Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

Contents

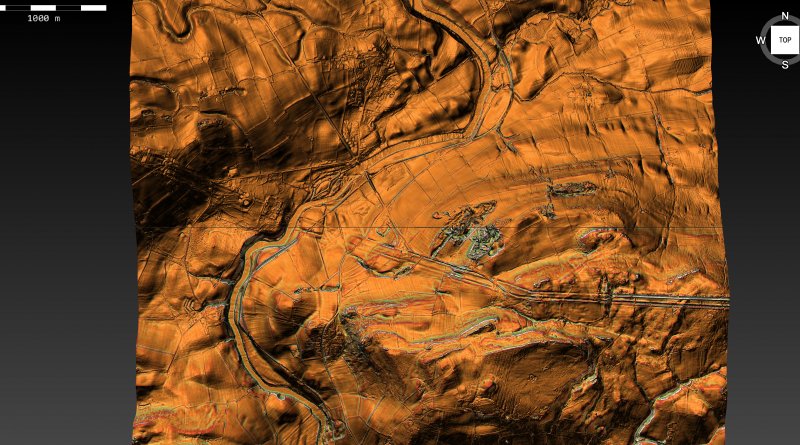

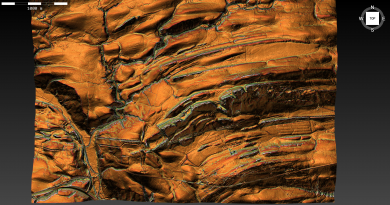

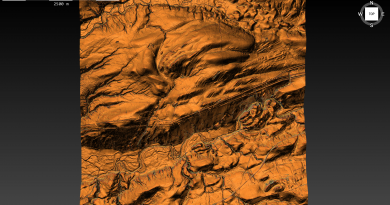

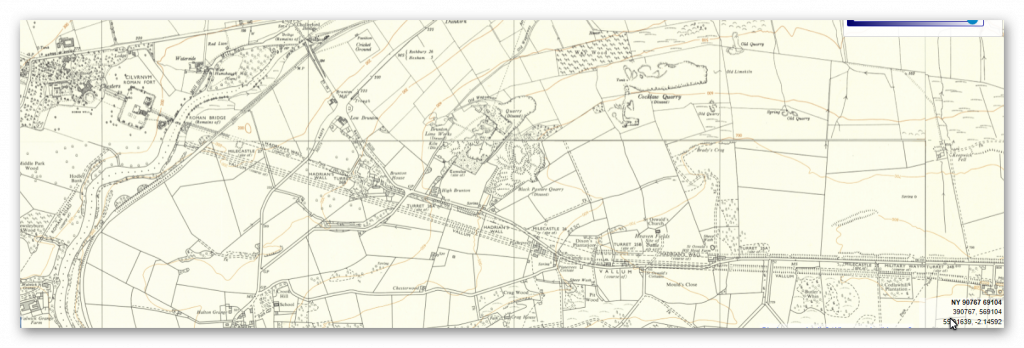

