The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Logistical Impossibility of Fortress Hillforts

- 3 Danebury – Case Study

- 4 Maiden Castle – Case Study

- 5 Maiden Castle and the Myth of the Massacre

- 6 The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- 6.0.1 Introduction

- 6.0.2 The Scale of Maiden Castle

- 6.0.3 Estimating Defence Manpower

- 6.0.4 Logistical Support Requirements

- 6.0.5 Water Supply Challenges

- 6.0.6 The Missing Wells

- 6.0.7 Livestock and Food Production

- 6.0.8 Manufacturing Weapons and Armour

- 6.0.9 Lack of Residential Structures

- 6.0.10 The Problem of Evidence

- 6.0.11 Alternative Theories

- 6.0.12 Conclusion

- 6.0.13 Final Thoughts

- 7 Old Sarum – Case Study

- 8 Comparison Chart

- 9 Conclusion

- 10 Further Reading

- 11 Other Blogs

Introduction

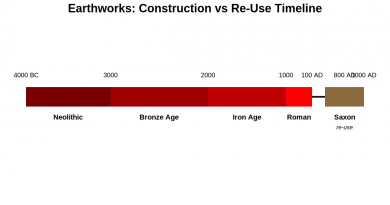

While some hillforts may have been adapted for defence during later periods — particularly during Roman expansion — the majority were not originally constructed as military installations. Instead, they served multifunctional roles in prehistoric societies: economic, ceremonial, territorial, and social.

In the wake of Hawkes’ renowned treatise ‘Hillforts’ (Hawkes 1931), scholars of archaeology undertook the arduous task of categorising hillforts, drawing upon the limited evidence at their disposal. Primarily, these divisions hinged on considerations of size, location, the construction of ramparts, and chronological context. In a relatively recent endeavour the author Cunliffe, put forth a scheme tailored to the Wessex region (Cunliffe 1984b), which delineated certain overarching classifications for these forts (The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax):

Early hilltop enclosures, typically encompassing over 10 hectares of terrain.

Small, strategically fortified settlements, perched prominently, often occupying areas ranging from 1 to 3 hectares.

Early hillforts, characterised by univallate contour works, typically spanning 3 to 7 hectares.

Developed hillforts, generally falling within the 3 to the 7-hectare range but frequently boasting multivallate defences.

The quintessential definition for this prehistoric phenomenon reads as follows: A hillfort constitutes a form of earthwork employed as a fortified sanctuary or defended habitation, strategically positioned to exploit elevated terrain for defensive advantage.

This classification endured unchallenged for more than seven decades – they are now, according to the repository of knowledge that is Wikipedia, primarily of European origin, belonging to either the Bronze Age or Iron Age, with some even extending into the post-Roman era. The fortifications typically trace the natural contours of a hill, comprising one or more tiers of earthworks, fortified by stockades or defensive walls and flanked by external ditches.

Celtic hill forts came into their own during the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age, aligning roughly with the inception of the first millennium BC. They continued to proliferate across various Celtic regions of central and western Europe until the advent of the Roman conquest. Their prevalence was most pronounced during the later epochs, including the Urnfield culture and Atlantic Bronze Age (circa 1300 BC – 750 BC), the Hallstatt culture (circa 1200 BC – 500 BC), and the La Tène culture (circa 600 BC – 50 AD).

This transformation in our comprehension of hillforts owes a substantial debt to the extensive work undertaken by Barry Cunliffe at Danebury during the 1970s.

Prehistoric Europe witnessed a burgeoning population. Estimates suggest that around 5000 BC, during the Neolithic era, the population of Europe fluctuated between 2 million and 5 million. In the Late Iron Age, this number swelled to an estimated 15 to 30 million. With the exception of Greece and Italy, which were more densely populated, the overwhelming majority of settlements during the Iron Age were relatively diminutive, housing no more than 50 inhabitants. Hillforts, however, stood as an exception, accommodating as many as 1,000 individuals.

With the advent of oppida in the Late Iron Age, settlements expanded to house populations as substantial as 10,000. As the populace swelled, so too did the intricacy of prehistoric societies. Around 1100 BC, hillforts emerged and over the ensuing centuries proliferated throughout Europe. They served a diverse array of functions, functioning variously as tribal hubs, fortified bastions, focal points of ritualistic activities, and centres of production.

The Logistical Impossibility of Fortress Hillforts

A closer examination of hillfort distribution across Britain and Ireland raises serious doubts about the traditional interpretation of these sites as purely defensive structures.

- There are over 3,300 hillforts spread across the British Isles.

- Distribution is heavily clustered, not evenly spaced — with extreme examples like the Isle of Man, where 32 enclosures exist in just 572 square kilometres (one hillfort every 5–6 km²).

- 30% of all known hillforts are located on the coastline, and an estimated 50% more are situated along prehistoric river systems — meaning up to 80% had direct waterborne access.

- Around 70% of hillforts are associated with quarrying, mining, or resource extraction zones.

If each hillfort was purely a refuge or defensive fort:

- There would need to be thousands of separate, fortified populations,

- Thousands of armies ready to defend them,

- And consistent evidence of sustained regional warfare.

Yet the archaeology shows otherwise:

- Few hillforts have evidence of prolonged occupation.

- Evidence of mass conflict is rare and localised.

- Many sites lack obvious military architecture (such as palisade trenches or true gatehouses).

The only logical explanation is that hillforts were primarily multifunctional hubs — sites of seasonal gathering, trade, ceremony, and political negotiation, with defensive adaptations made only when necessary.

So, what shall we make of this revelation?

Is it indeed, apt to continue branding them as exclusively Iron Age enclaves? Of course, there are vestiges from the Iron Age to be found within these enclosures, but they also harbour traces of the Middle Ages, Roman artefacts, and, most tellingly, flint relics dating back to the Neolithic/Mesolithic era.

To delve into the heart of this matter, let us focus our attention on the paramount example of an Iron Age fort in Britain – Danebury in Hampshire, and its peer, the grandiose Maiden Castle in Dorset. Together, we shall sift through their findings, unearthing the curious conundrum of archaeological classifications.

