The Old Sarum Hoax

This week we that a look at The Old Sarum Hoax

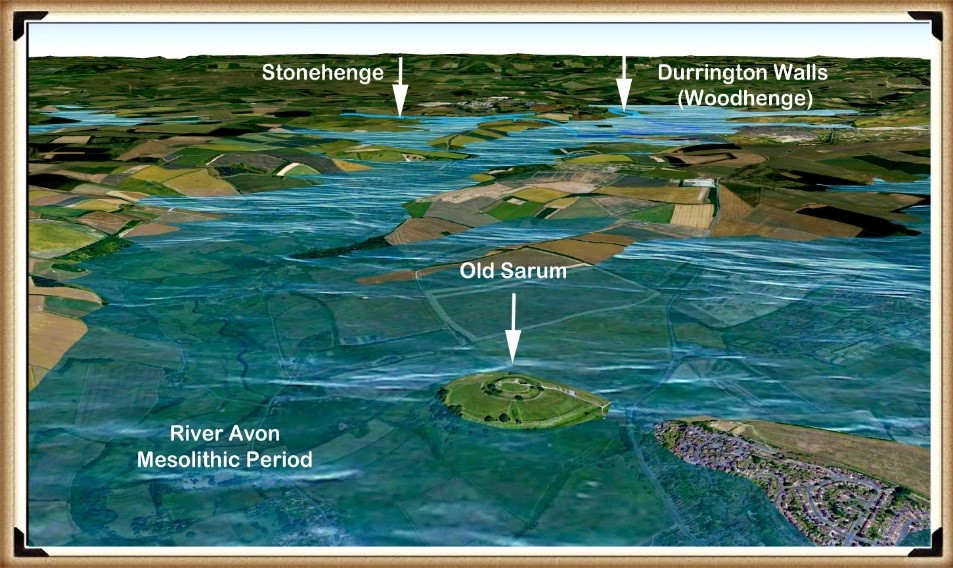

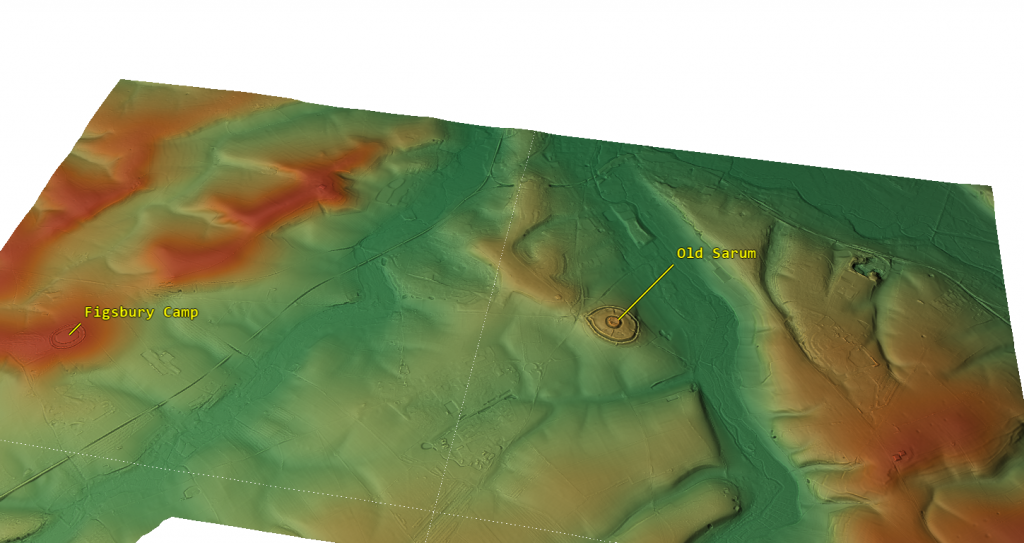

If we use the Southern Station Stone as a direction marker from Stonehenge, it points South by South East. If we then follow the line on a map of our Mesolithic landscape, showing the raised river levels of the past, we find that it points to a fantastic site just 10 km away from Stonehenge: an island in the middle of an extensive waterway called Old Sarum. (The Old Sarum Hoax).