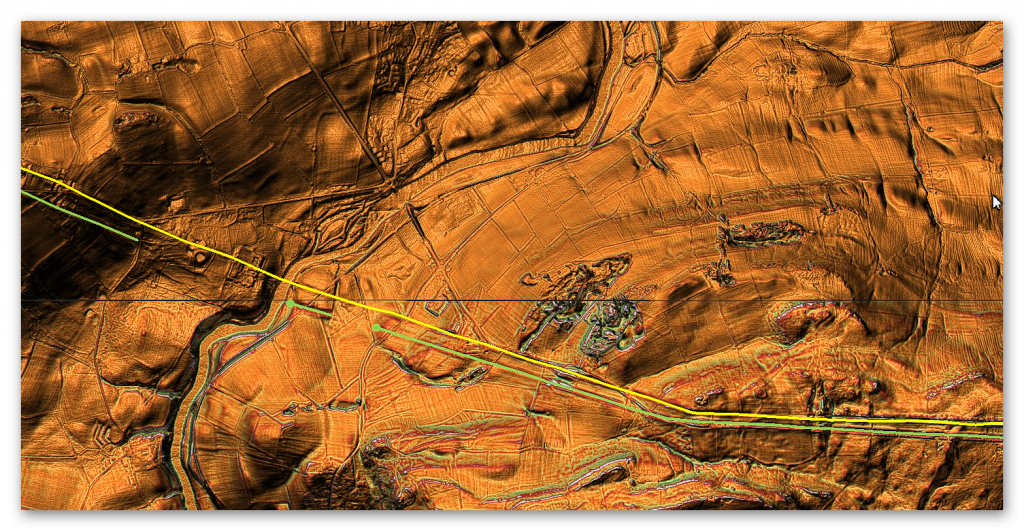

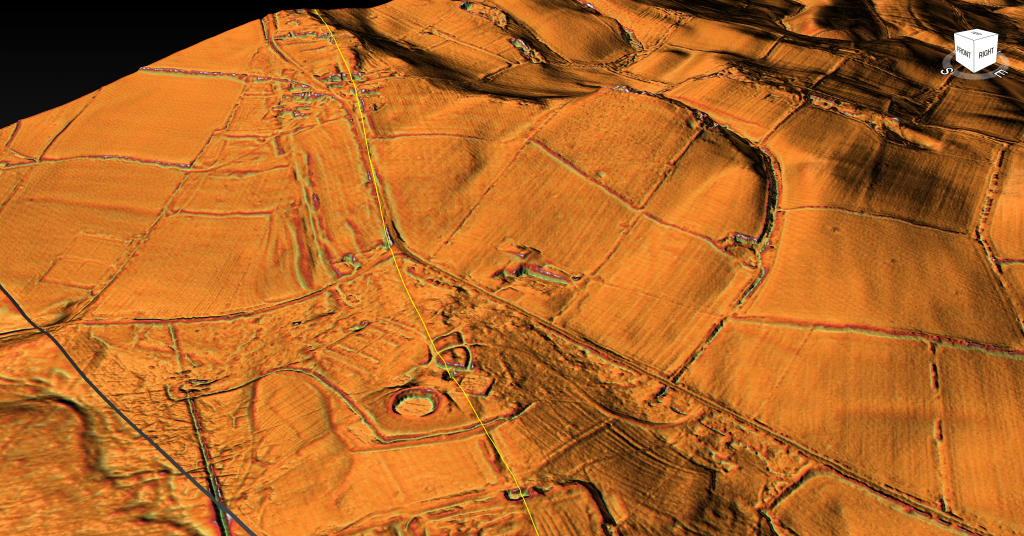

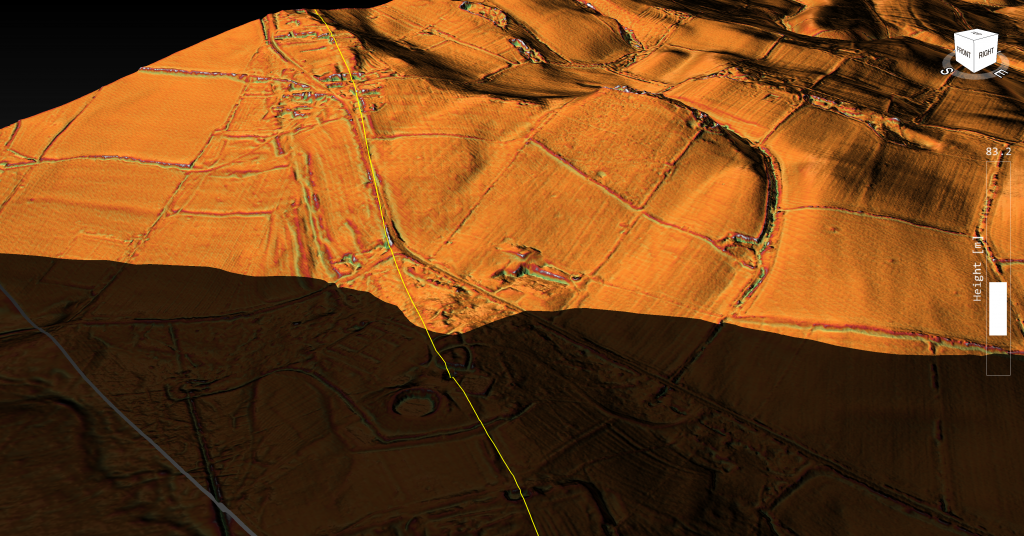

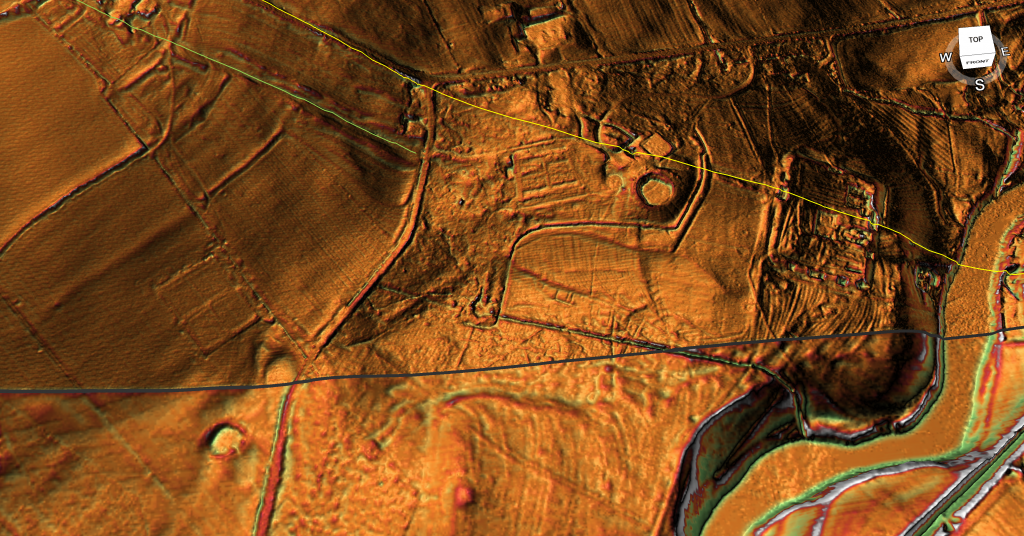

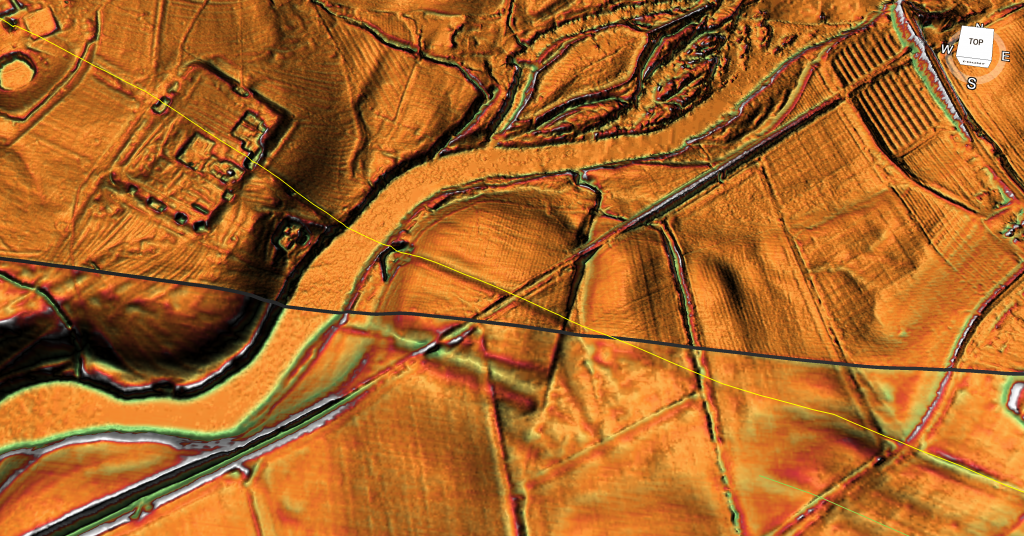

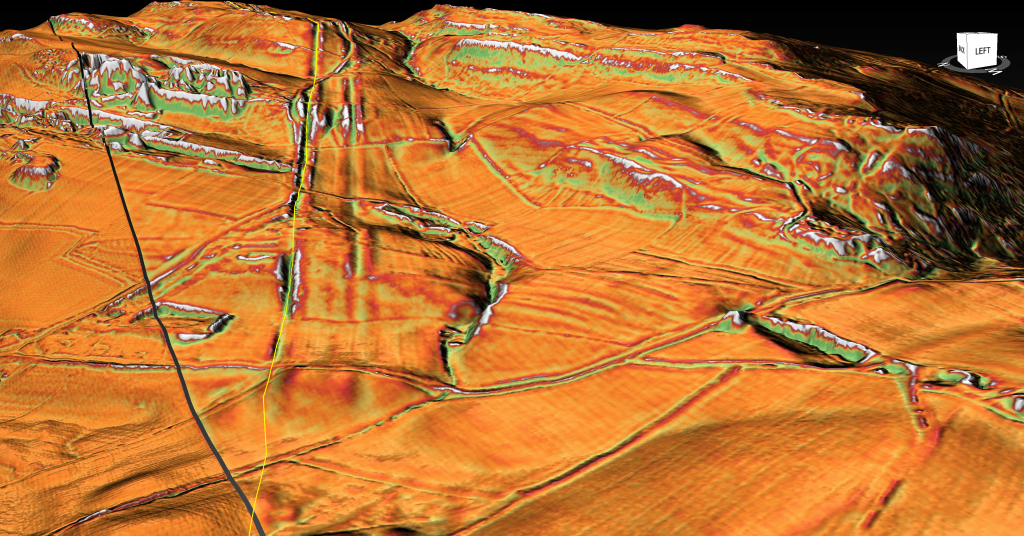

