Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

Contents

Promotional Video – Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke

Extract From Book……………………… Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals)

The INTRODUCTION

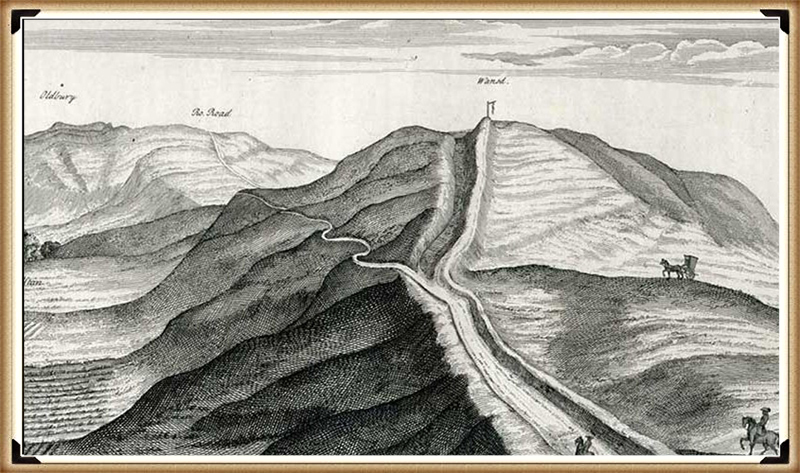

Wansdyke has always captured the imagination of the general public as it is a substantial prominent structure in the Wiltshire landscape relatively close to another famous ancient site Avebury, which also has massive ditches like Wansdyke and therefore, one might suggest there is a direct relationship between the two.

This apparent connection has not occurred to past or present archaeologists who sought to find a simple meaning for this unique ‘linear structure’ and hence the conclusion that it was built to defend warlike invaders of the past and hence a ‘Saxon’ name was adopted as historians of the past believed that these ‘tribes’ had large armed forces that could cope with such grand engineering undertakings as it was to defend their land.

Over the last few decades, this ‘fact’ (which was also shared by an even more immense ‘Dyke’ also named after a Saxon ‘Offa’) has been revisited and found that this continuous defence ditch is far less continuous than previously believed and a new theory developed for these earthworks as ‘Boarder Markers’ in the landscape – as they have never been a single body found with battle wounds in all 22 miles of Wansdyke or the 177 mile Offa’s Dyke which would support the defence hypothesis.

Sadly, even with this new ‘reassuring’ suggestion for these extensive sites, archaeologists have failed to address the facts that Dykes are incomplete and not continuous (Offa has 40% missing and Wansdyke has 20% missing) and there beginning and end points just ‘appear’ without reason in the landscape ‘like magic’ with no one able to tell you why.

Moreover, if these ‘Boundary Markers’ taking years if not decades to build were demarcation points for land ownership, then why do some Dykes (like Offa) track much larger separation points like major rivers that would have been a far more apparent marker than a 4m ditch and a known and well used territorial boundary marker still used today.

Furthermore, archaeologists have ignored that there are over 1500+ scheduled Dykes in Britain (including Ireland), of which 90% could not be used for this function as some of these ‘boundary markers’ are found on uninhabited islands dotted around the entire circumference of Britain.

Robert John Langdon (2022)

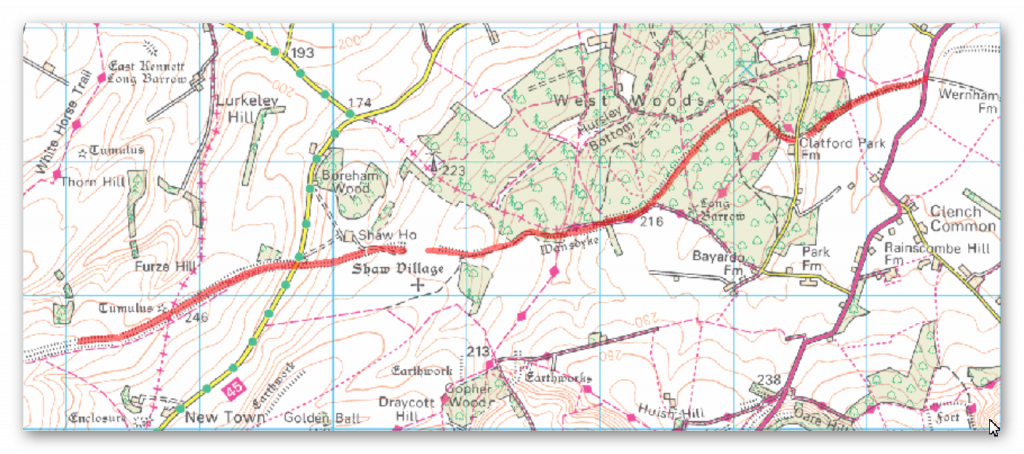

Section 2 – HE:1004719 Wansdyke: Section from S of Furze Hill to Marlborough-Pewsey Road 4.3km (4,300m = 12,900 working days – 20 men taking 649 days (1.78 years).

