Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

Contents

- 1 Preamble

- 1.1 1. Introduction

- 1.2 2. The Traditional Theories

- 1.3 3. Where Theory and Reality Diverge

- 1.4 4. The Enigma of Offa’s Dyke

- 1.5 5. Misreported Defensive Features

- 1.6 6. Gaps and Their Implications

- 1.7 7. Simpler Methods: The Humble Fence

- 1.8 8. Living Hedges as Boundaries

- 1.9 9. The Great Hedge of India

- 1.10 10. Walls and Fortified Edges

- 1.11 11. Roman Frontier Systems

- 1.12 12. Enclosure and Boundary in Early Modern Britain

- 1.13 13. Unusual Alignments and Topography

- 1.14 14. Reimagining Their Purpose

- 1.15 15. Toward a Deeper Understanding

- 2 Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- 3 Introduction

- 4 2025 Update

- 4.0.1 Historic England Confirms the Prehistoric Origins of Britain’s Linear Earthworks

- 4.0.1.1 Why Offa’s and Wansdyke Are Not Saxon Ditches

- 4.0.1.2 1. Historic England’s Own Words

- 4.0.1.3 2. Confusion by Reuse

- 4.0.1.4 3. Historic England Admits Mis-Dating Risks

- 4.0.1.5 4. Functional Variety, Not Fortification

- 4.0.1.6 5. The Official Timeline

- 4.0.1.7 6. What This Means

- 4.0.1.8 7. A New Understanding

- 4.0.1.9 Conclusion

- 4.0.1 Historic England Confirms the Prehistoric Origins of Britain’s Linear Earthworks

- 5 Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

- 6 Further Reading

- 7 Other Blogs

Preamble

I’ve published numerous blogs about prehistoric canals, emphasizing how traditional academia has repeatedly overlooked and misunderstood these remarkable features. Because I’m both a scientist and a technology enthusiast, I rely on AI as an invaluable tool to streamline my reasoning and present it in a way that readers from different backgrounds can appreciate. In this particular blog, I’m using AI to illustrate that conventional explanations for earthworks are likely flawed and need a thorough reexamination. Finally, I’m including a reference to my earlier work so readers can see how my new insights build on past research. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

1. Introduction

Linear earthworks have mesmerized observers and archaeologists for generations. From Offa’s Dyke to Wansdyke, these elongated banks and ditches are typically explained as either military fortifications or boundary markers. Yet modern LiDAR surveys, fresh archaeological insights, and comparisons to simpler and more visible boundary methods raise serious doubts about those interpretations. Rather than straightforward defensive lines or frontiers, these earthworks display inconsistencies—missing sections, reversed ditches, and puzzling alignments—that challenge everything we thought we knew. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

2. The Traditional Theories

For much of the 20th century, scholars argued that linear earthworks served one of two main functions: to repel invaders or to mark out political or tribal boundaries. Cyril Fox famously claimed Offa’s Dyke was built by King Offa of Mercia to keep the Welsh at bay, supposedly placing the ditch on the Welsh-facing side. Others suggested that massive earthworks like Wansdyke indicated territory lines, visually announcing where one kingdom ended and another began. In these narratives, the structures were well-defined, continuous, and purposeful. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

3. Where Theory and Reality Diverge

Recent research has, however, underscored irreconcilable contradictions between theory and reality. Surveys indicate that many linear earthworks fail to maintain consistent ditches facing the purported enemy, contradicting the defensive premise. If these ditches were indeed built to ward off a threat, the alignment should be uniform. Meanwhile, if they were intended as boundary markers, gaps and missing stretches would logically undermine their entire purpose. Such discrepancies point to deeper complexities or altogether different functions. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

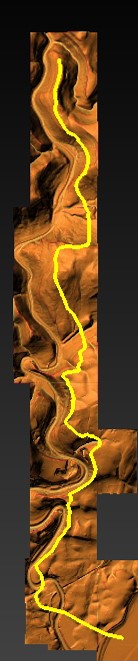

4. The Enigma of Offa’s Dyke

Offa’s Dyke is often touted as Britain’s largest linear earthwork, running roughly along the England–Wales border. Yet LiDAR surveys by researchers like Robert John Langdon reveal that nearly 60% of the structure is missing—lost to erosion, re-landscaping, or never built at all. Wide breaks exist for miles, making it hard to envision it as a single unbroken defensive or boundary line. Moreover, some ditches face in contradictory directions or do not match the typical expectation for a militaristic barrier, casting doubt on Fox’s original claim. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

