Section G – NY56SW

Contents

Section D – NY35NE – this is a section of Hadrian’s Wall showing the LiDAR, Google Earth and 1800 Maps of the Area covered by Historic England

Historic England Sections:

Hadrian’s Wall – west of Coombe Crag and Oldwall in wall miles 54, 55, 56 and 57

List UID: 1010986, 1010987, 1010985, 1010983, 1010982

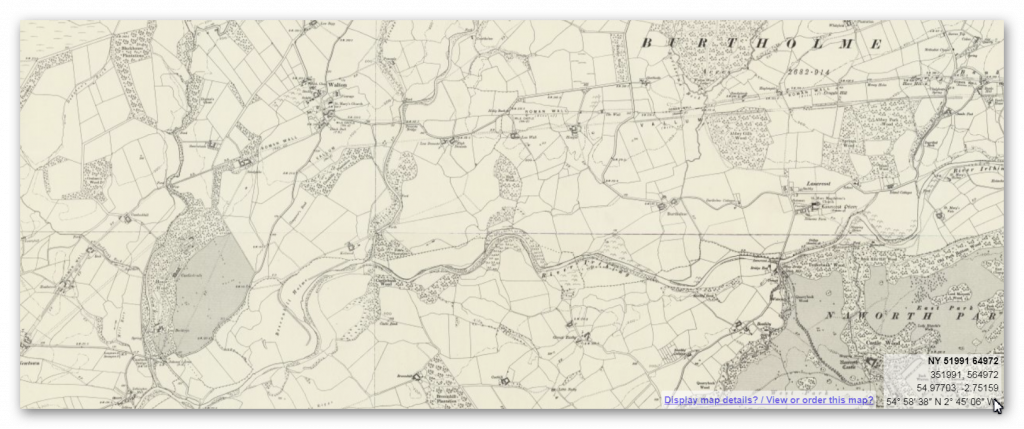

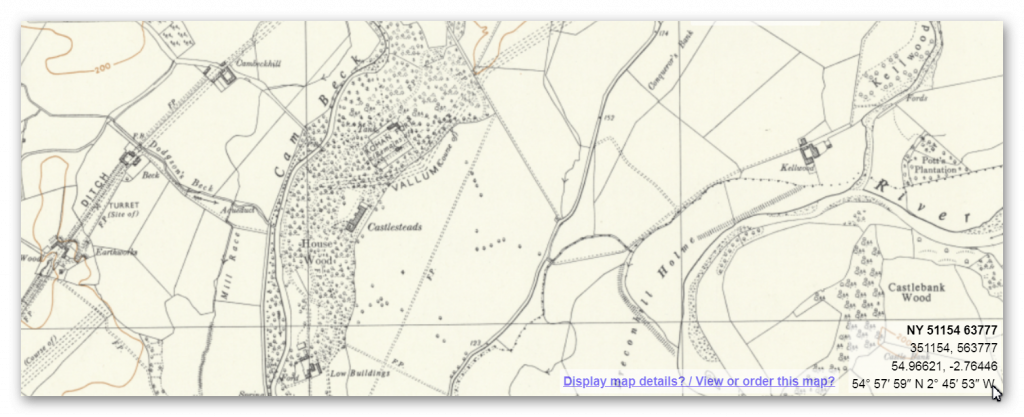

Old OS Map

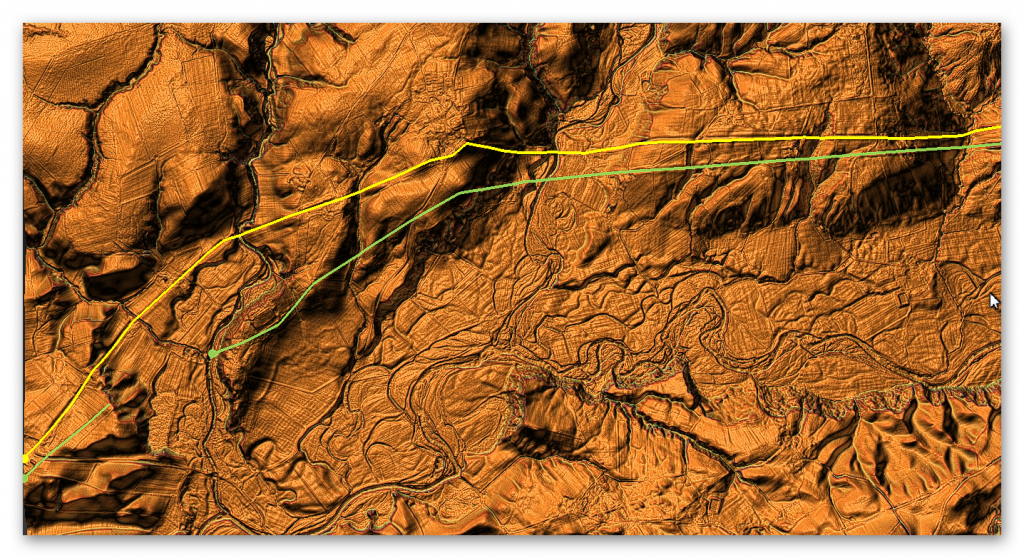

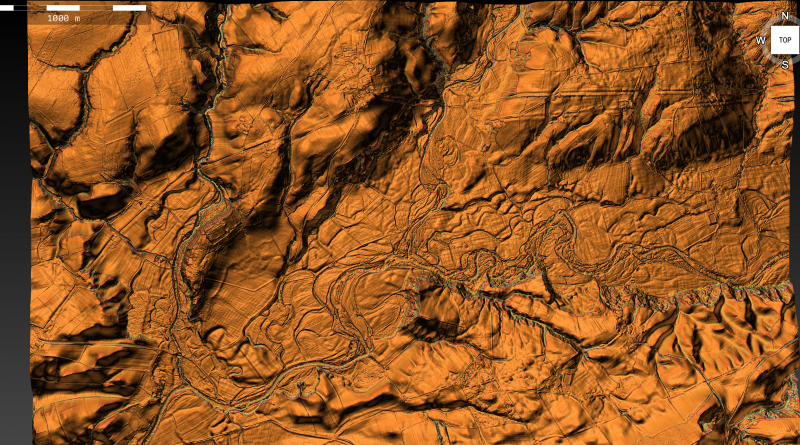

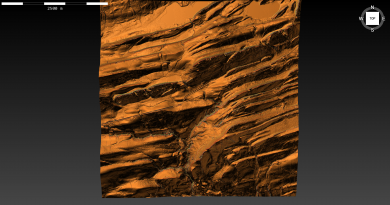

LiDAR Map

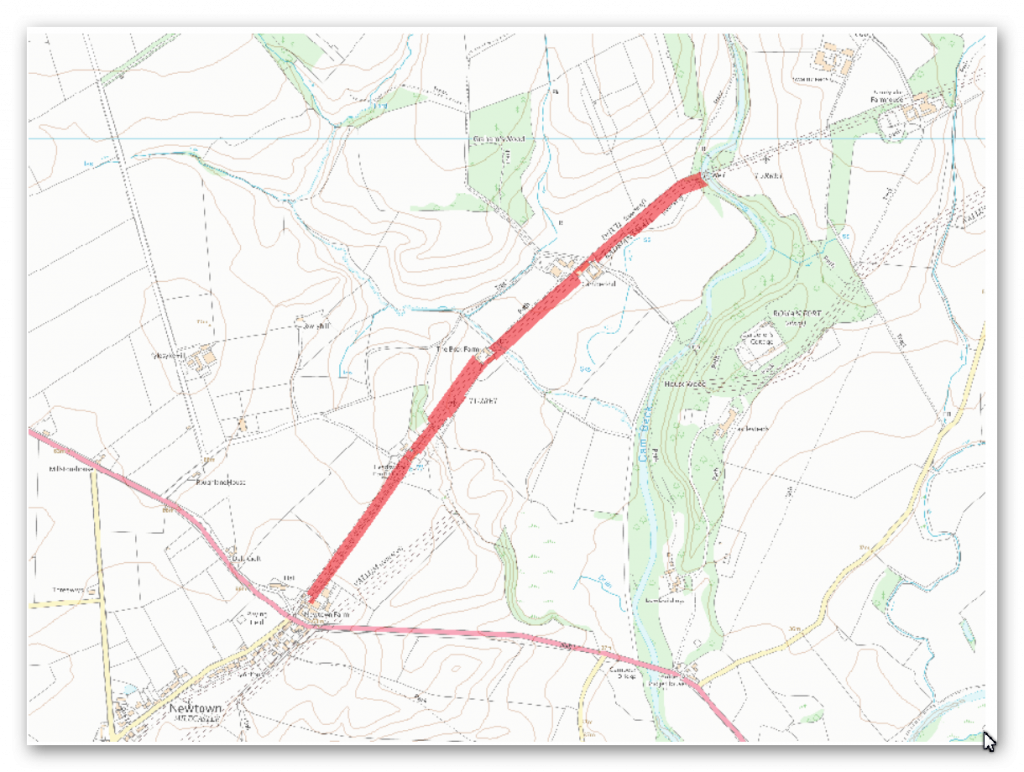

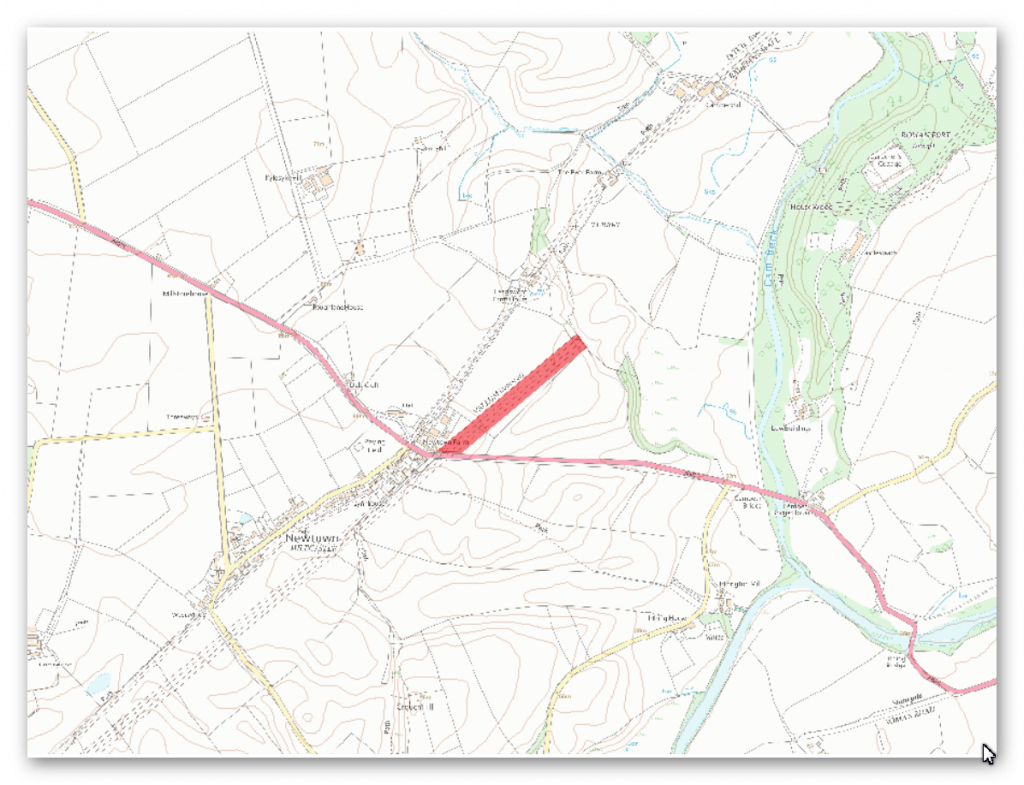

Google Earth Map