No, Historic Details or Excavations Registered

OS Map

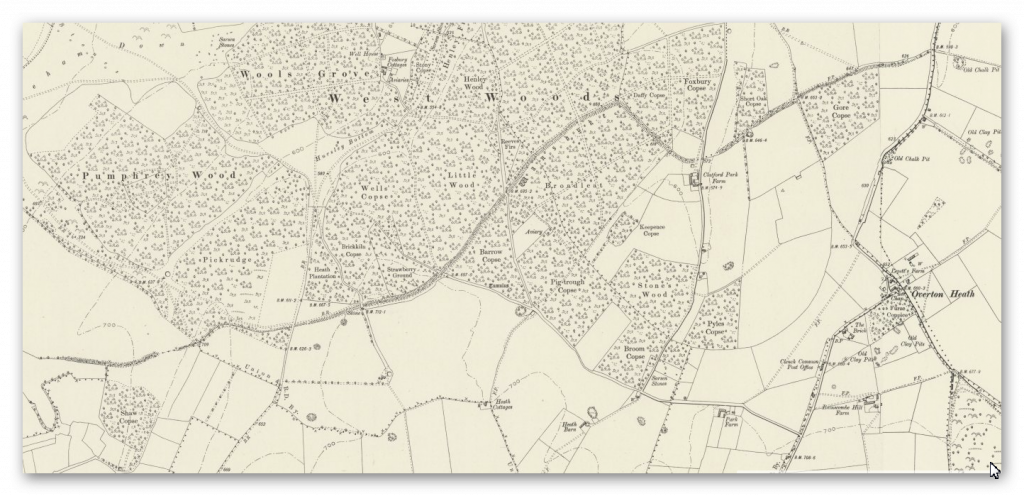

1800 OS Map

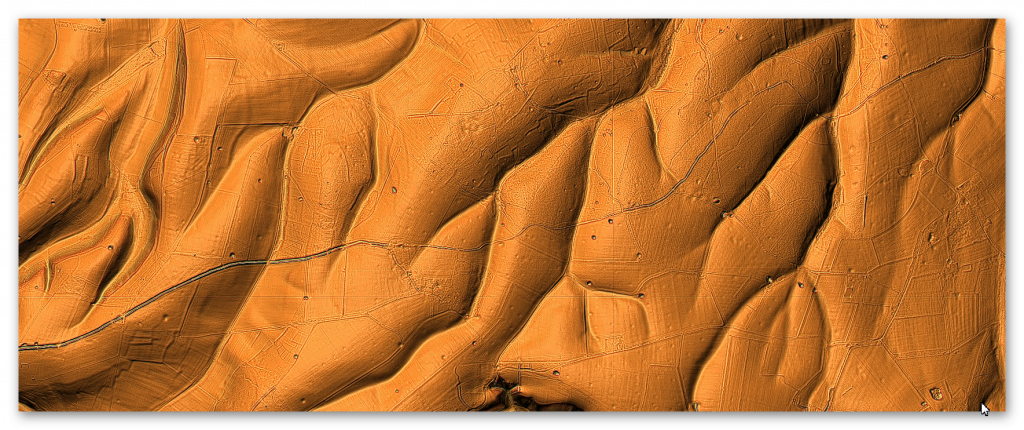

LiDAR Map

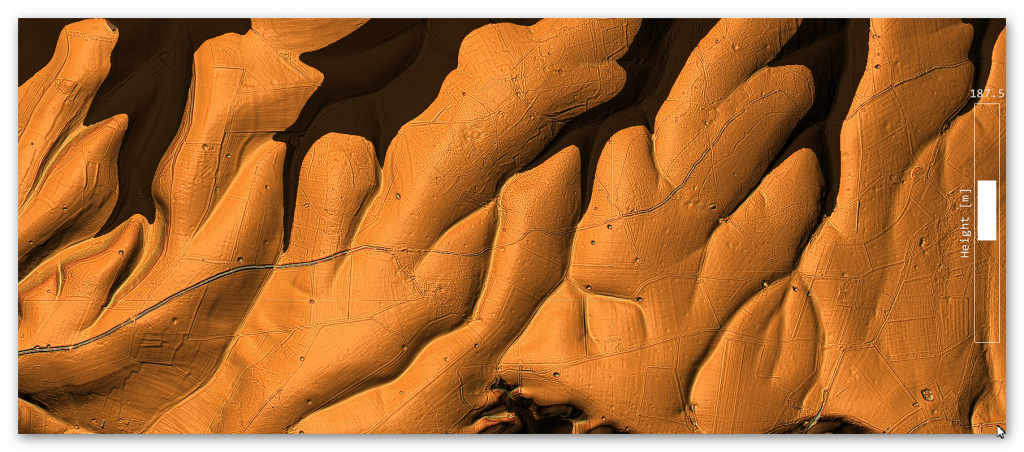

LiDAR (with Mesolithic water levels)

Canal working hours

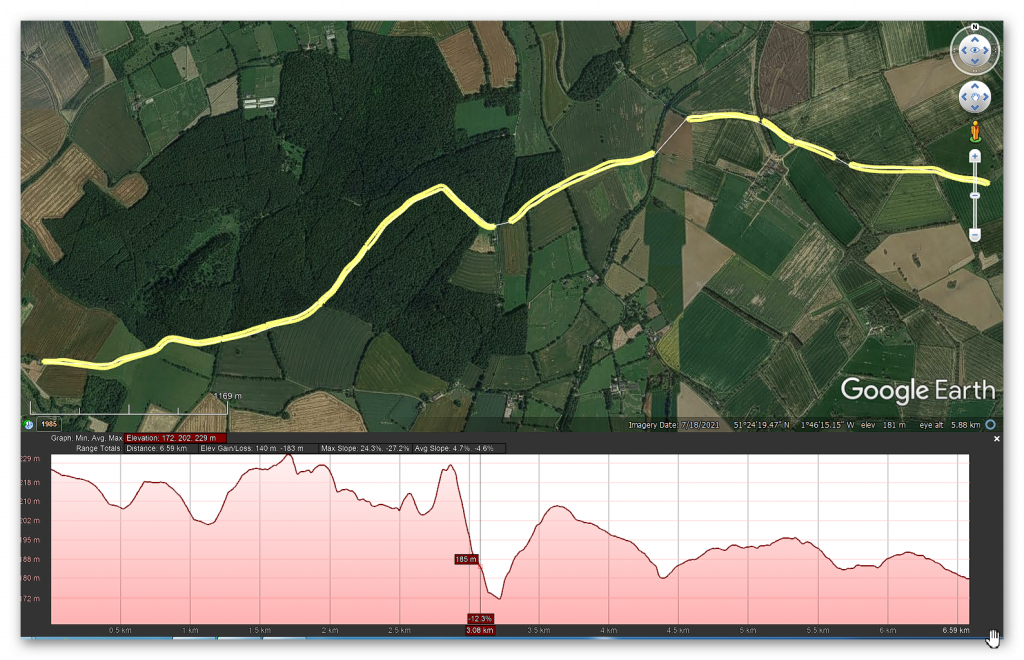

We use an estimated rate of 0.3m per day for calculating sections; on this single section, of the Dyke; we have a total length of 4.3km (4,325m).

At a rate of 0.3m per day over 8 hours – this gives us 12,975 working days. Using 20 person in a work team (with 200 people supporting the workers – to suppy food, water shelter, repair tools and clear the ground in advance of trees and scrubs. This gives us a total of 649 days (1.78 years). The estimate is based on one man cutting 0.3m per day (Ditch down to 2m deep within a chalk bedrock and the piling of the bank).

P.J.Fowler (2001) used 0.1423 metres per hour and claimed 1,000 men built the ENTIRE East Dyke in 30 days working 10-hours a day six days a week??

This ridiculous claim even with modern tools, it would be too demanding, and the logistics of feeding, mending tools and housing 1,000 men were not taken into account.

If we take the East Wansdyke into account – which is a total of 25,408 – we then get a calculation of 84,693 days. That is 11.6 years for the same 200 man tean (20 digging) – which indicates that this Dyke was built in small sections and then joined at a later date?

