Section J – NY66NE

Contents

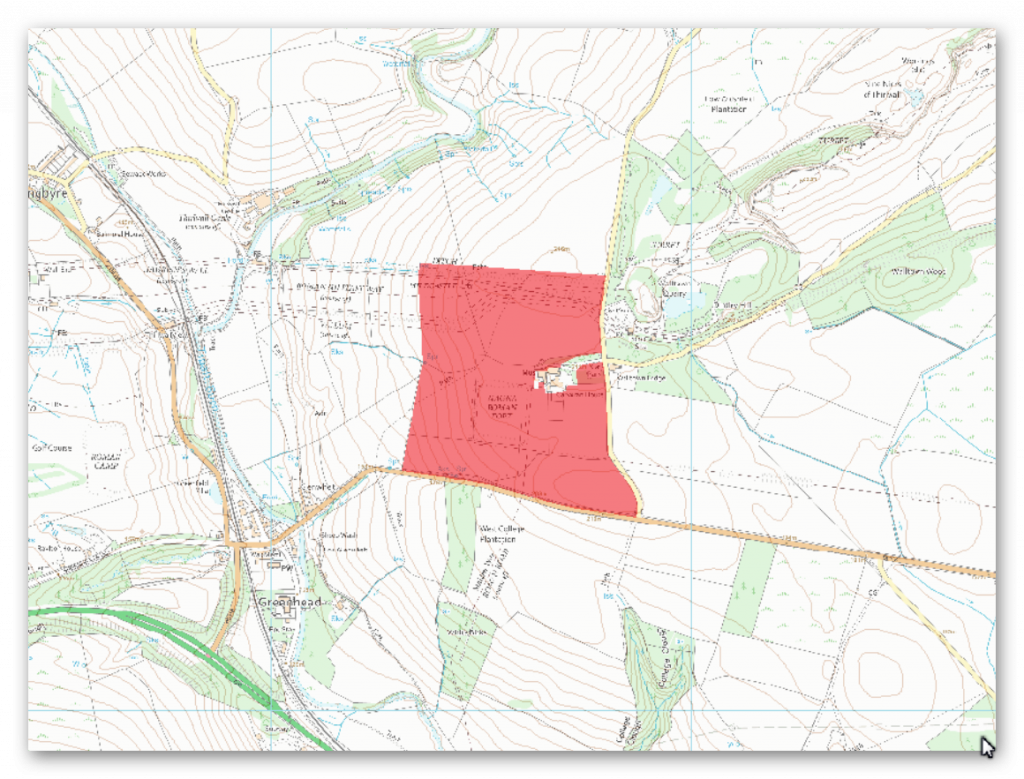

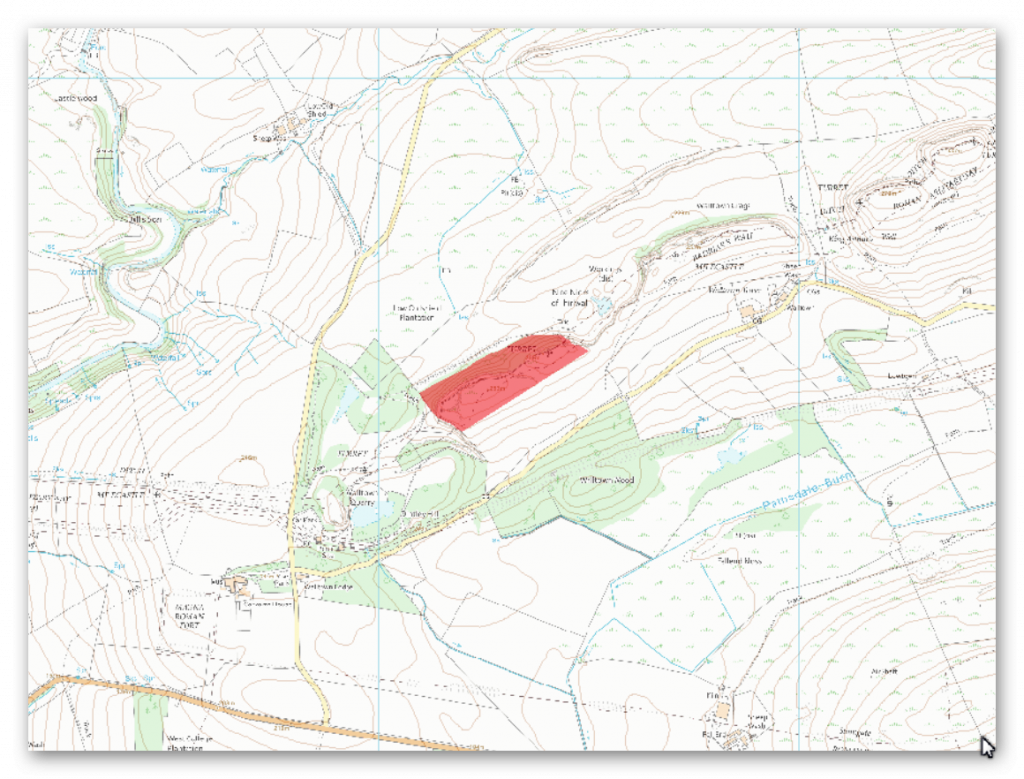

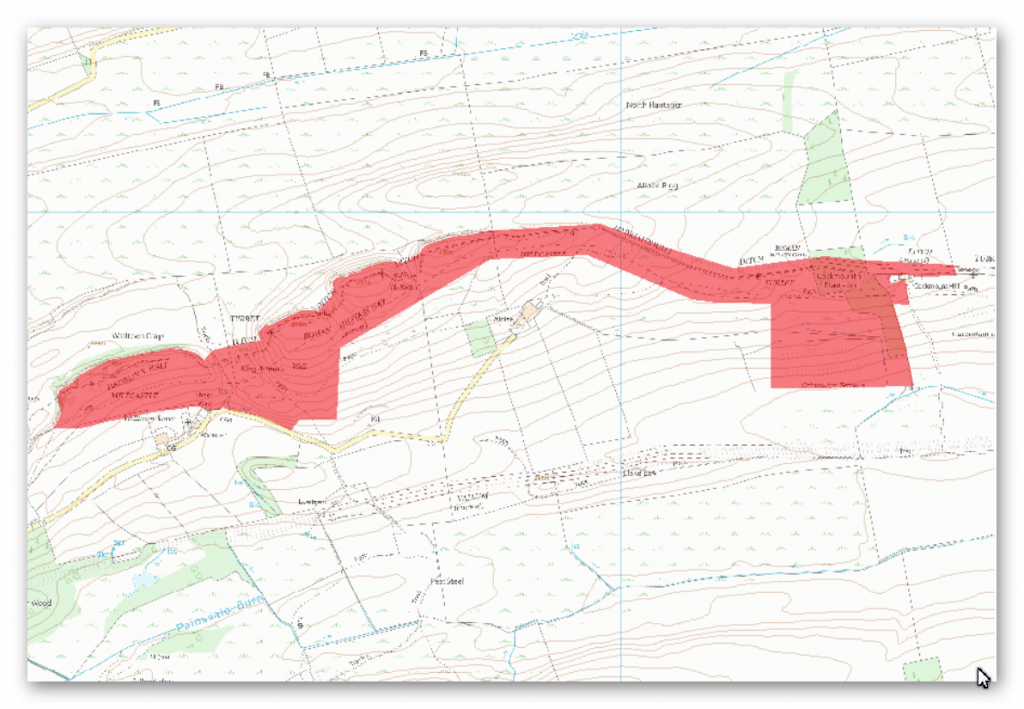

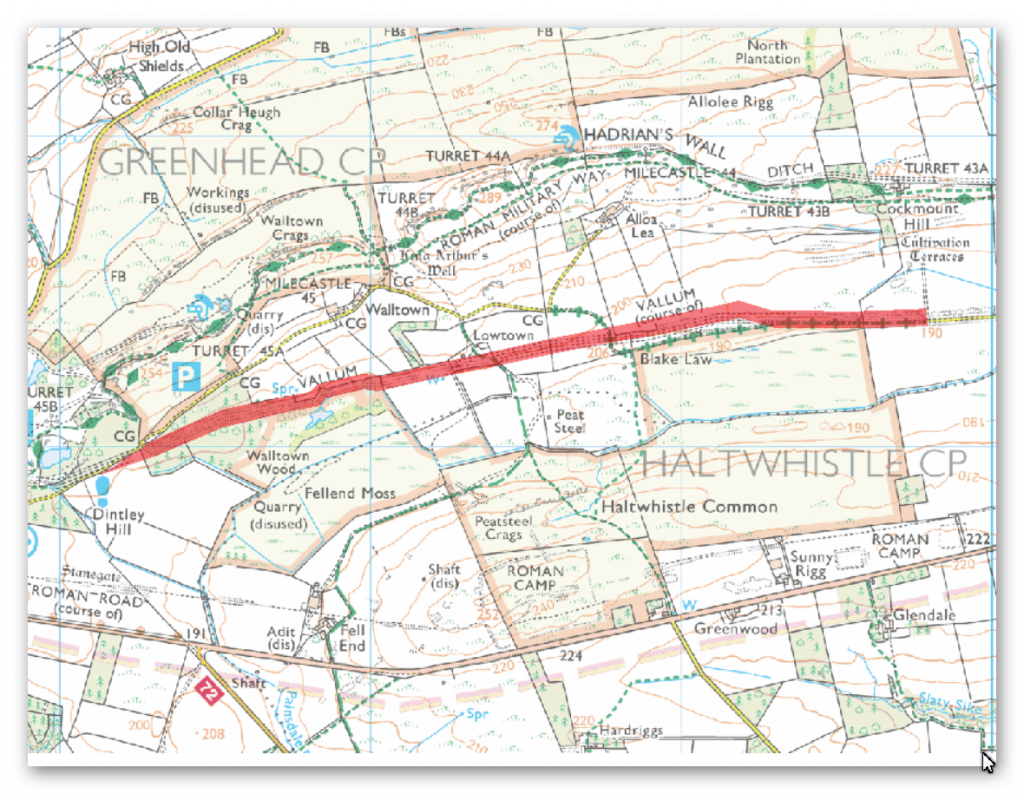

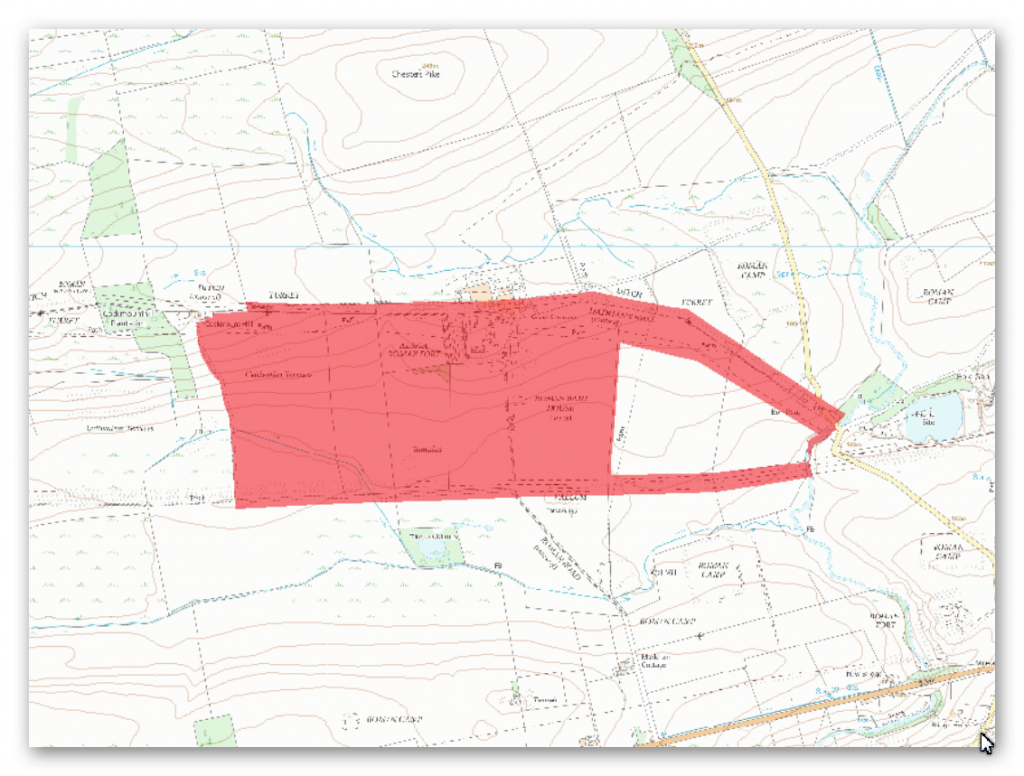

