Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

Contents

Promotional Video – Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

Extract From Book……………………… Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke

The Introduction

Offa’s Dyke is seen as one of the two significant Linear Earthworks (of Britain) as it is supposed to be over 200 miles from Coast to coast dividing England from Wales and, consequently, was once one of the greatest battle grounds in history with this massive defence required to tame the barbaric hordes (like the Picts in Scotland) from the home of civilisation.

The problem with this flight of fancy is its complete nonsense, which this book can now testify. Sir Cyril Fox, in the 1950s, was most famous for producing his classic book ‘Offa’s Dyke – A field survey of the Western-Works of Mercia in the Seventh and Eight Centuries A.D.”, which detailed his field walking and observations on this most historic of Earth Battlements, which we have now seen from more scientific evidence available from LiDAR was nothing more than misinterpretations of the landscape to justify hypotheses that ‘didn’t hold water’ – but sadly for him, it did!

The harsh reality is that this ‘swiss cheese’ hypothesis was, as suggested, full of holes – over 200 of them, to be more exact, covering nearly 60% of this supposed Mercia defensive barrier with gaps large enough for people to walk through with ease.

Later archaeologists have attempted to remedy this false claim, yet it still is quoted by the likes of English Heritage, Historic Britain and CADW to fill the void of ignorance and lack of study. Consequently, this FIRST LiDAR study of Offa’s Dyke in detail has revealed many new truths which should progress our understanding of the past.

History

According to Historic England – Offa’s Dyke is the longest linear earthwork in Britain, approximately 220km, running from Treuddyn, near Mold, to Sedbury on the Severn estuary.

It was constructed towards the end of the eighth century AD by the Mercian king Offa, and is believed to have formed a long-lived territorial, and possibly defensive, boundary between the Saxon kingdom of Mercia and the Welsh kingdoms. The Dyke is not continuous and consists of a number of discrete lengths separated by gaps of up to 23km.

It is clear from the nature of certain sections that differences in the scale and character of adjoining portions were the result of separate gangs being employed on different lengths. Where possible, natural topographic features such as slopes or rivers were utilised, and the form of Offa’s Dyke is therefore clearly related to the topography. Along most of its length it consists of a bank with a ditch to the west.

Excavation has indicated that at least some lengths of the bank had a vertical outer face of either laid stonework or turf revetment. The ditch generally seems to have been used to provide most of the bank material, although there is also evidence in some locations of shallow quarries. In places, a berm divides the bank and ditch, and a counterscarp bank may be present on the lip of the ditch. Offa’s Dyke now survives in various states of preservation in the form of earthworks and, where sections have been levelled and infilled, as buried features.

Although some sections of the frontier system no longer survive visibly, sufficient evidence does exist for its position to be accurately identified throughout most of its length. In view of its contribution towards the study of early medieval territorial patterns, all sections of Offa’s Dyke exhibiting significant archaeological remains are considered worthy of protection.

The reality is that Offa’s Dyke is a complete mystery to archaeologists and historians as it is incomplete and varies from section to section. This is the first LiDAR survey of this ‘Earthwork’ undertaken for its entire length and every metre that’s supposedly marked in the Landscape.

The consequences of this survey changes the nature and understanding of this ‘Dyke’ to such an extent that it re-invents the history of this Scheduled Monument, which will have repercussions for decades to come.

But first, we must lay the ground to allow readers to understand what we are seeing in Offa’s Dyke, and so the following three chapters have been written to give the reader this background of understanding.

Chapter 4 – Offa’s Dyke

To survey this Offa’s Dyke successfully, we need to link to other historic providers’ information and maps. To do this with relevant accuracy, we need to establish a grid system that looks at all the LiDAR, Satellite photography, Old OS maps and excavation evidence to draw new conclusions about the construction of Offa’s Dyke.

Therefore, we have subdivided Offa’s Dyke into five sections and named them A to E – each Section is not equally divided but edited by the breaks within the Dyke. We have named these sections from South to North, which is a bit different from the norm, but in archaeology, information is the best way to approach Offa’s Dyke as you will find when you get to Section E.

