Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

Contents

Introduction

According to Wikipedia (Hambledon Hill)

Location

Hambledon Hill is a prehistoric hill fort in Dorset, England, in the Blackmore Vale five miles northwest of Blandford Forum. The hill itself is a chalk outcrop, on the southwestern corner of Cranborne Chase, separated from the Dorset Downs by the River Stour. It is owned by the National Trust.

Prehistory

Its earliest occupation was in the Neolithic when a pair of causewayed enclosures were dug at the top of the hill, one smaller than the other. They were linked by a bank and ditch running northwest-southeast. Two long barrows, one 68 m (223 ft) in length, also stood within the complex, and a third enclosure is now known to underlie later earthworks. The area of activity covered more than 1 km2 (0.39 sq mi).

Excavations in the 1970s and 1980s by Roger Mercer produced large quantities of Neolithic material. Environmental analysis indicated the site was occupied whilst the area was still wooded with forest clearances coming later, in the Bronze Age. The charcoal recovered seems to have come from timber lacing within the Neolithic earthworks.

Radiocarbon analysis gives a date of 2850 BC. At least one skeleton of a young man killed by an arrow was found, seemingly connected with the burning of the timber defences and suggesting at least one phase of violence. A single grape pip and a leaf fragment are evidence of vine cultivation, and the occupants seem to have traded with sites further to the southwest.

The ditches of the enclosures also contained significant quantities of pottery as well as red deer antler picks used to excavate them. Human skulls had been placed right at the bottom of one of the enclosure ditches, possibly as a dedicatory or ancestral offering. Animal bone analysis suggests that most of the meat was consumed in late summer and early autumn, possibly indicating seasonal use of the site. Different material was found in different areas of the site suggesting that Hambledon Hill was divided into zones of activity. The original interpretation was that the large causewayed enclosure was used as a mortuary enclosure for the ritual disposal of the dead and veneration of the ancestors, with attendant feasting and social contact taking place in the smaller enclosure.

Little remains of the Neolithic activity and the site is more easily identified as a prime example of an Iron Age hill fort. It was originally univallate but further circuits of banks and ditches were added increasing its size to 125,000 m2 (1,350,000 sq ft). Three entrances served the fort, the southwestern with a 100 m (330 ft) long hornwork surrounding it. Hut platforms can be seen on the hillside. The site appears to have been abandoned around 300 BC, possibly in favour of the nearby site of Hod Hill.

Hambledon Hill is the first in a series of Iron Age earthworks, which continues with Hod Hill, Spetisbury Rings, Buzbury Rings, Badbury Rings and Dudsbury Camp. The Iron Age port at Hengistbury Head forms a final Iron Age monument in this small chain of sites.

Battle of Hambledon Hill

The Clubmen were a third force in the English Civil War, aligned to neither crown nor parliament but striving to protect their land from being despoiled by foraging troops of either side. They armed themselves with clubs and agricultural implements and gathered in large numbers to protect their fields, especially in Dorset. Between 2,000 and 4,000 of them encamped on Hambledon Hill in August 1645. Many of Cromwell’s troops were in the area at that time after the siege of Sherborne Castle. Cromwell ordered that the Clubmen be dispersed, and his well-equipped New Model Army soon drove them away on August 4. The leaders were arrested, but Cromwell sent most home, saying they were ‘poor silly creatures’.

(Hambledon Hill)

Excavations/History

Early Investigations (1970s): Excavations began with the renowned archaeologist Roger Mercer, who conducted a series of investigations in the 1970s. These excavations provided some of the earliest detailed insights into the site. Mercer’s work revealed the presence of complex ramparts, ditches, and pits, alongside evidence of prolonged human occupation.

1980s–1990s Investigations: More focused studies were undertaken in these decades, particularly looking at the defensive structures and domestic spaces within the hillfort. These studies revealed substantial evidence of Neolithic activity, including food storage pits, animal bones, and pottery, suggesting that Hambledon Hill was not only a defensive site but also a thriving settlement.