Danebury – Case Study

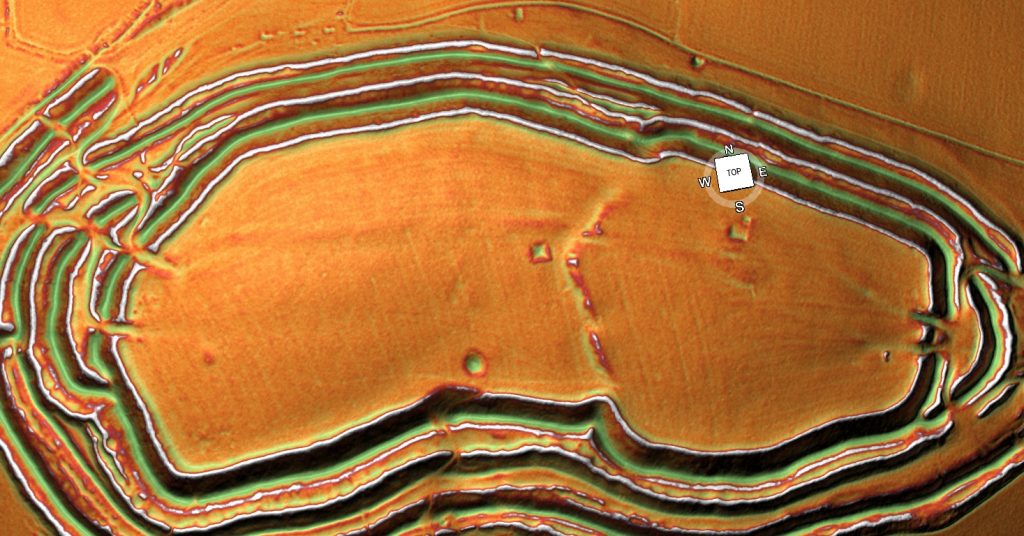

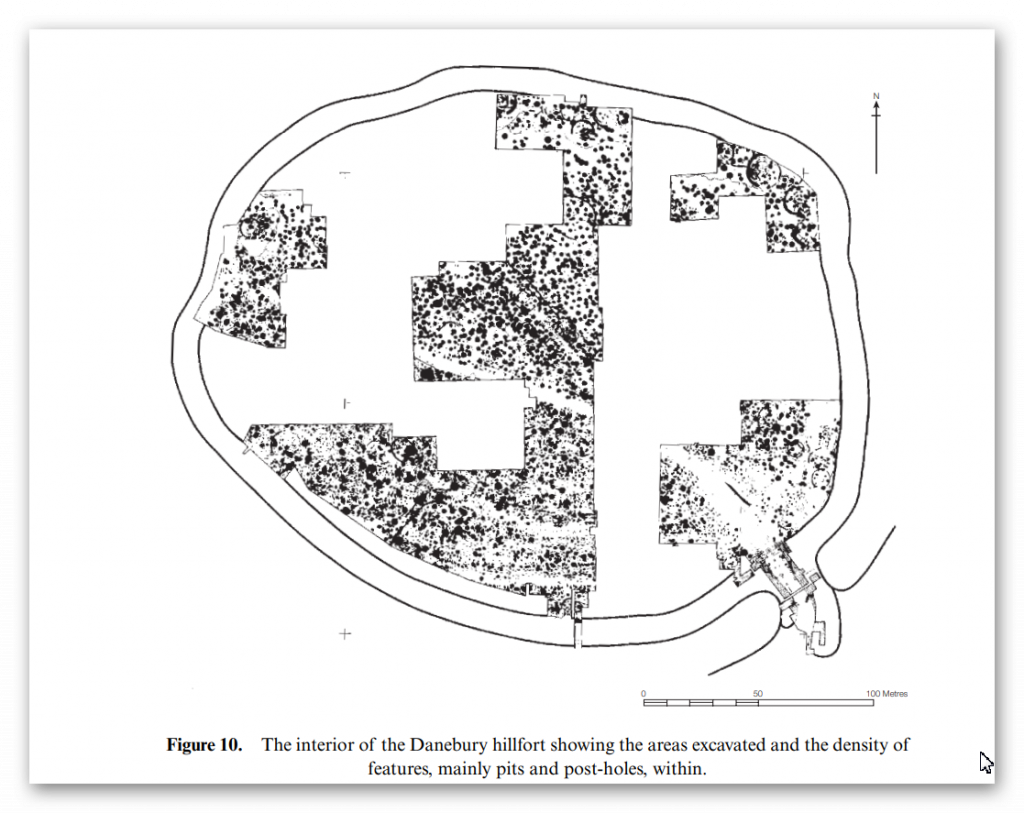

According to Wikipedia: Danebury is an Iron Age hillfort in Hampshire, England, about 19 kilometres (12 mi) north-west of Winchester (grid reference SU323376). The site, covering 5 hectares (12 acres), was excavated by Barry Cunliffe in the 1970s. Danebury is considered a type-site for hill forts, and was important in developing the understanding of hillforts, as very few others have been so intensively excavated.

Built in the 6th century BC, the fort was used for almost 500 years, during a period when the number of hill forts in Wessex greatly increased. Danebury was remodelled several times, making it more complex and resulting in it becoming a “developed” hill fort. It is a Scheduled Monument and a Local Nature Reserve called Danebury Hillfort. The Scheduled Monument is surrounded by a Site of Special Scientific Interest, designated as Danebury Hill.

Looks pretty straightforward and comprehensive – so what is wrong?

In the annals of Iron Age Britain, a conspicuous absence of historical records compels us to rely solely on the tools of archaeology to reconstruct the rich tapestry of events at sites like Danebury and other ancient forts. Crafting a comprehensive and authoritative historical narrative from a single site becomes a feat of no small magnitude. Typically, in the realm of science, hypotheses are formulated and subjected to rigorous testing and fine-tuning by fellow scientists. But in this case, a unique anomaly emerges.

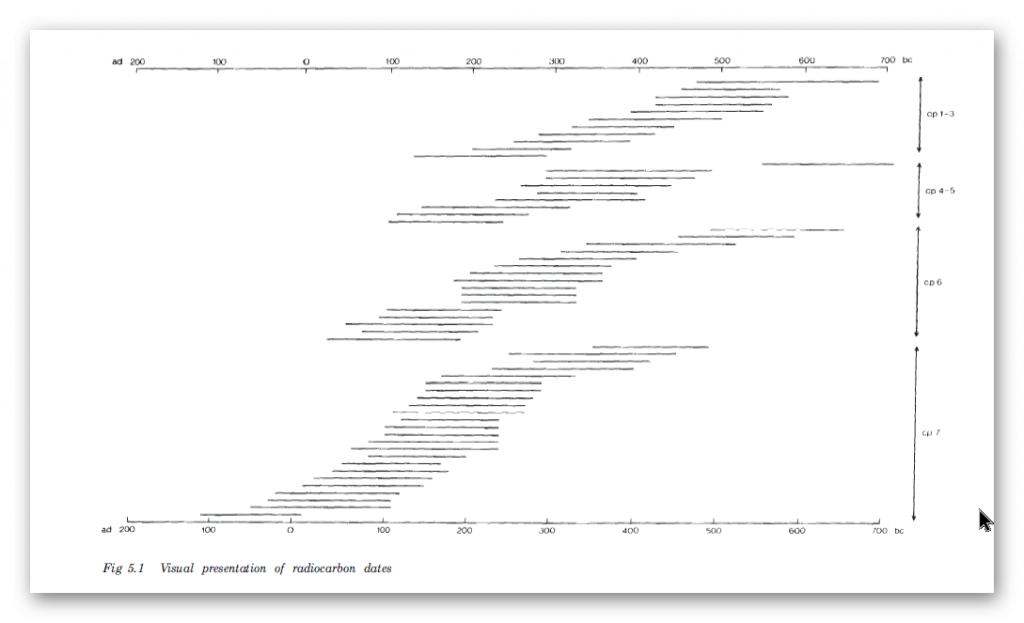

It is worth noting that the established dates pertain solely to the interior pits of the site. These dates offer insight into the latest period of habitation, for obvious reasons, or at best, the principal period of occupancy, but they do not unveil the secrets of the site’s birth – its construction date.

A cursory search reveals that Hampshire archaeology has, intriguingly, reclassified Danebury as a Bronze Age relic. According to this new classification, “Evidence suggests that Danebury Iron Age Hill Fort was built 3000 years ago. It started life as a Late Bronze Age stock enclosure, while the main defences that are now visible were constructed around 2500 years ago. The fort continued to be in use until around 100 BC, a century and a half before the Roman invasion of AD 43.”

The basis for this shift in classification can be traced to carbon dating, which exposed samples reaching as far back as 700 BCE, leading to the realisation that the site was never truly of the Iron Age.

