Section L – NY76NE

Contents

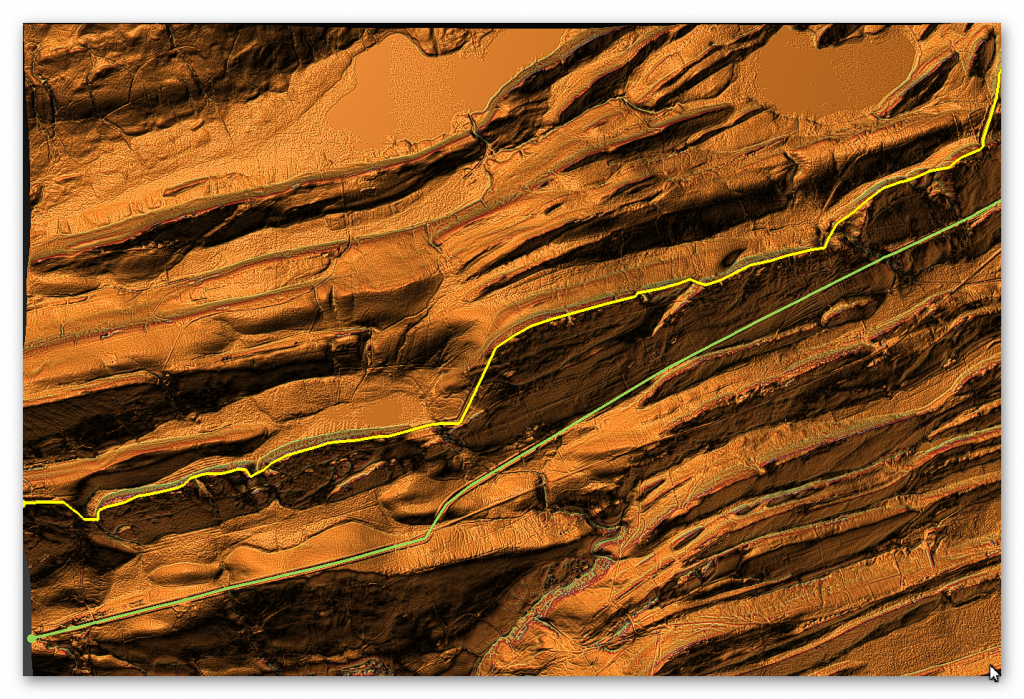

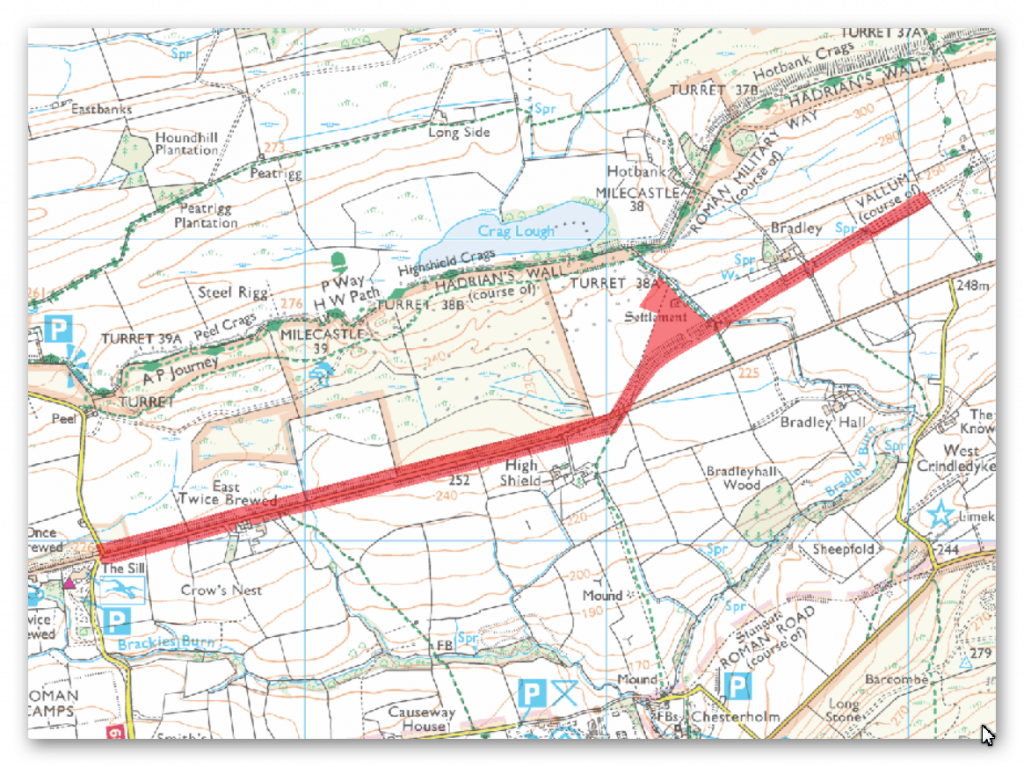

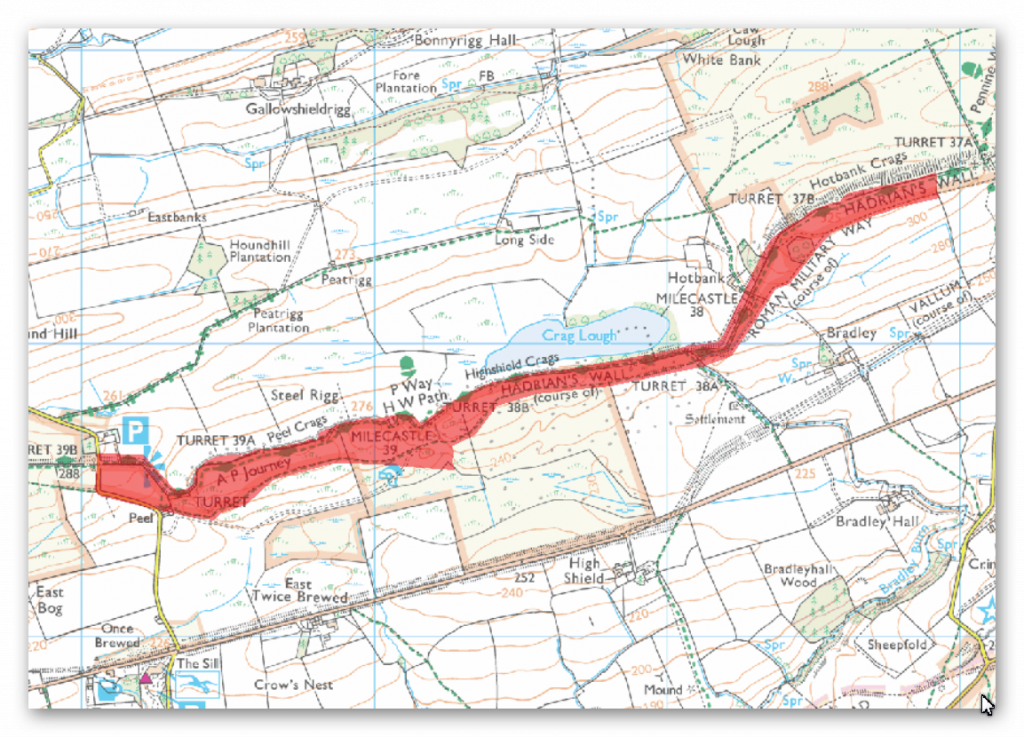

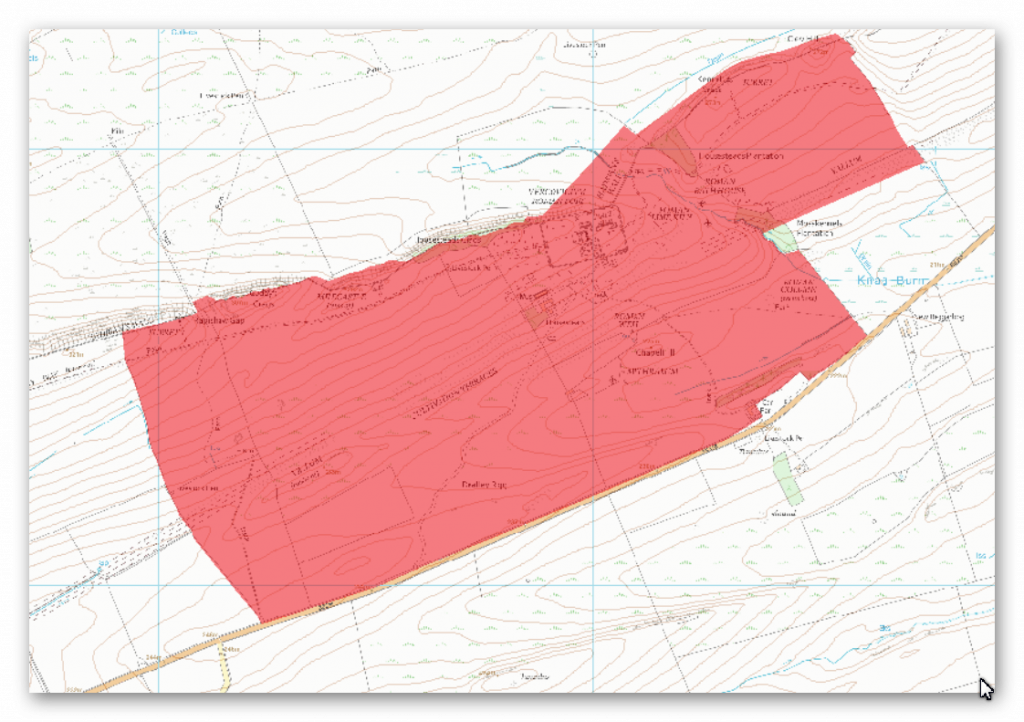

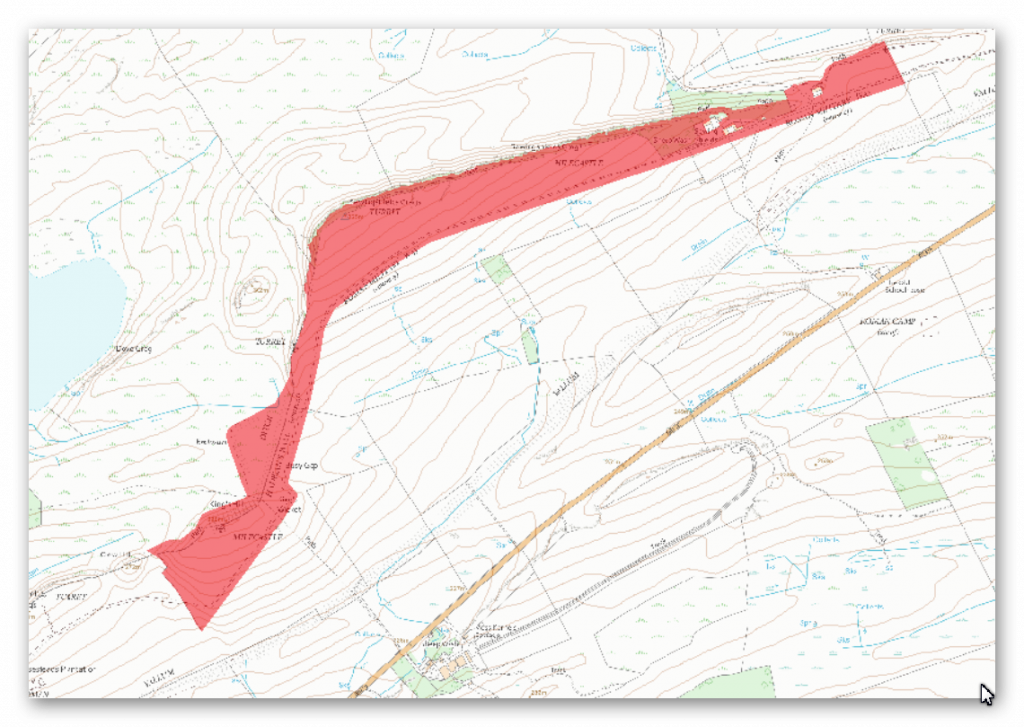

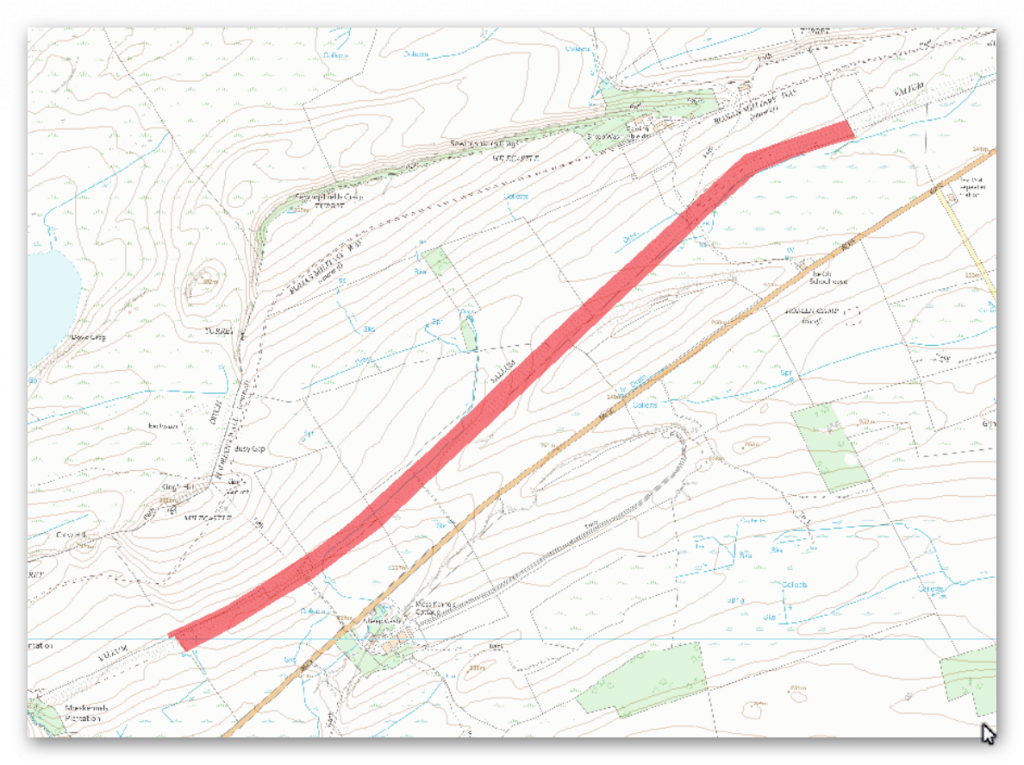

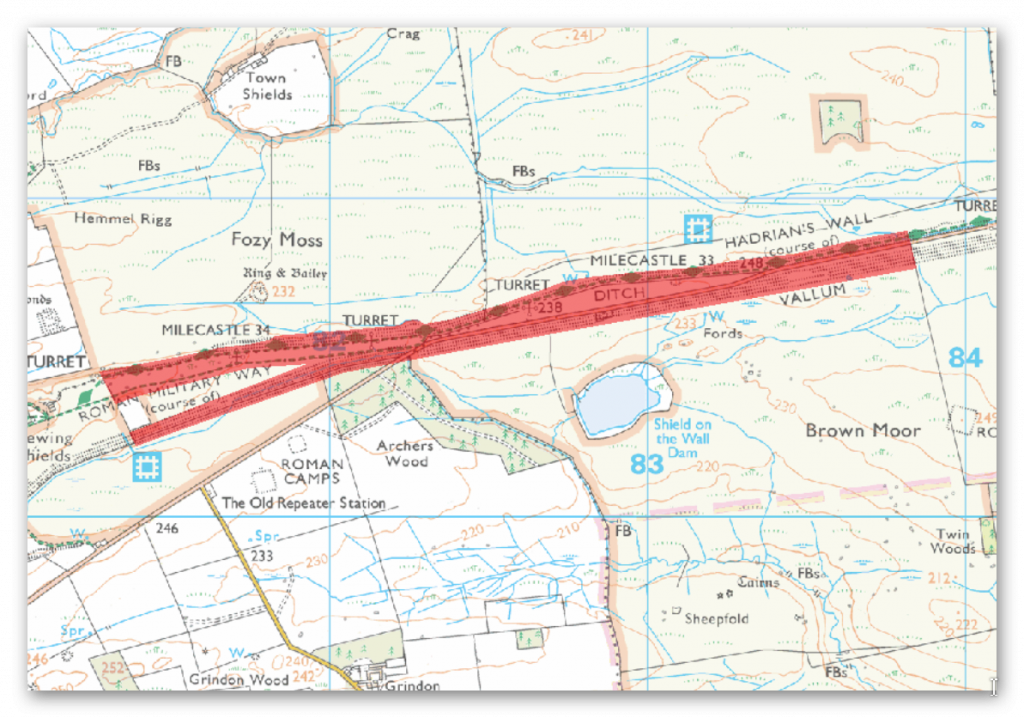

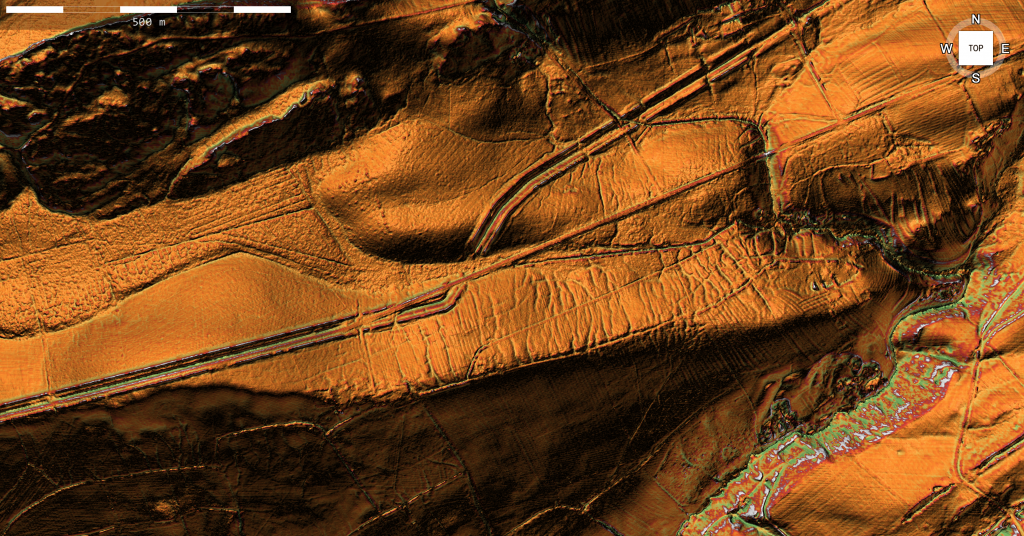

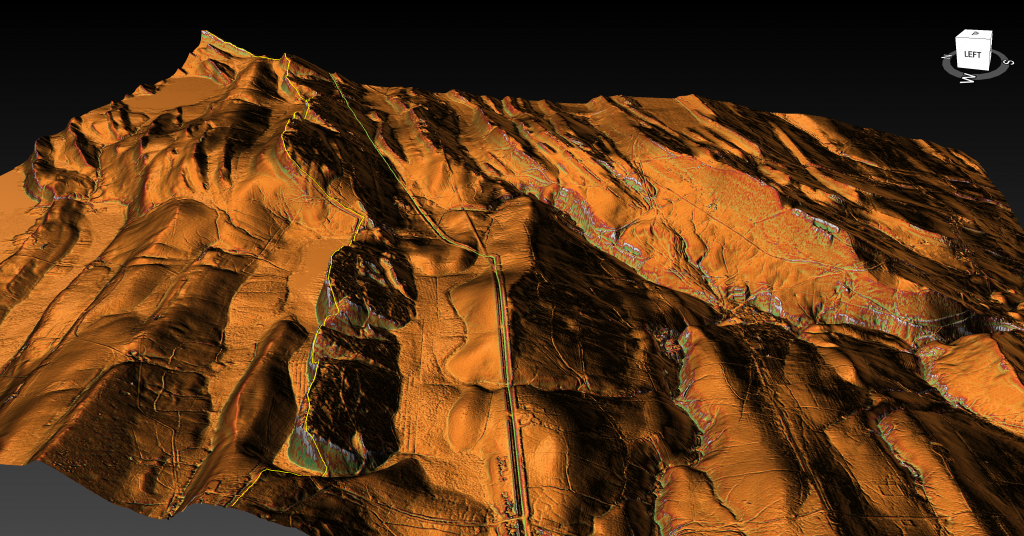

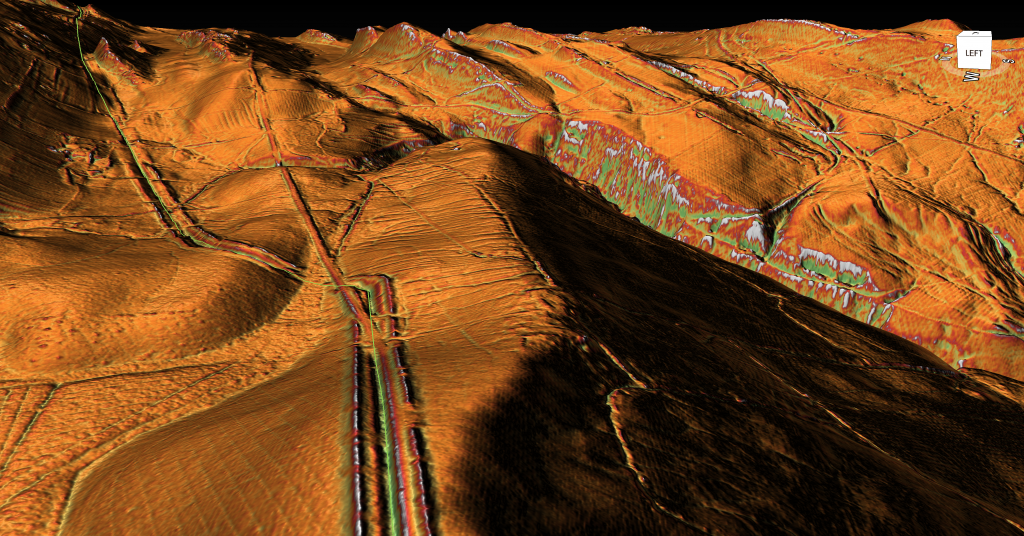

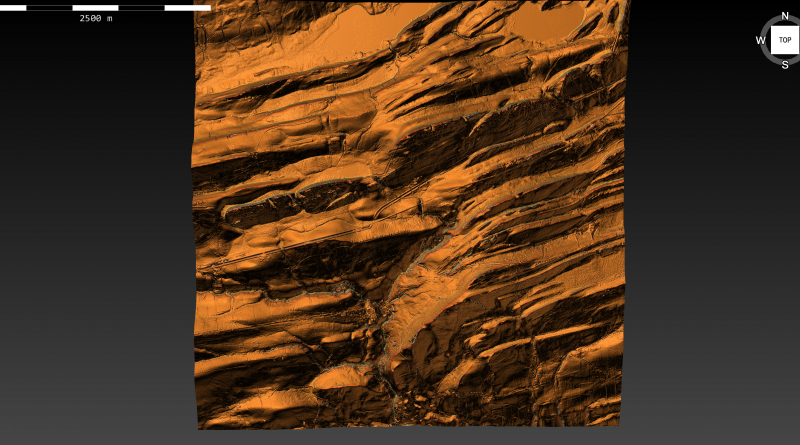

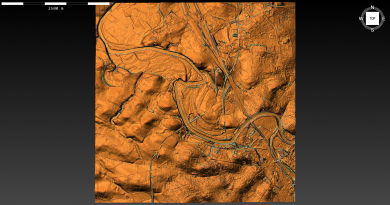

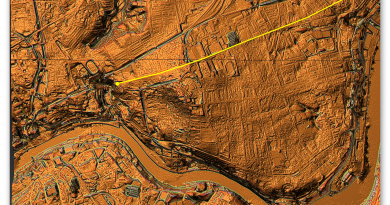

Section L – NY76NE – this is a section of Hadrian’s Wall showing the LiDAR, Google Earth and 1800 Maps of the Area covered by Historic England

Historic England Sections:

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and associated features between vallum between the field boundary at Brown Dikes to Steel Rigg car park in wall miles 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38 and 39

List UID:1010972, 1010966, 1018585, 1010964, 1010965, 1010963

Old OS Map

LiDAR Map

Google Earth Map

Historic England Scheduled Monuments within Section L

Name: The vallum and a British settlement between the field boundary west of turret 37a and the road to Steel Rigg car park, in wall miles 37, 38 and 39