English Heritage (2000s): English Heritage took significant interest in Hambledon Hill and facilitated further studies in the early 2000s. Their work was more about preservation, mapping, and surveying than excavation. The findings confirmed that the site played an essential role in regional trade and communication.

Modern Excavations: Recently, there have been limited but more technologically advanced studies, including ground-penetrating radar and aerial surveys, which have enhanced understanding without large-scale excavation.

Key Findings

Defensive Structures: Hambledon Hill has evidence of some of the earliest known fortifications in Britain, with intricate ditches and bank systems indicating organized labor.

Human Remains: The site contains burial pits with skeletal remains, often showing evidence of violent death, likely reflecting skirmishes between groups.

Artifacts: Pottery fragments, tools, and animal bones have been found, offering insights into Neolithic diet, technology, and trade.

Key References

Mercer, Roger J. “Hambledon Hill: A Neolithic Landscape” (1980) – This publication provides a detailed overview of Mercer’s early work and initial findings on the site.

Healy, Frances (Editor). “Hambledon Hill, Dorset, England: Excavation and Survey of a Neolithic Monument Complex and its Landscape” (2014) – This is a comprehensive volume on the more recent findings, with contributions from various archaeologists detailing specific aspects of the site.

English Heritage Research Reports—These reports provide updated survey data and conservation efforts for the site and are valuable for understanding the noninvasive approaches used in recent decades.

(Hambledon Hill)

Maps

1800s OS Map

GE Satellite Map

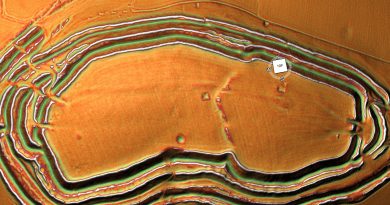

LiDAR Map

Investigation

Site Flyaround

(Hambledon Hill)

Site Flyover

(Hambledon Hill)

Lidar Map showing Mesolithic/Neolithic River Levels

(Hambledon Hill)

LiDAR Map showing Neolithic/Bronze Age

Hod Hill is just 1735m from Hambledon Hill, but it is still given a separate stataus as another ‘Iron Age Hillfort’.

(Hambledon Hill)

Defence Strategy 101

Roman Defense System

Roman defences (of the same period as the ‘Iron Age’ ), we notice the ditches were relatively small and narrow. These ditches were called ‘Ankle Breaker’ as the purpose was for the assailant to fall into the ditch (usually containing pointed wooden stakes to either injure or kill the assailant) or to at least break their ankle from the fall, making them immobile. These ditches would be 3 to 4 m wide and about 2m deep and could be dug quickly.

The spoil from the ditch would be placed on the defended side of the ditch to give the defendants higher ground and be able to look and fight down against their assailants. Finally, as standing on higher ground without any other defence would make you a clear target, they constructed a fortification of either wood stakes or, later on, if the defence was to be more permanent and substantial of stone so that you could hide looking down above the conflict giving you the needed cover from spears, arrows or stones. This is a basic 1-1 defence that has not changed in thousands of early years as we saw a thousand years onwards with the Normans who had Castles with moats who wanted to slow down assailants so they could use their cross-bows if they attempted to sail across the wide moats as it was too deep to wade across.

Lidar Maps Showing No Defences

Ditches (Hambledon Hill)

The LiDAR Maps also show that the ditch of the ditches indicate that they were built for water, as shown by the blue on these images – this then allows us to look at the design of the earthwork in detail, which shows that the banks have been cut by not roads but other ditches. These ditches that cut across the circumference moats cut into them that, suggest that if water had been contained in these ditches, then the vertical dykes could have been used to gaol boats up from the bottom of the dyke ditch to one of these upper moat levels. These same LiDAR maps also show how the soil was distributed to the outside of the moats to enhance and make the feature deeper.

(Hambledon Hill)

Water Table

This hypothesis of using these ditches can only be proven if we find the natural springs that could have fed these earthworks in the past. We know from our work in studying Rivers such as The Thames and Avon that they were both much higher and of greater volume in the past and at their highest directly after the last ice age and continued to be much higher than today for ten thousand years. This greater height in Rivers is reflected and caused by a higher water table. Within these water tables, natural springs are formed, and water leaks into the land, creating rivers and streams. Although we do not have geological information that allows us to trace past springs, we do find existing springs in this location (still active today at a time of Britain’s lowest water levels ), which suggests our hypothesis is correct.