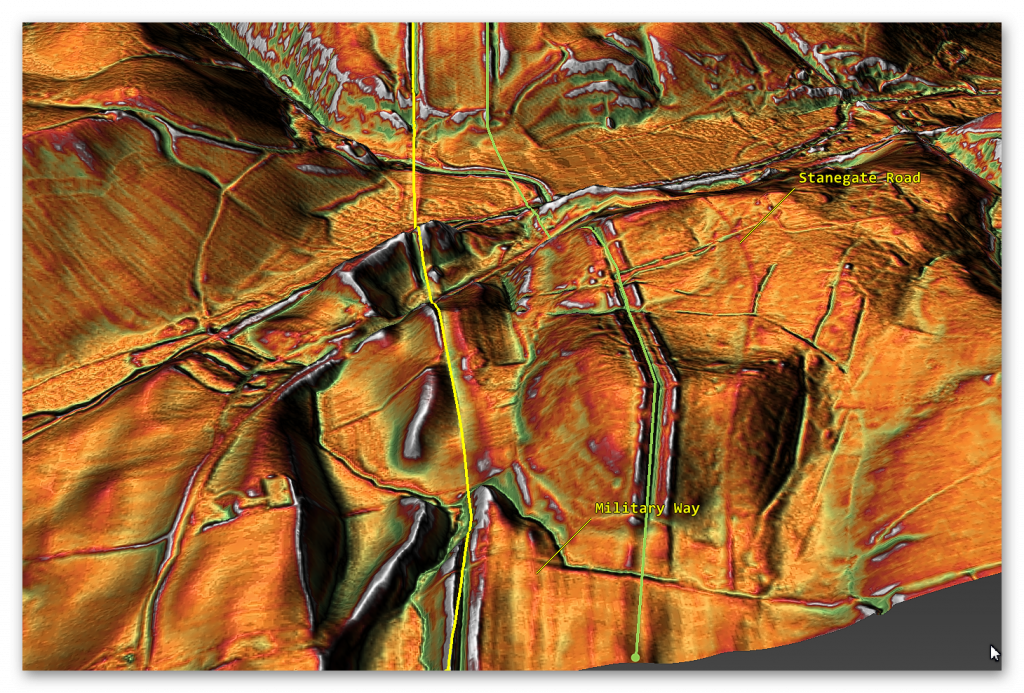

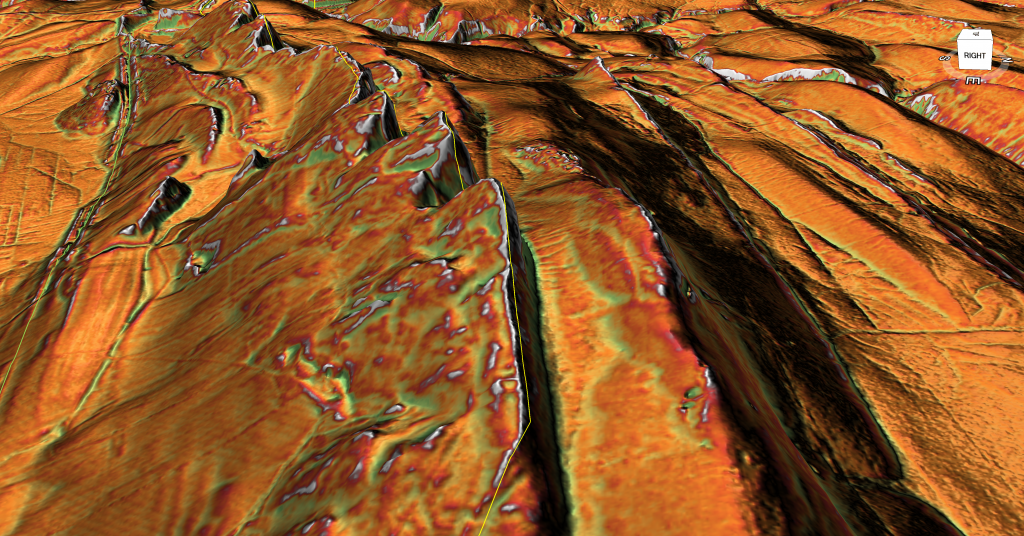

Section J – NY66NE – this is a section of Hadrian’s Wall showing the LiDAR, Google Earth and 1800 Maps of the Area covered by Historic England

