Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

Contents

- 1 Introduction — The Britain You Know Is a Fake

- 1.1 1 — The Britain You Know Is Only 8,000 Years Old

- 1.2 2 — Stonehenge’s Bluestones Couldn’t Have Rolled Here

- 1.3 3 — Britain Once Had a Country Twice the Size of Wales — and Lost It Overnight

- 1.4 4 — Raised Beaches… Or the Fingerprints of a Flooded Britain?

- 1.5 5 — The Thames Was Once Seven Kilometres Wide

- 1.6 6 — The Isle of Wight Was Cut Off by a Flooded River Valley

- 1.7 7 — Somerset’s Levels Were a Salt-Water Swamp

- 1.8 8 — Stonehenge Stood on a Peninsula Fed by a Healing Spring

- 1.9 9 — Our “Iron Age Hillforts” May Be Older — and Wetter — Than We Think

- 1.10 10 — The Map in Your Head Is a Mirage

- 1.11 Conclusion — Redraw the Map. Rethink the Past.

- 2 Update

- 3 PodCast

- 4 Author’s Biography

- 5 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 6 Further Reading

- 7 Other Blogs

Introduction — The Britain You Know Is a Fake

(Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past)

We look at our hills, rivers, and coasts… and think they’ve always been there.

Stable. Permanent.

But that picture… is a lie.

At the end of the last Ice Age, Britain was a land in chaos.

Seas surged sixty metres higher. Rivers swelled beyond imagination. Entire countries… disappeared beneath the waves.

Archaeology often ignores this truth. Too many theories are drawn on a modern map — a map our ancestors would barely recognise.

After two decades of fieldwork and over two hundred and sixty research blogs, I can tell you: to understand prehistoric Britain… you must redraw it.

Here are ten things you probably didn’t know about the drowned, shifting, waterlogged world our ancestors truly lived in.

1 — The Britain You Know Is Only 8,000 Years Old

When the Holocene began, Britain wasn’t an island.

A land bridge linked us to Europe — until rising seas finally severed it around six thousand BCE.

The change wasn’t gentle.

Meltwater pulses sent the tide racing inland, flooding valleys in years… not centuries.

Sea levels rose faster than our worst climate forecasts for 2100.

Every coastline shifted. The mouth of the Thames moved inland. Estuaries formed where farmland now lies.

Your hometown… could have been seabed

If you stood there then, your mental map of Britain would be unrecognisable.

The “island nation” idea? A very recent reality.

For most of prehistory… Britain was part of a wider European landscape.

2 — Stonehenge’s Bluestones Couldn’t Have Rolled Here

The romantic image is familiar: teams of men with ropes and ox-carts dragging stones two hundred kilometres from Preseli to Salisbury Plain.

But around eight thousand BCE, ninety percent of that “route” was deep wildwood.

Valleys in between? Bog-soaked mires.

Wheels would have sunk without a trace.

The real transport network wasn’t overland — it was water.

Seasonal floods. Frost-hardened winter ground. And above all… rivers.