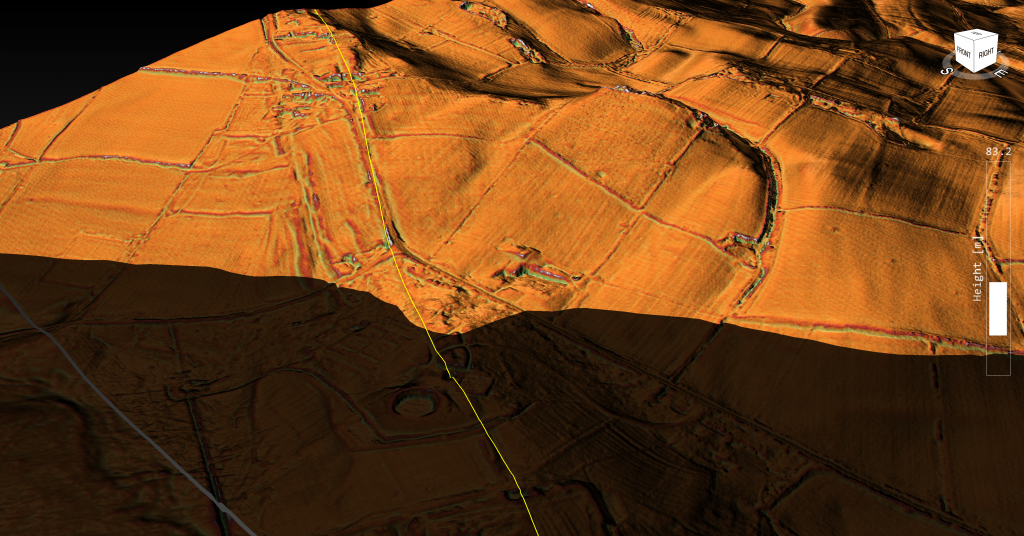

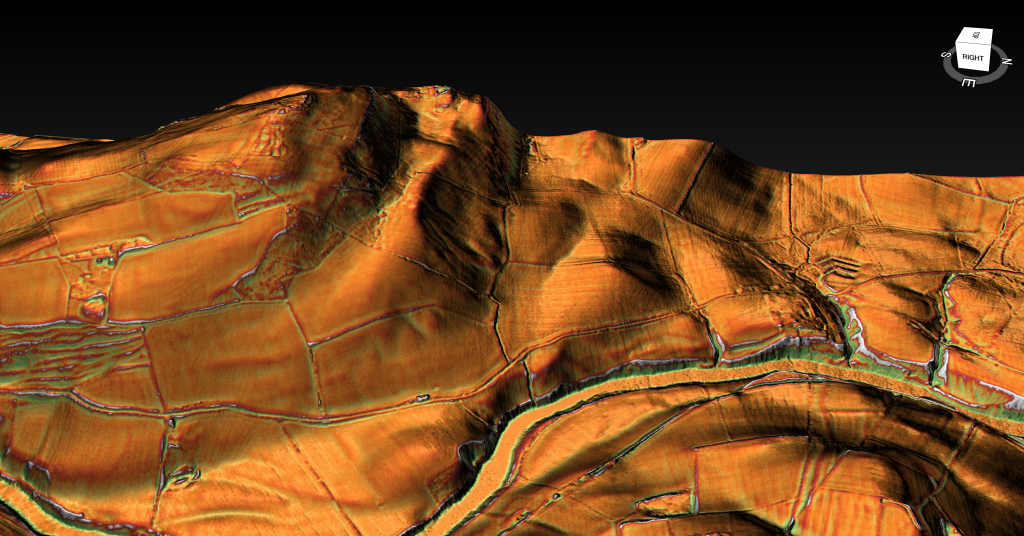

Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW – this is a section of Hadrian’s Wall showing the LiDAR, Google Earth and 1800 Maps of the Area covered by Historic England

Historic England Sections:

Name: Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between field boundary east of milecastle 24 and the Roman fort, vicus, bridge abutments and associated remains in wall miles 24, 25, 26 and 27

