The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

Contents

Introduction

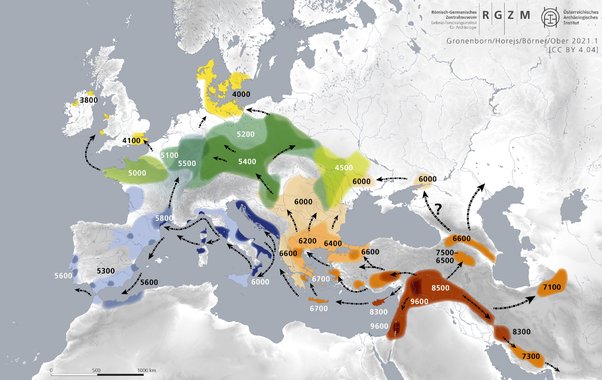

We are all well-acquainted with the conventional narrative depicting the migration journey from Asia Minor to Britain, a tale spanning millennia where settlers traversed on foot, carrying with them cultural tools and artefacts, as a seemingly seamless diffusion of humanity. However, this narrative, appealing in its simplicity, is, to put it frankly, devoid of merit. Migration patterns are intricate and resist such straightforward categorisations.

This weeks essay we look at the Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax that suggests that natural migration moved from the Countries of Asia Minor to britain over many millenium.

The unfortunate consequence of clinging to this oversimplified notion is the considerable predicament it poses for contemporary archaeologists and historians. The bulk of our historical understanding hinges on this flawed premise, creating a substantial hurdle for those seeking to uncover the complexities of our past. This misguided historical perspective, ingrained in the public consciousness through the educational system, becomes a barrier that stifles the emergence of discoveries and ideas. In the twenty-first century, breaking free from these antiquated concepts is essential for the flourishing of innovative perspectives that can contribute to a more accurate understanding of our shared history.

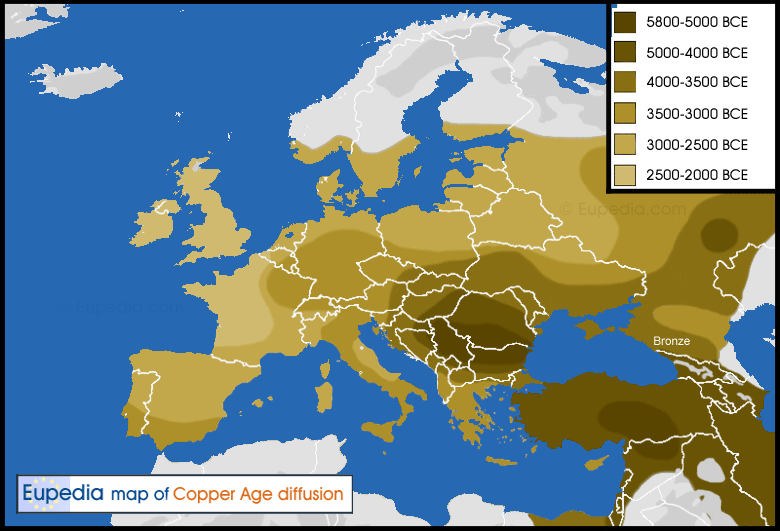

Presently, we grapple with notions suggesting that pivotal inventions like farming and groundbreaking discoveries, such as the advent of bronze, originated in the region of Asian Minor. The prevailing belief is that the transmission of such knowledge occurred exclusively through the gradual, communal diffusion of these ideas, as communities traversed vast distances over the course of millennia. However, this perspective overlooks a crucial realisation—that basic technology could have significantly augmented communication.

Old Dated Concepts

Regrettably, many academics remain ensnared by this simplistic model, shaping their mindset when unearthing artefacts in distant lands like Britain. The consequence is a tendency to either conceal evidence that contradicts this established model or dismiss such findings as anomalies that deviate from the conventional narrative perpetuated in universities. By acknowledging the potential role of enhanced communication technologies, we open the door to a more nuanced understanding of the past, unshackling ourselves from the constraints of an outdated and overly simplistic historical framework.

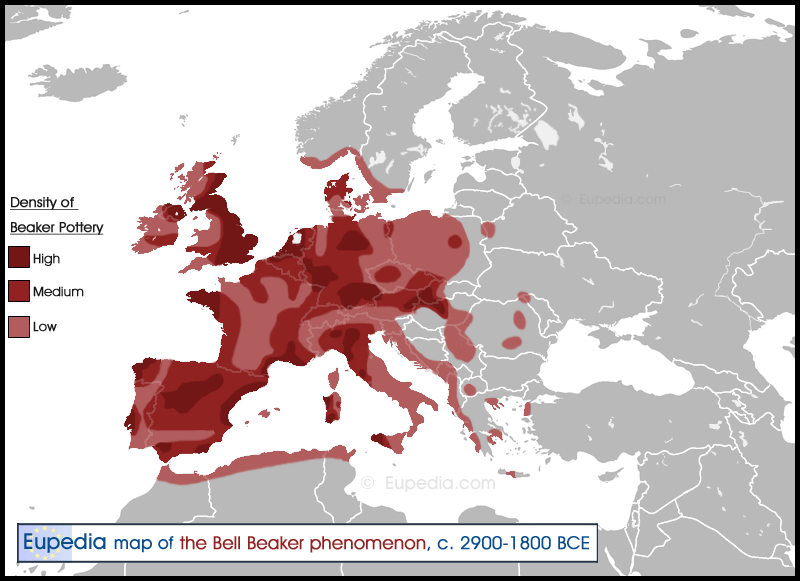

The oversimplified hypothesis becomes particularly evident in the narrative surrounding the ‘Beaker’ civilization. According to the prevailing account, the Beaker folk, inhabitants of the Late Neolithic–Early Bronze Age around 4,500 years ago in the temperate zones of Europe, derived their name from the distinctive bell-shaped beakers they crafted, adorned with finely toothed stamps. Often referred to as the Bell-Beaker culture, these people were described as warlike, primarily bowmen armed with copper weapons and engaged in an extensive search for copper and gold, which purportedly hastened the spread of bronze metallurgy in Europe. The narrative suggests that, originally from Spain, the Beaker folk rapidly expanded into central and western Europe in pursuit of metals.