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010972

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and associated features between the field boundary west of turret 37a and the road to Steel Rigg car park in wall miles 37, 38 and 39

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010966

Name: Housesteads fort, section of Wall and vallum between the field boundary west of milecastle 36 and the field boundary west of turret 37a in wall miles 36 and 37

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1018585

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and associated features between the boundary east of turret 34a and the field boundary west of milecastle 36 in wall miles 34, 35 and 36

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010964

Name: The vallum and early Roman road between the field boundary east of turret 34a and the field boundary west of milecastle 36 in wall miles 34, 35 and 36

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010965

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between the field boundary at Brown Dikes and the field boundary east of turret 34a in wall miles 32, 33 and 34

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010963

The monument includes the section of vallum and the Milking Gap native British settlement between the field boundary west of turret 37a in the east and the road to Steel Rigg car park in the west.

The vallum survives well as an upstanding earthwork throughout most of this section. Where extant the north mound averages 1.7m high, the south mound 1m high and the ditch 1.2m deep. Between High Shield and Twice Brewed the B6318 road overlies parts of the vallum. However, where it runs along the line of the vallum the road lies on the south berm, which has resulted in some disturbance to the monument. To the south of Hotbank Crags the remains of the vallum have been reduced and the ditch silted up, though its course can still be traced.

A native British settlement is situated on the west side of Milking Gap between Hadrian’s Wall and the vallum. It is located in a dip on the springline at the base of the slope to the south of Hotbank Crags. It survives as a series of upstanding stone remains and buried features. The settlement itself includes a rectilinear enclosure which has been subdivided around a central stone hut which has an entrance in its east side. The enclosure walls are made with double faced boulders and average 2m wide and 0.8m high. The central hut has a diameter of 7m and has internally faced walls 1.3m wide and 0.4m high. The remains of other huts survive to the south and east of the central hut with walls less than 1m wide and 0.25m high. Excavation in 1937 by Kilbride-Jones discovered pottery which showed that the settlement was occupied during the second century AD. Around the settlement are a number of low mounds and cairns which may be contemporary or earlier. These average between 0.2m and 0.5m high. Fragmentary remains of walls around the site are probably the remains of an associated field system. These walls are made from boulders and average 1.2m wide and 0.4m high.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and its associated features between the field boundary west of turret 37a in the east and the west side of the road to Steel Rigg car park in the west. Hadrian’s Wall follows the crest of the Whin Sill throughout this section, which includes the steep rock outcrops of Hotbank Crags, Highshield Crags and Peel Crags. There are extensive views to north and south all along this section. The upstanding remains of Hadrian’s Wall, the milecastles and turrets are Listed Grade I, from Milking Gap to the road to Steel Rigg car park.