Historic England Scheduled Monuments within Section G

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between the Cam Beck and Newtown Farm in wall miles 56 and 57

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010986

Name: The vallum between the field boundary south east of Heads Wood and the A6071 road in wall mile 57

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010987

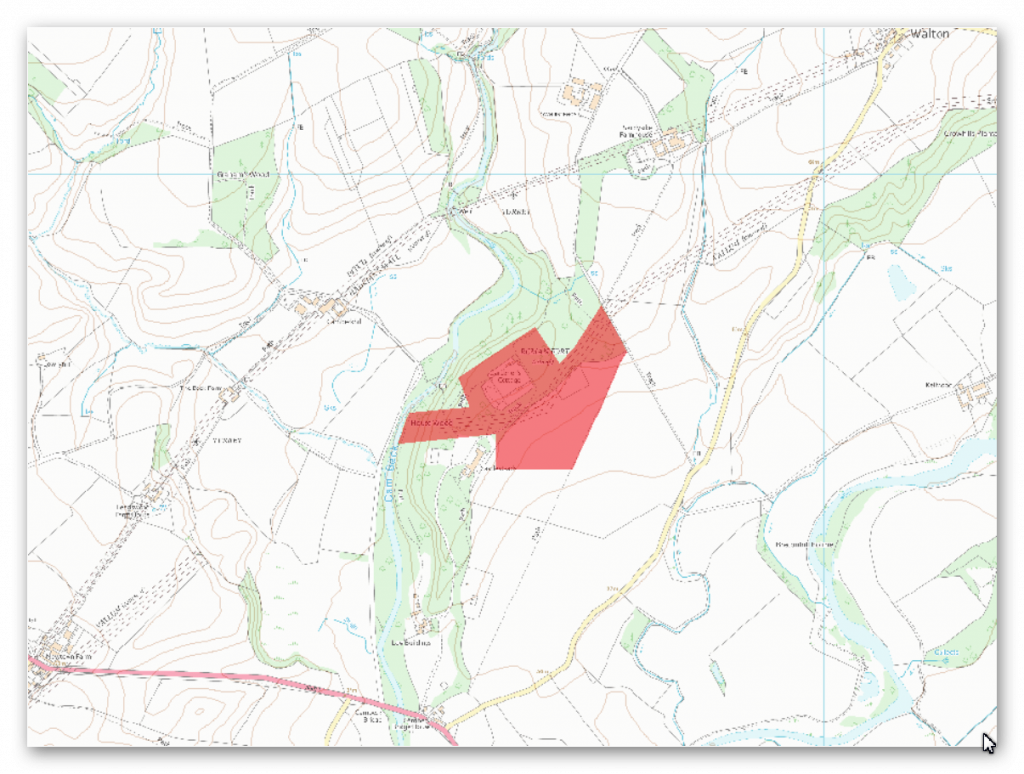

Name: Castlesteads Roman fort and the vallum between the track to the east of Castlesteads fort and the Cam Beck in the west

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010985

Name: The vallum between the road to Garthside and the track east of Castlesteads in wall miles 54, 55 and 56

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010983

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between the road to Garthside and The Centurion Inn, Walton, in wall miles 54 and 55

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010982

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and its associated features between the Cam Beck in the east and Newtown Farm in the west. Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout this section with no remains visible above ground. Its course is indicated in this section by a broad swelling in the field to the south west of Cambeckhill farm and as occasional rises in hedgelines which cross its course.

