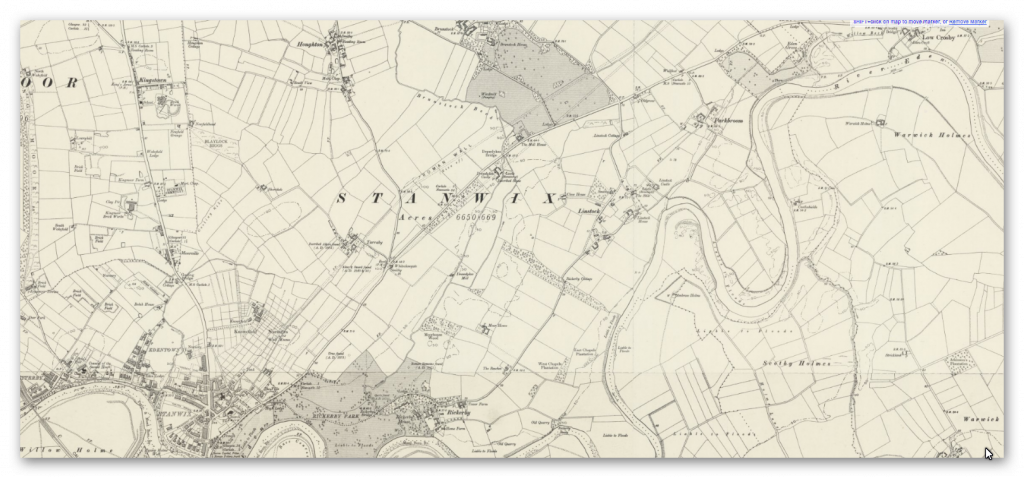

Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

Contents

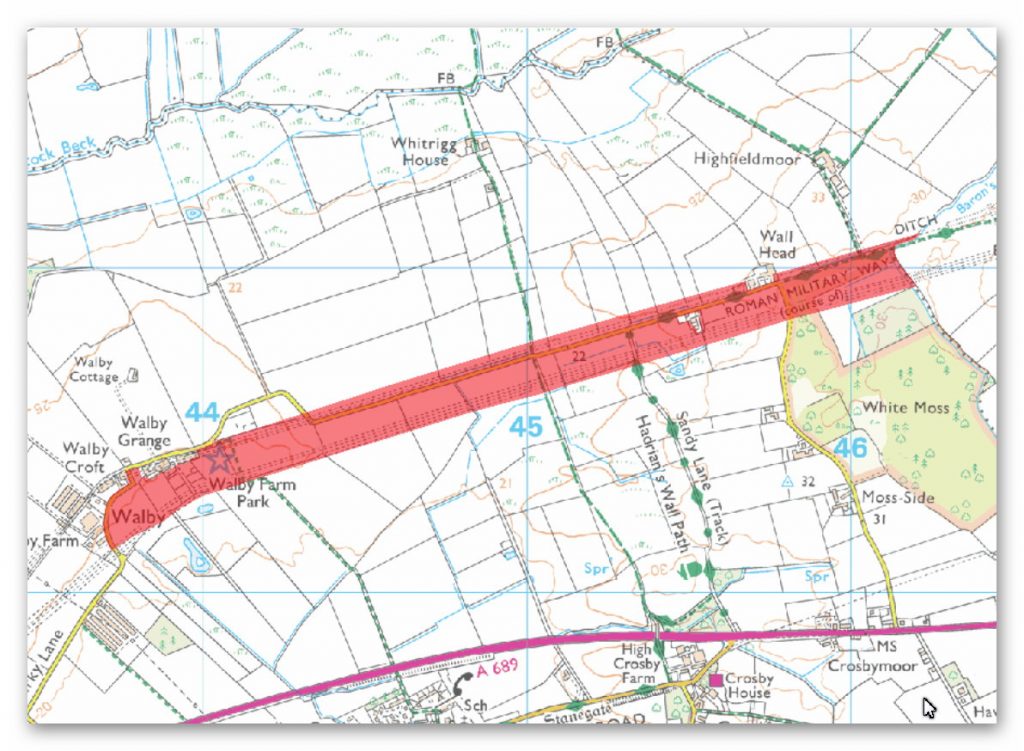

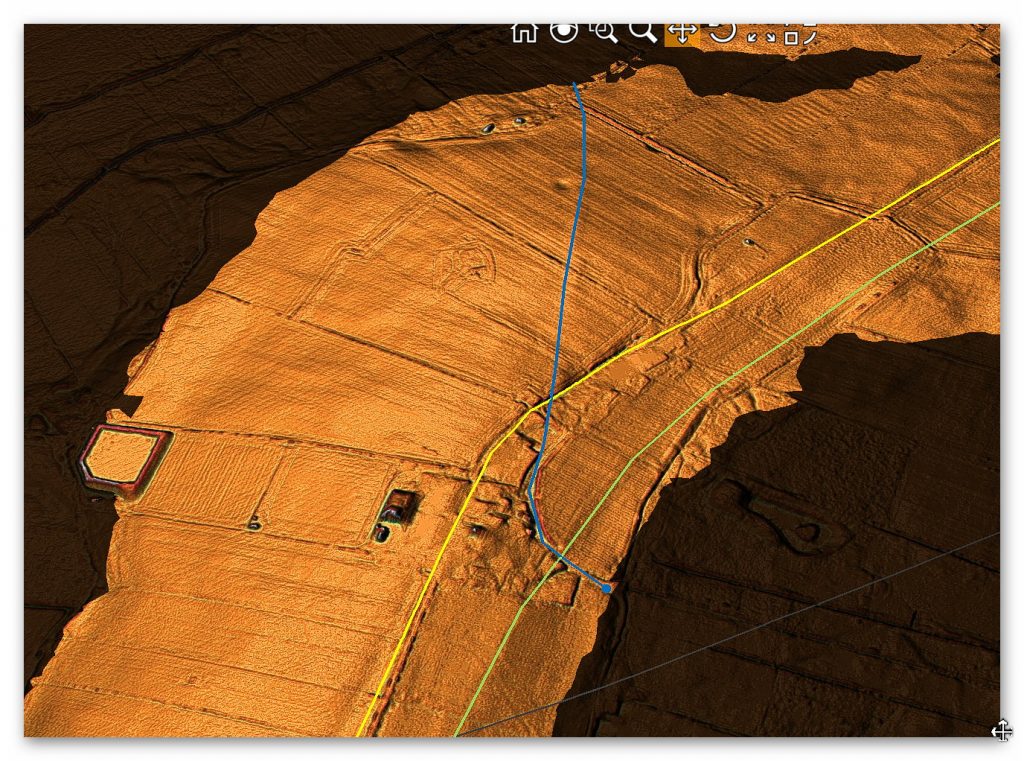

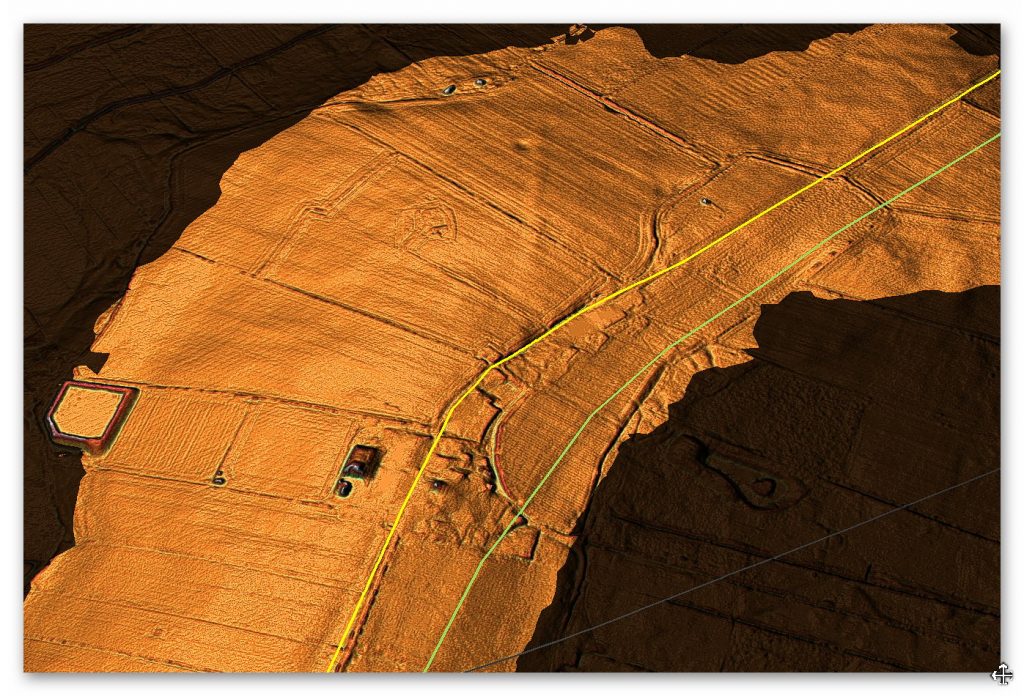

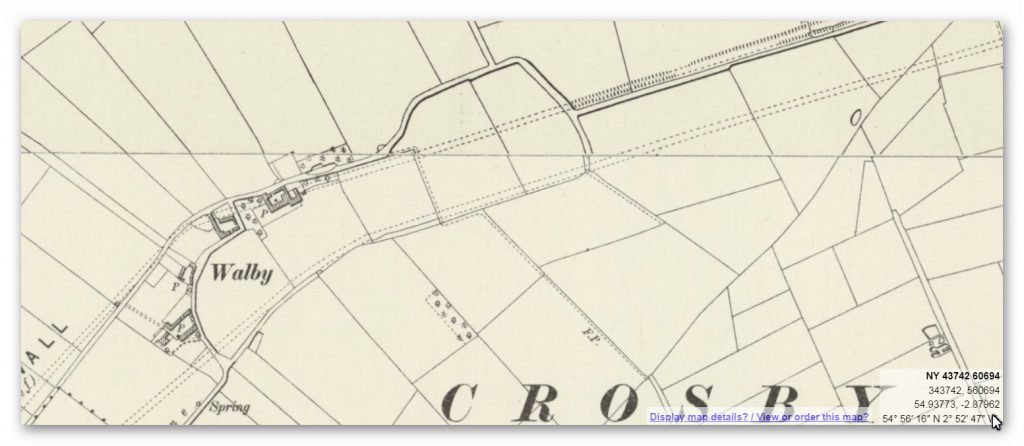

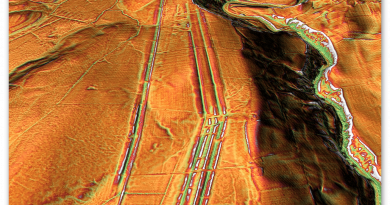

Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW – this is a section of Hadrian’s Wall showing the LiDAR, Google Earth and 1800 Maps of the Area covered by Historic England

Historic England Sections:

Hadrian’s Wall – between the east end of Davidson’s Banks and road to Grinsdale and vallum between Davidson’s Banks and dismantled railway in wall miles 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67 and 68

List UID: 1017942, 1017948, 1017946, 1017947, 1017945, 1017944, 1010980, 1010979,