These grid sections include the OS 1800 Map edition (for historical accurately, as new developments are not included), Google Earth Maps (showing Historic England Scheduled Areas and References) and our LiDAR (hi-resolution) maps, which are unique in their clarity and ease of landscape interpretation.

We will also give you a complete overview of the Dyke by section before the detailed analysis within the appendices. This will provide you with an understanding of the Dykes construction phases and function, allowing you to understand better how we came to our conclusions about Offa’s Dyke and when it was constructed.

Offa’s Dyke – Sections

Our Findings and Conclusion

Before we reflect on our findings section by section, it may be beneficial to look at the total statistics for some aspects of Offa’s Dyke, as such details have not been found in our research on this subject.

To illustrate the confusion over Offa’s Dyke and its interpretation, the length of the Dyke is now open to speculation as it has so many gaps. However, English Heritage has it as 82 miles (132 km) from Prestatyn in the north to Sedbury in the South and The Offa’s Footpath Trust – the charity set-up to promote the Dykes footpath suggests 176 miles (283 km) – slightly longer than Scheduled listing route.

While Historic England sits firmly in the middle with 137 miles (220 km) – We will look at Offa’s Dyke as it is commonly portrayed as a coast-to-coasts landscape feature covering 283 km (176 miles) from Sedbury Cliffs nr Chepstow to Prestatyn.

Sedbury Cliffs to Monmouth – 17.5 miles (28 Km)

Monmouth to Pandy – 16.75 miles (27 Km)

Pandy to Hay-on-Wye – 17.5 miles (28.2 Km)

Hay to Kington – 14.75 miles (23.3 Km)

Kington to Knighton – 13.5 miles (21.7 Km)

Knighton to Brompton Crossroads – 15 miles (24 Km)

Brompton Cross to Buttington Bridge – 12.3 miles (20 Km)

Buttington Bridge to Llanymynech – 10.5 miles (17 Km)

Llanymynech to Chirk Mill – 14 miles (22.5 Km)

Chirk Mill to Llandegla – 15.5 miles (25.7 Km)

Llandegla to Bodfari – 17.5 miles (28 Km)

Bodfari – Prestatyn – 12 miles (19 Km)

Offa’s Dyke

The Total length of Offa’s Dyke (including gaps and missing sections) 279,745m (173.8 miles)

Total length Found (by LiDAR): 95,044m (59.2 miles) – 34% of the entire length

Total length Missing (by LiDAR): 185,476m (114.6 miles) – 66% of the entire length

Total number of Gaps in the Offa’s Dyke – 70

Total number of Scheduled Monuments in Listing: 237

Features

Within the 59.2 miles of Offa’s Dyke, we have identified – within 200m of the construction:

118 (33 Natural Springs)/Wells/Ponds (as specified by the 1800 OS maps series – Wells and Ponds included to show high water table)

303 Quarries/Bell Pits (Bell Pits Ancient Quarry Holes) ave of 5 Quarries per mile of Dyke

12 Prehistoric Ancient Sites

4 Barrows

7 Roman Sites

52% of Sections are linked to each other

20% of Sections are connected to existing rivers

28% of Sections join Paleochannels

Summary

Section A – Total 20,201m. 14 Gaps – 6,758m missing (34%)

Section B – Total 110,545m. 10 Gaps – 106,768 missing (97%)

Section C – Total 55,905m. 17 Gaps – 7,990 missing (14%)

Section D – Total 56,369m. 22 Gaps – 29,848 missing (53%)

Section E –Total 36,725m. 7 Gaps – 33,101 missing (90%)

Our findings concluded that these landscape features are much more interesting and complex than the archaeologists currently imagine, as each Section has its individual interest that finally gives us a solution to the construction and functionality of the Dyke.

Section A – Runs around the hills surrounding Chepstow and the River Wye. This Dyke is no boundary or marker as the river would be a better solution to both causes. But what it does show is the connection to Quarries and Roman Roads that would have probably linked to the canal system it inherited from the ancient Dyke builders. These ‘linear earthworks’ were created to assist in trade during both prehistory and later Roman era until the canals dried up when the roads built upon the banks of these Dykes replaced the method of transport.

