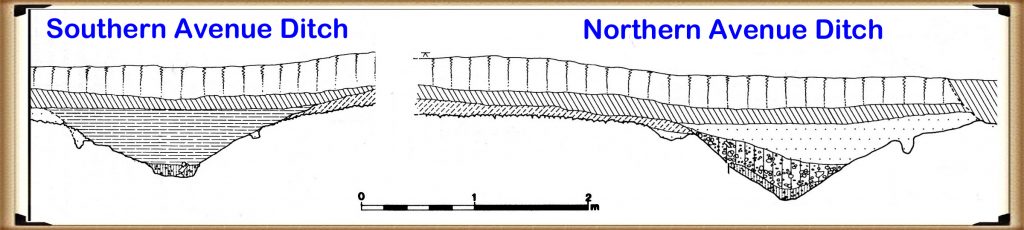

Moreover, the physical construction of the Avenue earthwork shows the incorporation of water features, supporting the higher water table theory. For example, the Southern ditch is much shallower than the Northern ditch of the Avenue. This is because the river lies on the Southern side of the Avenue and does not need extra depth to fill the Southern ditch evenly, while the Northern ditch is further away from the river.

Furthermore, this extra depth to one side of the monument can also be seen in the main ditch of Stonehenge as the north western side also 10% deeper, reflecting the water table at that time.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.