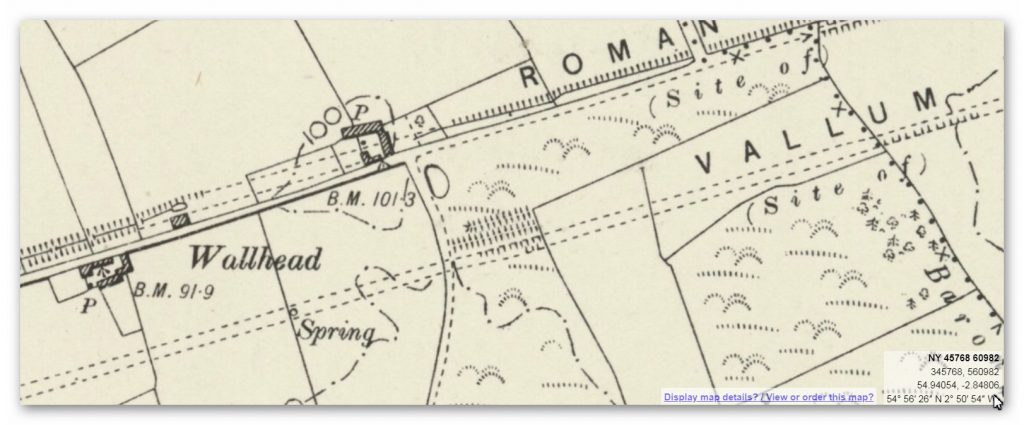

Old OS Map

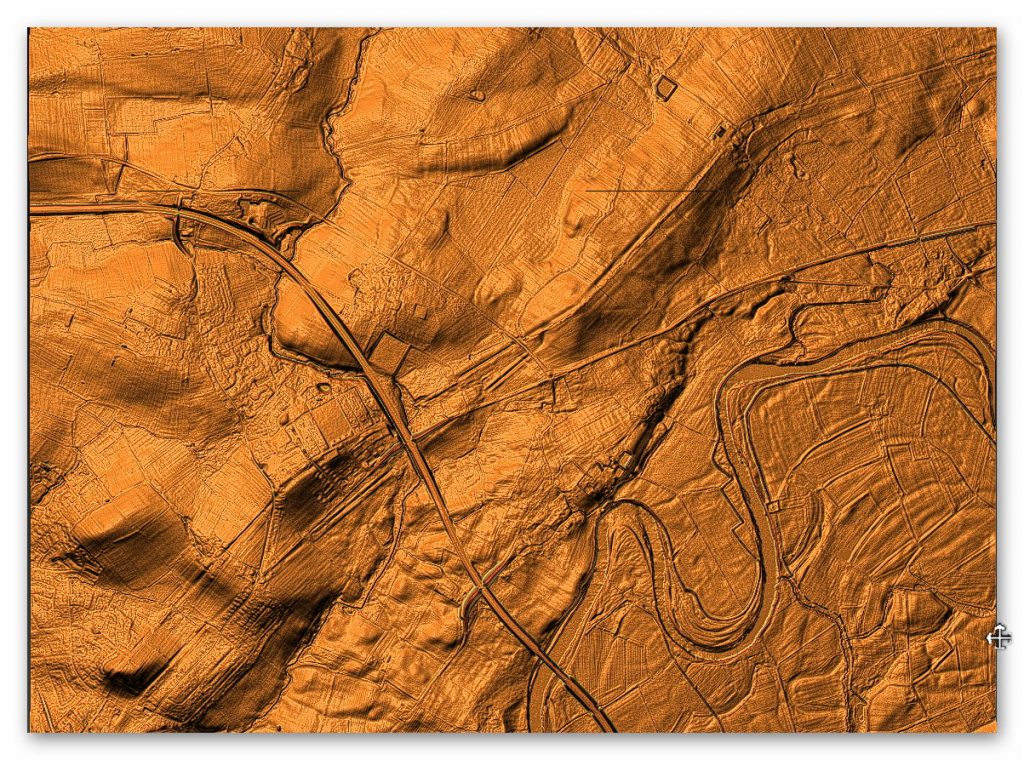

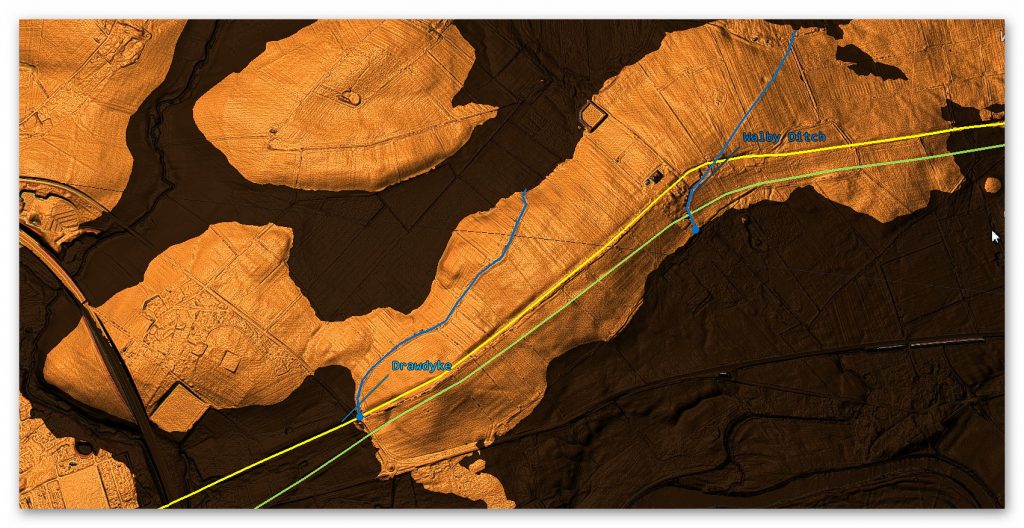

LiDAR Map

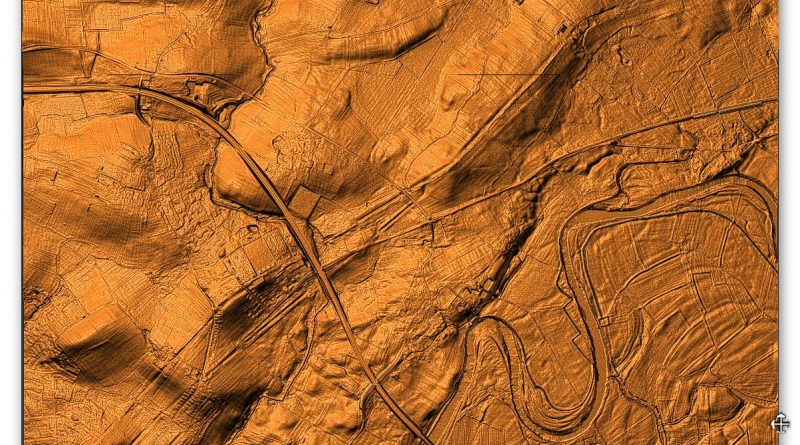

Google Earth Map

Historic England Scheduled Monuments within Section E

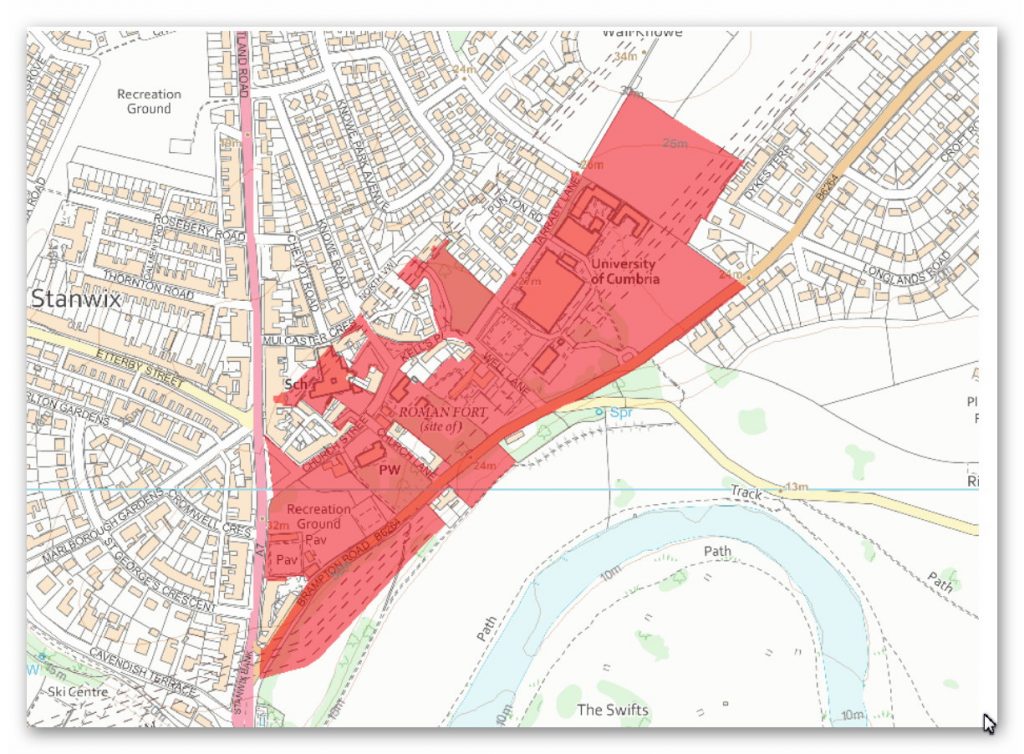

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between the