Historic England Sections:

Name: Hadrian’s Wall, vallum, section of the Stanegate Roman road and a Roman temporary camp between the B6318 road and Cockmount Hill farm in wall miles 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 and 47

List UID: 1010993, 1010992, 1010991, 1010977,1017535, 1010978

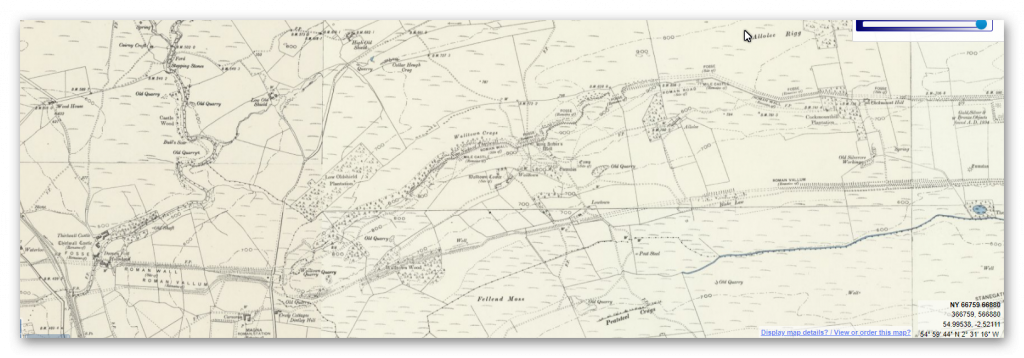

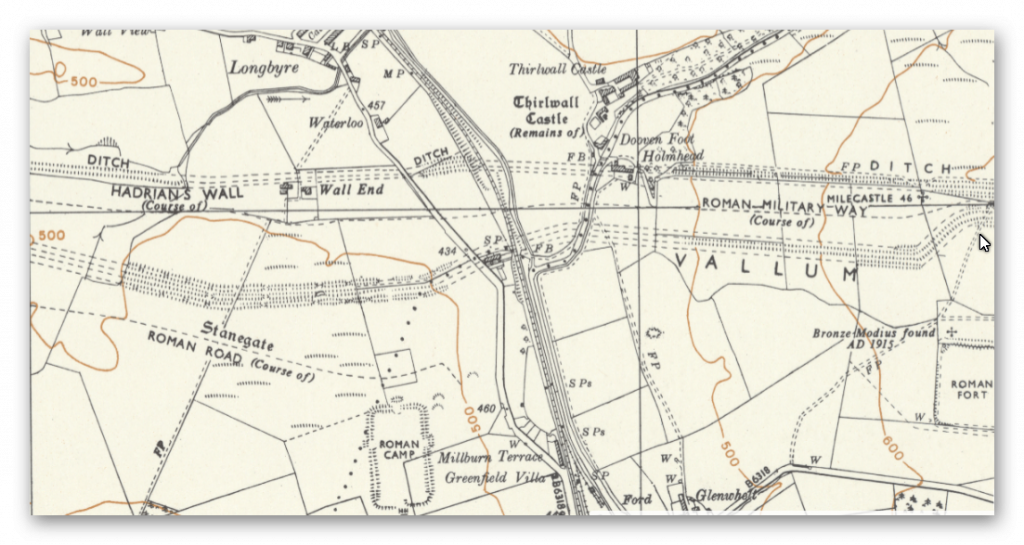

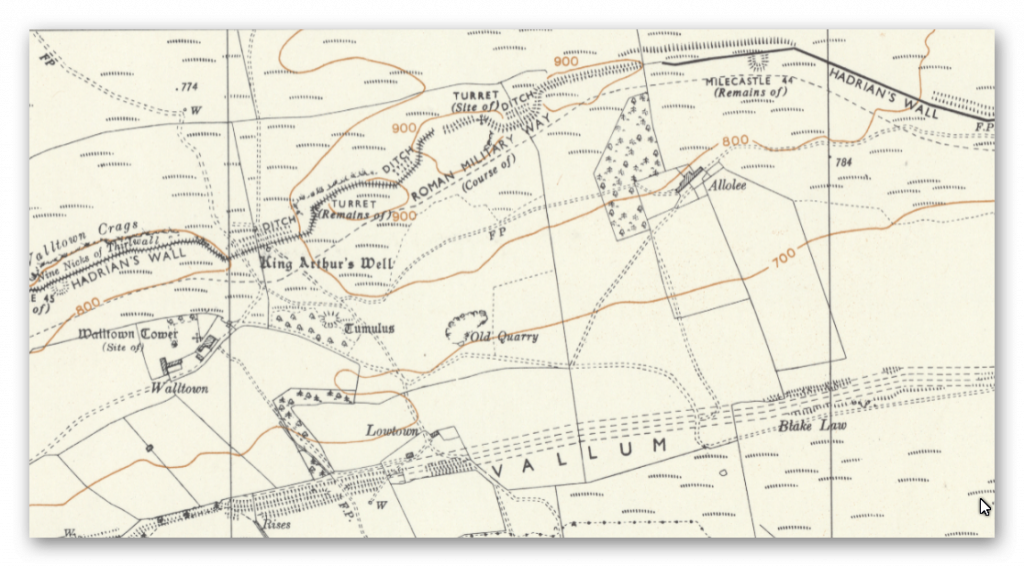

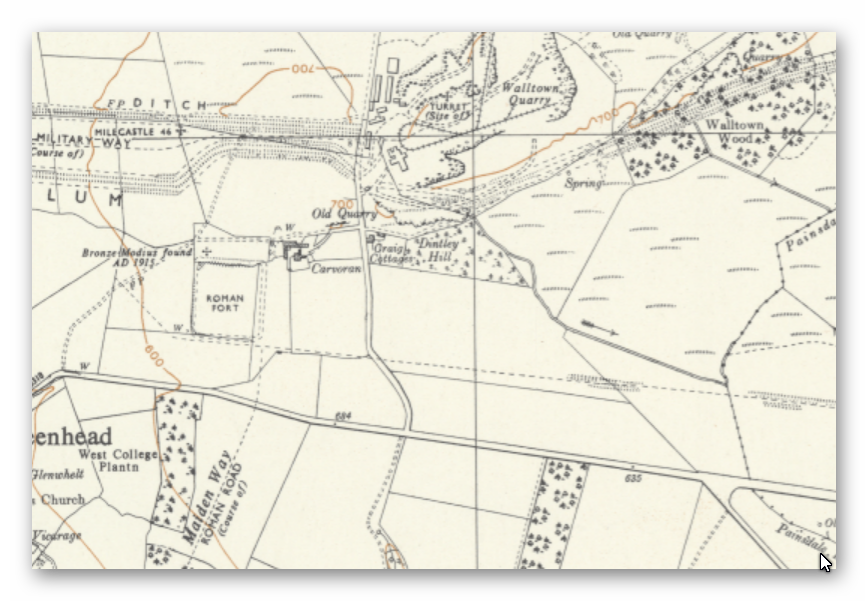

Old OS Map

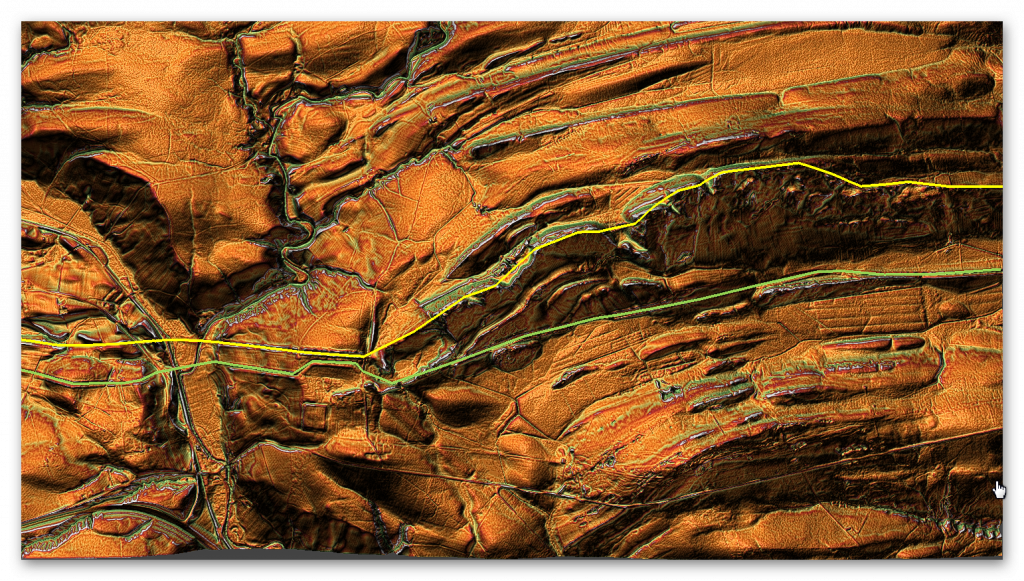

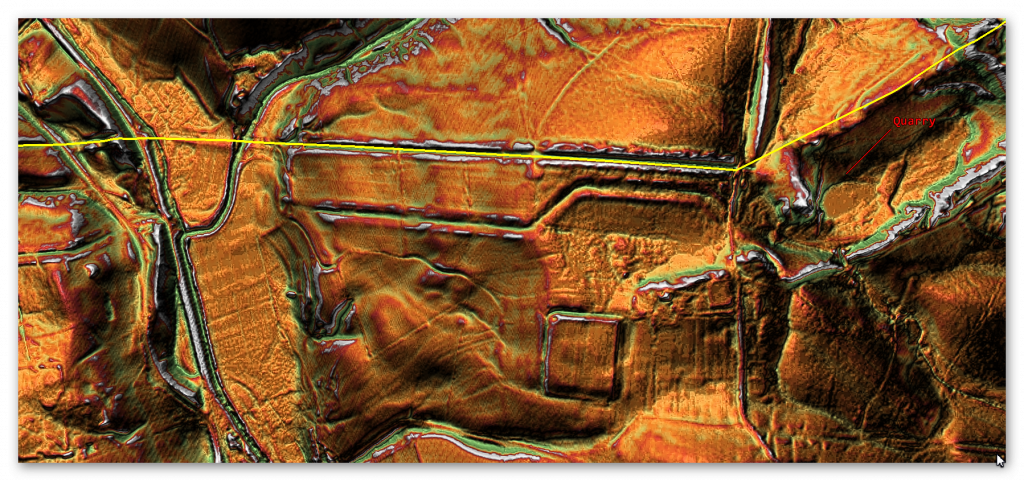

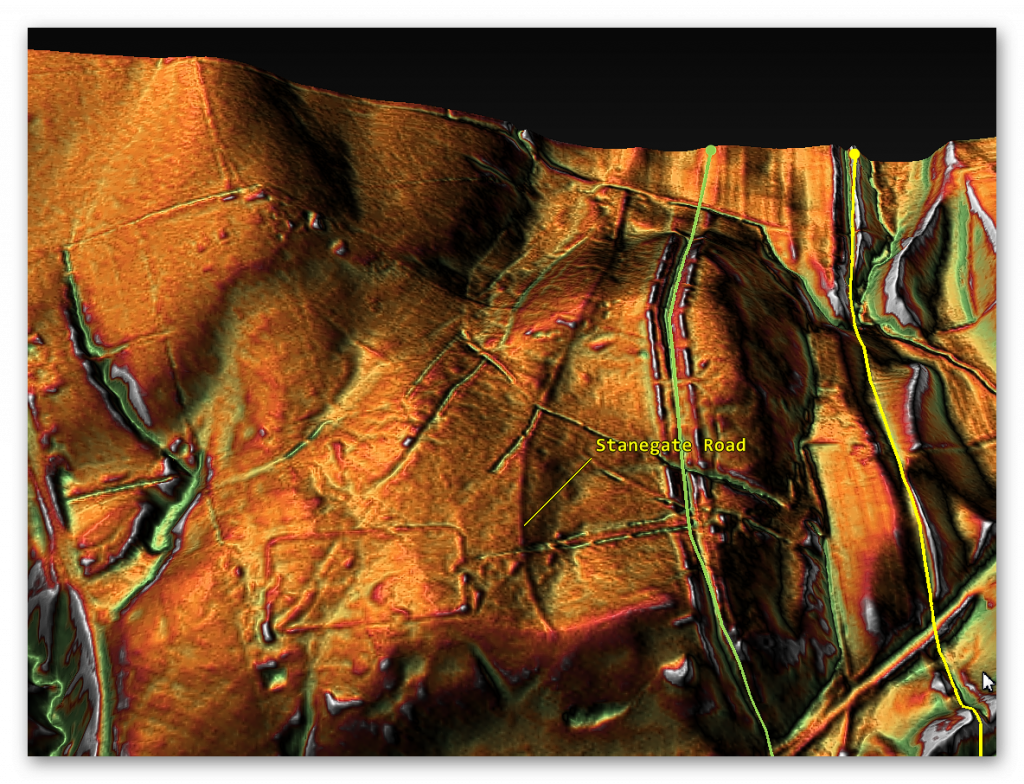

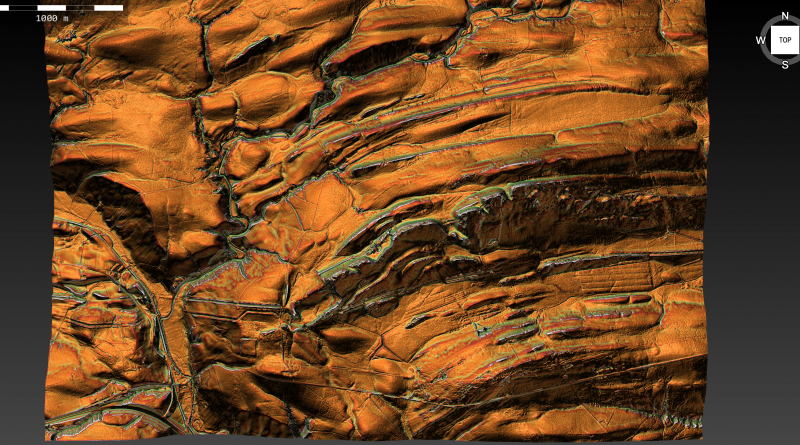

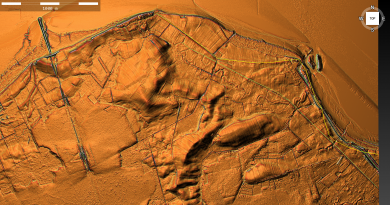

LiDAR Map

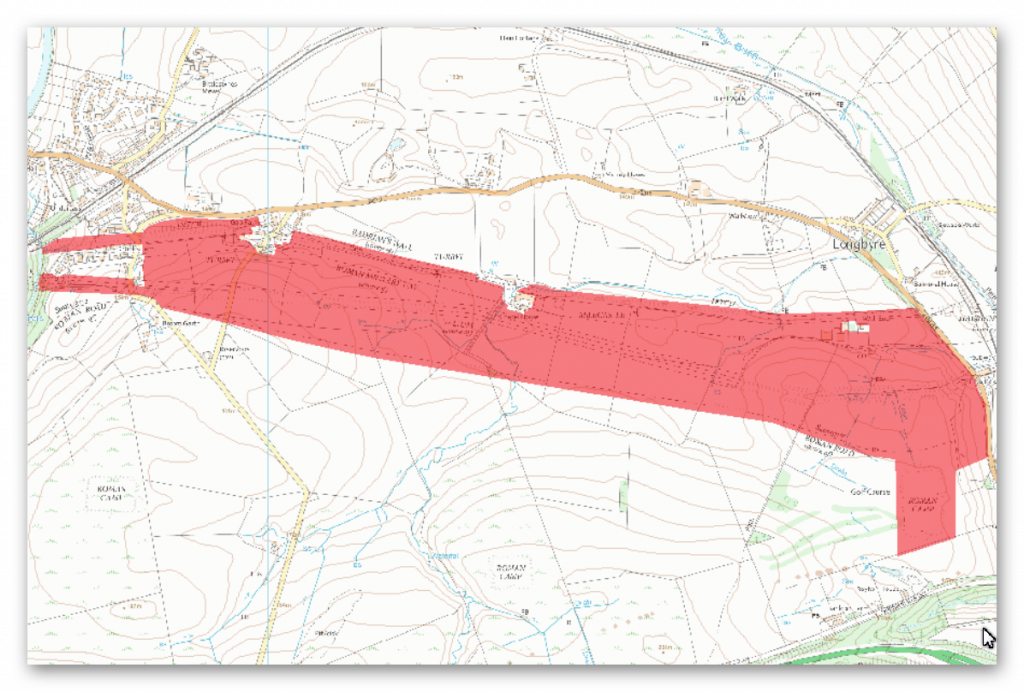

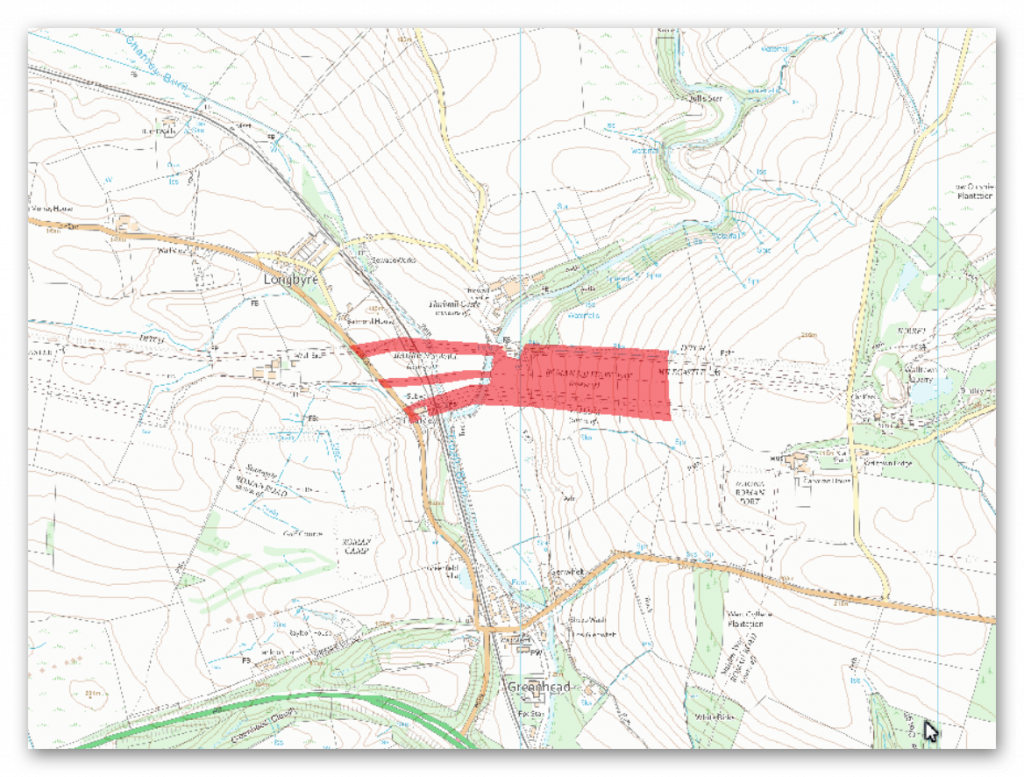

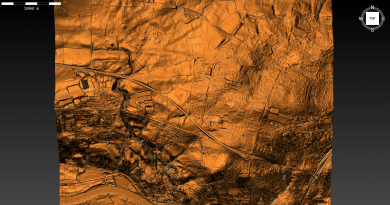

Google Earth Map

Historic England Scheduled Monuments within Section J

Name: Hadrian’s Wall, vallum, section of the Stanegate Roman road and a Roman temporary camp between the B6318 road and Poltross Burn in wall miles 46 and 47

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010993

Name: Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between the field boundary west of Carvoran Roman fort and the west side of the B6318 road in wall mile 46

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010992

Name: Carvoran Roman fort and Hadrian’s Wall and vallum between the unclassified road to Old Shield and the field boundary west of the fort in wall miles 45 and 46

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010991

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between Walltown Quarry East and Walltown Quarry West in wall mile 45

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010977

Name: Hadrian’s Wall between the track to Cockmount Hill and Walltown Quarry East in wall miles 43, 44 and 45

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1017535

Name: The vallum between Cockmount Hill and Walltown Quarry West in wall miles 43, 44 and 45

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010978

Name: Great Chesters Roman fort and Hadrian’s Wall between the Caw Burn and the track to Cockmount Hill farm in wall miles 42 and 43

Designation Type: Scheduling

Grade: Not Applicable to this List Entry

List UID: 1010976

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and vallum and their associated features between the B6318 road in the east and the Poltross Burn in the west. All the upstanding remains of Hadrian’ Wall and the milecastle in this scheduling are Listed Grade I. Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout this section except for a short section of Wall less than 10m long which was excavated in 1957 ahead of road widening.

The Wall here is consolidated and of broad wall foundation, 3.3m wide and up to 0.5m high. Between this section and milecastle 47 the Wall can be traced as a turf covered scarp measuring 3.5m wide and 0.4m high. A modern wall partly overlies this scarp. West of turret 47b the remains of the Wall are again visible as a turf covered scarp, 0.4m high, with a field wall occupying the centre line of the Wall. In the woodland above the east bank of Poltross Burn the Wall survives as a bank of tumbled stone which has a maximum height of 0.5m. Elsewhere the Wall survives as a buried feature with no remains visible above ground, being overlain by a field wall for most of its course. At Chapel House, farm buildings overlie the course of the Wall. As archaeological remains have not been confirmed to survive here this area is not included in the scheduling. The wall ditch survives intermittently as a feature visible on the ground. Where extant it averages 2m deep, but elsewhere it is silted to varying degrees and in some sections there are no surface traces.

The upcast mound from the ditch, usually referred to as the glacis, survives as a ploughed down feature to the north of the ditch in parts of this section. Milecastle 47 is situated about 250m east of Chapel House. It survives as a slight turf covered ploughed down platform. Dressed stones from the gate lie to the north on a modern causeway across the wall ditch. Excavations in 1935 uncovered large barrack blocks either side of the central space within the milecastle. An oven was found in the north west corner. This milecastle measures internally 21.2m north to south by 18.5m across. The exact location of turret 46b has not yet been confirmed. On the basis of the usual spacing its remains would be expected to lie under one of the outbuildings of Wall End farm. No upstanding remains are visible above ground. As archaeological remains have not been confirmed to survive here, Wall End farm is totally excluded from the scheduling. The exact location of turret 47a has not yet been confirmed. On the basis of the usual spacing it is expected to lie about 220m west of Chapel House. The exact location of turret 47b has not yet been confirmed. On the basis of the usual spacing it is expected to be located beneath the house and garden of `Meadow View’. As archaeological remains have not been confirmed to survive here, The Gap, including `Meadow View’, is not included in the scheduling.

The exact course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and Vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is not known with certainty throughout the whole of this section. The only visible remains survive as a terrace in a north facing slope to the south and west of Wall End farm. Elsewhere it survives as a buried feature beneath the turf cover with few traces visible above ground.

The vallum survives as an intermittent earthwork visible on the ground in parts of this section. Elsewhere it has been ploughed down and its remains survive as buried features masked by the turf cover. In the area of Greenhead Golf Course the extant ditch survives up to 1.8m deep and the north and south mounds up to 0.8m high. Either side of the Poltross Burn the vallum ditch is visible on the rim of the gorge where it measures 0.6m deep.

The east-west Roman road known as the Stanegate, which was a pre-Hadrianic construction dating to the early 80s AD, survives intermittently in this section as a feature visible on the ground. Where visible it survives as a linear turf covered mound, 0.4m high. Elsewhere its remains survive as buried features.

A Roman temporary camp, known as Glenwhelt Leazes, is situated on Greenhead Golf Course. It is situated on the east end of a spur overlooking the gap in the Whin Sill escarpment cut by the Tipalt Burn. It survives as a series of earthworks visible on the ground. The defences are best preserved to the east of the north gateway where the rampart is up to 4m wide and 0.7m high and the outer ditch is 3m wide and 0.5m deep. This north facing rectangular camp measures 150m north to south by 80m across and encloses an area of 1.2ha. The four gateways are particularly significant in that each has both an internal and external defence bank and ditch visible on the ground. The interior has been ploughed and drained creating a levelled area.

The monument includes Hadrian’s Wall and vallum and their associated features between the field boundary west of Carvoran Roman fort in the east and the west side of the B6318 road in the west. All the upstanding remains of Hadrian’ Wall in this scheduling are Listed Grade I.

Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout most of this section with few remains visible above ground. Traces of it are visible at the east end of this section where it survives as a low spread mound with a maximum height of 0.3m. At the west end of the section between the railway line and the B6318 its course is marked by a robber trench. Elsewhere its remains are masked by the sediments of the floodplain.

The ditch survives well in this section as an earthwork visible on the ground except for the section across the flood plain where a low ploughed down mound occupies the line of the silted ditch. Where extant the ditch measures up to 3.5m deep at the east end and 1.6m deep at the west end. The upcast mound from the ditch, known as the glacis, survives well at the east end of this section as a broad, low turf covered mound to the north of the ditch. Elsewhere its remains are not visible.

The exact location of turret 46a has not yet been confirmed. However, on the basis of the usual spacing it is expected to be situated in the garden to the south west of Holmhead on the east bank of the Tipalt Burn. The turret remains will survive as buried features below the garden and are included in the scheduling.

The exact course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, has not yet been confirmed in this section. Its predicted course is shown on the current Ordnance Survey map.

The vallum survives as an earthwork visible on the ground at the east end of this section. The ditch has a maximum depth of 2.5m, but due to silting is on average 1m deep. The north and south mounds have been ploughed down and now average 0.3m high. Mound crossings are visible along this length. Elsewhere there is no trace above ground of the vallum on the steep ascent from the Tipalt Valley or across the flood plain. A slight depression marks the line of the vallum ditch between the railway and the B6318 road north of the Thirlwall View terrace of houses.

The monument includes the Roman fort at Carvoran and Hadrian’s Wall and vallum and their associated features between the road to Old Shield in the east and the field boundary west of Carvoran fort in the west. All the upstanding remains of Hadrian’s Wall and the milecastle in this scheduling are Listed Grade I.

Hadrian’s Wall survives as a buried feature throughout this short section. It is traced on the ground as a robber trench, seen as a depression in the turf cover, 2m wide. West of milecastle 46 the Wall remains survive as a low turf-covered stony mound, 0.3m high. The wall ditch survives very well as a turf-covered earthwork visible on the ground. It averages over 3m in depth throughout its length in this section. The ditch upcast mound, known as the glacis, to the north of the ditch also survives well in this section. It is visible on the ground as a substantial low mound, up to 10m wide in places. Milecastle 46 is situated just below the crest of a west facing slope overlooking the gap in the Tipalt valley. It was first discovered in 1807 by Lingard and rediscovered in 1910 by Gibson and Simpson. It survives as a faintly visible turf-covered platform, 0.3m high.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and vallum linking turrets, milecastles and forts, is known with a fair degree of certainty. Its remains survive below the turf cover. Although there is no surface trace, the space between the Wall and vallum is so confined that its course can be fairly accurately determined. The presence of crossings on the vallum north mound and the absence of breaks at critical points on the mound suggest that the Military Way was not on the north mound or the berm in this section.

The vallum survives as an earthwork visible on the ground throughout this section. To the north of Carvoran fort the vallum veers to the north to approximately 10m from the Wall before reverting to its previous alignment near Tipalt Burn, the deviation coinciding with the length of the larger earlier fort. The south mound has been largely reduced or destroyed by ridge and furrow cultivation. The ditch is mostly silted up in this section though it can be seen 0.4m deep in places. The north mound survives to the north of the modern wall to a height of 0.7m. There are five crossings visible in the north mound, though no traces of ditch causeways survive.

The Stanegate Roman road, which predates the Hadrianic frontier, ran east to west between Corbridge and Kirkbride respectively. It survives largely as a buried feature in this section, visible intermittently as a low ploughed down causeway. For most of its course however there is no surface trace. Its course is known from the first edition Ordnance Survey maps which depict it as a visible feature running parallel and to the immediate south of Carvoran fort.

The Maiden Way is a Roman road which ran north to south probably from the Stanegate outside Carvoran to at least as far as Kirkby Thore to the south. Its remains survive as buried features below the turf cover in this section. However, its course is known as it was marked on the first edition Ordnance Survey map as an upstanding feature. According to this map the junction of the Maiden Way and the Stanegate was to the south east of the south east corner of the fort. Carvoran Roman fort, known to the Romans as Magna, is situated near the crest of the steep west facing slope overlooking the gap in the Tipalt valley. It guards both this important gap and river crossing and also the junction of the Stanegate and Maiden Way.

The fort probably originates from the same period as the Stanegate, around AD 80, and was later included in the Hadrianic frontier, started in AD 122. It is not actually attached to Hadrian’s Wall, but lies about 220m to the south of the Wall and 160m south of the vallum. The stone fort is visible as a turf covered platform with some exposed masonry at the north west angle tower. This fort measures 135m by 111m over the ramparts, enclosing an area just under 1.5ha. Antiquaries who visited the site from 1599 onwards all record the presence of substantial buildings and streets within the stone wall of the fort. A bath house with plastered walls was observed within the south wall near the south west angle. Aerial photography has revealed the south west corner of a larger predecessor to the visible stone fort between the south west corner of the stone fort and the B6318 road. A faint crop mark running north-south observed south east of Carvoran House may also be associated with this large fort.

The Roman name, Magna, is not appropriate for the relatively small stone fort and suggests that it replaced an earlier larger fort. Further Roman ditches were located in 1985 east of Carvoran House which may belong to a third fort. The pre- Hadrianic history of Carvoran is clearly complex, with the possibility that, like Vindolanda, it consisted initially of a smallish fort which was replaced by one or more larger forts before the construction of the visible small stone fort. As there has been no organised excavation at this site most of what is known comes from chance finds across the site and aerial photography. A number of altars and inscriptions testify to the various detachments which were stationed at the fort at one time or other. These included Hamian archers from Syria and the first cohort of Batavians. Probably the most interesting find to date is the inscription on a stone tablet of a metrical hymn dedicated to the Virgin of the Zodiac, now in the Museum of Antiquities at Newcastle. A well within the fort yielded a set of stag’s antlers and an iron javelin head, both in very good condition. The civil settlement outside the fort, usually referred to as a `vicus’, was very extensive according to the accounts of the antiquaries who visited the remains.

Horsley, writing in 1732, states clearly that the remains of the vicus were located to the south and west of the fort. No visible remains of the vicus to be seen above ground today, but its remains survive as buried features. The vicus is also testified to, by the numerous dedications to the god Vitiris. A bronze measuring container, or `modius’, weighing 26 pounds was discovered in 1915 just north of the north east corner of the fort. It is inscribed and names the emperor Domitian under whom it was made. Domitian died in 96 AD, implying that the Roman occupation at Carvoran probably predated the Wall. The cemetery associated with the fort and vicus was located to the east of the fort around the Stanegate on its approach to the installation.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and its associated features between the two quarries at Walltown in wall mile 45. All the upstanding remains of Hadrian’s Wall and the turrets in this scheduling are Listed Grade I.

Hadrian’s Wall follows the crest of Walltown Crags in this section with commanding views in all directions. It survives well as an upstanding feature, a 410m section being consolidated and in the care of the Secretary of State. It stands to a maximum height of 2.2m. A number of inscribed stones, indicating which section of the Roman army built this stretch, were found fallen from the south face of the Wall during conservation work in 1960. The short stretch of Wall not exposed east of turret 45a survives as a low amorphous stony bank, 0.3m high.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, is known throughout this section. It is visible as a low causeway, 0.2m high, or as a terrace, 5m wide, winding between rock outcrops to the south of the Wall. Turret 45a is situated on a high point on Walltown Crags with extensive views in all directions. It survives as an upstanding exposed feature, which is consolidated and in the care of the Secretary of State.

The interior of the turret was investigated in 1883 and partly excavated in 1913. Further excavations in 1959 by Woodfield showed that it had originally been built as a free standing tower and was then later incorporated into the Wall line as a turret. It has a doorway in the south east side. Turret 45b was situated further west along the Nine Nicks of Thirlwall, but it has been completely destroyed by Walltown Quarry West which has removed the line of the crags in this area. Consequently this area is not included in the scheduling as no archaeological remains survive here. Excavations in 1883 prior to the destruction of the turret showed that it measured 3.95m north to south by 4.25m across internally. The walls were 1m thick and between 1m and 2m high.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and its associated features between the track to Cockmount Hill in the east and Walltown Quarry East in the west. All upstanding remains of Hadrian’s Wall, the milecastles and turrets in this scheduling are Listed Grade I.

Hadrian’s Wall survives mostly as a low stony rubble and turf covered mound throughout this section averaging 5m wide and 1m high, except for a few stretches of exposed upstanding masonry. At Cockmount Hill buildings overlie the line of the Wall. Between Cockmount Hill and milecastle 44 a modern field wall overlies the north face of the Wall where Hadrian’s Wall survives up to a maximum height of 1.7m. Here the south face is hidden below wall debris and is up to 1.3m high. West of Cockmount Hill a 50m stretch of unconsolidated Wall is exposed, up to 1.1m in height. West of milecastle 44 there are two sections of exposed Wall, 2.25m wide and standing 0.8m high. A short section of unconsolidated exposed Wall in a state of collapse is situated to the west of milecastle 45.

The Wall ditch seems to have been only partly completed west of Cockmount Hill before its full construction was abandoned. It is best preserved west of turret 43b where it has a depth of 2.2m with traces of the upcast mound, usually referred to as the glacis, on its north side. Along Walltown Crags the building of a ditch was unnecessary, except in the `nicks’ or gaps which break up the crags. The section north of `King Arthur’s Well’ survives up to 2m deep with the glacis 0.7m high to the north. Two shallower sections of ditch are visible in the two nicks to the east. Milecastle 44 is situated near the crest of an east facing slope with wide views to the north and south. Its walls survive as turf covered banks, 3.5m wide and 0.9m high.

A few facing stones are visible in the banks. The milecastle measures 20.3m north to south by 17m across. Excavation around the inner face of the milecastle walls is evidenced by the remains of robber trenches but it is not known when or by whom this was done. The road which connected the milecastle to the Military Way survives as a causeway 3.5m wide and 0.2m high. Milecastle 45 is situated on the crest of Walltown Crags with commanding views to the north and south. This milecastle survives as a turf covered feature. The walls are indicated by the remains of robber trenches flanked by spoil heaps. Large dressed stones from the gateway have been built into the low wall to the rear of the cattle trough east of Walltown farm. Turret 43b is thought to be situated on an east facing slope to the west of Cockmount Hill. Its exact location is yet to be confirmed.

Turret 44a is situated on the east end of a crag overlooking a nick to the east about 500m west of milecastle 44. It survives as a square turf-covered mound, 0.3m high. It was first located in 1912 by Birley. Turret 44b is situated at the east end of a crag overlooking the nick in which `King Arthur’s Well’ is located. It survives as an exposed stone feature. The inner face of the turret stands to a maximum height of 1.9m. Excavations at the turret were carried out in 1892 by Gibson who found a coin from the reign of Valens.

The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, is known throughout the length of this section. It survives as a low turf covered causeway 5.5m wide and up to 0.5m high, or as a terrace in the hillside with a minimum width of 3m. It is straight for most of its course except where it deviates around rock outcrops.

West of the Cockmount Hill Plantation the foundations of two large regularly laid out rectangular buildings overlie the Military Way, using it as a hard standing. Their form suggests they are post-medieval or later in date. South east of King Arthur’s Well a spur road branched off the Military Way, the remains of which can be seen as a turf covered causeway leading south east towards Lowtown.

An uninscribed Roman milestone is located along the line of the Wall west of Cockmount Hill. It forms the west post of the field gate at the west end of Cockmount Hill Wood. There is a series of five cultivation terraces on the slope to the south of Cockmount Hill Wood. They survive as turf covered earthworks. These cultivation remains run parallel with the contours on a south facing slope like the cultivation terraces at Housesteads which have been confirmed to be Roman. Later narrow ridge and furrow, on average 2.5m apart, overlies some of these earlier terraces.

The monument includes the section of vallum between Cockmount Hill in the east and the west side of Walltown Wood in the west. For most of its length the vallum survives as an upstanding earthwork.

However, south of Allolee where its remains are not generally visible above ground, traces have recently been identified by the Royal Commision on the Historical Monuments of England. The presumed course as shown on Ordnance Survey maps is thus now known to be incorrect.

The scheduling respects the new known alignment here. Where it survives as an earthwork the vallum ditch averages 1m deep with a maximum depth of 2.7m in places. The north mound averages 0.8m high and the south mound 0.4m. Good examples of crossing points positioned at 37m intervals are visible throughout this section.

Where the ditch was cleaned out during the Roman period a marginal mound, formed of the removed ditch silts, was built up in places. It survives intermittently in this section, averaging 1m high. South of Allolee Farm ploughing has reduced the vallum earthworks to slight undulations. The ditch here is completely silted up.

An excavation trench was cut across the vallum in 1939 by Simpson and Richmond at Cockmount Hill, but the precise location of this trench is not known. This work indicated that a causeway across the vallum was revetted with turves, and that the sides of the ditch had already weathered back prior to the building of the causeway, indicating that the building of the causeway was later. The area of vallum within Walltown Woods is situated on a spring line with drainage channels cut across the banks. Otherwise it survives well in the woodland.

The monument includes the section of Hadrian’s Wall and vallum and the Roman fort at Great Chesters and their associated features between the Caw Burn in the east and the track to Cockmount Hill farm in the west. All the upstanding remains of Hadrian’s Wall, the milecastle and turrets are Listed Grade I.

Hadrian’s Wall survives as a low stony mound throughout much of this section. It is visible as a turf-covered scarp 0.2m high with a modern field wall overlying its course. The farm buildings at Great Chesters east of milecastle 43 partly overlie the Wall in this area. West of Great Chesters fort the course of the narrow wall survives as an amorphous rubble strewn mound 3m to 4.8m wide and 1.1m high. In addition the line of the broad wall here survives as a separate north facing scarp. Excavations here in 1925 revealed that the narrow wall runs south of the broad wall foundation from Great Chesters as far as turret 43a where they converge. Beyond turret 43a they run parallel again as far as Cockmount Hill Wood where their courses again converge. To the west of Burnhead camp a section of unconsolidated exposed Wall, 38m long and 1.8m wide, stands between two to six courses high being up to 1.5m high on the inner face.