5. Misreported Defensive Features

Part of the confusion lies in Cyril Fox’s early 20th-century reporting. He described consistent ditch placements, but modern scrutiny shows that some are misaligned. Whether unintentional errors or confirmation bias, Fox’s descriptions have dominated academic discourse for decades. Only with modern technologies—like LiDAR and detailed aerial photography—have we begun to see how many segments contradict his drawings. These findings force us to question the once authoritative notion that Offa’s Dyke was unambiguously a martial structure. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

6. Gaps and Their Implications

Wansdyke, second only to Offa’s Dyke in fame, also features significant gaps and disjointed sections. If linear earthworks were built at massive expense of time and labor to keep out invaders or mark territory, it is odd to see such discontinuity. A truly effective boundary marker, for instance, would leave no question of ownership or alignment. The existence of large “holes” in both Offa’s Dyke and Wansdyke conflicts with the fundamental idea that these were continuous frontier systems. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

7. Simpler Methods: The Humble Fence

Historically, many societies addressed boundary needs in more efficient ways. For instance, fences—wooden posts and rails—are cost-effective, require minimal labor, and can be erected swiftly. These have been used around the world for farmland demarcation and livestock control. Compared to the colossal task of digging a deep ditch and piling an earthen bank, a simple fence stands out as both quicker and cheaper. So if Saxons or Britons needed a practical boundary, why opt for massive earthworks instead of lower-effort alternatives? (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

8. Living Hedges as Boundaries

In much of Medieval and Early Modern England, living hedges—often composed of hawthorn or blackthorn—provided robust, natural fences. They had the advantage of growing denser over time, deterring both trespassers and stray animals. The ecological benefits were a bonus. Unlike ditches, which can become silted and invisible, a carefully maintained hedge remains an obvious and impenetrable barrier. Again, this begs the question: if clarity and cost-effectiveness were paramount, why dig a ditch that’s prone to erosion and difficult to maintain? (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

9. The Great Hedge of India

The British-led Great Hedge of India in the 19th century offers an extreme example: a massive thorny barrier stretching hundreds of miles to enforce salt taxes. Though not precisely a “fence,” it underscores how a dense thicket can effectively channel or block human movement, often more reliably than an earthen ditch. Historical records of this hedge’s success in preventing smuggling illuminate that highly visible, well-maintained barriers are more functional than large-scale but patchy earthworks. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

10. Walls and Fortified Edges

Other cultures have opted for monumental walls—be it Hadrian’s Wall in northern England or segments of the Great Wall of China. In both cases, the walls remain unmistakable even centuries later. They combine visibility, tangible presence, and durability. A ditch, by contrast, can be reabsorbed into the landscape relatively quickly, leaving only subtle impressions. If the goal was an unmistakable boundary or strong defense, these stone or brick structures seem more suitable than a meandering earthen rampart with frequent gaps. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

11. Roman Frontier Systems

The Romans perfected the art of boundary lines with the Limes Germanicus—a system of watchtowers, palisades, forts, and sometimes ditches. Here, the ditches were auxiliary; the main statement of control came from a visible wall or wooden fence line, reinforced by active garrisons. If Offa’s Dyke or Wansdyke were truly boundary lines in the Roman or later medieval sense, we might expect corresponding watchtowers or regular station points. The absence of such features in many linear earthworks adds another layer of skepticism about their supposed frontier function. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

12. Enclosure and Boundary in Early Modern Britain

Between the 15th and 19th centuries, Britain saw waves of enclosure, where open fields were divided by hedges or stone walls. This was cheaper and clearer for indicating ownership than earthworks. Visible markers helped landowners enforce property rights and control livestock. While these enclosures left an indelible mark on the British countryside, they did not involve monumental ditches. Thus, practicality and economic sense consistently drove fence- and hedge-building, implying that earthen dykes might have served a different, more specialized purpose. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

13. Unusual Alignments and Topography

Returning to the dykes themselves, one finds confusing topographical alignments. Sections may run halfway down a hill rather than atop its crest, or snake around in near-circles (like Grim’s Ditch in Oxfordshire), defying the notion of a straightforward boundary or a defensive rampart commanding high ground. If these were serious military structures, they would naturally seek topographical advantage; if they were boundary markers, they would favor maximum visibility. Neither condition is consistently met. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