The positioning of this site is most interesting, as it lies very close to the English Channel, which would have taken boats off to the continent. It is quite possible that this was Britain’s first seaport, as it seems to be the last known occupied Mesolithic island. If so, it would have been one of the most critical sites in Britain and Europe, as it would have been involved in nearly all Mesolithic imports and exports to and from France, Spain and the Mediterranean countries.

The area surrounding Old Sarum is also of great interest as it has two sites on the same raised rivers of the Avon in the past. One of these sites shows that it was even older than Old Sarum, and it’s called Figsbury Ring. The Old Sarum area is very similar to the Avebury Area as it has an ancient site older than the central Avebury Stone circle called Windmill Hill.

Both Windmill hill and Figsbury are what archaeologists call ’causewayed enclosures’ – this is sadly and not uncommonly incorrect labelling of these sites by academics as we also see from their term ‘Iron Age Forts’ that are neither not Iron Age nor fortifications.

Causewayed enclosures are labelled so as archaeologists perceive them to be enclosures for cattle and paths across the ditches (causeways) for access by the livestock – this is complete nonsense.

A more historically accurate definition for these monuments would be ‘concentric circle sites’ – the term was created by none other than Plato referred to them back in 300 BCE when relating to the story of Atlantis and its central city’s description – which I cover in great depths in my books.

This ancient referral to such sites clearly dates both Windmill Hill and Figsbury to the very early Neolithic, when the Avon and Kennet waters were at their highest directly after the last Ice Age 12k years ago.

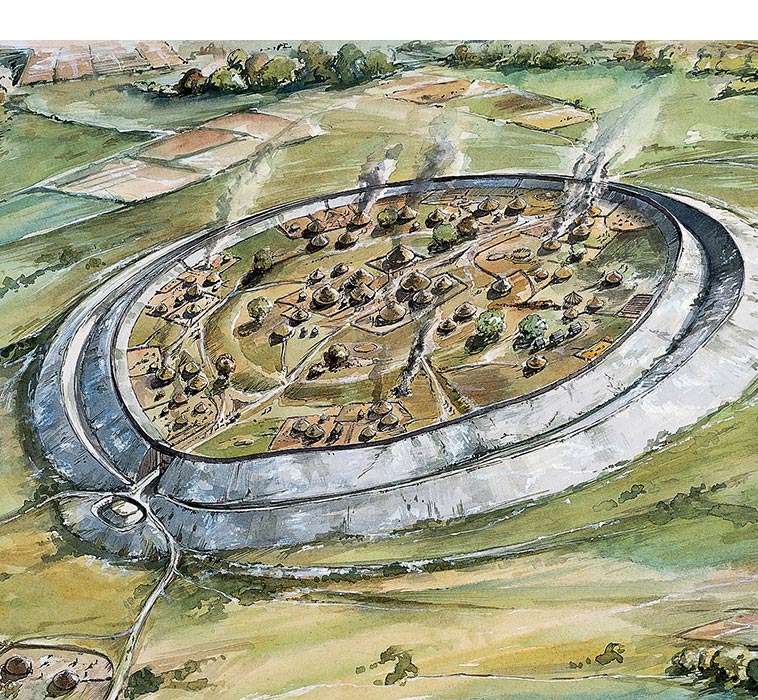

These monuments were constructed for boats to moor with their circle ditches to trade, and it was only when the waters fell towards the end of the Mesolithic and early Neolithic that both Old Sarum and Avebury were constructed to replace their predecessors.