Hadrian’s Wall survives well as an exposed and consolidated wall for the larger part this section averaging 2m wide and 1.4m high. It reaches a maximum height of 2.75m at Sycamore Gap where there are 11 courses extant. Here there are also traces of original mortar and whitewash along the north face and in the wall core. Above Sycamore Gap on its west side is a section of bypassed broad wall foundations which measure 2.75m wide and two courses high on the east side and a single course high on the west side and is now consolidated and on display. Above Peel Crags the Wall is in poor condition though it stands up to 2.7m on its north side and up to 1.7m on the south side. Elsewhere in this section the Wall survives as a turf-covered mound averaging 2m wide and 1m high. Modern field walls overlie these turf-covered stretches of Wall. The wall ditch was only constructed in the gaps between the crags, as the steep craggy scarps render a ditch superfluous here. Where it was constructed the ditch survives as a visible feature. At Milking Gap the ditch averages 10m wide and 1m deep. Excavations by Crow in 1986 to the west of the Roman tower at Peel Gap showed the ditch to be 9m wide and 2.3m deep with a level berm 9.5m across. At Peel Gap the ditch is less well preserved as a surface feature, though it averages 1m in depth. The ditch upcast mound, usually known as the `glacis’, is here visible only as a slight counterscarp.

The glacis is better preserved at Milking Gap where it averages 6m wide. Milecastle 38 is situated on a west facing slope with views to the north and south. It is visible as a series of turf-covered mounds and it measures 18m north east to south west by 17.4m across. The turf-covered remains of the north east wall are 2.6m wide and 1.2m high. On the south and east sides robber trenches mark where the walls were located. These measure 3.6m wide and up to 1.4m deep. There are traces of a rectangular building in the south west corner. The milecastle was partly excavated during 1935 by Simpson. Pottery found indicated occupation continued into the fourth century AD. Milecastle 39, known as Castle Nick, is positioned in a steep sided gap between Highshield Crags and Peel Crags with views to the north and south. It survives well as an upstanding stone feature and is now consolidated. It measures 19m long and about 15.5m across, though its overall width varies slightly at each end. The walls stand up to 1.75m high. The milecastle was partly excavated by Clayton and later by Simpson. However, excavations by Crow between 1985 and 1987 produced a detailed understanding of the milecastle and its internal structures and their development over time. Early barrack blocks were later replaced by individual small buildings with curved porches, probably designed as wind breaks. The pottery sequence showed that the occupation of the milecastle was continuous and ended probably sometime in the fourth century AD. An 18th century milking parlour was later constructed in the north west part of the milecastle.

The milecastle excavation produced many small finds including pottery, coins, and metalwork which included short swords and lances, together with gaming boards and pieces. Turret 37b is located on the crest of Hotbank Crags with very extensive views in all directions. It survives as a turf-covered platform. The platform measures 6.3m north to south and 10m across and is up to 1.4m high. There is a small enclosure on the east side of the platform which appears to abut both the south side of the Wall and the east side of the turret wall. It could therefore be contemporary with the Wall and may have served as a small stable. It was located in 1911 by Simpson. Turret 38a is located on the west side of Milking Gap on an east facing slope. It commands extensive views to the south and directly overlooks Crag Lough to the north. It survives as a buried feature below the turf. It was located in 1911 by Simpson. Turret 38b is located on Highshield Crags and also has extensive views in all directions. It survives as a turf-covered platform. The platform measures 6.8m north to south and 13.4m across. There is an internal scarp up to 0.3m high. This turret was also located by Simpson in 1911.

Turret 39a is located on the crest of Peel Crags and commands wide views in all directions. It is visible as a slight rectangular hollow about 0.2m deep. The turret was located in 1909 and excavated in 1911 by Simpson. Its walls were of narrow gauge and were found to have been demolished and the Wall built over its entrance indicating that it fell out of use during the Roman period. A platform, probably for a ladder, was positioned in the south west corner. The remains of a man and a woman were found buried in the north west corner. Burial in such a place was against Roman law and as such these could be the remains of an unlawful event. A Roman tower is positioned in Peel Gap on Hadrian’s Wall with limited views to the north and south. Unusually it is located between the two turrets 39a and 39b. It survives as consolidated stone foundations. It was discovered by Crow during investigation and clearance of the Wall in this section in 1986. This additional tower was later than the Hadrianic narrow wall. Finds from inside and outside the tower showed that it had a similar structural history and use to the neighbouring turrets. Hearths and a ladder platform were found in the interior. Wall mile 39 is a particularly long one as the distance between turrets 39a and 39b exceeds by over 200m the normal spacing of 494m from turret to turret.

The Peel Gap tower lies exactly midway between these turrets implying that spacing was the most important factor determining its location. As an observation post it is in a very poor position. A medieval tower is located in Peel Gap abutting Hadrian’s Wall. It was probably part of the original pele tower which gave its name to the modern farmhouse and adjacent crag. It survives as a slight platform with excavation trenches and spoil heaps, up to 0.4m high. It was excavated by Simpson in 1911 who recovered medieval green glazed pottery from the interior. The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, survives well as a linear causeway throughout this section. Some stone is visible on the south scarp where it has been built up to make a level surface. This scarp appears to have had a stone revetment. The south scarp averages 0.4m in height, although it reaches up to 1.2m high in places. West of Peel Farm the Military Way is overlain by the road to Steel Rigg car park.

To the south of Sycamore Gap are the remains of a prehistoric field boundary running roughly from north to south, probably dating to the Bronze Age. The Roman Military Way overlies this boundary which indicates that it is certainly pre-Roman in date. The peat bog, which has grown over remains of this boundary further to the south, is of Bronze Age origin. A second boundary is located running transversely to the Sycamore Gap boundary, to the west of it, south of the Military Way. Their assumed junction is masked by the peat bog which has built up to the south. These boundaries survive as sinuous linear features of low stone banks, averaging 1.2m wide and 0.5m high. A small irregular field system is situated to the south of milecastle 39. It takes the form of two roughly rectangular paddocks linked by an axial boundary. The boundaries survive as upstanding features. They are constructed from roughly coursed boulders standing up to 1m wide and 0.45m high. They are of a form usually considered to be medieval.

The axial boundary runs up to the south east corner of the milecastle showing that it is later than the milecastle in date. There are ten shielings located within this section of the Wall. Shielings are small shepherds’ huts which were used on a seasonal basis usually during upland grazing in the summer months. They are characteristic of the medieval period in this area. There are five free standing shielings located between Castle Nick and Sycamore Gap. Their dry stone walls average 1m in width and 0.4m high. A group of three shielings with multiple phases are located 50m east of milecastle 39 abutting the south face of Hadrian’s Wall. These were discovered during excavations between 1985 and 1987 by Crow. Their walls average 0.6m wide and 0.4m high. They are now consolidated and are visible as stone features. Two further shielings are situated 120m east of turret 38a. They survive as low stone structures and are situated to the immediate south of Hadrian’s Wall. The largest and easternmost of the two measures 9m by 3m with traces of an entrance in its south wall. The walls of both shielings stand up to 0.3m high. On either side of the last pair of shielings is an irregular enclosure abutting the south face of Hadrian’s Wall. They survive as upstanding stone features.

The larger and westernmost of the two enclosures measures 28m east to west by 5m wide. Its walls are constructed from roughly coursed boulders which stand up to 0.4m high. The much smaller enclosure to the east also has walls made from roughly coursed boulders up to 1.5m wide and 0.4m high. Both of these features are probably shielings or animal byres, although their irregular form is unusual. All field boundaries, except those constructed directly on the line of Hadrian’s Wall, sign posts, stiles and road/trackways are excluded from the scheduling, but the ground beneath all these features is included.