Twisty Route

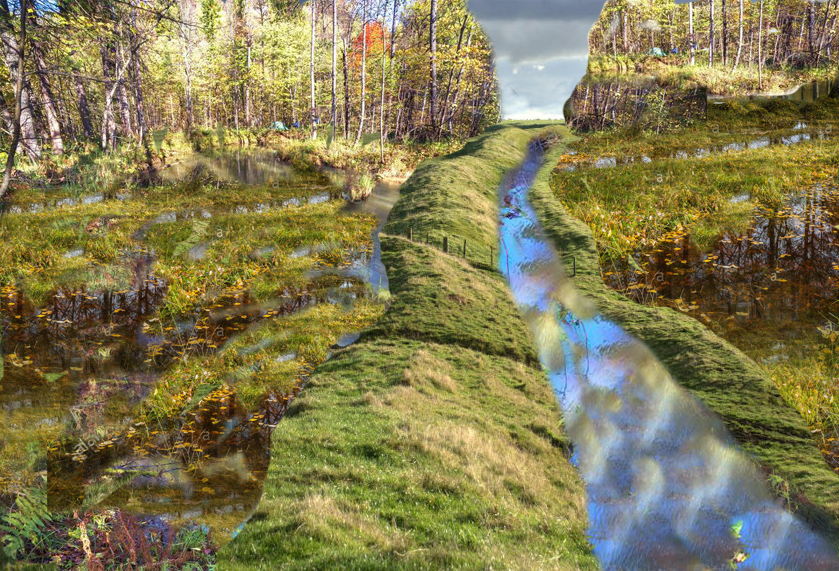

What is clear from the route of this section of Wansdyke is that it is not straight at all; it works against the topology to bend at 90 degrees in some places and dip down unnecessarily into a valley rather than taking the high ground.

But these wild undulations into valleys also cause problems for my hypothesis as a canal. For example, how could a canal move up and down significant gradients without locks?

Well, the answer is that they can’t – but the solution to this problem is in detail, for if you look again at this part of Wansdyke going into an old dry river valley, you see something archaeologists miss – it stops!!

We also saw this from the transition from Section 1 to Section 2 of Wansdyke. The second was a gap, which looked like a piece filled in by farming; there were two other gaps; the first was a later road cutting through and then a railway doing the same.

The Dry River Valley aspect of this part of the canal comes with a massive gradient – if it went to the valley’s bottom, it would make moving a boat very difficult. But we see on LiDAR evidence of the Dyke stopping before reaching the bottom. This is because, at some point in the past, this dry river valley in prehistoric times would not be ‘dry’ but full of water, as shown in the illustration (Fig.49)

This would make sense to the termination on the right as it would initially end at the river’s shoreline. If this was the case, the simple answer to the problem is that at that point, you took the boat across the river, so the gradients of the Dyke in the Mesolithic were small.

But why is there a continuation (bank) of the Dyke down the valley?

This can best be answered by understanding what happened to this earthwork once the waters started to fall in the Neolithic Period.

Logically, as the waters fell, the ditch would have been extended to meet the lower water level until the slope was too extreme to continue and was abandoned. Later once the river had completely dried up (and consequently the rest of the Dyke as the water table would have universally fallen), the natural road (the bank of the Dyke) would be used as a road.

Excavations of similar aspects of Dykes have shown that the bank reduced in height and became flattered like a road and hence more comprehensive. To use this road permanently, the builders adapted the dry river valley element (which would still be boggy for many centuries after the river disappeared) by adding to the bank by removing soil from the ground – but on both sides, making the ditch element smaller and more shallow than the rest of the Dyke and to both sides.

The result of this work looks like a loss of the deep ditch but is more likely a change in its structure – which is seen clearly on parts excavated in other Dykes but impossible to see here without excavation.

Long Barrow

An interesting associated feature can be found just 200m south of Wansdyke Section 2 – A Long Barrow.

“The monument includes a long barrow set above the floor of a dry valley in an area of gently undulating chalk downland. The barrow mound is ovate and orientated east-west. It is 40m long, 27m wide and stands to a maximum height of 3.5m. Flanking the barrow mound to the north and south are ditches from which the material used to form the mound was quarried during the construction of the monument. These survive as earthworks 8m wide and 1m deep” – Historic England

What should be noted is it’s ON THE SHORELINE of the ‘Dry River Valley’ as shown from the suggested water level in our illustration. This is reflected by the ‘track’ (dyke) that connects the shoreline to the main Wansdyke Canal. So are we seeing the Dyke being used at a later date to take the bones of the dead from a reincarnation site to the Long Barrow?

This confirms the river levels at the time of construction and the previously speculated gap in Wansdyke by the river valley top.