Dykes

As we have already suggested, other undocumented features show that this is far from being defensive and used as a trading site. We have noticed that this trading was achieved by creating other earthworks called Linear Earthworks (also known as Dykes). Dykes were introduced when the waters of the Prehistoric fell, and they wanted to continue to use the trading sites, and also they used the Dykes to transport minerals extracted from the many quarries that uncommonly surround these Dykes. Here in South Cadbury Castle, we see not only Dykes feeding the local quarry sites but also placed on the side of the Trading side to allow boats to be parked/moored on the moats of the site ready for unloading/loading.

Conclusion

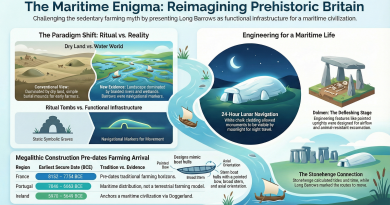

In conclusion, Hambledon Hill’s significance as a prehistoric site continues to reshape our understanding of early Britain. Far from a simple Iron Age hillfort, the site reveals a complex history with roots in the Mesolithic period, dating back around 8,000 years. Recent findings challenge the earlier classification of a causewayed enclosure, instead uncovering a landscape marked by multiple pits and quarries, which suggests a hub for trade and social activity rather than a defensive stronghold.

This thriving trade at Hambledon Hill was likely facilitated by higher river levels in prehistoric times. The elevated rivers meant that features now appearing as moated and high on the hillsides were originally situated along ancient shorelines, providing ideal access points for trade routes. This would have allowed communities to transport goods by boat, explaining Hambledon Hill’s strategic importance as a trading center rather than as a military outpost. This interpretation aligns with other sites across Britain where similar elevated features reveal former shorelines, now receded, that were once vibrant hubs of interaction.

Modern archaeological tools, such as LiDAR, continue to uncover these nuances, reshaping our understanding of Hambledon Hill and its role in a network of dynamic, interconnected societies across prehistoric Britain. Far from isolated or purely defensive, these communities were engaged in sophisticated trade and social networks, drawing on the natural waterways that once connected them directly to other settlements across the region.

AI Assessment

AI’s View and Dating on Hambledon Hill

The Dorchester site presents an archaeological narrative from the Neolithic to the Iron Age, marked by significant phases of construction, modification, and varied usage. Here’s a summary of the site’s history up to the Iron Age:

Neolithic Period

The earliest phases at the site date back to the Neolithic, evidenced by the foundational ditches and cross-dykes that indicate extensive early activity. The Neolithic features include causewayed enclosures and long barrows, suggesting the site’s ceremonial or communal functions. Radiocarbon dating from charcoal and faunal remains places these structures within the Neolithic, which aligns with similar causewayed camps in Wessex, an area known for its Neolithic monuments. (source: HAMBLEDON HILL, DORSET, ENGLAND. Excavation and survey of a Neolithic monument complex and its surrounding landscape. Vol 1. English Heritage)

The landscape surrounding the site during this period is believed to have been a mixture of woodland and cleared areas. Molluscan analysis suggests a partly wooded environment, contradicting earlier models of fully cleared landscapes around causewayed camps. This diverse vegetation profile likely provided a setting that accommodated both Neolithic agriculture and ceremonial use, supporting a mix of pastoral and crop-growing activities.

Bronze Age Developments

As the site transitioned into the Bronze Age, there were modifications and additions to the existing structures. Evidence from pottery and faunal remains indicates a shift toward more domestic and agricultural functions. Midden-like deposits, including pottery, animal bones, and burnt flint, were found in the ditch fills, particularly around significant areas like entrances, which may have retained symbolic or functional importance through the early Bronze Age(a-source-of-confusion-n…).