In fact, during the extensive excavation conducted between 1969 and 1978, which included a rare examination of the ditches outside the fort, a treasure trove of flints spanning from the late Neolithic to the early Bronze Age was unearthed, along with a smattering of Beaker period pottery. Consequently, we find ourselves teetering on the precipice of a profound reevaluation, one that suggests that Danebury might not be Iron Age, nor Bronze Age, but quite possibly a relic from the Neolithic era. The ability to definitively differentiate Neolithic flints from their Mesolithic counterparts is a matter that deserves thorough exploration, even if it may lead us to reject some preconceived notions.

Moreover, the excavations carried out at Danebury between 1979 and 1988 yielded an impressive assemblage of flints, totalling 2,896 items. It is of paramount importance to note that these archaeological endeavours unveiled a linear earthwork. The contours of this earthwork had been accentuated by a worn hollow trackway (F295), reaching a depth of approximately 0.3 meters behind the ditch on the northern side. Regrettably, the age of this feature remains elusive, but it’s conceivable that this trackway might constitute one of the original routes leading to the fort’s entrance.

A striking observation made possible by LiDAR technology, although unmentioned in the report, is the linkage between this ‘Dyke’ and the outer ditch of the site. This intriguing connection hints at the possibility of a nautical route to the site, presumably navigable during higher river levels in prehistoric times.

So it’s Prehistoric and not Iron Age – therefore is it a hillfort at least?

In our quest to ascertain whether this site was initially conceived as a ‘fortification,’ we must examine two critical aspects: its original design and the practical function it served in the past. It is crucial to consider that, like many ancient structures, this site could have been adapted for a new function in later historical periods.

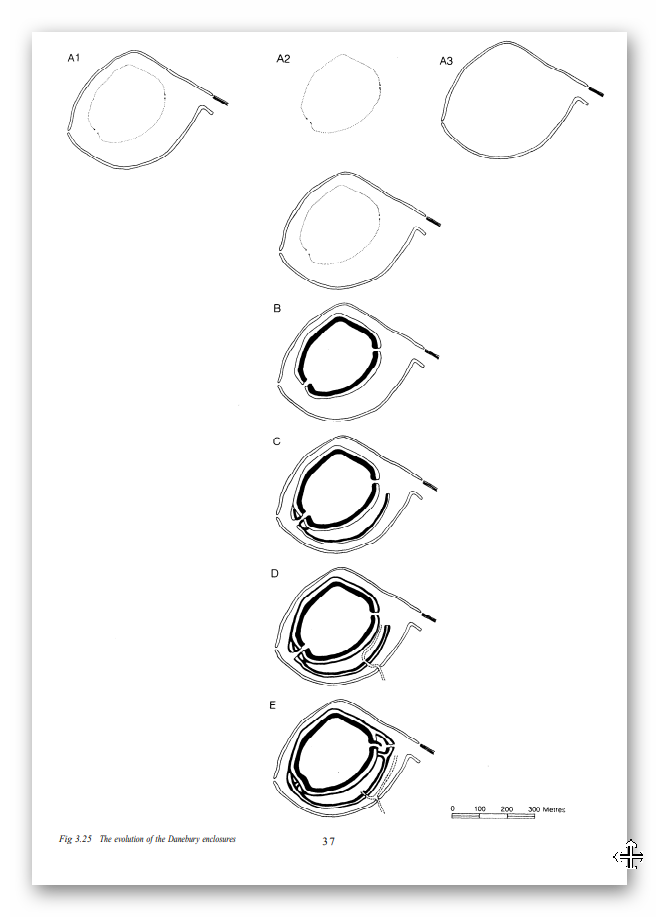

Official schematics detailing the phases of Danebury’s evolution shed light on its original design. Notably, the previously recognised ‘Linear Earthwork’ (Dyke) played a pivotal role in its construction, linking to another ‘defensive’ ditch, designated as A1. However, an intriguing twist emerges.

Regrettably, LiDAR technology uncovers a discrepancy in Barry Cunliffe’s illustrative depictions of the site. It appears that some creative liberties were taken in these drawings. The FULL linear feature was not only omitted from the diagrams but a somewhat exaggerated kink was added to the south of the Dyke, creating the impression of a deliberately planned entrance. In reality, this feature formed a complete circle and did not resemble the ‘banjo entrance’ that Cunliffe sought to convey. The reality is that the straight linear earthwork preceded the outer circle.

Additionally, it’s worth noting that the original ditch A1 appears to have had more earthwork material deposited on its outer section than on the inner portion. This particular characteristic, where more soil is added to the outer side, raises questions about its viability as a purely ‘defensive’ element.

So, Danebury is probably Neolithic/Mesolithic in date (shown by flint numbers on site) and not defensive as the original ditch was made probably to link a Linear Earthwork to the river system.

Let’s look at Maiden Castle to see if the ‘traditionalists’ have better luck with their hypothesis.

Maiden Castle – Case Study

According to Wikipedia – Maiden Castle is an Iron Age hillfort 1.6 mi (2.6 km) southwest of Dorchester, in the English county of Dorset. Hill forts were fortified hilltop settlements constructed across Britain during the Iron Age.

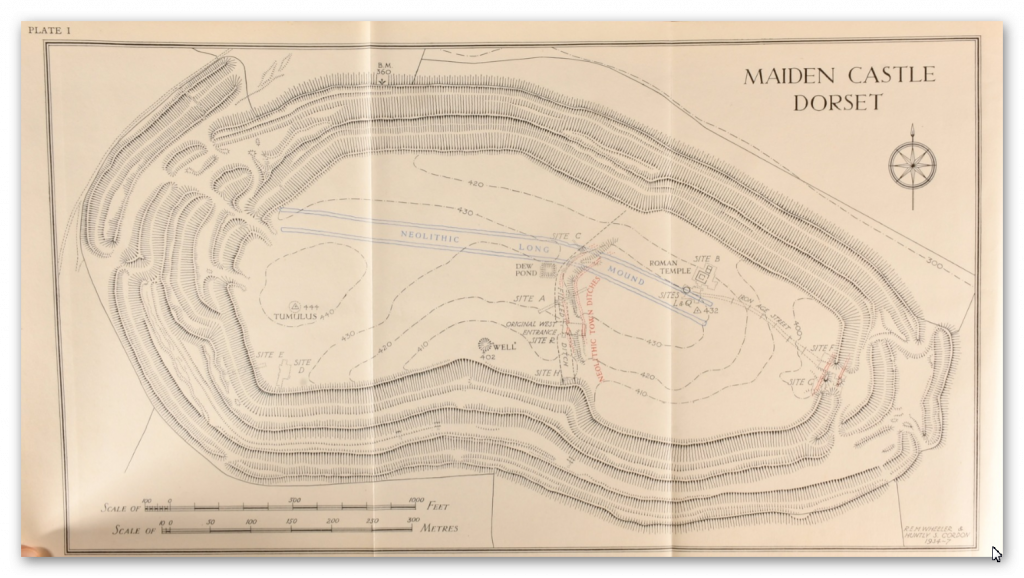

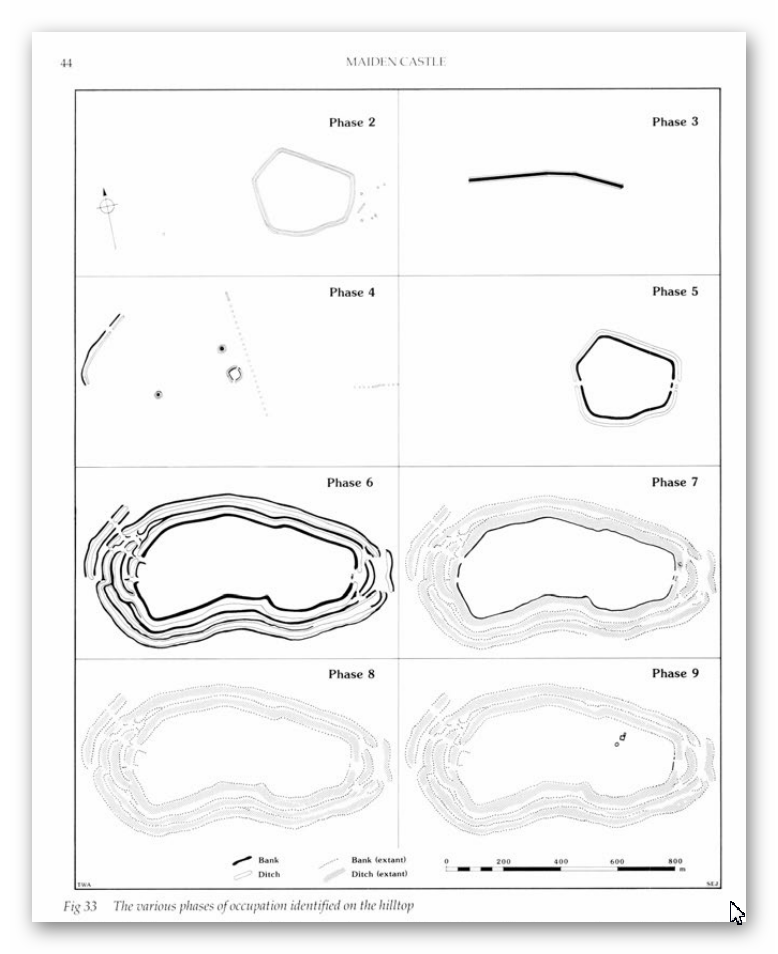

The earliest archaeological evidence of human activity on the site consists of a Neolithic causewayed enclosure and bank barrow. In about 1800 BC, during the Bronze Age, the site was used for growing crops before being abandoned. Maiden Castle itself was built in about 600 BC; the early phase was a simple and unremarkable site, similar to many other hill forts in Britain and covering 6.4 ha (16 acres).

Around 450 BC it was greatly expanded and the enclosed area nearly tripled in size to 19 ha (47 acres), making it the largest hill fort in Britain and, by some definitions, the largest in Europe. At the same time, Maiden Castle’s defences were made more complex with the addition of further ramparts and ditches. Around 100 BC, habitation at the hill fort went into decline and became concentrated at the eastern end of the site. It was occupied until at least the Roman period, by which time it was in the territory of the Durotriges, a Celtic tribe.

After the Roman conquest of Britain in the 1st century AD, Maiden Castle appears to have been abandoned, although the Romans may have had a military presence on the site. In the late 4th century AD, a temple and ancillary buildings were constructed. In the 6th century AD, the hilltop was entirely abandoned and was used only for agriculture during the medieval period.

The study of hill forts was popularised in the 19th century by archaeologist Augustus Pitt Rivers. In the 1930s, archaeologists Mortimer Wheeler and Tessa Verney Wheeler undertook the first archaeological excavations at Maiden Castle, raising its profile among the public.

Allow me to elucidate our quandary further. Recent excavations in the year 1985 revealed artefacts hailing not only from the Neolithic era but also from a substratum that likely originates in the Mesolithic epoch. Therefore, the label ‘Iron Age’ begins to appear somewhat askew.

The question arises: could this subsequent ‘addition’ truly be classified as a fortification?

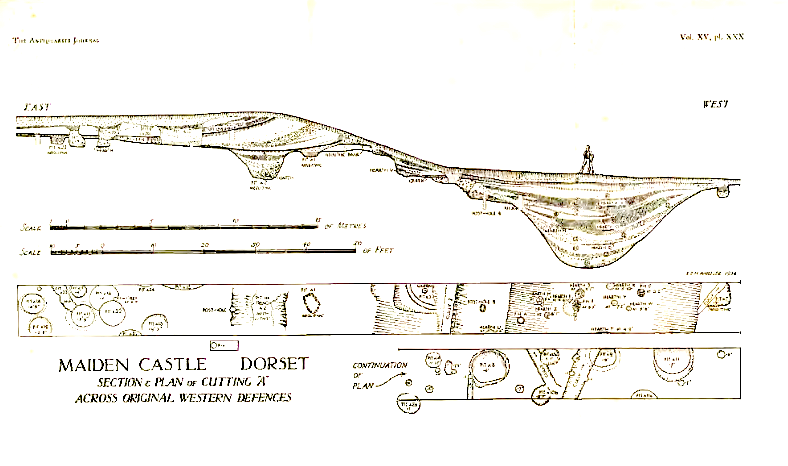

Our scrutiny of the construction once more casts doubt on this notion. The ditches, ostensibly designed for defence, present a conundrum. The sole cross-sectional glimpse into these ‘defensive’ trenches reveals an uncanny resemblance to the flat-bottomed counterparts witnessed in other prehistoric sites like Avebury, Stonehenge, and Old Sarum.

Maiden Castle and the Myth of the Massacre

Although Maiden Castle is often cited as evidence of Iron Age warfare, the archaeology paints a much more cautious picture.

- Only a small number of burials were found near the entrances — not mass graves.

- Among these:

- One adult male had a projectile wound in his spine (originally thought to be a Roman ballista bolt, now debated).

- One young woman showed signs of trauma.

- Several children were also buried — not typical combatants.

Most bodies show no direct evidence of violent death.

There is no layer of battlefield debris, no mass trauma event consistent with a large-scale siege.

Moreover:

- Over 20,000 slingstones were found stored near the entrances, but their exact purpose remains uncertain. They could represent defensive stockpiles, but also hunting tools, ritual offerings, or symbols of authority.

- After the supposed Roman assault, Maiden Castle was largely abandoned — suggesting it was not a viable military stronghold, but rather a symbolic centre caught up in a violent moment of change.

In short:

- One tragic encounter at the end of Maiden Castle’s life does not prove it was built or primarily used as a fortress.

The evidence supports a more complex reality:

Maiden Castle was a trading or community meeting site, possibly adapted hastily for defence when Roman forces arrived — but defence was not its primary, original function.

The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

Introduction

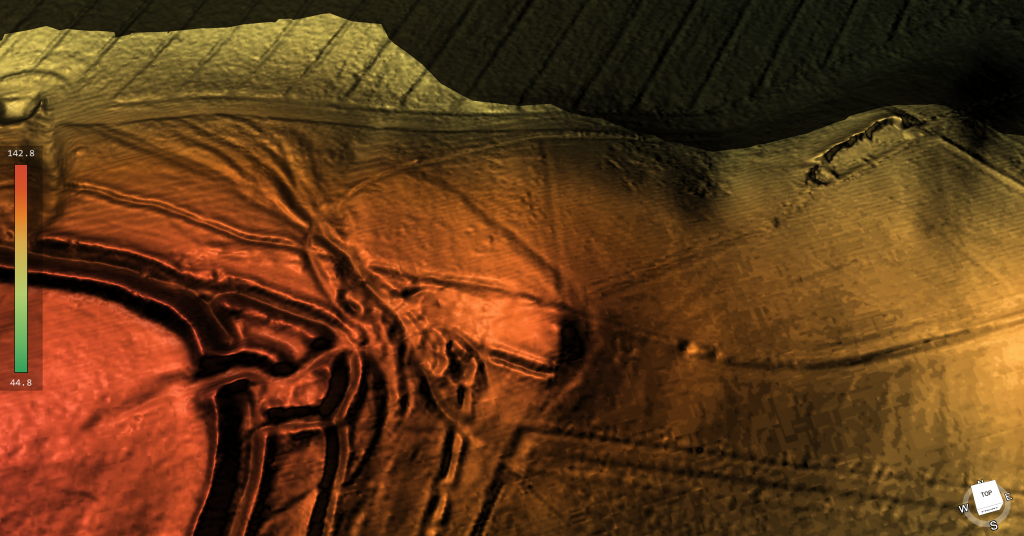

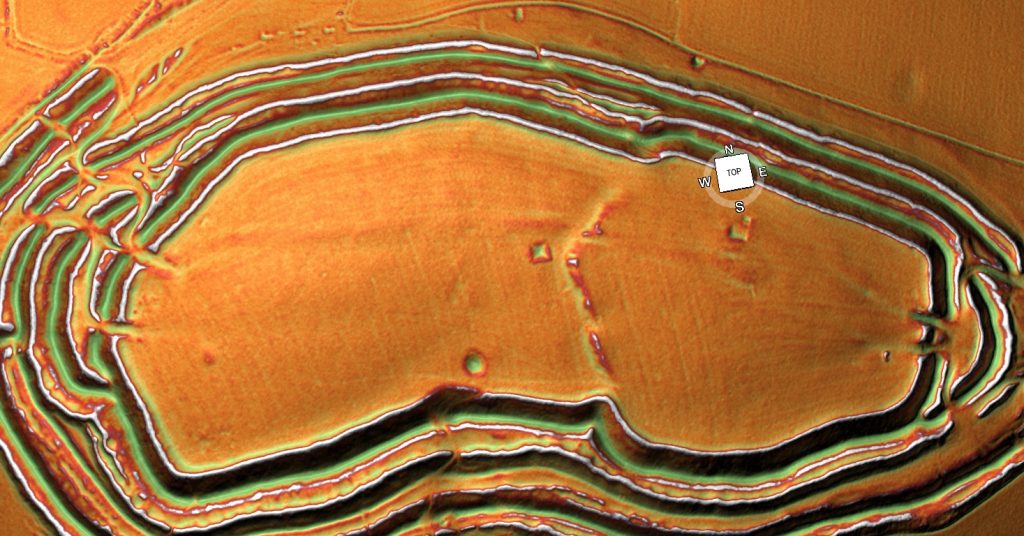

Maiden Castle, Britain’s largest Iron Age hill fort, has always been a subject of fascination and mystery. Its impressive size and strategic location suggest it was once a significant military stronghold. However, recent advancements in archaeological technology, specifically Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), have sparked debates about the actual feasibility of defending such a vast fortification by examining the logistical requirements necessary to sustain a large garrison here, juxtaposed with the lack of physical evidence for such activity, a new narrative emerges, challenging traditional interpretations of Maiden Castle’s historical significance.

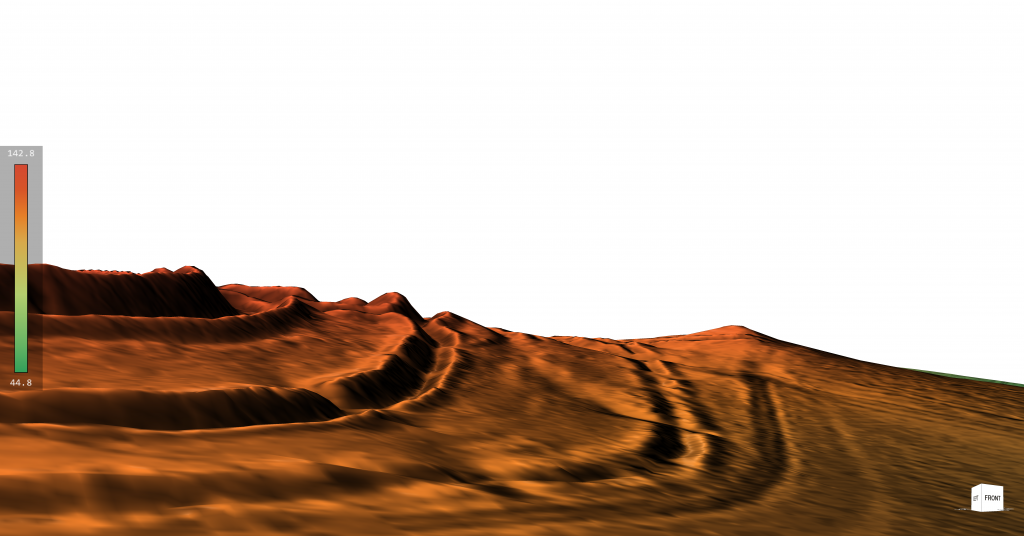

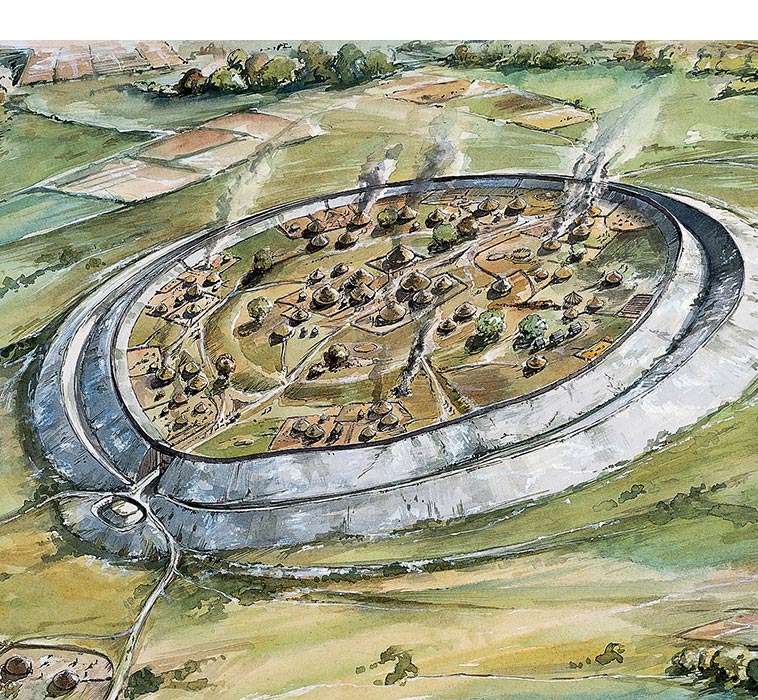

The Scale of Maiden Castle

Maiden Castle sprawls across approximately 47 acres, making it one of Europe’s most extensive hill forts. Historically, it’s been portrayed as the last stand of the Britons against the Romans, implying it once hosted a substantial military force. The sheer size of the fortification would require significant human resources to defend and maintain, not to mention the extensive support system needed to sustain such a force over prolonged periods.

Estimating Defence Manpower

Based on the fort’s perimeter, an estimated 155 soldiers per shift would be necessary to effectively guard it, assuming a strategic placement of one soldier every 10 meters. This calculation triples to 465 soldiers when considering three shifts to cover 24-hour defense, without considering the rotation of these soldiers. In comparison, the Roman town of Londinium had 1,000 soldiers to protect it and a supporting population of 30,000 people.

Logistical Support Requirements

Supporting a garrison of this size is no minor feat. Each soldier would require at least 3,000 calories daily, amounting to over 171 million monthly calories for the entire personnel. This would necessitate large-scale food provisions, including grains and meat, which would require extensive storage and preservation facilities.

Water Supply Challenges

One of the most critical logistical requirements is water. For Maiden Castle’s estimated population of 1910 individuals (including soldiers, support staff, and their families), about 745,950 litres of water would be needed monthly – this equates to at least 15 large deep wells. Historical accounts and archaeological evidence must show substantial water sources, such as wells or water management systems, to support this figure.

The Missing Wells

However, LiDAR scans, which are highly effective at identifying even minute changes in landscape and topography, have not revealed evidence of the necessary 15 wells. The absence of such crucial infrastructure raises significant doubts about the sustained military use of Maiden Castle at the scale often depicted in historical narratives.

Livestock and Food Production

The logistics of feeding a large garrison would also involve livestock management. Approximately 516 animals would be required monthly for the meat supply alone, necessitating extensive grazing areas, enclosures, and management systems, none of which have been identified in the LiDAR data.

Manufacturing Weapons and Armour

A garrison’s effectiveness also depends on its ability to arm itself. Producing weapons and armour would require workshops, forges, and considerable quantities of raw materials, along with skilled craftsmen. The fort’s defence would necessitate a continuous supply of spears, arrows, and protective gear. Yet, there is no archaeological evidence of such industrial activity on a scale that the theoretical number of defenders would demand.

Lack of Residential Structures

Moreover, the housing needs (min. 250 structures) for a population this large would be substantial. If Maiden Castle were as populated and active as theorised, we would expect to find numerous residential structures. Yet, archaeological digs and surveys, including LiDAR imaging, have only identified a handful of houses to date, casting further doubt on the historical narratives of a densely populated fort.

The Problem of Evidence

The discrepancy between the logistical requirements for sustaining a significant military presence at Maiden Castle and the lack of physical evidence supporting such activities presents a profound challenge to traditional interpretations. The absence of infrastructure necessary for water, food, and weapon production suggests that either Maiden Castle was not primarily a military fort at the scale often imagined or our understanding of its historical role needs significant revision.

Alternative Theories

It’s possible that Maiden Castle served a different function, perhaps more to do with trading and hence the massive ditches that would have been moated in the past rather than a continuously manned military fortress. This would align more closely with the archaeological evidence, or lack thereof, and help explain the absence of extensive military infrastructure.

Conclusion

The enigma of Maiden Castle reflects the complexities of archaeological interpretation and the importance of integrating new technologies like LiDAR with traditional archaeological methods. The emerging picture is that the logistical viability of Maiden Castle as a large-scale military fortress is not supported by the physical evidence currently available. This case serves as a reminder of archaeological research’s dynamic and evolving nature, where new tools can significantly alter our understanding of the past.

Final Thoughts

As we uncover more about ancient sites like Maiden Castle, it is crucial to remain open to new interpretations and theories that might differ significantly from traditional views. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Still, it does require us to question and reassess historical assumptions, ensuring our understanding of the past is as accurate as possible.

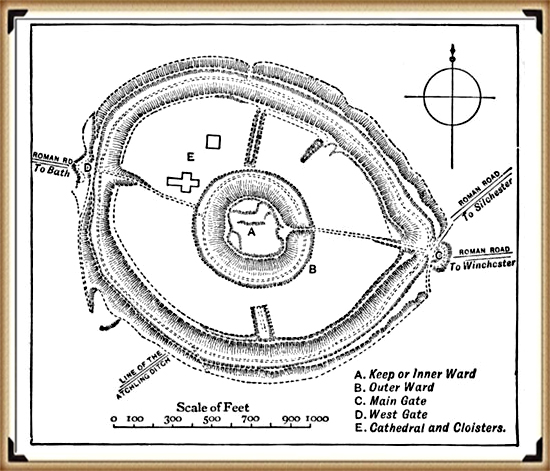

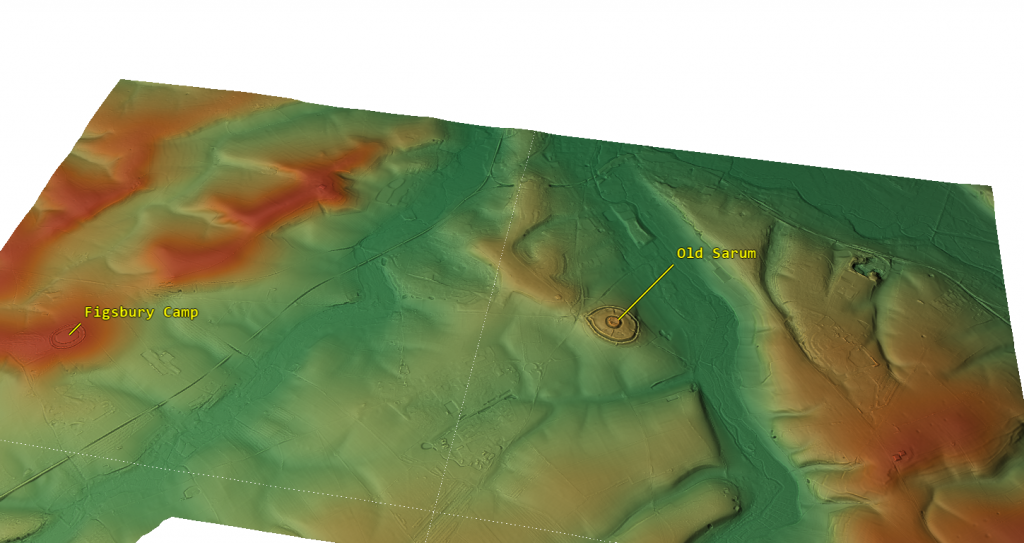

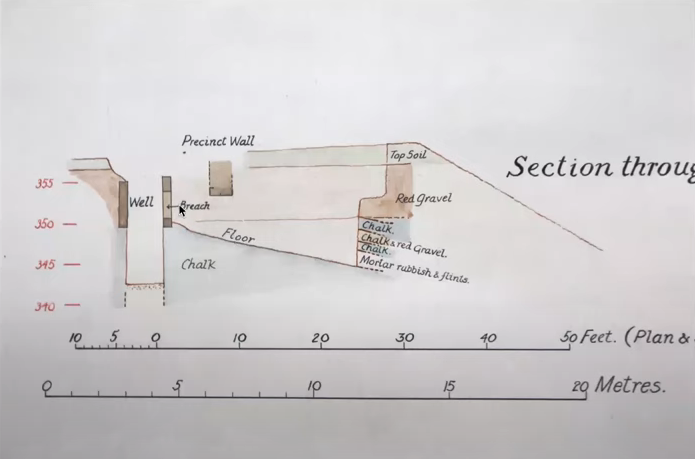

Old Sarum – Case Study

According to English Hertitage who own the site: Old Sarum is an ‘Iron Age hillfort’ may have been established here about 400 BC. It was then occupied shortly after the Roman conquest of Britain (AD 43), when it became known as Sorviodunum.

Three Roman roads from the north and east converged outside the east gate of the hillfort, and two sizeable Romano-British settlements were also established outside the ramparts. Little is known of this period, though it has been suggested that in the early Roman period a military fort was set up within the earthworks, with a civilian settlement outside. The civilian settlement formed the nucleus of one, or both, of the extra-mural Roman settlements. As the need for a fort dwindled, meanwhile, the area within the ramparts was converted to become the precinct for a Romano-British temple.

We have no evidence of the fate of Sorviodunum at the end of the Roman period, and the Anglo-Saxon period as a whole is poorly recorded. In 1003, however, a mint was sited within the old hillfort; and archaeological finds suggest there was late Anglo-Saxon settlement outside the ramparts. So there is evidence of life in and around Old Sarum before the Conquest.

In my view, oversimplified interpretations of the past, lacking excavation work to substantiate theories, pose significant challenges. Close examination often reveals fundamental flaws, such as the assumption of Roman roads converging and passing through a particular site. This type of desk-based archaeology, relying solely on OS maps and rulers, can lead to subjective conclusions.