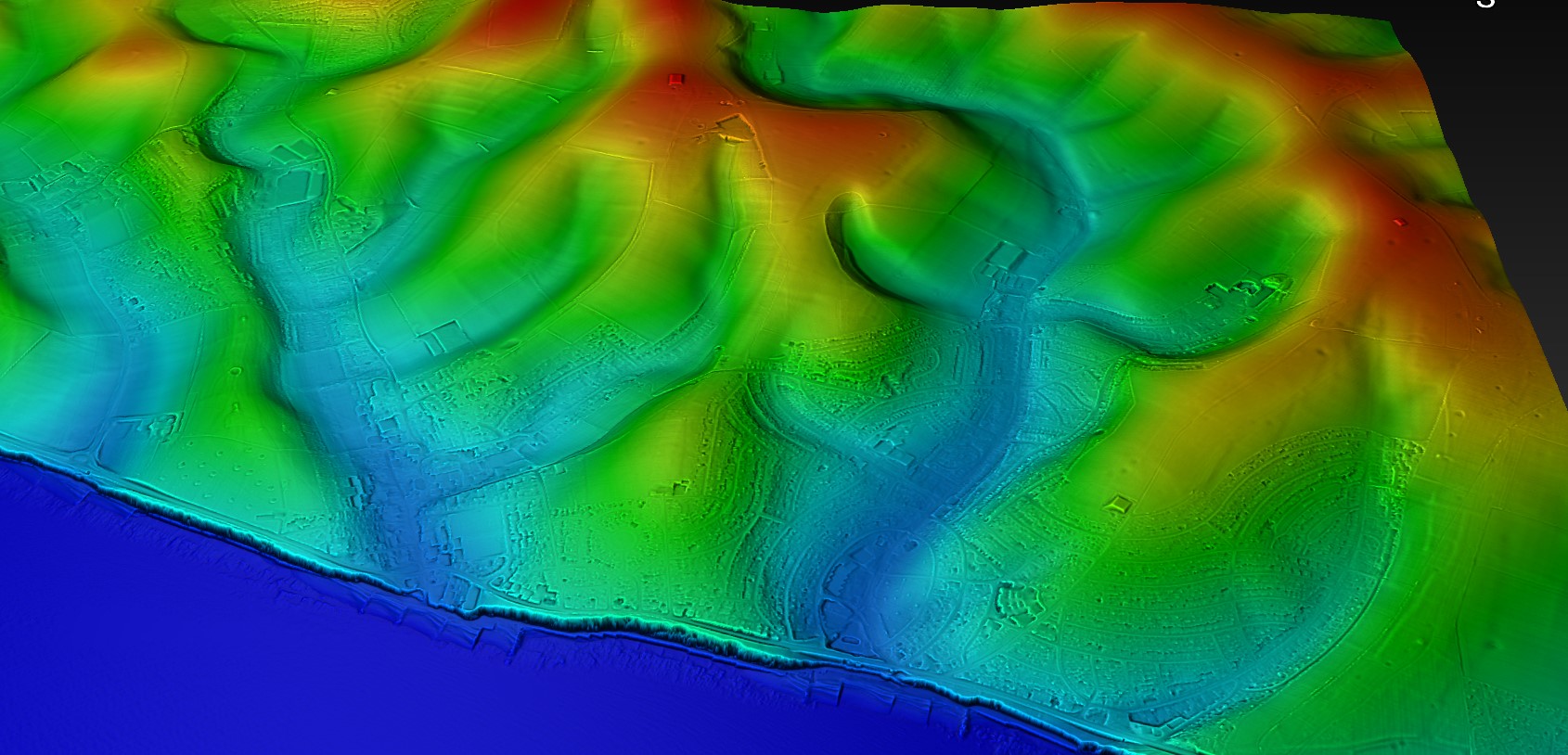

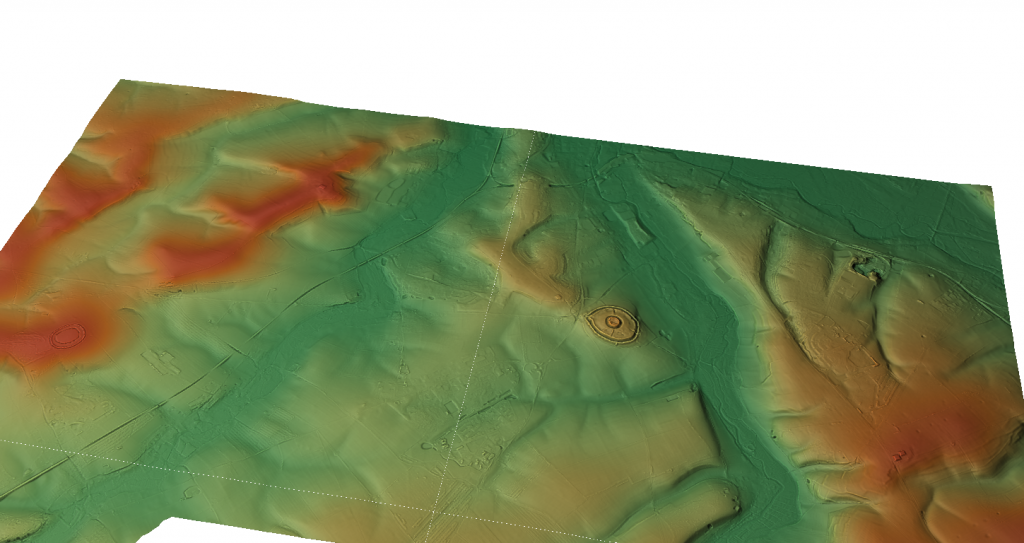

LiDAR mapping shows prehistoric waterways were the true highways.

This single fact changes the Stonehenge story entirely.

It wasn’t a land-locked haul of brute force — it was a calculated, water-based operation using the landscape to its advantage.