The monument includes Housesteads Roman fort and the section of Hadrian’s Wall and vallum and their associated features between the field boundary west of milecastle 36 in the east and the field boundary west of turret 37a in the west. This section occupies the crest and down slope of the escarpment, defined to the north by Housesteads Crags and Cuddy’s Crags and to the south by the B6318 road.

Throughout most of this section Hadrian’s Wall survives as an upstanding feature. To the east of the fort a 320m section of the Wall is consolidated and in the care of the Secretary of State. Within this stretch of consolidated Wall there is a gateway, 3.7m wide, at the low point of the Knag Burn. Possibly used by civil rather than military traffic, it consists of a single passage flanked by guard chambers on either side. Pivot holes at back and front show that there were two sets of doors. Between milecastle 36 and the stretch of consolidated Wall, the Wall survives as a turf-covered mound overlain on its north face by a modern field wall made from reused Roman masonry. West of Housesteads to Rapishaw Gap the well-preserved remains of the Wall have been consolidated. At Rapishaw Gap itself the Wall has been mostly robbed out and a modern field wall overlies its south face. Beyond Rapishaw Gap the Wall again survives as a consolidated upstanding feature.

The wall ditch was only constructed in the short gaps between the steep crags. On Clew Hill the 35m section of ditch is up to 13m wide and 2m deep with tumbled Roman masonry from the Wall in its base. Between Housesteads Crags and Cuddy’s Crags the ditch is visible though it is prone to silting and water-logging. Possible remains of the ditch upcast, known as the `glacis’, survives to the north of the ditch as an amorphous spread of material covered by turf. At Rapishaw Gap the ditch is heavily silted and overgrown with rushes, though it is still visible to a depth of 1.3m. A modern trackway truncates the west end of this ditch. To the north east of Housesteads fort, and at the foot of the crags on which the Wall is located, a number of medieval shielings have been identified. These were used seasonally by shepherds controlling summer grazing on open lands to the north.

Additionally a linear earthwork, identified as a prehistoric field boundary has been identified as well as Roman quarries. Two circular earthworks, one known as the Fairy Stones, may be of prehistoric or medieval date, although their function is not yet fully understood.

Milecastle 37 is situated on the crest of Housesteads Crags with extensive views to the north and south. It is visible as an upstanding structure which has been partly reconstructed and consolidated. The walls have a maximum height of 2.2m internally and the single barrack block in the east half survives to 1m in height. The milecastle was partly excavated between 1988 and 1989 by Crow when it was shown that the north gateway of this milecastle had been deliberately blocked and then later partly demolished. Turret 36a, located in 1911, occupies the crest of Kennel Crags. It is visible as an irregular turf-covered platform measuring 17m north east by 6m south west, and up to 1.1m high. No internal features are visible and it is partly overlain by stone which has tumbled onto it from the adjacent Wall. Excavations during 1946 showed that the turret had narrow walls and a door in the east side.

Turret 36b was built before Housesteads fort, occupying part of the crest of Housesteads Crags later overlain by the fort. The foundation courses of the turret have been exposed by excavations within Housesteads fort. It survives as an upstanding structure which has been consolidated and is in the care of the Secretary of State as part of the fort. Turret 37a was located on the crest of the scarp on the west side of Rapishaw Gap. It survives as a buried feature beneath a turf cover. The turret was deliberately demolished in an early phase and the Wall was rebuilt across the site.

The Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, survives as a turf-covered linear mound throughout most of this section. West of Housesteads Plantation the mound is well-preserved, up to 6.6m wide in places. East of Housesteads Plantation the mound is 4m wide and 0.8m high on its south side. The Military Way crosses the Knag Burn by a double dog-leg and enters the east gate of the fort between the buildings of the extra mural settlement. West of the fort the Military Way is visible as a linear mound with an often indistinct north side. It averages between 3.3m and 6m in width.

The south side is revetted by a line of boulders up to 0.6m high. The road is turf- covered with some cobbling visible in places. The approach to the west gate of the fort is blocked by two or three banks which seem to be late defences of the fourth century AD. Branch roads leading from the Military Way proper to turret 36a, milecastle 37 and turret 37a are visible in places as slight level mounds. Elsewhere their course is indicated by differing vegetation marks seen in grass colour. This differentiation in vegetation cover reflects differing growing conditions on the compacted road surface. An earlier Roman road runs from the north side of the vallum south of King’s Hill westwards towards Housesteads where it is overlain by the Military Way at NY7925 6997. It survives as a turf-covered linear mound up to 6.5m wide and 0.9m high. Some metalling is visible through the turf. East of the fort the vallum survives as an upstanding earthwork. The north and south mounds have been reduced and spread by agriculture, though the ditch is up to 1.5m deep. West of the Knag Burn there is little surface trace of the vallum as it was levelled when the settlement outside the fort developed and was built over it. To the west of the fort the remains of the vallum are not obvious. However, parallel cultivation terraces and occasional banks up to 1m high denote its course. The ditch is completely silted up in this stretch.

The Roman fort at Housesteads, known to the Romans as Vercovicium, occupies the prominent crest of the Whin Sill escarpment to the west of the Knag Burn. It commands wide views to the north and south, being one of the most dramatic and best preserved Roman sites in Britain. It is unusual among the Wall forts for having an east-west orientation rather than a north-south one. This is due to the constraints imposed by the topography.

The fort covers an area of approximately 2ha and accommodated a cohort between 800 and 1,000 strong, being later reinforced by a cavalry unit. Its remains survive well as upstanding masonry and earthworks and buried features. The walls and gateways of the fort are exposed and consolidated. A number of the interior buildings are also exposed and consolidated including the headquarters building, the commanding officer’s house, a hospital, granaries, barracks, workshops and a latrine. The fort is in the care of the Secretary of State. The fort was added to the Wall after the broad wall foundations and turret 36b were built, but before the narrow wall (which was eventually constructed on the broad wall foundations) was constructed up to the fort. The earliest activity on the site is evidenced by a Bronze Age pot found beneath one of the barracks, which had probably come from a ridge top burial cairn. Post-Roman activity on the fort site is evidenced by a bastle house which was built partly over the west tower of the south gateway.

There has been a history of excavations on the fort from 1822 up to 1988. The civil settlement outside the fort, usually referred to as a vicus, is very extensive stretching for at least 200m south of the fort. It also clustered around the east and west sides of the fort. In its initial phase the vicus was situated to the south of the vallum. However, by the third century AD at the latest the vallum was levelled and the vicus was moved up the hill and constructed immediately adjacent to the fort. To the south of the fort over 20 buildings were excavated during the 1930s, although only six remain on view as upstanding buildings with consolidated stone walls. They are believed to be the foundations of a group of shops and/or taverns. Outside the fort’s east gate small robber trenches demarcate the ground plans of some of the vicus buildings. On the west side of the fort, north of the Military Way, there is a series of mounds, up to 0.8m high, forming small rectangular paddocks. These may have accommodated the horses associated with the cavalry unit known to have been stationed at the fort in its later phases. Aerial photographs show that the remains of the vicus around Housesteads covered an area at least as large as that of the fort itself. Excavation has shown that the settlement dates, in its most developed form, to the third and fourth centuries AD. An inscription indicates that this vicus had its own local government.