The reality, as demonstrated by my own LiDAR investigation, contradicts these assumptions. The supposed road leading through the site to Bath is absent from both LiDAR maps and satellite photographs. Furthermore, considering the topography, it would be implausible for such a road to exist unless it were the largest land bridge in British Roman history.

It’s crucial to approach archaeological interpretations with a critical eye and to rely on comprehensive research methods to uncover the true complexities of the past. My LiDAR investigation highlights the importance of utilising advanced technologies and conducting thorough fieldwork to refine our understanding of historical landscapes.

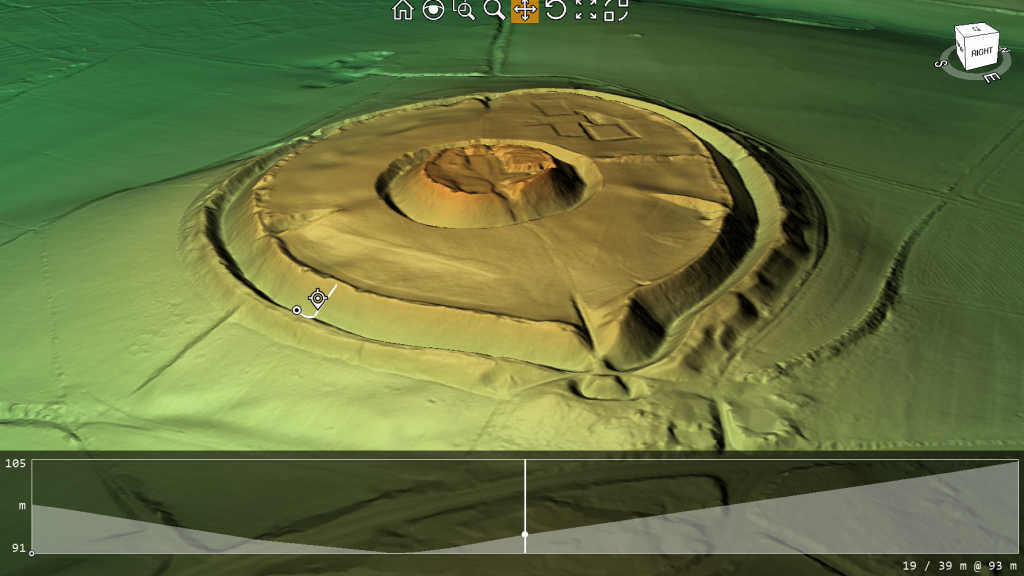

Is it a defensive structure?

In archaeology, I believe honesty is paramount. Categorising sites under broad labels like “Iron Age Forts” oversimplifies their complexities. Take Old Sarum, for instance—it’s situated in a floodplain on an island, not on a hill as commonly assumed. This challenges our traditional understanding of fortifications and prompts us to reconsider our interpretations.

The proximity of these supposed defensive forts raises another intriguing question. Why would communities invest considerable time and effort in building multiple forts close to each other? Considering the logistical challenges and the likely limited population of prehistoric Britain, it’s logical to question the necessity of such clustering.

Assuming that manpower was an unlimited and cost-free resource in ancient times is overly simplistic. It overlooks the practical considerations that would have influenced decision-making. By challenging these assumptions, we can gain a deeper understanding of prehistoric society. I believe it’s essential to critically examine these aspects of the past rather than accepting naive interpretations. Let’s strive for a more nuanced understanding that acknowledges the complexities of ancient societies and avoids oversimplification.

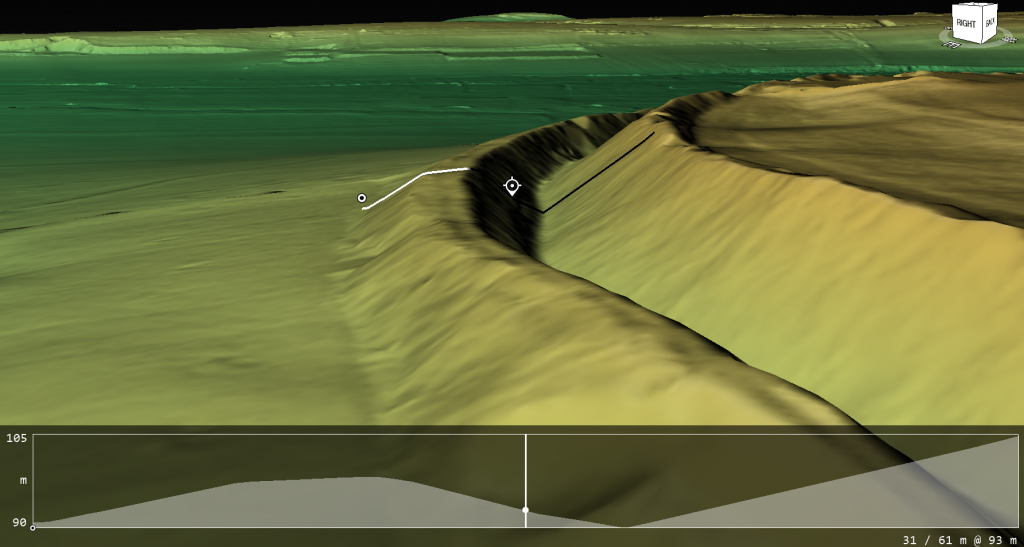

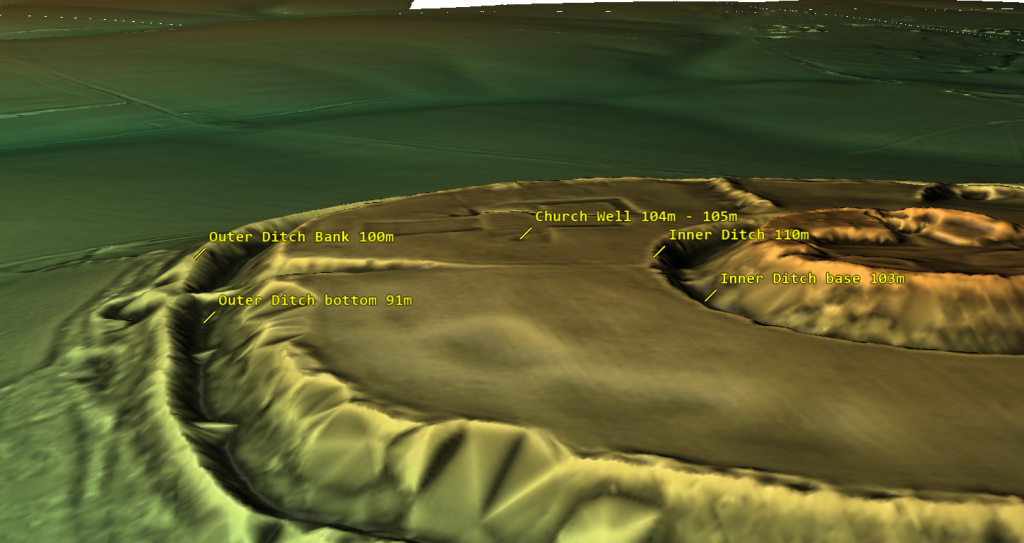

Outer Moat constructed to keep in water as a moat?

When we examine the site’s profile using lidar, two major findings become apparent. Firstly, the spoil from the ditch was placed on the outside rather than the inside (as expected if it was defensive), and the base of the spoil was not part of the natural rise of the floodplain, indicating that the outer part of the ditch is actually a bank.