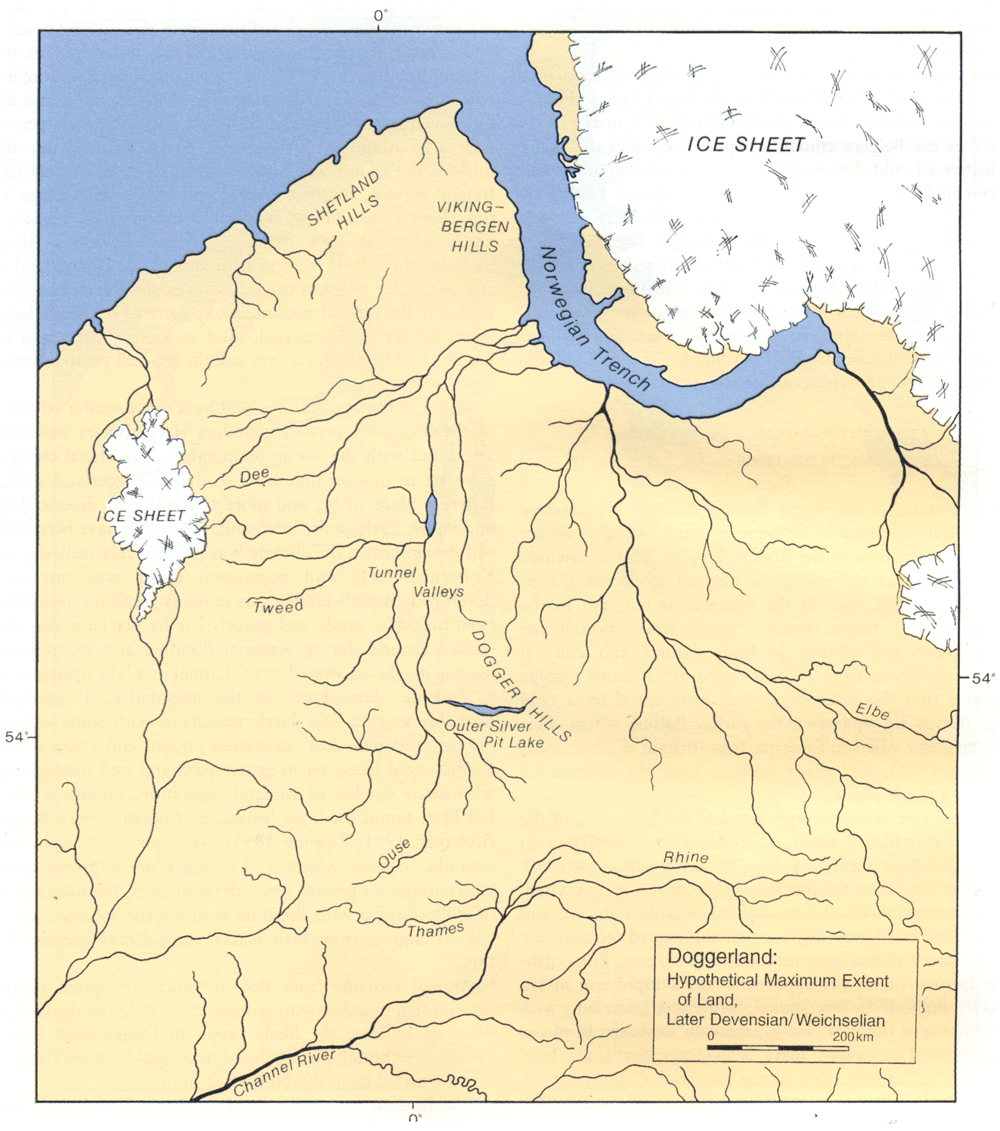

3 — Britain Once Had a Country Twice the Size of Wales — and Lost It Overnight

Doggerland was no myth. It was a vast lowland stretching from East Anglia to the Netherlands.

Its marshes, rivers, and lakes supported thousands of people. For centuries, it was a bridge between Britain and Europe.

Then it drowned. Whether through steady sea rise, sudden flooding, or both — the result was the same.

Communities found themselves separated by water where there had once been solid ground.

That shock forced a new reality.

Boats were no longer optional… they were survival.

In my Maritime Diffusion Model, this moment explains why megalithic architecture suddenly spread so quickly along Atlantic coasts — the sea became the new road.

4 — Raised Beaches… Or the Fingerprints of a Flooded Britain?

On Britain’s south coast, geologists point to “raised beaches” — sand and gravel layers perched far above today’s tide line.

The standard explanation is a mix of ancient shorelines and “isostatic rebound.” But the data… doesn’t match the story.

My research shows these aren’t fossil beaches at all. They’re concave, river-shaped deposits.

They sit under layers of unstructured chalk — exactly what you’d expect if catastrophic meltwater floods carved paleochannels down to the sea.

British Geological Survey maps confirm the pattern: huge branching flows, not static coastlines.

Once you see it, you can’t unsee it.

These are not tranquil remnants of a higher tide… they are scars of a country in flood</emphasis>.

And they tell a far more dynamic, violent story than the textbooks admit.