Section B – Shows why the Dyke is not interconnected, as 97% of it is missing, and there is not functionality or design that links together the small portions of Dyke that is in this section.

Section C – Has the least missing sections, yet it still has 14% missing with 17 gaps, indicating that these Dykes are a series of individual trading canals and not a single entity. This trading can be seen in the extensive quarries in this area which have been mined for their mineral wealth for thousands of years.

Each hill has a different design form the last when it comes to width and Depth of the Ditch. What we are seeing is a degree of uniformity in access to quarries and water sources and natural springs along the Dyke.

Section D – This is a 50/50 series of Dyke to gap ratio, again showing that it is connected to Quarries and Mining, particularly Coal Mining, which was widely used by the Romans. These are some of the largest coal mines in Britain and the Dyke does not just come close – it in some cases the alignment goes through the middle of these quarries, with on average four quarries per section which makes any suggestion that these Dykes were not used in conjunction with the minerals being extracted (as we see also in The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall) and were constructed for another purpose as completely absurd.

Section E – Even archaeologists (including Fox) now admit that this is a different series of Dykes (Whitford Dyke) and not part of Offa’s Dyke as its too dysfunctional.

So, our conclusion about Offa’s Dyke is that we are looking at a series of working Dykes – originally, built in prehistoric times and then utilised (as again we found in The Vallum) by the Romans to service the same Quarries for trading purposes.

In particular we see this Roman influence in Section D as these are Coal minerals which we know they used to heat the hypocaust underfloor furnaces of their Bath and home houses, which to date archaeologist have failed to investigate the sources of this coal and how it was transported.

