Cissbury Ring through time

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Cissbury Ring – Summary

- 3 Flint Mines, Radiocarbon Dates, and Archaeological Insights

- 3.0.1 The Beginnings of Flint Mining

- 3.0.2 Excavation History

- 3.0.3 Structure of the Flint Mines

- 3.0.4 Radiocarbon Dating Evidence

- 3.0.5 Artifacts and Findings

- 3.0.6 The Iron Age Transformation

- 3.0.7 Lynchets and the Dyke Debate

- 3.0.8 Pits and Deposit Sites

- 3.0.9 The Saxon Mint Hypothesis

- 3.0.10 Folklore and Myths

- 3.0.11 A Concluding Perspective

- 3.0.12 Post-Glacial Flooding

- 4 Further Reading

- 5 More Blogs

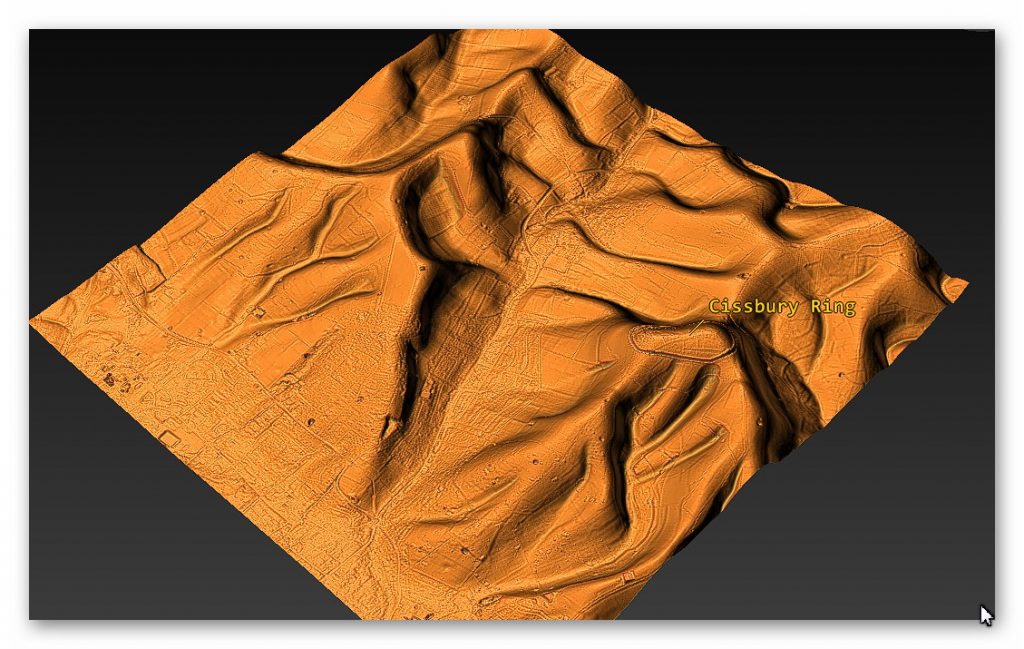

Introduction

This is a journey through time looking at the prehistoric site of CISSBURY RING and its surrounding Landscape based on the new third (2020) edition book of the best seller – that contains conclusive and extended evidence of Robert John Langdon’s hypothesis, that rivers of the past were higher than today – which changes the history of not only Britain, but the world. In his first book of the trilogy ‘The Post-Glacial Hypothesis’, Langdon discovered that Britain was flooded directly after the last Ice Age, which remained waterlogged in to the Holocene period through raised river levels, not only in Britain, but worldwide.

Cissbury Ring – Summary

Traditionally classified as an Iron Age hill fort, is actually one of the oldest and largest Neolithic flint mining sites in Britain, covering an impressive 65 acres. It ranks second only to Maiden Castle in terms of size. However, its primary historical significance lies not in its defensive role, but in its function as a major center for flint extraction and trade. This site represents one of the earliest known industrial landscapes in prehistoric Britain, with mining activity that dates back to around 4000 BCE, challenging the conventional Iron Age classification.

The site contains approximately 200 flint shafts, some extending as deep as 12 meters, and mining activities here spanned an extraordinary 900-year period. These shafts were dug into the chalk bedrock to access high-quality flint, a critical resource in the Neolithic era for tool-making and other practical purposes. Flint extraction at Cissbury was a meticulous process, involving the excavation of large shafts and tunnels to reach the valuable deposits. Skilled miners likely used bone and stone tools to carve through the chalk, carefully extracting flint nodules that would have been in high demand across Britain and beyond.

The surrounding landscape is marked by a series of interconnected ditches and dykes that connect ancient paleochannels to the site’s main ditch, forming an intricate transportation network. This system likely facilitated the movement of flint from the mines to boats for trade, indicating Cissbury’s role as a strategic trading hub. These channels would have allowed the extracted flint to be efficiently transported to nearby waterways, where it could be shipped to other regions.

The sheer scale and complexity of the mining operations at Cissbury Ring provide a glimpse into the sophisticated logistical organization of Neolithic communities. This site was not merely a fortified settlement, but a bustling center of industry, resource management, and trade in prehistoric Britain.