5 — The Thames Was Once Seven Kilometres Wide

Beneath London, boreholes reveal up to ten metres of early-Holocene silt.

This was not the neat, channelled Thames we know — it was a vast, braided tidal delta up to seven kilometres across.

Such a river wasn’t just wider… it was a different creature entirely.

Settlements clung to the high ground like islands. Boats connected them. Trade and travel followed water channels, not overland tracks.

This wasn’t an obstacle — it was a superhighway.

And here’s the myth-buster: London’s lack of prehistoric sites isn’t due to modern building wiping them out.

LiDAR shows that much of the Thames Valley floor was too wide and flood-prone to build on.

Only a few habitable high points existed — the places we now call the “Home Counties.”

6 — The Isle of Wight Was Cut Off by a Flooded River Valley

The Solent started as a river.

Then, around seven thousand five hundred years ago, rising seas burst through the valley, flooding it completely.

A short walk became an open-water crossing — and life on both sides changed overnight.

Suddenly, trade required boats. Communities reorganised. Control of crossing points likely meant influence and power.

Archaeology along the submerged Solent shows drowned forests, hearths, and even worked timbers… frozen in place beneath the waves.

Most extraordinary of all is Bouldnor Cliff.

Here, eleven metres underwater, lies the world’s first known boat-building site — a sixth-millennium BCE harbour that imported Einkorn wheat from mainland Europe.

This was no primitive backwater… it was a maritime hub centuries ahead of its time.