field boundary west of Wall Knowe and Scotland Road including the Roman fort at Stanwix in wall mile 65

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1017948

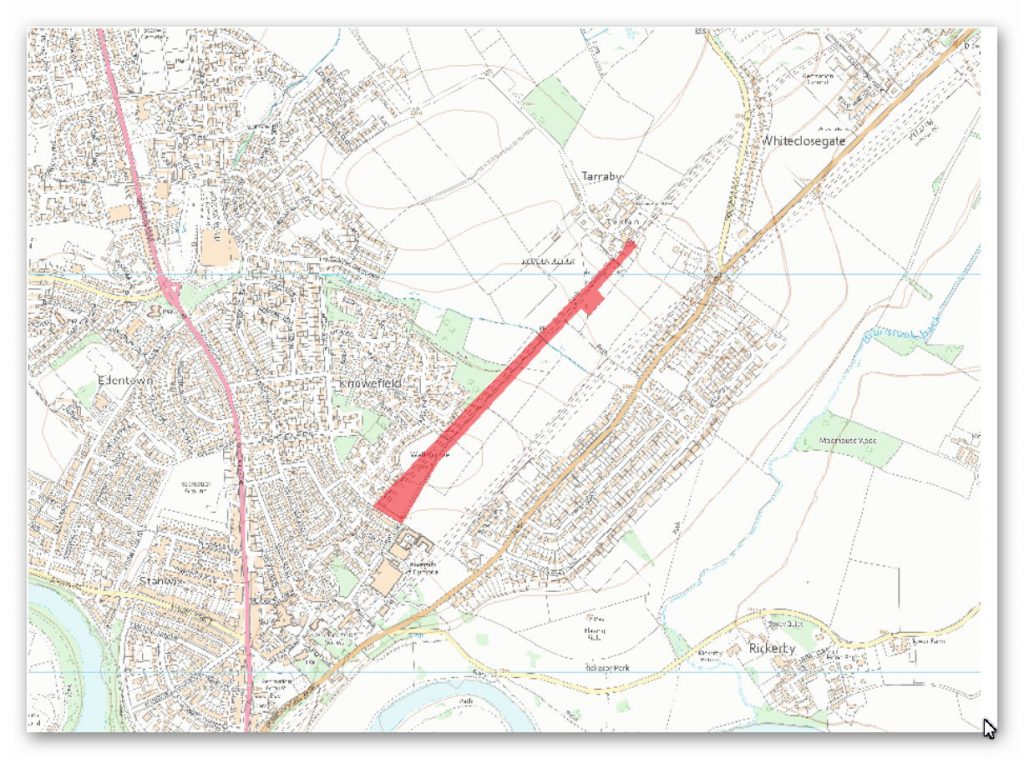

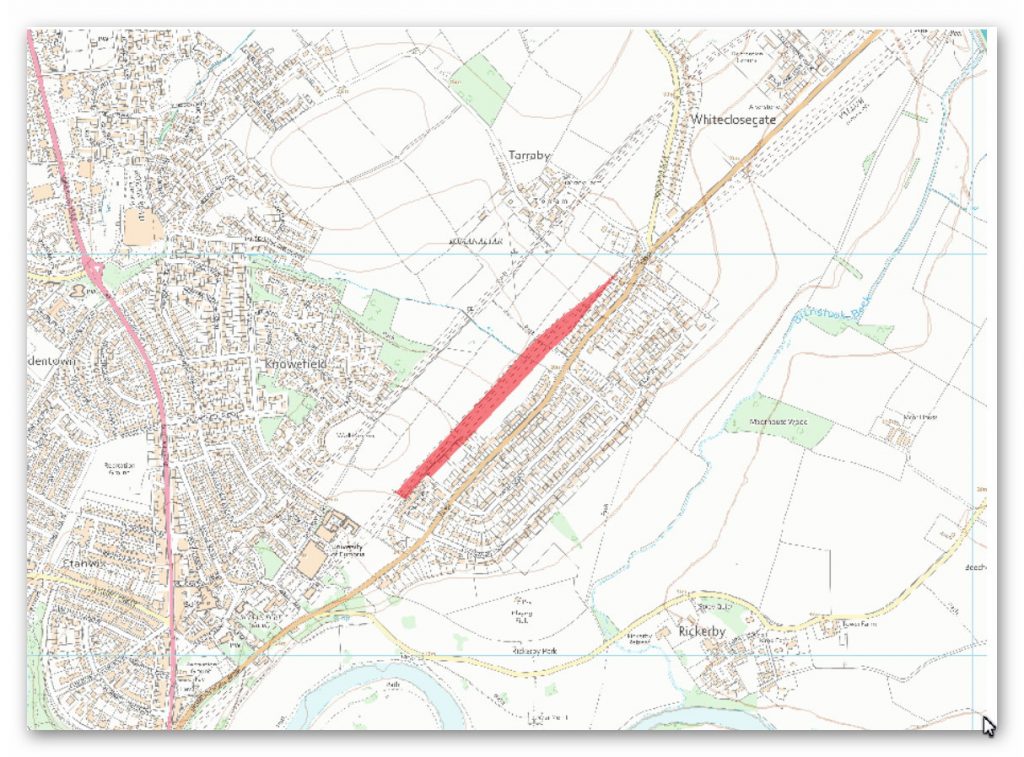

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between Tarraby and Beech Grove, Knowefield in wall miles 64 and 65