14. Reimagining Their Purpose

Given these problems, many modern researchers—Robert John Langdon among them—propose that some linear earthworks are significantly older than the Roman or Saxon periods. They might have served ritual, symbolic, or even water-management functions in a prehistoric context. Comparisons to simpler boundary methods (fences, hedges, walls) worldwide suggest that if a society truly needed a cost-effective, permanent barrier, they would not opt for a massive, discontinuous ditch with questionable defensive or boundary value. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

15. Toward a Deeper Understanding

Taken together, the modern LiDAR evidence, the glaring gaps, the odd alignments, and the juxtaposition with simpler global boundary practices demand a complete reassessment of Britain’s linear earthworks. Rather than dismiss them as straightforward Saxon lines or Roman leftover ditches, we should explore the possibility that they are part of a vast, prehistoric tapestry, repurposed or misconstrued by later cultures. Only by moving beyond the flawed “defense or boundary” paradigm can we hope to uncover their true origins and functions. Written by AI.

(Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

Introduction

Indeed, the modern term “dyke” or “dijk” can be traced back to its Dutch origins. As early as the 12th century, the construction of Dykes in the Netherlands was a well-established practice. One remarkable example of their ingenuity is the Westfriese Omringdijk, stretching an impressive 126 kilometres (78 miles), completed by 1250. This Dyke was formed by connecting existing older ‘dykes’, showcasing the Dutch mastery in managing their aquatic landscape. (Dykes Ditches and Earthworks)

The Roman chronicler Tacitus even provides an intriguing historical account of the Batavi, a rebellious people who employed a unique defence strategy during the year AD 70. They punctured the Dykes daringly, deliberately flooding their land to thwart their enemies and secure their retreat. This historical incident highlights the vital role Dykes played in the region’s warfare and water management.

Originally, the word “dijk” encompassed both the trench and the bank, signifying a comprehensive understanding of the Dyke’s dual nature – as both a protective barrier and a channel for water control. This multifaceted concept reflects the profound connection between the Dutch people and their battle against the ever-shifting waters that sought to reclaim their land.

The term “dyke” evolved as time passed, and its usage spread beyond the Dutch borders. Today, it represents not only a symbol of the Netherlands’ engineering prowess but also a universal symbol of human determination in the face of the relentless forces of nature. The legacy of these ancient Dykes lives on, a testament to the resilience and innovation of those who shaped the landscape to withstand the unyielding currents of time.

Upon studying archaeology, whether at university or examining detailed ordinance survey maps, one cannot help but encounter peculiar earthworks scattered across the British hillsides. Astonishingly, these enigmatic features often lack a rational explanation for their presence and purpose. Strangely enough, these features are frequently disregarded in academic circles, brushed aside, or provided with flimsy excuses for their existence. The truth is, these earthworks defy comprehension unless we consider overlooked factors at play.

One curious observation revolves around the term “Dyke,” inherently linked to water. It seems rather peculiar to apply such a word to an earthwork atop a hill unless an ancestral history has imparted its actual function through the ages. Let us consider the celebrated “Offa’s Dyke,” renowned for its massive linear structure, meandering along some of the present boundaries between England and Wales. This impressive feat stands as a testament to the past, seemingly demarcating the realms of the Anglian kingdom of Mercia and the Welsh kingdom of Powys during the 8th century.

However, delving further into the evidence and historical accounts challenges this seemingly straightforward explanation. Roman historian Eutropius, in his work “Historiae Romanae Breviarium”, penned around 369 AD, mentions a grand undertaking by Septimius Severus, the Roman Emperor, from 193 AD to 211 AD. In his pursuit of fortifying the conquered British provinces, Severus constructed a formidable wall stretching 133 miles from coast to coast.