Appendices

End of Section A

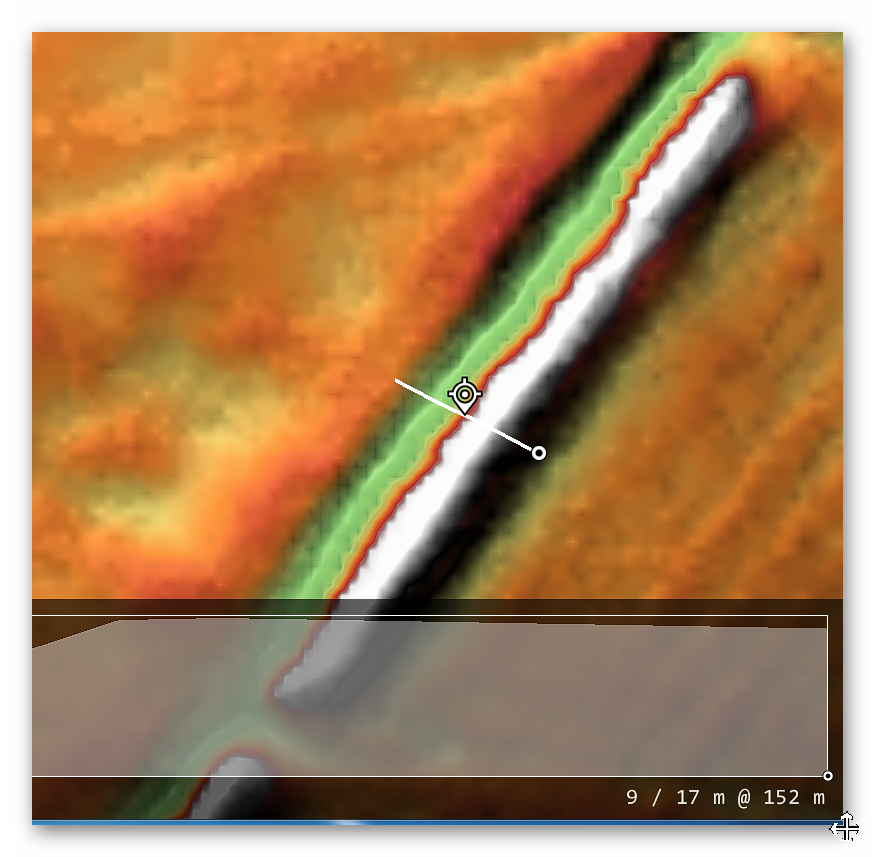

| Name (Section) | Highbury Plains, 370m west of Birt’s Barn: (A37) | ||

| 1020479 | Width(m) | Hght/Dth(m) | Length(m) |

| Bank | 10 | 1.0 – 2.5 | 360 |

| Ditch (facing) | 8 | 0.4 | ESE – ENE |

| Gap/Spring/Quarry | 0 | 1 | 1 |

“In this section, the Dyke is visible as a bank with quarry pits. The bank is about 10m wide at its base and stands to a maximum height of 2.5m on its western face and 1m on its eastern face. To the east of the bank are a series of quarry pits which are up to 8m wide and 0.4m deep.

Deliberately laid stonework has been exposed at intervals along the western face of the bank, and may be interpreted as the remains of a dry stone revetment acting as a near vertical, and highly visible, facing to the western side of the Dyke.

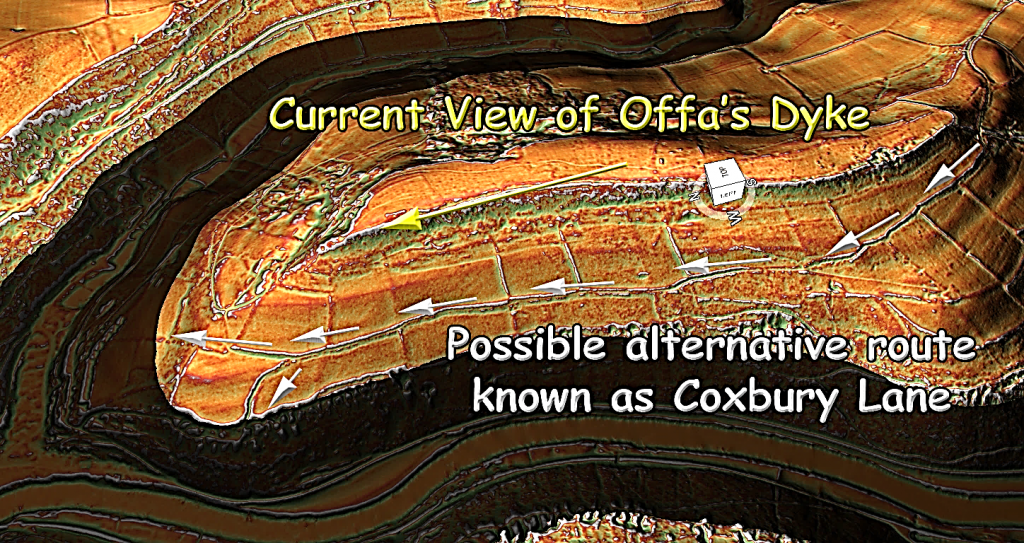

The lime kiln shown by the Ordnance Survey to the east of the line of the Dyke is in a ruinous condition and is thought to date to the 19th century. The line of the Dyke is interrupted by a track which is now called Coxbury Lane and is thought to be an ancient routeway leading to Wyegate, an early medieval manor about 2km to the south of the point where the lane crosses the Dyke at Highbury.” – Historic England