Flint Pits

Again, as shown in the previous section (1), another interesting feature near the Dyke is the ‘Old Flint Pits’ as a feature on the 1886 edition of the OS map but not recorded by the Historic Monuments Dept.

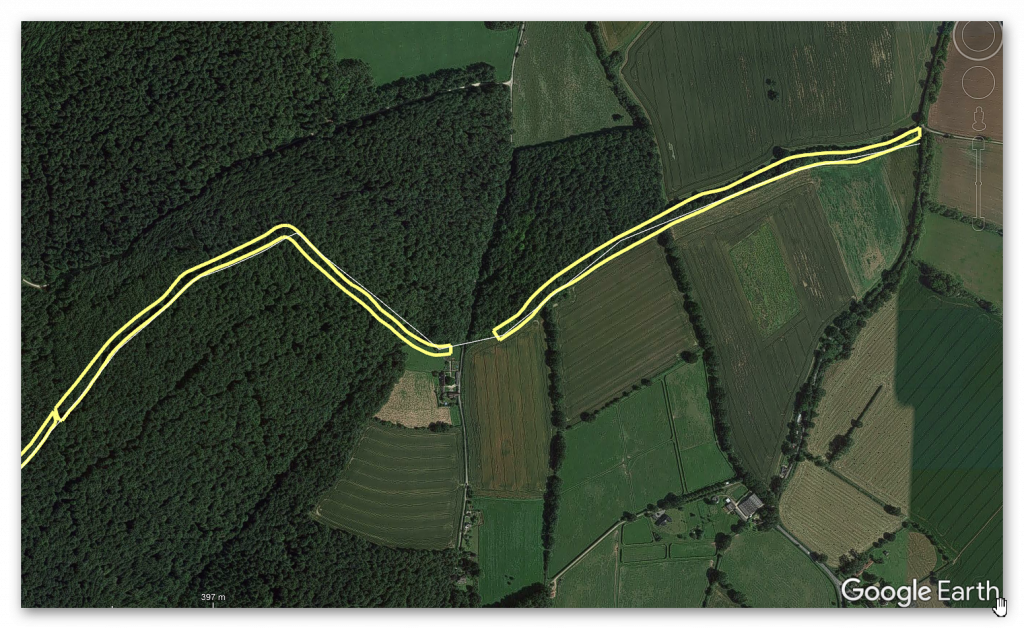

90-degree bend

Another strange and bewildering feature in this section is the 90-degree bend on the Dyke.

This ‘kink’ confirms that Wansdyke was never built as either a Defensive wall or Boundary marker. As if it was a defensive feature, it would not have a ‘gently rounded ditch – it would be square like a castle. If it were just a marker, it would cut across the flat landscape – as it is more work to create such a turning for no reason.

The only logical reason for such an engineering feature is that it was added later when the Water Levels dropped in the Neolithic to follow the landscape topology.

Epilogue

Unveiling the True Purpose of Britain’s Largest Linear Earthworks

The recent publication of three Lidar investigations into Offa’s Dyke, Wansdyke, and The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall has revealed that these structures were built in areas affluent in quarrying and mineral extraction. Archaeologists have overlooked mainly this critical aspect until now.

The likelihood that these earthworks were used to transport materials to rivers for trading is compelling. Moreover, the possibility that they were initially constructed as transport routes for boats during the Mesolithic period, with quarries developing around this infrastructure later, is an intriguing hypothesis that deserves attention.

As we continue to study these ancient linear earthworks with advanced landscape tools like Lidar, we can expect this timeline to become more apparent. What is undeniable is that the old myths of these structures being solely fortifications or boundary markers are complete fiction. While they may have been used as such after their original construction, their primary purpose was much more complex and integral to early trade and transportation networks.

This new understanding challenges long-held beliefs and opens exciting avenues for future research into these remarkable earthworks’ true history and function.

Results from the LiDAR investigations

Wansdyke

With meticulous precision, our investigations have set out to unravel the intricacies enshrouding Wansdyke, delving boldly into the heart of its historical narrative. In so doing, it dares to challenge the archaic views, which have rendered Wansdyke a mere defensive ditch or a boundary marker of the Saxon age. However, a discerning eye reveals that these notions lack the bedrock of objective evidence, for they rely merely on a handful of carbon dates, a commonplace in the annals of sites from that period.

Yet, the gaps within this enigmatic earthwork beckon us to embark on an exploratory journey that hints at the presence of something else entirely – the possibility of water coursing through these river valleys. We dare to propose that these ditches were not mere boundaries but ingeniously designed moated canals, where boats once plied as a means of transport, an ideal mode of travel within a water-rich landscape.