Yet, intriguingly, none of the known Roman defences match this precise length. Hadrian’s Wall, renowned for its defensive prowess, spans a mere 70 miles. Could Eutropius have referred to Offa’s Dyke, which bears remarkable similarity to the Roman practice of initially erecting banks and ditches for defence?

| Figure 1- Offa’s Dyke (Red) – note that it is only complete if you connect the existing rivers to the ditches – (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke) |

The enigma persists, leaving us to ponder whether Offa’s Dyke, with its impressive extent, holds an ancient Roman legacy or represents a separate and awe-inspiring creation. As we navigate the depths of history, it becomes increasingly apparent that these earthworks hold hidden stories waiting to be revealed, revealing the multifaceted montage of Britain’s past and the extraordinary engineering feats that have shaped its landscape through the ages.

Indeed, history is a complex tapestry woven with a multitude of threads, and the interpretation of archaeological evidence often shapes our understanding of the past. Throughout history, conquerors and civilisations have repurposed existing features, such as ditches, augmenting them with defensive banks and walls to suit their strategic needs. The Romans and the Normans, among others, have demonstrated this practice.

In the case of Offa’s Dyke, the enigma deepens if we consider the possibility that the Romans were the architects behind its creation. Such a scenario challenges the conventional attribution of the Dyke to King Offa and raises questions about the true origins and purpose of this massive linear earthwork. Archaeological realities, or perhaps misinterpretations, can indeed hold the key to unveiling hidden facets of our history.

It is essential to approach historical accounts and archaeological evidence with a critical eye and an openness to multiple interpretations. The past often leaves tantalising clues that may require careful examination and reevaluation. By embracing the complexities and uncertainties of history, we can better appreciate the intricacies of human civilisation and the varied influences that have shaped it over the ages.

In pursuing truth, historians and archaeologists must remain receptive to new insights, allowing the evidence to guide their conclusions, even if it means challenging established narratives. By unravelling these historical puzzles, we can better understand our collective heritage, appreciating the rich combination of human experiences and the myriad forces that have moulded history. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

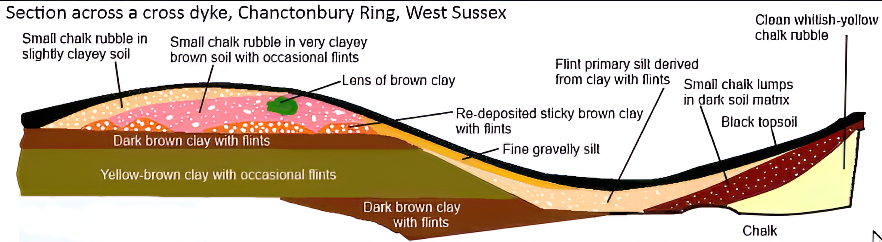

Cross-Dykes

The peculiar earthworks etched upon the British landscape have not eluded the discerning eyes of archaeologists and cartographers alike. These enigmatic features, often defying conventional explanations, have intrigued the curious minds of scholars and historians. A new designation, “Cross-Dykes,” has partially acknowledged their distinctiveness and unusual placement.

Cross-Dykes, substantial linear earthworks, grace the upland terrain, their lengths varying between 0.2km and 1km. Besides one or more banks, they bear ditches, running parallel in an enigmatic dance upon ridges and spurs. Historical excavations and analogies with related monuments paint a broader picture, extending back to the millennia of the Middle Bronze Age. Their purpose, though elusive, leans towards territorial boundaries, delineating parcels of land within ancient communities. But beyond such boundaries, they may have served as tracks or routes for cattle or even as defensive structures.

A pivotal element to grasp lies in the acknowledgement that Cross-Dykes have, at their core, a prehistoric origin. No longer shackled to erroneous notions of Saxon or medieval connections, these ancient features warrant a fresh lens to illuminate their true significance. The names of notable earthworks, like Wansdyke and Offa’s Dyke, may well bear a more profound revision in light of this newfound understanding.

Yet, we must not overlook the Historic England claim that only “very few” of these earthworks remain. The broader landscape contradicts this assertion, teeming with over 1500 scheduled ‘Linear Earthworks,’ showcasing the scope and magnitude of these intriguing remnants. Moreover, advancements in the art of surveying, as heralded by LiDAR, have revealed hidden troves of earthworks, once lost to the unyielding grasp of time and misinterpretation.