| Name (Section) | Highbury Plains, 770m South West of Glyn Farm (A38) | ||

| 1020478 | Width(m) | Hght/Dth(m) | Length(m) |

| Bank | 4 – 12 | 0.8 – 2.0 | 284 |

| Ditch (facing) | 4 – 8 | 1.0 | East |

| Gap/Spring/Quarry | 0 | 0 | 0 |

“In this section the Dyke runs for some 284m and is visible as a bank with quarry ditches to the east.

The bank runs along the edge of a steep slope and is between 4m and 12m wide at its base, standing to a maximum height of 2m on its western face and 0.8m on its eastern face.

The quarries, from which material was excavated during construction of the monument, are between 4m and 8m wide and up to 1m deep. The narrowness of the bank in places may be due to later quarrying, which appears to have taken place throughout this area.” – Historic England.

| Name (Section) | Highbury Wood, 460m west of Glyn Farm (A39) | ||

| 1020477 | Width(m) | Hght/Dth(m) | Length(m) |

| Bank | 4 – 6 | 4.0 | 579 |

| Ditch (facing) | 4 – 8 | 1.0 | East |

| Gap/Spring/Quarry | 0 | 0 | 4 |

“In this section, the Dyke runs for some 579m, and is visible as a terrace with a berm to the west and quarry pits to the east.