List UID: 1010958, 1010959, 1018581

Old OS Map

LiDAR Map

Google Earth Map

Historic England Scheduled Monuments within Section O

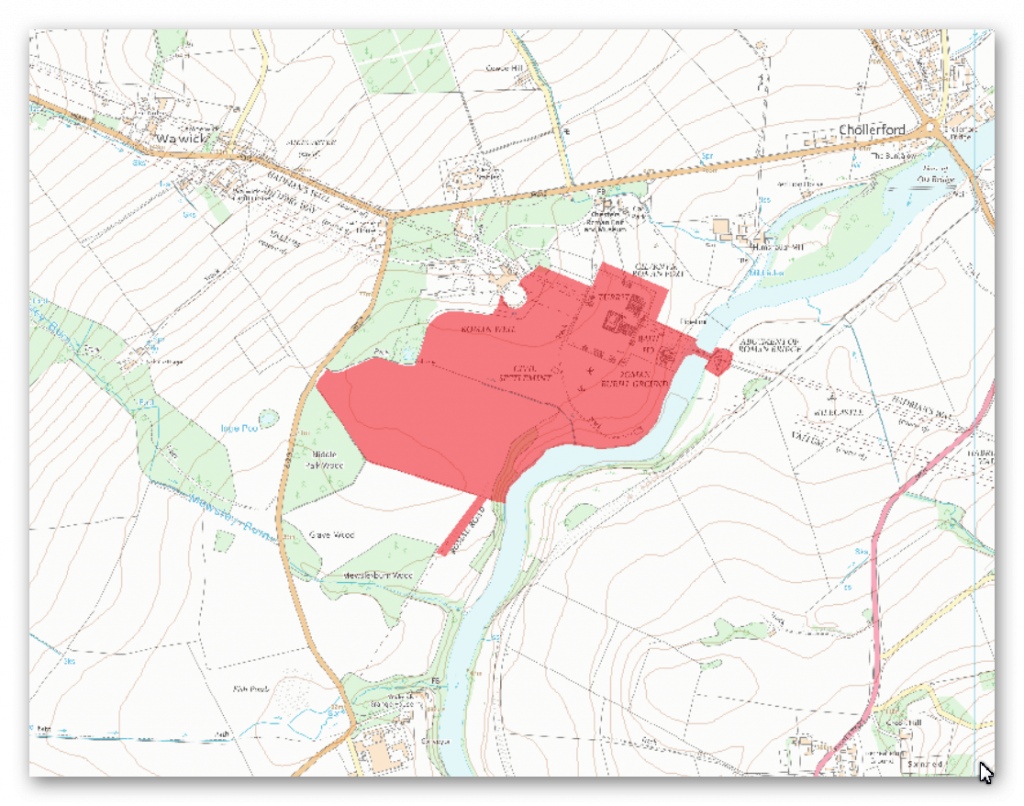

Name: The Roman fort, vicus, bridge abutments and associated remains of Hadrian’s Wall at Chesters in wall mile 27

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010959

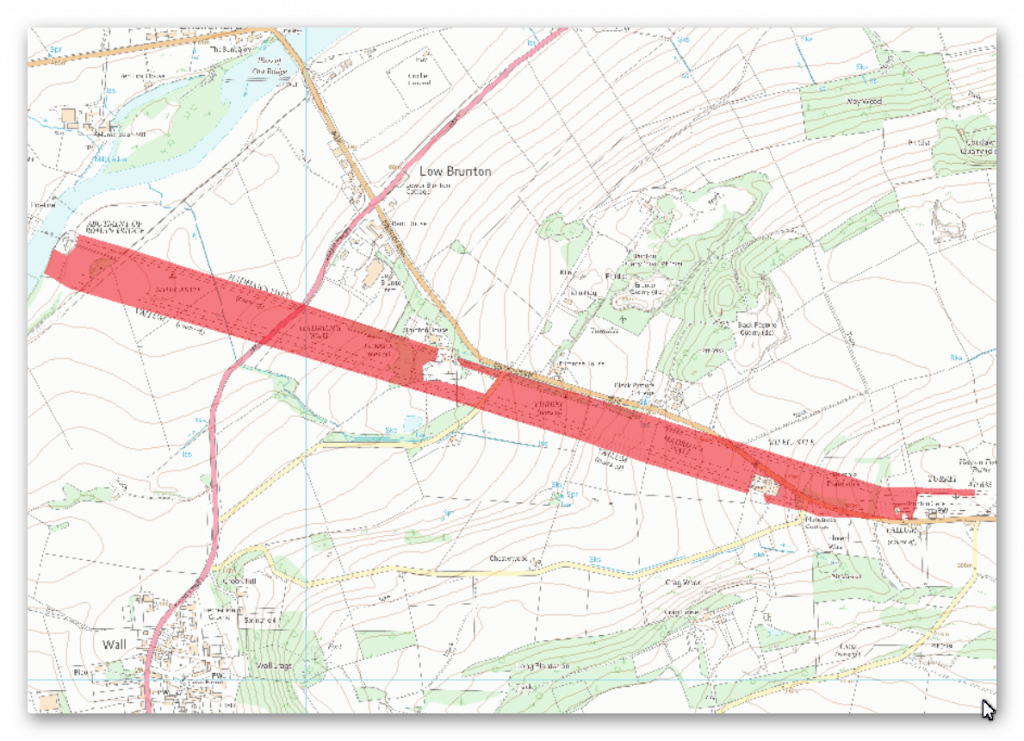

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between St Oswald’s Cottages, east of Brunton Gate and the North Tyne in wall miles 25, 26 and 27