Beyond the vicus to the south and west there is a series of cultivation terraces running along the contours in a roughly east-west direction. They survive as upstanding earthworks and can be seen to directly overlie the vallum. These terraces are themselves overlain in parts by strip fields and early ridge and furrow cultivation. On the basis of these relationships the terraces are considered to be of Roman date and are probably associated with the vicus settlement. The Housesteads bath house was positioned to the east of the fort on a rock shelf on the slope on the east side of the Knag Burn. Its disturbed remains survive as turf-covered undulations. Investigations have shown that it was heated by hypocausts, soot being found in the flues. Nearer the Wall is a spring cased in Roman masonry, which probably supplied the baths with water. The location of two cemeteries at Housesteads fort and vicus are known, surviving as buried features below the turf cover. There is one cemetery situated to the west of the fort, south of the Military Way. Another is known to lie either side of Chapel Hill. To the south of Chapel Hill a number of tombstones have been found including one commemorating a medical officer named Anicius Ingenuus. In the low ground to the east of Chapel Hill human remains have been found during drainage works. These finds suggest the cemetery around Chapel Hill was extensive.

The remains of a temple to the Persian god Mithras is located beyond the west end of Chapel Hill, close to where a spring flows. This half underground temple was located in 1822. It survives as a series of turf-covered features, some of which are visible as slight earthworks. Excavations in 1898 revealed a long nave, flanked on either side by benches for the accommodation of worshippers. Beyond this was the sanctuary which contained an elaborate relief carving of Mithras surrounded by the zodiac, together with several altars and statues to two lesser deities. The remains of a temple to the Germanic god `Mars Thincsus’ is located to the north of Chapel Hill. A well found during excavation has been consolidated and can be seen on the ground. The other remains survive as buried features. Excavations during 1961 revealed the foundations of a circular shrine, 4m in diameter. Pottery recovered from the interior dated the structure to the third century AD. Other finds included an elaborately carved arched door head and inscribed stones dedicated to `Mars Thincsus’. The shrine was found to overlie part of the vicus settlement when it was situated to the south of the vallum. A series of temples are known from building inscriptions to have been located on Chapel Hill itself. Their remains survive as buried features. Several altars have been found here dedicated to Jupiter and the Spirit of the Deified Emperors, indicating that the official state cult was practised here.

A Roman lime kiln is located on the west side of the Knag Burn near to the bath house. It was located and excavated during 1909 by Simpson. Its remains survive as buried features. Pottery from the interior dated the structure from the late third to the mid-fourth century AD. A bastle house was built over the remains of the east side of the south gateway of the fort in the 16th century. It survives as an upstanding stone feature, rebuilt with Roman masonry and projects out to the south of the fort. Bastle houses are defended farmhouses, usually with an upstairs doorway and no windows in the lower storey. The upper stories were lived in while the lower one was used as an animal byre. Bastle houses often occur in small groups and are characteristic of the 16th and early 17th century, being a response to the cattle raiding exploits of the border reivers.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and its associated features between the field boundary east of turret 34a in the east and the field boundary west of milecastle 36 in the west. This section of the Wall occupies the crest and slopes along Sewingshields Crags.

The upstanding remains of Hadrian’s Wall, the milecastle and turrets are Listed Grade I, from turret 34a to turret 35a. The Wall survives intermittently as an upstanding feature throughout this section. West of milecastle 35 the Wall survives as an irregular turf-covered mound, averaging 2.5m wide and 0.6m high. Either side of milecastle 35 the remains of the Wall are upstanding and have been consolidated. At 2.3m wide it is of narrow wall type, though it has been set on a broad wall foundation, 3m wide. It stands to a maximum height of 1.5m. Along the crest of Sewingshields Crags the upstanding sections of consolidated Wall are divided by sections of the Wall which survive as turf-covered mounds, averaging 2.5m wide and 1m high.

Where the Wall changes direction to a north-south alignment it survives as a buried feature beneath a modern field wall made from reused Roman masonry. This field wall overlies the north face of the Wall. The nearly 3km of Wall around Sewing Shields farm is in the care of the Secretary of State. For most of this section there is no outer ditch, as the Wall occupies the crest of the steep outcropping bedrock of Sewingshields Crags and a rock cut ditch would have been superfluous. At Busy Gap a section of ditch was cut which survives as a feature, 12m wide and up to 1.2m deep. West of milecastle 36 another shorter section of ditch was cut, now measuring 2.1m in depth and 10m in width. To the north of the Wall, at the foot of Kings Hill crags is a narrow linear earthwork, up to 7m wide which has been identified as a prehistoric field boundary. Milecastle 35 is located on the east facing slope of Sewingshields Crags. It survives as an upstanding masonry feature which has been consolidated and is now in the care of the Secretary of State. It measures 18.3m north-south by 15.2m east-west. The walls are up to 3.2m in width. Within the milecastle several phases of buildings are preserved in the ground plan.

Milecastle 36 occupies the summit of Kings Hill. It survives as a turf-covered feature. The east and west walls are indicated by robber trenches up to 0.5m deep. The featureless interior of the milecastle is overlain by stone which has tumbled onto it from the adjacent Wall. The milecastle was excavated during 1946 and was found to have narrow walls. The north gate had been reconstructed in a post-Hadrianic period, probably around AD 180. The south gate had been destroyed. The well preserved remains of turret 34a, which are in the care of the Secretary of State, are located on an east facing slope. It was located in 1912 by Simpson and was partly excavated during 1947 and 1958. The site was again excavated during 1971 for the Department of the Environment and was shown to measure 3.55m north-south by 3.9m east-west. It had a door in the east side and a possible ladder platform in the south west corner. It has narrow walls measuring 0.95m wide. Most of the pottery recovered from the turret is of second century AD date. In the medieval period the turret walls were partly reduced and the south face of Hadrian’s Wall was continued across the turret to make a continuous rampart walk. Medieval pottery sherds, were also found which suggests that the rampart walk was possibly in use at the same time as Sewingshields Castle, which lies about 150m to the north west. The exact location of turret 34b is not known with certainty as there are no surviving upstanding remains.

On the basis of the usual spacing, the turret would be expected to be located beneath the Sewing Shields farm complex. Turret 35a is located on the summit of Sewingshields Crags. It survives as an upstanding feature. The masonry has been consolidated and it is in the care of the Secretary of State. The turret was located in 1913. Excavations took place during 1947 and 1958 when it was found to have narrow walls, 1m wide, and a door in the east side, 0.95m wide. The turret was shown to have been abandoned during the Roman period, though it is not certain when. Its internal measurements are 3.7m east-west by 2.4m north-south; the walls are up to 0.75m high. Turret 35b is located to the north of Busy Gap on the west facing slope of Sewingshields Crags. It survives as a slight turf-covered platform measuring 5.5m from north west to south east by 5.5m north east to south west. Its interior is partly overlain by stone which has tumbled onto it from the adjacent Wall. The turret was located during 1913. Part excavation during 1946 showed that the turret had narrow walls and a door in the east side.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts survives as a turf-covered linear mound throughout most of this section. It is visible as a disturbed causeway averaging 5m wide with traces of a stone revetment on the south side. It was partly excavated between 1978 and 1980 when it was shown to have a damaged metalled surface 4m wide, a stone revetment on the south scarp, and to have been overlain by later roadways. Branch roads survive linking the Military Way with the south gates of both milecastles 35 and 36. At milecastle 35 the low, uneven turf-covered mound of the causeway is up to 5.5m wide and 0.2m high.