The hillside across which the Dyke runs is exceptionally steep, and the berm marks an artificial break in the slope, allowing the terrace to form a false crest to the slope. The berm is between 4m and 6m wide, and the terrace stands approximately 4m above it.

To the east of the terrace and berm, the quarry pits have been dug into the crest of the hill and are up to 1m deep, and between 4m and 8m wide.” – Historic England.

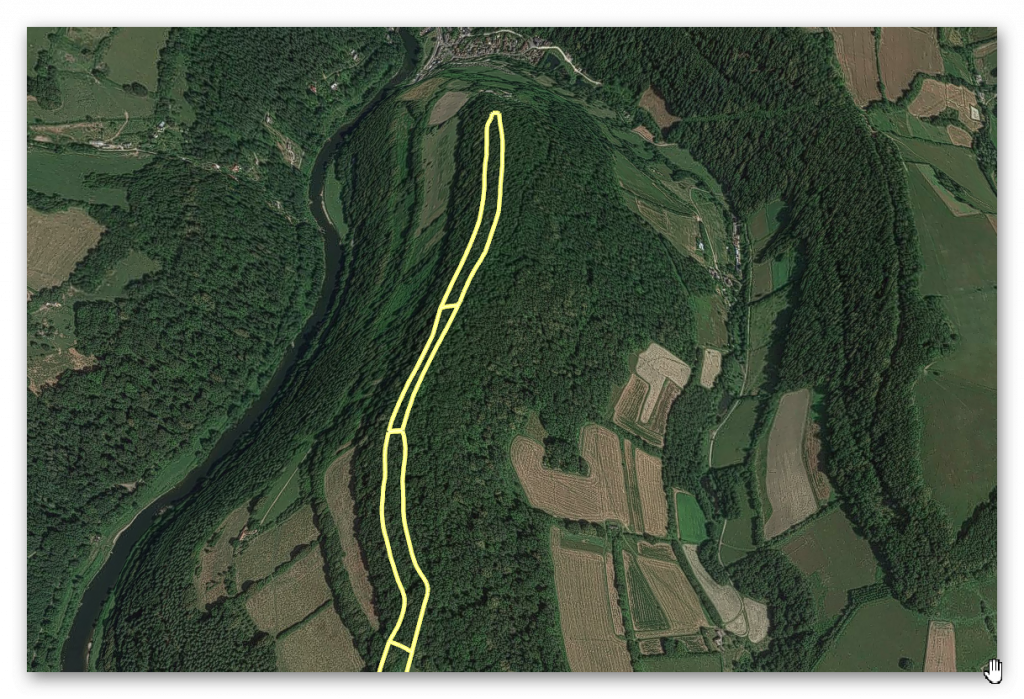

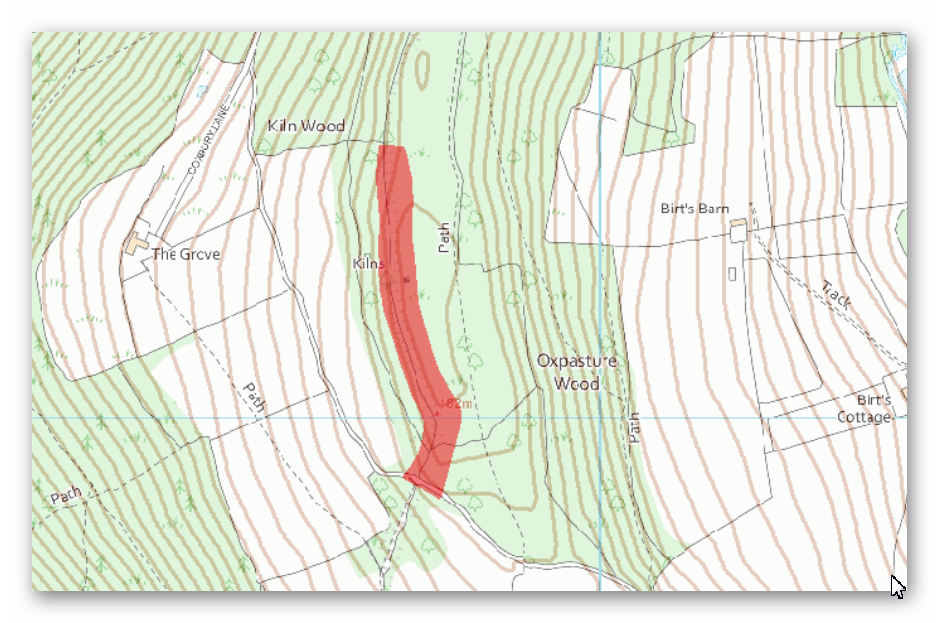

GE Map (all three sections)

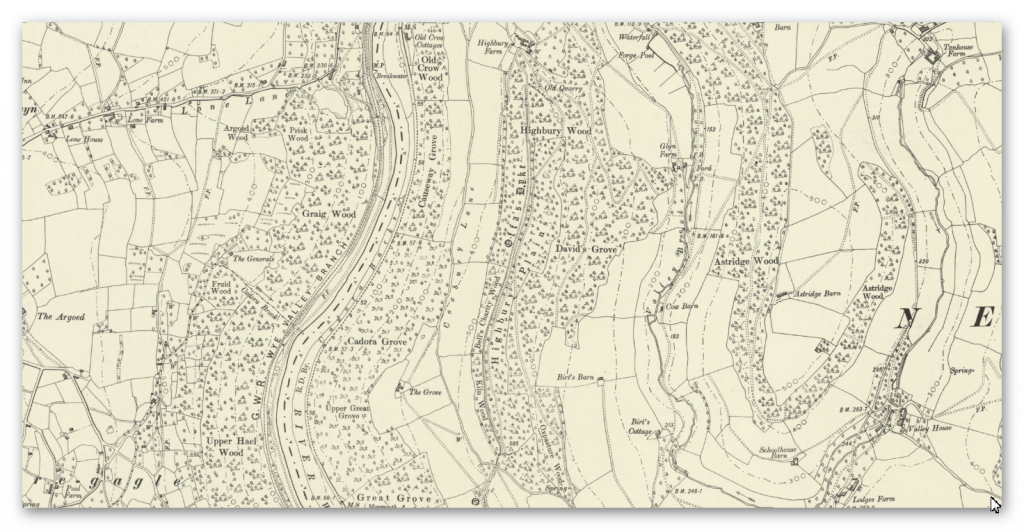

OS Map (First Section)