Though our current knowledge may fall short of unearthing all the answers, the profound excavations led by Pitt Rivers present a tantalising glimpse, revealing that water once flowed through these ditches. And the Romans themselves, much later, saw fit to repurpose these canals, affirming their practicality and utility in the annals of history.

The advent of LiDAR has unfurled before us an unprecedented vista, affording a sweeping survey of over 1500 Scheduled Dykes throughout Britain. In the luminous wake of this technology, a compelling story unfolds, hinting at Wansdyke’s Mesolithic origins, challenging established beliefs, and unveiling its construction during a period of abundant river levels, a time far more distant than previously perceived.

With their customary flair for adaptation, the Romans likely reworked sections of Wansdyke, leaving behind a more cohesive structure than its counterparts. The Vallum by Hadrian’s Wall and Offa’s Dyke bear the indelible marks of their prehistoric origins, standing as testaments to the Romans’ quarrying and stone-delivery endeavours.

Yet, we venture further into the mists of history, exploring prehistoric mining, the significance of quarried materials, and their vital role in facilitating trade – not just within Britain’s borders but beyond, crisscrossing the conflation of Europe. This revelation dispels earlier scepticism and shines a light on the sophisticated network of international trade that flowed with the currents of time, enriching Wansdyke’s profound legacy as a conduit of a vibrant and interconnected ancient civilisation.

The veil of uncertainty still shrouds the origins of West Wansdyke in a cloak of ambiguity. While the passage of time has not yet delivered a definitive date, the prevailing narrative, tethered to a carbon dating of 1500 BCE, finds itself juxtaposed against emerging evidence. This evidence, born of meticulous inquiry, casts shadows of doubt upon the established chronology and beckons us to reevaluate our understanding.

In the chronicles of academia, where scepticism is both a guardian of rigour and a hurdle to innovation, the seeds of inquiry were sown some fifteen years ago. The publication that dared to challenge convention and present a different perspective on West Wansdyke stirred a tempest within the academic community. Accusations of ‘pseudoscience’ echoed like distant thunder, casting a shadow over the revelations that dared to dissent.

Yet, the march of progress is often fueled by the fervour of inquiry and the evolution of knowledge. Archaeologists, driven by a relentless pursuit of truth, have not shied away from the fray. In an embrace of scientific discovery, new dating evidence has emerged—a beacon of revelation that punctures the shroud of scepticism that once enshrouded the discourse.

Carbon dating, that time-traveller’s tool that peers into the past through the lens of isotopes, has yielded results that lend credence to the suspicions germinating in the fertile soil of curiosity. LiDAR, with its laser-guided gaze, has unveiled hidden landscapes and confirmed the prehistoric existence of canals—ancient pathways etched into the earth by the hands of civilisations long past.

As we stand at this juncture, it is not merely the story of West Wansdyke that unfolds before us; it is a testament to the evolution of thought and the malleability of understanding. The ‘pseudoscience’ that once raised eyebrows now stands vindicated—a reminder that the boundaries of knowledge are ever-shifting, ever-expanding, yielding to the tenacity of those who dare to question.

In the grand theatre of history, where narratives are woven from threads of evidence and conjecture, the tale of West Wansdyke takes centre stage. It serves as a reminder that even the most firmly established edifices of understanding can be reshaped by the currents of new insight. The academic stir that was ignited by dissenting revelations has matured into a symphony of acceptance—a harmonious acknowledgement that the pursuit of knowledge, however tumultuous, is the essence of scholarly endeavour.

As we navigate the twists and turns of this historical journey, we honour the legacy of those who dared to defy convention, the archaeologists who continued to dig beneath the surface, and the spirit of inquiry that animates the quest for truth. In this narrative, West Wansdyke emerges not just as a physical structure of the past, but as a symbol of the human spirit’s unyielding march toward comprehension—a testament that even in the face of scepticism, the pursuit of understanding remains an unwavering beacon of progress.

Consequently, in the HE publication ‘Prehistoric Linear Boundary Earthworks: Introductions to Heritage Assets. Swindon. Historic England 2018’.

The archaeologists confess that “Some of the earliest (Dykes) seem to date to the later Neolithic period: on Ebberston Common, the latest sequence of at least six pit alignments appears to predate the construction of a round barrow which would typically date to the earlier Bronze Age, around 2000 BC. “(see Page Fig.87. Page 151 for full quotation).