There is no surface trace at The Beck Farm or Heads Wood house. The wall ditch survives as an intermittent earthwork visible on the ground. Where extant it averages 2m deep in the east half of the section and 1m deep in the west half. The ditch upcast mound, usually referred to as the glacis, has been ploughed out in this section and only survives faintly visible in the field south west of The Beck Farm.

The exact location of milecastle 57 has not yet been confirmed as there are no upstanding remains surviving above ground. However, on the basis of the usual spacing it is expected to be located below the farm at Cambeckhill. These buildings and the ground below them are not included in the scheduling as the survival of archaeological remains there has not been confirmed. Turret 57a is situated about 180m south west of Dodgson’s Beck. It was located in 1933 by Simpson who confirmed it as one from the Turf Wall series. It survives as a buried feature with a slight swelling visible above ground, 0.15m high, in the turf cover. The exact location of turret 57b has not yet been confirmed. However, on the basis of the usual spacing it is expected to be situated about 110m north east of Newtown Farm.

The exact course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has not been confirmed in this section. It is probably positioned parallel to the Wall about 20m-30m south of it throughout the section as there are no topographical constraints.

The monument includes the section of vallum between the field boundary to the south east of Heads Wood in the east and the A6071 road in the west. The vallum survives as a buried feature throughout this short section with no upstanding remains visible above ground. However, vague traces of the silted ditch are marked by slight depressions in the hedgelines which cross its course.

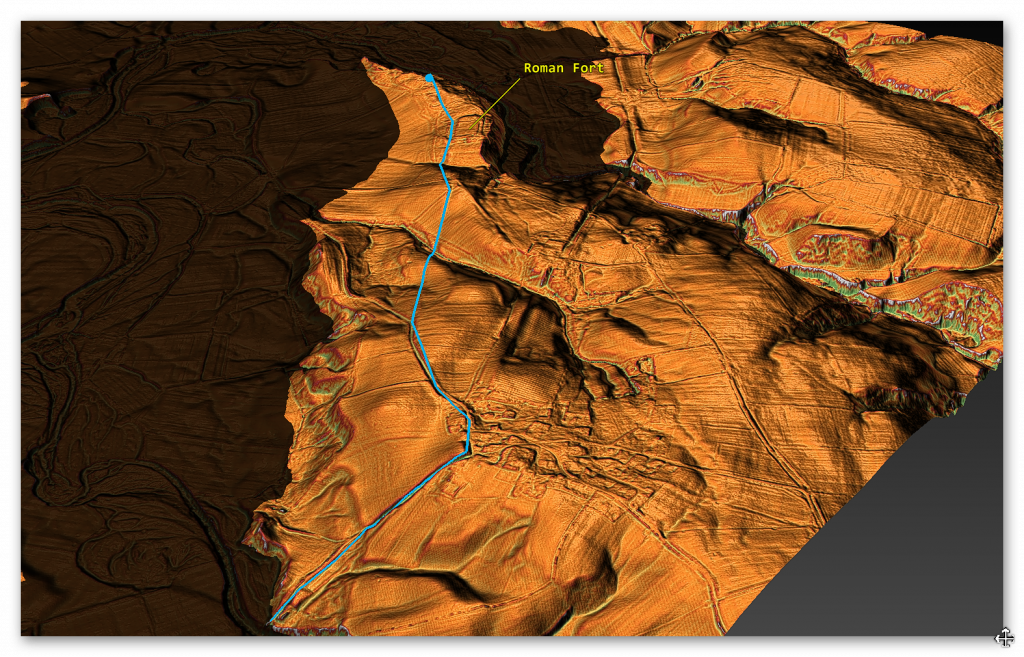

The monument includes the Roman fort and its associated remains at Castlesteads and the section of vallum between the track to the east of Castlesteads and the Cam Beck in the west. Castlesteads fort, known to the Romans as `Camboglanna’, is detached from the Wall line, being located 350m to the south of the Wall. This is accounted for by the strength of the position the fort occupies and also the need for the Wall line to take a more gentle descent of the gorge to cross the Cam Beck. The fort is situated on a high bluff and was built here to command the Cam Beck valley.

The fort survives as a low platform with most of its remains surviving as buried features. The surface remains of the fort were damaged by landscaping for Castlesteads house in 1791. The fort is now overlain by ornamental gardens. The stone fort measures about 114m square internally and encloses an area of at least 1.3ha. The north west side of the fort has been eroded by the Cam Beck so that the east and west gateways was now lie just 15m from the lip of the gorge. Limited excavations were carried out by Richmond and Hodgson in 1934 who were able to locate the ramparts and east and west gateways and establish the existence of a berm, 3m wide, and an outer ditch 4.8m wide. Trenching at the south east angle revealed the remains of a turf rampart, at least 3m wide, resting on flagging and stones set in clay to the rear of the Stone Wall. This rampart base is probably the remains of an earlier turf and timber fort which occupied the site. An east facing scarp, 0.4m high, parallel to the east rampart was discovered during a survey by the Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of England in 1991.