To critique archaeological theories with acuity, one must first comprehend their tenets. The evolving narrative seeks to unravel the enigma shrouding these linear earthworks, breathing life into ancient histories etched in the soil. Embracing a spirit of inquiry and remaining receptive to novel discoveries, we embark on a quest of unravelling the untold stories lingering within the terrain. With each revelation, the layers of history peel back, revealing a canvas of human ingenuity, perseverance, and the grandeur of the past, etched forever in the folds of Britain’s landscape. Archaeologists have (partially) recognised that these many earthworks are placed in strange areas for conventional explanations. Consequently, they have attempted to split a section away from the global term earthworks and called them ‘Cross-Dykes’. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

Boundary Markers

With their reliance on earthworks as territorial markers, the historical hypothesis surrounding land boundaries emerges as a thought-provoking inquiry. Yet, as we delve deeper into the evidence, a poignant need for more compelling proof becomes evident. Throughout history, societies have indeed relied on markers to delineate their domains, be they natural features like rivers or human-made constructs like hedgerows. The practicality and economy of such choices are undeniable, especially when contrasted with the labour-intensive and costly endeavour of constructing extensive ditches and banks.

In the case of the renowned Offa’s Dyke, a perplexing puzzle emerges. The border, at times, gracefully follows the course of a river, a logical and sensible demarcation. However, the sudden shift to an earthwork set behind the same river defies easy explanation. Such inconsistency leaves us questioning the premise of these earthworks as unequivocal markers. The presence of inexplicable gaps in the land border only deepens the enigma, raising further doubt about the validity of the hypothesis.

We must seek coherence and reason within any historical proposition. The current hypothesis falls short in offering a convincing rationale for this transition from river to earthwork, and it fails to address the glaring accessibility of the river as a natural and readily available boundary marker. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

| Figure 2 – Path of Offa’s Dyke – showing its not remotely straight |

As we navigate the terrain of ancient earthworks, a commitment to rigorous scrutiny is paramount. Only by subjecting our hypotheses to relentless examination can we hope to uncover the authentic truths that lie obscured beneath the layers of time. In embracing a spirit of inquiry and humility, we may yet unlock the profound secrets of these age-old earthworks, shedding light on the intricate relationships between humanity and the landscapes they once inhabited. The pursuit of understanding is a journey marked by discovery and wonder, and in this voyage, we honour the legacy of those who once shaped the contours of history upon British soil. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

Defensive Features

According to the pronouncements of esteemed Historical England, discerning the precise function of ancient boundaries proves to be an intricate endeavour. Whether they were intended for defence, stock-herding, or carrying symbolic significance remains elusive. In truth, most boundaries likely fulfilled a mosaic of roles, their purpose evolving and adapting over time. To presume that significant boundaries were solely for defence and smaller ones merely for livestock control would be an oversimplification of the intricate tapestry of history.

These artificial boundaries’ form, extent, and very existence offer vital clues, providing glimpses into their intended purposes. Additionally, their construction’s social and political context can provide insightful context. Yet, as we probe deeper into the historical narrative, it is evident that the written accounts primarily speak of Roman and Norman defence systems. With their ingenuity, the Romans devised the “ankle breaker” ditch – a V-shaped trench with a heightened counterscape masterfully designed to ensnare attackers or thwart mounted assailants.

These ingenious Roman ditches, predominantly surface near Roman sites, are conspicuously absent from 90% of excavations across Linear Earthworks. This absence challenges the prevailing hypothesis and prompts a reevaluation of past assumptions. In particular, investigations into Dykes such as Offa’s have uncovered an unsettling revelation – the defensive banks, in over 10% of the alignment, face the “wrong way.” This finding raises questions about the potential bias that may have influenced the support for this theory in the past.

As the archaeological landscape evolves, a shift is subtly underway, with many archaeologists quietly distancing themselves from this 20th-century hypothesis. The quest for truth demands unyielding inquiry, and as more mysteries come to light, the intricacies of ancient earthworks unfurl before our eyes. In the spirit of intellectual progress, we must approach each enigma with an open mind, ever eager to grasp the trutyh over mythology. (Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

(Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

2025 Update

Historic England Confirms the Prehistoric Origins of Britain’s Linear Earthworks

Why Offa’s and Wansdyke Are Not Saxon Ditches

By The Prehistoric AI Team

For over a century, archaeologists have confidently told the public that Britain’s great linear earthworks—Offa’s Dyke, Wansdyke, and their lesser-known cousins—were “Saxon defensive boundaries.” Yet even the government’s own heritage body now quietly admits otherwise.