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1017946

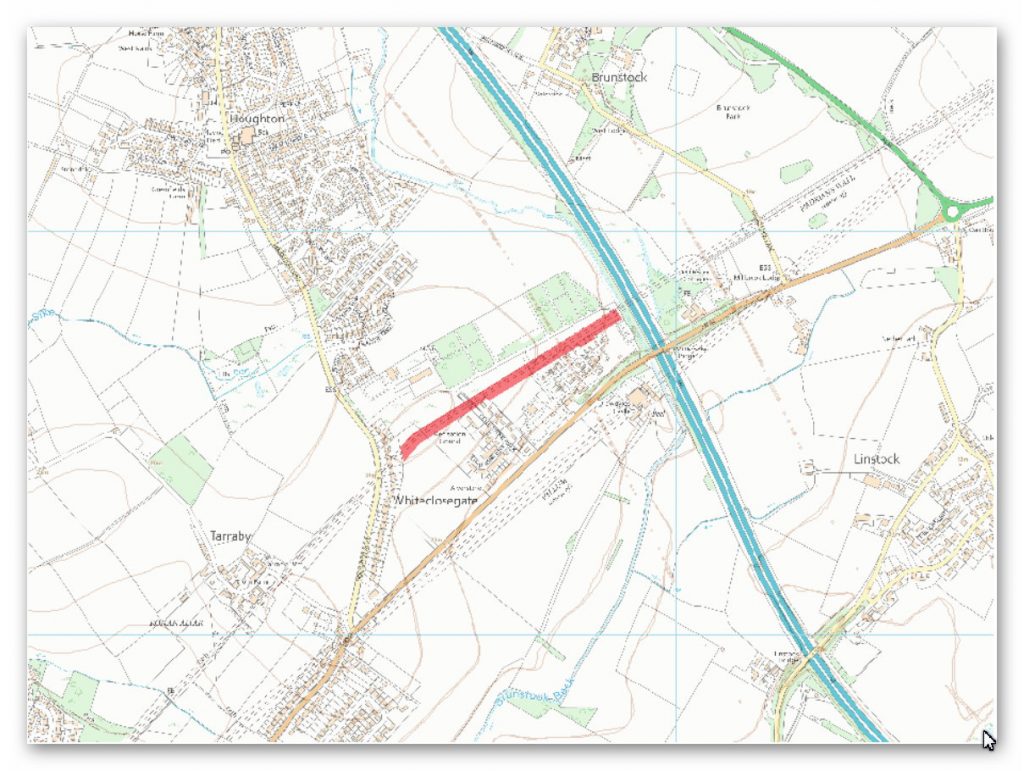

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between Houghton Road and Tarraby in wall mile 64

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1017945

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between the M6 motorway and the property boundaries to the east of Houghton Road in wall mile 64

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1017942

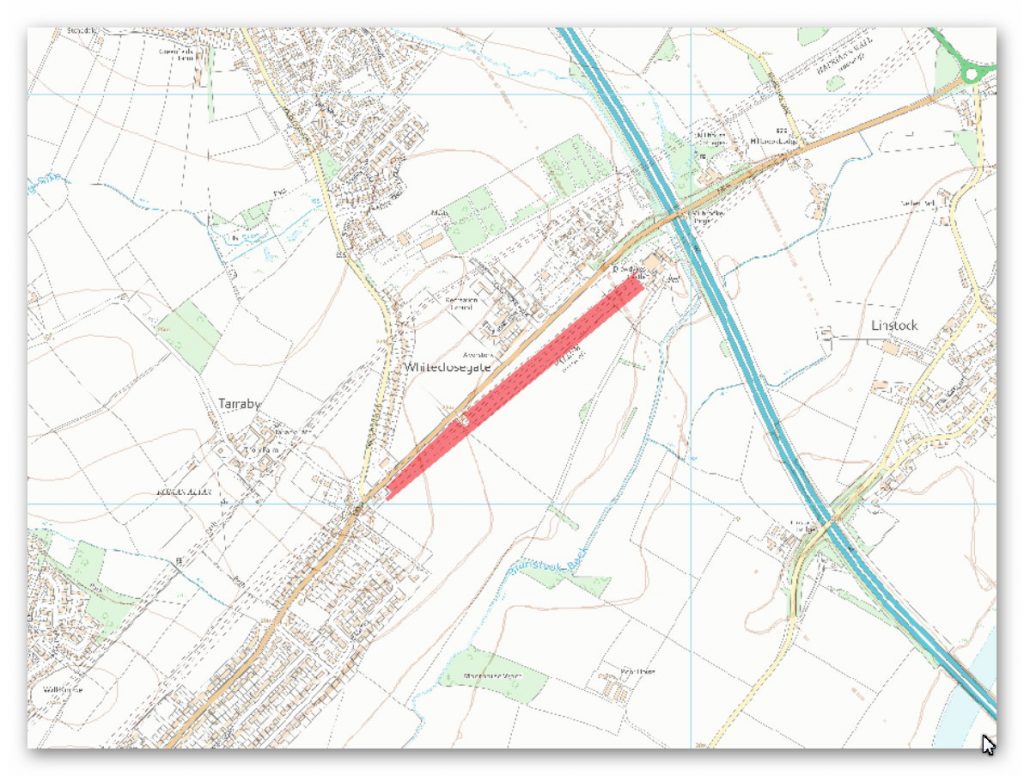

Name: Hadrian’s Wall vallum between the boundaries north of the properties on Whiteclosegate and the field boundary west of Wall Knowe in wall miles 64 and 65

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1017947

Name: Hadrian’s Wall vallum between Drawdykes Castle and Whiteclosegate in wall mile 64