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1018581

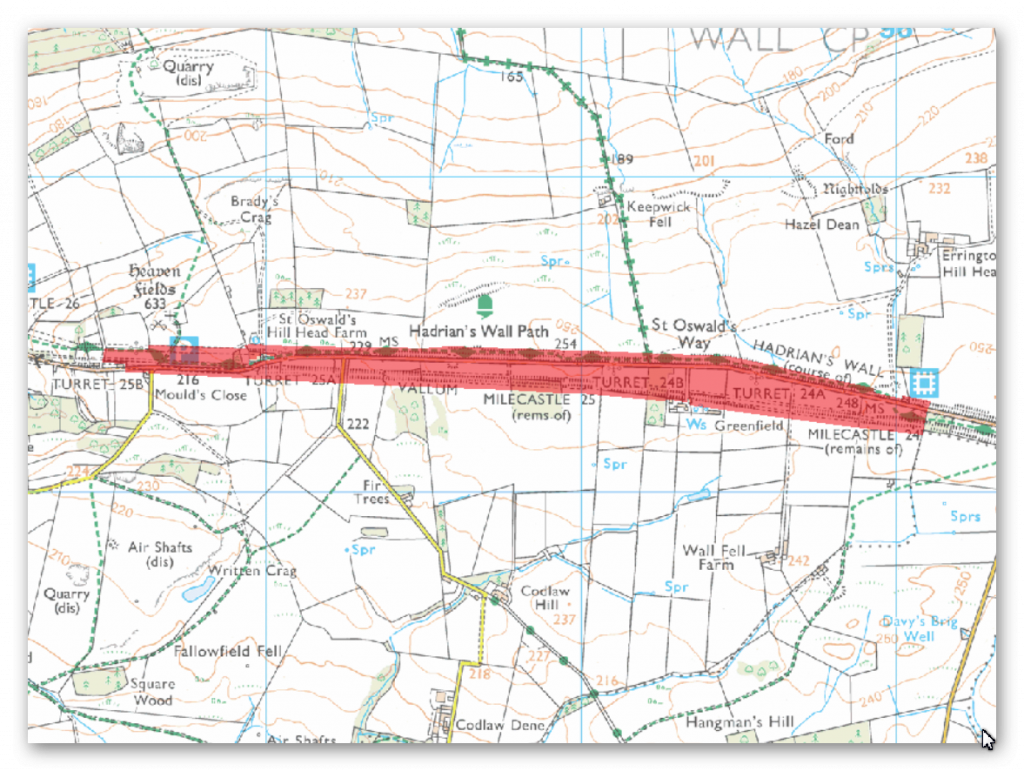

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between field boundary east of milecastle 24 and field boundary west of the site of turret 25b in wall miles 24 to 25

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010958

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and associated features from the bridge abutment on the east bank of the River North Tyne in the east to the woodland on the east side of the Chesters property in the west.

This section of frontier, which includes Chesters fort (known to the Romans as Cilurnum) occupies a broad stretch of river terrace on the west bank of the North Tyne. The Wall is visible intermittently as an upstanding feature in this section. Short sections of Wall are upstanding at the junctions with the fort on the south sides of the east and west gateways. There is a 6.7m length of consolidated Wall to the east of the fort which is in the care of the Secretary of State. West of the fort the Wall line is denoted by an amorphous, discontinuous mound up to 0.4m in height. There are no visible upstanding remains west of the ha-ha (sunken wall), which forms an element of the landscape gardens of Chester House. The wall ditch is discernible to the east of the fort as a ploughed down upcast scarp. For the most part it survives as a silted up feature below the surface.

To the west of the fort the ditch survives as a discontinuous depression, 0.3m deep. Turret 27a which occupied part of the site before the fort was built was discovered by excavation during 1945. It was found to lie about 42m west of the inner face of the east gateway. The bridge abutments and piers which carried the Wall and Military Way over the River North Tyne survive well as upstanding monuments.

There is also a section of consolidated Wall and tower base adjoining the east bridge abutment on its west side. Excavations of the abutments by Bidwell and Holbrook during 1990 have shown that there were two clear phases to the bridge; the early Hadrianic structure and the larger and more imposing one of third century AD. The precise location of the vallum around Chesters has not yet been confirmed. Aerial photographs show the possible start of it from near the west bank of the North Tyne, but around the fort the course is conjectural.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, survives well in the section between the North Tyne and the fort. The line of the road is clearly defined on the ground leaving the fort by the east gateway and heading towards the Roman bridge. Initially it is a depression and then becomes a causeway with a maximum height of 0.8m with a kerb to the south visible for 1.3m. There are no upstanding remains of the road to the west of the fort. However, the antiquarian Horsley considered that the Military Way exited Chesters and then converged gradually with the north mound of the vallum where they continued united for a considerable distance.