At milecastle 36 the turf- covered causeway is up to 4m wide and 0.3m high. About 20m west of turret 34a a small rectangular enclosure, visible as an upstanding earthwork, abuts the south side of the wall mound. Its internal measurements are 22m east-west by 6.5m north-south. Its walls survive up to 0.4m high and 2.5m wide with the east end apparently being open. No internal features are visible. This structure is probably the remains of a medieval shieling. Shielings were small enclosures used as seasonal stock compounds during upland grazing in the summer months. On the north west side of Busy Gap there are the remains of a triangular shaped enclosure, known as the King’s Wicket. It survives as a series of earthworks which include a turf-covered inner mound and traces of an external silted ditch. The enclosure is known to be a later feature which used the Wall line as its east side. It is considered to be early medieval in date and it has been interpreted as a drovers’ stock compound, possibly as a gathering point for sheltering stock when they were being driven off the common land and down to the lower pastures.

The monument includes the section of vallum, its associated features and an early Roman road between the field boundary east of turret 34a in the east and the field boundary west of milecastle 36 in the west. The vallum survives as a series of upstanding earthworks throughout this section. The north mound of the vallum has been reduced by pasture improvement, though it still averages 1m in height.

A number of low points in the mound throughout its course denote crossings over the vallum. The south mound averages about 1.2m in height, but in places it is overlain and partly obliterated by a modern field wall. The vallum ditch is well preserved, averaging 2m in depth. The causeway of an early Roman road is located running parallel to the vallum on its north side opposite Moss Kennels. It is visible as a turf-covered mound, averaging 8m wide and 0.4m high for approximately 400m throughout the western part of this monument.

Further east it has been reduced by ploughing and is no longer visible as an upstanding earthwork, although buried remains will survive beneath the present ground surface. It has a level surface with some of the metalling exposed.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall, vallum and their associated features between the field boundary at Brown Dikes in the east and the field boundary east of turret 34a in the west.

This section occupies a predominantly level stretch of ground, except at the west end where the Wall occupies the escarpment of the Whin Sill. The upstanding remains of Hadrian’s Wall, the milecastle and the turrets from the drain west of turret 33a to the field boundary east of turret 34a are Listed Grade I. Hadrian’s Wall survives as a series of upstanding and buried features throughout this section. It survives as a buried feature beneath the B6318 road at the east end of this section. Immediately east of milecastle 33 and beyond to the west end of this section the Wall survives either as a low turf covered bank, averaging 0.4m high, or as a series of robber trenches up to 0.4m deep. The north Wall-face west of the gateway of milecastle 33 is exposed for 16.7m. This unconsolidated stretch of upstanding wall reaches a maximum height of 1.5m. Either side of turret 33b the Wall is exposed and consolidated for a total length of 15.1m. Here the Wall measures 1.95m wide and has a maximum height of 1m.

The wall ditch and its associated upcast mound, known as the glacis, survive well in this section as a series of earthworks. In the east part of this section the ditch survives to an average depth of 3m while the glacis attains a maximum height of 2.7m in places. Beyond turret 33b the ditch is cut partly into the bedrock. It measures up to 13m in width and 2.2m in depth. The glacis here is seen intermittently as an irregular spread over the craggy scarp. Milecastle 33 at Shield on the Wall survives mostly as a turf covered platform visible on the ground. The north gateway and parts of the north wall are exposed as upstanding masonry up to 1.2m in height. Fragments of the south gateway are also exposed. It was partly excavated during 1884 by Clayton. Milecastle 34 is located within a small walled plantation about 430m east of turret 34a. It survives as a buried feature beneath the walls of the plantation and the wooded interior. It was noted by the antiquarian Horsley in this location during the 1730s. Milecastle 34 is in the care of the Secretary of State together with the length of wall, wall ditch and vallum to the east, as far as the point where the B6318 road crosses the vallum ditch. To the west of the milecastle the Wall alone is in the care of the Secretary of State to the end of this monument. The precise location of turret 32b has not yet been confirmed. However, on the basis of the usual spacing, it is expected to lie about 450m east of milecastle 33. As with turret 32b the precise location of turret 33a has not yet been identified. On the basis of the usual spacing it is expected to lie about 450m west of milecastle 33. Turret 33b survives well as an upstanding feature. It is consolidated and in the care of the Secretary of State. It was first located by Simpson in 1913. It measures 3.95m east-west by 3.9m north-south. The walls are 0.9m thick and have a maximum height of 1.1m. The entrance was at the east end of the south wall, but this was subsequently blocked. The turret was excavated during 1968 and 1970 when it was found that its occupation had ceased before the end of the second century AD. The Wall had then been rebuilt across the turret recess.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, was carried on the north mound of the vallum in the east half of this section. Its buried remains survive below grassland east of milecastle 33, until the B6318 road coincides with the north mound of the vallum where it lies below the modern road surface.

South of turret 33b the Military Way leaves the north mound of the vallum and follows a course parallel to that of the Wall. Here it survives as a distinct linear mound up to 6m wide and up to 0.3m high. The vallum survives well as an upstanding earthwork visible on the ground throughout this section. It runs roughly parallel with the line of the Wall until south of turret 33b where it turns to the south west and follows the tail of the escarpment. In the east half of this section the vallum ditch averages 3.5m in depth, while the north and south mounds average 1.5m in height.

A number of crossings are still extant here at 42m intervals. West of milecastle 33 the ditch averages 2m in depth and the north and south mounds 1.2m in height. West of turret 33b the ditch is partly rock cut and reaches a maximum depth of 2.5m.

Investigation

The Vallum in this section changes corse quite drastically which is not been pick-up by archaeologists as they is no obvious reason for the course change.

The original course of the Vallum looks like it went into the river valley – which strange also looks like the course of the other Roman feature Stanegate?

This section clear continues with the two bank alignment of the Vallum and the satelitte photo give us a good prospective of the size of the Vallum construction. We can only speculate to why the vallum become two laned after the previous sections quarry? The only logical conclusion is that the vallum had to be two way in traffic and the most effecytive way (rather the usual boats passing on the same strip) would be a lane system which would qualify the amount of material taken from this quarry in the past.

The other observation here is how modern roads have used the Vallum for transportatuion. Again it would seem logical to suggest when the Vallum finally dried up the banks were used as roads as during the centuries of canal use the ytraders would get using the routes for transporting and if a boat was no longer available then a crat would be better than nothing?

To understand the problem with Hadrian’s Walls history read our article HERE.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Pingback: Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation - Prehistoric Britain