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1017944

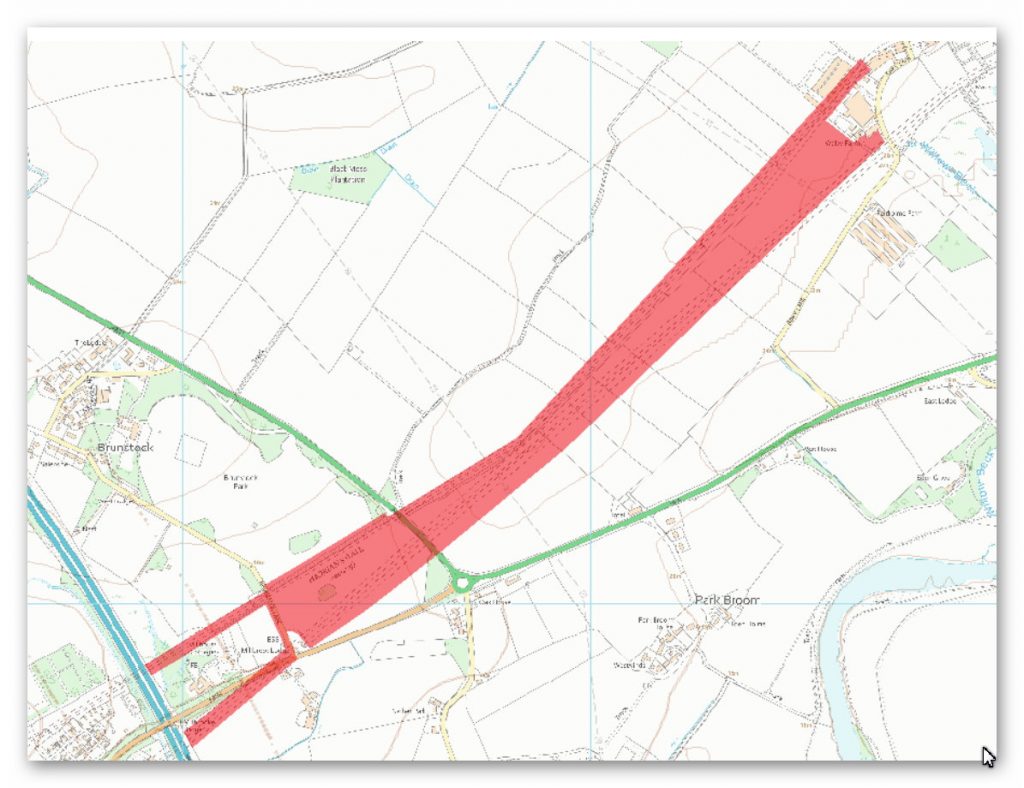

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between Birky Lane at Walby and the east side of the M6 in wall miles 62 and 63

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010980

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between Baron’s Dike and Birky Lane at Walby, in wall miles 60, 61 and 62.

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010979

Analysis of the GE map and English Heritage scheduled monuments confirms the termination point of the Vallum. Their report of these monuments suggests that:

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and associated features including a significant area of the site of the Roman fort at Stanwix, and the vallum between the field boundary west of Wall Knowe in the east and the east side of Scotland Road in the west. The Wall, vallum and the fort at Stanwix are situated on the crest of a ridge on the north side of the River Eden, with extensive views to the south across the city of Carlisle towards the northern Pennines, the Eden valley, and the Lake District fells, and also with views to the north for up to 5km.

Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout this section with no indications of the Wall or the wall ditch visible on the ground. The Wall in this section was initially built in turf, and later converted into a stone wall, possibly in the second half of the second century AD. A length of the stone-built Wall was found in excavations by Simpson in 1932 within the playground of Stanwix Primary School. An evaluation by Carlisle Archaeological Unit in 1997, also within the school playground, found a turf feature 7m to the rear of the Stone Wall, possibly remains of the primary Turf Wall.

Much of the course of the Wall adjacent to the fort is covered by housing and gardens, and these areas are not included in the scheduling as the extent of survival of the remains here has not been confirmed. The precise location of turret 65b has not yet been confirmed but on the grounds of the usual spacing it is likely to have been replaced by the fort at Stanwix when the latter was constructed. It would have been constructed at the same time as the Turf Wall and would have been identical in form to other Turf Wall turrets as a square tower the same width (6m) as the Turf Wall. It has not yet been confirmed whether turret 65b was replaced by the fort before or after the replacement of the Turf Wall by the Stone Wall.

The Roman fort on the Wall at Stanwix is known from excavations which have established the extent of its defences. It is thought the fort faced east, with its long axis parallel to Hadrian’s Wall. Its measurements until recently were considered to be 176m north-south by 213m east-west, arising from the evidence of the excavations by Simpson in 1932. The stone wall found was thought to have formed the north wall of the fort. Further excavations in 1940 by Simpson and Richmond on the other sides confirmed the position of the other three sides of the fort, including two parallel western ditches, the south west corner, a short length of the south wall and two fort ditches.

Part of an interval tower belonging to the south defences was found in the grounds of Stanwix House, and the east wall and a fort ditch was found where Romanby Close now runs. A linear earthwork at the southern end of the churchyard appears to reflect the line of the southern defences. Excavations in 1984 by Carlisle Archaeological Unit in the former gardens of Nos 24-28, Scotland Road, now the car park of the Cumbria Park Hotel, discovered a previously unknown north fort wall and interval tower 18m north of the wall found by Simpson, which suggests that the fort was at some time enlarged northwards, giving an overall north-south dimension of 194m. This would have made it the largest fort on Hadrian’s Wall extending over an area of 3.96ha.

The garrison is known from epigraphic evidence to have been the ala Petriana, which was the only thousand-strong auxiliary cavalry unit in Britain. The Roman name of the fort was traditionally thought to be Petriana, but recent research has suggested that this name arose from a scribal error in Roman times which confused the fort’s name and the occupying unit. Its true name was probably Uxelodunum, which means `high place’ and suits the fort’s topographically commanding position. Details of the internal layout are only partly known. The excavations in 1932 by Simpson revealed buildings parallel to the fort’s north wall although their function is unknown, and the excavations in 1940 by Simpson and Richmond in the southern part of the school yard of Stanwix Primary School revealed part of a granary and a further unknown building.

The walls of the granary are currently marked in red concrete in the school playground surface. An evaluation by Carlisle Archaeological Unit in 1997 confirmed several of the features identified by Simpson, and established that the buried remains survive well up to 1.5m in depth between 0.2m and 0.4m below the playground surface. All the remains of the fort survive only as buried features with no remains visible on the ground surface. A clay feature, interpreted as the parade ground attached to the fort, has been identified in excavations by Carlisle Archaeological Unit in 1991 and 1992 in the dip in the land east of the fort in the grounds of Cumbria College of Art. It consisted of a dump of clay up to 0.6m deep with a metalled surface which had been laid over a buried land surface containing traces of pre-Wall cultivation. This in turn had been cut by a Roman military ditch pre-dating the parade ground.