In its official publication HEAG 219: Prehistoric Linear Boundary Earthworks (Historic England, 2018), the evidence is laid out in black and white: these monumental ditches and banks are not the product of medieval kingdoms but of prehistoric engineering, reaching back thousands of years before Offa or Rome.

1. Historic England’s Own Words

“From the Neolithic period onwards in the British Isles, natural boundaries such as watercourses and escarpments have been supplemented by artificial boundaries, often formed by a ditch and bank.”

(HEAG 219, p.2)

That sentence alone demolishes the Saxon myth. These “artificial boundaries” appear from around 3600 BCE, the same period as Britain’s causewayed enclosures and early field systems.

“The earliest conventional linear earthwork so far confirmed, dating to around 3600 BC, follows the crest of the western escarpment of Hambleton Hill, Dorset, for perhaps as much as 3 km.”

(HEAG 219, p.7)

In other words, the engineering tradition behind Offa’s and Wansdyke was already flourishing five thousand years earlier than the supposed Saxon period.

2. Confusion by Reuse

“Some of these early boundaries… continued to structure the social and economic landscape through the Iron Age and into the Roman period. Indeed, some have seen continuous use, or repeated re-use, from prehistory to the present day.”

(HEAG 219, p.7)

This statement is key.

What later archaeologists labelled as “Roman” or “Saxon” were often prehistoric earthworks re-used by later peoples. Defensive adaptations may have been made, but the physical structures already existed—centuries or millennia earlier.

Langdon’s LiDAR analysis of Wansdyke and Offa’s Dyke shows this perfectly: continuous, water-connected segments, truncated by rivers and palaeochannels, betray origins in a hydrological engineering system, not a medieval frontier.

3. Historic England Admits Mis-Dating Risks

“Prehistoric examples can be confused with medieval or later ones… Their form is not often diagnostic.”

(HEAG 219, p.7)

This rare confession from within Historic England supports Langdon’s long-standing criticism of archaeological dating methods. When earthworks lack carbonised deposits, dating often depends on surface finds—antler picks, pottery sherds, or even stray Roman coins—leading to circular logic.

As Prehistoric Dykes (Canals) argued, this flawed reasoning has turned prehistoric infrastructure into “Saxon defences” by default.

4. Functional Variety, Not Fortification

“It is often difficult to determine whether a particular boundary was used for defence, for stock-herding, or purely as a symbol; in truth, most boundaries probably served all of these functions to varying degrees.”

(HEAG 219, p.2)

The report concedes that no single explanation fits. The traditional defensive model collapses under scrutiny: there are no battle remains, no arrowheads, and no consistent rampart orientations.

This aligns with Langdon’s hydrological interpretation—seeing these earthworks as water management and navigation canals formed when Britain’s post-glacial landscape still retained a higher water table. Their engineering precision makes sense when viewed as prehistoric canalisation, not Saxon militarism.

5. The Official Timeline

Historic England’s own chart places linear boundaries firmly in the Neolithic and Bronze Age, with only reuse continuing into later eras:

Linear Boundaries Timeline (HEAG 219, p.

4000 BC – Neolithic beginnings

1500 BC – Bronze Age expansion

0 AD – Roman reuse

The Saxon period doesn’t even feature.

6. What This Means

The implications are profound. Historic England has, perhaps unintentionally, validated the central premise of the Prehistoric Dyke Hypothesis:

Britain’s linear earthworks are prehistoric hydraulic and boundary systems, later adopted but not created by historical kingdoms.

The narrative of “Saxon kings digging 100-mile ditches by hand” finally collapses under the weight of its own impossibility—and the evidence from both LiDAR and the nation’s own heritage authority.

7. A New Understanding

The HEAG 219 publication is cautious in tone, but its data speaks volumes. The earliest linear boundaries coincide with the rise of complex water management systems, just as Langdon’s LiDAR work shows canal-like forms and river terminations.

It is time to update the textbooks:

Wansdyke, Offa’s Dyke, Car Dyke and their lesser cousins are prehistoric canals—part of a sophisticated hydrological network that once crisscrossed a flooded Britain.

Conclusion

Even Historic England now concedes that Britain’s linear earthworks belong to prehistory, not the Dark Ages.

By accepting this evidence, we move beyond folklore and into a genuinely scientific framework—one where landscape engineering, water management, and maritime trade define our ancestors’ genius.