This scarp may be the remains of the edge of the platform of this earlier and therefore larger fort, especially as a right-angled return to the south west can be traced for 10m before fading. A section of ditch thought to be associated with an annexe was also discovered during Richmond and Hodgson’s excavations. Inscriptions from the site show that the fort was garrisoned by the fourth cohort of Gauls in the second century AD and by the mounted second cohort of Tungrians in the third century AD. Large quantities of inscribed and sculptured stones have been found during the landscaping and stone robbing, many of which are housed in the summer house at the west side of the rose garden. These sculptured stones which are not included in the scheduling, include three altars dedicated to the Persian god Mithras and ten dedicated to the worship of official state gods. The bath house associated with the fort lies to the north east of the fort platform in dense woodland. It is the subject of a separate scheduling (SM 26081).

The remains of the civil settlement, or vicus, which is usually associated with Roman forts, are not visible as upstanding features at Castlesteads. However, a letter from a certain Richard Goodman writing to Gale in 1727 mentions traces of an extensive settlement on the slope at the south east front of the fort. He noted the existence of foundations of walls and streets which were being removed to construct new buildings and to allow the land to be ploughed. The remains of the vicus will survive as buried features below the ploughed field to the south and east of Castlesteads. However, a letter from a certain Richard Goodman writing to Gale in 1727 mentions traces of an extensive settlement on the slope at the south east front of the fort. He noted the existence of foundations of walls and streets which were being removed to construct new buildings and to allow the land to be ploughed. The remains of the vicus will survive as buried features below the ploughed field to the south and east of Castlesteads.

The vallum survives as a buried feature throughout this section with no remains visible above ground. Its course has been confirmed by Haverfield who cut trenches in 1898, 1901 and 1902 to determine its course. It was found to make a sweeping diversion to the south to encompass the fort at Castlesteads within the Wall-vallum zone. However, it makes the turn well before the stone fort implying that it was constructed to respect the earlier and larger turf and timber fort.

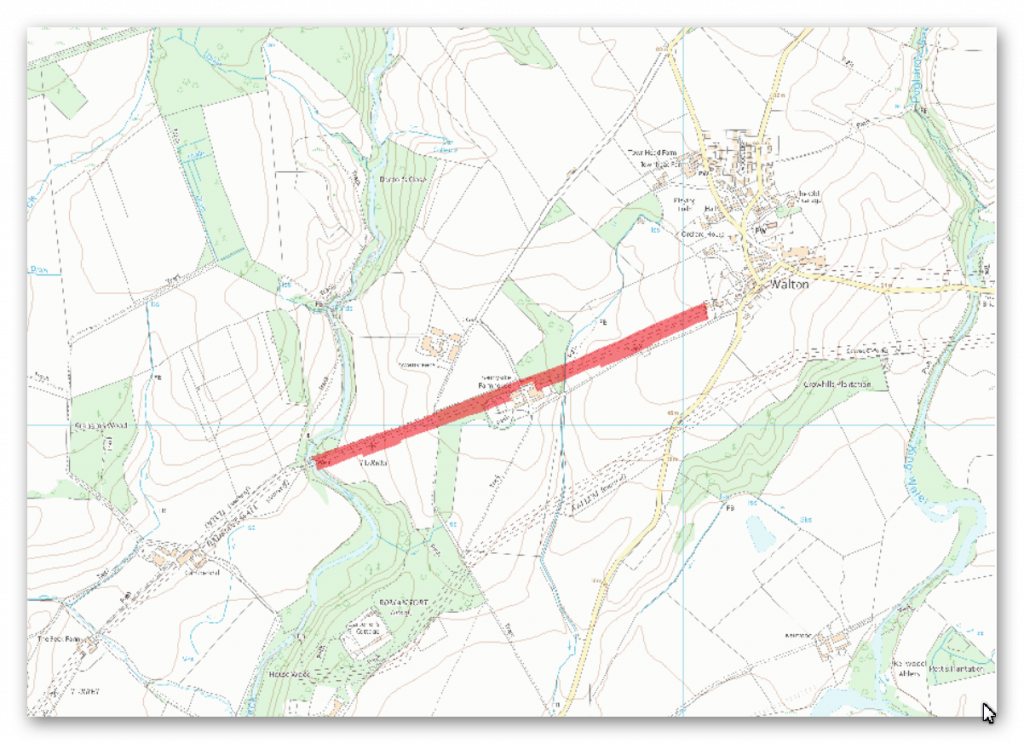

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and its associated features between Eden Vale house at Walton in the east and the Cam Beck in the west. Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature in the east half of this section with few traces visible above ground. In the woodland on the east and west sides of Sandysike the Wall is visible as an earth covered bank, 5.6m wide and 0.3m-0.5m high, with trees growing out of it.