And as a consequence of their endeavours now are happy to plush a timeline of Dyke construction, vindicating my original work and allowing us to date West Wansdyke from my research on water levels in the prehistoric from the middle Mesolithic to the Bronze Age.

Hadrian’s Wall – The Vallum

Our Findings

Before we reflect on our findings Section by Section, It may be beneficial to look at the total statistics for some aspects of Hadrian’s Wall, as such details have not been found in our research on this subject.

Vallum

Total length found: 73,812m (45.86 miles) – 62% of the entire wall length

Total length missing: 40,075m (24.90 miles) – 35% of the Vallum length

The total length of Vellum 113,887m (70.77 miles)

In comparison, Hadrian’s Wall is reported as 80 Roman miles or 73 standard miles in length.

Within the 70.77 miles of the Vallum, we have identified – within 200m of the construction:

46 Springs (as specified by the 1800 OS maps series)

54 Quarries

14 Prehistoric Ancient sites

To judge if the frequency of these objects are standard or an anomaly of the Vallum – we have measured two roughly parallel lines to the Vallum, one 5 miles to the north and the other to the south, so still conforming to a similar environment and then counted the frequency of these objects that are also within 200m of the experimental map lines:

Northern Test line

12 Springs

25 Quarries

1 Ancient site

Southern Test Line

10 Springs

30 Quarries

3 Ancient Sites

Consequently, we can now judge the Vallum path against our map test lines:

10 v 46 Springs – Vallum has 460% more Springs

30 v 54 Quarries – Vallum has 180% more Quarries

14 v 2 Ancient Sites – Vallum has 700% more sites

With these fantastic statistics in mind, we can now take a detailed look at the LiDAR investigations, starting with Section A, where we find that the Vallum ends some distance before the end of the Wall on the Bowness-on-Solway coast.

This terminus seems to be at a point of a Paleochannel/Dyke that turns and heads south overland, which has no connection to the Wall. This Section shows that the Wall was built at an inappropriate distance from the current river to be defensive – as attackers would be free to land and muster.

The LiDAR map shows the likelihood that the river was higher in the Roman period and that the Wall was built on its shoreline, making it a much more secure feature. This raised water level would suggest that the Paleochannel was full of water and was used to link into the Vallum as a canal feature.

Section B, shows that the Vallum was in this area (sections A & B) as short-run (2.6 miles) and not continuous. The terminal point to the east of this run again is in a river valley, which was again higher than today at the time of Roman occupation, allowing boats to enter and exit from the river Esk to supply or deliver Stone to the Wall as there is an absence of the suggested ‘Military Way’ that was supposed to be constructed for this purpose.

We will not see any signs of the Military Way (see case study) for the next 24.2km, indicating that the Vallum was the primary source of supply and communication.

Section C, demonstrates that the Vallum disappears for 2.6 miles on the LiDAR map. No excavation evidence shows it was below the surface; we can only conclude that it did not exist in this Section. This questions the old theory about the Vallum being constructed as a defence structure either before the Wall was built or after to defend the south flank – as attackers could just walk around it?

This Section also offers further support to the higher water table at the time of the Wall’s construction as it seems to bend around the shorelines of these higher river levels, which otherwise make no engineering or defensive sense?

Sections D and E, illustrate the raised water levels of prehistory and, consequently, the path of the Wall and Vallum, which in places (such as in the River Eden) disappears, indicating that the Vallum was probably constructed on an existing ‘Dyke’ and enlarged for their purposes?

Sections F, G and H show the first signs of the Roman Road called Stanegate (see case study). The Vallum again is broken in its course by the river valleys in this area, eradicating any evidence of its existence. It also shows that the Vallum headed towards river valleys rather than avoiding them, which again would suggest these were earlier prehistoric features that were reused.

Vallum – was once a series of prehistoric dykes which were recut and extended to deliver supplies and stone to the Wall.

Stanegate – does not exist as a road but has a river connection to the first five sites.

Military Way – Does not exist as an independent road(way) but is observable in areas not covered by the Vallum.

The Antonine Wall – was once a series of Dykes that was reconnect together and recut.