Flint Mines, Radiocarbon Dates, and Archaeological Insights

Cissbury Ring in West Sussex, one of Britain’s largest hillforts, is a window into ancient Britain, encompassing Neolithic, Iron Age, and Romano-British activities. Covering 60 acres, this site has yielded an extensive collection of evidence that informs us about early mining practices and settlement patterns. The flint mines here date back to around 4000 BC and have provided valuable insights into Neolithic industrial activity and ritual practices.

The Beginnings of Flint Mining

The flint mines at Cissbury, dating to the Neolithic period, span over 9 hectares, with more than 270 shafts identified in surveys. These shafts, measuring between 3 and 36 meters in diameter, formed a crescent shape across the hillside. Flint extraction here was extensive, as Cissbury was a vital source of high-quality flint, essential for tool-making in ancient Britain. Miners used red deer antlers and shoulder blades as tools, effectively chiseling through layers of chalk to reach seams of flint.

Excavation History

Early excavations at Cissbury began in the 1850s with George Irving, who initially misinterpreted the shafts as water reservoirs. In the 1860s, A.H. Lane-Fox correctly identified the pits as Neolithic flint mines, providing a more accurate interpretation of the site. Excavations continued with John Pull in the 1950s, although his findings were not fully published. Nevertheless, Pull’s work was pivotal in expanding our understanding of flint mining techniques used at Cissbury.

Structure of the Flint Mines

The shafts at Cissbury led to a complex network of underground galleries, which were typically 3 feet high and supported by chalk pillars. The miners worked in hazardous conditions, as evidenced by skeletons found within collapsed galleries. The shafts were often backfilled with chalk rubble after extraction. Galleries interconnected the shafts, allowing for multiple points of access and exit. Excavators found evidence of flint knapping on-site, as well as animal bones and other artifacts, suggesting that the pits might have had secondary uses.

Radiocarbon Dating Evidence

Radiocarbon dating of antler picks from the site provided dates of 4720±150 BP, 4650±150 BP, and 4730±150 BP, which correspond to 3900-3030 BCE and 3780-2920 BCE. These dates confirm that the flint mines were in use during the Neolithic period, solidifying Cissbury’s importance as a prehistoric mining center. The discovery of animal bones, including ox, pig, and wild boar, within these pits indicates that miners were using the site not only for extraction but possibly for ritualistic purposes as well.

Artifacts and Findings

The tools used at Cissbury were mainly made from red deer antlers, adapted for use as picks and shovels. Excavators found other unique items, including miniature flint axes and chalk carvings, with one shaft containing a woman’s skeleton buried feet-first, accompanied by bones of various animals. This implies a possible ritualistic burial, as several of these pits contained remains in arrangements suggesting ceremonial depositions.

The Iron Age Transformation

In the Iron Age, around 700 BC, fortifications were constructed around the site, enclosing approximately 24 hectares. These defenses consisted of ramparts and ditches, forming a formidable barrier. Excavations revealed Romano-British pottery and oyster shells, indicating continued occupation and use for agriculture and defense. The hillfort was later fortified during WWII, and the site has undergone minimal modern excavation due to its status as a scheduled ancient monument.

Lynchets and the Dyke Debate

A particularly intriguing aspect of Cissbury is the lynchets, terraced formations traditionally associated with ancient agriculture. However, some propose that these features might actually be misidentified dykes, suggesting ancient water levels. While dykes usually include raised embankments and drainage systems, the lynchets at Cissbury lack these structural elements. Moreover, the area’s chalk soil would make long-term water retention impractical, raising doubts about the water-management hypothesis.

Pits and Deposit Sites

Archaeologists speculate another layer to Cissbury’s history as pits for ritual deposition. One of the fascinating discoveries is a pit containing an assortment of artefacts, including chalk loom weights, an iron knife, and sling stones. These objects hint at ceremonial uses, possibly related to agricultural or religious practices. The pit aligns with similar features at Mount Caburn, suggesting ritual depositions were a shared practice among nearby communities. Sadly, the reality is this is an industrial site for processing minerals, and so this is just ‘industrial waste’ at best.

The Saxon Mint Hypothesis

Cissbury might have housed a Saxon mint, as coins from Ethelred II and Cnut bearing mint marks have been linked to the area. Although no direct archaeological evidence supports this claim, the suggestion adds another layer of historical intrigue to the site. Such mints were typically moved to fortifications during times of conflict, underscoring the strategic significance of Cissbury in the early medieval period. The better solution is that more than flint can be found in the mines – sadly, archaeology does not possess the techniques or experience to look for such minerals, as they do not excavate quarries.

Folklore and Myths

Local legends attribute Cissbury’s construction to the Devil, who allegedly flung earth around the Downs, creating the hillforts. Other stories speak of treasure guarded by serpents and even UFO sightings, adding a sense of mystery and complete nonsense to the site. There are also tales of fairies dancing at Cissbury, blending folklore with historical intrigue and showing how the site has captured imaginations for centuries.