Richmond noted deep masonry foundations of the Wall near the stream at Sandysike in 1933. Either side of the Cam Beck there are no upstanding remains of the Wall. However, its course is known because there is an account of the part destruction of the Wall here in 1791 where it is stated to have been 2.5m thick. The wall ditch survives as an intermittent earthwork visible on the ground throughout this section. East of Sandysike Wood the ditch is silted up leaving no surface traces. In the wood the ditch survives as a visible feature, averaging between 1.4m and 1.7m deep, with a drain occupying its base. West of the wood the ditch is partly overlain by a hedgeline before fading as it approaches the Cam Beck in boggy ground.

The ditch upcast mound, usually referred to as the glacis, which lies to the north of the ditch has been ploughed out throughout most of this section. The exact location of turret 56a has not been confirmed as there are no upstanding remains visible above ground. However, on the basis of the usual spacing it is expected to be located just to the east of Sandysike. Although not included in the scheduling, there is a Roman altar built into an outbuilding of Sandysike farm, 0.7m above ground level. It is made from red sandstone and measures 0.34m by 0.14m. Turret 56b is situated about 140m east of the Cam Beck on a river terrace. It was located in 1933 by Simpson who ascribed it to the Turf Wall series. The turret survives as a buried feature with no remains visible above ground.

The exact course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has not been confirmed in this section. It is expected to be located parallel to the Wall, 20m-30m to the south of it. The track from Sandysike farm to Walton, which lies parallel to the Wall, may overlie the course of the Military Way.

The monument includes the section of vallum and its associated features between the road to Garthside in the east and the track to the east of Castlesteads in the west. The vallum survives as buried feature throughout most of this section. It is best preserved to the west of Low Wall where the ditch is visible as a slight depression which deepens as it descends to the stream. Otherwise the only surface traces are slight rises and dips in hedgelines where they cross the ploughed down mounds and ditch of the vallum. Elsewhere the vallum mounds have been reduced by ploughing leaving no trace above ground. Similarly the vallum ditch has been entirely silted up leaving no obvious remains on the surface.

Where there are no surface traces the course of the vallum is known from excavations by Haverfield during 1900-1901. His trenches revealed the course of the vallum west of Howgill farm and to the south of Walton. About 30m east of the track to the east of Castlesteads, Haverfield’s excavation in 1901 showed that there was a major realignment in the course of the vallum here. This sharp southward turn was made to encompass the Roman fort at Castlesteads within the military corridor between the Wall and vallum.

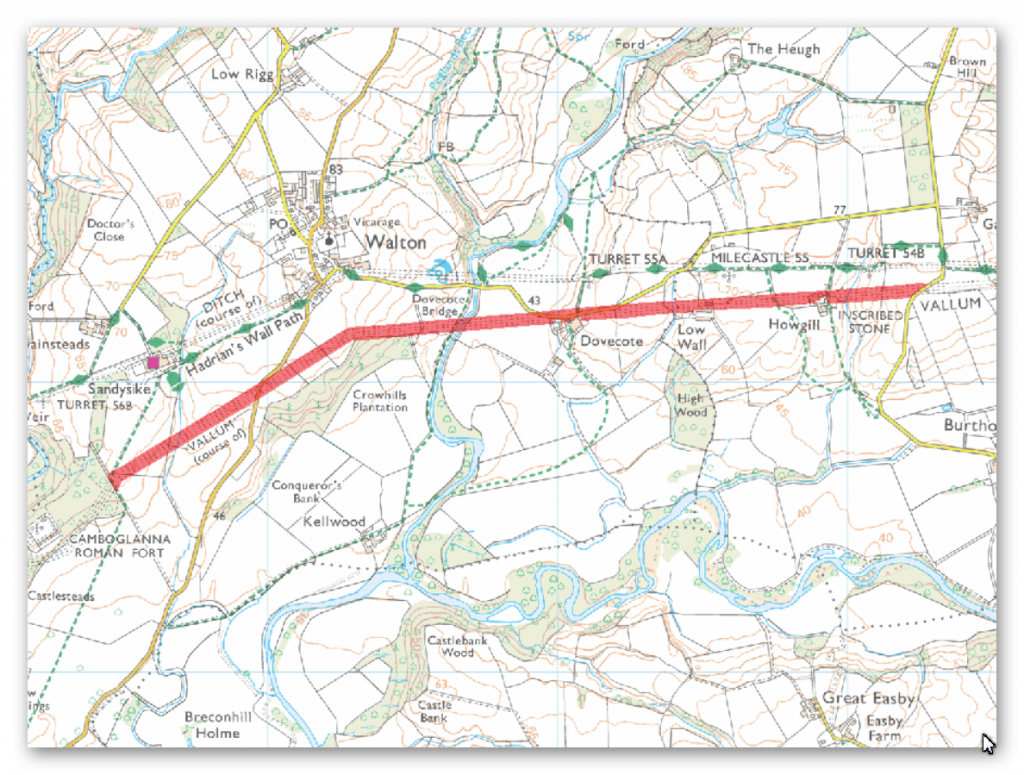

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and its associated features between the west side of the road to Garthside in the east and the Centurion Inn at Walton in the west. Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout this section with few traces visible on the ground. Between Howgill and turret 55a the Wall survives as a substantial turf covered bank, up to 1.4m high, which is surmounted by a fence and hedge. West of Dovecote Bridge a section of Wall 20m long stands to an average height of 1m. It is now covered by a protective mound of earth, and it is in the care of the Secretary of State.