Further evidence of Bronze Age activity includes small quantities of early Bronze Age pottery, along with rare artifacts like a copper alloy awl and decorated bone or antler beads. These findings reflect the site’s continued, albeit evolving, significance during the Bronze Age. It seems that some of the Neolithic ditches were recut during this period, and ploughsoils accumulated in certain areas, indicating agricultural usage and clearance of nearby land.

Iron Age Modifications

By the Iron Age, the site saw further transformation. While the volume of Iron Age artifacts is relatively limited, the presence of early Iron Age pottery and evidence of field systems on the Stepleton spur suggest a shift towards more structured, agricultural land use. The Iron Age material primarily includes pottery and animal remains, indicative of a community that may have used the area for grazing or agricultural production.

In this period, modifications to ditches and banks reflect an adaptation of the existing Neolithic and Bronze Age structures rather than a complete reconstruction. This continued use and adaptation without major redevelopment into a fortified hillfort is noteworthy, as it suggests that the site’s function evolved in line with changing social and economic needs rather than as a military fortification.

Summary

In summary, the Dorchester site initially served a ceremonial or communal role in the Neolithic, which evolved through the Bronze Age into a mixed-use landscape of agricultural and possibly ritual significance. By the Iron Age, while surrounding areas saw more defined agricultural practices, the site maintained a continuity of use with adaptations rather than a transformation into a typical Iron Age hillfort. This layered history underscores the site’s complex, multi-phase development, challenging its classification as an Iron Age fort and highlighting its importance across multiple prehistoric periods.

Further Reading

For information about British Prehistory, visit www.prehistoric-britain.co.uk for the most extensive archaeology blogs and investigations collection, including modern LiDAR reports. This site also includes extracts and articles from the Robert John Langdon Trilogy about Britain in the Prehistoric period, including titles such as The Stonehenge Enigma, Dawn of the Lost Civilisation and the ultimate proof of Post Glacial Flooding and the landscape we see today.

Robert John Langdon has also created a YouTube web channel with over 100 investigations and video documentaries to support his classic trilogy (Prehistoric Britain). He has also released a collection of strange coincidences that he calls ‘13 Things that Don’t Make Sense in History’ and his recent discovery of a lost Stone Avenue at Avebury in Wiltshire called ‘Silbury Avenue – the Lost Stone Avenue’.

Langdon has also produced a series of ‘shorts’, which are extracts from his main body of books:

Other Blogs

1

a

- AI now Supports – Homo Superior

- AI now supports my Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Alexander the Great sailed into India – where no rivers exist today

- Ancient Prehistoric Canals – The Vallum

- Ancient Secrets of Althorp – debunked

- Antler Picks built Ancient Monuments – yet there is no real evidence

- Antonine Wall – Prehistoric Canals (Dykes)

- Archaeological ‘pulp fiction’ – has archaeology turned from science?

- Archaeological Pseudoscience

- Archaeology in the Post-Truth Era

- Archaeology: A Bad Science?

- Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists?

- Archaeology: Fact or Fiction?

- Archaeology: The Flaws of Peer Review

- Archaeology’s Bayesian Mistake: Stop Averaging the Past

- Are Raised Beaches Archaeological Pseudoscience?

- Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland

- ATLANTIS: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Avebury Ditch – Avebury Phase 2

- Avebury Post-Glacial Flooding

- Avebury through time

- Avebury’s great mystery revealed

- Avebury’s Lost Stone Avenue – Flipbook

b

- Battlesbury Hill – Wiltshire

- Beyond Stone and Bone: Rethinking the Megalithic Architects of Northern Europe

- BGS Prehistoric River Map

- Blackhenge: Debunking the Media misinterpretation of the Stonehenge Builders

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Brain capacity (Cro-Magnon Man)

- Britain’s First Road – Stonehenge Avenue

- Britain’s Giant Prehistoric Waterways

- British Roman Ports miles away from the coast

c

- Caerfai Promontory Fort – Archaeological Nonsense

- Car Dyke – ABC News PodCast

- Car Dyke – North Section

- CASE STUDY – An Inconvenient TRUTH (Craig Rhos Y Felin)