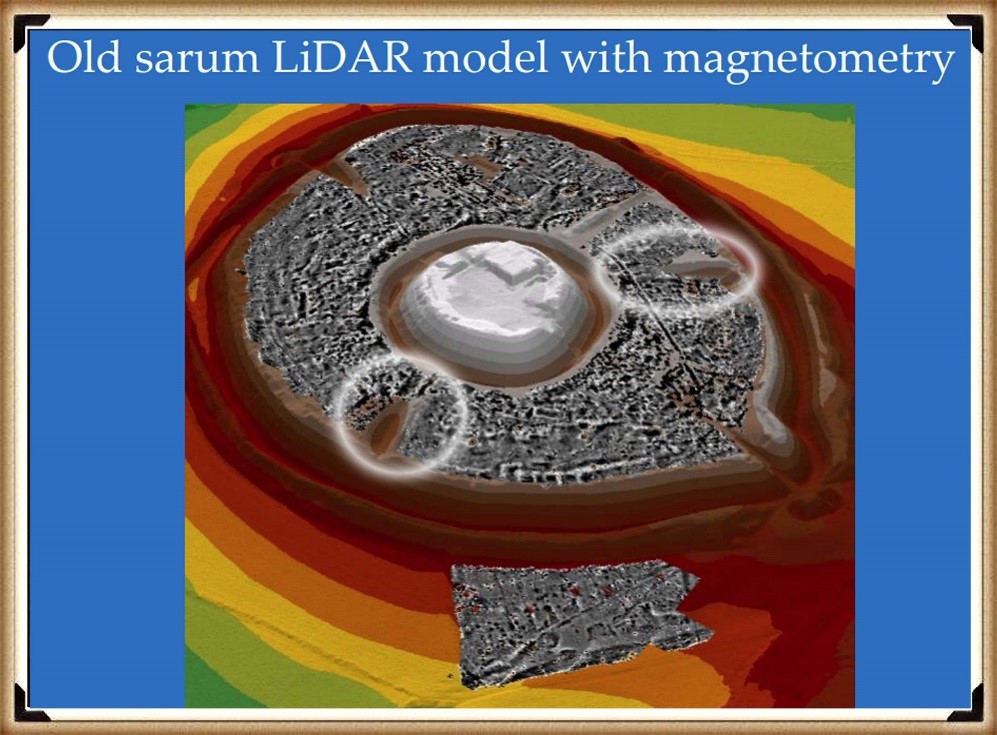

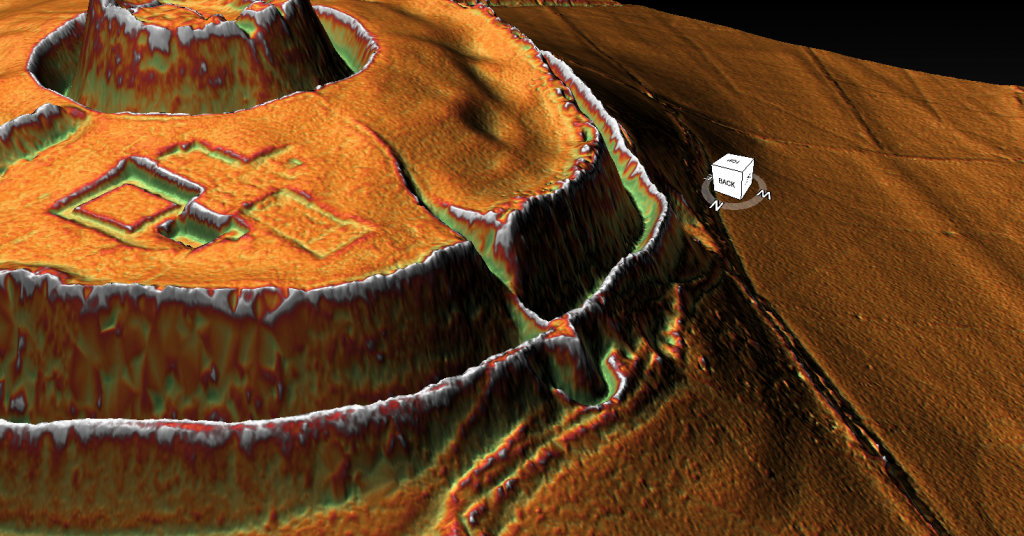

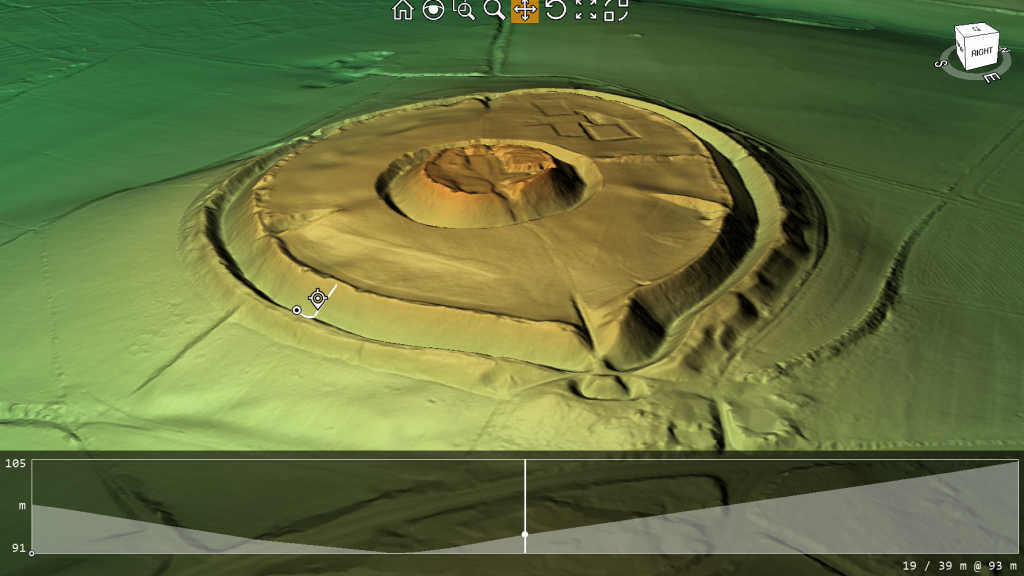

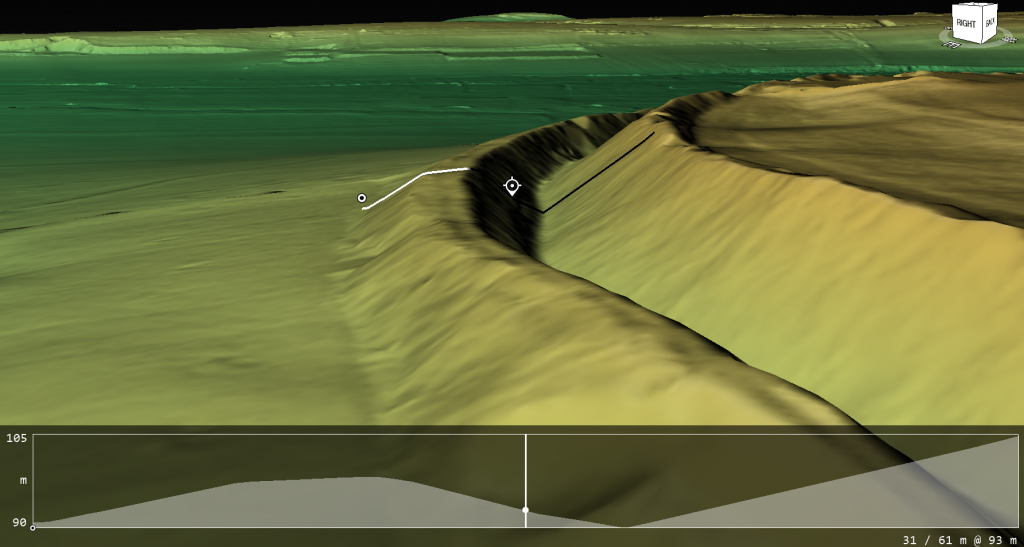

The island of Sarum would have been a magnificent sight, sitting in a vast river as wide as the eye could see. When we look at the LiDAR survey of the site, we notice that two deep ditches lead from the outer to the inner ditch, both of which have been partially filled. During the Mesolithic, the groundwater would have flooded both the outer and inner channel via the Dykes (canal) cut in between the two ditches.