Offa’s Dyke

The Total length of Offa’s Dyke (including gaps and missing sections) 279,745m (173.8 miles)

Total length Found (by LiDAR): 95,044m (59.2 miles) – 34% of the entire length

Total length Missing (by LiDAR): 185,476m (114.6 miles) – 66% of the entire length

Total number of Gaps in the Offa’s Dyke – 70

Total number of Scheduled Monuments in Listing: 237

Features

Within the 59.2 miles of Offa’s Dyke, we have identified – within 200m of the construction:

118 (33 Natural Springs)/Wells/Ponds (as specified by the 1800 OS maps series – Wells and Ponds included to show high water table)

303 Quarries/Bell Pits (Bell Pits Ancient Quarry Holes) ave of 5 Quarries per mile of Dyke

12 Prehistoric Ancient Sites

4 Barrows

7 Roman Sites

52% of Sections are linked to each other

20% of Sections are connected to existing rivers

28% of Sections join Paleochannels

Summary

Section A – Total 20,201m. 14 Gaps – 6,758m missing (34%)

Section B – Total 110,545m. 10 Gaps – 106,768 missing (97%)

Section C – Total 55,905m. 17 Gaps – 7,990 missing (14%)

Section D – Total 56,369m. 22 Gaps – 29,848 missing (53%)

Section E – Total 36,725m. 7 Gaps – 33,101 missing (90%)

Our findings concluded that these landscape features are much more exciting and complex than the archaeologists currently imagine, as each Section has its interest that finally gives us a solution to the construction and functionality of the Dyke.

Section A – Runs around the hills surrounding Chepstow and the River Wye. This Dyke is no boundary or marker as the river would be a better solution to both causes. But what it does show is the connection to Quarries and Roman Roads that would have probably linked to the canal system it inherited from the ancient Dyke builders. These ‘linear earthworks’ were created to assist in trade during both prehistory and later Roman era until the canals dried up when the roads built upon the banks of these Dykes replaced the method of transport.

Section B – Shows why the Dyke is not interconnected, as 97% of it is missing, and there is not functionality or design that links together the small portions of Dyke that is in this Section.

Section C – Has the least missing sections, yet it still has 14% missing with 17 gaps, indicating that these Dykes are a series of individual trading canals and not a single entity. This trading can be seen in the extensive quarries in this area, which have been mined for their mineral wealth for thousands of years.

Each hill has a different design from the last regarding width and Depth of the Ditch. What we are seeing is a degree of uniformity in access to quarries and water sources, and natural springs along the Dyke.

Section D – This is a 50/50 series of Dyke to gap ratio, again showing that it is connected to Quarries and Mining, particularly Coal Mining, which the Romans widely used. These are some of the largest coal mines in Britain. The Dyke does not just come close – it in some cases the alignment goes through the middle of these quarries, with on average four quarries per Section which makes any suggestion that these Dykes were not used in conjunction with the minerals being extracted (as we see also in The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall) and were constructed for another purpose as completely absurd.

Section E – Even archaeologists (including Fox) now admit that this is a different series of Dykes (Whitford Dyke) and not part of Offa’s Dyke as it’s too dysfunctional.

So, our conclusion about Offa’s Dyke is that we are looking at a series of working Dykes – initially built in prehistoric times and then utilised (as again we found in The Vallum) by the Romans to service the same Quarries for trading purposes.

In particular, we see this Roman influence in Section D as these are Coal minerals, which we know they used to heat the hypocaust underfloor furnaces of their Bath and home houses which to date Archaeologists have failed to investigate the sources of this coal and how it was transported.

This was an extracts from the NEW Book Ancient Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke available on Amazon as a FULL COLOUR HARD BACK (£19.95) or a ECONOMY (£4.99) SOFTBACK black and white VERSION – it is also available as a KINDLE (£1.99) book. For further information about our work on Prehistoric Britain visit our WEBSITE or VIDEO CHANNEL.

Book details

- ASIN : B0BF31GQKC

- Publisher : Independently published (18 Sept. 2022)

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 134 pages

- ISBN-13 : 979-8353488897

- Dimensions : 15.24 x 1.3 x 22.86 cm

- Illustrations: 85

- Customer reviews: 5.0 out of 5 stars 1 rating

For more information about British Prehistory and other articles/books, go to our BLOG WEBSITE for daily updates or our VIDEO CHANNEL for interactive media and documentaries. The TRILOGY of books that ‘changed history’ can be found with chapter extracts at DAWN OF THE LOST CIVILISATION, THE STONEHENGE ENIGMA and THE POST-GLACIAL FLOODING HYPOTHESIS. Other associated books are also available such as 13 THINGS THAT DON’T MAKE SENSE IN HISTORY and other ‘short’ budget priced books can be found on our AUTHOR SITE or on our PRESS RELEASE PAGE. For active discussion on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that is published on our WEBSITE you can join our FACEBOOK GROUP.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?