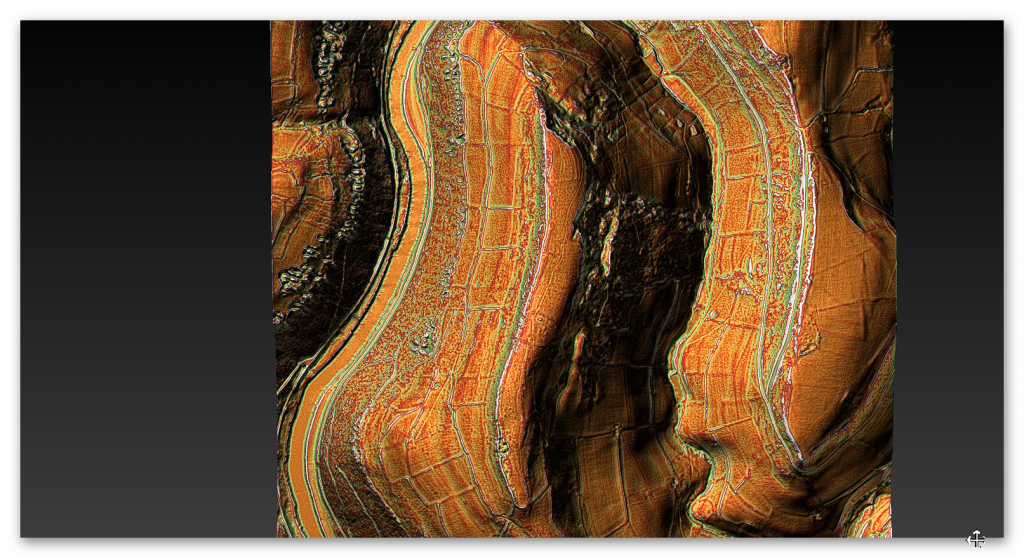

LiDAR Map

1800 Map

Conclusion

What should be noted is that the Dyke seems to come to an end at the top of the hill and then seems to swing down to the East with a bank and ditch at a later date not identified by archaeologists – but strangely it has not turned into a modern trackway using the Dykes bank as we have seen previously.

Coxbury Lane is made from a natural prehistoric ‘hollow’ and is very deep in places (much more profound than Offa’s Dyke), which would lead us to believe that this Paleochannel would have been flowing with water and effectively meet the Dyke, either terminating Offa’s Dyke of supplying it with water.

This section of Offa’s Dyke officially ends in the hills above the River Wye. But the Dyke at the top of the Hill is extremely ‘thin’ on features. What is of interest on top of this hill is another quarry and maybe the reason for the Dykes original construction.

Ave BANK Width = 9.99m

Ave BANK Height = 1.79m

Ave DITCH Width = 5.51m

Ave DITCH Depth = 1.00m

Features (within 200m)

Springs (1800 OS Map) = 25

Quarries (LiDAR) = 73

Ancient Sites = 2

Roman Sites = 3

Total Length of Section A = 20,201m

Total Missing Gaps = 14

Total Missing Dyke = 6,758m (34%)

Ave GAP missing Length = 482.7m

Section A is the most southernly 11 miles from Offa’s Dyke, and from the new statistics, we can now make some assumptions about the Dyke and its PROBABLE function. The traditional view of Offa’s Dyke (and hence his name) is a defensive earthwork to keep out the Welsh to the West.

The statistics do not support this hypothesis. The most obvious problem is that only 5% of Section A of the Dyke, faces only West; in fact, a higher percentage, 15% faces the utterly wrong way (East), and the majority (38%) has ditches on BOTH sides of the bank.

| Figure 64 – 11-mile section showing it was never a continuous feature – with banks on both East and Wes side and gaps in River Valleys – which fit the shoreline of prehistoric times – Offa’s Dyke (End of Section A) |

If the Earthwork were defensive, you would also expect the Counterscarp (which traps people in the ditch in theory) would be seen throughout – yet only 19% of this section has this feature. Moreover, the 14 Gaps open up a third (31%) of Section A for the enemy to walk through without difficulty.

This is the same as the idea of a political border marker. For this to be acceptable, the only feature you require is the Bank – which we do have. But again, there is no reason that 31% of the Boarder Marker is missing – especially when the Dyke follows the contours of the River Wye just some 500 metres to the East.

It is somewhat remarkable that archaeologists could imagine that the medieval cultures would not use the river as a marker (and/or a defensive barrier) rather than an earthwork which has a third missing (6,115m in this section) and as we will also see to a greater extent in Section B another 115,765m missing on top, to disqualify this irrational theory.

This was an extracts from the NEW Book Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke available on Amazon as a FULL COLOUR HARD BACK (£49.95) or a ECONOMY (£9.99) SOFTBACK black and white VERSION – it is also available as a KINDLE (£2.99) book. For further information about our work on Prehistoric Britain visit our WEBSITE or VIDEO CHANNEL.

Product details

- ASIN : B0BQG7G6CJ

- Publisher : Independently published (24 Nov. 2022)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 443 pages

- ISBN-13 : 979-8370198236

- Dimensions : 15.24 x 3.33 x 22.86 cm

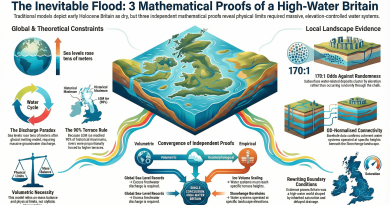

- Illustrations: 350+

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE or on our PRESS RELEASE PAGE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.