Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

Contents

- 1 Historians seems to be comfortable about what we know about Hadrian’s Wall as a concept. They admit that we need to excavate more to find some details but the overall view of this landscape feature sits comfortably within the pages of the history book. (Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation)

- 2 Section A – NY26SW

- 3 Section B – NY26SE & NY25NE

- 4 Section C – NY35NW

- 5 Section D – NY35NE

- 6 Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- 7 Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- 8 Section G – NY56SW

- 9 Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- 10 Section I – NY66NW

- 11 Section J – NY66NE

- 12 Section K – NY76NW

- 13 Section L – NY76NE

- 14 Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- 15 Section N – NY87SE

- 16 Section O – NY97SW – NY96NW

- 17 Section P – NY96NE

- 18 Section Q – NZ06NW

- 19 Section R – NZ06NE

- 20 Section S – NZ16NW

- 21 Section T – NZ16NE

- 22 Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- 23 Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

Historians seems to be comfortable about what we know about Hadrian’s Wall as a concept. They admit that we need to excavate more to find some details but the overall view of this landscape feature sits comfortably within the pages of the history book. (Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation)

English heritage tells us in its many guidebooks that:

It’s nearly two thousand years since the Roman emperor Hadrian ordered a wall to be built across the north of Britannia following his visit to Britain in AD 122. Hadrian’s Wall is now the most famous frontier of the mighty Roman Empire. It dominated the region for around 300 years, stretching 73 miles (80 Roman miles) coast to coast from Wallsend in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west.

Once built, Hadrian’s Wall boasted 80 milecastles, numerous observation towers and 17 larger forts. Punctuating every stretch of Wall between the milecastles were two towers so that observation points were created at every third of a mile. Constructed mainly from stone and in parts initially from turf, the Wall was six metres high in places and up to three metres deep. All along the south face of the Wall, if there was no river or crag to provide extra defense, a deep ditch called the Vallum was dug. In some areas the Vallum was dug from solid rock.

Wikipedia will tell you that a bit more:

Hadrian’s Wall (Latin: Vallum Aelium), also known as the Roman Wall, Picts’ Wall, or Vallum Hadriani in Latin, is a former defensive fortification of the Roman province of Britannia, begun in AD 122 in the reign of the emperor Hadrian. Running “from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west”, the Wall covered the whole width of the island. In addition to the wall’s defensive military role, its gates may have been customs posts.

A significant portion of the wall still stands and can be followed on foot along the adjoining Hadrian’s Wall Path. The largest Roman archaeological feature in Britain, it runs a total of 73 miles (117.5 kilometres) in northern England. Regarded as a British cultural icon, Hadrian’s Wall is one of Britain’s major ancient tourist attractions. In comparison, the Antonine Wall, thought by some to be based on Hadrian’s wall. Hadrian’s Wall marked the boundary between Roman Britannia and unconquered Caledonia to the north. The wall lies entirely within England and has never formed the Anglo-Scottish border.

Dimensions

The length of the Wall was 80 Roman miles (a unit of length equivalent to about 1,620 yards or 1,480 metres), or 73 modern miles. This covered the entire width of the island, from Wallsend on the River Tyne in the east to Bowness-on-Solway in the west.

Not long after construction began on the Wall, its width was reduced from the originally planned ten feet to about eight feet, or even less depending on the terrain. As some areas were constructed of turf and timber, it would take decades for certain areas to be modified and replaced by stone.

Bede, a medieval historian, wrote the Wall to be standing at 12 feet (4 metres) high, with evidence suggesting it could have been a few feet higher at its formation.

Construction

The first evidence of not quite knowing the detail contained in building the wall is shown when the official accounts suggested it was at first ten foot wide and then reduced to eight – but why and was this for the whole 73 miles and parts were not wall but turf and a palisade.

This is revealed when EH suggest that:

Before the first plan was completed, a radical change led to the placing of forts on the wall line and down the Cumbrian coast, and the construction of an earthwork to the south.

The forts, each apparently built for a single unit and at a basic spacing of 7⅓ miles, were placed astride the Wall wherever possible. This allowed three main gates, each with two entrances, making the equivalent of six milecastle gates, to provide access to the north; the double-portal south gate was supplemented by two small side gates. The position of the forts and the provision of so many gates suggest that a requirement for increased mobility led to this change.