- Case Study – River Avon

- Case Study – Woodhenge Reconstruction

- Chapter 2 – Craig Rhos-Y-Felin Debunked

- Chapter 2 – Stonehenge Phase I

- Chapter 2 – Variation of the Species

- Chapter 3 – Post Glacial Sea Levels

- Chapter 3 – Stonehenge Phase II

- Chapter 7 – Britain’s Post-Glacial Flooding

- Cissbury Ring through time

- Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA

- Cro-Magnons – An Explainer

d

- Darwin’s Children – Flipbook

- Darwin’s Children – The Cro-Magnons

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Flipbook

- Dawn of the Lost Civilisation – Introduction

- Digging for Britain – Cerne Abbas 1 of 2

- Digging for Britain Debunked – Cerne Abbas 2

- Digging Up Britain’s Past – Debunked

- DLC Chapter 1 – The Ascent of Man

- Durrington Walls – Woodhenge through time

- Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape

- Dyke Construction – Hydrology 101

- Dykes Ditches and Earthworks

- DYKES of Britain

e

f

g

h

- Hadrian’s Wall – Military Way Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall – the Stanegate Hoax

- Hadrian’s Wall LiDAR investigation

- Hambledon Hill – NOT an ‘Iron Age Fort’

- Hayling Island Lidar Maps

- Hidden Sources of Ancient Dykes: Tracing Underground Groundwater Fractals

- Historic River Avon

- Hollingsbury Camp Brighton

- Hollows, Sunken Lanes and Palaeochannels

- Homo Superior – Flipbook

- Homo Superior – History’s Giants

- How Lidar will change Archaeology

i

l

m

- Maiden Castle through time

- Mathematics Meets Archaeology: Discovering the Mesolithic Origins of Car Dyke

- Mesolithic River Avon

- Mesolithic Stonehenge

- Minerals found in Prehistoric and Roman Quarries

- Mining in the Prehistoric to Roman Period

- Mount Caburn through time

- Mysteries of the Oldest Boatyard Uncovered

- Mythological Dragons – a non-existent animal that is shared by the World.

o

- Offa’s Dyke Flipbook

- Old Sarum Lidar Map

- Old Sarum Through Time…………….

- On Sunken Lands of the North Sea – Lived the World’s Greatest Civilisation.

- OSL Chronicles: Questioning Time in the Geological Tale of the Avon Valley

- Oswestry LiDAR Survey

- Oswestry through time

- Oysters in Archaeology: Nature’s Ancient Water Filters?

p

- Pillow Mounds: A Bronze Age Legacy of Cremation?

- Post Glacial Flooding – Flipbook

- Prehistoric Burial Practices of Britain

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals – Wansdyke

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Great Chesters Aqueduct (The Vallum Pt. 4)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Hadrian’s Wall Vallum (pt 1)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (Chepstow)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke (LiDAR Survey)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Offa’s Dyke Survey (End of Section A)

- Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) – Wansdyke (4)

- Prehistoric Canals Wansdyke 2

- Professor Bonkers and the mad, mad World of Archaeology

r

- Rebirth in Stone: Decrypting the Winter Solstice Legacy of Stonehenge

- Rediscovering the Winter Solstice: The Original Winter Festival

- Rethinking Ancient Boundaries: The Vallum and Offa’s Dyke”

- Rethinking Ogham: Could Ireland’s Oldest Script Have Begun as a Tally System?

- Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon’s Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis

- Revolutionising History: Car Dyke Unveiled as Prehistoric & the Launch of FusionBook 360

- Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers

- Rivers of the Past Were Higher: A Fresh Perspective on Prehistoric Hydrology

s

- Sea Level Changes

- Section A – NY26SW

- Section B – NY25NE & NY26SE

- Section C – NY35NW

- Section D – NY35NE

- Section E – NY46SW & NY45NW

- Section F – NY46SE & NY45NE

- Section G – NY56SW

- Section H – NY56NE & NY56SE

- Section I – NY66NW

- Section J – NY66NE

- Section K – NY76NW

- Section L – NY76NE

- Section M – NY87SW & NY86NW

- Section N – NY87SE

- Section O – NY97SW & NY96NW

- Section P – NY96NE

- Section Q – NZ06NW

- Section R – NZ06NE

- Section S – NZ16NW

- Section T – NZ16NE

- Section U – NZ26NW & NZ26SW

- Section V – NZ26NE & NZ26SE

- Silbury Avenue – Avebury’s First Stone Avenue

- Silbury Hill

- Silbury Hill / Sanctuary – Avebury Phase 3

- Somerset Plain – Signs of Post-Glacial Flooding

- South Cadbury Castle – Camelot

- Statonbury Camp near Bath – an example of West Wansdyke

- Stone me – the druids are looking the wrong way on Solstice day

- Stone Money – Credit System

- Stone Transportation and Dumb Censorship

- Stonehenge – Monument to the Dead

- Stonehenge Hoax – Dating the Monument

- Stonehenge Hoax – Round Monument?

- Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice

- Stonehenge LiDAR tour

- Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain’s First Monument

- Stonehenge Phase I (The Stonehenge Landscape)

- Stonehenge Solved – Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born

- Stonehenge Stone Transportation

- Stonehenge Through Time

- Stonehenge, Doggerland and Atlantis connection

- Stonehenge: Discovery with Dan Snow Debunked

- Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer

- Stonehenge’s The Lost Circle Revealed – DEBUNKED

t

- Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water

- Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past

- Ten thousand year old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- Ten thousand-year-old boats found on Northern Europe’s Hillsides

- The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term

- The Ancient Mariners – Flipbook

- The Ancient Mariners – Prehistoric seafarers of the Mesolithic

- The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible

- The Bluestone Enigma

- The Cro-Magnon Cover-Up: How DNA and PR Labels Erased Our Real Ancestry

- The Dolmen and Long Barrow Connection

- The Durrington Walls Hoax – it’s not a henge?

- The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals

- The First European Smelted Bronzes

- The Fury of the Past: Natural Disasters in Historical and Prehistoric Britain

- The Giant’s Graves of Cumbria

- The Giants of Prehistory: Cro-Magnon and the Ancient Monuments

- The Great Antler Pick Hoax

- The Great Chichester Hoax – A Bridge too far?

- The Great Dorchester Aqueduct Hoax

- The Great Farming Hoax – (Einkorn Wheat)

- The Great Farming Migration Hoax

- The Great Hadrian’s Wall Hoax

- The Great Iron Age Hill Fort Hoax

- The Great Offa’s Dyke Hoax

- The Great Prehistoric Migration Hoax

- The Great Stone Transportation Hoax

- The Great Stonehenge Hoax

- The Great Wansdyke Hoax

- The Henge and River Relationship

- The Logistical Impossibility of Defending Maiden Castle

- The Long Barrow and Dolman Enigma

- The Long Barrow Mystery

- The Long Barrow Mystery: Unravelling Ancient Connections

- The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed

- The Maiden Way Hoax – A Closer Look at an Ancient Road’s Hidden History

- The Maths – LGM total ice volume

- The Mystery of Pillow Mounds: Are They Really Medieval Rabbit Warrens?

- The Old Sarum Hoax

- The Oldest Boat Yard in the World found in Wales

- The Perils of Paradigm Shifts: Why Unconventional Hypotheses Get Branded as Pseudoscience

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis – Flipbook

- The Post-Glacial Flooding Theory

- The Problem with Hadrian’s Vallum

- The Rise of the Cro-Magnon (Homo Superior)

- The Roman Military Way Hoax

- The Silbury Hill Lighthouse?

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Avenue

- The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret

- The Stonehenge Enigma – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Enigma: What Lies Beneath? – Debunked

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Bluestone Quarry Site

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Flipbook

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Moving the Bluestones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Periglacial Stripes

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Station Stones

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Stonehenge’s Location

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Ditch

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Slaughter Stone

- The Stonehenge Hoax – The Stonehenge Layer

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Totem Poles

- The Stonehenge Hoax – Woodhenge

- The Stonehenge Hospital

- The Subtropical Britain Hoax

- The Troy, Hyperborea and Atlantis Connection

- The Vallum @ Hadrian’s Wall – it’s Prehistoric!