Current theories on this site speculate that the central moat was dug for the motte-and-bailey Norman castle that stands there today. Still, without firm evidence, this is just speculation – although as the centre of the site is now raised, it would be probable that both the Romans and then the Normans, cleaned out the prehistoric ditch and then extended further down to the new water table, to keep the inner ditch as a defensive moat, placing the excess spoil in the inner area of the site.

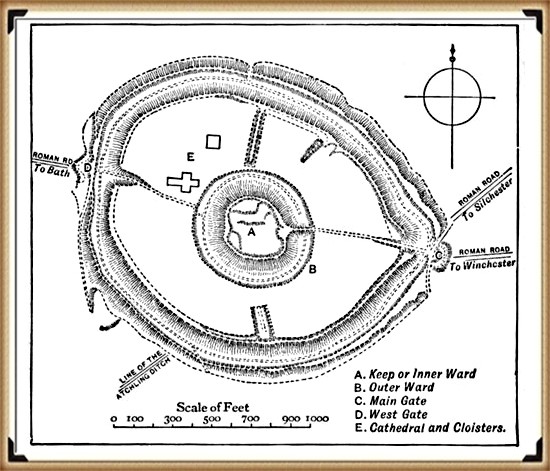

The site at Old Sarum is much bigger than Stonehenge and is similar to Avebury. One can only guess what would have been in the centre of the Mesolithic island. From the amount of reused Sarsen stone found in the remains of the Norman castle the original cathedral and the Roman Fort, we can infer that a megalithic structure like Stonehenge or Avebury stood at Sarum during prehistoric times. Because if you extend a line from the centre of the motte-and-bailey at Old Sarum through the centre of the church (the original Salisbury Cathedral), it points to Stonehenge.

Churches built on prehistoric sites are not uncommon. In addition, there are many instances of pagan religions being crushed by Christianity taking over their sacred sites and using the stone circles as a building material for their churches. So, we believe that in prehistory, three stone circles existed at Sarum: one large outer circle and two smaller inner circles, indicating the way to Stonehenge. Later, as the groundwater fell, our ancestors built Sarum’s outer banks to keep their sacred site an island. At Avebury, a similar configuration can be seen, with two smaller stone rings inside the large ring that borders the outer moat.

In the Neolithic Period, the groundwater table dropped by about 10 m, and the island of Sarum was joined to the mainland by a peninsula. Our ancestors, therefore, built giant ditches 12 m deep to keep the site surrounded by groundwater. The Southern and Northern mooring points could no longer be used, as the groundwater had receded too far, so the Neolithic people created a new landing point to the West. They left a gap in the large ditch, so that people and goods could enter the island; this would have looked like a bridge across the water.

At the end of this footpath, they built another mooring station that protruded from the edge of the moat-like a peninsula so that boats could be moored safely around the feature. (Silbaby)

For some bizarre reason known only to early archaeologists, the platform is shown on some maps as a Roman road which connected to a road some 200 metres away on the island’s West side. But, unfortunately, that theory would take a leap of faith and nature. As the landing platform, which is shown as a lumpy protrusion on maps, has a 1:2 slope with a vertical drop of over 30 metres. I would suggest that a Roman horse and cart would not be an advisable means of transport for this terrain unless they were equipped with ABS brakes and a parachute.

The historical record gives us some clues to Old Sarum’s deeper past and how the groundwater surrounding the island dictated its history. The original Salisbury Cathedral was built here, only to be moved down to the valley a few hundred years later. Can you guess the reason for the move? That’s right, the lack of water! It seems that even over the Cathedral’s brief history at Old Sarum, the groundwater continued to subside. As this story is well known, why did no one wonder how deep the rivers might have been thousands of years ago?

The Maths

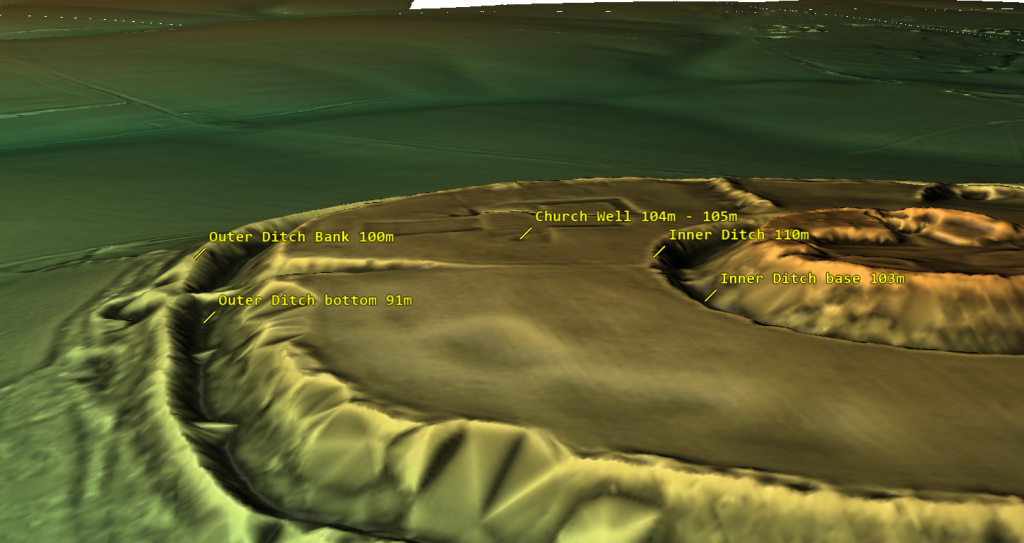

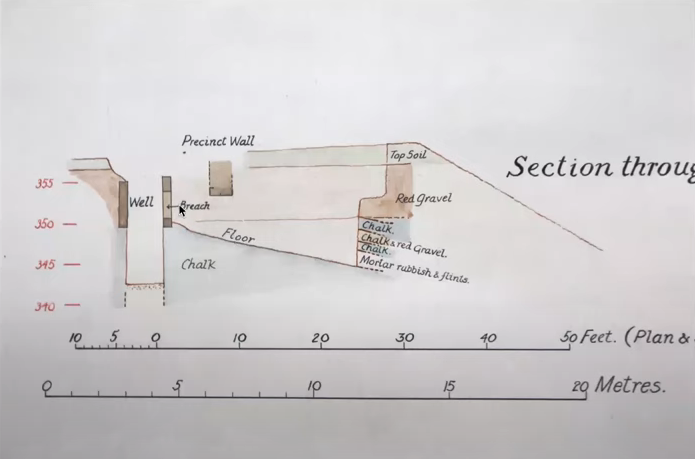

Currently, the groundwater table around Old Sarum is 56.5 m above sea level. The well in the Norman fort is 70 m deep from an altitude of 130 m, which shows that the groundwater is today 3.5 m below the Norman well. Therefore, the groundwater table in 1000 AD – when the well was first constructed – must have been at least 60 m, so in 1,000 years the groundwater has fallen 3.5 m. If we multiply this thousand-year drop in the groundwater table by 9, then add 56.5 m to account for the existing groundwater table, we can estimate the groundwater table 9,000 years ago, i.e. in 7000 BC. That would make the groundwater table (9 x 3.5 m) + 56.5 m = 88 m.

I the outer banks of Old Sarum are 89 m above sea level – close enough to prove my point methinks?

New information 2024

According to English Hertitage who own the site: Old Sarum is an ‘Iron Age hillfort’ may have been established here about 400 BC. It was then occupied shortly after the Roman conquest of Britain (AD 43), when it became known as Sorviodunum.