The addition of the forts was followed by the construction of an earthwork to the south 120 Roman feet (an actus – about 35 metres) wide. This consisted of a central ditch between two mounds. Causeways, surmounted by gates, were provided at forts. The purpose of the Vallum, as this earthwork is known, was presumably to protect the rear of the frontier zone.

After the forts had been added, the width of the Wall was narrowed to 8 Roman feet (2.4 metres) or less and the standard of craftsmanship reduced, both presumably in order to speed work.

Route

Sections of Hadrian’s Wall still remain, particularly in its hilly central sector. Little remains in lowland regions, where the Wall was plundered as a source of free stone for new buildings.

Hadrian’s Wall extended west from Segedunum at Wallsend on the River Tyne, via Carlisle and Kirkandrews-on-Eden, to the shore of the Solway Firth, ending a short but unknown distance west of the village of Bowness-on-Solway. The A69 and B6318 roads follow the course of the wall from Newcastle upon Tyne to Carlisle, then along the northern coast of Cumbria (south shore of the Solway Firth). The route was slightly north of Stanegate, an important Roman road built several decades earlier to link two forts that guarded important river crossings: Corstopitum (Corbridge) on the River Tyne and Luguvalium (Carlisle) on the River Eden.

Although the curtain wall ends near Bowness-on-Solway, this does not mark the end of the line of defensive structures. The system of milecastles and turrets is known to have continued along the Cumbria coast as far as Risehow, south of Maryport. For classification purposes, the milecastles west of Bowness-on-Solway are referred to as Milefortlets.

Historical background

In 79 AD Agricola subdued the Brigantes of northern England and the Selgovae along the southern coast of Scotland, using overwhelming military power to establish Roman control. He built a network of military roads and forts to secure the Roman occupation from around 80 AD.

After Agricola was recalled from Britain in 84 AD the Romans retired to a more defensible line along the Forth–Clyde isthmus, and with the decline of imperial ambitions in Scotland (and Ireland) by AD 87 (the withdrawal of the XX legion), consolidation based on the line of the Stanegate road (between Carlisle and Corbridge) was settled upon. Carlisle was the seat of a ‘centurio regionarius’ (or ‘district commissioner’). When the Stanegate became the new frontier it was augmented by large forts as at Vindolanda and additional forts at half-day marching intervals were built at Newbrough, Magnis (Carvoran) and Brampton Old Church.

While only a few sites north of the Stanegate line were maintained, there does not seem to have been any rout as a result of battles with various tribes.

Modifications to the Stanegate line, with the reduction in the size of the forts and the addition of fortlets and watchtowers between them, seem to have taken place from the mid-90s onwards. Apart from the Stanegate line, other forts existed along the Solway Coast at Beckfoot, Maryport, Burrow Walls (near to the present town of Workington) and Moresby (near to Whitehaven). Other forts in the region were built to consolidate Roman presence (Beckfoot, for example may date from the late 1st century). A fort at Troutbeck may have been established from the period of Trajan (emperor 98–117) onwards. Other forts that may have been established during this period include Ambleside (Galava), positioned to take advantage of ship-borne supply to the forts of the Lake District. From here, a road was constructed during the Trajanic period to Hardknott Roman Fort. A road between Ambleside to Old Penrith and/or Brougham, going over High Street, may also date from this period.

Purpose of Wall construction (wiki)

On Hadrian’s accession to the imperial throne in 117, there was unrest and rebellion in Roman Britain and from the peoples of various conquered lands across the Empire, including Egypt, Judea, Libya and Mauretania. These troubles may have influenced his plan to construct the Wall, as well as his construction of frontier boundaries now known as limes in other areas of the Empire, such as the Limes Germanicus in modern-day Germany. In any case, Hadrian ended his predecessor Trajan’s policy of expanding the empire and instead focused on defending the current borders.

The Historia Augusta states that Hadrian was the first to build a wall 80 miles from sea to sea to separate the barbarians from the Romans. However, this reasoning may not entirely explain all the various motivations Hadrian could have had in mind when commissioning the wall’s construction.

Scholars disagree over how much of a threat the inhabitants of northern Britain really presented to the Romans, and whether there was any economic advantage in defending and garrisoning a fixed line of defences like the Wall, rather than conquering and annexing what has become Northumberland and the Scottish Lowlands and then defending the territory with a looser arrangement of forts.

According to restored sandstone fragments found in Jarrow which date from 118 or 119, it was Hadrian’s wish to keep “intact the empire”, which had been imposed on him via “divine instruction”. Besides a defensive structure made to keep people out, the Wall also served to keep people within the Roman province. Since the Romans had control over who was allowed in and out of the empire, the Wall was invaluable in controlling trading and the economy.