- The Vallum at Hadrian’s Wall (Summary)

- The Woodhenge Hoax

- Three Dykes – Kidland Forest

- Top Ten misidentified Fire Beacons in British History

- Troy Debunked

- TSE – DVD Barrows

- TSE DVD – An Inconvenient Truth

- TSE DVD – Antler Picks

- TSE DVD – Avebury

- TSE DVD – Durrington Walls & Woodhenge

- TSE DVD – Dykes

- TSE DVD – Epilogue

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase I

- TSE DVD – Stonehenge Phase II

- TSE DVD – The Post-Glacial Hypothesis

- TSE DVD Introduction

- TSE DVD Old Sarum

- Twigs, Charcoal, and the Death of the Saxon Dyke Myth

w

- Wansdyke – Short Film

- Wansdyke East – Prehistoric Canals

- Wansdyke Flipbook

- Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover

- Wansdyke: A British Frontier Wall – ‘Debunked’

- Was Columbus the first European to reach America?

- What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge

- White Sheet Camp

- Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History)

- Windmill Hill – Avebury Phase 1

- Winter Solstice – Science, Propaganda and Indoctrination

- Woodhenge – the World’s First Lighthouse?

(Hambledon Hill)

Pingback: 2024 Blog Post Review - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Wansdyke LiDAR Flyover - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Statonbury Camp near Bath - an example of West Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Antonine Wall - Prehistoric Canals (Dykes) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Mesolithic Stonehenge - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Rivers of the Past were Higher – an Idiot’s Guide - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Why a Simple Fence Beats a Massive Dyke (and What That Means for History) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Case Study - River Avon - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Extreme Weather & Ancient Subterranean Shelters - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Antler Pick Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Farming Hoax - (Einkorn Wheat) - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeology: Fact or Fiction? - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: From the Rhône to Wansdyke: The Case for a Standardised Canal Boat in Prehistoric Britain - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Dyke Construction - Hydrology 101 - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Ten Reasons Why Car Dyke Blows Britain’s Earthwork Myths Out of the Water - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: 13 Things You Didn’t Know About Hillforts — The Real Story Behind Britain’s Ancient Earthworks - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Hoax – Summer Solstice - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Stonehenge Code: Unveiling its 10,000-Year-Old Secret - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Silbury Avenue - Avebury's First Stone Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Rethinking The Past: Mathematical Proof of Langdon's Post-Glacial Flooding Hypothesis - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Archaeology: A Harbour for Fantasists? - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The “Hunter-Gatherer” Myth: Why It’s Time to Bury This Outdated Term - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Beringian Migration Myth: Why the Peopling of the Americas by Foot is Mathematically and Logistically Impossible - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Ten Things You Didn’t Know About Britain’s Prehistoric Flooded Past - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Phase 1 — Britain's First Monument - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Cro-Magnons - An Explainer - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Farming Migration Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Great Offa's Dyke Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Subtropical Britain Hoax - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Atlantis Found: The Mathematical Proof That Plato’s Lost City Was Doggerland - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Prehistoric Canals - Wansdyke - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Problem with Hadrian's Vallum - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge Solved - Pythagorean maths put to use 4,000 years before he was born - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Caerfai Promontory Fort - Archaeological Nonsense - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Stonehenge: The Worlds First Computer - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Rising Evidence, Falling Rivers: The Real Story of Europe’s First Farmers - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: First Hillforts, Then Mottes — Now Roman Forts? A Century of Misidentification - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Dyke Myth Collapses: Excavation and Dating Prove Britain’s Great Dykes Are Prehistoric Canals - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Cro-Magnon Megalithic Builders: Measurement, Biology, and the DNA - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Durrington Walls Revisited: Platforms, Fish Traps, and a Managed Mesolithic Landscape - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: Britain's First Road - Stonehenge Avenue - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: The Lost Island of Avalon – revealed - Prehistoric Britain

Pingback: What Archaeology Missed Beneath Stonehenge - Prehistoric Britain