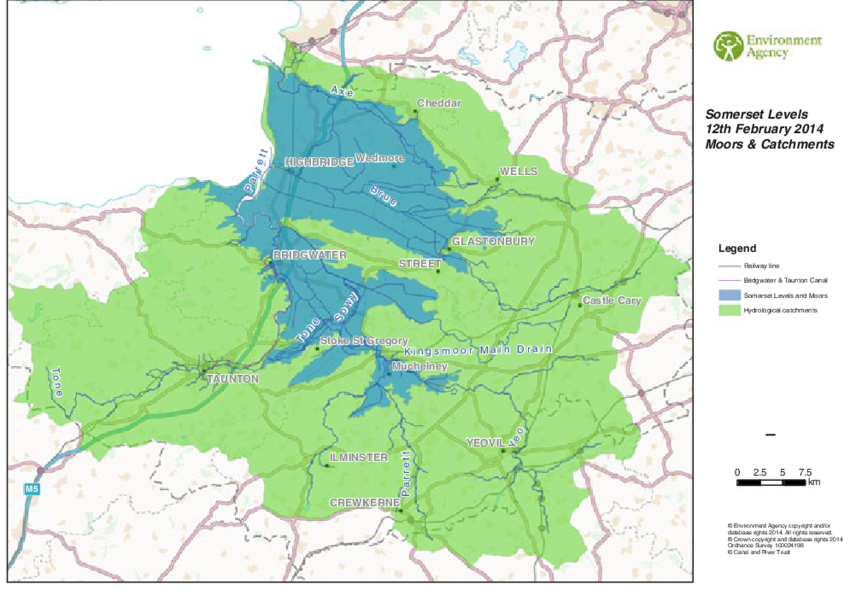

7 — Somerset’s Levels Were a Salt-Water Swamp

Between 5600 and 4450 BCE, the Somerset Levels were not the patchwork of fields we know today.

They were alder-carr woodland slowly drowning under advancing salt marsh.

Peat cores show the shift layer by layer — from fresh water to brackish tidal intrusion.

To prehistoric people, this meant constant adaptation: moving camps, changing food sources, finding safe ground.

Centuries later, societies would turn this swamp into a managed landscape of canals and raised trackways.

But in its early days, it was a shifting, dangerous maze of water… a place that could swallow your settlement in a season.

8 — Stonehenge Stood on a Peninsula Fed by a Healing Spring

Stonehenge didn’t stand beside a ceremonial pool or a “ritual lagoon.”

It was built on a peninsula jutting into the River Avon, fed by a natural spring at Stonehenge Bottom.

This fresh, flowing water made the site an ideal meeting place and a reliable refuge.

The bluestones, brought from Preseli, were more than decorative.

They contain minerals with natural antibacterial properties.

In a world where sepsis from a cut could be fatal, those stones were medicine.

Water from the spring flowing past them created a setting believed to aid recovery from infections and wounds.

Forget the star-gazing theories — Stonehenge was a healing centre, built with purpose and grounded in survival.

9 — Our “Iron Age Hillforts” May Be Older — and Wetter — Than We Think

From the air, hillforts look like defensive enclosures.

But LiDAR tells a different story — many sit in wet, low-lying areas with evidence of ditches that once held water.

These weren’t forts braced for battle… they were moated settlements designed for trade and control of water routes.

In a wetter prehistoric Britain, that was often more important than any wall.

Re-examining these sites with hydrology in mind reveals a network of connected hubs — places where goods, people, and ideas moved not along ridge-tops, but through waterways.

It’s a complete rethink of “forts” as we know them.

10 — The Map in Your Head Is a Mirage

When we think of Britain, we picture a static shape — familiar coastlines, steady rivers.

But in prehistory, those lines were always on the move.

Rivers cut new paths. Valleys flooded. Islands appeared and vanished.

The Britain of twelve thousand years ago was nothing like the Britain of eight thousand years ago — and both were strangers to the Britain we know now.

The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis forces us to redraw that mental map.