Recent thought is that the Wall’s primary purpose was as a physical barrier to slow up the crossing of raiders and people intent on getting into the empire for destructive or plundering purposes. It may be that the Wall was not a last-stand type of defensive line, but instead an observation point that could alert Romans of an incoming attack and act as a deterrent to slow down enemy forces so that additional troops could arrive for support.This view is supported by another defensive measure frequently found on the berm or flat area in front of the Wall: pits or holes known as cippi pits which held branches or small tree trunks entangled with sharpened branches (these were the ‘cippi’). The use of such thorns and sharpened stakes was clearly an anti-personnel measure, and might be thought of as the Roman equivalent of barbed wire.

It took six years to build most of Hadrian’s Wall at the hands of three Roman legions – the Legio II Augusta, Legio VI Victrix, and Legio XX Valeria Victrix, totalling 15,000 soldiers, plus some members of the Roman fleet. The production of the Wall was not out of the area of expertise for the soldiers, as some would have trained to be surveyors, engineers, masons, and carpenters.

Once its construction was finished, there is some evidence that Hadrian’s Wall was covered in plaster and then whitewashed: its shining surface would have reflected the sunlight and been visible for miles around.

“Broad Wall” and “Narrow Wall”

R.G. Collingwood cited evidence for the existence of a broad section of the Wall and conversely a narrow section. He argued that plans changed during construction of the Wall and its overall width was reduced.

Broad sections of the Wall are around nine and a half feet (2.9 metres) wide with the narrow sections of the Wall two feet (60 centimetres) thinner, being around seven and a half feet (2.3 metres) wide. The narrow sections were found to be built upon broad foundations. Based on this evidence, Collingwood concluded that the Wall was originally due to be built between present-day Newcastle and Bowness, with a uniform width of ten Roman feet, all in stone. However, in the end, only three-fifths of the Wall was built from stone and the remaining part of the Wall in the west was a turf wall, though it was later rebuilt in stone. Plans possibly changed due to a lack of resources.

In an effort to preserve resources further, the eastern half’s width was therefore reduced from the original ten Roman feet to eight, with the remaining stones from the eastern half used for around five miles (8 kilometres) of the turf wall in the west. This reduction from the original ten Roman feet to eight, created the so-called “Narrow Wall”.

The Vallum

Just south of the Wall there is a ten-foot (3 metres) deep, ditch-like construction with two parallel mounds running north and south of it, known as the Vallum. The Vallum and the Wall run more or less in parallel for almost the entire length of the wall, except between the forts of Newcastle and Wallsend at the east end of the Wall, where the Vallum may have been considered superfluous on account of the close proximity of the River Tyne, at the north bank of which the Wall ended (or began).

From 1936, research showed that the Vallum was built shortly after the Wall because the Vallum clearly avoided one of the Wall’s milecastles. This new discovery was continually supported by more evidence, strengthening the idea that there was a simultaneous construction of the Vallum and the Wall.

Other evidence still pointed in other, slightly different directions. Evidence shows that the Vallum preceded sections of the Narrow Wall specifically; to account for this discrepancy, Couse suggests that either construction of the Vallum began with the Broad Wall, or it began when the Narrow Wall succeeded the Broad Wall but proceeded more quickly than that of the Narrow Wall.

The vallum was crossed by causeways only at the forts and strangely seems to have been designed as a barrier to the south. Traffic would have to cross these causeways and then travel along the military road to one of the milecastles to cross the Wall, as farm animals would not have been allowed through the forts. However, modern archaeological opinion is that the Vallum established the southern boundary of an exclusion zone bounded on the north by the wall itself and would have been “out-of-bounds” to civilians. It might thus have been the Roman equivalent to a modern demilitarized zone. 😊

The Vallum limited the routes through the Wall from 78 to about 15 and may therefore have been constructed in response to a threat from the south.

Turf wall

From Milecastle 49 to the western terminus of the wall at Bowness-on-Solway, the curtain wall was originally constructed from turf, possibly due to the absence of limestone for the manufacture of mortar. Subsequently, the Turf Wall was demolished and replaced with a stone wall. This took place in two phases; the first (from the River Irthing to a point west of Milecastle 54), during the reign of Hadrian, and the second following the reoccupation of Hadrian’s Wall subsequent to the abandonment of the Antonine Wall (though it has also been suggested that this second phase took place during the reign of Septimius Severus). The line of the new stone wall follows the line of the turf wall, apart from the stretch between Milecastle 49 and Milecastle 51, where the line of the stone wall is slightly further to the north.

In the stretch around Milecastle 50TW, it was built on a flat base with three to four courses of turf blocks. A basal layer of cobbles was used westwards from Milecastle 72 (at Burgh-by-Sands) and possibly at Milecastle 53. Where the underlying ground was boggy, wooden piles were used.

At its base, the now-demolished turf wall was 6 metres (20 feet) wide, and built in courses of turf blocks measuring 46 cm (18 inches) long by 30 cm (12 inches) deep by 15 cm (6 inches) high, to a height estimated at around 3.66 metres (12.0 feet). The north face is thought to have had a slope of 75%, whereas the south face is thought to have started vertical above the foundation, quickly becoming much shallower.

Conclusion

Speculation on the reason periods of construction and design are open to active debate as the current archaeological evidence is sparse and more of a judgement call rather than scientific evidenced based hypothesises.

What we will do in this essay is to look at real evidence in the form of LiDAR maps and ascertain what came first and what was already in place and the reasons they used these landscape structures.

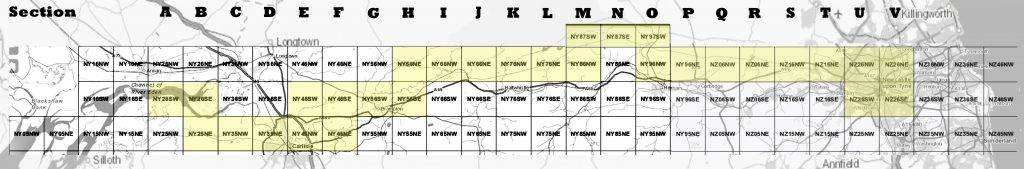

Do this with any relevant accuracy we need to establish a grid system that look at all the LiDAR, satellite photography, Old OS maps and excavation evidence to draw new conclusions to the construction of Hadrian’s Wall.

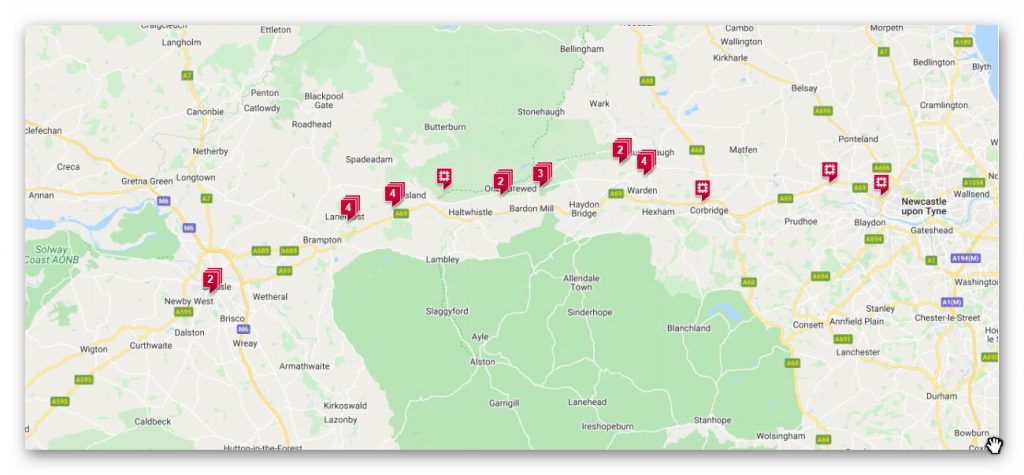

We have therefore subdivided Hadrian’s wall into 23 sections A to W, and we will subsequently investigate each section – CLICK on the section listing to see the Lidar and GE details and investigation conclusions.

Section A – NY26SW

Section B – NY26SE & NY25NE

Section C – NY35NW

Section D – NY35NE

Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

Section G – NY56SW

Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

Section I – NY66NW

Section J – NY66NE

Section K – NY76NW

Section L – NY76NE

Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

Section N – NY87SE

Section O – NY97SW – NY96NW

Section P – NY96NE

Section Q – NZ06NW

Section R – NZ06NE

Section S – NZ16NW

Section T – NZ16NE

Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

To understand the problem with Hadrian’s Walls history read our article HERE.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.