Between this section of Wall and Walton the Wall was trenched in 13 places by Haverfield in 1902. The Wall was found to be substantially robbed along its course. Its line here is visible on the ground as an intermittent slight rise in grassland. Elsewhere in this section the Wall survives as a buried feature with no remains visible above ground except for the occasional rise seen in a hedgeline. The wall ditch survives as a feature visible on the ground as a slight depression, averaging 0.5m deep, throughout most of this section. It is best preserved to the east of turret 55a where it is 2.4m deep. The ditch upcast mound, usually referred to as the glacis, which lies to the north of the ditch has been ploughed out in this section. The only visible remains of this feature are to the east of turret 55a where it survives as a slight mound. Milecastle 55 survives as a low turf covered platform visible as a slight rise in the hedgeline. It measures 22m east to west but its north-south length is indeterminate because its extent to the south is unclear.

The milecastle was located and partly excavated by Haverfield in 1900 who recovered late fourth century AD pottery. Milecastle 56 is located to the north east of the Centurion Inn at Walton. It survives as a buried feature with no traces visible above ground. MacLauchlan noted slight traces of the milecastle here in 1858 during his survey of the Wall. Turret 54b is situated about 150m north east of Howgill House. It survives as a buried feature with no remains visible above ground. It was located by Simpson in 1933 who considered it to be of the original Turf Wall series. Turret 55a is situated about 170m to the north of High Dovecote. It survives as a buried feature with no remains visible above ground. This turret was also located by Simpson in 1933 who considered it to be of the original Turf Wall series. Turret 55b is situated about 40m west of Dovecote Bridge. Its exact location has not yet been confirmed as it survives as a buried feature with no remains visible above ground. The turret was located by Miss Kate Hodgson in 1959 but it has not been located since.

The exact course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has not been confirmed in this section. However, it is expected to be situated parallel to the Wall about 20m-30m south of it.