A Concluding Perspective

Cissbury Ring remains an essential site for understanding ancient Britai,n, with its flint mines, Iron Age ramparts, and complex web of myths. While the theory of lynchets as dykes is interesting, it is unlikely given the physical characteristics of these features. Archaeological evidence supports the interpretation of lynchets as agricultural, with no clear indicators of water-management systems in place. Yet, Cissbury’s diverse history, from flint mining to potential Saxon minting, reflects a multifaceted legacy that continues to inspire research and speculation.

In conclusion, Cissbury Ring is more than a hillfort—it is a testament to the ingenuity, resilience, and cultural depth of ancient peoples. The site’s layers of history provide a tangible link to the past, offering insights that span millennia and spark continued interest in Britain’s ancient heritage.

Post-Glacial Flooding

In this second book of the series ‘The Stonehenge Enigma’, he also shows that a new civilisation known to archaeologists as the ‘megalithic builders’ adapted to this landscape, to build sites like Stonehenge, Avebury, Woodhenge and Old Sarum, where carbon dating has now shown that these sites were constructed about five thousand years earlier than previously believed. Within the trilogy ‘Prehistoric Britain’, Langdon looks at the anthropology, archaeology and landscape of Britain and the attributes and engineering skills of the builders of these megalithic structures. (Cissbury Ring through time)

Including finding and dating the original bluestones of Stonehenge Phase I from the quarry of Craig-Rhos-Y-Felin in Wales, five thousand year earlier than current archaeological theory and how this civilisation used the sites surrounding Stonehenge at a time of these raised river levels. This unique insight into how the prehistoric world looked in the ‘Mesolithic Period’ allows Langdon to explain archaeological mysteries that have confused archaeologist since the beginning of the science and allows us to make sense of these sites, allowing us to understand their function for this society for the first time. (Cissbury Ring through time).

With over thirty ‘proofs’ of his hypothesis and one hundred and twenty-five peer-reviewed references – Langdon uses existing excavation findings and carbon dating to forward a new understanding of the environment and our ancient society, which consequently rewrites our history books and allows us to find more conclusive and persuasive evidence which is currently trapped in our landscape, ready to be discovered by future students of archaeology. Articles on this Trilogy and an Active FaceBook Group where you can leave comments and get feedback can be found at:

Articles: https://prehistoric-britain.co.uk/

FaceBook Group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/prehistoricbritain

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Unlocking the Mysteries of British Prehistory

Delve into the depths of time, as we embark on a captivating voyage into the enigmatic world of British prehistory. www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk is your portal to a treasure trove of archaeological wonders, modern LiDAR reports, and fascinating insights from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy. This immersive digital hub is your key to unlocking the secrets of Britain’s ancient past.

A Glimpse into the Robert John Langdon Trilogy

Step into the shoes of Robert John Langdon, a dedicated explorer of Britain’s prehistoric mysteries. His trilogy, comprising “The Stonehenge Enigma,” “Dawn of the Lost Civilization,” and “The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis,” is a literary marvel that unravels the untold tales of our ancestors. These books take you on an exhilarating journey through time, meticulously researched and backed by over 125 references from esteemed scientists, archaeological experts, and geological researchers.

Dive into the World of LiDAR

At www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, we harness the power of LiDAR technology to unearth hidden landscapes and archaeological marvels. Our LiDAR reports offer a modern lens through which you can peer into ancient history. Explore the effects of flooding on the British environment after the great ice age melt, a phenomenon that has shaped the landscape we see today. Join us in decoding the mysteries of our past using cutting-edge technology.

A Multimedia Experience

Our commitment to storytelling extends beyond the written word. Robert John Langdon has curated a rich multimedia experience, including a YouTube web channel featuring over 100 investigations and video documentaries. These visual journeys complement his classic trilogy, providing a multi-dimensional understanding of prehistoric Britain. From Stonehenge’s construction in 8300 BCE to the lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire known as ‘Silbury Avenue,’ these documentaries offer an immersive experience that brings history to life.

Explore the ’13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in Ancient History’

History is replete with anomalies and enigmas that defy explanation. Robert John Langdon has curated a collection of such historical curiosities in ’13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History.’ These peculiar occurrences and unanswered questions will leave you pondering the mysteries of the past, inviting you to join the debate on their possible interpretations.

Cissbury Ring through time

More Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: 2024 Blog Post Review - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Statonbury Camp near Bath - an example of West Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Antonine Wall - Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Mesolithic Stonehenge - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Case Study - River Avon - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Extreme Weather & Ancient Subterranean Shelters - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Antler Pick Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Rivers of the Past were Higher – an Idiot’s Guide - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: From the Rhône to Wansdyke: The Case for a Standardised Canal Boat in Prehistoric Britain - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Dyke Construction - Hydrology 101 - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Silbury Avenue - Avebury's First Stone Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon's Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists? - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain's First Monument - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Farming Migration Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Wansdyke Flipbook - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Subtropical Britain Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Prehistoric Canals - Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Problem with Hadrian's Vallum - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Solved - Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Caerfai Promontory Fort - Archaeological Nonsense - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: First Hillforts, Then Mottes — Now Roman Forts? A Century of Misidentification - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Britain's First Road - Stonehenge Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge - Prehistoric Britain