Three Roman roads from the north and east converged outside the east gate of the hillfort, and two sizeable Romano-British settlements were also established outside the ramparts. Little is known of this period, though it has been suggested that in the early Roman period a military fort was set up within the earthworks, with a civilian settlement outside. The civilian settlement formed the nucleus of one, or both, of the extra-mural Roman settlements. As the need for a fort dwindled, meanwhile, the area within the ramparts was converted to become the precinct for a Romano-British temple.

We have no evidence of the fate of Sorviodunum at the end of the Roman period, and the Anglo-Saxon period as a whole is poorly recorded. In 1003, however, a mint was sited within the old hillfort; and archaeological finds suggest there was late Anglo-Saxon settlement outside the ramparts. So there is evidence of life in and around Old Sarum before the Conquest.

In my view, oversimplified interpretations of the past, lacking excavation work to substantiate theories, pose significant challenges. Close examination often reveals fundamental flaws, such as the assumption of Roman roads converging and passing through a particular site. This type of desk-based archaeology, relying solely on OS maps and rulers, can lead to subjective conclusions.

The reality, as demonstrated by my own LiDAR investigation, contradicts these assumptions. The supposed road leading through the site to Bath is absent from both LiDAR maps and satellite photographs. Furthermore, considering the topography, it would be implausible for such a road to exist unless it were the largest land bridge in British Roman history.

It’s crucial to approach archaeological interpretations with a critical eye and to rely on comprehensive research methods to uncover the true complexities of the past. My LiDAR investigation highlights the importance of utilising advanced technologies and conducting thorough fieldwork to refine our understanding of historical landscapes.

Is it a defensive structure?

In archaeology, I believe honesty is paramount. Categorising sites under broad labels like “Iron Age Forts” oversimplifies their complexities. Take Old Sarum, for instance—it’s situated in a floodplain on an island, not on a hill as commonly assumed. This challenges our traditional understanding of fortifications and prompts us to reconsider our interpretations.

The proximity of these supposed defensive forts raises another intriguing question. Why would communities invest considerable time and effort in building multiple forts close to each other? Considering the logistical challenges and the likely limited population of prehistoric Britain, it’s logical to question the necessity of such clustering.

Assuming that manpower was an unlimited and cost-free resource in ancient times is overly simplistic. It overlooks the practical considerations that would have influenced decision-making. By challenging these assumptions, we can gain a deeper understanding of prehistoric society. I believe it’s essential to critically examine these aspects of the past rather than accepting naive interpretations. Let’s strive for a more nuanced understanding that acknowledges the complexities of ancient societies and avoids oversimplification.

Outer Moat constructed to keep in water as a moat?

When we examine the site’s profile using lidar, two major findings become apparent. Firstly, the spoil from the ditch was placed on the outside rather than the inside (as expected if it was defensive), and the base of the spoil was not part of the natural rise of the floodplain, indicating that the outer part of the ditch is actually a bank.

Water Table

Based on the site’s historical records, we understand that one motive for relocating the church was its water shortage, leading it to tap into the deep well owned by the garrison. This knowledge allows us to assess the state of the moats and comprehend why the inner moat was excavated to a depth of 7 meters. By examining the well discovered during excavation, we ascertain that it was abandoned at a depth of 104m to 105m meters (OD), suggesting that any ditch below this level would have become waterlogged.

The initial depth of the inner ditch was 110 meters (OD), but today it measures 103 meters (OD), which is below the bottom of the Church well. Based on this data, we can scientifically hypothesize that during Norman times, the inner ditch was dug deeper to reach the water table level. It’s also possible that as the water supply for the moat decreased over the church’s lifetime, the moat was excavated unusually deep to access the diminishing water levels.

This new understanding of the water table also opens up the possibility that the outer ditch was also moated up to the Norman conquest and moreover, during the Roman period – this is something that needs urgent explaination and further study.

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.