Water Table

Based on the site’s historical records, we understand that one motive for relocating the church was its water shortage, leading it to tap into the deep well owned by the garrison. This knowledge allows us to assess the state of the moats and comprehend why the inner moat was excavated to a depth of 7 meters. By examining the well discovered during excavation, we ascertain that it was abandoned at a depth of 104m to 105m meters (OD), suggesting that any ditch below this level would have become waterlogged.

The initial depth of the inner ditch was 110 meters (OD), but today it measures 103 meters (OD), which is below the bottom of the Church well. Based on this data, we can scientifically hypothesize that during Norman times, the inner ditch was dug deeper to reach the water table level. It’s also possible that as the water supply for the moat decreased over the church’s lifetime, the moat was excavated unusually deep to access the diminishing water levels.

This new understanding of the water table also opens up the possibility that the outer ditch was also moated up to the Norman conquest and moreover, during the Roman period – this is something that needs urgent explaination and further study.

The Isle of Man Problem: 32 Hillforts, No War

The Isle of Man presents a striking case study.

Despite its small size (572 km²) and relatively low prehistoric population (likely no more than a few thousand people), the island hosts over 32 known hilltop enclosures.

- That’s one hillfort for every 5–6 square kilometres.

- Far more than necessary for true defensive refuges.

- Far too many for the small, scattered prehistoric communities to man, defend, or maintain.

Furthermore:

- There is no evidence of widespread conflict, siege layers, or mass trauma on the Isle of Man.

- The enclosures are clustered near coastlines, rivers, and quarry sites, suggesting trade, ritual, and social functions rather than fortress building.

In reality, these hillforts reflect:

- Regional gatherings,

- Resource management hubs,

- Territorial presence displays,

- And seasonal ritual activities.

They are part of a complex, multi-layered social system — not remnants of an island bristling with fortresses.

Economic Footprints: What Hillforts Left Behind

If hillforts had been functioning military garrisons, we would expect them to leave behind the kind of economic footprints we see at true military installations. Roman forts along Hadrian’s Wall, for example, show dense concentrations of:

- Lost coins (due to pay, gambling, markets),

- Trade goods,

- Personal items,

- Infrastructure like bathhouses, workshops, taverns.

Hillforts, however, show none of these patterns:

- Coin finds are extremely rare — even after coinage became widespread.

- No dense trade debris typical of garrison towns.

- No large, permanent marketplaces found inside or immediately outside the earthworks.

- No taverns, bathhouses, or public structures that would support a standing military population.

Instead, what we do find:

- Sporadic evidence of seasonal gatherings,

- Traces of animal enclosures and storage pits,

- Rare, isolated finds suggesting episodic use, not permanent occupation.

This economic silence reinforces the view that hillforts were not permanent defensive strongholds. They were seasonal gathering places, trading hubs, and symbols of regional power — adapted when necessary, but not built for war.

Comparison Chart

This is designed to hammer the point home very clearly:

| Feature | Roman Forts | Medieval Castles | Hillforts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Civilian housing (vicus or town) outside gates | Always present | Always present | Rare to none |

| Permanent occupation evidence (housing, workshops) | Dense and obvious | Dense and obvious | Minimal, sporadic |

| Water supply (wells, cisterns, springs) | Always present | Always present | Rare, problematic |

| Markets/trade hubs | Yes (vici markets) | Yes (castle markets) | Rare, indirect evidence |

| Coin loss patterns (economic footprint) | Heavy and dense | Heavy and dense | Very rare |

| Evidence of siege warfare (mass graves, trauma layers) | Occasionally | Occasionally | Very rare, disputed |

| Garrison infrastructure (barracks, granaries, armouries) | Clear and standard | Clear and standard | None |

| Ritual or ceremonial use | Minor | Minor | Major |

| Symbolic/territorial display | Minor | Minor | Major |

| Primary purpose | Military defence | Military defence | Multi-use social centre |

Conclusion

In light of radiocarbon re-dating, landscape logistics, environmental context, and the absence of widespread conflict archaeology, it is clear that the traditional interpretation of hillforts as purely defensive structures does not hold up.

Instead, hillforts were dynamic, multifunctional community centres:

- Places of trade,

- Seasonal gathering,

- Political negotiation,

- Social rituals,

- Resource management,

- And yes, occasional refuge during times of crisis.

The “hillfort hoax” is not merely a minor academic error — it represents a fundamental misunderstanding of the economic sophistication, social complexity, and territorial organization of prehistoric Britain and Ireland.

We must move beyond outdated, militaristic assumptions and embrace the true richness of these ancient landscapes.Curiously, signs of later defensive ditches emerge, and they bear a different, smaller, and V-shaped profile. Their purpose, it seems, was to ensnare any marauding adversaries. The round and conspicuously capacious ditches we encounter here bear a striking resemblance to a singular category of defensive structure in history – Norman Castles. The Normans, however, chose moats, not ditches, as their preferred defensive fortifications. An enigma indeed.

Might we be gazing upon prehistoric moats, which, in the bygone era of elevated water tables, would have readily filled to assume the characteristics of a moat? Could these have served as a defence, or might a more plausible function be inferred – a conduit for waterborne trade, facilitating the ingress of boats?

Finally, let us contemplate a pivotal factor, one I have thus far refrained from disclosing, for I deem it the most crucial piece of evidence, the ‘smoking gun,’ as it were, in our argument against the notion that these sites were constructed for defensive purposes. Not a solitary remains of a life extinguished in conflict has ever been unearthed within the confines of the ditches encircling any of the two thousand so-called ‘Iron Age Forts’ that punctuate history.

And just as importantly, the economic footprint — or lack of it — tells the same story.

Where real garrisons stand, coins, goods, and markets follow. In hillforts, we find quiet, temporary use: more in keeping with seasonal trade, ritual, and social gathering than the steady rhythms of a standing army.

What Archaeology Must Prove to Justify “Fort” Classifications

Given the overwhelming evidence presented here — logistical, economic, landscape, and archaeological — any continued classification of hillforts as primarily defensive must now meet clear evidential standards.

Specifically, archaeologists would need to demonstrate:

- Consistent presence of large residential structures (for permanent defenders),

- Multiple reliable and sustainable water sources (wells, cisterns) on site,

- Dense loss patterns of economic goods (coins, tools, trade items) indicating long-term garrison use,

- Associated civilian settlements outside gates (traders, farmers, artisans),

- Workshop remains for armour and weapon manufacturing,

- Defensible entrances with clear defensive layering (rather than just “complex” layouts),

- Widespread trauma or siege layers showing repeated military conflict,

- Evidence that original ditch and bank constructions were designed for defence (e.g., V-shaped ditches, inward-facing ramparts).

Without these elements — and so far, they are largely absent —

the default assumption should shift away from “fortifications” toward “multifunctional ceremonial, trade, and seasonal gathering sites.

You might want a final quick punchy line like:

It is an assertion that prompts us to reconsider their true nature, to entertain the possibility that these were not fortifications but, rather, bustling hubs of trade and commerce.

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence — and calling hillforts ‘forts’ today without extraordinary evidence is no longer credible archaeology.”

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

For active discussions on the findings of the TRILOGY and recent LiDAR investigations that are published on our WEBSITE, you can join our and leave a message or join the debate on our Facebook Group.

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Borehole Evidence of Post-Glacial Flooding

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked – Troy did not exist in Asia Minor, but in fact, the North Sea island of Doggerland

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

Pingback: Archaeology: A Bad Science? - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Radiocarbon dating reshapes the story of Maiden Castle’s Iron Age deaths | Noah News