Once you do, everything changes — from how Stonehenge was built, to why Doggerland mattered, to the true nature of “hillforts.”

It’s not just a new map… it’s a new past.

Conclusion — Redraw the Map. Rethink the Past.

Prehistoric Britain was not a gentle green land.

It was a place of rapid change, flooded valleys, and disappearing coasts.

Ignore that… and you get bad archaeology.

Factor it in — and new explanations open up for the monuments, settlements, and journeys of our ancestors.

The evidence is there. The map is wrong.

<emphasis level=”moderate”>It’s time to set it right</emphasis>.

Update

Where to see Britain’s post-glacial high water table

The caves are the evidence. Karst systems preserve the height of former water tables:

Mendip Hills (Cheddar Gorge / Wookey Hole): Relic phreatic levels high above modern flow routes show earlier pressurised groundwater; silted tubes and scallops mark sustained high head after deglaciation.

Yorkshire Dales (Malham–Ingleborough): Abandoned risings and perched conduits around Malham Cove & Gaping Gill record higher Holocene heads; modern springs sit lower as the aquifer discharged over millennia.

Peak District (Castleton): Upper fossil passages in Peak Cavern/Speedwell are stranded above active streams—classic regression from a post-glacial high stand.

Chalk Winterbournes (Downs/Chilterns): The Misbourne, Chess, Kennet headwaters and Dorset winterbournes switch on when the head rises—same physics, small timescale. Early Holocene = the “on” position for much longer.

Chalk dew-ponds: Longevity on permeable chalk relies on self-sealing skins—the same lining behavior that helps Phase-1 Stonehenge’s moat retain water under high head.

Why this matters for Stonehenge Phase 1

Mechanism: High head + chalk colmation = standing water in the ditch.

Analogue: Cave high-stands are the geological logbook of that head.

Fit: The moat enables the mineralised bluestone baths and excarnation workflow documented in the Phase-1 model.

Quick Evidence: Britain’s Aquifers, Made Visible

Karst plumbing on show. In chalk/limestone belts, groundwater carved conduits, phreatic tubes, risings, and sinkholes—the aquifer made visible in places like the Mendips, Yorkshire Dales, and the Peak District.

High-stand markers. Abandoned phreatic passages perched high on cave walls, scalloped ceilings (pressurised flow), and silt beds record past water-table positions—higher than today during the early Holocene.

Seasonal analogue. Modern winterbournes (dry valleys that flow only when the head rises) prove the mechanism: when the potentiometric surface sits above cut level, water holds—exactly what Phase 1 required.

Self-sealing ditches. Fresh chalk cuts develop clay/carbonate skins (colmation), reducing leakage. With high head + recharge, a “ditch” becomes a moat.

PodCast

Author’s Biography

Robert John Langdon, a polymathic luminary, emerges as a writer, historian, and eminent specialist in LiDAR Landscape Archaeology.

His intellectual voyage has interwoven with stints as an astute scrutineer for governmental realms and grand corporate bastions, a tapestry spanning British Telecommunications, Cable and Wireless, British Gas, and the esteemed University of London.

A decade hence, Robert’s transition into retirement unfurled a chapter of insatiable curiosity. This phase saw him immerse himself in Politics, Archaeology, Philosophy, and the enigmatic realm of Quantum Mechanics. His academic odyssey traversed the venerable corridors of knowledge hubs such as the Museum of London, University College London, Birkbeck College, The City Literature Institute, and Chichester University.

In the symphony of his life, Robert is a custodian of three progeny and a pair of cherished grandchildren. His sanctuary lies ensconced in the embrace of West Wales, where he inhabits an isolated cottage, its windows framing a vista of the boundless sea – a retreat from the scrutinous gaze of the Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, an amiable clandestinity in the lap of nature’s embrace.

(The Stonehenge Code)

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

(The Stonehenge Code)

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

(The Stonehenge Code)

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unraveling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?