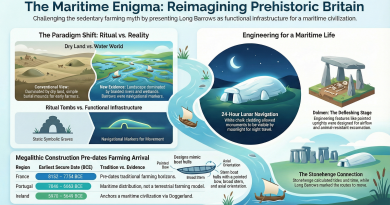

This portrayal, however, overlooks a critical aspect – the availability of boats for travel among these Europeans. The impracticality of traversing from mainland Europe to Britain on foot underscores the importance of maritime transport. Consequently, these communities likely had the means to trade their wares well before any migration occurred, with the movement of people potentially emerging as a byproduct of their established trading activities. Failing to acknowledge the role of seafaring capabilities obscures a more comprehensive understanding of the dynamics at play during this period.

New World Migration Patterns

Indeed, the historical model of the European colonisation of America in the 17th century serves as a compelling and often overlooked example that challenges the dated perspectives on migration. This empirical evidence, rooted in written history, sheds light on the dynamics of movement and colonisation, showcasing the pivotal role of boats (or in the case of America carts) in facilitating such endeavours.

As highlighted by historical records, early colonists from European kingdoms with well-developed military, naval, governmental, and entrepreneurial capabilities embarked on the colonisation of the New World. The Spanish and Portuguese, drawing on centuries of experience in conquest and colonisation, leveraged their expertise gained during the Reconquista and navigational skills for oceanic voyages. The English, French, and Dutch, while possessing the ability to build ocean-worthy ships, lacked the extensive history of colonisation exhibited by Portugal and Spain. Nevertheless, English entrepreneurs established colonies with a foundation of merchant-based investment that required less government support.

This historical example underscores a critical point often overlooked in the study of migration — the motivations behind the movement of people. In this context, the colonisation of the New World was primarily driven by economic interests, power, and the pursuit of wealth. Failure to recognize these underlying motives represents an anthropological flaw in our historical narratives, which often simplify migration as a mere expansion into new territories. Understanding that migration involves significant time, effort, and resources challenges the notion that people move solely to find new lands to occupy. The fact that the population was relatively small at the time suggests that land occupation was more of a choice than a necessity, further emphasising the complex motivations behind human migration.

American Colonies

The spread of American colonies from just the east coast to the west shows the motivation factor behind migration coast. Here are some key reasons:

Land Availability: As European settlers arrived on the East Coast, they quickly realized that the region had limited arable land and was becoming crowded. The allure of available land in the western territories motivated people to move westward in search of better opportunities.

Economic Opportunities: The promise of economic opportunities, such as fertile land for farming and the discovery of valuable resources like gold and silver, attracted many individuals and families to move west. The prospect of acquiring land for farming and starting anew was a powerful motivator.

Technological Advances: Improvements in transportation, such as the development of canals, roads, and later the railroad, made it easier for people to travel and settle in the western territories. These advancements reduced the challenges associated with long-distance migration.

Government Incentives: The U.S. government actively encouraged westward expansion through policies such as the Homestead Act of 1862, which provided 160 acres of public land to settlers for a small fee, provided they improved the land by building a dwelling and cultivating crops. This attracted many settlers to the frontier.

Escape from Economic Hardship: Some individuals moved west in the hope of escaping economic hardships or seeking a fresh start. This was particularly true during times of economic downturns or regional crises on the East Coast.

As I explore historical narratives, the distribution of populations from east to west in America emerges as a series of sudden leaps rather than a gradual process. Take, for instance, the bold leap made by the East Coast New England colonies during the California Gold Rush. Over just seven years, there was an astonishing migration of 3,232 miles—a journey equivalent to the distance from Asia Minor to Britain, a span traditionally believed to have taken four thousand years.

This leap of faith was driven by reports of gold in California, sparking a massive upheaval as individuals sought to capitalise on the potential wealth. The allure of prosperity motivated people to traverse the vast expanse of the continent, reflecting how specific events and opportunities could swiftly reshape population distribution.

Asian Wheat in the Solent

This intriguing phenomenon prompts me to reevaluate traditional timelines considering recent archaeological discoveries. For example, the presence of an 8,000-year-old boat in the Solent with wheat on board challenges established notions. Wheat, believed to have been introduced to Britain much later, now questions the pace of historical movements and interactions. It’s a reminder that our understanding of history is dynamic, subject to revision as new evidence emerges, and that the narrative of human migration is filled with unexpected leaps and transformative moments.

As someone who has delved into the pages of history, it’s clear that the driving force behind human movement has consistently been the pursuit of prosperity. This very motivation underscores the crucial role that trading played in prehistoric times. Individuals displayed a willingness to traverse great distances in search of the abundant rewards that relocating, whether to America or prehistoric Britain, could offer. Contrary to some contemporary perceptions, the gradual dissemination of cultures and technology wasn’t as linear as we might currently believe.

In reflecting on the past, it becomes evident that the motivation to seek better economic opportunities was a shared aspect of the human experience. The narrative of the slow, methodical spread of cultures and technology was not a conscious effort but rather a consequence of our collective pursuit of better circumstances. The archaeological evidence at our disposal today strongly supports the notion that the exchange of ideas and trading materials occurred in tandem, almost synchronously, across the landscapes of Europe. It’s through this lens of trading ideology that we can better understand the interconnected and dynamic nature of our historical journey.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?