The Roman fort at Chesters, which is in the care of the Secretary of State, was built to guard the North Tyne crossing of the Wall. Excavation has demonstrated that the fort was constructed after, and overlies, the Wall. It encloses an area of 2.1ha. The fort wall is exposed in a number of places round the circuit. Elsewhere the outline of the fort is shown by a scarp which survives to a maximum height of about 2m. The upstanding masonry is best preserved in the south east corner where it survives to a height of 1.9m. Well preserved visible remains in the interior include the consolidated remains of the headquarters building, commanding officer’s house and some barrack blocks.

Buried remains will survive below the ridge and furrow cultivation inside the fort. The site has been excavated at various times from 1796 up to the most recent investigations during 1990-91. Extensive amorphous earthworks within the fort probably show the position of the backfilled trenches and spoil heaps, resulting from the various excavations. An extensive civil settlement, or vicus, is located outside the fort on the south side. It occupies an area of level ground bordered to the east by the steep cliff down to the river’s edge. Its buildings and roads are known largely from the evidence of aerial photographs. The settlement is orientated around the road leading south from the fort and a road which bisects it at right angles. A well, believed to be Roman, survives as an upstanding feature immediately outside the garden of Chesters house. The well preserved remains of a bath house are visible to the east of the fort about 30m uphill from the present course of the river. It had a paved floor, hypocaust and an outflow drain, as well as various hot and cold rooms.

An interesting and unique feature of this bath house is that when it was discovered in the 1880s the remains of 33 human skeletons, two horses and a dog were found. There is a however some doubt as to exactly where around the bath house they were found. A quantity of monumental masonry has been found by the river at the point where the ha-ha wall joins its bank, suggesting that this was the location of the cemetery. More recently an altar has been found in the river bank closer to the fort together with a fragment of architectural masonry. A road runs from the south gateway of the fort to the Stanegate Roman road which lies further south. Aerial photography has shown that this road runs along the crest of the river bank south of the ha-ha wall.

The monument includes the stretch of Hadrian’s Wall, vallum and associated features between St Oswald’s Cottages, east of Brunton Gate in the east and the River North Tyne in the west. This section occupies the west-facing side of the North Tyne valley.

Hadrian’s Wall bends slightly northwards at Dixon’s Plantation and then follows a straight alignment all the way down to the crossing of the North Tyne. The B6318 road runs to the north of the Wall line for most of this section. The Wall is visible as an upstanding monument only in parts of this section. There is a 35m stretch of consolidated wall showing the junction between broad wall and narrow wall, at Planetrees, which is in the care of the Secretary of State. A second stretch of consolidated wall, 69m long and including turret 26b, is visible west of Brunton House. This is also in the care of the Secretary of State. Finally a further section of the Wall about 100m long, from the disused railway to the bridge abutment is in the care of the Secretary of State.

Elsewhere throughout this section the Wall survives as a buried feature beneath grassland and dense woodland. The outer ditch is visible intermittently as a well-preserved earthwork. It is best preserved in the areas of woodland where it reaches depths of 3.5m. Milecastle 26, or `Planetrees’ survives as a buried feature, partly beneath the B6318 and the areas to the north and south of it opposite Planetrees Farm. Milecastle 26 was partly excavated during 1930 by Hepple. Milecastle 27, or `Low Brunton’ is situated on level ground on the east bank of the North Tyne. It is visible as a low, almost square, platform with a maximum height of 0.4m. The milecastle was partly excavated in 1952, and was shown to have a clay bonded wall core. The site of turret 26a was located opposite High Brunton House during 1930 by Hepple. It is situated on a steep east-facing slope. It survives as a buried feature below the dense woodland on the south side of the B6318. It was partly excavated during 1959 when it was shown to have had two levels of occupation, with no finds later than the second century AD. Turret 26b is a well-preserved upstanding example of a turret, up to 2.8m high. It is situated on a stretch of consolidated wall; both the Wall and turret are in the care of the Secretary of State. On the east side of the turret the broad wall wing of the turret is joined by a section of narrow wall, indicating that the turrets were built first and the Wall was then built up to them. This turret was first excavated by Clayton during 1873 and later by Hepple in 1930.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is considered to be on the line of the north mound of the vallum in this section. Throughout this section the north mound of the vallum has been largely levelled by ploughing and so it is doubtful whether the Military Way survives intact here. The exception to this is where the angle of descent down to the North Tyne is particularly steep opposite Black Pasture Cottage, and here a turf-covered trackway leaves the line of the north mound to run down the side of a dry valley to rejoin it some 180m further on. This diversion effectively eases the gradient. Where the valley opens out this track is visible as a raised causeway 7m wide and 0.2m high.

The vallum has been disturbed by ploughing in this section and for most of its length the mounds have been ploughed flat and the ditch only survives as a buried feature, now silted up. Intermittent sections of upstanding earthworks occur, the best preserved being to the west of Brunton Gate where the north mound survives up to 1.6m high and the ditch up to 1.7m deep.