The full extent of the parade ground has not yet been defined but it does not extend as far eastwards as the field boundary which marks the eastern limit of the monument and is confined by the line of Hadrian’s Wall to the north and the fort to the west. The parade ground is not visible on the ground surface and survives wholly as a buried feature. The full extent of the civil settlement, known as a vicus, belonging to the fort at Stanwix has not yet been confirmed, but it is known from excavations to have extended both to the east and west of the fort. There are no remains visible above ground and it survives entirely as buried remains.

A series of ditches associated with second century AD pottery is known from excavations by Smith in 1976 on the site of Vallum Close adjacent to Brampton Road. As the remains here were totally excavated, this area is not included in the scheduling, although the area immediately to the west, south of the vallum, is included. Observations of development on the site of the former Miles McInnes Hall by Caruana in 1986 also found traces of buildings and occupation belonging to the civil settlement on the west side of the fort, dated to the second half of the the second century AD. As the remains here were totally destroyed by development, this area is also not included in the scheduling. It is possible that the civil settlement may have extended further towards Carlisle although this has not yet been confirmed. It is unlikely that the area south of the fort below the steep river cliff was occupied because of the flood plain of the river.

The cemetery belonging to the fort lay east of the fort and is known from the chance discovery of cremation urns in Croft Road in 1872 and again from the construction of houses in Croft Road in 1936. The full extent of the cemetery has not yet been confirmed and the area of these discoveries has not been included in the scheduling as the survival of remains in the built-up area has not been confirmed. There is a strong possibility that the western part of the cemetery may lie within the area of protection. Two tombstones originating from the cemetery at Stanwix have been recovered, one of Marcus Troianus Augustus and the other of a cavalryman, but both have been moved, one to Drawdykes Castle and the other to the Senhouse Museum, Maryport.

The course of the road, known as the Military Way, that ran the length of Hadrian’s Wall connecting forts, milecastles and turrets has not been confirmed in this section. However a metalled road up to to 10m wide was identified in the excavations by Smith in 1976, in the adjoining scheduling to the east. This road ran south of and close to the Wall and was in use in the medieval period but it may have followed the line of the Military Way, the line being spread with continued use.

The deviation of Tarraby Lane from the line of the Wall west of Wall Knowe to run straight towards the probable position of the east gate of the fort would suggest that it follows the line of the Military Way. The line of the road on the west side of the fort has not yet been identified. Military Way is not visible on the ground and it survives as a buried feature.

The course of the vallum is known at either end of the monument from excavations. The vallum was located by excavation 100m east of Dykes Terrace by Simpson in 1932, and again immediately west of Dykes Terrace in excavations by the English Heritage Central Excavation Unit under Smith in 1976. Excavation in Rickerby Park by Simpson in 1934 has confirmed the course of the vallum west of the fort, including the turn of the ditch towards Hadrian’s Wall before it descends Stanwix Bank towards the river.

The course of the vallum was unsuccessfully sought south of the fort in excavations by Simpson in 1933 and 1934, when a ditch that was found and initially thought to be the vallum ditch turned out to be the south ditch of the fort. The course of the vallum south of the fort has not yet been confirmed although it is possible that erosion of the steep cliff above the river flood plain may have resulted in loss of some of the vallum south of the fort.

Milecastle 67 (Stainton) is a conjectured – Milecastle of the Roman Hadrian’s Wall. The location of the mile fort was determined by measuring the distance from neighboring mile forts. In 1861, some Roman coins were recovered from this point at the southern end of the railway viaduct over the Eden. However, upon follow-up, no remains or other evidence of its existence could be found.

Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout this section with no remains visible above ground. The course of the Wall has been confirmed by observations by Simpson in 1941 during the construction of Hadrian’s Camp, when the flag footings and the first course of masonry of the stone wall was found to survive. At the same time the ditch north of the Wall was exposed and excavated, its depth being recorded as 3.96m. Subsequent excavations in 1961 by Colonel Fane Gladwin found that the building of the World War II army camp had not affected the remains of the Wall which lay approximately 0.25m below the surface of the modern turf cover. Hadrian’s Wall in this section was initially built of turf before it was rebuilt in stone in the second half of the second century AD, and the 1961 excavations recorded remains of the turf surviving below the remains of the stone wall.

Milecastle 64 was located in 1962 during excavations by Fane Gladwin, 104m west of Brunstock Beck. It was of short axis type, being wider east-west than north-south, and measured internally 17.83m across east-west and 14.63m north- south. Its walls were found to have been extensively robbed but part of the north wall survived as far as the first course of facing stones. The north gateway, which was 3m wide, had been blocked at some stage. A cobbled road 5m wide ran through the centre of the milecastle, and outside the west wall was a cobbled area. The remains of Milecastle 64 survive below the turf cover as buried remains.

The precise location of turret 64a has not yet been confirmed but its remains are expected, on the basis of the usual spacing, to survive approximately 150m west of Centurion’s Walk, where the Wall changes direction.

The course of the Roman road, known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and vallum linking forts, milecastles and turrets, has not yet been confirmed in this section. However a cobbled road at least 9m wide was found in the excavations of 1961 by Fane Gladwin to the rear of the Wall which was thought to be medieval in date, but which may have been utilising the line of the Military Way. The remains of the Military Way are expected to survive below the turf cover as buried remains.

The monument includes the section of the vallum between the boundaries north of the properties on Whiteclosegate in the east and the field boundary west of Wall Knowe in the west. The vallum in this length runs through open fields on the south side of Wall Knowe, approximately 160m south of Hadrian’s Wall. The line of the vallum ditch is visible in the eastern part of this section as a broad depression 10m wide and 0.5m deep. The vallum’s banks have been reduced and dispersed by cultivation in the past and survive as buried remains.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall vallum between Drawdykes Castle in the east and Whiteclosegate in the west.

The vallum is visible as an earthwork throughout this section, although the profile of the vallum has been reduced by cultivation in the past especially towards the western end. The ditch is visible as a broad linear depression up to 9m wide and 1m deep. The vallum banks have been reduced and dispersed by past ploughing and are faintly visible above ground as broad swellings either side of the vallum ditch. The mounds survive mainly as buried features.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and vallum and their associated features between the west side of Birky Lane at Walby in the east and the east side of the M6 motorway in the west. Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout this section with no remains visible above ground except for a low amorphous turf covered mound at Brunstock Park.