The wall ditch survives a visible earthwork throughout most of this section. It averages between 0.8m and 2m in depth with near vertical sides in places. Large boulders protrude from the scarps intermittently along its length. The ditch at Great Chesters is overlain by farm buildings which are excluded from the scheduling, although the ground beneath them is included. The ditch is not visible either side of turret 43a, suggesting that it has silted up leaving no trace on the surface. The ditch upcast mound, usually referred to as the `glacis’, survives to the west of Great Chesters fort as a broad low mound, 0.3m high and 8m wide, on the north side of the wall ditch. Milecastle 43 is situated on a ridge later occupied by the fort of Great Chesters which commands views to Chesters Pike in the north, the Stanegate Roman road to the south and the Caw Burn to the east. The milecastle survives as a buried feature below the turf cover. It was located during excavation at Great Chesters in 1939 by Simpson and Richmond. Turret 42b is situated on a gentle east facing slope to the west of the Caw Burn. It survives as an uneven turf-covered platform, up to 0.6m high. The surface remains show evidence of digging and stone robbing. The turret was first located in 1912 by Simpson. Turret 43a is thought to be situated about 150m east of Cockmount Hill farm. There are quantities of wall debris strewn over the grass-covered bank of the Wall at this location which may obscure any slight surface remains of the turret.

The site of the turret was first suggested in 1912 by Simpson, but its position has not yet been verified. The course of the Roman road known as the Military Way, which ran along the corridor between the Wall and the vallum linking the turrets, milecastles and forts, survives intermittently as an upstanding feature throughout this section. Its course from the Caw Burn is known where it survives as a low turf-covered mound, 6m to 8m wide and 0.2m to 0.5m high. Occasional sections of this low turf-covered causeway reappear on the line up to the east gateway of Great Chesters fort. Beyond the field boundary west of the fort the Military Way is visible again as a discontinuous terrace with a slightly sinuous course which avoids the rock outcrops. Field gates are positioned on its course at the east and west end of this stretch. A road linking the Military Way and the Stanegate Roman road to the south via Great Chesters fort is overlain by the modern trackway to Great Chesters Farm which enters the fort through the south gateway.

The vallum survives as an upstanding earthwork in the west half of this section, but in the east half it is only recognisable as an intermittent mound and ditch and by occasional discolourations in the vegetation. In the west half of the section the north mound averages 0.8m high, the ditch 0.5m to 0.9m deep and the south mound 1.2m high. Here crossings of the vallum are still to be seen at approximately 37m intervals. An excavation trench was cut across the vallum in 1939 by Simpson and Richmond at Cockmount Hill, but the precise location of this trench is not known. It was revealed that a causeway across the vallum was revetted with turves, and that the sides of the ditch had already weathered back prior to the building of the causeway, indicating that the causeway was later.

Between Great Chesters fort and turret 43a are the remains of three separate shielings abutting the south side of the narrow wall, which survives here as a turf-covered mound. The shielings are visible as turf-covered dry stone foundations. Their walls measure between 0.6m and 2.1m wide and up to 0.3m high. Shielings are small shepherds’ huts usually associated with upland grazing during the summer months. They are characteristic of the medieval period in this area. Great Chesters Roman fort, known to the Romans as Aesica, is situated on a low ridge overlooking the Caw Burn to the west. It measures 129m by 109m across its ramparts and encloses an area of 1.36ha. It was one of the last forts to be built, being attached to the rear of the Wall, like Carrawburgh, and was completed between AD 128 and AD 138. It is visible as a series of upstanding turf-covered remains.

The most obvious features are the turf- covered ramparts and the defence ditches, there being no less than four on the most vulnerable west side. The buildings of Great Chesters farm overlie the north east corner of the fort. There have been a number of excavations of the fort, all of which have now been backfilled leaving amorphous mounds and depressions on the ground surface. These excavations have recorded the remains of the headquarters building, commanding officer’s house, barrack blocks and lean-to structures against the inside of the fort walls. A vaulted chamber was discovered in the headquarters building which is on display in the centre of the fort. The west tower of the south gate has yielded an important hoard of jewellery which includes an enamelled brooch shaped as a hare and a gilded bronze brooch considered to be a masterpiece of Celtic art. A number of stone ballista balls were found beside the north west angle-tower when first excavated in 1894. A number of building inscriptions have also been discovered.

Traces of the civil settlement outside the fort, usually referred to as the vicus, have been identified to the south and east of the fort. Horsley, writing in 1732, mentioned that, `the outbuildings are most considerable to the south side….there are vast ruins of buildings in this field’. There is a series of building platforms terraced into the slope to the south east of the fort either side of a long scarp running from the south east corner of the fort to the bath house. The most prominent platform contains a section of upstanding exposed walling. The field to the south of the fort has been ploughed for many years and there are no upstanding features visible except for a slight platform close to the field wall south of the fort. However, bearing in mind the examples of the better known vicus sites at Housesteads and Vindolanda it is expected that the vicus remains at Great Chesters will survive as buried features in the field to the south of the fort and possibly more extensively. The remains of a bath house 110m due south of the south east angle of the fort were visible until the end of 1987 when they were back filled to the surrounding ground level by English Heritage to avoid further deterioration. The bath house was excavated in 1897 by Gibson and again in 1908 by Simpson and Gibson. The excavations showed that it conformed to the usual design of military bath houses with the various hot, cold and intermediate rooms, together with furnaces, flues and a hypocaust system. It survives as a buried feature.

The exact location and extent of the cemeteries directly associated with this fort are not yet confirmed with certainty. There are two cemeteries to the south of the vallum; one at Wall Mill and one at Four Laws, both of which are the subject of separate schedulings. However, a burial mound is located approximately 240m south west of the fort. This round burial mound is similar in form to burial mounds found near Housesteads and Vindolanda. Together with a number of inscribed tombstones found during excavation of the fort interior it seems that there was a cemetery associated with Great Chesters to the south of the vicus and north of the vallum in addition to the known cemeteries at Wall Mill and Four Laws.

There is a series of cultivation terraces running parallel with the contours approximately 350m west of the fort. There are at least six terraces identifiable in this group all of which survive as upstanding turf-covered earthworks. They are directly comparable to the examples at Housesteads which have been confirmed as Roman in date, which like these are also situated on a south facing slope. Some of these cultivation terraces are overlain by post- medieval narrow ridge and furrow indicating a succession of land use in this area over time.

Investigation

There are many strange aspects to the Vallum in this section. The most obvious problem is the strange ‘Kink’ that looks like a recut of the original pathway into a mining quarry. From the east it disappears into the river valley as seen on previous sections to reappear out of the river valley and turn NE, go straight again (West) the turn SE to disappear into a massive quarry. Is this a indication to the Vallums purpose?

The Vallum in this section is associated with the lower land and river valley for most of its course, so much so, that to the west the Vallum is at a base of a hill that would make it incredibly vulnerable to attack from either the north or south.

The other anomalies that are claimed are the Military Way and Stanegate Roads. The Lidar shows them to not be quite what would be expected.

Stanegate on the Western Section of this sector comes out of a river valley then heads towards the Roman Camp but at the last minute heads away down to another river valley disappearing again?

What we find from the LiDAR maps is that there is absolutely no real evidence of Military Way – which is reflected in the fact that it doesn’t exist in the original large scale OS maps and was added in the 1920’s as a theory with real archaeological support as we now see – this is the same in both East and West of this 5km section of the wall.

As for Stanegate Road – after it missed the Fort and went into the River Valley (although OS maps have continuing to the next Fort in the area – LiDAR catches it coming out of the River Valley AFTER the Fort and then going off East.

To understand the problem with Hadrian’s Walls history read our article HERE.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Pingback: Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation - Prehistoric Britain