A cemetery, probably associated with the Roman fort at Chesters, exists alongside the probable course of the Military Way as it approaches the river crossing of the North Tyne on its east side. Excavation works for the building of the now disused North Tyne railway in 1857 uncovered human bone, a burial urn and fragments of samian ware Roman pottery. Layers of burnt material were found underneath the line of the vallum mounds. This positive relationship between Roman cemeteries and approach roads to forts is becoming increasingly apparent, being evidenced elsewhere along the Wall at Great Chesters, Carvoran and Carrawburgh.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and its associated features between the field boundary east of milecastle 24 and the field boundary west of the site of turret 25b east of Brunton Gate. Throughout most of this section there are wide views to the north and south with undulating ground to the east and west restricting the outlook.

The Wall survives as a series of buried remains below the course of the B6318 road throughout most of this section. Where the B6318 road changes direction east of St Oswald’s Hill Head Farm the line of the Wall runs below St Oswald’s Hill Head Farm itself. Beyond the farm it survives as a turf covered mound 0.5m high, spread by ridge and furrow cultivation. The wall ditch survives well as an earthwork visible on the ground for most of this section. It averages about 2.5m deep throughout, though it reaches a maximum of 3.6m deep in places. The upcast mound from the ditch, known as the glacis, is visible intermittently, usually in places where it has survived ploughing. Where extant it is generally irregular, sometimes containing much stony material, and averaging about 1m in height. Milecastle 24 is situated just below the crest of a west facing slope with views to the north and south. It was partly excavated in 1930 by Hepple and was shown to be just over 15m across with walls 3m thick. It survives as a turf covered mound with the remains of the excavation trenches and spoil heap still visible. Milecastle 25 is also situated on a west facing slope with views to the north and south. It survives as a turf covered platform about 1m high. A slight hollow on the south side may indicate an outer ditch.

This milecastle was also partly excavated during 1930 by Hepple. Turret 24a occupies a slight hollow which restricts views to the east and west. It survives as a buried feature below the B6318 road. It was located and partly excavated during 1930 by Hepple. Turret 24b is situated just below the crest of an east facing slope with wide views to the north and south. It survives as a buried feature below the surface of the B6318 road. As with turret 24a this turret was located and partly excavated by Hepple during 1930. Turret 25a is situated on a west facing slope in the short stretch of ground between the B6318 and St Oswald’s Hill Head Farm. It was located by Hepple during 1930, however there are no upstanding remains. Turret 25b is situated on a west facing slope to the south west of St Oswald’s Church. There are no upstanding remains but it will survive as a buried feature, below the line of the east-west field boundary to the west of St Oswald’s Church. It too was located and part excavated during 1930 by Hepple. The turret was again partly excavated during 1959 and there was no pottery recovered later than the second century AD.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known for most of this section. It uses the north mound of the vallum as its base, certainly up to milecastle 25, along which it could be seen by Horsley who recorded it in his 1732 publication. A recent survey by the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England shows that the Military Way probably continued along the north mound of the vallum beyond milecastle 25 where Horsley could no longer trace it.

The vallum survives as an upstanding earthwork for much of this section where it mirrors closely the line of the Wall. The north mound averages about 1m where extant with a maximum height of 1.6m in places. The south mound also averages about 1m, but has a maximum height of 4m in places. The ditch is generally between 1.5m and 2m in depth where extant. Elsewhere it survives as a buried feature that has silted up.

Investigation

The Vallum in this section is seen in three sections. The first section seems to end quite abruptly when it’s halfway down a hill towards the river North Tyne. This only makes sense when we add the prehistoric shorelines for this river.

Another interesting feature is the location of the large round feature that would have been on the line of the Vallum if it continued on its course. This feature is currently a sunken garden feature of Chester House. A similar feature is found 600m South West to the ‘sunken garden’ and is identified on the 1800 OS map as a ‘Ingle Pond’. This would suggest that Chester House had a similar pond, probably constructed in the 18th century when the house was first constructed – this is another indication of the high water level at this period in this area as the sunken garden is currently dry.

The second section of the Vallum that is exposed in this section, seems to start immediately at the start of the current river shoreline but ends another ditch at 90 degrees, heading north. This looks like a presently unidentified defensive section of the Roman fort that is protecting the land bridge accross the River North Tyne. This section is unlikely to have been part of the vallum.

The last part of the Vallum that is in this section seems to start from the prehistoric shoreline that section one disappear into? As for Military Way, there is no indication of a separate road in this section and we can only speculate that it was part the Vallum banks – there is no indication that it crossed the North Tyne bridge.

Finally there is a suggestion that Stanegate can be found in the south of this section upto the River as shown on the Early OS maps – we can catagorily show that this is just not correct as their is no signs of the road over the hills.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.