However, a geophysical survey in 1981 and trial excavations by the Cumbria and Lancashire Archaeological Unit in 1989 have confirmed the course of the Wall at various points along this section. The wall ditch survives intermittently as an upstanding earthwork in this section. At Brunstock Park the ditch is 8m-9m wide and 1.2m deep. It is cut in the east by a tractor crossing. Excavations were carried out here by Haverfield in 1894. Approximately 120m west of Walby Hall excavations by Goodburn in advance of the laying of a gas pipeline in 1975 encountered the ditch which measured 10.5m wide and 3.7m deep. Elsewhere the ditch is silted up but can be traced as a very faint depression in the fields, 0.15m deep.

A geophysical survey in 1981 has shown that the wall ditch runs fractionally north west of its mapped line in two transects east of the electricity pylon line. Milecastle 63 probably survives as a buried feature. A geophysical survey in 1981 produced strong indications that it was located at a position WNW of the ninety degree bend in Birky Lane south of the poultry houses. The site has not been excavated so this location has not yet been confirmed to be that of milecastle 63. The exact locations of turrets 62a, 62b, 63a and 63b have not yet been confirmed. They are expected to be located at the usual spacings between the milecastles, approximately 500m apart.

The position of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has not yet been confirmed throughout this section. The only part of it which is known is a short section found during excavation by Haverfield in 1894 approximately 80m west of the minor road between Houghton Hall and the B6264 road, 40m south of the extant wall ditch. The excavation revealed a denuded road, 6.5m wide, flanked by small side ditches. Elsewhere its remains survive as buried features.

The vallum survives as slight earthwork visible on the ground in Brunstock Park. The broad line of the ditch averages 0.4m deep and the ploughed down north and south mounds stand 0.2m high. Excavation of part of the vallum was carried out here by Haverfield in 1894. Elsewhere in this section its remains survive as buried features with no remains visible above ground. However, its course has been confirmed through geophysical survey in 1981 and in 1991.

The various transects show that between Walby and the `pinch’ where the Wall and vallum are closest, the actual course of the vallum lies slightly to the north of where the course is depicted on Ordnance Survey maps. Excavations by Goodburn in 1975 in advance of the laying of a gas pipeline south west of Walby Hall located the vallum ditch 36m to the north of the line shown on the Ordnance Survey maps.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and vallum and their associated features between Baron’s Dike in the east and the west side of Birky Lane at Walby in the west.

Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout this section. Its course is depicted on MacLauchlan’s survey of the 1850s, but this course has not been confirmed in modern times. The Wall and its ditch were located during an excavation in advance of pipe laying east of Walby. The wall ditch survives as an intermittent earthwork visible on the ground in the east half of this section, which also serves as a reliable guide to the course of the Wall here. Where visible the partly silted ditch averages 0.3m-0.8m deep with a modern drain cut into its base. Elsewhere the ditch is visible as a broad and shallow depression in the fields averaging 0.2m deep, also with a drain cut into its base. Its course has been confirmed in places through geophysical survey in 1981. In this section the ditch upcast mound, usually referred to as the glacis, survives as a feature faintly visible on the ground; elsewhere it survives as a buried feature.

The exact location of milecastle 61 has not yet been confirmed. On the basis of the usual spacing it is expected to be located near Wallhead. A geophysical survey in 1981 located the probable remains of the milecastle. The locations of milecastle 62 and turrets 61a and 61b have not yet been confirmed. On the basis of the usual spacing milecastle 62 is expected to be situated approximately 300m east of Walby Grange. Turrets 61a and 61b are expected to be situated at the usual distances between milecastles 61 and 62.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has been identified for a short distance to the east of Wallhead. There are no remains visible on the surface except for a short section of a turf covered mound, 4m-5m wide and up to 0.4m high. Its course was confirmed during excavation in 1894 by Haverfield. The road consisted of a gravel layer laid over larger stones with a stone kerb and central spine. Its survival here was confirmed by geophysical survey in 1981. However, the unusual survival of this section suggests the possibility that it was reused in the medieval period serving as access to Bleatarn Quarry.

South east of Wallhead the vallum survives as a slight earthwork visible on the ground as four parallel mounds, the most prominent ones being up to 1.2m high. Excavations by Hodgson took place here in 1894-5. Elsewhere the vallum survives as a buried feature with no remains visible on the ground except for a slight depression over the vallum ditch in a field 600m east of Walby Grange. However, the course shown on the Ordnance Survey map has been confirmed throughout this section by geophysical survey carried out in 1981. With the exception of the area to the east and south of Walby where three geophysical transects south of Walby Grange and Walby Croft showed the line of the vallum running about 40m north of the position given on Ordnance Survey maps. An excavation cut about 750m east of Walby Grange at the same time as the survey confirmed that the features picked up on the geophysical survey were those of the vallum.

Analysis of this section shows that the Wall follows the high ground and the Vallum seems to dip into the higher water levels of the River Eden. If the builders wished to miss the water/marshland for the Vallum – they could have easily built both the Vallum and Wall a few hundred metres to the north and comidate both – but they didn’t for the only obvious reason of flooding the Vallum ditch with water.

Investigation

The Vallum in this section seems to appear some distance from the river Eden to the West Side – but this could be due to building work in recent years. The course of the Vallum stays on or very close to the raised height of the River Eden which we suspect is feeding the Vallum ditch with water. We have noticed in the LiDAR map a probable prehistoric Dyke feeding into and past the Vallum and Wall terminating in the raise water levels of what is now known as Brunstock Beck to the North. The strange ‘KINK’ (which is now a road) suggests that this was a Dyke that was at a later date altered to be the current road with unusually large impression on the landscape – this is proven as the Wall takes a straight line at this point where the road heads in a totally different direction then corrects itself for no apparent reason. This close connection to Dykes can also be found in placenames were the Vallum passes such as Drawdykes Castle and Baron’s Dike.

Not only do we see the Wallum dip into Paleochannels – we can see that some are deliberately built over springs which would have flooded the Vallum. But this is not the only prehistoric Dyke to intersect with the Vallum – This is either bad engineering or a deliberate attempt to flood the Vallum with water to make it a canal. Moreover, the dyke/Water connection is found at Drawsdyke where there is a bridge and Castle named after it. Both Prehistoric Dykes connect with the same two water sources – Eden River to the South and Brunstock Beck in the North.

To understand the problem with Hadrian’s Walls history read our article HERE.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Pingback: Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation - Prehistoric Britain