Investigation

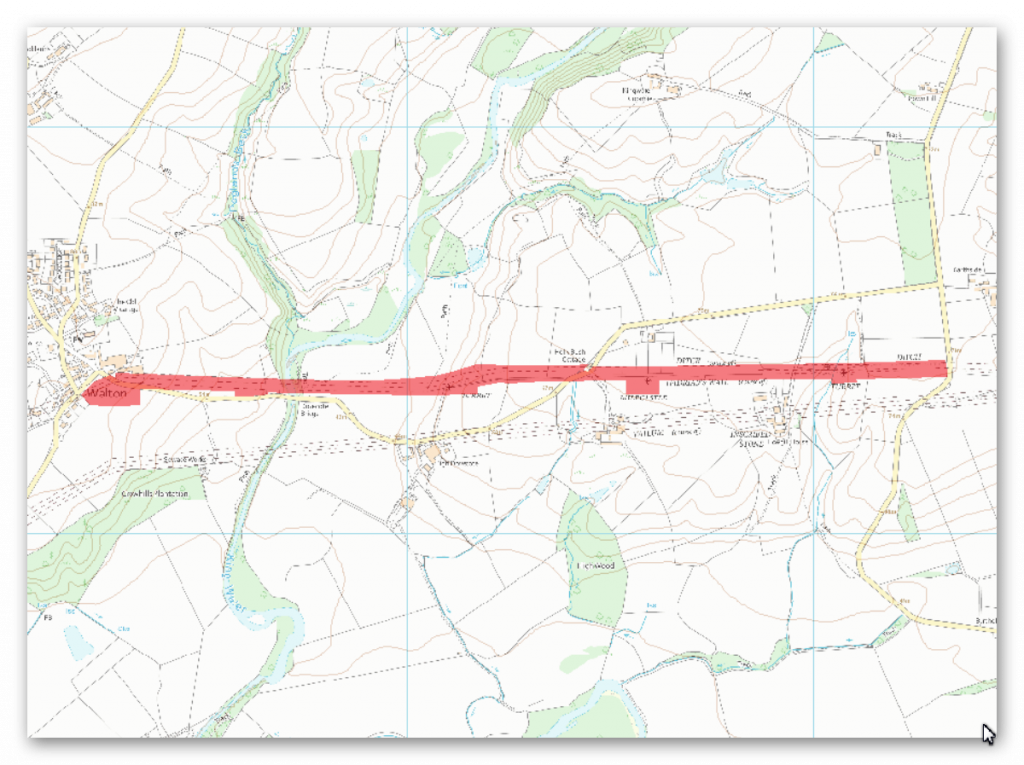

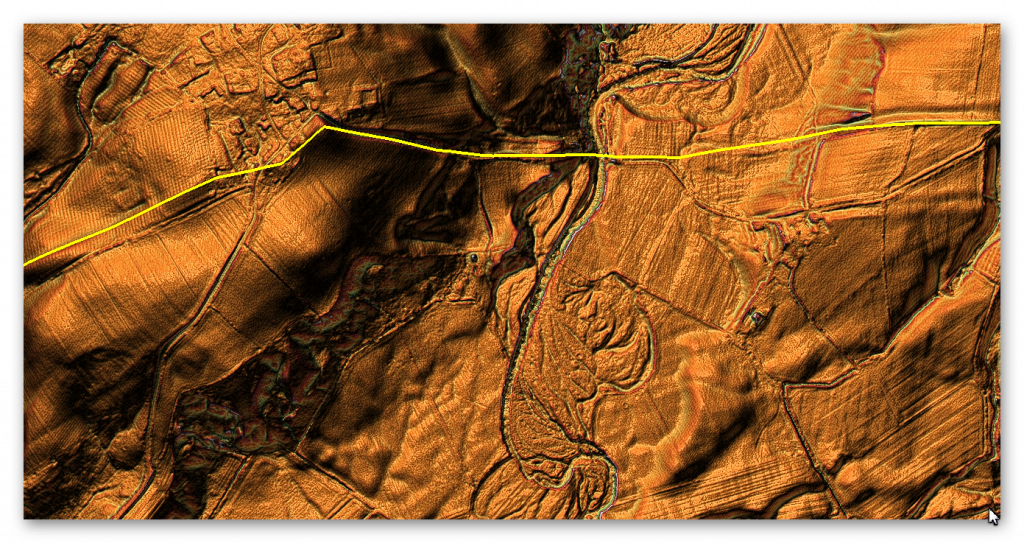

The Vallum in this section fades in and out depending on the location of the Valley floor – The OS maps give up in the west and attempts to discover the past in the East, although no evidence can be found in the central River Valley.

Another unexplained position is of a Roman Fort built to the South of the Wall for no reason, unless it was associated with the Vallum. The map seems to suggest that the Vallum came to the Fort (east side) rather than go around the base of the Camp in a strange bendy movement?

The Roman fort clearly predates the Wall as it would have no strategic significance as it is too far South. Therefore are we seeing the Early dates of the Building of the Vallum when the Romans used the existing prehistoric Dyke to Connect the Fort to the Englanged River and then adapted it to be part of the Vallum and The Wall ditch – although HE suggest that the Dyke is older than the Roman Building.

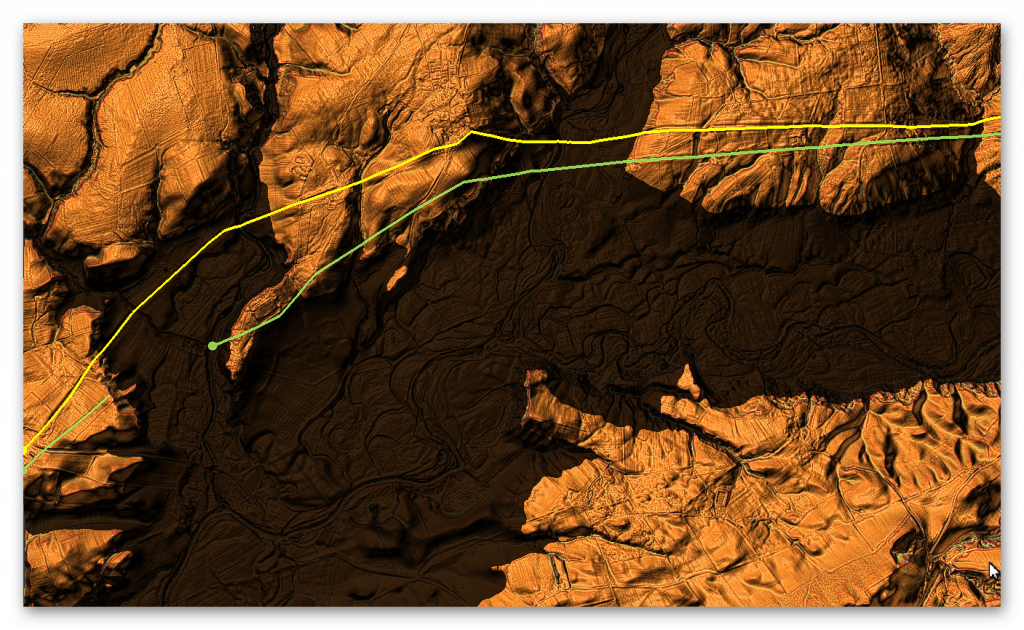

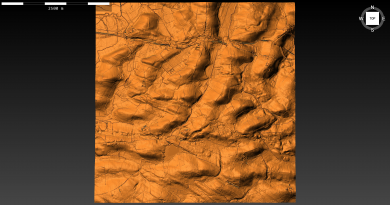

Vallum in Section G without water

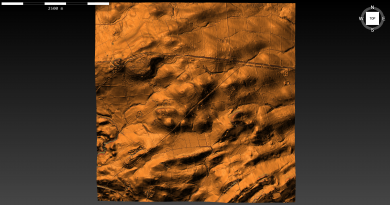

Vallum with Prehistoric Water

To understand the problem with Hadrian’s Walls history read our article HERE.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Pingback: Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation - Prehistoric Britain