Sources:

- Historic England (2018) Prehistoric Linear Boundary Earthworks: Introductions to Heritage Assets (HEAG 219).

- Langdon, R.J. (2022) Prehistoric Dykes (Canals) – Wansdyke v1.2.

- Langdon, R.J. (2024) Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth.

Exploring Prehistoric Britain: A Journey Through Time

My blog delves into the fascinating mysteries of prehistoric Britain, challenging conventional narratives and offering fresh perspectives based on cutting-edge research, particularly using LiDAR technology. I invite you to explore some key areas of my research. For example, the Wansdyke, often cited as a defensive structure, is re-examined in light of new evidence. I’ve presented my findings in my blog post Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’, and a Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover video further visualizes my conclusions.

My work also often challenges established archaeological dogma. I argue that many sites, such as Hambledon Hill, commonly identified as Iron Age hillforts are not what they seem. My posts Lidar Investigation Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’ and Unmasking the “Iron Age Hillfort” Myth explore these ideas in detail and offer an alternative view. Similarly, sites like Cissbury Ring and White Sheet Camp, also receive a re-evaluation based on LiDAR analysis in my posts Lidar Investigation Cissbury Ring through time and Lidar Investigation White Sheet Camp, revealing fascinating insights into their true purpose. I have also examined South Cadbury Castle, often linked to the mythical Camelot56.

My research also extends to the topic of ancient water management, including the role of canals and other linear earthworks. I have discussed the true origins of Car Dyke in multiple posts including Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast and Lidar Investigation Car Dyke – North Section, suggesting a Mesolithic origin2357. I also explore the misidentification of Roman aqueducts, as seen in my posts on the Great Chesters (Roman) Aqueduct. My research has also been greatly informed by my post-glacial flooding hypothesis which has helped to inform the landscape transformations over time. I have discussed this hypothesis in several posts including AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis and Exploring Britain’s Flooded Past: A Personal Journey

Finally, my blog also investigates prehistoric burial practices, as seen in Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain and explores the mystery of Pillow Mounds, often mistaken for medieval rabbit warrens, but with a potential link to Bronze Age cremation in my posts: Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation? and The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?. My research also includes the astronomical insights of ancient sites, for example, in Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival. I also review new information about the construction of Stonehenge in The Stonehenge Enigma.

(Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

Further Reading

For those interested in British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk, a comprehensive resource featuring an extensive collection of archaeology articles, modern LiDAR investigations, and groundbreaking research. The site also includes insights and extracts from the acclaimed Robert John Langdon Trilogy, a series of books exploring Britain during the Prehistoric period. Titles in the trilogy include The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and The Post Glacial Flooding Hypothesis, offering compelling evidence about ancient landscapes shaped by post-glacial flooding.

To further explore these topics, Robert John Langdon has developed a dedicated YouTube channel featuring over 100 video documentaries and investigations that complement the trilogy. Notable discoveries and studies showcased on the channel include 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History and the revelation of Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue, a rediscovered prehistoric feature at Avebury, Wiltshire.

In addition to his main works, Langdon has released a series of shorter, accessible publications, ideal for readers delving into specific topics. These include:

- The Ancient Mariners

- Stonehenge Built 8300 BCE

- Old Sarum

- Prehistoric Rivers

- Dykes, Ditches, and Earthworks

- Echoes of Atlantis

- Homo Superior

- 13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History

- Silbury Avenue – The Lost Stone Avenue

- Offa’s Dyke

- The Stonehenge Enigma

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- The Stonehenge Hoax

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation

- Darwin’s Children

- Great Chester’s Roman Aqueduct

- Wansdyke

For active discussions and updates on the trilogy’s findings and recent LiDAR investigations, join our vibrant community on Facebook. Engage with like-minded enthusiasts by leaving a message or contributing to debates in our Facebook Group.

Whether through the books, the website, or interactive videos, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of Britain’s fascinating prehistoric past. We encourage you to explore these resources and uncover the mysteries of ancient landscapes through the lens of modern archaeology.

For more information, including chapter extracts and related publications, visit the Robert John Langdon Author Page. Dive into works such as The Stonehenge Enigma or Dawn of the Lost Civilisation, and explore cutting-edge theories that challenge traditional historical narratives.

(Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

(Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke)